Abstract

As the depth of coal mining in China continues to increase, the fracturing of coal rock masses has an increasingly complex impact on the surrounding rock roadways. The majority of the mine’s roadways run through coal rock masses with hard roofs and soft bottoms, which typically exhibit complex dynamic behaviour. To further research the mechanical behaviour and fracture evolution of coal rock masses under hard-roof and soft-floor conditions, the study is based on the majority of working faces in a mine, which have hard roofs and soft floors. Uniaxial compression tests were utilized to study the mechanical properties of coal rock masses under hard-roof and soft-floor circumstances, using acoustic emission monitoring, whole-process imaging technologies, and fractal dimension analysis. The experimental results are as follows: The uniaxial compressive strength of the coal rock mass is significantly higher than that of its weakest component. The results of the experiment are as follows: The uniaxial compressive strength of coal rock mass is significantly higher than that of its weakest component. Samples with different soft rock strengths exhibited dissipated energy greater than the accumulated energy before the stress maximum, accompanied by volume expansion and the formation of shear surfaces. Samples with higher soft rock strengths tend to exhibit brittle failure, while weaker samples show stress-softening behaviour. Internal fracture complexity varies amongst samples with varying soft rock strengths. A fractal study of the acoustic emission parameters was carried out utilizing MATLAB programming. The fractal analysis results show that acoustic emission ringing counts and energy time series of coal rock masses under hard-roof and soft-floor settings have good fractal properties. The fractal analysis results show that acoustic emission ringing counts and energy time series of coal rock masses under hard-roof and soft-floor settings have good fractal characteristics. Acoustic emission ringing counts tend to have a larger correlation dimension than acoustic emission energy. However, while the sample is fracturing on a vast scale, the ringing count correlation dimension fluctuates very little. The correlation dimension distribution of samples with lower strength is more concentrated after the stress maximum, implying that the deformation and fracturing of the floor rock in highways under hard-roof and soft-floor circumstances are more complex. Both the correlation dimension D of acoustic emission ringing counts and energy indicate a continuous fall before peak stress, which can be used to anticipate coal rock mass fracture. This study, based on the mechanical behaviour and fracture evolution of coal rock masses under hard-roof and soft-floor conditions, provides a foundation for disaster avoidance by controlling the stability and structural deformation of floor rock in hard-roof and soft-floor highways.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With increasing mining depth, deep rock masses exhibit typical high-ground stress. Based on the mechanical behaviour and fracture evolution of coal rock masses under hard-roof and soft-floor conditions, this study provides a foundation for disaster avoidance by managing the stability and structural deformation of the floor rock in hard-roof and soft-floor highways. This causes the coal rock to evolve from progressive fracture to catastrophic instability1,2,3,4,5,6. Roadways under hard-roof and soft-floor circumstances are those where the roof rock has a uniaxial compressive strength of 60 MPa or more and the floor rock strength is less than 60 MPa. These roads are susceptible to unknown coal rock mass deformation and fracturing, posing a risk to safe production7,8. The fracture of coal rock masses is frequently accompanied by a dramatic rise in acoustic emission signals, which indicate the production and development of cracks and the collection and release of energy. As a result, acoustic emission monitoring, fractal dimension analysis, and other techniques are used to undertake an in-depth study of the fracturing mechanisms and evolution patterns of coal rock masses under hard-roof and soft-floor conditions; and to quantitatively characterize the initiation, propagation, and coalescence of cracks.

Existing studies have shown that the coal-rock failure is connected to mechanical characteristics, stress environment, and the nature of the roof and floor. These factors often determine the strength of coal-rock combinations and the overall safety of the mining site9,10,11,12. The coal-rock system consists of strata that alternate between coal and rock. A rock-coal-rock combination is usually used to simulate the instability and failure process in mining sites more accurately. Multiple factors influence coal-rock combinations’ mechanical behaviour and fracture process. For example, the energy proportion13, failure modes14, crack initiation location and complexity15, compressive strength16, and the bonding degree of the coal-rock interface17 differ under various coal-rock bonding forms. However, these studies have not fully revealed the fracture characteristics of coal-rock combinations under hard roof-soft floor conditions.

Acoustic emission (AE) is widely used for high-sensitivity monitoring of coal-rock damage18,19. Both local and international experts have conducted substantial research into the features of AE signals during coal-rock failure. For example, Qing Ma et al. investigated the variations in AE counts during the uniaxial compression failure of coal-rock20; Zhao et al. found that in coal-rock combinations, the number of AE events in coal exceeds that in rock21; Du et al. observed that different fracture modes exhibit different AE frequencies. The low average frequency and low peak frequency correspond to shear cracks, while tensile cracks dominate samples with low RA values and high peak frequency22. Zabihallah Moradian et al. discovered that the number of AE strikes is connected to the number of cracks and the AE energy is related to the magnitude of fracture events23; Longjun Dong et al. investigated the qualitative link between instability antecedents and the primary stress direction of wave velocity in rock AE tests24; Liping Li et al. discovered that peak AE energy is linked to the roughness of the coal-rock contact25; This reflects the relationship between AE parameter characteristics and crack development. The complexity of cracks is closely related to the fractal dimension of the samples. As scholars combine fractal theory with rock damage mechanics, Tang et al. employed fractal theory and damage mechanics to compute the fractal dimensions of coal-rock combinations with varied angles under various damage levels26. Jian Yang et al. explored the AE parameters of different rock-like materials and the trend of fractal dimension changes over time during the fracture process27. Chengjie Li et al. found that the crack angle and position of composite samples are related to energy dissipation and fractal characteristics28; Zhao et al. observed that the lowest fractal dimension during sample deterioration is often between 70% and 90%: the AE amplitude, event rate, energy rate, and spatial distribution of sandstone exhibit fractal qualities. A quantitative examination of the development of fractal dimensions in freeze-thaw settings was done29,30. Although there is a certain correlation between acoustic emission parameters and fractal dimensions, how to use these characteristics to explain the fracture evolution of coal-rock masses under hard roof-soft floor conditions remains a topic worthy of in-depth study.

This study explores the mechanical properties and fracture characteristics of coal-rock masses under both hard-roof and soft-floor conditions, using a typical working face from a specific mine as the research background. Uniaxial compression tests were performed after processing the rock samples provided by the mine. The fracturing of the coal-rock mass was recorded using acoustic emission monitoring and whole-process imaging technology. The energy evolution features of samples of various strengths were investigated using the conservation of energy theorem. Using the Sentinel function, the total energy of the composite samples was linked to the acoustic emission energy. The Sentinel function curve was utilized to quantitatively examine the fracture evolution process in coal-rock composite samples. The study examines the acoustic emission ringing and energy characteristics of samples with different soft rock strengths throughout the loading procedure. In addition, it studies sample fracture and interior damage mechanisms using macrocrack analysis. The correlation dimensions of AE ringing counts and energy for coal-rock composites of varying strengths have been calculated using fractal theory, and their variations during the loading process were discussed. The objective of this work is to expose the complexity of coal-rock mass fracturing under hard-roof and soft-floor settings by evaluating fracturing evolution characteristics using experiments and data analysis. The results are likely to provide a foundation for maintaining roadway stability while controlling deformation under similar circumstances.

Engineering background

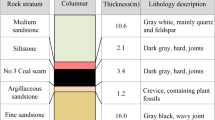

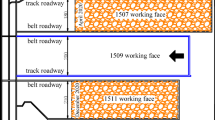

The mining field extends approximately 10.5 km from east to west and 6.4 km from north to south, covering a registered area of about 41.98 km2. It has a designed production capacity of 4.00 Mt/a and a service life of 63.7 years. According to a small-scale investigation of surrounding rock roadways in most working faces of the mine, thick and hard rock layers, resistant to collapse, are often present above the coal seam, while the coal seam rests on a soft rock floor. In many unsupported roadways near the goaf, roof suspension in the goaf induces lateral strut pressure, leading to severe bottom drum issues in the return air roadway.

To explore the reasons for the bottom drum in the return air highway at the goaf in the mine’s working face, uniaxial compression tests were performed on roof, floor, and coal seam samples provided by the mine. The hard roof is mostly made of sandstone, while the floor is made up of four types of rock: sandy mudstone, mudstone, siltstone, and red sandstone. Coal-rock composites were employed to investigate the mechanical characteristics and fracturing evolution patterns of coal-rock masses under both hard-roof and soft-floor circumstances.

Combined coal-rock failure test

Sample preparation

The deformation and fracture of coal-rock combination samples mainly occur in the coal and soft rock layers. The strength of the coal-rock combination is influenced by the height of the central coal layer11. When the height-to-diameter ratio of the sample is 2 and the coal layer thickness is 30–40 mm, cracks appear. However, when the coal layer thickness increases to 50 mm, no cracks are observed15. To observe Coal and soft rock fracture and deformation at varying strengths, a coal layer thickness of 30 mm was chosen for the experiment. Following the standards of the International Society for Rock Mechanics, the height-to-diameter ratio of the samples was set between 2.0 and 3.0, the flatness of the bottom did not exceed 0.02 mm, and the maximum deviation of the axis was less than 1/1000 of the width31. The materials used in the experiments included sandstone, coal, sandy mudstone, mudstone, siltstone, and red sandstone. To prevent weathering, the coal-rock samples collected on-site were kept intact and transported to the laboratory in a sealed condition.

Using the coal-rock mass samples provided by the mine, three sets of cylindrical samples with a diameter of 50 mm and a height of 100 mm were prepared. Before conducting the uniaxial compression tests, basic mechanical parameter tests were carried out on six standard samples each of rock and coal. The test results are shown in Table 1. Hard rocks and soft rocks were processed into cylinders with a diameter of 50 mm and a thickness of 35 mm, whereas coal blocks were processed into cylinders with a diameter of 50 mm and a thickness of 30 mm. Coal samples and rock samples were bonded together using a high-strength, fast-curing epoxy glue. Based on the strength of the soft rocks, the composite samples were divided into four groups, as shown in Table 2.

Test system

The loading module, the acoustic emission monitoring module, and the high-speed camera make up the experimental system, as depicted in Fig. 1. The uniaxial compression tests were conducted using the MTS-600 rigid servo control testing system, and the DS-5 full-waveform AE acquisition system (with a maximum sampling frequency of 10 MHz) was used to collect AE signals. The AE acquisition frequency was set to 3 MHz. The amplifier was calibrated to 30 dB, and the AE system was set up using the pencil lead break method, as advised by ASTM. A high-speed camera was turned on to capture the sample’s dynamic failure process, and four sensors were positioned on either side of the object (as seen in Fig. 1). Before the test, a coupling agent was applied at the points of contact between the probes and the sample surface to eliminate friction interference.

The experiment used displacement-controlled loading. Before starting the test, a uniaxial loading rate of 4 μm/s was set. The acoustic emission sensors were bonded to both sides of the sample using a hot-melt adhesive. The acoustic emission system was calibrated using the pencil lead break method to ensure the proper functioning of the system. During the experiment, AE signals, stress data, and image information were collected simultaneously. When the applied load fell to 60% of its highest value, data recording was terminated.

Test results

Figure 2 displays the findings of the uniaxial compression test, and Fig. 3 shows the comparison of UCS of coal-rock combinations with different strengths and their minimum rock sample UCS. In sample RCR-1, the curve appears serration joint type, with post-peak stress repeatedly rising and falling, showing an overall downward trend. In samples RCR-2, RCR-3, and RCR-4, the curve exhibits a longer shear slip stage near peak stress and a step-like decline after the peak. The peak stresses of the composite samples RCR-1, RCR-2, RCR-3, and RCR-4 reached 24.43 MPa, 9.4 MPa, 6.94 MPa, and 4.71 MPa, respectively. The compressive strength of the coal-rock composite samples was greater than that of the weakest single standard rock sample, as Fig. 3 illustrates. Specifically, the compressive strengths of RCR-1, RCR-2, RCR-3, and RCR-4 increased by 79.37%, 33.71%, 40.2%, and 61.64%, respectively, compared to the weakest rock strength. The analysis suggests that the end effects limited the deformation of the coal rock, enhancing the overall compressive capacity of the samples. In sample RCR-1, the end effects limited the deformation of the coal, and when the load reached the critical value, the sudden release of energy caused impact failure. The research, as mentioned earlier, indicates that a key factor in the failure process of composite samples is the soft rock’s strength. As the soft rock strength declines, the coal rock mass experiences significant deformation following the stress maximum.

Combined with the image information of the entire loading process, the dynamic evolution of fractures in coal-rock combinations can be tracked from the initiation of cracks to their propagation and eventual coalescence, gradually transitioning from gradual change to sudden change. The macroscopic failure analysis of coal rock reveals rich information about the deformation, force chain evolution paths, and crack propagation of coal rock32,33,34.

The macroscopic failure patterns of composite samples with varying strengths are displayed in Fig. 4. The first phases of loading in the RCR-1 sample showed no discernible alterations. However, when the stress reaches 51.62% of the stress maximum, the coal initially fractures. When the load got close to its peak, the dissipated energy (EH) was mainly reflected in the continuous falling of coal debris, with cracks primarily forming in the coal and the number of axial cracks increasing. When the stored energy (ET) reached its limit, the coal and soft rock failed at the peak stress. The crack spread to the floor, producing a muffled sound and ejecting a huge amount of coal dust and a minor amount of rock debris. A shear fracture zone with an “X” shape was formed after the failure. Subsequently, when the load increased to 81.19% of the stress maximum, the crack quickly propagated through the soft rock and coal. A “crash” sound was heard, accompanied by the rapid expansion of the fracture, as shown in Fig. 4a. This corresponds to the multiple internal damage deformations observed in RCR-1’s post-peak stress-strain curve. The energy input from the roof and floor and the end effects promoted the development of cracks in the rock layers, ultimately resulting in the coal-rock combination’s failure. In samples RCR-2, RCR-3, and RCR-4, cracks initiated in the soft rock and extended to the coal when the load reached 76.38%, 59.89%, and 43.31% of the stress maximum, respectively (as shown in Fig. 4b–d). These three samples mainly exhibited shear failure. Tensile-shear failure became the predominant mode of failure as the strength declined, causing the soft rock and coal’s stored energy to rise and the coal’s end effects to diminish. The overall failure was exacerbated by the local floor failure, which released the stored energy in the coal. This decreased the energy intake and the number of damage cycles of the samples. In contrast to RCR-1, all three samples exhibited a progressive reduction in stress during the post-peak stage, accompanied by a widening of the fractures in both soft rock and coal. Eventually, the cracks penetrated the coal-rock combination without resulting in impact failure. The soft rock’s unloading effect, which lessened the coal’s violent failure, is explained by this. As the load decreased from 100 to 60% of the stress maximum, the fissures in the coal and soft rock widened and consolidated, resulting in volume expansion and the formation of a shear surface.

In conclusion, and in line with previous research findings35,36, the strength of the coal becomes the primary determinant of the composite sample’s stability for the highest-strength sample, RCR-1. The soft rock’s strength determined the samples’ overall stability for the lower strength samples RCR-2, RCR-3, and RCR-4, with the smooth rock showing a favorable unloading effect. This is because of the buildup of internal damage in soft rock and coal beyond their failure thresholds, resulting in first failure and general fracture. This suggests that the material’s failure mode is shifting from brittle to ductile as a result of the strength loss.

Analysis of fracture states in coal-rock combination samples

An investigation of energy and acoustic emission characteristics was carried out to explore and better understand the energy release features and fracture process of coal-rock combinations under stress. The energy release behaviour of coal-rock combinations under stress is better-understood thanks to our approach, which also identifies energy spikes in coal-rock combinations of varying strengths. It facilitates comprehension of how fractures begin, spread, and consolidate during coal-rock fracture. Based on the experimental results, the acoustic emission data of the coal-rock mass during the loading process were recorded and analyzed as follows.

Energy evolution analysis

The conservation of energy theorem and the first law of thermodynamics presume that the composite sample does not exchange heat with the surrounding environment when subjected to external pressures. In the experiment, the composite sample is subjected to uniaxial stress that results in a total energy Ei(t) that is made up of the sum of the stored energy ET and the dissipated energy EH. The composite samples’ energy conversion relationships from the uniaxial compression test are displayed in Fig. 5. This allows for the derivation of the formula for the change in total energy Ei(t) over time during the loading process37:

In the equation, σi is the stress value found on the stress-strain curve at any given location, the initial values are all 0 MPa, and the decompression path of the combined sample before the peak remains essentially the same as the slope of the linear elasticity phase. Therefore, the scattered energy EH and stored strain energy ET during the loading process were calculated using the following formula:

In the equation, \({\sigma _f}\) and \({\varepsilon _f}\)is the peak stress and strain; \({\varepsilon _e}\) is the irrecoverable strain, and the area under the stress-strain curve is and the energy released following the peak, EF is \({\varepsilon _f}\) to \({\varepsilon _g}\) :

The highest strain found during the loading test is included in the calculation. A portion of the combined sample’s stored strain energy is released with the formation of the fracture at the arrival of the post-peak. In contrast, another portion is transformed into residual energy. When the combined sample is destroyed, its mechanical characteristics are directly connected to the ratio η between the energy EF released after the peak and the stored strain energy ET.

According to the calculation formula, the energy results during the loading process are shown in Table 3. As energy continues to be input, some energy EH is released, primarily reflecting the development of initial cracks. In addition, a portion of the energy is simultaneously stored as ET in the sample. When the strength limit is reached, this energy partially converts to EF, primarily manifesting in the merging and penetration of cracks. As shown in Table 3; Fig. 6a, before the stress maximum, the total energy Ei of the composite samples were 0.1173 J×mm− 3, 0.0578 J×mm− 3, 0.0420 J×mm− 3, and 0.0231 J×mm− 3, and the stored energy ET were 0.1015 J×mm− 3, 0.0433 J×mm− 3, 0.0282 J×mm− 3, and 0.0169 J×mm− 3, correspondingly. The samples don’t become unstable until the energy is input from outside sources beyond its strength threshold. Therefore, sample RCR-1 has the highest strength, indicating that its dissipated energy EH before the stress maximum is the largest, at 0.0158 J×mm-3. The dissipated energy EH of samples RCR-2, RCR-3, and RCR-4 are smaller, at 0.0145 J×mm− 3, 0.0138 J×mm− 3, and 0.0062 J×mm− 3, correspondingly. This indicates that the damage to the composite sample of RCR-1 before the peak is greater than that of RCR-2, RCR-3, and RCR-4, and it experienced more plastic deformation. Crack formation is intimately associated with post-peak energy evolution. The η values of the samples are 66.21%, 117.32%, 68.09%, and 171.01%, respectively. This indicates that during uniaxial compression, soft rock undergoes a significant stress-softening stage. After peak stress, a large amount of strain energy is rapidly released in various forms, accompanied by complex structural changes. Sometimes, this energy release exceeds the pre-peak stored strain energy, consistent with the description in the literature35. The post-peak released energies of RCR-1, RCR-2, RCR-3, and RCR-4 are 0.0672 J×mm− 3, 0.0508 J×mm− 3, 0.0192 J×mm− 3, and 0.0286 J×mm− 3, correspondingly. As shown in Fig. 6(b), sample RCR-4 has the largest η value, with its dissipated energy (EF) after the stress maximum exceeding the stored energy (ET) before the stress maximum. This explains that as the axial stress increases, the sample undergoes volume expansion and the formation of shear surfaces.

Therefore, considering the coal-rock combination’s energy evolution features, before the stress maximum, sample RCR-1 showed more complex cleavage. In contrast, after the peak, sample RCR-4 showed greater volume expansion owing to the deformation instability of the soft rock. Furthermore, there exists a strong correlation between the loading test sample’s damage level and the cumulative energy of the AE. The formulas for this computation are as follows:

where Ei is the AE energy at any time.

To conduct a quantitative analysis of the coal-rock combination’s rupture process, the total energy was related to the assembled samples based on the sentry function. Equation (5) describes the ratio of the total power generated by the uniaxial load work on the combined sample to the cumulative AE energy \({E_{AE}}(t)\) with time (t) as follows:

In the equation, κ is a tiny quantity, and t is an arbitrary time with an initial value of 0.

The first notable drop point in the sentry function curve typically indicates when deterioration of the composite sample starts19. Due to possible early defects in the sample, which may trigger AE signals in the initial stages, data from the compaction phase (0 to 75 s) were excluded from the analysis. As shown in Fig. 7a–d (The green dots represent special points). the sentry function curve’s initial notable decline occurs at 179.62s, 193.75s, 125.94s, and 107.48s, corresponding to loading stresses of 51.62%, 76.38%, 59.89%, and 43.31% of the peak stress, respectively. When the applied stress hits a specific threshold, the Sentry function curve exhibits a considerable downward tendency. This means that the acoustic emission (AE) signals of coal rock samples become active when the stress reaches 83.17%, 94.79%, 75.71%, and 87.08% of the peak stress, respectively.

Three stages of fracture damage are identified based on the composite sample’s loading procedure and the sentry function’s trend. In the OA stage, also known as the “strain energy storage stage,” structural damage to the sample can be neglected. When the stored energy reaches the threshold38, microcracks appear, causing a significant drop in the curve \(\xi\)(t) and generating a large number of AE signals. This marks the beginning of the AB stage, where AE signals enter an active phase. The BC stage is when the sample develops from microcracks to significant cracks until fracture, during which the sample’s bearing capacity gradually deteriorates.

The sentry function was utilized to conduct a quantitative analysis of the damage development process of the sample, and the energy evolution features of the sample were studied to study the energy conversion laws of the coal-rock combination during the loading process.

AE response during the loading process

Numerous academics have done a great deal of research using acoustic emission (AE) technologies to analyze the progression of failure in composite samples39. When the composite samples are loaded, as can be shown in Fig. 8, their AE signals change with time. The beginning, development, and penetration of cracks in coal-rock composite samples are accompanied by AE events during the failure process. The composite sample’s stress releases a significant amount of strain energy in the form of coal-rock combination fracture when it reaches the critical value, producing AE signals. The shown in Fig. 8a–d, different stages of fracture development are represented by different AE signals in coal-rock composite samples RCR-1, RCR-2, RCR-3, and RCR-4.

-

(1)

Stable growth phase (OA): This stage includes the compaction phase of the composite sample and part of the linear elastic phase. During this stage, AE signals are few and mainly sporadic, with a low energy index. Analysis shows that microcracks in coal and soft rock stably propagate at the microscopic level, while microcracks in hard rock are few. Cumulative ringing count and AE energy analysis show that, except for some strong local signals, the ringing count increases approximately linearly. In the linear elastic phase, microcracks in sample RCR-1 mainly propagate in the coal body, while microcracks in RCR-2, RCR-3, and RCR-4 mainly propagate in the soft rock. As the rock strength increases, the number of microcracks in coal and soft rock increases, and correspondingly, AE signals gradually increase until the stress reaches point A, where macro cracks occur in the composite sample. Therefore, under low load, the cumulative ringing count shows an approximately linear increase.

-

(2)

Stage of accelerated expansion (AB): The composite sample’s plastic stage and linear elastic portion are covered in this stage. The sensors detect a considerable increase in continuous AE signals during this stage. The cumulative ringing count increases at a faster rate, and the energy is significantly higher than in the OA stage. Based on analysis, sample RCR-1 exhibits cracks that propagate quickly from the microscopic to the macroscopic level. This process releases a significant quantity of energy and generates active AE signals. Simultaneously, the microcracks in the soft rock of samples RCR-2, RCR-3, and RCR-4 also extend to macroscopic cracks. As the load increases, the ringing count in this stage shows exponential growth. In the course of the composite samples failing, energy accumulation (ET) and dissipated energy (EH) are significant, AE signals are dense, and multiple energy peaks are observed.

-

(3)

Stage after peak (BC): The sample moves from a state of maximum stress to one in which coal and soft rock have completely fractured. At this point, the sample releases a significant quantity of strain energy, and the cumulative ringing count accelerates even further. The energy of AE signals increases significantly, with maximum energy values reaching 25330.0, 2146.6, 2155.7, and 1624.8, respectively. There are significant differences between different samples, especially under the influence of soft rock unloading: In the RCR-1 sample, the coal fractures first. As the stress increases, large cracks gradually form in the smooth rock, and the AE energy peak appears at the stress maximum. In contrast, in the RCR-2, RCR-3, and RCR-4 samples, the soft rock fractures first form large cracks, which then propagate to the coal, resulting in a relatively delayed AE energy peak. Therefore, the energy peak typically emerges after the stress maximum for samples RCR-2, RCR-3, and RCR-4, which have lower strengths than coal. Meanwhile, the cumulative ringing count continues to increase, and the AE signals are denser after the peak.

In conclusion, the energy and AE ringing count of the coal-rock combination samples changes from quiet to large surges during the loading procedure. Initial low-energy AE events occur during the compaction stage due to the closure of pre-existing cracks inside the sample and between the coal and rock, as well as the first strain energy release from the crack slide and interlock. At this point, AE signals are rather calm. Because hard rock, soft rock, and coal have different rock properties, the composite sample mostly experiences elastic deformation during the linear elastic stage, and the AE energy stays low. The AE signals begin an active phase following loading to point A when the number of cracks increases and the stress gets closer to the peak, and this causes the cumulative AE count to climb exponentially during the AB stage. This indicates the generation of a large number of microcracks and verifies the feasibility of quantitatively analyzing the fracture process of coal-rock combinations based on the sentry function curve. Entering the elastoplastic stage, with the continuous expansion of cracks, high-energy events occur frequently, exhibiting more intense damage and longer event durations. Continuous high-energy events also mark the AE signals entering an active phase. The sentry function curve at this point and the active phase of AE energy correlate, as seen in Figs. 7 and 8, providing insight into the microscopic failure features of coal-rock combination samples at various fracture phases.

Therefore, combining the macroscopic fracture behaviour and AE parameter characteristics, significant differences are observed in mixes of coal and rock with varying intensities. The abrupt failure of coal is the primary cause of the initial increase in AE signals during the dynamic fracture process of sample RCR-1. Cracks begin in the coal and extend to the soft rock, eventually forming through-going cracks. For the weaker soft rock samples RCR-2, RCR-3, and RCR-4, the initial surge in AE signals reflects the gradual failure of the smooth rock. The failure of the coal frequently happens concurrently with high-energy events that are linked to the creation of cracks in the soft rock. In the strongest sample, RCR-1, coal may undergo impact failure. In the weaker samples RCR-2, RCR-3, and RCR-4, the floor rock layers are more prone to large deformations. Due to the unloading effect of the soft rock, the complexity of coal fracture is reduced. Higher-strength samples exhibit higher energy release and more complex crack networks. The crack form is noticeably more complicated than in lower-strength samples, and the crack propagation speed is quick, especially in the highest-strength sample, RCR-1.

Fractal properties of coal-rock combinations with varying strengths

Fractal characteristics of AE energy and ringing count

The fractal dimension can be utilized to characterize the multiple cracks of various sizes created during coal-rock fracture. This allows for a quantitative analysis of the complexity of crack propagation in coal-rock throughout the failure process. These cracks typically exhibit self-similarity in their distribution. AE signals represent the crack propagation and damage within the rock. The inherent mechanisms of rock fracture and the distribution patterns of these signals are revealed by the correlation dimension D. By calculating the fractal dimension over different periods, the evolution of the rock fracture process can be observed. Changes in the fractal dimension reflect the entire process of crack initiation, propagation, and coalescence40. Especially near the fracture peak, abrupt changes in the fractal dimension often indicate the formation of large-scale cracks. As a result, the processed acoustic emission data were imported into MATLAB, and the formulas (6), (7), (8), (9), and (10) were written there. Acoustic emission data was used to calculate the time-dependent fractal dimension (D) during loading for composite samples RCR-1, RCR-2, RCR-3, and RCR-4. Grassberger and Procaccia’s G-P technique is used to extract the correlation dimension D directly from the time series by gathering AE signal data during rock rupture. A new dimension can be created as a result of the variables within each state of the fractal set changing over time under the impact of other factors. This new dimension is computed as follows27:

One way to think of the AE feature parameters is as a collection of central time series X:

To get the initial vector X1 in the space, m data are extracted from the m-dimensional phase space using these data:

Then delete x1 and take x2, x3, x4, …, xm+1 in turn to form X2 in m-dimensional space, and loop according to the above steps, thus constructing a series of phase points: X1, X2, X3, X4, …, Xn−m+1, and given a constant r, check how many of the distances between the phase points (Xi, Xj) are less than r, and record the ratio between the points less than r and N2, counted as C(r):

In the equation, the Heaviside function is denoted by H(q); N = n−m + 1; r denotes a scale; A probability cumulative distribution function is denoted by C(r), and to avoid data dispersion, as the scaling factor is denoted by k, assuming that r is obtained appropriately:

If this relationship holds, The correlation dimension is denoted by D:

After importing the experimental data using MATLAB, the fractal dimension D was calculated using the method mentioned above. It was ultimately discovered through the trial-and-error process that the phase space’s embedding dimension, mmm, was 3. The time series of AE energy and ringing count for composite samples with different strengths were analyzed, and the log-log relationship curve of lnC(r) versus lnr was calculated. When the scaling factor k is less than 0.3, the fractal characteristics are not obvious. Therefore, the range of k was chosen to be from 0.3 to 1.3 for the calculations. Through linear fitting, Figs. 9, 10, 11 and 12 were plotted.

As shown in Fig. 9a the ringing count correlation dimension D of the RCR-1 sample is 2.5907 and the correlation coefficient R is 0.9553. The energy correlation dimension D of the RCR-1 sample is 0.5191 and the correlation coefficient R is 0.9727 in Fig. 9b. As shown in Fig. 10a the ringing count correlation dimension D of the RCR-2 sample is 3.4376 and the correlation coefficient R is 0.9991. The energy correlation dimension D of the RCR-2 sample is 0.6420 and the correlation coefficient R is 0.9662 in Fig. 10b. As shown in Fig. 11a the ringing count correlation dimension D of the RCR-3 sample is 3.7162 and the correlation coefficient R is 0.9902. The energy correlation dimension D of the RCR-3 sample is 1.2086 and the correlation coefficient R is 0.9894 in Fig. 11b. As shown in Fig. 12a the ringing count correlation dimension D of the RCR-4 sample is 3.5227 and the correlation coefficient R is 0.9910. The energy correlation dimension D of the RCR-4 sample is 1.0830 and the correlation coefficient R is 0.9691 in Fig. 12b. The fitting coefficients of the ringing count were generally higher than those of AE energy. Still, both fitting coefficients exceeded 0.95, indicating that AE energy and ringing count exhibit significant fractal characteristics. This demonstrates even more how closely AE parameters and the sample’s fracture evolution process correlate. Additionally, because the fitting coefficients of AE parameters during the first 130 s of loading were relatively low, affecting the accuracy of the fractal dimension D, the data from this period were excluded from the analysis. Following that, relationship graphs were created for composite samples with varying soft rock strengths between the correlation dimension D and AE parameters.

Evolution characteristics of correlation dimension D over time

The correlation dimension D of the ringing count and the AE energy over time for the composite samples are depicted in Fig. 13. The correlation dimension of AE signals and time for RCR-1 are shown in Fig. 13(a). The correlation dimension curve of the ringing count changes when the loading enters the linear elastic phase (130 s), with a notable continuous decline between 150 and 170 s, suggesting the production of a few rather big cracks in the sample. The correlation dimensions D of the count and AE energy reveal a significant continuous abrupt fall when the cracks enter the non-stationary propagation stage (260s), reaching a local low at 280s, indicating the occurrence of several AE events. The correlation dimension of the ringing count increases after the stress peak, suggesting the creation of multiple new small-scale cracks at this time. The correlation dimension curves of the ringing count and AE energy show brief fluctuations when the stress enters the post-peak failure stage, indicating the rapid enlargement and penetration of large-scale cracks. This is consistent with the fracture evolution process of the composite samples that have been previously described. In general, the energy correlation dimension is smaller than the ringing count correlation dimension, yet during the stress change process, the trends of the two dimensions follow comparable patterns. The energy correlation dimension is relatively strong near the peak, whereas the ringing count correlation dimension is quite low. On the other hand, the energy correlation dimension exhibits larger fluctuations and decreases than the ringing count correlation dimension during major AE events.

Figure 13 illustrates how the variations in the energy correlation dimension and the correlation dimension of the ringing count of coal-rock combination samples with varying strengths are similar during the whole stress loading procedure. As such, a comprehensive process analysis will not be reproduced here; instead, the focus will be on their distinctions. As shown in Fig. 13b–d the post-peak oscillations in the correlation dimensions are more noticeable, and the post-peak correlation dimensions of the ringing count and energy are denser in the lower strength samples RCR-2, RCR-3, and RCR-4. This is consistent with the macroscopic crack patterns depicted in Fig. 8 and suggests that the samples are gradually failing on a broad scale because of the ongoing rise in the size of big cracks.

The internal damage complexity of coal-rock combinations is related to the fractal dimension. Research reveals that a simultaneous continuous decrease in the fractal dimensions of AE counts and energy frequently indicates the development of large-scale cracks and a straightforward internal damage mode. The coal-rock combination samples RCR-1, RCR-2, RCR-3, and RCR-4 exhibit correlation dimensions that generally indicate an increasing trend with significant fluctuation amplitudes. This suggests that the complexity of the internal damage in the samples is steadily rising, that the fracture of the coal-rock combination is becoming less orderly, and that the creation of the shear plane and volume expansion are accompanying these changes, which reflect increased internal damage in the coal-rock combination. Remarkably, the correlation dimensions D between the AE energy and the ringing count demonstrated a continuous decrease to a local minimum before the peak stress and then an increase once more. As shown in Fig. 13, the local minimum values of the correlation dimensions and the corresponding stresses are 94.59%, 93.64%, 98.28%, and 86.21%, respectively. Combined with the AE parameter characteristics and macroscopic crack dynamic evolution, the continuous decline in the correlation dimensions before the peak is a precursor to the critical failure of the coal-rock combination.

Conclusion

In this study, uniaxial compression tests were conducted on coal-rock combinations with soft rock unloading effects. The study integrated acoustic emission (AE) monitoring, full-process imaging technology, and fractal dimension analysis to investigate the fracture dynamics, AE responses during loading, and the temporal changes in AE ringing count correlation dimension and AE energy correlation dimension for coal-rock combinations of different strengths.

-

1.

The sentry function curve’s trend and the fracture process of coal-rock combinations are in line. The coal-rock combination samples’ AE ringing count and energy typically show a shift from calm to a surge throughout the loading procedure. This is reflected in the sentry function curve as a transition from a rise to a decline. The composite samples RCR-1, RCR-2, RCR-3, and RCR-4 show the first significant drop in the curve at 51.62%, 76.38%, 59.89%, and 43.31% of their peak stresses, respectively, marking the onset of damage. The inflection point, where the curve rises and then generally declines, can be used as the starting point to determine the active period of AE energy. The AE signals of the composite samples enter the active period at 83.17%, 94.79%, 75.71%, and 87.08% of their peak stresses, respectively.

-

2.

In sample RCR-1, there is no significant change during the early stages of loading. However, when the stress reaches 51.62% of the stress maximum, the coal initially fractures, and after failure, an “X”-shaped shear fracture zone is formed. In samples RCR-2, RCR-3, and RCR-4, cracks initiate in the soft rock and extend into the coal when the load reaches 76.38%, 59.89%, and 43.31% of the stress maximum, respectively. These samples mainly exhibit shear failure, and as the soft rock strength decreases, the failure mode of the coal rock mass gradually shifts to tensile-shear failure.

-

3.

In the lower-strength coal-rock combination samples RCR-2 and RCR-4, the post-peak released EF value is greater than the pre-peak stored strain energy ET. The end effect of the coal decreases with decreasing strength, indicating that as the axial stress increases, the samples undergo volume expansion and shear plane formation. In the higher-strength sample RCR-1, the coal-rock combination exhibits higher energy release and a more complex crack network. As compared to the lower strength samples RCR-2, RCR-3, and RCR-4, the intricacy of the fracture shape and the pace at which cracks propagate are much higher. This suggests that the material’s failure mode changes from brittle to ductile as strength decreases.

-

4.

Fractal features can be seen in the AE energy time series and the ringing count time series. The fitting coefficients of the AE energy correlation dimensions are all greater than 0.95, indicating good fractal characteristics with little difference between the two. The correlation dimension of the AE ringing count is often higher than that of AE energy during the loading process. On the other hand, the decline and variation of the AE energy correlation dimension are more susceptible to large-scale fracture occurrences. Compared to the composite sample RCR-1, the post-peak correlation dimensions of ringing count and AE energy in samples RCR-2, RCR-3, and RCR-4 are denser, indicating more crack development and wider expansion after the peak.

-

5.

Acoustic emission (AE) monitoring and AE fractal dimensions can reflect the evolution of microcrack initiation and propagation during the stability of coal-rock failure. The fractal correlation dimensions D of AE ringing count and energy rapidly and continuously decrease to a local minimum before the peak stress in coal-rock combination samples. At this point, the stress values of samples RCR-1, RCR-2, RCR-3, and RCR-4 are 94.59%, 93.64%, 98.28%, and 86.21%, correspondingly, which can serve as antecedent data to forecast composite sample failure.

In conclusion, our investigation into the fracturing behavior of coal-rock masses under hard-roof and soft-floor conditions reveals that soft-rock floor deformation is complex and has a considerable impact on coal mass deformation and fracture. This increases the potential of rock bursts and bottom drum disasters on roadways under these situations. As a result, catastrophe prevention and control procedures should be put in place for such highways’ roofs and floors.

This study primarily investigates the behavior of coal-rock masses with varying soft rock strengths under uniaxial compression in hard roof-soft floor conditions. Future research will utilize distributed optical fiber monitoring to observe the migration and deformation of the floor rock mass in situ. This will enable further exploration of the mechanical behavior and fracture characteristics of coal-rock masses under hard roof-soft floor conditions and facilitate the optimization of prevention and control measures for rockburst-prone roadways in such geological environments.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Change history

17 October 2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23321-3

References

Zhu, L. & Zhu, X. Economic prying effect of de-capacity and asset structure adjustment in the coal industry. Resour. Sci. 43 (2), 316–327 (2021).

Xie, H., Gao, F. & Ju, Y. Research and development of rock mechanics in deep ground engineering. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 34 (11), 2161–2178. https://doi.org/10.13722/j.cnki.jrme.2015.1369 (2015).

Yuan, L. et al. Research progress of coal and rock dynamic disasters and scientific and technological problems in China. J. China Coal Soc. 48 (5), 1825–1845. https://doi.org/10.13225/j.cnki.jccs.2023.0264 (2023).

Lu, S. et al. Damage-induced permeability model of coal and its application to gas predrainage in combination of soft coal and hard coal. Energy Sci. Eng. 7 (4), 1352–1367 (2019).

Zhang, J. et al. Study on failure characteristics and control of soft rock roadway floor. Coal Sci. Technol. 51 (3), 21–28. https://doi.org/10.13199/j.cnki.cst.2021-0968 (2023).

Ma, Q. et al. Progressive failure processes and mechanisms of disasters caused by interrelated failure of residual coal pillars and rock strata. Sci. Total Environ. 954, 176181 (2024).

Fu, Q. et al. Combined blasting for protection of gob-side roadway with thick and hard roof. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 1, 1 (2024).

Ma, Q. et al. Experimental study of loading system stiffness effects on mechanical characteristics and kinetic energy calculation of coal samples. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 1, 1–17 (2024).

Liu, J. et al. Dynamic multifractal characteristics of acoustic emission about composite coal-rock samples with different strength rock. Chaos Solitons Fractals 164, 164112725 (2022).

Yang, K. et al. Experimental investigation into interface effect and progressive instability of coal-rock combined sample. J. China Coal Soc. 45 (5), 1691–1700. https://doi.org/10.13225/j.cnki.jccs.DY20.0294 (2020).

Yu, W. et al. Mechanical properties and fracture evolution law of rock-coal-rock combinations. J. China Coal Soc. 47 (3), 1155–1167. https://doi.org/10.13225/j.cnki.jccs.xr21.1563 (2022).

Yu, Y. et al. Mechanical properties and damage constitutive model of coal with different water content based on energy principle. Coal Sci. Technol. 1, 1–14

Qin, Z. Tests on the dynamic failure rules of coal-rock composites. Acta Geodyn. Geomater. 16 (1), 39–54 (2019).

He, Y. et al. Mechanical properties and energy dissipation characteristics of coal–rock-like composite materials subjected to different rock–coal strength ratios. Nat. Resour. Res. 30 (3), 2179–2193 (2021).

Tan, Y. et al. Failure prediction from crack evolution and acoustic emission characteristics of coal-rock sandwich composite samples under uniaxial compression. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 81 (5), 200 (2022).

Chen, G. et al. Mechanical properties and failure mechanism of combined bodies with different coal-rock ratios and combinations. J. Min. Strata Control Eng. 3 (2), 84–94 (2021).

Zhao, G. et al. Failure mechanical behavior and energy evolution of coal and rock under cyclic loading and unloading. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 1, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.13722/j.cnki.jrme.2023.1082

Gong, C. et al. Acoustic emission (AE) source evolution and fractal features during creep failure of red sandstone. Rock. Soil. Mech. 42 (10), 2683–2695. https://doi.org/10.16285/j.rsm.2021.0012 (2021).

Saeedifar, M. & Zarouchas, D. Damage characterization of laminated composites using acoustic emission: A review. Compos. B Eng. 195, 108039. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compositesb.2020.108039 (2020).

Ma, Q. et al. Numerical study of mechanical properties and microcrack evolution of double-layer composite rock samples with fissures under uniaxial compression. Eng. Fract. Mech. 289, 109403 (2023).

Zhao, P. et al. Characterization of the time–space evolution of acoustic emissions from a coal-like material composite model and an analysis of the effect of the dip angle on the bursting tendency. Sustainability 16 (5), 1711. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16051711 (2024).

Du, K. et al. Experimental study on acoustic emission (AE) characteristics and crack classification during rock fracture in several basic lab tests. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 133, 104411. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2020.104411 (2020).

Moradian, Z., Einstein, H. H. & Ballivy, G. Detection of cracking levels in brittle rocks by parametric analysis of the acoustic emission (AE) signals. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 49 (3), 785–800. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-015-0775-1 (2016).

Dong, L. et al. Implications for rock instability precursors and principal stress direction from rock acoustic experiments. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 31 (5), 789–798. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmst.2021.06.006 (2021).

Li, L. et al. Experimental study on ultra-low friction effect and acoustic emission (AE) characteristics of coal-rock interface with different roughness. Chin. J. Theor. Appl. Mech. 56 (4), 1047–1056 (2024).

Tang, L. et al. Compressive failure characteristics of a coal–rock combination at different angles: experimental study and fractal analysis. Fractal Fract. 8 (4), 240. https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract8040240 (2024).

Yang, J. et al. Fracture evolution of fiber-reinforced backfill based on acoustic emission fractal dimension and b-value. Cem. Concr. Compos. 134, 104739. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2022.104739 (2022).

Li, C. et al. Study on energy evolution and fractal characteristics of cracked coal-rock-like combined body under impact loading. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 38 (11), 2231–2241. https://doi.org/10.13722/j.cnki.jrme.2019.0446 (2019). .(in china).

Zhao, K. et al. Acoustic emission fractal characteristics and mechanical damage mechanism of cemented paste backfill prepared with tantalum niobium mine tailings. Constr. Build. Mater. 258, 119720. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.119720 (2020).

Song, Y. et al. Study on damage evolution characteristics of sandstone with different saturations in freeze-thaw environment. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 40 (8), 1513–1524. https://doi.org/10.13722/j.cnki.jrme.2021.0089 (2021).

Wang, Q. Z. et al. Recalibration and clarification of the formula applied to the ISRM-suggested CCNBD sample for testing rock fracture toughness. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 46 (2), 303–313. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-012-0258-6 (2013).

Cai, X. et al. Effects of hole shape on mechanical behavior and fracturing mechanism of rock: implications for instability of underground openings. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 141, 105361. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tust.2023.105361 (2023).

Germanovich, L. N. & Dyskin, A. V. Fracture mechanisms and instability of openings in compression. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 37 (1–2), 263–284. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1365-1609(99)00105-7 (2000).

Qin, Y. et al. Experimental study on the effects of geometric parameters of filled fractures on the mechanical properties and crack propagation mechanisms of rock masses. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 56 (4), 2697–2716. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-022-03198-8 (2023).

Ma, Q. et al. Effect of coal thicknesses on energy evolution characteristics of roof rock-coal-floor rock sandwich composite structure and its damage constitutive model. Compos. B Eng. 198, 108086. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compositesb.2020.108086 (2020).

Li, F. et al. Effects of combination mode on mechanical properties of bi-material samples consisting of rock and coal. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 19, 2156–2170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmrt.2022.05.174 (2022).

Zhao, P. et al. Coal thickness effect on mechanics and energy characteristics of coal-rock combinations model. J. Min. Saf. Eng. 37 (5), 1067–1076. https://doi.org/10.13545/j.cnki.jmse.2020.05.025 (2020).

Vidya Sagar, R. & Basu, D. J. Damage assessment of reinforced concrete structures under elevated-amplitude cyclic loading using sentry values based on acoustic emission testing. Nondestruct. Test. Eval. 38 (4), 612–630. https://doi.org/10.1080/10589759.2022.2144852 (2023).

Zhu, Z. et al. Experimental study on the influence of width-height ratio on coal pillar type rock burst. J. China Coal Soc. 49 (3), 1303–1317. https://doi.org/10.13225/j.cnki.jccs.xr23.1396 (2024).

Szeląg, M. Fractal characterization of thermal cracking patterns and fracture zone in low-alkali cement matrix modified with microsilica. Cem. Concr. Compos. 114, 103732. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2020.103732 (2020).

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 52174116).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Jiajun Li: Methodology, Writing. Yin Zhang: Supervision and Editing. Chenchen Yang: Editing. Jiaqi Lin: Editing. Yu Zhou: Methodology. Chunlin Li: Data Curation. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this Article was revised: The original version of this Article contained an error in Figure 4, where the captions for panels (b), (c) and (d) were duplications of the caption of panel (a). Full information regarding the corrections made can be found in the correction for this Article.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, J., Zhang, Y., Yang, C. et al. The study of mechanical properties and fracture evolution of coal-rock masses under hard roof-soft floor conditions. Sci Rep 15, 3612 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86839-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86839-6