Abstract

This study utilized grab and strip testing methods to examine the relationship between three weave structures—plain, twill, and satin—and their tensile strengths in both warp and weft directions. In addition, microplastic fiber (MPF) emissions from these three weave structures were quantified at different states of the laundry process using filtration and microscopy. The grab and strip tests revealed that twill- and satin-woven fabrics exhibited higher tensile strengths in the warp direction compared to the weft orientation. In contrast, the plain weave structure showed similar tensile strengths in both warp and weft directions. During laundry in the washing machine, MPF emissions in the first drainage were the highest regardless of the weave structure. Moreover, the satin weave pattern released the most MPFs among the three common weave structures at 5054 particles/L. This weave pattern also had the weakest tensile strength of 3.1 N/cm2 in the weft direction of the three weave structures evaluated. The results demonstrated a strong inverse correlation between higher tensile strengths in the weaker direction (warp or weft) and MPF emissions. Among the weave structures investigated, the twill pattern had the lowest MPF emission, followed by plain weave, with the satin-woven fabric emitting the highest levels.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, microplastics (MPs)—small plastic particles less than five millimeters in diameter—have emerged as persistent and pervasive pollutants in freshwater and marine ecosystems. Non-biodegradable by nature, MPs can persist in the environment for thousands of years and spread easily via wind and water due to their light weight and fine size1. These fine-sized plastic particles could be generated even through everyday activities like washing of plastic and non-stick kitchen utensils and laundry of textiles made of plastic fibers1,2.

The detrimental impacts of MPs on marine organisms, ranging from planktons to large mammals, have been highlighted by many authors. These impacts include direct physical injuries, exposure to toxic organic compounds like Bisphenol A (BPA), developmental abnormalities, and even death3. Furthermore, inorganic pollutants like heavy metals in seawater have been reported to adsorb onto MPs due to their hydrophobic surface properties readily4. This phenomenon enables MPs to carry and concentrate hazardous substances within the organisms that consume them. To make matters worse, MPs have been detected in the digestive system of fish—an important protein source for humans—raising concerns about their entry into the human food chain5. Xu et al.6, for example, reported 13 types of MPs, including polyethylene (PE), polypropylene (PP), and polyethylene-co-polypropylene (EPR), in blood, cancer, and paracarcinoma samples of cancer patients. Similarly, Zhu et al.7 detected MPs in human placenta samples using laser direct infrared spectroscopy, reporting relative abundances ranging from 0.28 to 9.55 particles/g. These authors also identified polyvinyl chloride (PVC, 43.3%), PP (14.6%), and polybutylene succinate (PBS, 10.90%) as the dominant polymers in the samples, with sizes ranging from 20 to 310 μm.

MPs originate from both primary and secondary sources. Primary MPs are intentionally manufactured on macro to microscopic scale for use in products like toothpastes, facial scrubs, and industrial abrasives. In contrast, secondary MPs are inadvertently formed when larger plastics weather and degrade in the environment through ultraviolet (UV) irradiation, physical abrasion, and biologically mediated disintegration8. Among secondary MPs, microplastic fibers (MPFs) are one of the most problematic because they are readily produced when textiles made of synthetic fibers are machine-washed9. Exacerbating their pollution potential is the inherent ability of MPFs, like other MPs, to concentrate hazardous pollutants whose concentrations in the environment are usually low and carry them long distances through the action of wind and water10. Because of their profound impacts on freshwater and marine ecosystems, the reduction of MP emissions into major water bodies is a key component of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) #14, "Life Below Water".

Polyester, also known as polyethylene terephthalate (PET), is a versatile plastic widely used not only in containers and packaging but also as a synthetic fiber in the textile industry. Its popularity stems from its durability, resistance to extension and contractions, and rapid drying qualities. These attributes, combined with low production costs, have made polyester an indispensable material not only in the global fashion and clothing industry but also in home furnishings, construction, automotive parts, electrical insulation, and food packaging11. However, the extensive adoption of polyester raises serious environmental concerns, particularly due to the absence of sustainable practices in its production, utilization, and disposal—a key focus of SDG #12. “Responsible Consumption and Production”.

Figure 1 is a schematic diagram illustrating the environmental impacts of the polyester textile industry across its lifecycle. In the early stages of textile manufacturing, raw materials for polyester production (e.g., crude oil and antimony trioxide (Sb2O3)) and fossil fuels are mined and extracted, respectively8. The mining and extraction of these raw materials and fossil fuels contribute to not only the depletion of finite resources but also greenhouse gas emissions12. Once woven into fabrics, polyester releases MPFs during washing, contributing to marine pollution13. Finally, disposal of polyester textiles is problematic because they are non-biodegradable and contain non-biodegradable dyes that could leach into soil and water systems14.

The textile industry is a significant consumer of natural resources and a major source of environmental pollution, particularly through processes like dyeing and finishing. Untreated wastewater from this sector, for example, contains around 72 toxic compounds, including heavy metals, azo dyes, and formaldehyde, which pose serious risks to aquatic life and human health15,16. In addition, the industry’s focus on fast fashion—a business model emphasizing the rapid design, production, and distribution of clothing and footwear to match current trends—has exacerbated these environmental challenges17. Although fast fashion drives the growth of the textile manufacturing sector, it also leads to increased textile waste, more widespread water pollution, and more extensive carbon emissions17.

A major contributor to MP pollution, the textile industry releases MPFs into the environment, primarily through the laundry of synthetic textiles18. During laundry, especially in washing machines, textiles are continuously subjected to mechanical actions like bending, stretching, and abrasion, particularly during the washing and rinsing cycles. Over time and with repetitive laundry, mechanical stress accumulates on the fabric, weakening fibers and promoting the release of MPFs. The extent of this weakening effect has been reported to depend on washing parameters, including the cycle intensity of the washing machine, fabric type, and textile weight19,20. In addition, inherent properties of the fabric, like woven structure and tensile strength, have been linked to the extent of MPF emissions21. Tighter weaves, for example, reduce the shedding of fibers because these woven structures hold the yarns more securely, whereas looser weaves facilitate easier breakage and shedding of fibers22. Weaving patterns also directly influence the tensile strength of the fabric, thereby impacting its overall performance when subject to tension23. Tensile strength is the greatest strain a fabric can withstand due to tension or stretching force before breakdown. The woven structure and how the fibers interact are essential in determining the tensile strength of textiles. For instance, the interlacing of yarns within these structures facilitates improved tension distribution throughout the fabric, resulting in better strength and durability24,25. The tensile strength of fabrics also depends on weave density and the type of textile material; that is, tensile force resistance is enhanced in fabrics woven with high-density patterns and high-strength textile materials, such as polyester and nylon26.

Understanding the relationship between tensile strength and weave structure is crucial for not only improving the overall quality of polyester textiles but also augmenting fabric durability through design optimization. The weave structure of polyester fabrics is created by the methodical interlacing of strands, commonly done in a perpendicular arrangement11. For conventional applications, the most widely used weave structures are plain, twill, and satin8. Among these three, those with more floating weave patterns like satin and 3:1 twill have been reported to emit higher MPFs27. In previous work of the authors, for example, it was observed that twill weave had lower MPF emissions than satin weave, which was attributed to higher mechanical properties of the former than the latter21. However, the relationship between MPF emissions and the mechanical properties of fabrics was only implied in this previous work because the authors did not directly measure the tensile strengths of the fabrics evaluated. Very few studies in the literature have also assessed how the weave structure and mechanical properties of synthetic fabrics affect MPF emissions during laundry in washing machines.

In this study, a detailed investigation of the effects of weave structures and tensile strength on MPF emissions from polyester fabric during laundry in washing machines was conducted. Specifically, this work aims to (i) characterize various woven structures, (ii) assess the impacts of woven structures on the tensile strengths of polyester fabrics, (iii) analyze and quantify MPF released during laundry, and (iv) understand the interrelationships between woven structure, tensile strength, and MPF emissions. The results of this study have the potential to guide manufacturers in optimizing their production processes to enhance fabric durability, thereby decreasing the frequency of replacements. Furthermore, this work offers valuable insights for policymakers to develop regulations addressing MPF discharges from textiles that contribute to broader environmental protection and sustainability goals.

Materials and methods

The experimental procedures employed in this study are outlined in Fig. 2 and involved several key steps: sample preparation, textile washing using a top-loading washing machine, filtration of drainage through a 2.7 μm pore filter (with a diameter of 47 mm), collection of MPFs, Fourier transform infrared micro‐spectroscopy (μ‐FTIR) image capture of filters, and manual counting of MPFs for quantification and calculation. Previous studies have highlighted significant variability in MPF quantification across different washing machine laundry steps. These inconsistencies are largely attributed to variations in identification methodologies and research approaches. Based on our review of related literature, visual inspection with microscopes remains the most widely used method for identifying and quantifying MPFs due to its simplicity, reliability, and widespread accessibility.

Sample characterization

Scanning electron microscopy observations

This study examined 100% polyester textiles featuring three distinct woven patterns: plain (1:1), twill (2:2), and satin (3:1). All textile samples were sourced from the same factory in Bangkok, Thailand, ensuring consistency in production. The polyester fibers in all three weave patterns share the same characteristics, as they originated from a single supplier. To maintain consistency in sample dimensions and accurately represent commercially available apparel, each textile sample was precisely cut into 50 × 50 cm pieces using scissors. The edges were then secured with a hemstitch to prevent fraying and ensure durability during testing21.

Tensile strength measurements

The tensile strengths of samples were determined using both the grab and strip methods following ASTM D 503428 and ASTM D 503529, respectively (Fig. 3). The grab test involved securing a sample of a specified width and stretching it until breakage. This process allows for measuring several parameters, including breaking strength and elongation. Meanwhile, the strip test required cutting a narrow strip of fabric and applying tensile forces until the fabric broke, allowing maximum force and elongation to be determined.

In woven fabrics, the warp refers to the lengthwise strands or threads held under tension on a frame or loom, forming the foundation of the fabric. Meanwhile, the yarn woven horizontally over and beneath the warp yarn is called the weft. To resist the tension exerted throughout the weaving process, the warp fibers are typically stronger than the weft fibers. Five pieces of 100 × 150 mm fabrics were prepared for the grab test, with measurements taken in both the warp and weft directions (Fig. 4). Furthermore, eight textile specimens measuring 50 × 200 mm were created in preparation for the strip test. The samples with a length of 75 mm were pulled at a speed of 300 mm/min until breakage using a multipurpose strength tester (Instron 5566, Instron®, Norwood, MA, USA).

Laundry experiments

Washing step

A 7 kg top-loading washing machine, equipped with a 5-L container, was utilized in this study to elucidate the identified critical factors influencing MPF emissions. The washing machine featured eight operational modes, including “Quick”, “Wash”, “Normal”, “Rinse”, “Soak”, “Spin”, “Delicate”, and “Tub Dry”. For the washing experiments, the “Normal” laundry mode was selected, consisting of a 15-min washing phase, a 5-min rinsing phase, and a 3-min draining phase. The laundry wastewater from the three washing phases was collected in a container and then filtered for further analysis. Each experimental run used 1.0 kg of textile samples, 33 L of water, and 35 mL of a commercial liquid detergent, chosen based on its widespread use in Thailand.

Draining of washed water and microplastic fiber collection

Laundry wastewater was collected at the completion of each draining stage, using a consistent duration to transfer laundry wastewater from the drainage tube into a 10 L container. To ensure uniform distribution of MPFs, the laundry wastewater was agitated continuously during filtration process. The filtration setup used in this work was based on Cai et al.30 and Wang et al.31, who recommended employing a vacuum pump and filter paper with a pore size of 2.7 μm and a diameter of 47 mm (Whatman GF/D glass microfiber filters, Hangzhou, China). A filtration volume of 1L was selected to reduce the likelihood of overlapping MPs appearing on filters32. After filtration, each glass filter was individually placed in a glass Petri dish, covered, and dried in an oven preheated to 40 °C for 24 h. To prevent cross-contamination from previous experiments, all laboratory materials were thoroughly rinsed three times with purified water before use. A strict and consistent protocol was followed throughout the study to eliminate the risk of MPF accumulation in laboratory equipment, ensuring reliable and accurate results.

Fourier transform infrared micro-spectroscopy analysis

To quantify MPF emissions, multiple photomicrographs of the glass filters from each experiment were systematically captured using a Fourier transform infrared micro-spectroscopy (μ-FTIR) (LUMOS II, Bruker Optics Inc., Ettlingen, Germany). The photomicrographs were taken along four directional lines (L1, L2, L3, and L4) as depicted in Fig. 5. MPFs measuring 1.50 × 1.42 mm were manually counted from 150–160 representative photomicrographs obtained with the microscope. The number of MPFs identified in each image was then used to calculate the MPF concentration in particles per liter (particles/L).

Results and discussion

Weave structures and tensile strength of polyester fabric

Tensile strength is an important mechanical property of woven textiles because it directly correlates with the durability of fabrics23. Figure 6 presents the tensile strengths of polyester fabrics with plain, twill, and satin weave structures measured using the grab and strip tests along the warp (Fig. 6a-1 and 6b-1) and weft (Fig. 6a-2 and 6b-2) directions.

For plain weave textiles, tensile strength along the warp direction was measured at 3.4 N/cm2, slightly lower than the 3.7 N/cm2 recorded for the weft direction (Fig. 6a-1 and 6a-2). These results were consistent with the tensile strength determined through the strip test; that is, the tensile strength in the warp direction (6.4 N/cm2) was slightly lower than the weft direction (7.4 N/cm2) (Fig. 6b-1 and 6b-2). This relatively uniform tensile strength distribution in the plain weave pattern’s warp and weft directions could be attributed to the evenly distributed yarn interlacing and consistent interlacing coefficient. In contrast, the twill and satin weave structures exhibited a different trend. Tensile strengths measured via the grab testing method were higher in the warp direction (5.4 N/cm2 for twill and 6.8 N/cm2 for satin) than in the weft direction (4.4 N/cm2 for twill and 3.1 N/cm2 for satin). The strip test results also reflected this trend; that is, both twill and satin weave structures demonstrated higher tensile strengths along the warp direction (10.3 N/cm2 for twill and 13.1 N/cm2 for satin) than the weft direction (9.2 N/cm2 for twill and 6.2 N/cm2 for satin). Compared to plain weave, the observed decrease in tensile strength in twill and satin weave structures, particularly in the weft direction, aligned with findings from previous studies. This lower tensile strength could be attributed to the larger number of floats and fewer binding points in these structures, which weaken the ability of fabrics to withstand tension23,33,34.

Among the three weave patterns, the satin weave exhibited the highest tensile strength in the warp direction across both the grab and strip tests, followed by twill and plain weave patterns. However, this order was reversed in the weft direction, where twill had the highest tensile strength, followed by plain and satin weave structures. Based on these results, the tensile strengths of fabrics strongly depend on their weave structures. In theory, textiles with higher tensile strengths have better resistance against mechanically induced stresses encountered during laundry in washing machines while those with lower tensile strengths are more susceptible to damage and MPF emissions35. Consequently, a detailed examination of the three common weave structures with lower tensile strengths along both the warp and weft directions were conducted.

Effects of weave structures on microplastic fiber emissions during laundry process

The quantities of MPF emitted by the three common weave structures—plain, twill, and satin—during the washing experiments are presented in Fig. 7. The results indicate that the first drainage consistently exhibited the highest MPF emissions across all weave structures. As illustrated in Fig. 7a, plain-woven fabrics had the highest emission of MPFs during the first drainage at 3189 particles/L, followed by twill and satin weave structures at 2962 and 2948 particles/L, respectively. It is interesting to note that these findings do not establish a clear hierarchy of MPF emissions during the initial drainage of laundry in washing machines. This ambiguity arises from the observed overlap in standard deviations (SD) during the statistical analysis of the results for the three weave structures. However, the degree of SD overlap decreased significantly and was no longer evident in the second drainage of the laundry washing cycle. In this phase, it was found that satin-woven fabric exhibited the highest MPF emission at 1180 particles/L, followed by plain weave pattern (1056 particles/L) and twill weave structure (796 particles/L). Similarly, the satin-woven fabric had the highest emission of MPFs (926 particles/L) in the final drainage of the laundry washing cycle. Also, both twill (742 particles/L) and plain (602 particles/L) weave structures showed lower MPF emissions, but the order between these two weave patterns in terms of MPF emission could not be established due to the observed overlap in SD.

The significantly higher MPF emissions during the first drainage compared to the second and third drainage cycles during laundry in washing machines are consistent with previous findings of other authors. Napper and Thompson22, for example, observed a decrease in MPF emissions over subsequent drainage cycles, with minimal differences between semifinal and final cycles for polyester textiles. This trend was also reported by Pirc et al.36, who noted a substantial initial surge in MPF emission for polyester fleece blankets in the first drainage, followed by stabilization in subsequent drainage cycles. According to Kelly et al.37, the first drainage comes from a delicate cycle characterized by a high water-volume ratio relative to textile weight and a low agitation rate, which could lead to higher overall hydrodynamic pressure exerted on the textile, increasing MPF emissions. As water traverses through and flows over the fabric, each MPF particle undergoes significant viscous forces that may function to dislodge small fibers from the primary textile weave. Nonetheless, in our study, washing parameters associated with these mechanisms, such as water volume to textile weight ratio, detergent dosage, textile type, and washing time duration, were strictly controlled. Consequently, it is suggested that the initial surge in fiber release may be attributed to the liberation of loose, unbroken fiber debris from the yarn interior during the first drainage of the laundry washing cycle. This phenomenon is consistent with the noteworthy property of polyester textiles, which readily adheres to bubbles due to their hydrophobic nature21,38. As a result, the first drainage cycle, characterized by a higher concentration of detergent and bubbles, could enhance the emission of MPFs. In contrast, the second and third drainage cycles, with less detergent concentration and soap bubble density, exhibited substantially lower MPF emissions.

Over the entire laundry cycle in washing machines, including the three stages of wastewater drainage, the highest MPF emissions were observed in the satin weave structure, reaching 5054 particles/L. This was followed by the plain weave pattern at 4847 particles/L while the twill-woven fabric exhibited the lowest emission at 4500 particles/L (Fig. 7b). These emission levels correspond closely to the tensile strength of each weave structure, with weaker tensile strength associated with higher MPF emissions, a relationship explored in more detail in the next section.

Relationship between tensile strength and microplastic fiber emission

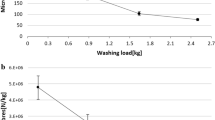

The weave structure of fabrics is a crucial parameter directly influencing the tensile strength of woven textiles. As noted in the previous subsection, a strong relationship was observed between the weave structure and tensile strength of polyester fabrics in both the warp and weft directions. However, there is a lack of evidence regarding the relationship between the tensile strength of textiles and their MPF emissions. Figure 8 illustrates the correlation between MPF release, weave structure, and tensile strength using both the grab (Fig. 8a) and strip (Fig. 8b) testing methods along the identified weakest direction (warp or weft).

The results indicate that polyester textiles with the satin weave pattern exhibited the highest MPF emissions at 5054 particles/L, followed by plain weave (4847 particles/L) and twill weave (4500 particles/L) structures. These findings also aligned with the observed decreasing order of tensile strengths of the three weave structures measured by the grab test in the weft direction: satin weave (3.1 N/cm2) < plain weave (3.4 N/cm2) < twill weave (4.4 N/cm2). Strong negative correlations were also observed between MPF emissions and the weakest tensile strength for both the grab (R2 = 0.97) and the strip (R2 = 0.91) testing methods. Although the weakest tensile strength determined by the strip testing method (9.2 N/cm2, 6.4 N/cm2, and 6.2 N/cm2 for twill, plain, and satin weave structures, respectively) were higher than those measured by the grab test, the relationship between MPF emissions and the weakest tensile strength remained consistent. Comparing the two test methods for tensile strength determination, the grab test was more reliable than the strip test. This could be attributed to the fact that specimens for the grab test were more straightforward to prepare, and the testing conditions closely mimic the load application on textiles in actual use39. Based on these results, MPF emissions could be minimized by adopting the twill weave structure for polyester textiles. The higher tensile strength of the twill weave structure enabled it to withstand mechanical stresses during laundry better, reducing fiber breakage and subsequent MPF emissions.

Conclusions

This study investigated the influence of weave structures and tensile strength of polyester textiles on MPF emissions during laundry in washing machines. The key findings of this work are summarized as follows:

-

The twill and satin weave structures exhibited higher tensile strengths in the warp direction compared with the weft direction by factors of 1.15 and 2.15, respectively.

-

The plain weave structure demonstrated similar tensile strengths in both the warp and weft directions, indicating uniform mechanical properties.

-

MPF emissions from polyester textiles during laundry in washing machines were significantly higher during the first draining stage of the washing cycle compared to subsequent draining cycles, with emissions around 2.5–3.7 times higher than the second drainage and 3.2–5.2 times higher than the third drainage.

-

Among the three weave structures, satin-woven textiles produced the highest MPF emissions, while twill-woven fabrics exhibited the lowest emissions.

-

MPF emissions decreased with increasing weakest tensile strength, indicating a linear trend.

-

The grab testing method was more precise (R2 = 0.97) than the strip testing method (R2 = 0.91) for evaluating the relationship between weakest tensile strength and MPF emissions.

-

The results highlighted the important role played by the weave structure in determining both the mechanical properties and MPF emissions of synthetic fabrics.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Liu, Y. et al. A systematic review of microplastics emissions in kitchens: Understanding the links with diseases in daily life. Environ. Int. 188, 108740. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2024.108740 (2024).

Campos, A. R. A. et al. Polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) microplastics affect angiogenesis and central nervous system (CNS) development of duck embryo. Emerg. Contam. 11(1), 100433. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emcon.2024.100433 (2025).

Rochman, C., Hoh, E., Kurobe, T. & The, S. J. Ingested plastic transfers hazardous chemicals to fish and induces hepatic stress. Sci. Rep. 3, 3263. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep03263 (2013).

Xu, J., Wang, L. & Sun, H. Adsorption of neutral organic compounds on polar and nonpolar microplastics: Prediction and insight into mechanisms based on pp-LFERs. J. Hazard. Mater. 408, 124857. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.124857 (2021).

Mamun, A. A., Prasetya, T. A. E., Dewi, I. R. & Ahmad, M. Microplastics in human food chains: Food becoming a threat to health safety. Sci. Total Environ. 858(Part 1), 159834. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.159834 (2023).

Xu, H. et al. Detection and analysis of microplastics in tissues and blood of human cervical cancer patients. Environ. Res. 259, 119498. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2024.119498 (2024).

Zhu, L. et al. Identification of microplastics in human placenta using laser direct infrared spectroscopy. Sci. Total Environ. 856, 159060. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.159060 (2023).

Andrady, A. L. Microplastics in the marine environment. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 62(8), 1596–1605. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2011.05.030 (2011).

Browne, M. A. et al. Accumulation of microplastic on shorelines worldwide: sources and sinks. Environ. Sci. Technol. 45(21), 9175–9179. https://doi.org/10.1021/es201811s (2011).

Teuten, E. L., Rowland, S. J., Galloway, T. S. & Thompson, R. C. Potential for plastics to transport hydrophobic contaminants. Environ. Sci. Technol. 43(16), 7759–7764. https://doi.org/10.1021/es071737s (2009).

Blackburn, R. S. Sustainable textiles: Life cycle and environmental impact (Woodhead Publishing, 2009).

Sandin, G., Roos, S. & Johansson, M. Environmental impact of textile fibres – what we know and what we don’t know: Fiber bible part 2. Digitala Vetenskapliga Arkivet (2019).

Thompson, R. C. Microplastics in the marine environment: sources, consequences and solutions. Marine Anthropogenic Litter. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-16510-3_7 (2015).

Labayen, J., Labayen, I. & Yuan, Q. A review on textile recycling practices and challenges. Textiles. 2, 174–188. https://doi.org/10.3390/textiles2010010 (2022).

Al-Tohamy, R. et al. A critical review on the treatment of dye-containing wastewater: Ecotoxicological and health concerns of textile dyes and possible remediation approaches for environmental safety. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 231, 113160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoenv.2021.113160 (2022).

Hasanuzzaman, C. B. Indian textile industry and its impact on the environment and health: A review. Int. J. Inf. Syst. Serv. Sect. 8(4), 33–46. https://doi.org/10.4018/IJISSS.2016100103 (2016).

Bick, R., Halsey, E. & Ekenga, C. C. The global environmental injustice of fast fashion. Environ. Health. 17(1), 92. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12940-018-0433-7 (2018).

Boucher, J. & Friot, D. Primary microplastics in the oceans: A global evaluation of sources. Int. Union Conserv. Nat. https://doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.CH.2017.01.en (2017).

Tedesco, M. C., Fisher, R. M. & Stuetz, R. M. Emission of fibres from textiles: A critical and systematic review of mechanisms of release during machine washing. Sci. Total Environ. 955, 177090. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.177090 (2024).

Han, J., McQueen, R. H. & Batcheller, J. C. From fabric to fallout: A systematic review of the impact of textile parameters on fibre fragment release. Textiles. 4(4), 459–492. https://doi.org/10.3390/textiles4040027 (2024).

Julapong, P. et al. The Influence of textile type, textile weight, and detergent dosage on microfiber emissions from top-loading washing machines. Toxics. 12(3), 210. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics12030210 (2024).

Napper, I. E. & Thompson, R. C. Release of synthetic microplastic plastic fibres from domestic washing machines: Effects of fabric type and washing conditions. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 112(1–2), 39–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2016.09.025 (2016).

Jahan, I. Effect of fabric structure on the mechanical properties of woven fabrics. Adv. Res. Text. Eng. 2(2), 1018. https://doi.org/10.26420/advrestexteng.2017.1018 (2016).

Peirce, F. T. The geometry of cloth structure. J. Text. Inst. 40(1), 11–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/19447014908664605 (2016).

Ghosh, S. et al. Carbon nanostructures based mechanically robust conducting cotton fabric for improved electromagnetic interference shielding. Fibers Polym. 19, 1064–1073. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12221-018-7995-4 (2018).

Patti, A. & Acierno, D. Materials, weaving parameters, and tensile responses of woven textiles. Macromol. 3, 665–680. https://doi.org/10.3390/macromol3030037 (2023).

Periyasamy, A. P. & Tehrani-Bagha, A. A review on microplastic emission from textile materials and its reduction techniques. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 199, 109901 (2022).

ASTM Standard D5034. Standard Test Method for Breaking Strength and Elongation of Textile Fabrics (Grab Test). ASTM International, West Conshohocken, PA, https://doi.org/10.1520/D5034-21, www.astm.org (2021).

ASTM Standard D5035. Standard Test Method for Breaking Force and Elongation of Textile Fabrics (Strip Method). ASTM International, West Conshohocken, PA, https://doi.org/10.1520/D5035-11R19, www.astm.org (2019).

Cai, Y. et al. Systematic study of microplastic fiber release from 12 different polyester textiles during washing. Environ. Sci. Technol. 54(4847–4855), 2020. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.9b07395 (2020).

Wang, C. et al. Microplastic fiber release by laundry: A comparative study of handwashing and machine-washing. ACS ES&T Water. 3, 147–155. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsestwater.2c00462 (2023).

Hernandez, E., Nowack, B. & Mitrano, D. M. Polyester textiles as a source of microplastics from households: A mechanistic study to understand microfiber release during washing. Environ. Sci. Technol. 51, 7036–7046. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.7b01750 (2017).

Asaduzzaman, M. et al. Effect of weave type variation on tensile and tearing strength of woven fabric. Technium Romanian J. Appl. Sci. Technol. 2(6), 35–40. https://doi.org/10.47577/technium.v2i6.1409 (2020).

Ferdous, N., Rahman, M. S., Kabir, R. B. & Ahmed, A. E. A comparative study on tensile strength of different weave structures. Int. J. Sci. Res. Eng. Technol 3, 1307–1313. https://doi.org/10.47577/technium.v2i6.1409 (2014).

Wakeham, H. & Spicer, N. The strength and weakness of cotton fibers. Text. Res. J. 21(4), 187–194. https://doi.org/10.1177/004051755102100401 (1951).

Pirc, U., Vidmar, M., Mozer, A. & Kržan, A. Emissions of microplastic fibers from microfiber fleece during domestic washing. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 23, 22206–22211. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-016-7703-0 (2016).

Kelly, M. R., Lant, N. J., Kurr, M. & Burgess, J. G. Importance of water-volume on the release of microplastic fibers from laundry. Environ. Sci. Technol. 53, 11735–11744. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.9b03022 (2019).

Julapong, P. et al. Agglomeration–flotation of microplastics using kerosene as bridging liquid for particle size enlargement. Sustainability. 14, 15584. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142315584 (2022).

Wu, J. & Pan, N. Grab and strip tensile strengths for woven fabrics: An experimental verification. Text. Res. J. 75(11), 789–796. https://doi.org/10.1177/0040517505057525 (2005).

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the members of the Department of Mining and Petroleum Engineering and Department of Environmental and Sustainable Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, Chulalongkorn University, for their support to this project. The valuable inputs of the editors and anonymous reviewers to this paper are also greatly appreciated by the authors.

Funding

This research is funded by the Thailand Science Research and Innovation Fund, Chulalongkorn University (DIS66210021).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

O.J.: conceptualization, methodology, writing—original draft, writing—review & editing, visualization. P.J.: methodology, validation, formal analysis, data curation, writing—original draft, writing—review & editing, visualization. P.S.: formal analysis, data curation, writing—review & editing, visualization, project administration. T.M.: validation, formal analysis, investigation, writing—review & editing. D.J.: contributed to writing—review & editing. C.B.T.: writing—review & editing. T.P.: conceptualization, methodology, resources, writing—original draft, writing—review & editing, supervision, funding acquisition.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Juntarasakul, O., Julapong, P., Srichonphaisarn, P. et al. Weave structures of polyester fabric affect the tensile strength and microplastic fiber emission during the laundry process. Sci Rep 15, 2272 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86866-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86866-3