Abstract

The composition and pattern of ecosystems play a crucial role in determining the overall condition and spatial variations of ecosystem services. In this study, we explored the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI), six land use/land cover change (LULC) types, and their landscape patterns to reflect spatial-temporal dynamics from 2010 to 2020 in the upper and middle reaches of the Fenhe River Basin. The trend analysis of Mann-Kendall tests was used to assess the NDVI variation of each pixel over the past decade. Shannon’s Diversity Index (SHDI) was used to quantify the complexity of the landscape pattern of local LULC. Meanwhile, the spatial-temporal dynamic variations of vegetation NDVI and six LULC types were illustrated using geographic mapping methods. The results were presented as follows: (1) From 2010 to 2020, vegetation cover increased, with an annual NDVI increment of 0.003 (P < 0.001). Spatially, there was a significant increasing trend in NDVI, particularly in high-altitude mountainous areas where the vegetation cover mostly consisted of forests or grasslands. However, there was no significant change in vegetation cover in the low-lying urban agglomeration area. (2) During the period from 2010 to 2020, there was a significant decrease in the area of water bodies and wetlands, the rate of decrease slowed from 2015 to 2020. Specifically, the percentage of decrease from 2010 to 2015 increased by more than 14%. This proportion exceeded 30% when compared to the final governmental ecological management goal set during the 13th Five-Year Plan Period (2016–2020). (3) During the same period, the SHDI of LULC exhibited heterogeneous characteristics. In the high-altitude areas near the river basin boundary, SHDI values were below 1.0. Conversely, in the low-altitude plains and urban areas with frequent human activities, SHDI values exceeded 1.0, reaching above 1.5 in urban areas. This study provides a scientific reference for the construction and management of the ecological environment in the Fenhe River Basin, along with practice insights for ecological protection and high-quality development in the Yellow River Basin.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The dynamics of ecosystem spatial patterns are closely linked to land use and land cover (LULC)1,2,3. LULC patterns represent the spatial arrangement and combination of different types, highlighting their heterogeneity4,5,6. Reasonable changes in LULC can have positive effects on the ecological environment, while excessive development can lead to issues such as desertification, vegetation degradation, and reduced water areas7,8,9. The analysis of landscape patterns primarily focuses on landscape heterogeneity and dynamics, with landscape pattern indices providing a quantitative description of changes in these patterns10,11,12,13. Studying changes in LULC within a basin is crucial for understanding shifts in the ecological environment. Previous studies have primarily utilized remote sensing to investigate changes in the spatial distribution of land use6,14,15,16, assess the impact of these changes on ecosystem services17,18,19,20, simulate scenarios of land use changes21,22,23,24, and evaluate their potential effects on ecosystems25,26,27.

In recent years, scholars have increasingly expressed concern about the impact of ecological policies and projects on the environment. Wang et al. revealed that urban and rural construction land undergoes the most significant annual changes in the middle and lower reaches of the Yellow River Basin, identifying population and GDP as the main driving factors28. Pan et al. indicated a negative correlation between the expansion of built-up land and changes in ecological quality in Quanzhou city, southeast China, from 1989 to 2018. They found that government policies significantly influenced land use changes, urbanization, and eco-environmental changes29. However, Xiong et al. discovered that climate change, ecological restoration measures, urbanization, and reservoir impoundment did not significantly alter the spatial distribution patterns of land use or the climate driving mechanisms of vegetation growth in the Three Gorges Reservoir intervening basin30. Bufebo and Elias identified agricultural expansion, policy changes, social unrest, population pressure, land shortage, and biophysical factors as the major driving forces behind the LULC changes in the Shenkolla watershed in south-central Ethiopia31. While previous studies have mainly focused on the evolution of river basins, comprehensive research on the overall ecological quality characteristics and changes within river basins is lacking. Additionally, there is a need for more quantitative research on how to implement differentiated land and ecological protection policies based on regional characteristics.

In this study, we focus on the upper and middle reaches of the Fenhe River Basin and examine the dynamic characteristics of the ecological system pattern from 2010 to 2020 using remote sensing data. The objectives of this study are (1) to identify the spatial-temporal trends and strength of basin vegetation over the last decade; (2) to assess the spatial-temporal complexity of the landscape pattern of LULC in the Fenhe River Basin, providing a scientific basis for planning, constructing, and managing ecological governance and restoration projects; and (3) to display the spatial-temporal dynamics of both vegetation and LULC during the last decade. This research could provide deep insights for local ecological protection and high-quality development practices in the Yellow River Basin.

Materials and methods

Description of study area

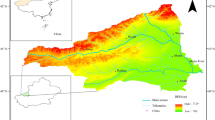

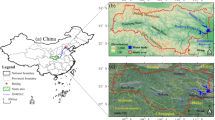

The Fenhe River Basin, know as the “mother river” of Shanxi Province, is located in the central part of the region (35°-39°N,110°-113°E). It serves as an important ecological functional area, a densely populated region, a significant grain and cotton production zone, and an economically developed area. As part of the national strategy for ecological protection and high-quality development of the Yellow River Basin, the Fenhe River plays a crucial role as the second largest tributary of the Yellow River32,33,34. The terrain of the basin generally slopes from the river valley to the east and west, with elevation increasing from south to north. The land cover in the basin is diverse, primarily comprising cultivated land in the Fenhe River valley, as well as grasslands, forests, and shrublands in the mountains and hills on both sides of the basin. The urban built-up area also occupies a significant portion, primarily distributed along the riverbanks35.

The Fenhe River Basin experiences a typical temperate continental semi-arid monsoon climate, characterized by four distinct seasons. The average annual temperature ranges from 6 to 13 °C, while the average annual rainfall varies from 400 to 700 mm. The rainy season accounts for 78.8% of the total annual precipitation. In this study, we focus on the upper and middle reaches of the river, extending from its source in Ningwu to the Wangzhuang section in Lingshi county. The basin covers an area of 26,210 km2, which accounts for 25.5% of the total provincial area (Fig. 1). Spatial shapefiles of the Fenhe watershed boundary can be freely obtained from Natural Earth, which is within the public domain or available under open access licenses36.

Research methods

Data sources

The Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) is used to analyze changes in vegetation within the basin. The NDVI remote sensing data is derived from NASA MODIS data (MOD13A3), with a monthly scale and a spatial resolution of 1 km. This dataset covers the period from 2010 to 2020, totaling 132 datasets.

To evaluate land cover and land use changes in the basin, LULC remote sensing data from the years 2010, 2015, and 2020 is used. This data is sourced from the Global Land Cover Types dataset published by the Remote Sensing Center of Tsinghua University37.

The LULC data is a fine-resolution (500 m) product that enables dynamic monitoring of global surface land cover from 2001 to 2020 (https://lpdaac.usgs.gov/products/mcd12q1v006/). This dataset was produced using all available Landsat data from the same period, with annual updates. The overall classification accuracy and Kappa coefficient exceed 91% and 0.8738, respectively, indicating the effectiveness of the LULC classification in this study. The spatial resampling resolution of the data is 1 km, which has been widely used to reflect vegetation dynamics39,40. Given that the basin covers an area of 26,210 km2, the 1 km spatial resolution adequately represents vegetation dynamics. Land use types are classified into six categories after spatial resampling and reclassification: Cultivated Land, Forest, Grass Land, Artificial Surfaces, Useless Land, and Water Wetland.

We creat the map using the “sf” package in R (version 4.2.0, https://cran.r-project.org), and the shapefiles utilized for the map are sourced from the Map Technology Review Center of the Ministry of Natural Resources of China. The National Standard Map Service System, which was launched in October 2016, is openly accessible at http://bzdt.ch.mnr.gov.cn/. All map data can be accessed freely.

Time trend analysis methods

The trend analysis employed the non-parametric Mann-Kendall and Theil-Sen’s slope methods. The Mann-Kendall trend test is a non-parametric approach that does not require the data to follow a specific distribution, such as a Gaussian distribution, and it can also handle missing data. This method is widely used and practical for trend analysis. Theil-Sen’s slope is used to calculate the slope of the trend and can be effectively combined with the Mann–Kendall test. This combination has incerasingly been adopted for analyzing long time series of vegetation, reflecting the variations in trends for each pixel over time41. The Theil–Sen Median slope test calculates the median slopes from all n(n − 1)/2 pair-wise combinations of the time series data, representing the increase or decrease in NDVI on a pixel scale over the 11-year period from 2010 to 2020.

where, βNDVI represents the Theil–Sen median, and NDVIi and NDVIj represent the NDVI values for years i and j. If βNDVI > 0, it indicates a rising trend in the NDVI. Conversely, if βNDVI < 0, it suggests a decreasing trend in the NDVI.

The Mann–Kendall test calculates the significance of a trend using the following formula. It is assumed that the time sereies data consists {NDVIi}, where i = 2010, 2001, …, 2020.

The statistics of Z is defined as:

where NDVIi and NDVIj represent the NDVI values of pixels i and j; n is the length of the time series; sgn is a sign function; and the Z statistic is valued in the range of (−∞, +∞); s(S) is the variance and S is the Kendall sum statistic. A given significance level, |Z| > u0.025=1.96, signifies that the time series shows significant variations at a statisticcal confidence level of 0.05.

Landscape index analysis

The Shannon’s Diversity Index (SHDI) was used to measure landscape heterogeneity42. SHDI quantifies the complexity of landscape patterns, also referred to as pattern diversity. It emphasizes the significance of rare patch types in providing valuable information. SHDI is an effective indicator for comparing and analyzing changes in diversity and heterogeneity across different landscapes or within the same landscape over time43,44. The formula for calculation is as follows.

where Pi is the proportion of class i and m is the number of classes. The SHDI value is always larger than zero.

In our LULC analysis, we used remote sensing data with a spatial resolution of 0.5 km to capture the landscape pattern. SHDI is a widely used metric in biodiversity and ecology that considers both the number of classes and the abundance of each class. The SHDI ranges from zero to higher values, with SHDI equal to zero when only one patch is present. As the number of classes increases, SHDI value rises without limit, particularly when the proportions are evenly distributed. For each 500 m spatial resolution pixel in the study area, we calculated the SHDI and displayed these dynamics spatially and temporally. We believe that higher SHDI values indicates less interference from human activities. The six land cover types effectively reflect the changes in “natural” land cover. By comparing different years, we were able to identify the dynamic characteristics of LULC.

Spatial statistical methods

Spatial data was analyzed using ArcGIS 10.4 software and the R programming language for trend analysis and spatial overlay analysis. Trend analysis employed the M-K Kendall statistical method with a significance level of 0.05, which involved calculating statistical change slopes, assessing change significance, and mapping their spatial distribution. Land use transition analysis was performed using ArcGIS to develop land use transition matrices. The landscape index of SHDI was analyzed using the R package “landscapemetrics.” Data visualization was accomplished with the “tidyverse” packages in R (version 4.2.0, https://cran.r-project.org ).

Results and analysis

Spatial-temporal dynamics of NDVI in the Upper and Middle reaches of the Fenhe River Basin

Vegetation coverage plays a crucial role in regional environmental change and monitoring studies45,46. A widely used and practical method for measuring vegetation coverage is the NDVI. Figure 2 illustrates the remote sensing data interpretation used to estimate vegetation coverage. Regions with NDVI ≤ 0 represent non-vegetated areas, while areas with NDVI > 0 indicate vegetated regions. Analyzing the spatiotemporal changes in vegetation coverage over the past 11 years (2010–2020), there has been a noticeable increasing trend in average annual NDVI values, particularly in regions indicated by the green portion.

Figure 3 illustrates the monthly spatial variation of NDVI from 2010 to 2020. Generally, NDVI values are higher during the summer months (June to August) and lower during the winter months (December, January, and February).

Figure 4 depicts the shifting NDVI pattern in the study area from 2010 to 2020. The annual trend chart clearly shows a consistent upward linear regression trend, with an annual increase in NDVI of 0.003 (P < 0.001). Analyzing the average monthly NDVI changes over the 11-years period in the upper and middle reaches of the Fenhe River Basin, it is evident that the NDVI peaks in August (0.681) and hits its lowest point in January (0.214).

Figure 5a presents the spatial analysis of multi-year monthly NDVI at each grid points, utilizing the Mann-Kendall trend analysis and Sen’s slope analysis. The NDVI remote sensing data has a spatial resolution of 1 km. The overall trend of NDVI slopes is positive, indicating an increase in NDVI and improved vegetation coverage. However, there are areas with negative slopes, particularly in low-altitude regions experiencing rapid urban development. Figure 5b displays the spatiotemporal distribution of NDVI trends at a 1 km resolution in the upper and middle reaches of the Fenhe River Basin. The significance of NDVI changes is categorized into four classes: extremely significant (P < 0.001), significant (P < 0.05), slight change (P < 0.1), and no significant change (P > 0.1). Spatially, regions with extremely significant and significant changes are primarily found in high-altitude mountainous areas with minimal human disturbance, where vegetation coverage consists mostly forests or grasslands. In contrast, areas with no significant change are mainly concentrated in low-altitude urban zones.

Spatial-temporal dynamics of LULC

Urbanization is the main driving force behind the changes in LULC in this region47. By examining the LULC changes over multiple years and making comparisons, we can better understand how different land types are evolving. One particular concern is the alteration of wetlands or water bodies within the Fenhe River Basin. Figure 6 presents remote sensing data on LULC for the upper and middle reaches of the Fenhe River Basin for the years 2010, 2015, and 2020, which have been categorized into six land types after resampling.

The land use data reveal that forests dominate high-altitude mountainous regions, while cultivated land is more prevalent in low-altitude areas. In 2010, cultivated land and forests accounted for the largest proportions of the total area, approximately 43.0% and 43.2%, respectively. Water bodies or wetlands covered around 4.2% of the area. By 2015, the land use structure still showed that cultivated land and forests as the largest categories, at about 35.1% and 31.3% of the total area, respectively. Grassland incerased significantly, rising from 7.6% in 2010 to 28.7% in 2015. However, water bodies or wetlands experienced a substantial decline, dropping to only 0.7%. By 2020, the land use structure remained similar, with cultivated land and forests continuing to dominate, accounting for approximately 37.7% and 30.2% of the total area, respectively. The proportion of grassland decreased from 28.7% in 2015 to 24.4% in 2020, and the area of water bodies or wetlands further decreased to just 0.3%.

As shown in Fig. 7, from 2010 to 2015, water bodies or wetlands experienced a significant decrease, with the majority being converted to cultivated land (51.3%), and some transformed into artificial surfaces (33.9%). Only a small proportion shifted to grassland or forests (2.2%), while maintaining their original status as water body or wetlands. Similarly, from 2015 to 2020, there was another significant reduction in water bodies or wetlands, primarily converting to cultivated land (44.0%) and artificial surfaces (18.4%). Wetlands or water bodies that remained accounted for 16.3% of land use during this period.

Spatial-temporal change of Landscape spatial structure

Figure 8a illustrates the SHDI of LULC landscapes in the upper and middle reaches of the Fenhe River Basin in 2010, at a spatial resolution of 1 km. In the high-altitude boundary areas of the basin, SHDI values are below 1.0 and approach 0 near the edges. These regions, characterized by relatively low SHDI, are associated with specific land use types. Higher altitude areas exhibit a uniform land use type, resulting in lower SHDI values. Conversely, regions at lower altitudes, such as plains and urban areas with higher human activity, display higher SHDI values, exceeding 1.0, with urban areas reaching over 1.5. This indicates greater landscape diversity in these locations, with no dominant land use type. In 2015, regions with relatively high SHDI began to radiate from urban clusters toward surrounding areas, particularly shifting northward (Fig. 8b). The areas with high SHDI, indicate of significant human activity in urban areas in 2010, generally decreased by 2015, suggesting a gradual homogenization of land use types in urban areas. The northward spatial shift of SHDI indicates that the originally relatively homogeneous land use types in the northern areas diversified between 2010 and 2015. In 2020, compared to 2015, regions with relatively high SHDI tended to cluster in the south (Fig. 8c), suggesting an increase in landscape uniformity. Overall, the spatial distribution of SHDI for LULC landscapes showed higher values in the northern parts and lower values in the southern parts, with significant influences from urbanization and human activities on LULC landscapes.

From 2010 to 2015, regions with higher SHDI scores were primarily located in the northern areas, with a small portion in the far south. This suggests an increase in LULC type diversity in these regions. However, urban areas and the central part of the watershed experienced negative changes in SHDI values (Fig. 9a). In the subsequent period from 2015 to 2020, there was a widespread decrease in LULC landscape diversity throughout almost the entire watershed, as depicted in Fig. 9b. Additionally, the eastern part of the watershed experienced a significant decline in SHDI, indicating a gradual expansion of human activities toward the east. In summary, between 2010 and 2020, the spatial changes in LULC landscape diversity varied (Fig. 9c). Regions that experienced significant reductions in diversity were primarily concentrated in the central and eastern parts of the watershed. These changes were largely driven by urbanization processes radiating outwards from urban centers, resulting in a homogenization of land use types and a decrease in overall diversity.

Discussion

Natural factors play a crucial role in shaping regional ecosystem patterns and have lasting effects on landscape changes. Human activities can drive rapid alterations in these patterns over short periods48,49,50. The study area exhibited a clear increasing trend in NDVI changes from 2010 to 2020. In the high-altitude mountain areas within the basin, there was a notable increase in NDVI, likely due to limited human activity and favorable conditions for afforestation. This resulted in an increase in forest area. In contrast, NDVI remained relatively unchanged in low-altitude urban clusters, which can be attributed to high levels of urbanization and developed agricultural activities that encroached significantly on forest and grassland areas51. This finding is consistent with the Wuliangsu Lake Basin, where a strong correlation was noted between annual NDVI and human activities52. The seasonal trend of vegetation NDVI growth intensity in the Fenhe River Basin over the past 11 years followed the order of summer > autumn > spring > winter, aligning with vegetation phenology. Liu et al.53 indicated that precipitation and groundwater are primary driving forces behind the spatial-temporal variability of vegetation. This may be linked to the national strategic project “Return of Cropland to Forests,” which began in 2002 and has proven to be a significant ecological initiatives with the largest investment, strongest policy support, widest coverage, and highest level of public participation in China and worldwide. The project systematically ceases the cultivation of sloping farmland. Following the principle of suitable land and tree pairings, afforestation is implemented according to local conditions to restore forest vegetation. Project components include converting sloping farmland to forests and afforesting of suitable barren mountains and wastelands. So far, these initiatives have improved degraded vegetation, resulting in a rapid increase in NDVI values. Furthermore, the basin’s favorable water and thermal conditions during summer have facilitated swift vegetation recovery and growth. Conversely, winter exhibited the lowest vegetation survival rates, influencing changes in NDVI. It has also been reported that the average NDVI increased during the growing season (April to September) in the Wei and Jing River Basins54.

The LULC data from 2010 to 2020 revealed important trends in land use, particularly in mountain and low-altitude regions. Forests were found to dominate high-altitude mountain areas, while cropland prevailed in low-altitude regions. The most significant change occurred between 2015 and 2020, when previously unused land was converted into water bodies or wetlands, resulting in a decrease in their extent. This suggests that ecological restoration or construction efforts were successful during this period. Yang et al.55 also demonstrated that in the context of ecological restoration and urban development in the Yellow River Basin, the stabilization of the LULC conversion structure will be a distinguishing characteristic. The amount of cropland transferred out will exceed that of other LULC types, with built-up land, forest, grassland, and water in the Yellow River Basin increasing, while the area of unused land and cropland decreased between 2000 and 202056. These chages may be related to limited precipitation, which has left the region predominantly covered by unused land and grassland. Forests are mainly found in mountainous areas due to the influence of terrain undulation and altitude. These areas often create microclimatic environments distinct from the surrounding dry land regions, providing suitable conditions for forest formation.

In the Fenhe River Basin, since 2015, the ecological environmental protection policies implemented by Shanxi Province, including the “Fen River as the focal point of the ‘seven rivers’ ecological conservation and restoration overall program” and the “Fen River Basin Ecological Restoration Planning (2015–2030)” have led to increased comprehensive regulation and ecological restoration efforts in the basin’s land and space. Consequently, the proportion of water bodies and wetlands has increased. Meanwhile, the maintenance of the original LULC types has risen to 16.33%, compared to 2.2% during the 13th Five-Year Plan period(2016–2020). This indicates a significant improvement in ecological restoration and protection.

The landscape pattern is jointly influenced by multiple factors, including population, economy, soil, hydrology, policy formulation, and technological development, with different landscapes being affected by distinct factors57. From 2010 to 2020, urbanization primarily influenced the SHDI, leading to a more uniform and less diverse land use pattern. This underscores the significant impact of human activities on LULC landscapes. Additionally, there is a trend of expansion towards the eastern region of the study area. The results indicated that landscape patterns can provide an accurate and significant evaluation of ecosystems, helping to identify areas with lower SHDI and degraded lands. Although the ecological protection and restoration project for mountains, forests, fields, lakes, and grasslands, which began in 2018, has not yet fully demonstrated the positive impact of improved ecological land use on the environment, it has provided clear insights into changes in ecological diversity based on this study ‘s findings.

This research could uncover potential mechanisms by which climatic factors, LULC changes, and human regulations influence hydrological ecosystem, thereby providing a scientific basis for ecological management and high-quality development policies in the Yellow River Basin.

Conclusion

From 2010 to 2020, there was an increase in vegetation cover, with an annual NDVI increment of 0.003 (P < 0.001). However, areas of decreased vegetation were primarily observed in low-altitude rapidly urbanizing regions. Notably, the vegetation changes in high-altitude mountain areas were highly significant and statistically significant, with the predominant vegetation cover being forest or grasslands. Conversely, areas with no significant changes were concentrated in low-altitude urban clusters.

During the same period, there was a significant decrease in water body or wetland areas. The conversion of these areas to other land types, particularly cropland and partially construction land, was notable. The proportion of wetlands and water bodies declined throughout the observed period, though the rate of decline slowed somewhat from 2015 to 2020. The conversion of water bodies or wetlands to other land types decreased by over 14% from 2015 to 2020.

Throughout 2010 to 2020, the spatial changes in SHDI exhibited heterogeneous characteristics. Areas with significantly reduced LULC diversity were mainly concentrated in the central part of the basin, where urban clusters and zones of intensive human activity were present. As a result, there was a trend toward uniformity and decreased diversity in land use cover types. These spatial changes in LULC landscapes underscore the significant influence of human activities on land cover patterns. Future research should utilize high-frequency remote sensing data over a long-term period, and the analysis should be extended to encompass the entire watershed.

Data availability

The spatial shape files of the waetershed boundary can be freely obtained in Natural Earth within the public domain or with open access licenses. https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml? persistentId=doi:10.7910/DVN/KBFNSWThe land use and land cover remote sensing data from is sourced from the Global Land Cover Types dataset published by the Remote Sensing Center of Tsinghua University. Example from: doi: 10.1016/j.scib.2019.03.002. The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Winkler, K., Fuchs, R., Rounsevell, M. & Herold, M. Global land use changes are four times greater than previously estimated. Nat. Commun. 12, 2501 (2021).

Jiang, L., Liu, Y., Wu, S. & Yang, C. Analyzing ecological environment change and associated driving factors in China based on NDVI time series data. Ecol. Indic. 129, 107933 (2021).

Xiang, Y., Meng, J., You, N., Chen, P. & Yang, H. Spatio-temporal analysis of anthropogenic disturbances on landscape pattern of tourist destinations: A case study in the Li River Basin, China. Sci. Rep. 9, 19285 (2019).

Duarte, G. T., Santos, P. M., Cornelissen, T. G., Ribeiro, M. C. & Paglia, A. P. The effects of landscape patterns on ecosystem services: Meta-analyses of landscape services. Landsc. Ecol. 33, 1247–1257 (2018).

Joorabian Shooshtari, S., Silva, T., Raheli Namin, B. & Shayesteh, K. Land use and cover change assessment and dynamic spatial modeling in the Ghara-Su Basin, Northeastern Iran. J. Indian Soc. Remote 48, 81–95 (2020).

Guo, L. et al. Revealing the fingerprint of climate change in interannual NDVI variability among biomes in Inner Mongolia, China. Remote Sens-Basel 12, 1332 (2020).

Plakidas, K., Schall, D. & Zdun, U. Evolution of the R software ecosystem: Metrics, relationships, and their impact on qualities. J. Syst. Softw. 132, 119–146 (2020).

Hou, L., Wu, F. & Xie, X. The spatial characteristics and relationships between landscape pattern and ecosystem service value along an urban-rural gradient in Xi’an city. China Ecol. Indic. 108, 105720 (2020).

Statuto, D., Cillis, G. & Picuno, P. GIS-based analysis of temporal evolution of rural landscape: A case study in Southern Italy. Nat. Resour. Res. 28, 61–75 (2019).

Li, B., Liang, Z., Bao, Z., Wang, J. & Hu, Y. Changes in streamflow and sediment for a planned large reservoir in the middle Yellow River. Land. Degrad. Dev. 30, 878–893 (2019).

Li, K. et al. Performance analyses of differential evolution algorithm based on dynamic fitness landscape. Int. J. Cogn. Inf. Na 13, 36–61 (2019).

Seidl, N. P. & Golobic, M. Quantitative assessment of agricultural landscape heterogeneity. Ecol. Indic. 112, 106115 (2020).

Zhang, L., Hou, G. & Li, F. Dynamics of landscape pattern and connectivity of wetlands in western Jilin Province, China. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 22, 2517–2528 (2020).

Baniya, B., Tang, Q., Huang, Z., Sun, S. & Techato, K. Spatial and temporal variation of ndvi in response to climate change and the implication for carbon dynamics in Nepal. Forests 9(6), 329 (2018).

Birhanu, L., Hailu, B. T., Bekele, T. & Demissew, S. Land use/land cover change along elevation and slope gradient in highlands of Ethiopia. Remote Sens. Appl. Soc. Environ. 16, 100260 (2019).

Li, P. et al. Spatio-temporal variation characteristics of NDVI and its response to climate on the Loess Plateau from 1985 to 2015. Catena 203, 105331 (2021).

Tan, J., Yu, D., Li, Q., Tan, X. & Zhou, W. Spatial relationship between land-use/land-cover change and land surface temperature in the Dongting Lake area, China. Sci. Rep. 10, 9245 (2020).

Liu, W. et al. Impacts of urbanization-induced land-use changes on ecosystem services: A case study of the Pearl River Delta Metropolitan Region, China. Ecol. Indic. 98, 228–238 (2019).

Fang, Z. et al. Impacts of land use/land cover changes on ecosystem services in ecologically fragile regions. Sci. Total Environ. 831, 154967 (2022).

Li, Y. et al. The role of land use change in affecting ecosystem services and the ecological security pattern of the Hexi regions, Northwest China. Sci. Total Environ. 855, 158940 (2023).

Kindu, M., Schneider, T., Döllerer, M., Teketay, D. & Knoke, T. Scenario modelling of land use/land cover changes in Munessa-Shashemene landscape of the Ethiopian highlands. Sci. Total Environ. 622, 534–546 (2018).

Chang, X., Zhang, F., Cong, K. & Liu, X. J. Scenario simulation of land use and land cover change in mining area. Sci. Rep. 11, 12910 (2021).

Lou, Y. et al. Multi-scenario simulation of land use changes with ecosystem service value in the Yellow River Basin. Land 11, 992 (2022).

Cao, M. et al. Multi-scenario simulation of land use for sustainable development goals. IEEE J-STARS 15, 2119–2127 (2022).

Wu, D., Zou, C., Cao, W., Xiao, T. & Gong, G. Ecosystem services changes between 2000 and 2015 in the Loess Plateau, China: A response to ecological restoration. PLOS ONE 14, e0209483 (2019).

Wang, F., Yuan, X. Z. & Xie, X. P. Dynamic change of land use/land cover patterns and driving factors of Nansihu Lake Basin in Shandong Province, China. Environ. Earth Sci. 80, 180 (2021).

Phan, D. C. et al. First comprehensive quantification of annual land use/cover from 1990 to 2020 across mainland Vietnam. Sci. Rep. 11, 9979 (2021).

Wang, W. Assessing the sustainability impacts of the xiaolangdi dam: Land use and socioeconomic change in the Middle and Lower reaches of the Yellow River Basin. Sustainability 15, 14343 (2023).

Pan, W., Wang, S., Wang, Y., Yu, Y. & Luo, Y. Dynamical changes of land use/land cover and their impacts on ecological quality during China’s reform periods: A case study of Quanzhou city, China. PLOS ONE 17, e0278667 (2022).

Xiong, Y. et al. Land use pattern and vegetation cover dynamics in the Three Gorges Reservoir (TGR) intervening basin. Water 12, 2036 (2020).

Bufebo, B. & Elias, E. Land use/land cover change and its driving forces in Shenkolla watershed, south Central Ethiopia. Sci. World J. 13, 9470918 (2021).

Zhang, L. et al. Variation in runoff, suspended sediment load, and their inter-relationships in response to climate change and anthropogenic activities over the last 60 years: A case study of the Upper Fenhe River Basin, China. Water 12, 1757 (2020).

Zhao, Y., Dang, J. & Wang, F. Sources of nitrogen pollution in upstream of fenhe river reservoir based on the nitrogen and oxygen stable isotope. J. Chem. 1–8 (2020).

Yu, H., Chen, C. & Shao, C. F. Spatial and temporal changes in ecosystem service driven by ecological compensation in the Xin’an River Basin, China. Ecol. Indic. 146, 109798 (2023).

Shao, W. et al. Impact of water scarcity on the Fenhe river basin and mitigation strategies. Water 9, 30 (2017).

Lawrence, C. & Lex, B. & ChinaHydro Basins. https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/KBFNSW, Harvard Dataverse, V2. (2012)..

Gong, P. et al. Stable classification with limited sample: Transferring a 30-m resolution sample set collected in 2015 to mapping 10-m resolution global land cover in 2017. Sci. Bull. 64(6), 370–373 (2019).

Zhang, X. et al. GLC_FCS30: Global land-cover product with fine classification system at 30 m using time-series Landsat imagery. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 13, 2753–2776 (2021).

Eisfelder, C. et al. Seasonal Vegetation trends for Europe over 30 years from a Novel Normalised Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) time-series-the TIMELINE NDVI product. Remote Sens. 15(14), 3616 (2023).

Baldo, M. et al. Remote sensing analysis on primary productivity and forest cover dynamics: A western ghats India case study. Ecol. Inf. 73, 101922 (2023).

Jiang, W. et al. Spatio-temporal analysis of vegetation variation in the Yellow River Basin. Ecol. Indic. 51, 117–126 (2015).

Nowosad, J. & Stepinski, T. F. Information theory as a consistent framework for quantification and classification of landscape patterns. Landsc. Ecol. 34, 2091–2101 (2019).

Su, S., Xiao, R., Li, D. & Hu, Y. Impacts of transportation routes on landscape diversity: A comparison of different route types and their combined effects. Environ. Manage. 53, 636–647 (2014).

Iskin, E. P. & Wohl, E. Quantifying floodplain heterogeneity with field observation, remote sensing, and landscape ecology: Methods and metrics. River Res. Appl. 39, 911–929 (2023).

Wang, P., Li, R., Liu, D. J. & Wu, Y. M. Dynamic characteristics and responses of ecosystem services under land use/land cover change scenarios in the Huangshui River Basin, China. Ecol. Indic. 144, 109539 (2022).

Younes, N., Joyce, K. E., Northfield, T. D. & Maier, S. W. The effects of water depth on estimating Fractional Vegetation Cover in mangrove forests. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs 83, 101924 (2019).

Zhu, L., Meng, J. & Zhu, L. Applying geodetector to disentangle the contributions of natural and anthropogenic factors to NDVI variations in the middle reaches of the Heihe River Basin. Ecol. Indic. 117, 106545 (2020).

Liu, Y., Tian, J., Liu, R. & Ding, L. Influences of climate change and human activities on NDVI changes in China. Remote Sens-Basel 13, 4326 (2021).

Gonçalves, R. M., Saleem, A., Queiroz, H. A. & Awange, J. L. A fuzzy model integrating shoreline changes, NDVI and settlement influences for coastal zone human impact classification. Appl. Geogr. 113, 102093 (2019).

Peng, W., Kuang, T. & Tao, S. Quantifying influences of natural factors on vegetation NDVI changes based on geographical detector in Sichuan, western China. J. Clean. Prod. 233, 353–367 (2019).

Jia, L. et al. Dynamic change of vegetation and its response to climate and topographic factors in the Xijiang River basin, China. Environ. Sci. Pollut R 27, 11637–11648 (2020).

Li, C. et al. Seasonal spatiotemporal changes in the NDVI and its driving forces in Wuliangsu Lake Basin, Northern China from 1990 to 2020. Remote Sens-Basel 15, 2965 (2023).

Liu, Y., Wu, G., Ma, B., Wu, T. & Wu, Q. Revealing climatic and groundwater impacts on the spatiotemporal variations in vegetation coverage in marine sedimentary basins of the North China Plain, China. Sci. Rep. 14, 10085 (2024).

Huang, C., Yang, Q. & Huang, W. Analysis of the spatial and temporal changes of NDVI and its driving factors in the Wei and Jing River Basins. Int. J. Env Res. Pub He 18, 11863 (2021).

Yang, C., Wei, T. & Li, Y. Simulation and Spatio-temporal variation characteristics of LULC in the Context of Urbanization Construction and Ecological Restoration in the Yellow River Basin. Sustainability 14, 789 (2022).

Li, J., Li, S., Wang, X., Xu, J. & Pang, J. Spatio-temporal variations and multi-scenario simulation of landscape ecological risk in the drylands of the Yellow River Basin. Sci. Rep. 14, 22672 (2024).

Jiang, L. & Li, Y. Analysis of Landscape Pattern evolution and impact factors in the Mainstream Basin of the Tarim River from 1980 to 2020. Hydrology 11, 93 (2024).

Funding

This research was funded by the Key Research and Development Project of Shanxi Province (Nos. 201803D221002-4 and 201903D321069), the Fund for Shanxi“Higher Education Teaching Reform and Innovation Project”(Nos.2022-31, J20240124) and “Jinzhong University Research Funds for Doctor”.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Zhao Ying— conceptualization, methodology, writing original draft preparation, funding acquisition ; Zhao Bingqing—validation and data curation; Wang Fei—software, validation, formal analysis, data curation, review and editing, funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhao, Y., Zhao, B. & Wang, F. Land use and landscape pattern changes in the Fenhe River Basin, China. Sci Rep 15, 2474 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86780-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86780-8