Abstract

Background

The demand for orthodontic treatment using clear aligners has been gradually increasing because of their superior esthetics compared with conventional fixed orthodontic therapy. This study aimed to evaluate and compare the compressive strength of three-dimensional direct printing aligners (3DPA) with that of conventional thermo-forming aligners (TFA) to determine their clinical applicability. In the experimental group, the 3DPA material TC-85 (TC-85 full) was used to create angular protrusions called rectangular pressure areas (RPA). A protrusion akin to the power ridge typically employed in conventional TFAs was created using glycol-modified polyethylene terephthalate (PETG; Control 1). RPA was created using the same TC-85 without filling the protrusions (TC-85 blank; Control 2). Compression cycle tests were conducted on an LTM 3 h electrodynamic testing machine (Zwick Roell, Germany), with 500 cycles and compression depths of 100, 300, 500, and 700 µm. Twenty specimens were tested for PETG, 17 for the TC-85 blank, and 19 for the TC-85 full.

Results

Changes in the compressive force were assessed based on the material and thickness. The results indicated significantly higher and broader ranges of compressive strength for specimens fabricated with the 3DPA material TC-85 compared with those fabricated using PETG. Among the TC-85 specimens, TC-85 full demonstrated the highest statistically significant compressive strength .

Conclusions

3DPA technology enables precise modifications in the shape and inner thickness at specific dental sites, including the creation of ridges in targeted areas, of aligners. These alterations enhance the biomechanical capability of aligners to exert selective forces necessary for desired tooth movement while reducing the number of attachments, thereby demonstrating the clinical potential of 3D-printed aligners in orthodontic treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

With the increasing general interest in appearance, the demand for treatments using clear aligners has been gradually increasing to meet the esthetic needs of patients1. Unlike fixed appliances, clear aligners do not require the attachment of brackets to the teeth and offer greater esthetic advantages owing to their transparent material composition. Although high patient compliance for continuous force exertion on the teeth, combined with the practitioner’s biomechanical knowledge is critical, clear aligners can function effectively as esthetic devices in orthodontics with the formulation of a well-designed treatment plan and proper adherence to the practitioner’s instructions2,3.

In orthodontic treatment using clear aligners, the presence of attachments is a critical factor for the efficient correction of rotated and displaced teeth4,5. However, attachments tend to detach easily and compromise the esthetics6. Therefore, bonding methods and techniques should be improved to ensure more effective attachment adhesion and develop attachment designs that facilitate efficient tooth movement.

Meanwhile, instead of using attachments bonded directly to the teeth, altering the design of clear aligners can enable effective tooth movement and efficient orthodontic treatment. Practically, clear aligners, such as Invisalign® (Align Technology, Tempe, USA), utilize modified designs such as the Power Ridge for the correction of displaced teeth. McKay et al.7 demonstrated that the creation of Pressure Columns enables effective tooth movement in an in vitro study, which compared and analyzed the mechanical properties of three-dimensional direct-printing aligners (3DPA) with those of traditional thermoforming aligners (TFA). The 3DPA has the significant advantage of starting with a thinner pressure area in the initial stages of treatment and gradually increasing the thickness, thereby approximating the optimized force required for tooth movement.

This study aimed to test whether specific design features of the 3DPA, such as the rectangular pressure area (RPA) and customized pressure region (CPR), function at a clinically significant level for correcting malposed teeth. The research involved the use of relevant measurement tools and programs to study the material properties. The RPA is a non-customized ridge area on the clear aligner intended to promote tooth movement, similar in concept to Invisalign®’s Power Ridge. In contrast, the CPR is an improved version of the RPA, defined as the ridge area on a clear aligner customized to correspond to the individual shape of each tooth for facilitating more efficient tooth movement. A recent study8 investigated the changes in the force applied to teeth and rotational inertia by varying the outer thickness, but not the inner thickness, of clear aligners. A previous study compared the effects of a power ridge and attachments using the finite element method for lingual root torque9; however, it did not involve 3D printing with shape memory material.

Therefore, the present study aimed to investigate the changes in the mechanical properties of shape memory 3DPA by applying repeated pressure while varying the inner thickness in specific areas where force is assumed to be applied, and explore the clinical applicability of these findings. Our study aimed to experimentally compare the mechanical properties of the 3DPA material, TC-85 (Graphy, Seoul, Korea), and the TFA material, glycol-modified polyethylene terephthalate (PETG), by repeatedly measuring their characteristics under different compression stresses in vitro, which will help identify the differences between these materials. Our research will serve as a starting point for the future design of customized inner surfaces of clear aligners and more efficient and effective orthodontic treatments. The null hypothesis of the study was “there is no difference in the compressive force due to the difference in material and thickness for each specimen.”

Methods

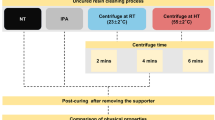

The specimens used in this experiment were made of PETG and a 3D direct-printing photocurable resin. The PETG specimens were prepared using 3 A MEDES Co.‘s 3 A GS030 (Thickness: 0.75 mm, Korea). Orthodontic aligners were directly printed with a 3D printer using TC-85 DAC (Graphy Inc., Korea). The manufacturing process for each specimen was as follows. For the PETG specimens, a PETG sheet was placed on MINISTAR S (SCHEU-DENTAL, Iserlohn, Germany) and heated for 30 s, with the maximum surface temperature of the PETG sheet maintained below 60 °C. A vacuum pressure of 3.7 bar was applied to the prepared model, followed by cooling for 1 min. After trimming the edges of the model, the specimens were trimmed to the appropriate size for each sample. For the 3D direct-printed clear aligner specimens, a TC-85 DAC was used with an LCD-type 3D printer Slash2 4 K (Uniz Inc., China) to print the experimental specimens directly. Post-curing was performed using THC (Graphy Inc., Korea) under nitrogen for 20 min with a total energy exposure of 480 J at an ultraviolet wavelength of 405 nm. Assuming a situation in which compressive force is transmitted to specific areas of the teeth, the experimental group used TC-85, which was fabricated in the form of a rectangular protrusion termed RPA, with a thickness of 1 mm (Fig. 1 right panel, TC-85 full). This is not a strictly customized form that follows the curvature of individual teeth in the strict sense of CPR. For a comparative study of mechanical properties, rectangular protrusions similar to the commonly used power ridges in traditional clear aligners were fabricated using different materials. The experimental and control group 2 (Fig. 1, left panel) used TC-85 and were shaped into rectangular protrusions. Control group 1 used PETG. The models with RPA were printed with a 3D printer. Then, using a vacuum form with a PETG sheet, a thermoformed sheet was created which was cut to 7 × 8 mm rectangular specimen for the cyclic compression test. (Fig. 1, right panel). The experimental and control group 2 used the same material and shape; however, the experimental group had filled embossed areas, whereas Control Group 2 did not. Because TC-85 (experimental group and control group 2) is a 3D printing material, it can be printed with inclined surfaces, allowing selective pressure application to specific areas in a clinical setting. A compression-cycle experiment was conducted using an LTM 3 h electrodynamic testing machine (Zwick Roell, Germany). The crosshead speed of the cycle-testing equipment was fixed at 1 mm/s.

In this study, the number of specimens10 and compression cycles11 were determined based on the results of previous studies. First, the number of specimens was referenced from a previous study that investigated the thermo-mechanical properties of the same material used in this study10. That study used approximately 3 to 6 specimens, providing reasonable evidence within a 10% margin of error. In this study, employing 3–5 specimens per group and depth combination was deemed suitable to minimize the risk of errors in mechanical properties that might occur with the use of a single specimen, while also avoiding unnecessary duplication of specimens. The average values of these specimens were used, and there was no statistical significance in the variation between specimens.

Regarding the number of compression cycles based on depth, a previous in vitro study examining the impact of thermocycling on clear aligners made from polyurethane recommended 600 cycles, equivalent to 20 cycles per day over a period of 30 days, to adequately simulate daily usage in the oral environment11. Although 3D-printed aligners, when produced in-house, can be replaced within days, adjustments to the setup or orders from external manufacturers may extend the replacement time to 3–4 weeks. Given that an aligner might remain in use for this duration, conducting 500 cycles was considered clinically reasonable to mirror the typical usage period.

Additionally, to estimate the necessary sample size of the specimens for this study, a power analysis was performed using G*Power 3.1.9.4. Given the need for comparisons between different groups, ANOVA was selected from the F-tests category. The analysis indicated that a minimum of 42 samples (14 per group) would suffice to detect statistical significance at a p-value of < 0.05 and a confidence level of 80%. To accommodate potential drop-outs due to compression pressure, an additional 20% of samples were included, resulting in a final recommendation of at least 17 samples per group.

Additionally, the study began with 20 specimens per group to account for any specimens that could not be mounted on the electrodynamic testing machine due to volume defects.

The compression depths were set at 100, 300, 500, and 700 µm, respectively. The greatest advantage of DPA is the ability to start with a low thickness variation and gradually increase to a higher thickness variation, so four different thicknesses were selected. Considering in-house 3D printing, the resolution of 3D printers is generally around 100 µm, so the specimen thickness was increased in increments of 200 µm, starting at 100 µm. The average thickness of human PDL is approximately 150–380 µm12. To prevent necrosis due to exceeding the biological limit of compressing the PDL thickness by more than twice in one step, the thickest specimen was designed at 700 µm.

For the PETG group (Control group 1), five specimens were used for a compression depth of 100 µm, and five specimens each for 300, 500, and 700 µm, totaling 20 specimens for the experiment. For the TC-85 blank group (Control group 2), three specimens were used for a compression depth of 100 µm, four specimens for 300 µm, and five specimens each for 500 and 700 µm, totaling 17 specimens for the experiment. As predicted, it was observed that the greatest volume defects occurred in the small, hollow protruding specimens. In the TC-85 full group (experimental group), five specimens were used for a compression depth of 100 µm, four specimens for 300 µm, and five specimens each for 500 and 700 µm, totaling 19 specimens for the experiment. To evaluate the consistency in specimen thickness, measurements were conducted for each specimen using a digital caliper (GAU-178.00, Eurotool, Inc., USA), following the methods described in a previous study that used the same materials10.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis of the experimental data was performed using the SPSS software (IBM SPSS Statistics Version 25.0). Because all the linear data exhibited non-normality, the Kruskal–Wallis test was conducted, followed by post-hoc testing using the Bonferroni correction.

Results

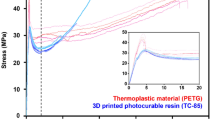

As shown in Table 1; Fig. 2 (a), when pressure is applied with a compression depth of 100 µm (0.1 mm), the compressive force measured for the PETG specimens is approximately 16 N. When applying pressure with a compression depth of 300 µm, the compressive force measured is approximately 50 N, followed by force decay, resulting in a relatively consistent compressive force of approximately 47 N. At a compression depth of 500 µm, the compressive force measured is approximately 90 N, and after repeated cycles, force decay occurs, leading to a relatively consistent compressive force of approximately 80 N. At a compression depth of 700 µm, the compressive force measured is 130 N, and after repeated cycles, force decay occurs, resulting in a relatively consistent compressive force of approximately 115 N.

As shown in Table 1; Fig. 2 (b), when pressure is applied with a compression depth of 100 µm, the compressive force measured for the TC-85 blank specimens is approximately 20 N. When applying pressure with a compression depth of 300 µm, the compressive force measured is approximately 300 N, followed by force decay, resulting in a relatively consistent compressive force of approximately 205 N. At a compression depth of 500 µm, the compressive force measured is approximately 450 N, and after repeated cycles, force decay occurs, leading to a relatively consistent compressive force of approximately 310 N. At a compression depth of 700 µm, the compressive force measured is approximately 485 N, and after repeated cycles, force decay occurs, resulting in a relatively consistent compressive force of approximately 325 N.

As shown in Table 1; Fig. 2 (c), when applying pressure with a compression depth of 100 µm, the compressive force measured for the TC-85 full specimens is approximately 28 N (2.8 kg). When applying pressure with a compression depth of 300 µm, the compressive force measured is approximately 320 N (32 kg), followed by force decay, resulting in a relatively consistent compressive force of approximately 240 N. At a compression depth of 500 µm, the compressive force measured is approximately 520 N (52 kg), and after repeated cycles, force decay occurs, leading to a relatively consistent compressive force of approximately 390 N. At a compression depth of 700 µm, the compressive force measured is approximately 625 N (62.5 kg), and after repeated cycles, force decay occurs, resulting in a relatively consistent compressive force of approximately 455 N.

As shown in Fig. 3 (a), when compressed to a depth of 100 µm, the compressive forces of the three specimens over the cycles were as follows: the PETG specimens exhibited a compressive force of approximately 15 N. The TC-85 blank specimen initially exhibited a compressive force of less than 25 N, which decreased to less than 20 N as the number of cycles increased. The TC-85 full specimens exhibited an initial compressive force of approximately 30 N and experienced force decay.

As shown in Fig. 3 (b), when compressed to a depth of 300 µm, the compressive forces of the three specimens over the cycles were as follows: the PETG specimens exhibited a compressive force of approximately 50 N. The TC-85 blank specimen initially exhibited a compressive force of more than 300 N, which decreased to approximately 200 N as the number of cycles increased. The TC-85 full specimens demonstrated an initial compressive force of more than 300 N, which decayed to less than 250 N.

As shown in Fig. 3 (c), when compressed to a depth of 500 µm, the compressive forces of the three specimens over the cycles were as follows: the PETG specimens exhibited a compressive force of less than 100 N. The TC-85 blank specimen initially exhibited a compressive force of approximately 400 N, which decreased to approximately 310 N as the number of cycles increased. The TC-85 full specimens exhibited an initial compressive force of approximately 400–500 N and experienced force decay.

As shown in Fig. 3 (d), when compressed to a depth of 700 µm, the compressive forces of the three specimens over the cycles were as follows: the PETG specimens exhibited a compressive force of more than 100 N. The TC-85 blank specimen initially exhibited a compressive force of less than 500 N, which decreased to more than 300 N as the number of cycles increased. The TC-85 full specimens showed an initial compressive force of more than 600 N, which decayed to more than 450 N.

Discussion

In this study, the differences in materials and thicknesses were determined, and the changes in compressive force over the cycles were measured. Based on the statistical analysis results and the graphs in Figs. 2 and 3, the null hypothesis of the study, “there is no difference in the compressive force due to the difference in material and thickness for each specimen,” was rejected. When comparing the results on the graph, TC-85 blank and TC-85 full showed relatively smaller differences than PETG, implying that the effect of the difference in the material was greater than the difference in thickness. When measuring compressive force with varying thicknesses of the same material (TC-85), the significant change in compressive force observed at 300 µm suggests that a thickness of 0.3 mm should be considered when designing the inner surface. However, applying a strictly customized CPR design that follows the curvature of specific teeth in a clinical setting may yield different results. The experimental results revealed that, compared to the TFA PETG specimens (Control group 1), the 3DPA TC-85 specimens (Experimental group and Control group 2) exhibited a wide range of compressive strength differences owing to the material thickness and higher compressive endurance. By utilizing a broad spectrum of compressive strengths, TC-85 demonstrated superior applicability for clinical purposes by allowing the design of devices with varying inner thicknesses for application to individual teeth (Fig. 2). When the thickness of the TC-85 specimens was varied, similar results were observed for both the specimens with unfilled embossed areas (TC-85 blank; Control group 2) and those with filled embossed areas (TC-85 full; Experimental group). Planned tooth movement requires customized changes in the thickness of the embossed areas within the device itself, and the experimental results suggest that 3DPA can facilitate this.

The fact that the 3DPA material (TC-85) exhibited better mechanical properties than the TFA material (PETG) under compressive force indicates that the 3DPA material has a high potential to maintain consistent mechanical properties, such as masticatory pressure, under compression. This finding suggests that the 3DPA can withstand a wide range of variations in the oral environment (stability). Additionally, the TC-85 full specimens demonstrated the highest values within the clinical masticatory pressure range of 500–600 N, indicating that the force transmitted through biting can be applied for posterior intrusion. This would be beneficial in cases involving an anterior open bite due to posterior extrusion, as it can be favorably applied to the formation of posterior bite blocks for posterior intrusion. Furthermore, appropriately designing the 3DPA as a retainer could help maintain an occlusion established through treatment for an extended period and prevent relapse of the open bite. Suggesting the application of CPR modeling for the treatment of an anterior open bite, Fig. 4 shows how the posterior bite block can be formed using a 3D modeling program (Materialize Magics 25.01). The areas requiring the posterior bite block (indicated in light green) were selected and given a negative offset of 500 µm. As shown in the orange-marked area on the left, a posterior bite block of 500 µm could be formed on the inner surface of the clear aligner.

According to Lee et al.10, 3DPA exhibits weaker and more flexible characteristics in terms of tensile strength than TFA. This, combined with our experimental results showing that the 3DPA exhibited stronger mechanical properties under compressive force, suggests that specific areas of the clear aligner designed to induce tooth movement can be made strong and rigid, whereas the overall strength of the clear aligner, besides these specific areas, can be made flexible and soft to promote physiological tooth movement. However, as the specimen thickness increases, rigidity also increases, which could lead to patient discomfort and excessive force on the teeth. Clinicians should carefully select a customized and optimized thickness based on tooth movement speed, mobility, and safety.

The pressure measured in the specimens represents the force exerted by the teeth on the clear aligner when the device is worn and, conversely, the reaction force with which the clear aligner presses back on the teeth, transferring pressure to the periodontal ligament. In clinical situations where no additional strong external forces, such as occlusal forces, are applied, the actual force delivered to the teeth is expected to be lower than the experimental values presented. In addition to the direct occlusal force shown in Fig. 4, which is transmitted as a compressive force to the teeth, the compressive force applied to the buccal and lingual surfaces should also be considered. The compressive force exerted on the clear aligner corresponded to the reaction force as the teeth moved to their planned positions in the setup. Although the direct measurement of this force is challenging, the use of materials with mechanical properties capable of accommodating a broad range of compressive forces is expected to facilitate efficient tooth movement in various clinical scenarios. Because this study was not conducted in vivo with actual teeth and oral environments, the results cannot be directly correlated with real clinical situations. Further studies are warranted to determine the ideal form and thickness of clear aligners for achieving planned tooth movements, such as tooth inclination and bodily movement, as intended by the practitioner. This study investigated the mechanical properties of two dental materials (PETG and TC-85) used in clear aligners. Future research should focus on the forces measured on teeth during tooth movement with clear aligners (in vivo), according to the different patterns of tooth movement. The shape of the teeth varies widely, and malformed teeth deviate from typical forms. For instance, the diminutive shape of the maxillary lateral incisors is known to occur in approximately 1.8% of the population13. The presence of attachments or ridged areas on the appliance is essential14. The results of this study suggest that the 3DPA can be custom-designed for the efficient movement of individual teeth. Unlike TFA, 3DPA allows for the design of appliances that meet the practitioner’s plan (comparison of PETG and TC-85 full). In typical thermoforming, a printed model shaped according to the desired tooth movement is required, and a clear aligner is produced by thermoforming a transparent sheet over this model15. Therefore, the shapes and sizes of the inner surfaces of the aligners are limited. In contrast, the 3D direct printing method has no such limitations, making it more advantageous16,17. Therefore, the advantages of the direct printing method in producing customized clear aligners for efficient movement of each tooth18 are expected to be significant. In the future, the primary tasks of orthodontists will likely involve developing and selecting optimized designs that are more effective for desired tooth movements, such as tooth rotation, tipping, and bodily movement, while considering the shape of the teeth. Additionally, considering the results of this study, changes in the inner surface design (RPA and CPR) are expected to function effectively without using the attachments for posterior intrusion or anterior rotation and torque control. This can possibly reduce the number of attachments required adopting CPR (Fig. 5). However, this hypothesis requires in vivo validation in follow-up studies to confirm its practical application and effectiveness in orthodontic treatment.

In addition to not being an in vivo experiment, another limitation of this study was that the specimen shapes were standardized for quantitative comparison, indicating that strictly defined CPR specimens were not created. Clear aligner designs were not modified to match the unique shapes of individual teeth. However, by varying the thickness of the RPA (comparison of the TC-85 blank and TC-85 full), the potential superiority of the CPR was identified. The solid specimens (TC-85 full) exhibited a wide range of compressive and maximum strengths, suggesting that customized CPR-shaped designs tailored to the unique shapes of individual teeth could exert optimized forces on each tooth. Further in vivo research is essential to explore the impact of factors such as the intraoral environment, cyclic loading in various orientations, and patient-specific variability. Future studies should incorporate clinical trials to validate the compressive strength benefits of 3DPA materials under realistic conditions, taking into account the variability in tooth morphology and the complexity of treatment.

Conclusions

-

1.

3DPA allows for the adjustment of the device’s shape and inner thickness corresponding to specific teeth according to the practitioner’s plan for the planned movement of certain teeth, and it can create ridged areas (RPA and CPR) on specific parts.

-

2.

Compressive strength measurements of the three specimens (PETG, TC-85 blank, and TC-85 full) based on thickness indicated that TC-85 full exhibited the broadest range and highest compressive strength, suggesting the highest potential for application in various clinical situations.

-

3.

Changes in the inner thickness of the device and the creation of ridged areas can apply a selective force for the targeted tooth surface.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- 3DPA:

-

Three-dimensional direct printing aligners

- TFA:

-

Thermo-forming aligners

- RPA:

-

Rectangular pressure areas

- PETG:

-

Glycol-modified polyethylene terephthalate

- CPR:

-

Customized pressure region

References

Livas, C., Delli, K., Lee, S. J. & Pandis, N. Public interest in Invisalign in developed and developing countries: a Google trends analysis. J. Orthod. 50, 188–195. https://doi.org/10.1177/14653125221134304 (2023).

Kanpittaya, P. et al. Clear aligner: effectiveness, limitations and considerations. J. Dent. Assoc. Thai. 71, 231–236. https://doi.org/10.14456/jdat.2021.25 (2021).

AlMogbel, A. Clear Aligner Therapy: up to date review article. J. Orthod. Sci. 12, 37. https://doi.org/10.4103/jos.jos_30_23 (2023).

Simon, M., Keilig, L., Schwarze, J., Jung, B. A. & Bourauel, C. Treatment outcome and efficacy of an aligner technique–regarding incisor torque, premolar derotation and molar distalization. BMC Oral Health. 14, 68. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6831-14-68 (2014).

Gomez, J. P., Peña, F. M., Martínez, V., Giraldo, D. C. & Cardona, C. I. initial force systems during bodily tooth movement with plastic aligners and composite attachments: a three-dimensional finite element analysis. Angle Orthod. 85, 454–460. https://doi.org/10.2319/050714-330.1 (2015).

Thai, J. K., Araujo, E., McCray, J., Schneider, P. P. & Kim, K. B. Esthetic perception of clear aligner therapy attachments using eye-tracking technology. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 158, 400–409. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajodo.2019.09.014 (2020).

McKay, A. et al. Forces and moments generated during extrusion of a maxillary central incisor with clear aligners: an in vitro study. BMC Oral Health. 23, 495. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-023-03136-2 (2023).

Grant, J. et al. Forces and moments generated by 3D direct printed clear aligners of varying labial and lingual thicknesses during lingual movement of maxillary central incisor: an in vitro study. Prog Orthod. 24, 23. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40510-023-00475-2 (2023).

Hong, Y. Y., Kang, T., Zhou, M. Q., Zhong, J. Y. & Chen, X. P. Effect of varying auxiliaries on maxillary incisor torque control with clear aligners: a finite element analysis. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 166, 50–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajodo.2024.02.012 (2024).

Lee, S. Y. et al. Thermo-mechanical properties of 3D printed photocurable shape memory resin for clear aligners. Sci. Rep. 12, 6246. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-09831-4 (2022).

Cintora-López, P. et al. In vitro analysis of the influence of the thermocycling and the applied force on orthodontic clear aligners. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 11, 1321495 (2023).

Nanci, A. & Bosshardt, D. D. Structure of periodontal tissues in health and disease. Periodontol 2000. 40, 11 (2006).

Hua, F., He, H., Ngan, P. & Bouzid, W. Prevalence of peg-shaped maxillary permanent lateral incisors: a meta-analysis. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 144, 97–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajodo.2013.02.025 (2013).

Murphy, S. J. et al. Comparison of maxillary anterior tooth movement between Invisalign and fixed appliances. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 164, 24–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajodo.2022.10.024 (2023).

Bichu, Y. M. et al. Advances in orthodontic clear aligner materials. Bioact Mater. 22, 384–403. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bioactmat.2022.10.006 (2023).

Jindal, P., Juneja, M., Siena, F. L., Bajaj, D. & Breedon, P. Mechanical and geometric properties of thermoformed and 3D printed clear dental aligners. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 156, 694–701. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajodo.2019.05.012 (2019).

Cole, D., Bencharit, S., Carrico, C. K., Arias, A. & Tüfekçi, E. Evaluation of fit for 3D-printed retainers compared with thermoform retainers. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 155, 592–599. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajodo.2018.09.011 (2019).

Charalampakis, O., Iliadi, A., Ueno, H., Oliver, D. R. & Kim, K. B. Accuracy of clear aligners: a retrospective study of patients who needed refinement. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 154, 47–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajodo.2017.11.028 (2018).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Editage (http://www.editage.co.kr) for English language editing.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

BGB and YHK wrote the main manuscript text, and GHL performed the 3D lab work. JL and JM conducted the experiments. HK and JWS contributed to the research design and conceptualization. HSC organized the manuscript collectively.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All human research procedures were followed in accordance with the ethical standards of the committee responsible for human experimentation (institutional and national), and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2013. This study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Ajou University Hospital (IRB No: AJOUIRB-EX-2024-280).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bae, B.G., Kim, Y.H., Lee, G.H. et al. A study on the compressive strength of three-dimensional direct printing aligner material for specific designing of clear aligners. Sci Rep 15, 2489 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86687-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86687-4

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Mechanical properties of thermoformed and direct-printed aligner materials after immersion in 37 °C water: a 14-day in vitro study

Scientific Reports (2026)

-

Evaluation of color stability and material surface stability of different types of clear aligners under curcumin staining in vitro

BMC Oral Health (2025)