Abstract

Breast cancer is one of the most aggressive types of cancer, and its early diagnosis is crucial for reducing mortality rates and ensuring timely treatment. Computer-aided diagnosis systems provide automated mammography image processing, interpretation, and grading. However, since the currently existing methods suffer from such issues as overfitting, lack of adaptability, and dependence on massive annotated datasets, the present work introduces a hybrid approach to enhance breast cancer classification accuracy. The proposed Q-BGWO-SQSVM approach utilizes an improved quantum-inspired binary Grey Wolf Optimizer and combines it with SqueezeNet and Support Vector Machines to exhibit sophisticated performance. SqueezeNet’s fire modules and complex bypass mechanisms extract distinct features from mammography images. Then, these features are optimized by the Q-BGWO for determining the best SVM parameters. Since the current CAD system is more reliable, accurate, and sensitive, its application is advantageous for healthcare. The proposed Q-BGWO-SQSVM was evaluated using diverse databases: MIAS, INbreast, DDSM, and CBIS-DDSM, analyzing its performance regarding accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, precision, F1 score, and MCC. Notably, on the CBIS-DDSM dataset, the Q-BGWO-SQSVM achieved remarkable results at 99% accuracy, 98% sensitivity, and 100% specificity in 15-fold cross-validation. Finally, it can be observed that the performance of the designed Q-BGWO-SQSVM model is excellent, and its potential realization in other datasets and imaging conditions is promising. The novel Q-BGWO-SQSVM model outperforms the state-of-the-art classification methods and offers accurate and reliable early breast cancer detection, which is essential for further healthcare development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cancer is a significant contributor to death globally, especially in the United States, and presents a considerable challenge to increasing life expectancy1. According to the World Health Organization’s 2019 statistics, cancer is the primary or secondary cause of death in 112 out of 183 nations and the third or fourth cause in an additional 23 countries2. In 2020, the International Agency for Research on Cancer (GLOBOCAN) estimated that there were around 19.3 million new cases of cancer and 10.0 million deaths caused by cancer. Out of all the cases, there were almost 2.3 million new instances of female breast cancer, which is the most often diagnosed malignancy, exceeding lung cancer. However, lung cancer continued to be the leading cause of cancer-related mortality, resulting in almost 1.8 million deaths globally. Cancer is defined by the accelerated and unregulated proliferation of cells, which disseminate throughout the body and infiltrate tissues. Tumors are formed as a result of unregulated cell proliferation3. Normal cells undergo division to facilitate tissue repair and are ultimately eliminated from the body.

In contrast, malignant cells exhibit aberrant proliferation, infiltrating healthy tissues and inducing genetic mutations4. Tumors may be categorized into two distinct types: benign and malignant. Benign tumors are characterized by their inability to metastasize and are non-malignant. However, they might develop into masses due to excessive cell proliferation. On the other hand, malignant tumors are carcinogenic and can infiltrate nearby tissues and metastasize to different areas of the body. Female breast cancer is the most common kind of cancer among numerous types, such as lung, liver, colorectal, stomach, and breast cancer (BC)5. On a global scale, around 12.5% of adult women will get a breast cancer diagnosis at some stage throughout their lives. In breast cancer, the illness may arise in several areas of the breast, such as the ducts, lobules, or the surrounding tissues, as seen in Fig. 1, which presents the anatomical structure of the breast.

Anatomy of breast6.

BC is a major worldwide health issue, causing 10 million fatalities and 19.3 million new cases in 2020 alone. This disorder arises from genetic abnormalities that lead to aberrant cell growth, leading to non-cancerous or cancerous tumors. Breast cancer is the second most prevalent form of cancer worldwide and the fifth highest cause of mortality among women. Mammography has been crucial in the timely identification of breast cancer, leading to a considerable decrease in death rates. This is achieved by capturing breast images from two angles: Medio lateral oblique and craniocaudally. This technique classifies breast density into four categories: adipose, dispersed, heterogeneously dense, and very dense7,8. Tumors exhibit a range of forms and borders, with malignant tumors often displaying irregular and unclear boundaries, whereas benign tumors are frequently compact and well-defined. Calcifications exhibit various characteristics; non-cancerous calcifications usually manifest as sizable rods or popcorn-shaped structures, while cancerous ones are spread out or grouped9. Multiple factors contribute to the formation of breast cancer. Figure 2 depicts the variables that impact the occurrence of breast cancer, while Table 1 provides a summary of the many phases involved in the progression of breast cancer. This illness may readily propagate via a woman’s thoracic region, glands, and lactiferous ducts.

Factors affecting Breast cancer disease10.

Early detection and diagnosis of breast cancer greatly enhance survival rates and decrease the occurrence of false positive results, which refer to cases when patients are mistakenly identified as cancer-free. Several diagnostic techniques are used to detect breast cancer, such as mammography, CT scans that utilize X-rays, MRI, and ultrasound, which use magnetic energy and sound waves. Mammography is often the first stage in the identification of breast cancer. However, it may provide difficulties in detecting cancer in women with thick breast tissue; moreover, the radiation released during mammography hazards both radiologists and patients. Similarly, CT scans use radiation that can potentially induce genetic abnormalities in tissues. Ultrasound is the ideal modality for women with thick breast tissue; nevertheless, its reliability is not always consistent, and it is linked to a significantly elevated percentage of false positive results. In order to tackle these issues, biopsies are performed. A biopsy involves a thorough physical examination followed by the extraction of a tissue sample for microscopic analysis. Subsequently, a pathologist examines and analyses this specimen. Histopathology is the meticulous examination of biological cells and tissues using a microscope.

However, the manual inspection of samples by a pathologist is a time-consuming and laborious process, requiring high skills and knowledge. It may result in possible errors related to mental fatigue. For decades, computer-aided detection has been one of the leading systems for diagnosing cancer, successfully overcoming some associated challenges. When it comes to breast cancer examination, ordinary X-ray pictures are applied to distinguish and classify samples of tissues as malignant or benign11. Time-consuming manual examination and classification of breast lesions in mammography rely on the competence and experience of radiologists, which, in turn, may lead to possible errors in diagnosing. The large number of images causes the radiologists’ workload and the rates of mistakes to grow. Recently, some computer-aided detection systems have been developed to improve the degree of accuracy and alleviate the work of radiologists in this field. The computer-aided detection system automatically sorts out regions of interest in mammograms and then classifies them. However, they still have not solved challenges, including the variability in shape and intensity and the problem of overlapping appearance of tissues in mammograms.

The proposed study introduces a novel method for classifying breast cancer that combines an improved Quantum-Inspired Binary Grey Wolf Optimizer (Q-BGWO) with a SqueezeNet Support Vector Machine (SQSVM), offering significant advancements over existing approaches. Unlike traditional methods, which often face challenges such as overfitting, limited adaptability to high-dimensional data, and reliance on extensively annotated datasets, this approach integrates quantum computing principles into nature-inspired optimization, addressing these limitations effectively. By combining the Q-BGWO’s optimization capabilities with SqueezeNet’s efficient feature extraction and SVM’s robust classification, this work establishes a new standard in breast cancer diagnostics.

The novelty of this work lies in its unique hybrid framework, where quantum computational principles such as quantum rotation gates and probabilistic adjustments enhance the search space exploration and convergence speed of the Grey Wolf Optimizer. This advancement allows the model to optimize SVM hyperparameters precisely, ensuring higher classification accuracy and robustness across diverse datasets. Unlike existing nature-inspired algorithms, the Q-BGWO-SQSVM achieves superior accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity performance, outperforming state-of-the-art models across various benchmarks. Additionally, the inclusion of SqueezeNet’s lightweight architecture ensures computational efficiency without compromising diagnostic precision, making it suitable for real-time clinical applications.

Following the analysis and description of quantum computing and its cooperation with nature-inspired algorithms, the study takes critical steps to use the design and mechanisms of the Grey Wolf Optimizer, which represents the strategic behaviors of various organisms in nature to optimize their means of solving complex problems. These behaviors primarily aim to overcome difficulties related to specific survival tasks. The integration of quantum computational capacities enables the optimizer to refine its operation by incorporating quantum characteristics, such as superposition and probabilistic adjustments, to address the challenges faced by traditional methods. Tools such as Grover’s and Shor’s brief factorization algorithms are applied, concretely improving the speed of search and calculation. The study effectively extends the application of classical heuristics to resolving significant engineering and computing tasks through a combination with quantum improvements. This innovative approach not only advances the field of medical image classification but also sets a new benchmark for automated detection of breast cancer, making it a transformative tool in clinical diagnostics.

The innovative contributions of the study include:

-

Developing a novel hybrid framework that combines the Q-BGWO with SqueezeNet-SVM significantly advances the capabilities of automated breast cancer detection systems.

-

Integrating quantum-inspired optimization principles into the Grey Wolf Optimizer enhances its ability to handle high-dimensional, complex data and avoids premature convergence common in traditional metaheuristic algorithms.

-

An efficient feature extraction mechanism using SqueezeNet’s fire modules and bypass mechanisms, ensuring computational efficiency while retaining diagnostic precision.

-

State-of-the-art performance metrics, as demonstrated on diverse datasets such as MIAS, INbreast, DDSM, and CBIS-DDSM, achieve outperformance over existing models in accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity.

-

A practical and scalable solution for clinical diagnostics, reducing reliance on large annotated datasets while maintaining high accuracy and robustness.

Key contributions of the study are:

-

The study addressed issues concerning the external diagnosis of breast cancer through the careful dissection of resource/manual tracking as insufficient for the verification of such matters. Subsequently, a system based on computer vision tools and artificial intelligence for the automated diagnosis of issues, such as the detection of the individual modality, was founded.

-

The study has developed a novel method for classifying breast cancer by integrating a Q-BGWO and a SQSVM. The proposed strategy contributes to improving accuracy at the point of search application.

-

In the first phase of this study, a computer vision algorithm based on pixel-wise segmentation was implemented to accurately extract regions of architectural distortion regions of interest from digital mammogram images.

-

In the next phase, the SqueezeNet algorithm was used to automatically extract features of the abovementioned ROIs and classify them as malignant or benign. Therefore, an optimized support vector machine was used to classify the same effectively, resulting in a comprehensive diagnostic tool.

-

This novel method has been tested with different datasets, such as MIAS, INbreast, DDSM, and CBIS-DDSM, and greatly improved performance metrics can distinguish the results from existing ones. Notably, the Q-BGWO-SQSVM achieved 99% accuracy, 98% sensitivity, and 100% specificity on the CBIS-DDSM dataset, setting a new benchmark for automated breast cancer detection.

-

Achieved outperformance over existing models, delivering higher accuracy and specificity while maintaining sensitivity, thus providing a reliable and efficient tool for early breast cancer detection.

The paper is organized as follows: Sect. “Preliminaries” presents a comprehensive introduction to machine learning algorithms, quantum computing (QC), and nature-inspired algorithms, which serve as the foundation for the subsequent sections. Sect. “Related work” examines a literature review. Sects. “Material and methods” and “Experimental results” discuss the suggested approach and provide the findings from the experiments. Sect. “Conclusions” serves as the final part of the report, concisely summarizing the key insights and conclusions derived from the research.

Preliminaries

Support vector machine (SVM)

SVM aims to identify an N-dimensional hyperplane that classifies the data vectors with minimal error. SVM uses convex quadratic programming to avoid local minima12. Considering a binary classification problem with a training dataset containing class labels: \({(x}_{1},{y}_{1})\)). . . \(n,{y}_{n})\)) xi ∈ \({R}_{d}\) and \({y}_{1}\) ∈ (− 1, + 1), xi represents the feature vector, and yi represents the class label; the optimal hyperplane can be described as follows:

W, x, and b represent the weight, input vector, and bias, respectively. The parameters www and b must satisfy the following conditions:

The primary objective in training an SVM model is to identify values for w and b that maximize the margin \(\frac{1}{{||w||}^{2}}\). Challenges often arise with problems that are not linearly separable. To address this, the input space is transformed into a higher-dimensional space, making the problem linearly manageable.

Kernel functions13 are used to increase the dimensionality of the data, making the issue easier to solve linearly. Kernel functions also make it possible to calculate more efficiently in spaces of higher dimensions. For example, a linear kernel might compute the dot product of two sets of features in this numerical feature space. Radial Basis Function and polynomial are two popular SVM kernels. The following is an explanation of these kernels.

Parameters such as γ and p are significant in the given SVM framework. In particular, while γ denotes the width of the Gaussian kernel, p is the order of the polynomial. According to the outcomes of prior studies, properly configuring these model parameters considerably enhances the accuracy of SVM classification14. Thus, it is essential to gradually fine-tune such significant parameters as C and γ and the selection of the SVM Gaussian kernel function. In turn, such adjustments contribute to increasing the input space’s dimensionality to allow non-linear issues to be construed as linear.

Quantum computing

In quantum computing, the equivalent of a bit is a qubit, which can exist in a superposition of 0 and 1 states. In other words, a qubit |φ〉 can be equal to |0〉 and |1〉 at the same time, with specific probabilities of such states. Most importantly, the superposition principle is ensured since a qubit |φ〉 can be represented as a linear combination of |0〉 and |1〉 states. At the same time, |0〉 is the ground state of a qubit, while |1〉 is the excited one they could be compared to the two binary states of a conventional bit. Therefore, the probability of measuring |0〉 or |1〉 is associated with their coefficients and can be calculated by squaring them within the linear combination after normalizing these states. The normalization condition establishes that the sum of the squared probabilities of any particle is always 1; thereby, the probability conservation is provided. Thus, qubits are used to develop quantum algorithms and help achieve exponentially faster calculations of such activities as factoring large numbers or scanning unsorted databases15. The mathematical qubit is expressed as:

where and are complex numbers that satisfy the normalization condition \(x\)|2 +|\(y\)|2 = 1. In this case, |\(x\)|2 and |\(y\)|2 are the probabilities of finding the qubit as a |0〉 and |1〉 state. Quantum operations on the qubits are mostly done through quantum gates or operators, representing such operators as matrices. Thus, operators enable qubit state manipulation, allowing for the move from one state to another. The primary quantum operators are the Pauli operators: P, X, Y, and Z, as shown in Table 2. Examples of complex gates include Toffoli, Feynman, Fredkin, Swap, and Peres gates that perform vital roles in quantum circuits. Rotation gates such as x-gate, y-gate, and z-gate rotate qubits along the X, Y, or Z axes, and their transformations in matrices form is Mathematically shown16.

Equations 7, 8 introduced in the article show how rotation gates are applied to change the update phases of GWO. To continue the development of algorithms that are influenced by quantum theories, this study also applies the principles of quantum rotation matrices to traditional algorithms. This approach remains novel, and this is the first time quantum mechanics and nature-inspired algorithms have been applied to analyze the outcomes of the interaction and integration of the two discussed approaches in feature selection.

Binary grey wolf optimization

The recent improvements have stimulated the considerable growth of nature-inspired algorithms in many technical domains. The Artificial Bee Colony is the approach developed by Derviş Karaboa that is based on the foraging behavior of honeybees to solve numerical optimization problems. Another solution is the Grey Wolf Optimizer introduced by Seyed Mirjalili17. The latter approach employs the hunting strategies of wolves to improve the found solutions. Meanwhile, the Elephant Search Algorithm relies on the unique search behaviors of male and female groups of elephants. The Artificial Algae Algorithm18 is an innovative platform that leverages the evolutionary processes of microalgae. The Fish Swarm Algorithm19 has also been developed based on how fish schools forage. The GWO algorithm was conducted by Mirjalili et al. in 201417. It exploits the search power of grey wolves with a complex social organization. According to the process, the GWO algorithm involves three best solutions during each iteration. In this case, α, β, and δ start leading and moving the pack to promising areas. The latter is assisted by so-called omegas who participate in exploring and optimizing the search landscape. This well-organized structure allows investigating the search surface and the identification all possible optimal results. The structure of this process is depicted in Fig. 3.

Hierarchy of the grey wolves(GW)17.

The encirclement behavior of Grey Wolves (GW) can be analytically described using the equations below:

In these equations, t denotes the current iteration, \({{\overset{\lower0.5em\hbox{$\smash{\scriptscriptstyle\rightharpoonup}$}} {X} } }_{prey}\) Is the positional vector of the prey, \({\overset{\lower0.5em\hbox{$\smash{\scriptscriptstyle\rightharpoonup}$}} {X} }\) represents the positional vector of the GW, \({\overset{\lower0.5em\hbox{$\smash{\scriptscriptstyle\rightharpoonup}$}} {A} }\) linearly decreases from 2 to 0, and \({\overset{\lower0.5em\hbox{$\smash{\scriptscriptstyle\rightharpoonup}$}} {r} } _{1}\), \({{\overset{\lower0.5em\hbox{$\smash{\scriptscriptstyle\rightharpoonup}$}} {r} } }_{2}\) are random vectors uniformly distributed within the range [0,1]. These equations are crucial in modeling the foraging tactics of grey wolves, as illustrated in Fig. 4.

Grey wolves go through many distinct phases in their hunting activity. The first phase ‘A involves the wolf’s pursuit, approach, and tracking of its prey. When the wolves have located their prey, they will begin harassing and pursuing it in stage B-D. At this point, the pack may form a circle around the victim to keep it from running away. The last step E is to assault the prey while the wolves remain positioned20.

Figure 5 presents the Binary Grey Wolf Optimizer (BGWO) as a flowchart. In the BGWO algorithm, each Grey Wolf possesses a flag vector, the length of which matches that of the dataset. The positions of the Grey Wolves are updated according to Eqs. (10).

where \({{\varvec{X}}}_{{\varvec{i}},{\varvec{j}}}\) Designates the \({\varvec{i}}{\varvec{t}}{\varvec{h}}\) GW’s \({\varvec{j}}{\varvec{t}}{\varvec{h}}\) position.

Related work

Recent advancements have highlighted the potential of expert systems and artificial intelligence in aiding the detection of breast cancer, helping medical professionals avoid costly errors. These systems efficiently process medical data and critically support less experienced doctors. Breast cancer detection has seen notable successes through various artificial intelligence strategies, including21 GWO-based feature selection combined with deep learning for microarray cancer datasets22 ensemble models for predicting breast cancer relapse from histopathological images23 hybrid optimization techniques like Binary Grey Wolf with Jaya Optimizer for biomarker selection 24 fog-empowered transfer learning frameworks such as CanDiag for cancer diagnosis25 chaotic firefly algorithms for global optimization with dropout regularization26 GA-based hierarchical feature selection for handwritten word recognition27 hybrid firefly algorithms for XGBoost tuning in intrusion detection28 improved sine cosine metaheuristics for IoT security using hybrid machine learning models and29 metaheuristic-tuned extreme learning machines tackling IoT security challenges30.

These innovative methods collectively underline the effectiveness of hybrid and metaheuristic approaches in improving diagnostic accuracy and addressing complex challenges in medical and security domains. Despite their success, these approaches often face limitations such as dependency on large datasets, lack of adaptability across varied imaging conditions, and challenges in achieving consistent optimization of hyperparameters in high-dimensional data.

The AMMLP method has recorded an impressive accuracy of 99.26%31. Diagnoses have achieved peak and average accuracies of 100% and 96.87% using an RS-SVM classifier32. A PSO-SVM approach has yielded a 99.3% accuracy rate33. A genetically optimized neural network (GONN) specifically designed for breast cancer detection has used a genetic approach to enhance its structure, resulting in an astounding accuracy rate of 97.73%34. In addition, using genetic algorithms for feature selection has effectively identified the most efficient characteristics of breast cancer for SVM classification, leading to a 95.8% accuracy35. Advanced applications of genetic algorithms have improved breast cancer prediction. These include a genetic algorithm based on tribal competition and an online gradient-boosting strategy for feature selection. These methods have achieved accuracies of 98.32, 94.28, and 95.75% respectively36,37,38. In addition, a differential-evolution algorithm with multi-objective elitism and a skill acquisition technique based on graphs achieved accuracies of 96.86 and 75.05%, respectively, as reported in references33. Ensemble learning algorithms have also been applied, achieving a 97.4% accuracy rate41. An adjusted bat algorithm has optimized SVM parameters significantly, improving classifier accuracy to 96.49% from 96.31% for the WDBC dataset42. A feature selection strategy using GA reached a 96.9% accuracy43. Comparisons among different cancer classification models like naïve Bayes, logistic regression, and decision tree identified the logistic regression classifier as the most effective, with the highest accuracy of 97.9%44. Particle swarm optimization has been utilized to refine the C4.5 algorithm, improving its accuracy to 96.49% from 95.61% for the WBC dataset45. An improved cost-sensitive SVM, considering the unequal misclassification costs of breast cancer diagnosis, achieved a 98.83% accuracy on the WDBC dataset46. Additional techniques, such as the sparse pseudoinverse incremental-ELM, likelihood-based fuzzy analysis, and a dual-stage SVM-driven BC classification, have achieved accuracies of 95.26, 97.28, and 98% correspondingly47,48,49. In addition, preprocessing methods such as resampling, discretization, and handling missing data have been used. This has resulted in classifications using Sequential-Minimal-Optimization, naïve Bayes, and J48 algorithms, with claimed average accuracies of 97.5, 98.73, and 98% respectively47.

While these approaches have made significant strides, their dependence on traditional optimization methods and general machine learning frameworks limits their ability to achieve high performance consistently across diverse imaging datasets. These methods cannot often balance computational efficiency with the complexity of medical imaging data.

The combination of Support Vector Machine (SVM) with Radial Basis Function (RBF) kernel and AdaBoost algorithm classifiers, using nature-inspired algorithms and applying the maximum likelihood principle, has improved the stability of classification. The accuracy rates achieved are 96% for AdaBoost, 97.37% for Particle Swarm Optimisation (PSO), 97.19% for Genetic Algorithm (GA), and 95.96% for Ant Colony Optimisation (ACO), as determined through tenfold cross-validation50,51. Furthermore, the integration of Support Vector Machines (SVM) with K-means clustering has successfully distinguished between cancerous and non-cancerous tumours, with an impressive accuracy rate of 97.38%52. PSO has been successfully applied to the MIAS, WDBC, and WBCD datasets, as reported in datasets53. A study comparing six machine learning approaches achieved a 99.04% accuracy rate54. Augmented by the Levy flying strategy, the fruit fly optimization technique successfully optimized the Support Vector Machine (SVM) parameters and yielded significant outcomes in breast cancer diagnostics55. A novel approach has been proposed56, which combines Support Vector Machines (SVM) with Radial Basis Function (RBF) and polynomial kernel functions, together with the use of the dragonfly method. Two machine learning methods, a decision tree and K-nearest neighbors, were used to build models. These models were trained on data that underwent feature selection using principal component analysis (PCA). The results showed that the K-nearest neighbors classifier performed better than the decision tree57.

Building on these advancements, this study introduces a novel hybrid approach, the Quantum-Optimized Binary Grey Wolf Optimizer-SqueezeNet Support Vector Machine (Q-BGWO-SQSVM), which addresses these limitations by combining the strengths of quantum-inspired optimization with efficient deep learning architectures. Unlike traditional approaches, Q-BGWO-SQSVM leverages quantum mechanics principles for superior hyperparameter optimization, enhancing feature selection and classification accuracy across diverse datasets.

Furthermore, genetic programming and machine learning techniques have resulted in a classification accuracy of 98.24%58. Researchers have developed optimization algorithms for categorizing the Iris and Breast Cancer datasets using Artificial Neural Networks (ANN), showing notable results59. The efficacy of several machine learning models in forecasting breast cancer was assessed using the WDBC dataset. The Support Vector Machine (SVM) model achieved a precision of 96.25%60. In addition, a novel diagnostic model that integrates the batting approach, gravitational search algorithm, and a feed-forward neural network achieved testing and training accuracies of 94.28% and 92.10%, respectively, on the same dataset61.

The unique contribution of Q-BGWO-SQSVM lies in its ability to overcome challenges such as high-dimensional data complexity, overfitting, and dataset variability. By integrating SqueezeNet’s efficient feature extraction with Q-BGWO’s robust optimization capabilities, the proposed model achieves state-of-the-art performance and ensures computational efficiency and adaptability to clinical applications.

A hybrid metaheuristic-swarm-intelligence-based SVM classifier, optimized using grey wolf and whale optimization methods, was evaluated on the WDBC dataset. The classifier achieved a classification accuracy of 97.721%62. Recent studies using the grey wolf optimizer have improved the performance of support vector machines (SVM) in diagnosing breast cancer. These studies have shown that the optimizer achieves rapid convergence and a high accuracy rate of 99.30%63. Efficient scaling solutions for optimizing Support Vector Machines (SVM) are successful for linear programming, as evidenced by references64,65,66,67. A novel parallel swarm approach has been created to address two-sided balancing issues.

Additionally, techniques have been devised to minimize computation time and solution area in conventional processes. These advancements have resulted in notable enhancements in efficiency and accuracy, as shown in previous studies68,69. Metaheuristic algorithms, including ABC, FPA, BA, PSO, and MFO, have optimized SVMs and extreme learning machines, successfully tackling problems related to local minima and overfitting70,71. Numerous research papers have explored a variety of ML algorithms for diagnosing breast cancer, particularly in datasets affected by impulsive noise. A multilayer extreme learning machine method based on full correntropy has been highlighted for its effectiveness72. Efforts to boost ANN performance while simultaneously cutting down on misclassification costs have been encapsulated in the LS-SOED method73. Moreover, logistic regression has been used to select features, in combination with the Data Handling Group Method and a smooth group L1/2 regularisation approach. This strategy seeks to remove unnecessary nodes from the inputs of feedforward neural networks, leading to substantial improvements in accuracy and precision74,75.

A fuzzy inference system that leverages an adaptive network and decision tree methodologies has shown considerable classification accuracies76. Recent advancements in hybrid ML models utilize diverse meta-heuristic optimization techniques, including BBO, GWO, PSO, SCA, ChOA, SSA, WOA, AGPSO, and DA, to solve a broad spectrum of problems. Despite the No Free Lunch theorem suggesting no single metaheuristic algorithm universally outperforms others, specific algorithms have demonstrated greater efficacy for particular applications.

The proposed study seeks to determine how the Q-BGWO-SQSVM architecture categorizes mammographic pictures in the MIAS, Inbreat, DDSM, and CBIS-DDSM datasets. Here, the fundamental image processing methods are meant to eliminate background noise, consequently making the pictures more vivid and defined. Secondly, benign and malignant areas of interest are gathered. For Abnormal, the included aberrations presented in datasets along with their central coordinates indicate, simplify the process of taking square regions that perfectly fit the circumstances. Since Normal is not provided with specific spatial coordinates, the region of the place mentioned before is randomly picked77. These representative samples of both normality and deviancy are relatively distinct. However, their malignant and benign simulated Region of Interest are not easily distinguishable. Therefore, it can be suggested that to make the ‘discernable patterns’ more distinct from the two buckets—normal and abnormal categories BGWO and Q-BGWO could be applied as separate models.

Moreover, the combination of BGWO and Q-BGWO, using the SQSVM, is supposed to give a highly accurate classifier that can tell the difference between malignant and benign breast cancer. This algorithm aimed to automate breast cancer classification, which promises high precision. Figure 5 reflects the entire schematic of our study.

Material and methods

Dataset

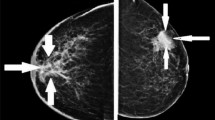

This study evaluates the effectiveness of proposed algorithms by utilizing mammography images from four benchmark datasets: Mammographic Image Analysis Society (MIAS)78, INbreast79, Digital Database for Screening Mammography (DDSM)80, and Curated Breast Imaging Subset of DDSM (CBIS-DDSM)81. Figure 6 displays examples of normal and malignant mammograms from these datasets.

Rationale for Dataset Selection: These datasets were selected to ensure a comprehensive evaluation of the Q-BGWO-SQSVM model across varied imaging conditions, including differences in resolution, imaging formats, lesion characteristics, and annotation precision.

-

MIAS represents a compact dataset offering annotated mammograms with diverse lesion types and associated prognostic data, making it suitable for validating the model’s ability to handle small-scale, annotated datasets.

-

INbreast provides high-resolution images in DICOM format, incorporating expert-annotated benign and malignant lesions, which test the model’s capability to process high-dimensional medical data.

-

DDSM contributes a large dataset of mammograms with detailed patient-specific information, enabling the evaluation of the model’s generalization on extensive datasets with variable patient demographics and density ratings.

-

CBIS-DDSM is an improved version of DDSM, offering binary masks and pixel-level annotations, which allow for precise validation of the model’s feature extraction and classification accuracy.

The MIAS dataset78 comprises 322 mammograms from 161 individuals, including 54 malignant, 61 benign, and 207 normal images. Each image, rendered in 1024 × 1024 pixel grayscale, offers a resolution of 200 microns and is stored in PGM format. This dataset includes diverse mammogram stances and detailed annotations. It features various lesion types and related pathological prognostic data. The dataset also details the ROI, cropped based on the provided coordinates for each anomaly’s center and radius. Only the benign (BIRADS 2, 3) and malignant (BIRADS 4, 5, 6) annotations are considered for this research.

The INbreast dataset79 contains 410 mammography images, incorporating benign, malignant, and normal cases. This collection, saved in DICOM format, includes 192 benign and 107 malignant breast lesions, each delineated with expert precision. Image dimensions range from 2560 × 3328 to 3328 × 4084 pixels, adjusted according to breast size.

The DDSM dataset80, contributed to by institutions like Massachusetts General Hospital and Wake Forest University School of Medicine, includes comprehensive mammography data from 2500 benign and 3000 malignant cases. Each record in this dataset provides detailed patient-specific information such as age, ACR breast density rating, and subtlety assessment of anomalies. The ground truth data in the DDSM offers detailed descriptions of lesion locations and types at the pixel level, with 200 ROIs associated with both benign and malignant images.

The CBIS-DDSM81, an improved version of the DDSM curated by the University of Florida, provides a public repository of mammography images in DICOM format. This dataset includes 3,568 mammograms, showcasing 1740 benign and 1828 malignant cases. Each image offers dual views (MLO and CC) and is accompanied by binary mask pictures that delineate the anomalies for precise ROI identification, allowing for exact pixel-level analysis of the irregular areas.

Image preprocessing

Breast lesions within the breast tissue present a high risk of misdiagnosis9. These lesions are typically recognized by their shape, size, and boundary characteristics, and they appear lighter than the surrounding tissue82. This study’s preprocessing steps include noise reduction using adaptive median filtering, morphological operations for boundary refinement, and Contrast Limited Adaptive Histogram Equalization (CLAHE) to enhance image clarity. Parameters for noise reduction include a window size of 3 × 3 for initial filtering, which expands to 7 × 7 if outliers persist. Morphological operations, specifically erosion and dilation, use a 3 × 3 structuring element to remove non-breast regions while preserving critical features effectively. To monitor the development of significant lesions, radiologists often compare mammograms of the same breast taken over time. Identifying suspicious lesions over time involves spotting key control points like the edges of shapes caused by tissues, arteries, and ducts and analyzing the connections involving these points in sequential images. Adapting deep learning techniques to analyze such complex environments is crucial in medical image processing. Preprocessing of images is crucial to increase the contrast between normal and pathological images in mammograms by reducing the noise and improving the image clarity. Such preprocessing includes noise reduction, enhancements, scaling, and cropping of images, which is essential before implementing a learning-based algorithm to avoid overfitting. This paper does image enhancements such as averaging, median filtering, morphological operations, and CLAHE to increase the readability of mammogram images.

The region between the breast area is identified, affecting the adjacent tissue, using the global thresholding method. Probably, this refers to the application of a threshold value T on the mammography image I(x, y), and the pixels with values greater than the threshold value are considered to be a breast and the other a non-breast, where I(x, y) > T represent the breast region. As an experienced radiologist, the threshold level here is about 30.

Image acquisition

Compiling a vast assortment of mammography pictures presents substantial logistical challenges. Mammograms in their original state often include patient information, inherent interference, and fluctuations in illumination, which might result in a greater occurrence of incorrect positive results. Typically, these photos are transformed to grayscale in order to preserve important information throughout other modifications. The inherent limitations of mammography may have a negative impact on the effectiveness and education of deep learning algorithms. Moreover, a lack of breast photos sometimes results in overfitting during model training. Deep learning systems need a large number of annotated mammograms, but the task of annotating these pictures is both time-consuming and expensive83.

During data acquisition, morphological operations such as opening and closing eliminate labels and annotation tags. Erosion and dilation, fundamental morphological techniques, reduce and enlarge the elements of an image, respectively. Erosion is defined as the compilation of all points P such that the structuring element S fits within the set E when translated by P:

Dilation involves expanding E with the structuring element \(\widehat{S}\), organizing all displacements P so that SSS and EEE intersect at least once:

These operations are crucial for preserving image features:

Equations 17, 18 remove labeling and annotation markers from mammography images.

Image Noise Reduction and contrast enhancement

Post-acquisition, mammography images undergo processing to remove noise. Various noise types such as Gaussian, salt and pepper, speckle, and Poisson are reduced using an adaptive median filtering technique, resulting in a noise-free image Inf. The process begins by determining the maximum and minimum pixel intensities within a window, denoted as \({MaxP}_{\omega }\) and \({MinP}_{\omega }\), respectively. If the median \({Med}_{\omega }\) If the window is not an outlier, the process moves to the next verification step; otherwise, the window size is increased until the median is not an outlier or the maximum window size is reached. If Inf falls within the range \({MinP}_{\omega }\)< \({I}_{nf}\)< \({MaxP}_{\omega }\), the image resolution remains unchanged; if not, the median value from step 2 is used.

Following noise reduction, image contrast enhancement is necessary as boundaries in noise-free mammography may fade. Edge-stopping functions prevent diffusion in areas of low image gradient, preserving sharp edges and enhancing detail. The edge-stopping function and the diffusion constant K are given by:

This function also helps maintain the object’s edges while reducing noise. Histogram equalization is applied to boost global contrast, particularly enhancing relative contrast values crucial for imaging data. A histogram represents the distribution of digital image pixels across grey levels:

This equation demonstrates anisotropic diffusion histogram equalization, estimating the likelihood of each grey level \({\varvec{g}}{\varvec{l}}\) within the image.

Data-augmentation

CAD systems are capable of detecting and categorizing breast lesions. However, they frequently face high false-positive rates84. Conventional techniques that depend on traits created by humans are not sufficient for the precise identification of abnormalities85. The limited availability of annotated pictures for deep learning models results in overfitting86 and difficulties in training owing to the significant expense and time needed for human annotation87. Previous methodologies had trouble handling the data’s intricacy88. Figure 7 illustrates the suggested method for enhancing the detection and classification of breast cancer. This work utilizes data-augmentation methods such as geometric adjustments and patch extraction to enhance picture datasets, as shown in Table 3. Each augmentation technique was applied sequentially with the following parameters: sharpening intensity ranged from 0.5 to 2, Gaussian blur was applied with variances of 0.25, 0.5, 1, and 2, and rotations were set at intervals of 45° (e.g., 45°, 90°, 135°, and 180°). Skewing was performed in four directions: left, right, forward, and backward, with offsets of 10 pixels. Shearing transformations were limited to ± 10° along the X-axis and Y-axis. Flip transformations included left–right and top–bottom inversions to maximize dataset variance. Patch extraction involved splitting images into non-overlapping tiles of 256 × 256 pixels to improve spatial diversity during training.

Lesion segmentation

Breast segmentation is critical in mammography analysis because it removes artifacts, pectoral muscles, and background noise that could hinder anomaly detection. This process divides the mammogram into regions of interest (ROIs) for more effective feature extraction from breast anomalies. However, inaccurate segmentation can lead to poor feature selection, subsequently causing errors in classification. The segmentation of breast masses is typically performed based on attributes like intensity, texture, shape, and presence of anomalies. A method was introduced89 to classify lesions by these characteristics since clinically precise mass boundaries are often unattainable. Another study90 applied a thresholding technique to enhance edge detection in mammograms, identifying the Otsu method as the most effective for mammogram segmentation. Threshold segmentation is the prevalent method for isolating breast lesions; it categorizes lesion pixels based on a set threshold value. This approach is convenient for images exhibiting diverse grayscale levels. Due to its simplicity, rapid computation, and ease of implementation, threshold segmentation is a fundamental preliminary step before extracting image features and conducting further analysis. This research utilized the Otsu thresholding model91 to delineate potential mass areas within mammograms. The Otsu method primarily utilizes the intensity data of the image, disregarding its shape and geometric properties, which facilitates the segmentation of the relevant regions for detailed pixel-level investigation. The method effectively binarizes the image by splitting its pixels into the object (foreground) and backdrop (background) based on the optimal threshold set by the adopted thresholding technique, as depicted in Fig. 8. This study set thresholds when performing segmentation on an image. The purpose is to divide pixels according to different thresholds to obtain several sets of pixels. Each set may provide information about the image’s specific structure or texture, and each region’s pixels share the same features while those of neighboring regions varied. The algorithm’s precise process is as follows:

-

The Otsu technique needs the threshold T to divide a mammogram with a grey value range of 298 [0, 1 − L] into two halves, C1 and C2, with C1 corresponding to the grey value range [0, T] and C2 corresponding to the grey value range [T + 1, L − 1].

-

Calculate the pixel average grey values µ1 and µ2 for areas C1 and C2, as well as their respective proportions ω1 and ω2 to the whole image pixel, and then calculate the grey average value µr for the entire image pixel described in Eq. 18.

$$\mu_{r} = \, \omega_{1} \mu_{1} + \, \omega_{2} \mu_{2}$$(18) -

Compute the total variance \({\sigma }_{r}^{2}\) of regions C1 and C2, described in Eq. 19.

$${\sigma }_{r}^{2}={\omega }_{1}{({\mu }_{1}-{\mu }_{r})}^{2}+{\omega }_{2}{({\mu }_{2}-{\mu }_{r})}^{2}={\omega }_{1}{\omega }_{2}{({\mu }_{1}-{\mu }_{2})}^{2}$$(19)

T takes on consecutive values between [0, 1 − L]; hence, the value of \({\sigma }_{r}^{2}\) fluctuates continually. Larger the value of \({\sigma }_{r}^{2}\), the greater the contrast between the foreground and background. The calculation stops when \({\sigma }_{r}^{2}\) reaches its maximum value. Suppose T0 is the threshold that corresponds to the highest variance. In that case, this threshold is the optimal segmentation threshold because it effectively distinguishes the foreground from the background and has the lowest misclassification probability.

Quantum-inspired binary grey wolf optimization

While the conventional GWO uses continuous values in the [0,1] range to guide the wolves’ positions, the BGWO transforms each wolf’s position into a binary format using a sigmoid function on the former92. To solve the unit commitment challenge, a BGWO version referring to the quantum approaches was launched and called Q-BGWO. The novel approach takes advantage of the quantum-inspired mechanism by which each wolf’s position is binary and affected by a specific qubit vector that was combined with a quantum rotation gate. This transformation is made possible owing to an adjustment specified with the help of the y-gate (θ) in Equation. The new solution is fundamentally different from the conventional GWO because while the latter adjusts wolves’ positions following Equations A and C, the quantum approach makes the required adjustments based on the relevant qubit and the rotation angle θ that can be calculated with the help of two random probabilistic values, γ and ζ.

The α, β, and δ wolves are allocated random coefficients λ1, λ2, and λ3, respectively. The theta magnitude for the α wolf is represented by ζα. These coefficients determine the rotation angles for each wolf’s qubit vector, designated as Q. The rotations are performed based on Eqs. (26), (27), and (28), which specify the adjustments made to the location of each wolf following their respective rotation degrees.

Q is a quantum state vector that forms a single qubit.

Initially, the coordinates \({\left(x\right)}_{\alpha }\), \({\left(y\right)}_{\alpha }\), \({\left(x\right)}_{\beta }\), \({\left(y\right)}_{\beta }\), \({\left(x\right)}_{\delta }\), and \({\left(y\right)}_{\delta }\) are all set to 0.5. Updates to the wolves’ positions are then governed by the likelihood of their corresponding qubit vectors being in the state |1〉. This method aligns with the quantum behavior of the system, where each position change reflects the quantum probability calculations.

The binary conversion of the wolves’ positions in the BGWO involves straightforward thresholding operations. The position update equation is represented as:

The following process converts probabilistic values into binary outcomes. The process compares each value with a threshold, which is squared. The threshold is derived from the probability of the qubit being in the state. After thresholding, a binary value of each feature is determined by a majority voting process between the alpha (α), beta (β), and delta (δ) wolves. The feature is chosen if most of these wolves assign a value of ‘1’ to it. Otherwise, the feature is rejected. Thus, a binary feature vector \(\left( {\overset{\lower0.5em\hbox{$\smash{\scriptscriptstyle\rightharpoonup}$}} {X} } \right)\) is created in order to represent the chosen features that are essential for solving the problem. The binary feature vector \(\left( {\overset{\lower0.5em\hbox{$\smash{\scriptscriptstyle\rightharpoonup}$}} {X} } \right)\), is then passed on through another process which involves finding the sigmoid function:

where p ranges from 0 to 1. This function helps soften the thresholding process, providing a smoother transition between binary states.

The resultant values are then compared to a randomized threshold s, ranging from 0 to 1, to finalize the binary states of the features:

This step is crucial for ensuring that the feature selection process is robust and aligns with the probabilistic nature of quantum-inspired computations.

Pseudo Code: Quantum Binary Grey Wolf Optimization (QBGWO)

Input: |

`N`—Total number of wolves (Population size) `D`—Dimensions of the search space `T`—Maximum number of iterations `f`–Fitness evaluation function |

Output: |

`α`—Optimal solution discovered |

Procedure: |

1. Initialize Population: Create population `ρ` with `N` wolves, each with a D-dimensional binary vector For each wolf `F_i` in `ρ`: For each dimension `d` from 1 to `D`: `F_i[d] = GenerateBinary()` 2. Assign Roles: Order wolves by their fitness using `f` Designate roles: α (Alpha), β (Beta), δ (Delta), ω (Omega) based on fitness order 3. Initialize Qubits: For each wolf `F_i` in `ρ`: Initialize a qubit vector `Q_i` with values `|0⟩` and `|1⟩` having equal probabilities 4. Update Positions Using Quantum Gates: For iterations `t` from 1 to `T`: Adjust control parameter `a`: `a = 2 * (1—t / T)` For each wolf `F_i` in `ρ`: For top roles `F_p` in {α, β, δ}: Set vectors `A` and `C`: `A = 2 * a * GenerateVector()—a` `C = 2 * GenerateVector()` Compute distance `K` from `F_p` to `F_i`: `K =|C * position of F_p at t—position of F_i at t|` Update position for the next iteration: `F_i[t + 1] = position of F_p at t—A * K` Update qubit vector `Q_i` using rotation gates: For each dimension `d` from 1 to `D`: Apply rotation gate `R(θ)` to `Q_i[d]` Update `Q_i[d]` based on the new angle `θ` Use a sigmoid function for binary transitions: For each dimension `d` from 1 to `D`: `probability = Sigmoid((Q_α[d] + Q_β[d] + Q_δ[d]) / 3)` `F_i[d][t + 1] = 1 if GenerateRandom() < probability else 0`Reassess fitness and readjust roles: For each wolf `F_i` in `ρ`: Update α, β, δ based on new fitness evaluations 5. Finalize: Return the α with the best fitness |

SqueezeNet- SVM

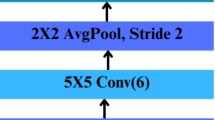

SqueezeNet93 was selected as the foundational architecture for this study due to its compact size and low number of parameters, making it highly efficient for training on limited computational resources. SqueezeNet operates with significantly fewer parameters than larger models: AlexNet has 61 million, VGG-16 features 138 million, Inception-v3 holds 23 million, ResNet-50 has 25 million, and MobileNet comprises 4.2 million parameters. In contrast, SqueezeNet has only 1.2 million, enabling it to efficiently handle large datasets, such as mammography images, which require substantial computational power due to their high resolution and complexity. Additionally, its architecture is particularly effective in detecting subtle patterns, such as those found in breast cancer features. This streamlined architecture does not compromise on performance, maintaining comparable accuracy to its larger counterparts in image classification tasks94.

The fire module is the centremost part of a SqueezeNet, which is a small and flat convolutional network. As illustrated in Fig. 9, its purpose is to analyze the information to be retained efficiently. Specifically, it performs compression to reduce the number of input channels and expand to develop them. This mechanism plays a crucial role in processing mammography images by efficiently reducing redundant data while emphasizing critical features that are indicative of breast cancer. As the corresponding source describes, the compression feature reductions rely on 1 × 1 convolution, and the expansion development comes with both 1 × 1 and 3 × 3 convolutions. In this way, the channel count is increased with 1 × 1 and 3 × 3 convolutions, which means bypass links can capture the finer details and changes in the input. Otherwise, very little useful information can be gained from it.

In addition, the SqueezeNet is equipped with sophisticated bypass links designed to improve the transmission of information across the network, as indicated in Fig. 10. These bypass mechanisms allow for improved retention and transmission of intricate details found in mammography images, ensuring that fine-grained patterns relevant to breast cancer detection are preserved throughout the layers. Specifically, these links allow for direct data transport to profiles from one level of detail to another, bypassing many layers. The corresponding bypass links can be defined in the following way: Let X be an input feature map and F be the corresponding transform form. The traditional bypass link can be formally expressed as y = x + F(x), x is the output of such a bypass link, while the operator “+” signifies that the two profiles are combined element-wise. In this way, any bypass link’s input and output can be combined to provide the same fundamental details to the upgraded profile—including the differences. This property is critical for mammography, where subtle variations between normal and abnormal tissues are essential for accurate classification. Finally, SqueezeNet allows efficient and effective feature retention functions thanks to the Fire Module and several bypass link parameters. These unique design elements make SqueezeNet particularly suited for extracting distinct features from mammography images, as it balances computational efficiency with the ability to detect subtle patterns characteristic of breast cancer. In turn, the SGS model can identify fine-grained patterns and improve the accuracy and reliability of normal path charge detection.

This study seeks to classify the pictures from breast cancer datasets. The images will be trained to characterize the traits generated by SqueezeNet. The Support Vector Machine is one of the most popular binary classifiers and is well known for its maximum precision of linear and non-linear classification issues. Additionally, it might be pretty efficient in multi-class conditions. The fundamental principle used in applying Support Vector Machines is to create one or more hyperplanes in the input space that might identify multiple classes appropriately. The linear determination hyperplane is expressed as: where w is the weight vector, b is the bias, wT denotes the transpose of the weight vector x is the input vector that contains the parameters of an input feature. The prime purpose of the classification duties in SVM is to choose the perfect hyperplane so that the data points lead the class. It should also enhance the capacity for separation.

The margin is the gap between the nearest data points and the hyperplanes for all classes. It was noted that a larger margin indicates that newer data points have less impact on a classifier. There is no real variance due to details as the points are defined as optimal separation95. Thus, SVMs work to minimize the margin exactly and to ensure good classification between class and data transition. Optimal changes in the value of w and b normally do this.

The input vector is denoted as xi, and the corresponding output label is denoted as yi.

In Support Vector Machines, \({\sigma }_{i}\) Is the slack variable, allowing certain training samples to be mishandled to a limited extent. It includes the C parameter that measures the weight assigned to punishing inappropriate classification. It also supports finding the best balance between incorporating the highest margin within two classes and the ability to classify each of the training samples appropriately. It serves to give the penalty value for misclassification. The variable n is the number of all training samples. \(\frac{1}{2}{w}^{T}w\) is the first component of the target function, and its role is to maximize the margin, while the second one, C \(\sum_{i=1}^{n}{\beta }_{i}{\sigma }_{i}\), is responsible for handling the punishment value for the misclassified training samples. The Lagrangian dealing with this optimisation task can be presented in the following manner:

In order to find optimal values for w, b, and ζ in an SVM formulation by Lagrange multipliers α = (α1,…, αn) and β = (β1,…, βn) have to set up and solve a system of equations by taking partial derivatives of Lagrangian L concerning these variables and setting them to zero, this calculative process can be described in the following way:

The dual Lagrangian may be obtained by using the Karush–Kuhn–Tucker condition49:

In non-linear SVM, kernel functions transform input data into a higher-dimensional space, enabling the algorithm to identify a separating hyperplane in this new space, even if the data cannot be separated linearly in the original space. The optimization issue in non-linear SVM is similar to that of linear SVM, but it involves using a kernel function. The optimization problem may be expressed as follows:

G(xi, xj) represents the kernel function in this context. Among the most commonly utilized kernel functions is the Gaussian kernel:

φ is a hyperparameter that regulates the level of smoothness in the decision boundary. A polynomial kernel is a function used in machine learning and support vector machines. It is a mathematical function that calculates the similarity between two data points in a higher-dimensional space:

d represents the degree of the polynomial. The symbol “h” represents a variable that determines the extent of the polynomial expansion.

SQSVM- optimization

It is crucial to discretely optimize the SVM parameters for optimal performance of SVM classifiers, particularly in complex image classification tasks. The optimization process is based on Grey Wolf Optimizer, which is a metaheuristic algorithm based on the social hierarchy and hunting behavior of Grey Wolves. The process involves several step-by-step results, which are very technical, to ensure the efficiency of the SVM operation.

First, the initialization step involves the creation of a randomly organized population of Grey Wolves—where each Grey Wolf is indicative of a specific array containing a 2-dimensional representation of a particular SVM parameter. This array contains the penalty factor, C, which is the most significant SVM parameter to optimize, and kernel parameters, when applicable, present critical information to the working of the classifier, which is conserved within the dimension. A separate step is applied to define the respective operational parameters of the Quantum-enhanced Binary Grey Wolf Optimizer (Q-BGWO), the improved version of the Grey Wolf Optimizer incorporating principles of quantum mechanics. The Q-BGWO introduces quantum behaviors, such as superposition and probabilistic adjustments, allowing the optimizer to explore the search space more comprehensively and avoid premature convergence. This approach significantly enhances the algorithm’s ability to handle high-dimensional, complex data, such as mammography images in breast cancer classification.

The utilization of Q-BGWO in this context is motivated by its ability to balance exploration and exploitation during the optimization process effectively. By integrating quantum mechanics principles, such as quantum rotation gates and qubit state vectors, Q-BGWO achieves a broader search capacity and faster convergence. This ensures the selection of optimal SVM parameters, such as CCC and kernel parameters, with higher accuracy and robustness, which is crucial for improving breast cancer classification performance. Compared to traditional metaheuristic algorithms, Q-BGWO excels in navigating complex optimization landscapes, reducing the risk of local optima, and delivering precise feature optimization.

Next, the respective operational parameters of the Quantum-enhanced Binary Grey Wolf Optimizer are comprised of the population size, the number of iterations, and the preannouncement requirement to commence. The operational parameters of the SqueezeNet-SVM, which is the SVM model, are initialized. After initialization, the fitness function is used to determine the effectiveness of the operation of each configuration based on the classification accuracy of the SVM model achieved by the cross-validation test. Cross-validation testing is meant to evaluate the ability of the model to generalize, divided into the folds present in K -fold scales of 5, 10, and 15. This mitigates overfitting and is meant to test the applicability of the SVM on datasets. Correspondingly, feature selection operations are optimized by applying the constant q = 1 – e, where q varies from 0, increasing to 1 gradually, which controls the exponential decay of the number of features to ensure optimal computational efficiency and accuracy. The final configuration of the number of features that participates in the modeling, denoted as R, and the total number of features for selecting the data subsets are selected maximally to focus the model on the most probable, most informative attributes.

Subsequently, the fitness of the classified operations of each population of Grey Wolves is tested based on the SVM classification accuracy on the validation folded datasets. At the end of each iteration, the Grey Wolves classification is conducted and evaluated – with the top three best performers ranked as the alpha, beta, and delta associated with the most optimal sets. Using this hierarchical ranking to change the dynamic space of all the wolves in the population ensures the optimal parameters are identified. The iterative process is continued until the optimal parameter configurations are identified or the operation of parameter learning ability on the classifier, which can be evaluated, has been completed. The final chosen configurations are applied in the SQSVM, and the testing of the operational efficiency of the classifier on the testing set confirms the analytical applications in real-time tasks.

Performance evaluation matrices

Various performance metrics typical of many preceding studies are applied to provide a verifiably accurate assessment of the Q-BGWO-SQSVM model and theBGWO–SQSVM model. It should be mentioned that evaluation of a model’s effectiveness includes testing it not only based on its training scores but also through its ability to provide accurate performance on the new data in the future. A set of evaluative indicators is selected to assess the performance whenever a new model is developed.

Sensitivity \(\left(\frac{\text{TP}}{\text{TP}+\text{FN}}\times 100\text{\%}\right):\) is an evaluation of a model’s ability to identify the positive cases of predicting a target class attribute or variable in such a way, measuring the model’s ability to recognize all of the positive instances.

Specificity \(\left(\frac{\text{TP}}{\text{TP}+\text{FN}}\times 100\text{\%}\right)\): is defined by. This method is prescript to sensitivity, as it measures a model’s ability to identify non-positive or negative instances. The method is applied to assess how much a model’s positive and negative predictions are accurate.

Accuracy \(\left(\frac{\text{TP}+\text{TN}}{\text{TP}+\text{TN}+\text{FP}+\text{FN}}\times 100\text{\%}\right)\)—Specified as evaluating the ability to make correct predictions and outcomes on both positive and negative instances. The method relies on performance evaluation in terms of precision and recall.

Precision \(\left(\frac{\text{TP}}{\text{TP}+\text{FP}}\times 100\text{\% }\right):\) is defined as being focused on measuring exactness in positive predictions.

F1-Score \(\left(\frac{2\times \text{Precision}\times \text{Recall}}{\text{Precision}+\text{Recall}}\times 100\text{\% }\right) :\) Defines a harmonic mean of precision and recall evaluation and is useful when a class distribution imbalance is visible. In this way, whenever either precision or recall is strangely high and the other—low, the harmonious mean provides a balanced metric that indicates the advantages and disadvantages of both methods.

Matthews correlation coefficient \(\left(\frac{\text{TP}\times \text{TN}-\text{FP}\times \text{FN}}{\sqrt{(TP+FP)(TP+FN)(TN+FP)(TN+FN)}}\times 100\text{\% }\right) :\) is defined by the formula. The method is particularly applicable when class sizes are imbalanced and unequal. It offers a balanced measure that includes sensitivity, precision, true positives, false positives, and false negatives.

Experimental results

This section presents a detailed examination of the experimental results of studying the datasets utilizing mammography data. This research assesses the proposed technique’s effectiveness in the breast tumor categorization field.

Implementation details

This study used the MATLAB platform and GPU acceleration to analyze the most efficient classification algorithms: the Q-GBGWO based on the SVM. The experimental settings were related to a high-performance fusion: the Intel Core i7 13th generation central processing unit, 32 GB RAM, and a robust NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3090 Ti graphics processing unit. At the same time, the Q-GBGWO was altered in terms of the SVM parameters, which was explained by a higher appropriateness for the classification task.

Cross-validation through 5, 10, and 15 folds ensured the model assessment’s reliability using different datasets. In this regard, the optimizer, functioning within [0,1] as the initial domain and with a consistent population size of 10, can be described as the one dynamically adjusting the SVM’s penalty parameter C for obtaining a coherent level of complexity and the trade-off concerns related to the differences in training errors. Various types of kernel applications, such as Linear, RBF, Polynomial, and Sigmoid, were applied to provide opportunities for both types of data separations, linear and non-linear. Moreover, the weighting parameters, such as α = 0.97 and β = 0.03, were tuned for the optimal balance between exploration and exploitation and to increase the algorithm’s convergence rates using all the best-fitted conditions specified. The performance was measured by the best-fitted optimal iterations varying from 7 to 60 and the corresponding fitness values ranging from 0.0135 to 0.1077—the critical pictures of the classifier’s highest precision. Finally, the qubit vector set was created around [0.5, 0.5] for α-the wolf to implement the most optimal approach for balanced quantum computing and allow the classifier to obtain high classification accuracy as a ready solution with robust specificity problems.

Assessment of Q-GBGWO compared to traditional bio-inspired optimization methods

This research assesses the efficacy of the Quantum Grey Binary Grey Wolf Optimizer (Q-GBGWO) in comparison to conventional bio-inspired algorithms such as the Binary Grey Wolf Optimizer (BGWO), Grey Wolf Optimizer (GWO), and Particle Swarm Optimisation (PSO). For this comparison, we performed testing using the benchmark functions17,96. Every algorithm was executed following the requirements given in their respective foundational texts. The findings in Table 4 demonstrate that Q-GBGWO consistently outperforms other methods, exhibiting greater performance across numerous tests. Although the specific specifics of how each function is carried out align with the processes and results shown in Table 4, Q-GBGWO has demonstrated significant efficacy across several benchmarks. While BGWO, GWO, and PSO have shown competence in certain activities, Q-GBGWO has exhibited comparable or higher effectiveness in most assessed functions. The forthcoming figures, such as Fig. 11, will illustrate the convergence trends of Q-GBGWO. These trends will demonstrate the adaptability and effectiveness of Q-GBGWO during both the initial and later phases of the iterations. They will emphasize the well-maintained balance between exploration and exploitation in optimization.

Cross-validation results

This study used several cross-validation (CV) methods for optimal outcomes and reliable validation. A tenfold cross-validation was used due to its continuous delivery of excellent outcomes. The whole dataset was randomly partitioned into 10 sections of equal size. Throughout the training phase, nine subsets were used, with the final subset designated as the validation set. The technique was repeated 10 times, with each subset utilized for validation once, in order to achieve comprehensive validation across all subgroups. Furthermore, for accurate validation, we conducted fivefold and 15-fold cross-validation and documented their respective results in Fig. 12.

The comparative analysis focusing on the Q-BGWO-SQSVM model across three different cross-validation schemes—fivefold, tenfold, and 15-fold—as revealed through the study of diverse medical image datasets such as MIAS, INbreast, DDSM, and CBIS-DDSM, highlights its exceptional performance. This proposed model has demonstrated top-tier results, consistently outperforming other evaluated models in every key metric: Accuracy (ACC), Sensitivity (SEN), Specificity (SPC), Precision, F1 Score, and Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC).

The Q-BGWO-SQSVM model achieved the highest values for ACC, SEN, SPC, Precision, F1 Score, and MCC and showed remarkable stability and reliability across all datasets and metrics. Its performance underscores its suitability for handling intricate medical image analysis tasks, making it an ideal candidate for applications requiring high precision and reliability in clinical and diagnostic settings.

Throughout the evaluation process over various cross-validation folds, the Q-BGWO-SQSVM model exhibited robustness and adaptability, effectively addressing dataset-specific nuances and maintaining consistent performance. This adaptability is crucial for applications in medical image analysis, where varying data characteristics can significantly impact the efficacy of machine learning models.

The insights gleaned from this study suggest that the Q-BGWO-SQSVM model holds significant promise for enhancing diagnostic accuracy and clinical decision-making in healthcare. Further validation on independent datasets and continuous fine-tuning are recommended to fully capitalize on its capabilities and ensure its reliability and applicability in real-world medical imaging scenarios. This approach reaffirms the importance of advanced machine learning techniques in driving forward the fields of medical diagnostics and personalized medicine.

Performance comparison of proposed algorithm with ML models across different cross-validation schemes

For the MIAS dataset, the 5-Fold Cross-Validation results showcase varying performance levels among different models. The Q-BGWO-SQSVM model exhibits the highest performance, achieving an accuracy of 0.97, sensitivity of 0.96, and specificity of 0.98. These results underscore its superior capability in effectively diagnosing medical images compared to traditional models like SVM and newer variants such as SQSVM and BGWO-SQSVM, which also perform robustly but do not reach the peak metrics of the Q-BGWO-SQSVM. Expanding the analysis to 10-Fold Cross-Validation, there is a noticeable improvement across all models, indicative of the increased data utilization enhancing model training and testing robustness. The Q-BGWO-SQSVM continues to lead with exemplary metrics, including a near-perfect accuracy of 0.98. This enhancement across the board suggests that models can generalize better with more comprehensive cross-validation, with less variance in performance due to the increased data exposure during training. With the 15-Fold Cross-Validation, the trends observed in the 10-Fold validation continue, with even slight metric increments for models like SVM, SQSVM, and BGWO-SQSVM. The Q-BGWO-SQSVM reaches peak performance metrics, maintaining top scores with an accuracy of 0.99, reinforcing its robustness and consistency across different validation folds. This highest level of validation provides a more stringent test of the models’ abilities to maintain performance, suggesting the Q-BGWO-SQSVM’s potential utility in clinical settings where high reliability is paramount.

Across Table 5, the progression from 5-Fold to 15-Fold Cross-Validation demonstrates a general trend of increasing performance, highlighting the importance of model training and validation on larger subsets for stability and accuracy. The Q-BGWO-SQSVM not only consistently outperforms other models but also shows minimal performance degradation as the complexity of the validation scheme increases. This suggests that the model’s architecture and underlying algorithms are well-suited for tackling complex patterns in medical imaging data, potentially due to superior feature extraction capabilities and optimization strategies that mitigate overfitting more effectively than its counterparts. These insights into the model performances on the MIAS dataset across varying cross-validation schemes illustrate the significant impact of sophisticated modeling techniques and rigorous validation on enhancing diagnostic accuracies in medical image analysis.

In the INbreast dataset under 5-Fold Cross-Validation, the performance metrics vary across models, with the Q-BGWO-SQSVM again showing the highest performance, achieving nearly perfect metrics that emphasize its robust feature extraction and classification capabilities. This model achieves remarkable accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity, demonstrating its effectiveness in handling INbreast’s imaging complexities compared to more conventional models such as SVM and RF, which exhibit competitive but slightly lower performance metrics. The 10-Fold Cross-Validation results for the INbreast dataset indicate improvements in model performance, which can be attributed to a more comprehensive utilization of the dataset during the training phase. The Q-BGWO-SQSVM continues to excel with the highest scores, illustrating its consistent performance and reliability. This trend highlights the model’s capacity to effectively leverage more extensive training data, enhancing its predictive accuracy and generalizability. Moving to 15-Fold Cross-Validation, there is a further enhancement in performance metrics across all models, particularly noted in the Q-BGWO-SQSVM, which maintains its superior metrics amidst more rigorous validation. This level of validation tests the models under stricter conditions, confirming the Q-BGWO-SQSVM’s superior adaptability and robustness in clinical diagnostic settings.

Throughout the INbreast dataset analysis in Table 6, increasing the cross-validation folds consistently improves all models’ performance, with the Q-BGWO-SQSVM model maintaining the lead. This pattern supports the inference that higher cross-validation folds reduce overfitting and provide a more reliable estimate of model performance, especially evident in the advanced modeling and optimization techniques employed by the Q-BGWO-SQSVM.

For the DDSM dataset, models exhibit an upward trend in performance metrics as the number of folds increases from 5 to 15 as presented in Table 7. The Q-BGWO-SQSVM showcases exemplary performance across all metrics, with other models like SVM and GB also showing significant improvements. The consistent enhancement in sensitivity and specificity indicates these models’ effectiveness in distinguishing between normal and pathological findings in DDSM’s complex imaging data.

In the CBIS-DDSM dataset, the Q-BGWO-SQSVM’s dominance continues, with peak performance metrics in the 15-Fold Cross-Validation setting, demonstrating near-perfect scores as presented in Table 8. This model’s effectiveness is particularly noteworthy in a dataset known for its challenging diagnostic images, proving its potential in high-stakes medical environments where diagnostic accuracy is critical.

For both DDSM and CBIS-DDSM datasets, increasing the validation folds improves the metrics across models and reinforces the benefits of robust cross-validation in achieving high generalizability and reliability. The consistent performance of the Q-BGWO-SQSVM across these datasets underscores its superior architectural and algorithmic framework, which is ideal for complex and high-dimensional medical imaging tasks. These evaluations reveal how advanced machine learning models, especially the Q-BGWO-SQSVM, adapt and perform under rigorous testing conditions, offering insights into their practical applications in medical imaging and diagnostics.

AUC comparison proposed algorithm with traditional ML algorithms

The ROC curve is a critical evaluation tool in assessing the effectiveness of classifiers in distinguishing between patients with a disease and those without it. The Area Under the Curve (AUC) is a crucial metric derived from the ROC curve, with higher AUC values indicating better discrimination capabilities of the model. In our study, we present ROC curves for four datasets: MIAS (Fig. 13A), INbreast (Fig. 13B), DDSM (Fig. 13C), and CBIS-DDSM (Fig. 13D), evaluated using fivefold, tenfold, and 15-fold cross-validation (CV).