Abstract

The tumor suppressor LKB1/STK11 plays important roles in regulating cellular metabolism and stress responses and its mutations are associated with various cancers. We recently identified a novel exon 1b within intron 1 of human LKB1/STK11, which generates an alternatively spliced, mitochondria-targeting LKB1 isoform important for regulating mitochondrial oxidative stress. Here we examined the formation of this novel exon 1b and uncovered its relatively late emergence during evolution. Analyses of putative exon 1b genomic sequences within the primate superfamily indicated that the exonization of LKB1/STK11 exon 1b was mediated by the conserved retrotransposable element Alu-Sc. While putative exon 1b sequences are recognizable in most members of the primate family from New World Monkeys onwards, characteristically functional LKB1/STK11 exon 1b, with translation start and 5ʹ and 3ʹ splice sites, could only be found in greater apes and human, and interestingly, correlates with their increased body mass and longevity development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

We recently identified a novel exon (termed exon 1b) residing within intron 1 of human LKB1/STK111. Exon 1b encodes a mitochondria-targeting motif that allows a novel LKB1 splice variant (mLKB1) to translocate into the mitochondria to regulate metabolic activity and oxidative stress1. However, the corresponding “exon 1b” could not be found in the mouse genome, despite human and mouse LKB1 genes and proteins sharing > 90% identity in their mRNA and amino acid sequences, respectively2. The lack of conservation of exon 1b across these two species hints at its independent development from the rest of LKB1/STK11 exons and is suggestive of its emergence later in evolution. Considering that LKB1/STK11 is an important tumor suppressor implicated in various cancers3,4 and it plays important roles in cellular homeostasis and stress responses5,6,7,8, as well as its potential as a target for therapeutic intervention in cancer9, we examined the derivation of exon 1b during evolution in order to further understand the significance of the mLKB1 isoform in organism development.

Results

Conservation of LKB1/STK11 intron 1 among primates

The genomic structure of LKB1/STK11 is maintained across species and generally comprises 10 exons and 9 introns (without first considering the new exon 1b that we had identified earlier in human1), with intron 1 being the longest intron (Fig. 1a). While the coding regions of LKB1/STK11 are highly conserved from birds to humans2, the genomic sequence of human LKB1/STK11 intron 1 is conserved only amongst the primates. Based on NCBI-BLAST alignment score, human, chimpanzee (ape), rhesus macaque (old world monkey, OWM) and marmoset (new world monkey, NWM) share significant homology along the entire length of their intron 1. However, a much lower homology was observed with lemur which diverged from the rest of the primates in their evolution, while only 5–6% of intron 1 of mouse and dog LKB1/STK11 exhibit a good match with the human counterpart (Table 1). This finding suggests that intron 1 of primate LKB1/STK11 likely evolved independently of other mammals such as dog and mouse after their split from the rodent lineage.

Conservation of LKB1/STK11 intron 1 amongst primates. (a) Genomic structures of LKB1/STK11 of various primates, dog, mouse and chicken. The distribution of exons is conserved and intron 1 is the longest of 9 introns in all species examined. Structures are not drawn to scale. (b) Conserved distribution of SINE Alu repeats (grey boxes) in five subfamilies of primates: human, chimpanzee (ape), rhesus macaque (old world monkey, OWM), marmoset (new world monkey, NWM) and lemur. Note the lack of extensive Alu repeats in lemur. Arrows indicate conserved Alu-Sc element which overlaps with the putative exon 1b (red boxes). Analysis was based on UCSC and Ensembl genome databases. (c) DNA sequence of human LKB1/STK11 exon 1b (highlighted in yellow) with the overlapping Alu-Sc element (underlined). Red boxes indicate 3ʹ- and 5ʹ-splice sites (SS) of exon 1b. Asterisks mark the Translation Start Site (TSS).

A signature of primate genomes is their widespread incorporation of retrotransposons such as LINE (long interspersed elements) and SINE (short)10,11. Consistent with their high sequence homology, the distribution of SINEs along LKB1/STK11 intron 1 is also extensively conserved among primates of different subfamilies including humans (Fig. 1b), except for lemur which contain only the oldest Alu element (Alu-J) (Fig. 1b). A close examination of the human LKB1/STK11 exon 1b sequence that we had previously identified1 reveals that it overlaps with a forward-oriented, primate-specific SINE, Alu-Sc, within which the 5ʹ splice site (SS) of exon 1b/intron 1 is located (Fig. 1c). And likely due to the absence of Alu-Sc element, no sequence of significant homology to human exon 1b was found in the intron 1 of lemur.

Exonization of LKB1/STK11 exon 1b in primates

Next, to identify possible exon 1b in nonhuman primates, we queried LKB1/STK11 intron 1 sequences of chimpanzee, rhesus macaque and marmoset with that of human exon 1b. As shown in Fig. 2a, the putative exon 1b of chimpanzee is almost identical to human exon 1b, including the overlapping Alu-Sc element. Importantly, it possesses all the key features of a functional exon: the conserved 3ʹ and 5ʹ SS, and the translation start site (TSS) with an open reading frame (ORF). However, while both rhesus macaque and marmoset have recognizable putative exon 1b sequences, they appear to be nonfunctional as they lack the conserved 5ʹ SS and TSS. In addition, rhesus macaque and marmoset have additional 44-bp and 30-bp insertion within their putative exon 1b respectively, that disrupt their ORF.

Exonization of LKB1/STK11 exon 1b. (a) Sequence alignment of exon 1b of four subfamilies of primates as indicated. Red boxes indicate the conserved ‘AG’ residues of 3ʹ-SS and ‘GT’ of 5ʹ -SS. Note that the 5ʹ SS of marmoset and rhesus macaque are not formed. Red asterisks indicate the position of TSS encoded in human exon 1b. Black line indicates the overlapping Alu-Sc sequence in exon 1b; green boxes indicate the additional 44 bp and 30 bp of Alu-Sc sequence retained in rhesus macaque and marmoset, respectively. (b) Schematic depiction of putative exon 1b of various primates. Note that the 5ʹ SS of baboon, rhesus macaque and marmoset are not conserved and the latter two also lack TSS. (c) Alignment of consensus Alu-Sc sequence and the Alu-Sc sequences embedded in human exon 1b (bolded), and putative exon 1b of rhesus and marmoset.

We proceeded to identify potential exon 1b in other primate genomes, particularly those of the ape subfamily. Besides chimpanzee, all other greater apes including gorillas, bonobos and orangutans possess potentially functional exon 1b in their LKB1/STK11 loci, characterized by the conserved 3ʹ and 5ʹ SS, and TSS with ORF (Fig. 2b). Interestingly, gibbons from the lesser ape subfamily do not have a functional exon 1b. Although their two SS and TSS are intact, a G > T transversion at position 97 from the TSS introduces an in-frame stop codon that prematurely terminates exon 1b translation, thereby preventing the production of a full-length alternative splice LKB1/STK11 variant. Notably, as the G nucleotide at position 97 is conserved in primates, the G > T mutation in gibbons likely arose independently after their divergence from the lineage leading to greater apes about 20 to 16 million years ago (mya)12,13.

Interestingly, we found that the 44-bp and 30-bp insertions (Fig. 2a, b) in the putative exon 1b of OWMs (rhesus macaques, baboons) and NWMs (marmosets) are part of the actual Alu-Sc element (Fig. 2c), implying that they were deleted during evolution giving rise to the ape/hominoid lineage approximately 30 to 25 mya13. This deletion event helped create an intact exon 1b ORF in greater apes.

We further noted that the conserved 3ʹ SS of putative exon 1b, located within intron 1, was present from the start of simian evolution, as seen from marmosets to chimpanzees (Fig. 2a,b), whereas the 5ʹ SS only evolved after divergence of the OWM lineage, with point mutations converting either CT of marmoset or GA/GG of rhesus/baboons to GT in apes and hominids (Fig. 2a, b). However, the generation of TSS is thought to occur not long before the appearance of 5ʹ SS, as both functional and undeveloped TSS are found in OWM (Fig. 2b).

Expression of LKB1 exon 1b

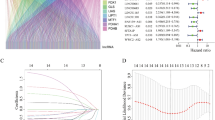

Next, we went on to investigate the usage of exon 1b using various human/primate tissue and cell-line RNA-seq datasets (Supplementary Table 1). We found evidence of exon1b usage in human heart tissues. However spliced junction read coverage across exon 1 and exon1b or exon1b and exon2 (Fig. 3) could not be confirmed in apes (chimpanzee, gorilla and orangutan), possibly due to various reasons as discussed below.

Expression of LKB1 exon 1b in primates. Sashimi plot showing read coverage across LKB1/STK11 in Human, Chimp, Gorilla and Orangutan from published RNA-seq datasets. RNA-seq read densities along exons are plotted using histograms and reads covering splice-junctions are shown using arcs with numbers on the arc representing number of junction reads. Exon numbers are marked in black. RNA-seq data for human were downloaded from PMID: 35841888, PRJEB65856; chimp, gorilla and orangutan data were from PMID: 22012392, PRJNA143627.

Overall, our analyses reveal that only the genome of human and potentially those of greater apes encode a functional LKB1/STK11 exon 1b that could lead to the expression of a mitochondria-targeted LKB1 variant.

Discussion

We analyzed the events leading to the emergence of LKB1/STK11 exon 1b during evolution. We postulated that exon 1b formation began during the period of Alu-Sc amplification and expansion in the primate genomes11, with an Alu-Sc integrating into LKB1/STK11 intron 1 around 55 to 40 mya before the split of platyrrhines (NWM) and catarrhines (OWM and Apes). Subsequently, over a period of 22 million years from 40 to 18 mya, three molecular events occurred and shaped exon 1b into its current form in greater apes and humans: (1) generation of an alternative TSS, (2) formation of an optimal 5ʹ SS within Alu-Sc sequence, and (3) partial deletion of Alu-Sc sequence (44-bp) to generate an intact ORF that accounts for most of the coding sequence of exon 1b (> 80%).

Our analysis of published RNA-seq data confirmed the presence of exon1b transcripts in human hearts (Fig. 3), however, we were not able to confirm the usage of exon 1b in apes. Low expression of exon1b (as seen in humans) and thus data depth of primate data as well as other factors such as cell or organ type specificity and age variation in samples could also lead to missed detection.

The formation of exon 1b enables the generation of an alternatively spliced LKB1 variant that localizes to the mitochondria1. Interestingly, the presence of this mitochondria-targeted LKB1 variant coincided with the evolution of primates with increasing body mass and longer lifespan (Fig. 4). Our previous findings that mLKB1 plays critical roles in increasing ATP production and enhancing protection from oxidative stress and DNA damage1, are consistent with the contribution of mLKB1 variant to the evolution of higher order primates.

Schematic depiction correlating exon 1b emergence and primate evolution. Reconstruction of the time course of exon 1b exonization, the expected expression of the mitochondria-targeted LKB1 variant and its correlation with the increase of body mass/lifespan of hominids (humans and great apes). Data on body weight and lifespan were obtained from AnAge (The Animal Ageing and Longevity Database) and Wisconsin National Primate Research Center.

Methods

Sequences and comparative analysis

LKB1/STK11 sequences were retrieved from UCSC (University of California Santa Cruz) and Ensembl Genome repositories. Accession numbers of the sequences are as follows: human (NM_000455.5); chimpanzee (XM_024351141.1); bonobo (XM_003813750.3); gorilla (XM_019015203.2); orangutan (XM_024236581.1); gibbon (XM_012503456.1); rhesus macaque (NM_001261670.1); baboon (XM_009193020.2); marmoset (XM_035285263.1); lemur (XM_012745790); mouse (NM_011492.5); dog (XM_038568023.1) and chicken (NM_001045833.1). Retrieved sequences were aligned and regions of similarity identified using the online analysis tools: NCBI-blastn function supported by National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI), and Clustal Omega supported by EMBL’s European Bioinformatics Institute for the interspecies comparative analysis. Data on body mass and lifespan of primates were abstracted from AnAge (The Animal Ageing and Longevity Database) as well as the Wisconsin National Primate Research Centre (Primate Factsheets and Resources).

Analyses of published RNA-sequencing data

RNA-sequencing data for Pan troglodytes, Gorilla and Orangutan were downloaded from PRJEB65856 (PMID: 36806354), PRJNA143627 (PMID: 22012392) and PRJNA563344 (PMID: 34035253) studies. Raw fastq files from PRJEB65856 for Pan troglodytes and Gorilla samples were trimmed for adaptors using Trimgalore v0.6.10 (https://github.com/FelixKrueger/TrimGalore) as described in the study. Paired-end reads were mapped using STAR v2.7.10a (PMID: 23104886) to Pan troglodytes genome version Clint_PTRv2 panTro6 and gorGor6 using standard parameters for full-length RNA-seq in the ENCODE project. Raw fastq files from PRJNA143627 and PRJNA563344 for Pan troglodytes, Gorilla and Orangutan samples were mapped using STAR v2.7.10a to Pan troglodytes genome version Clint_PTRv2 panTro6, gorGor6 and ponAbe3 genomes using parameters as described for standard full-length RNA-seq in the ENCODE project. RNA-sequencing data of 162 samples for human was obtained from PRJNA756023 (PMID: 35841888) and pooled data (1.8B mapped reads to human genome version hg38) across all six cell-types (Endothelial cells, hepatocytes, atrial fibroblasts, vascular smooth muscle cells, embryonic stem cells) and five tissues (Brain, fat, heart, kidney, skeletal muscle) were used to test the presence of exon 1b.

Data availability

The sequences retrieved and analyzed during current study are available in the UCSC genome repository (https://genome.ucsc.edu) and Ensembl genome repository (https://www.ensembl.org).

References

Tan, I. et al. Identification of a novel mitochondria-localized LKB1 variant required for the regulation of the oxidative stress response. J. Biol. Chem. 299, 104906–104916 (2023).

Smith, D. P., Spicer, J., Smith, A., Swift, S. & Ashworth, A. The mouse Peutz–Jeghers syndrome gene Lkb1 encodes a nuclear protein kinase. Hum. Mol. Genet. 8, 1479–1485 (1999).

Sanchez-Cespedes, M. et al. Inactivation of LKB1/STK11 is a common event in adenocarcinomas of the lung. Cancer Res. 62, 3659–3662 (2002).

Waddell, N. et al. Whole genomes redefine the mutational landscape of pancreatic cancer. Nature 518, 495–501 (2015).

Alessi, D. R., Sakamoto, K. & Bayascas, J. R. LKB1-dependent signaling pathways. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 75, 137–163 (2006).

Shackelford, D. B. & Shaw, R. J. The LKB1-AMPK pathway: metabolism and growth control in tumour suppression. Nat. Rev. Cancer 9, 563–575 (2009).

Shaw, R. J. LKB1: cancer, polarity, metabolism, and now fertility. Biochem. J. 416, e1-3 (2008).

Xu, H. G. et al. LKB1 reduces ROS-mediated cell damage via activation of p38. Oncogene 34, 3848–3859 (2015).

Shackelford, D. B. et al. LKB1 inactivation dictates therapeutic response of non-small cell lung cancer to the metabolism drug phenformin. Cancer Cell 23, 143–158 (2013).

Deininger, P. Alu elements: know the SINEs. Genome Biol. 12, 236–247 (2013).

Konkel, M. K., Walker, J. A. & Batzer, M. A. LINEs and SINEs of primate evolution. Evol. Anthropol. 19, 236–249 (2010).

Kim, S. K. et al. Patterns of genetic variation within and between Gibbon species. Mol. Biol. Evol. 28, 2211–2218 (2011).

Shao, Y. et al. Phylogenomic analyses provide insights into primate evolution. Science 380, 913–924 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This project was funded by A*STAR SIgN. SC is funded by Singapore Ministry of Health’s National Medical Research Council under OF-YIRG (OFYIRG23jan-0034).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

IT performed experiments; SC analyzed RNA-seq datasets; IT, HHL, KPL conceptualized project, wrote and edited the manuscript. KPL obtained resources required for this project.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tan, I., Chothani, S., Lim, HH. et al. Alu-Sc-mediated exonization generated a mitochondrial LKB1 gene variant found only in higher order primates. Sci Rep 15, 3360 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86789-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86789-z