Abstract

This study aims to assess the clinical efficacy and feasibility of the Perclose ProGlide Suture-Mediated Closure System (Abbott Vascular, Redwood City, CA, USA) for transbrachial access. A total of 100 patients from July 2020 to December 2023 were included in this retrospective study. Among them, 40 patients underwent ProGlide-guided suture closure following brachial artery (BA) puncture, while 60 patients received traditional manual compression. After successful ultrasound-guided puncture of the BA, a sheath of appropriate diameter (5–7F) was inserted. The Perclose ProGlide system was utilized in patients requiring ipsilateral upper limb intravenous infusion or dynamic blood pressure monitoring. All other patients underwent standard manual compression. No significant differences in major complications, including hematoma, pseudoaneurysm, or active bleeding, were observed between the two groups (P = 0.407). Additionally, there were no reported cases of arterial occlusion, ischemia, or venous thrombosis in either cohort. In the manual compression group, three patients required reintervention due to bleeding or hematoma, whereas no such incidents occurred in the ProGlide group (P = 0.151). Two patients in the manual compression group reported long-term numbness around the puncture site, while no similar neurological dysfunction was observed in the ProGlide group (P = 0.243). Although selection bias was present in this retrospective study, the Perclose ProGlide system presents a beneficial closure method for patients undergoing transbrachial access.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With advancements in interventional techniques and materials, endovascular therapy has become increasingly prevalent in managing vascular diseases. Selecting the appropriate puncture access is the foundational step of interventional treatment and critically determines the success of subsequent procedures1. For non-cardiac interventions, the femoral artery is the most commonly utilized access point. However, in situations where conventional approaches are unsuitable—such as in cases of aortoiliac artery occlusion, severe calcification of the common femoral artery, significant iliac artery tortuosity, or when multiple access points are required (e.g., aortic dissection and subclavian artery occlusion)—the brachial artery (BA) is often employed as a preferred alternative2,3,4. BA access offers several advantages, including suitability for day-case procedures or ambulatory surgeries due to its minimally invasive nature, which eliminates the need for prolonged bed rest. Additionally, transbrachial access significantly reduces the risk of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) associated with extended immobility, enhancing the comfort and freedom of hospitalized patients, particularly in cases requiring catheter-directed thrombolysis5. Consequently, the use of BA access has become increasingly widespread. Ultrasonography-guided BA puncture has further improved procedural success rates while reducing postoperative complications.

In recent years, however, the BA approach has been associated with higher morbidity compared to traditional femoral access. Challenges unique to percutaneous puncture and closure at the elbow include the lack of a stable bony support, proximity to veins and nerves, vessel mobility, and the use of heparin6. Puncture-related complications, often correlated with larger sheath sizes, have been reported across several studies. Hemorrhage remains the most common complication of brachial punctures, with manual compression being the traditionally preferred method for achieving hemostasis7,8.

Manual compression, widely regarded as the gold standard for most percutaneous BA procedures, requires sufficient pressure and extended application time to prevent hematoma formation9. However, this approach has several drawbacks, including prolonged procedure time, increased nursing costs, patient discomfort, swelling, potential hematoma, pseudoaneurysm, and delayed healing of the arterial incision site9,10. These challenges complicate and increase the risks associated with repeated punctures.

The Perclose ProGlide Suture-Mediated Closure System (Abbott Vascular) represents a well-established, suture-based vascular closure device (VCD) commonly used for femoral access. This device facilitates one-stage hemostasis through effective suture-mediated closure, even in patients on anticoagulant therapy11. By reducing scar tissue formation, it also simplifies repeated access. Although the Perclose ProGlide system has been applied in transbrachial approaches, its feasibility and applicability remain subjects of debate8. This study aimed to evaluate the comparative performance of the Perclose VCD strategy against traditional manual compression in transbrachial approaches, focusing on access-related complications and overall clinical outcomes.

Materials and methods

Patients

This retrospective study analyzed 100 patients who underwent transbrachial interventions at our hospital between July 2020 and December 2023. The sample size was determined based on the number of cases treated in the region during the study period. Procedures included coronary angiography, coronary stent implantation, endovascular exclusion of thoracic aortic dissection, renal artery stent implantation, vascular malformation embolization, subclavian artery balloon dilation, and cerebral angiography.

While the radial artery is the conventional access route for coronary interventional procedures, radial artery puncture was replaced by BA puncture in selected patients in this study due to the difficulty or failure of radial access. For non-coronary interventions, where the femoral artery is the standard access point, BA puncture was chosen in specific clinical scenarios. These included cases such as thoracic aortic dissection requiring additional stenting to reconstruct the left subclavian artery or situations necessitating supplemental punctures for intraoperative angiography.

Patients with a BA diameter of ≥ 4 mm, as determined by ultrasound, were included in the study. Ultrasound guidance was employed during the procedure to ensure accurate puncture and to avoid areas of anterior wall calcification in the BA. Patients undergoing BA puncture were divided into two groups:

-

1.

Perclose ProGlide Group: Patients requiring ipsilateral upper limb intravenous infusion or dynamic blood pressure monitoring were treated using the Perclose ProGlide Suture-Mediated Closure System (Abbott Vascular, Redwood City, CA, USA).

-

2.

Manual Compression Group: All other patients were managed with standard manual compression techniques.

Post-procedure, all patients underwent clinical physical examinations to assess the condition of the radial artery pulse. Ultrasound evaluations were conducted for those with weak or absent radial pulses to determine any vascular complications. To ensure consistency, the same group of surgeons performed all BA punctures, sheath placements, suturing, and compression procedures.

Intervention management

The patients were positioned supine with the access arm abducted at 90°. Ultrasound imaging was performed to assess the diameter of the BA and identify any calcification. Following successful ultrasound-guided puncture, a sheath of appropriate diameter was inserted into the BA. Radiological examination was used to confirm correct placement and intervention accuracy. The Radifocus Introducer II (5F-7F, Terumo) was inserted over a guidewire as needed for the procedure. To maintain heparinization, each patient received an initial dose of 3000–7000 units of Heparin, with additional doses administered intraoperatively based on the duration of the procedure and the patient’s weight.

Perclose ProGlide group

Patients in this group underwent procedures including thoracic endovascular aortic repair, renal artery angioplasty and stenting, coronary stent implantation, arteriovenous malformation/aneurysm embolization, cerebral angiography, and iliac artery stenting, among others. All patients required high-dose angiography, necessitating postoperative infusion to facilitate the excretion of contrast agents. As postoperative blood pressure monitoring was essential, the Perclose ProGlide system was chosen to free both upper limbs for patient comfort and mobility.

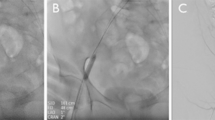

At the conclusion of the procedure, the vascular sheath was removed, and the Perclose ProGlide device was introduced into the vessel over a Radifocus Guide Wire M (150 cm, Terumo) until pulsatile blood flow was observed at the marker lumen. The device was positioned at a 45° angle, and the lever was raised while gently retracting the device until resistance indicated proper footplate placement against the inner wall of the BA. Once positioned, bleeding was controlled as follows:

- The needle plunger stop was pressed for 2 s.

- The plunger was gradually withdrawn while the suture was straightened and cut.

- The lever was reset, the device was removed, and the sutures were held in place.

- The suture knots were tightened, and any excess suture material was trimmed.

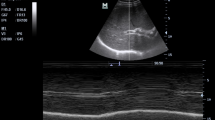

Ultrasound imaging was performed post-procedure to confirm the absence of complications, such as arterial stenosis or pseudoaneurysms (Fig. 1). Once successful suturing was verified, manual pressure was applied to the wound for 3 min. Continuous compression with an elastic bandage was not required. In cases where the initial attempt at hemostasis with the ProGlide device failed, a second attempt with the same device was avoided. This precaution was taken to minimize the risk of BA spasms, vascular injury, or additional procedural failure.

(A), Perclose ProGlide was implanted into the vessel along the guide wire until obvious pulsed blood flow was observed. (B), Held the handle to maintain the suture device 45°up, put up the lever and slightly pulled back the device until resistance is encountered and the bleeding was stopped. Stabilized the instrument and pushed the needle plunger to close the wound. (C), Pressed the wound for 3 min after suturing, no active bleeding or hematoma was observed at the puncture site. (D), Blood flow and vascular morphology was uninterrupted at the puncture site. No existence of artery stenosis, thrombosis and pseudoaneurysm under the check of ultrasonography.

Manual compression group

Patients in this group underwent brief coronary angiography, transluminal coronary angioplasty, and coronary stent implantation without requiring postoperative infusion. Hemostasis was achieved using traditional compression techniques. At the conclusion of the procedure, the vascular sheath was removed, and the puncture site was manually compressed for 15 min. Subsequently, an elastic bandage was applied for 6 h to maintain hemostasis. The bandage was periodically released every 2 h to ensure patient comfort and proper circulation.

Postoperative observation

Each patient underwent an ultrasound examination 6 h postoperatively to assess the condition of the puncture site. Complications such as pain, numbness, hematoma, active bleeding, bruising, arterial occlusion, upper limb swelling and ischemia, pseudoaneurysm, and DVT were meticulously examined and recorded.

The primary complications included pseudoaneurysm, active bleeding, reintervention, ischemia, venous thrombosis, and arterial occlusion. Minor complications, such as hematoma, swelling, bruising, and numbness near the wound, were also documented to evaluate postoperative patient comfort. Hematoma was diagnosed based on the presence of irregularly bordered cystic, mixed, or solid echoes observed on ultrasound, with no detectable blood flow signals within. The presence of sac-like vascular abnormality with blood flow signals was characterized as pseudoaneurysm.

Swelling caused by bandage compression typically subsided promptly once the bandage was removed. Clinically negligible swelling that resolved after decompression, as well as bruising that healed spontaneously, were not included in the statistical analysis of complications. However, persistent swelling, bruising and numbness after decompression were classified as complications and were included in the data.

Follow up

All patients underwent BA examination at the puncture site 7 and 30 days after surgery. Severe complications were examined and treated, including BA stenosis or occlusion, pseudoaneurysm, hematoma, and local neurological dysfunction.

Ethics and consent

This study was approved by the ethics committee of Peking university international hospital (2024-KY-0018–02) and conducted according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The clinical data was obtained in addition to parents’ consent.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed using SPSS version 17.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Data were compared using a two-sample t-test or one-way analysis of variance for parametric data and the Mann–Whitney or Wilcoxon tests for non-parametric data. Data are expressed as mean ± standard error. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Clinical information

The Mann–Whitney U test was employed to evaluate potential heterogeneity between the ProGlide and manual compression groups. The ProGlide group included 25 males and 15 females, with a mean age of 60.20 ± 12.39 years. The manual compression group consisted of 27 males and 33 females, with a mean age of 65.48 ± 10.41 years. No statistically significant differences were observed between the groups in terms of age (P = 0.503), gender (P = 0.086), or general condition. In the ProGlide group, the left side was chosen in 19 patients (47.5%), while the right side was chosen in 21 (52.5%). In the manual compression group, the left side was selected in 6 patients (10.0%), and the right side was selected in 54 (90.0%) (Table 1).

In the ProGlide group, procedural distribution was as follows: 8 patients (20.0%) underwent cerebral angiography or aortography, 7 (17.5%) received renal artery angioplasty and stenting, 6 (15.0%) underwent iliac artery stenting, 9 (22.5%) underwent abdominal arteriovenous malformation/aneurysm embolization, 6 (15.0%) received thoracic endovascular aortic repair, and 4 (10.0%) underwent transcatheter arterial chemoembolization. Conversely, in the manual compression group, 32 patients (53.3%) underwent coronary angiography, 14 (23.3%) underwent transluminal coronary angioplasty, and 14 (23.3%) received coronary stent implantation (Table 2).

Post-procedure, most cases in the ProGlide group required 3 min of compression following closure, with only 1 patient requiring 15 min of manual compression and 6 h of elastic bandage compression due to persistent bleeding. In contrast, all patients in the manual compression group underwent the standard protocol of 15 min of manual compression followed by 6 h of elastic bandage compression.

Access-related complications

No significant differences were observed in the incidence of major complications between the ProGlide and traditional compression groups. Specifically, pseudoaneurysms were detected in two patients (3.3%) in the traditional compression group, while no pseudoaneurysms were observed in the ProGlide group (P = 0.243). Hematomas were reported in six patients (10.0%) in the compression group and five patients (12.5%) in the ProGlide group (P = 0.695). Active bleeding occurred in one case in the ProGlide group and two cases in the traditional compression group (P = 0.811). Neither group reported cases of arterial occlusion, ischemia, or venous thrombosis. Reintervention due to bleeding or hematoma was required for three patients in the traditional group, while no such cases occurred in the ProGlide group (P = 0.151).

In terms of minor complications, a significant difference was observed in postoperative upper limb swelling: 49 patients (81.7%) in the manual compression group experienced swelling, compared to only five patients (12.5%) in the ProGlide group (P < 0.001). Bruising at the puncture site was reported in six patients (15.0%) in the ProGlide group, while 31 patients (51.7%) in the traditional group experienced upper limb bruising (P < 0.001). Regarding long-term complications, numbness around the puncture site was reported by two patients in the traditional group, whereas no cases of neurological dysfunction were reported in the ProGlide group (P = 0.243) (Table 3).

Discussion

Although the femoral or radial artery has traditionally served as the primary access point for most endovascular procedures, the BA is increasingly being utilized as a first-line option due to specific clinical requirements, device configurations, or physician preferences. BA access is generally considered when catheterization via the femoral or radial artery proves to be particularly challenging12. Additionally, the BA offers advantages such as shortening the procedural distance and enhancing the feasibility of using large-bore catheters12. The BA facilitates complex anatomical navigation, supports brachiofemoral access, and provides rigid support for precise stent graft positioning. Moreover, its relatively large artery-to-sheath size ratio permits the placement of large guide catheters and devices. The histological characteristics of the BA, which contains fewer elastic fibers compared to the femoral artery, contribute to its distinct structural profile. While the BA’s thinner wall has traditionally been considered more fragile under manipulation, recent evidence suggests that access-related complications have declined significantly compared to earlier reports13,14,15. Major complications associated with BA puncture include hematoma, pseudoaneurysm, and limb ischemia, which may necessitate additional surgical or endovascular interventions16. To mitigate these risks, alternative VCDs have been introduced in BA interventions. However, the clinical outcomes associated with the use of these devices remain a topic of ongoing debate.

One study evaluated the technical success and adverse event rates of VCDs in the BA compared to manual compression. A meta-analysis of 16 studies (510 access sites) found a high technical success rate for VCDs (93%) and identified adverse event rates, including hematoma (9%), pseudoaneurysm (4%), and neurological events (5%). VCDs showed no significant difference in hematoma formation or overall adverse events compared to manual compression, suggesting they are effective and safe despite being used off-label17.

The Perclose ProGlide system is a widely recognized option for closing large-bore arterial access sites, accommodating sheath sizes ranging from 5 to 21F. Its safety and effectiveness are well-established in transfemoral access applications18,19. In addition, the ProGlide system has been adopted for percutaneous axillary artery access and is regarded as a safe and effective approach for large-bore upper extremity access during complex endovascular aortic repair. Follow-up assessments demonstrated 100% axillary artery patency with a low incidence of complications20.

Despite the BA offering a comparable artery-to-sheath size ratio, limited studies have explored the feasibility and access-related complications of using the Perclose ProGlide device in BA procedures. Previous investigations into this application were discontinued due to an unacceptably high complication rate associated with the ProGlide group8. In light of these findings, this study seeks to further evaluate the reliability of Perclose ProGlide-based closure following BA puncture.

Based on our clinical practice, the Perclose ProGlide device has proven to be both suitable and effective for use in the BA approach, demonstrating notable hemostatic effects. The device enables precise percutaneous suture delivery to seal puncture sites with significantly lower rates of access-related complications. The incidence rates of pseudoaneurysm, hematoma, and reintervention in the Perclose ProGlide cohort were comparable to those observed in the traditional approach. The occurrences of patient discomforts such as swelling, bruising, and pain were also unusual in the ProGlide group.

Furthermore, the elimination of the need for prolonged bandaging significantly enhanced upper limb mobility. The Perclose ProGlide also substantially reduced suture time. In our center, closure times averaged less than one minute, with hemostasis achieved within three minutes of wound compression, allowing surgeons to promptly confirm successful closure. The device promotes single-stage arterial wall healing, minimizing inflammatory responses and facilitating potential reinterventions at the same puncture site. Overall, the application of the Perclose ProGlide in BA access has greatly reduced procedural duration, alleviated the workload of interventional radiologists, and improved patient comfort and satisfaction.

Based on our experience, BA puncture should be performed on the anterior wall only, ensuring that the posterior wall of the vessel remains undamaged. The Perclose ProGlide device is not recommended for trans-wall or multi-site punctures, as such techniques can result in complications like hematoma or pseudoaneurysm formation. Ultrasound guidance is essential during BA puncture to minimize the risk of severe angiolithic degeneration and to prevent damage to the lateral and posterior walls of the artery. Brachial arteriography is a critical step prior to deploying the Perclose ProGlide device to avoid complications such as local vascular spasms or dissection. During the suturing process, a guidewire must be maintained in place until the Perclose ProGlide device is fully removed. This ensures that another device or sheath can be inserted if hemostasis is not achieved. In cases of continuous arterial bleeding, consistent manual compression has been shown to be an effective countermeasure. Patients undergoing diagnostic or therapeutic procedures with BA punctures involving 5–7F sheaths were typically discharged after being observed for two hours post-closure with the Perclose ProGlide device, provided no signs of bleeding were detected.

Limitations

The retrospective study is limited by selection bias and small sample size which requires further randomized controlled prospective study. Some confounders differ between the two groups, making the two cohorts scientifically less comparable.

It’s unclear whether the clinical effects of Perclose ProGlide is consistent for sheaths size above 8F in BA puncture. Besides, no difference of pseudoaneurysm, hematoma and reintervention between two groups were observed in our study which required large sample size of study to clarify. In addition, while the ProGlide device demonstrates significant advantages in terms of operability and convenience, its cost is significantly higher than that of traditional compression methods. Its specific cost–benefit ratio and patient acceptance also require further research for clarification.

This article only discusses the efficacy and safety of closure devices after BA puncture. The type of disease and the specific procedures performed via the BA approach should have minimal impact on the results. However, as a retrospective study, certain inconsistencies in patient selection and surgical methods do exist. Additionally, whether other factors such as hypertension, diabetes, hypercholesterolemia, smoking status, peripheral arterial disease, coronary artery disease, aneurysmal disease, body mass index, and similar indicators affect the safety and efficacy of the ProGlide device also warrants further investigation.

Conclusion

We observed that the Perclose ProGlide device benefits the transbrachial approach in clinical practice. The application of Perclose ProGlide is safe and promising, with higher hemostasis efficiency compared with traditional manual compression.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Vierhout, B. P., Pol, R. A., El Moumni, M. & Zeebregts, C. J. Editor’s Choice - arteriotomy closure devices in EVAR, TEVAR, and TAVR: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised clinical trials and cohort studies. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 54, 104–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejvs.2017.03.015 (2017).

Heenan, S. D., Grubnic, S., Buckenham, T. M. & Belli, A. M. Transbrachial arteriography: indications and complications. Clin. Radiol. 51, 205–209. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0009-9260(96)80324-2 (1996).

Malgor, R. D., de Marino, P. M., Verhoeven, E. & Katsargyris, A. A systematic review of outcomes of upper extremity access for fenestrated and branched endovascular aortic repair. J Vasc Surg 71, 1763–1770. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvs.2019.09.028 (2020).

Maciejewski, D. R. et al. Clinical situations requiring radial or brachial access during carotid artery stenting. Postepy. Kardiol. Int. 16, 410–417. https://doi.org/10.5114/aic.2020.101765 (2020).

Franz, R. W., Tanga, C. F. & Herrmann, J. W. Treatment of peripheral arterial disease via percutaneous brachial artery access. J. Vasc. Surg. 66, 461–465. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvs.2017.01.050 (2017).

Alvarez-Tostado, J. A. et al. The brachial artery: a critical access for endovascular procedures. J. Vasc. Surg. 49, 378–385. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvs.2008.09.017 (2009).

Pieper, C. C., Wilhelm, K. E., Schild, H. H. & Meyer, C. Feasibility of vascular access closure in arteries other than the common femoral artery using the ExoSeal vascular closure device. Cardiovasc. Int. Radiol. 37, 1352–1357. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00270-014-0853-x (2014).

Meertens, M. M., de Haan, M. W., Schurink, G. W. H. & Mees, B. M. E. A Stopped pilot study of the proglide closure device after transbrachial endovascular interventions. J. Endovasc. Ther. 26, 727–731. https://doi.org/10.1177/1526602819862775 (2019).

Wei, X. et al. A Retrospective study comparing the effectiveness and safety of exoseal vascular closure device to manual compression in patients undergoing percutaneous transbrachial procedures. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 62, 310–317. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avsg.2019.06.031 (2020).

Mirza, A. K. et al. Analysis of vascular closure devices after transbrachial artery access. Vasc. Endovascular Surg. 48, 466–469. https://doi.org/10.1177/1538574414551576 (2014).

Abdel-Wahab, M. et al. Comparison of a pure plug-based versus a primary suture-based vascular closure device strategy for transfemoral transcatheter aortic valve replacement: The CHOICE-CLOSURE randomized clinical trial. Circulation 145, 170–183. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.121.057856 (2022).

Mirza, A. K. et al. Outcomes of upper extremity access during fenestrated-branched endovascular aortic repair. J. Vasc. Surg. 69, 635–643. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvs.2018.05.214 (2019).

Petrov, I., Stankov, Z., Tasheva, I. & Stanilov, P. Safety and efficacy of transbrachial access for endovascular procedures: A single-center retrospective analysis. Cardiovasc. Revasculariz. Med: Inc. Mol. Int. 21, 1269–1273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carrev.2020.02.023 (2020).

Stavroulakis, K. et al. Efficacy and safety of transbrachial access for iliac endovascular interventions. J Endovasc Ther : An official J. Int. Soc. Endovasc. Specialists 23, 454–460. https://doi.org/10.1177/1526602816640522 (2016).

Lee, D. G., Lee, D. H., Shim, J. H. & Suh, D. C. Feasibility of the transradial or the transbrachial approach in various neurointerventional procedures. Neurointervention 10, 74–81. https://doi.org/10.5469/neuroint.2015.10.2.74 (2015).

Mantripragada, K., Abadi, K., Echeverry, N., Shah, S. & Snelling, B. Transbrachial access site complications in endovascular interventions: A systematic review of the literature. Cureus 14, e25894. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.25894 (2022).

Koziarz, A. et al. The use of vascular closure devices for brachial artery access: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 34, 677–684. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvir.2022.12.022 (2023).

Reifart, J. et al. Single versus double use of a suture-based closure device for transfemoral aortic valve implantation. Int. J. Cardiol. 331, 183–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2021.01.043 (2021).

Dunn, K. et al. Safety and effectiveness of single ProGlide vascular access in patients undergoing endovascular aneurysm repair. J. Vasc. Surg. 72, 1946–1951. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvs.2020.03.028 (2020).

Al, A. Z. et al. Safety and learning curve of percutaneous axillary artery access for complex endovascular aortic procedures. J. Vasc. Surg. 79, 487–496. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvs.2023.10.048 (2024).

Acknowledgements

All contributors to this study are included in the list of authors.

Funding

This article was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant number: 82403302).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Peng Zhao and Yao Yao worte the main MS and prepared figure and tables. Quan Yang, Ning Wang and Liang Wang provided the clinical data. Qianquan Ma and Wenchao Zhang supervised the whole procedures. All authors reviewed the MS.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhao, P., Yao, Y., Yang, Q. et al. Application of Perclose ProGlide closure device in transbrachial endovascular intervention. Sci Rep 15, 2807 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86896-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86896-x