Abstract

This study presents a blueprint for developing, scaling, and analyzing novel insect cell lines for food. The large-scale production of cultivated meat requires the development and analysis of cell lines that are simple to grow and easy to scale. Insect cells may be a favorable cell source due to their robust growth properties, adaptability to different culture conditions, and resiliency in culture. Cells were isolated from Tobacco hornworm (Manduca sexta) embryos and subsequently adapted to single-cell suspension culture in animal-free growth media. Cells were able to reach relatively high cell densities of over 20 million cells per mL in shake flasks. Cell growth data is presented in various culture vessels and spent media analysis was performed to better understand cell metabolic processes. Finally, a preliminary nutritional profile consisting of proximate, amino acid, mineral, and fatty acid analysis is reported.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cultivated meat (CM) is an emerging technology dedicated to producing meat from cell culture instead of whole animals. Entomoculture, or culturing insect cells for food, may be a promising alternative to “traditional” livestock cell sources for CM. This is because insect cells are relatively adaptable and resilient in culture, leading to improved scalability at a lower cost. However, studies on insect cell culture bioproduction systems have primarily analyzed cells in the context of generating biologicals (e.g., recombinant proteins, viruses). The present study builds upon previous entomoculture proof-of-concept studies in an effort to demonstrate the feasibility of insect cells as an ingredient in CM products.

Cultivated meat

Growing evidence has shown that traditional animal agriculture is replete with environmental, animal welfare, and human health concerns1. To mitigate these issues, researchers are investigating how to produce traditionally animal-derived products from cell culture. To date, the focus for the field has been on cells cultured from livestock or seafood species to create cultivated meat (CM) or seafood products. Since the field’s inception approximately 10 years ago, many scientific and regulatory achievements have been accomplished. Notably, in 2023, two companies received permission from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) to commercialize cultivated chicken products made with embryonic chicken fibroblasts, signifying a major milestone for CM production in the United States2. In addition to chicken, companies and academic researchers have been investigating bovine, porcine, and piscine cell lines for CM products3,4,5,6.

While significant progress has been made in developing these cell lines within the constraints of CM (animal-component free cell culture media, easy transition to large-scale culture, favorable nutritional and sensory properties), widescale production remains limited by technical challenges. For example, animal-component free media is available for some cell types but can slow growth relative to fetal bovine serum (FBS)-containing media7, microcarriers are often required for suspension culture (adding complexity and cost)8,9, and achieving high cell densities in single-cell suspension is often contingent upon excessive growth media usage5.

Insect cells are promising alternatives. Compared to livestock, insects have had incredible evolutionary success, making up the largest and most diverse group of organisms in the animal kingdom10. They are capable of surviving in extreme environments and are tolerant of thermal, osmotic and toxic stresses11. Many features that make insects resilient and adaptable translate to the cellular level. Insect cells are known for their robust growth, ability to easily scale, and adaptability to different environmental and growth media conditions12,13. The goal of this project was to establish an isolation procedure to develop a new insect cell line that is scalable, easily adaptable to animal component-free media and generates sufficient biomass to assess nutritional properties. This approach is intended to provide a framework for future research into other insect species and to further explore the potential of large-scale insect cell culture for consumption. Although the final use-case for entomoculture cell lines compared with traditional biotechnology insect cell culture are different (food ingredients vs. biological production), many of the reasons insect cells are favorable for CM were previously established in adjacent industries.

Insect cells in biotechnology

Historically, motivation for insect cell cultivation has been to produce biologicals, mainly recombinant proteins and biopesticides. As interest grew in using insect cell culture over the past century, focus turned to developing fast-growing cells in large-scale culture. Insect cells are favorable for scale-up because they: (1) typically grow well in single-cell suspension and reach higher cell densities than mammalian cells, (2) are easily adaptable to serum- and animal component-free media, thus reducing scale-up costs and batch-to-batch variability of animal components, and (3) grow at near-room temperature and without CO2 supplementation, simplifying culture conditions13.

The most commonly used insect cell lines in biotechnology are Sf9 cells, isolated from ovarian tissue of the fall armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda) and High-Five cells, isolated from ovarian tissue of the cabbage looper (Trichoplusia ni)13. Commercial use of insect cells for human therapeutics includes FluBlock (a flu vaccine produced in Sf9 cells)14, Cervarix (a cervical cancer vaccine produced in High-Five cells)15, and NovaVax (a COVID-19 vaccine that uses Sf9 cells to produce a recombinant SARS-CoV-2 spike protein)16,17. These industries provide a precedent for the scalability of insect cell culture and a solid foundation for further research into using insect cells for food.

Entomoculture

In 2007, researchers at Wageningen University proposed using insect cells cultivated in bioreactors to generate edible protein. The rationale behind this idea was that whole insects are nutritionally favorable with respect to their mineral and digestible protein content, and in vitro growth offers a high level of control and customization18. As CM gained traction in the past decade, the idea of growing insect cells for consumption (entomoculture) resurfaced, again motivated by the fact that infrastructure already exists for large-scale insect cell culture, and compared with “traditional” livestock species, insect cells are extremely adaptable and resilient in culture12.

Entomoculture does not necessarily aim to recreate edible insect products in vitro – rather, it aims to use insect cells as the animal cell ingredient in a variety of cultivated meat products, providing the sensory and nutritional advantages of animal meat with a potentially easier and more cost-effective path to scale-up than conventional livestock species. The advantageous qualities of insect cells that render them suitable for production of biologicals also position them as an efficient system for generating biomass directly from the cells themselves. Incubation systems can be simplified and facility costs lowered by room-temperature growth without CO2, animal components can be removed from biomass production with easy adaptation to animal-free media formulations, and the lack of contact inhibition can help to reach higher cell densities19,20. Insect cells also grow well in the absence of growth factors such as insulin, transferrin, fibroblast growth factor, and transforming growth factor beta, which are typically used for mammalian cell culture and contribute to the high cost for large-scale CM12,21. Despite the potential for insect cells for CM, previous research into developing and studying insect cells in a food context have been extremely limited.

Previous work

Research in our laboratory has shown proof-of-concept data supporting the use of insect cells for CM, however cells have not been analyzed beyond small bench-scale. For example, a Drosophila melanogaster (fruit fly) muscle cell line was adapted to serum-free media and formed differentiated muscle fibers in chitosan films and sponges19. In this study, cells were adapted to single-cell suspension using dextran sulfate to reduce cell aggregation in bench-scale shake flasks at low cell densities19. Embryonic cells from Manduca sexta (tobacco hornworm caterpillar) have also been explored for cultivated fat, accumulating lipids upon treatment with a soybean oil emulsion, with a fatty acid breakdown similar to whole caterpillars20. A preliminary technoeconomic assessment has also been performed, which projects that insect cell lines cultured in the context of CM have significantly lower media, oxygen consumption, and utility costs compared with mammalian cells, resulting in lower production costs per kilogram22.

Although insect cells have been used in biotechnology for biological production for decades, there are gaps in strategies to generate new cell lines optimized for food-related goals. Here, we demonstrate the generation of an insect cell line from M. sexta embryos, with cell line development and analysis specifically tailored toward the goals of CM. M. sexta was selected as it is a relatively well-characterized lepidopteran model organism. M. sexta’s developmental cycle includes an embryonic, larval (caterpillar), pupal, and adult (moth) stage23,24. Cells were isolated from embryos because previous research has shown robust embryonic cell growth, presenting an opportunity to select for desirable traits (e.g., growth in suspension and animal-free culture media)20,25. Once a cell line was established that showed robust growth in animal-free culture media, traits relevant for CM production and consumption were explored, including high-density growth in single-cell suspension, spent media analysis, and nutritional profiling.

Materials and methods

Cell isolation

M. sexta non-adherent cells (MsNACs) were isolated as described previously25 with some alterations. Briefly, M. sexta eggs were staged at 19–22 h (stage three of development23), sterilized with 50% sodium hypochlorite solution for 5 minutes, rinsed with growth media and lysed using a Dounce homogenizer. All institutional guidelines for invertebrate handling were followed. Homogenate was filtered through a 70-micron filter, centrifuged at 40 xg for 10 min to remove debris, and the supernatant was transferred to a fresh tube and centrifuged for 10 min at 380 xg. The top layer of the supernatant (1 mL) was transferred to a 12.5 cm2 T-flask that was filled completely with growth media and incubated at 27 °C for 12 days. After 12 days, media was refreshed, and a 50% media exchange was performed twice over two weeks. Non-adherent cells were routinely subcultured at 90% confluency by lightly pipetting media at the bottom of the flask to detach cells and seeded at 100,000 cells/cm2. Initial growth media was Shields and Sang M3 media (S8398, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis MO) supplemented with 0.5 g/L potassium bicarbonate, 2.5 g/L bactopeptone, 1 g/L yeast extract and 10 (vol./vol.)% heat inactivated fetal bovine serum. Cells were transitioned to SF900 III (12658019, ThermoFisher, Waltham, MA) after passage 4 (see Serum-Free Media Adaptation, Sect. 2.2). 1X Antibiotic-Antimycotic (ThermoFisher 15240096) was used during preliminary culture but was removed after the third passage.

Serum-free media adaptation/nonadherent cell selection

After 4 passages in growth media containing 10% fetal bovine serum, cells were gradually adapted to SF900 III animal component-free media (ThermoFisher 12658019). Cells were passaged into 75% serum-containing and 25% serum-free media at 100,000 cells/cm2. Every 5 days, non-adherent cells were collected and seeded in a new flask with 25% reduced serum until cells were cultured in 100% SF900 III animal component-free media. For 6 months, cells were passaged each week by collecting nonadherent/lightly adherent cells by gently pipetting media over the bottom of the culture flask, removing the media containing floating cells, and diluting the media and cell suspension 1:3 into a fresh T-flask. After 6 months, cells were transferred to 125 mL shake flasks and maintained in suspension for the duration of the study unless otherwise noted.

Cryopreservation

MsNACs were expanded in cell culture flasks and harvested after reaching 90% confluency. Cells were centrifuged at 380 xg for 5 min and resuspended at 10E6 cells/mL in freezing media (45% conditioned media, 45% fresh media and 10% dimethyl sulfoxide). Cells were transferred to cryovials and frozen in a cryobowl at 80 °C overnight before relocation to long-term liquid nitrogen storage. Cell viability and doubling time was determined from four different passages with an automated cell counter (NC-200™, Chemometec) after thawing cryopreserved cells. Each vial of cryopreserved cells was allowed to recover for 4–5 days after thawing in a T25 flask. After one week, 100,000 viable cells/cm2 were passaged into a fresh flask and cell viability and doubling time was determined with an automated cell counter (NC-200™, Chemometec) after 5 days of growth. This process was repeated for four separate cryopreserved vials (P34, P36, P41, P42) and measurements were compared to doubling time/viability recorded prior to cryopreservation.

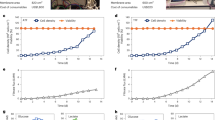

Growth curves

MsNACs were seeded at 500,000 cells/mL in a 30 mL working volume in 125-mL shake flasks (ThermoFisher 4113 − 0125) in triplicate. For highest achievable cell density studies, 120 µL cell suspension was removed at 24-hour intervals and cell count and viability were determined with an automated cell counter (NC-200™, Chemometec). Once cells reached over 3E6 cells/mL, a 50% media exchange was performed every other day by removing half of the media and cell suspension, centrifuging at 300 xg for 5 min, aspirating spent media, and resuspending cell pellet with fresh media before adding it back to the flask. For batch growth curves, cells were counted each day without media exchange until growth rates plateaued (Fig. 1).

Establishment of spontaneously immortalized embryonic Manduca sexta cell population that proliferates in single-cell suspension in animal-component free media. (A) Schematic of cell line development process. (B) Phase contrast images of cells isolated from buoyant layer at passage 0 (top), passage 4 (middle), and passage 37 (bottom). Scale bar = 100 microns. (C) Tracking of cell doublings up to 100 cumulative cell doublings, representing spontaneous cell immortalization. (D) Analysis of cells before and after cryopreservation; doubling time (left), cell diameter in microns (middle), and viability (right) n = 3–4, t-test, ns = not significant.

Bioreactor runs

Bioreactor experiments were carried out in a 2.4-liter airlift bioreactor. All glass bioreactor components were pre-coated with Sigmacote, (SL2, Sigma-Aldrich) dried overnight, and thoroughly rinsed before use. Passage 30–40 MsNACs were expanded in shake flasks before inoculation into the 2.4-L bioreactor at a viable cell density of 500,000 cells/mL. Culture media was supplemented with 0.5% Antibiotic-Antimycotic (15240096, ThermoFisher Scientific). The bioreactor was operated in batch mode, with media only added as needed to counteract volume lost through evaporation and sampling. The bioreactor was operated at 27oC with an air sparge rate of 0.5 LPM. 1–2 mL of a 1:100 mixture of an antifoam agent and Reverse Osmosis Deionized water was added as needed to minimize foaming levels. For harvesting cells used in Sect. 2.8, the cell culture was removed in aliquots of 500 mL and spun down at 325xg for 13 min. The spent media was aspirated, and the resulting cell pellets were resuspended in 5mL of Phosphate-Buffered Saline to wash, combined into one 50 mL tube, and re-spun down at the same conditions. The Phosphate-Buffered Saline was aspirated, and the resulting pellet was weighed before being stored at -20oC until further analysis. Figure 2 represents cell counts taken with an automated cell counter (NC-200™, Chemometec) at matched timepoints to a parallel 500 mL shake flasks over three passages. Additional measurements (beyond the matched timepoints) were recorded for the 2.4 L bioreactor over the three passages and are shown in SI Fig. 2.

Suspension growth of MsNACs. (A) Highest achievable density of MsNACs with media exchange on left axis, with viability shown on the right axis (n = 3). (B) Highest achievable cell density of MsNACs without media exchange on left axis, with viability shown on the right axis (n = 3). (C) Growth over three passages in 500 mL shake flasks. (D) Growth over three passages in a 2.4-liter bioreactor.

Spent media analysis

During batch shake flask culture, each day 500 µL was removed from shake flasks. Cell suspension was spun down at 300xg and 450 µL cleared supernatant was preserved at -80oC for further analysis using either ViCELL Metaflex bioanalyzer (Beckman Coulter) or Cedex Bio Analyzer (Roche). Throughout the bioreactor runs, samples were taken 2x daily. Glucose and lactate were analyzed using the Vi-CELL Metaflex bioanalyzer (Beckman Coulter) and all other metabolites were measured on a Cedex Bio Analyzer (Roche). All bioreactor metabolite measurements were performed at time of sampling.

Ammonia and lactate supplementation

Passage 50 MsNACs were expanded in shake flasks before being seeded into 48-well plates to assess growth and viability. Serial dilutions of either ammonium chloride (ThermoFisher, A15000.0I) or sodium lactate (ThermoFisher, L14500.06) were prepared from 100 to 3.13 mM in Sf900 III medium. Cells were seeded at 50,000 cells/cm2 in 48-well plates with 5 replicates of each condition. Over 5 days, confluency was monitored with a Celigo Image Cytometer (Nexalom Bioscience). After 7 days, cells were imaged using a phase contrast microscope (BZX-810, Keyence) and viability was analyzed using a LIVE/DEAD stain (ThermoFisher, R37601), and again imaged using a fluorescence microscope (BZX-810, Keyence). Figure 3C and E represent proportions of total cells analyzed that were live and dead. Significance represents an ANOVA performed on the proportion of live cells in each condition.

Spent media analysis and inhibitory concentrations of lactate and ammonia. (A) Spent media analysis for ammonia, glutamate, l-glutamine, glucose and lactate for cells grown in Fig. 2B, with red line indicating timepoint of growth cessation (n = 3 flasks) (B) Growth over 5 days as measured by confluency in 48-well plates for MsNACs growth with increasing concentrations of sodium lactate. Mixed effects ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test (n = 5). (C) Proportion of live and dead cells as measured by calcien AM (live) and propidium iodide (dead) after 7 days of growth with increasing concentrations of sodium lactate. 1-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test (n = 3) (D) Growth over 5 days as measured by confluency in 48-well plates for MsNACs growth with increasing concentrations of ammonium chloride. Mixed effects ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test (n = 5). (E) Proportion of live and dead cells as measured by calcien AM (live) and propidium iodide after 7 days of growth with increasing concentrations of ammonium chloride. 1-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test (n = 3). *<0.05, **<0.01, ***<0.001, ****<0.0001.

Proximate nutritional analysis

Three separate 10–15 gram (wet weight) MsNAC samples were collected as described in Sect. 2.5 (“Bioreactor Runs”) above and stored at -20oC until further analysis. Proximate analysis of MsNAC cell samples was conducted at Eurofins Scientific, Inc. (Eurofins Nutrition Analysis Center, Des Moines, IA). An abbreviated Nutrition Labeling and Education Act (NLEA) analysis was performed with methods established by the Association of Official Analytical Chemists (AOAC). Moisture content was analyzed by forced draft oven (AOAC 925.09), protein by combustion in a protein analyzer (AOAC 990.03, AOAC 992.15), ash by heating at 600oC (AOAC 942.05), and crude fat by acid hydrolysis (AOAC 954.02). Carbohydrate content was calculated by subtracting the sum of ash content, crude fat content, and protein content from 100%. Data is represented as dry weight calculated by proportions of each component as a percent of all measurements except moisture.

Amino acid, fatty acid, mineral analysis

Samples were collected from either MsNACs or DF-1 cells grown in single-cell suspension. MsNACs were seeded at 500,000 cells/mL in 30 mL working volume in 125-mL shake flasks (ThermoFisher 4113 − 0125) in a shaking incubator set at 27oC with 110 RPM agitation. DF-1 cells were obtained from ATCC cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium + 10% Fetal Bovine Serum + 1% antibiotic/antimycotic. Cells were inoculated at 50,000 cells/cm2 in a 39oC shaking incubator with 5% CO2 set at 80 RPM. For both cell types, 50 million cells were removed from separate flasks, centrifuged at 300 xg for 5 min, rinsed with sterile PBS, and cell pellets stored at -20oC until further analysis. Separate samples (n = 4 for MsNACs, n = 3 for DF-1) were collected for amino/fatty acid and for metal analysis. Food composition assays were performed at The Metabolomics Innovation Centre (TMIC) at the University of Alberta. Briefly, cells were lysed with 50% methanol and 50% water and four rounds of freeze-thaw in liquid nitrogen. Each sample was centrifuged at 16,000 xg for 10 min, and the supernatant used for Liquid Chromatography with Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) analysis. A targeted quantitative metabolomics approach was used as previously described26. A direct injection mass spectrometry with a reverse-phase LC-MS/MS custom assay was combined with an ABSciex 4000 QTrap (Applied Biosystems/MDS Sciex) mass spectrometer. Data was analyzed using Analyst 1.6.2. Metabolites were quantified using isotope-labeled internal standards. For metal analysis, Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS) was performed on a NexION 350x ICP–MS (Perkin-Elmer, Woodbridge, ON, Canada) using previously described methods27,28. One 20-gram sample was sent to Eurofins for Amino Acid analysis via acid hydrolysis (Eurofins code QQ176). Results from Eurofins were reported as percentages, and SI Fig. 4C represents percentage of each amino acid of total analyzed amino acids.

Nutritional analysis of MsNACs. (A) Dry weight breakdown as analyzed via combustion of 3 separate 15–20 gram samples of MsNACs. (B) phase contrast images of MsNACs (top) and DF-1 cells (bottom) SB = 100 microns. (C) Cell size comparison between MsNACs and DF-1 cells as analyzed by ImageJ (n = 3 fields of view, 30–80 cells per field of view). (D) Protein concentration as measured in picograms per cell via BCA assay (n = 3). (E) Proportion of each essential amino acid as a percent of all amino acids analyzed via UPLC-MRM/MR of MsNAC and DF-1 cells. n = 3–4, 2-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparisons test ***<0.001, *****<0.0001. (F–L) comparison of MsNAC (yellow) and DF-1 (blue) metals via ICP-MS reported in micromolar. t-test, *<0.05 ns = not significant.

DF-1 comparisons

Protein concentrations of MsNAC and DF-1 cells were compared via a Bicinchoninic Acid Kit (BCA) (A55864, Thermo Scientific). MsNAC and DF-1 cell samples were centrifuged at 600xg for 5 min to isolate the cell pellet, rinsed with Phosphate Buffered Saline, and resuspended and lysed in Radioimmunoprecipitation Assay Buffer (RIPA buffer). Samples were then centrifuged at 14000xg for 10 min and supernatant was transferred into new tubes for each condition. BCA standards, using RIPA as diluent, and BCA working reagent were prepared as outlined in the Thermo Scientific Pierce™ BCA Protein Assay Kit protocol. Standards, samples, and working reagents were transferred into a 96-well plate at a sample to working reagent ratio of 1:8. The well plate was incubated at 37oC for 30 min and absorbance was measured at 562 nm on a Synergy H1 microplate reader (BioTek Instruments, Winooski, VT, USA). DF-1 and MsNACs were imaged via light microscope at 40x and subsequently analyzed for area and diameter using ImageJ.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with GraphPad Prism Version 9 software (San Diego, CA, USA). All experiments were performed in triplicate unless otherwise noted in figure legends. Unpaired t-tests were performed for comparing means between two samples (i.e., the mean doubling time, cell diameter, and viability collected from 3 to 4 replicates of cells from different passages before vs. after cryopreservation in Fig. 1, and the mean concentrations of metals (in micromolar) from 3 to 4 separate flasks of MsNACs compared with DF-1 cells in Fig. 4). For comparisons of more than two samples, a one-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was performed to compare multiple groups with a single factor (e.g., cell viability with various ammonia or lactate concentrations in Fig. 3). A two-way ANOVA was performed for experiments involving two independent variables (e.g., proportions of essential amino acids compared between MsNACs and DF-1 cells in Fig. 4). A mixed effects ANOVA was performed for experiments with both independent variables and repeated measures (e.g., percent confluency over multiple days with various lactate or ammonia concentrations). Multiple comparisons were analyzed via Dunnet’s post-hoc test unless otherwise noted in figure legend. P-values < 0.05 were considered significant. Errors represent mean ± standard deviation.

Results

Primary culture: MsNAC culture yielded cells that proliferate in animal-origin free media

Cells were isolated from M. sexta embryos as shown in Fig. 1. Although a range of cell morphologies were observed from the cell pellet after centrifugation (SI Fig. 1A), the initial population from the floating layer appeared to primarily consist of lipid-filled cells (Fig. 1B). After media refreshment, a relatively homogenous and rapidly proliferating cell population emerged and was passaged (Fig. 1B). Cells could also be expanded from the pellet, but cells from the floating layer proliferated faster and a larger proportion were nonadherent, and thus were selected for further expansion. Because the goal of this study was to generate cells that could proliferate in single-cell suspension, only non-adherent or lightly adherent cells were expanded. Fetal bovine serum and antimicrobials were removed after four passages. Interestingly, once serum was removed cells adhered more tightly to the tissue culture plastic and an elongated morphology was observed (SI Fig. 1B). However, further selection for non-adherent cells over multiple passages in Sf900 III media resulted once again in a more rounded phenotype (Fig. 1B).

Selection for non-adherent cells in static culture in Sf900 III media was continued for approximately 6 months. At passage 25, cell morphology, viability, and growth rate appeared consistent, and cells were named “Manduca sexta Non-Adherent Cells,” or “MsNACs.” Cell expansion continued, and consistent growth rates were observed as cells reached over 100 doublings, indicating that MsNACs had spontaneously immortalized (Fig. 1C). After approximately 40 doublings, cells were transferred to suspension culture. Cells continued to grow at consistent rates past 100 doublings and have been maintained as a continuous culture in suspension for over 1.5 years with an average doubling time of 33.5 +/- 6.3 h between passage 80–95 (SI Table 1).

Growth rate and viability before and after cryopreservation was analyzed, as cell banking is essential for large-scale cell expansion. As the high protein content in fetal bovine serum aids in protecting cells during cryopreservation, serum-free cryopreservation can be challenging. Although cells exhibited poor (< 50%) viability upon initial thawing (data not shown), after one passage and approximately one week of recovery the doubling times and viability did not significantly differ from pre-cryopreservation numbers (Fig. 1D). Of note, doubling times represent total cell growth over five days in static culture; log phase doubling time decreased to ~ 30 h in both conditions. Morphology also appears unchanged after thawing (SI Fig. 1D), and cell size did not change (Fig. 1). In addition, cells were confirmed to be mycoplasma free across multiple passages (SI Fig. 1E). Finally, species validation was performed to confirm the expanded cells were indeed derived from the original isolation. Cells from three separate passages were confirmed to be 99.25 +/- 0.29% similar to published M. sexta COI sequences, with less similarity to the related species Manduca quinquemaculata (the tomato hornworm), and significantly different from other commonly studied lepidoptera species, Bombyx mori and Spodoptera frugiperda (97.39 +/- 0.29%, 89 +/- 0.28%, and 89 +/- 1.85%, respectively, SI Fig. 1C).

MsNACs proliferate in shake flask culture and reached densities over 20E6 cells/mL

MsNACs reached over 25E6 cells/mL in shake flasks with media exchange before growth rates slowed dramatically (Fig. 2A). Although cell viability dropped below 90% at 8-10E6 cells/mL, it never decreased below 80% for the duration of the study (Fig. 3A). Similar trends were observed in cells at higher passages (P50) after cryopreservation, although cell viability at densities over approximately 10E6 cells/mL were decreased (SI Fig. 2A). In batch culture without media exchange, cells reached an average of 4.34 +/- 0.77E6 cells/mL over 7 days, with viability remaining above 92% (Fig. 2B). Optimization of biomass production was also explored by comparing media exchange (removal and replacement of 50% of the media every other day) with fed-batch (adding 5 mL of fresh media every other day to a 125-mL shake flask culture without removing spent media). Although viable cell densities remained similar, after 8 days the fed-batch had significantly more total cells as there was a greater total volume with the same cells/mL (SI Fig. 2D). This is a favorable approach, as fed-batch offers a simpler feeding paradigm and uses less media overall. Two other commercial insect animal-origin free media were explored: ExpiSF™ CDM (Thermofisher A3767801) and ESF AF™ (VWR 101419-848). Cells were gradually adapted to the new media formulations over 4 passages with 25% increases in the new media each passage. At 75% new medium and 25% Sf900 III media, cells were observed to have unhealthy morphology in ESF AF™ media and ceased growth (data not shown). In ExpiSF™ CDM, cells had slightly longer lag phases compared with Sf900 III and reached similar cell densities during starvation, thus Sf900 III media was selected for scale-up and spent media studies (Supplemental Fig. 2E).

MsNACs were scaled to a 2.4-liter bioreactor

Once consistent cell growth was observed in small-scale shake flasks, cells were grown in benchtop pneumatic bioreactors to determine feasibility of a MsNAC at-scale production process. Over the three passages, cell viability in the 2.4 L bioreactor was generally lower compared to 500-mL shake flasks but did not drop below 80% (results not shown), while cell densities were similar between the two vessels over three passages (Fig. 2C, D). Doubling times in the 2.4 L were 44.32 +/- 8.77 h from inoculation to passage and dropped to 23.6 +/- 7.9 during the fastest period of growth (on either day 2 or 3 of growth, SI Table 1). MsNACs were also successfully grown in a 10-L bioreactor, reaching a peak density of approximately 2E6 cells/mL with slower than expected growth (SI Fig. 2B). With further optimization of culture conditions at this larger scale, more efficient cell growth would be anticipated.

Spent media analysis offers insight into MsNAC metabolism

Although cells survive and grow at densities above 20E6 cells/mL, without media exchange cell density typically cannot reach above ~4E6 cells/mL in SF900 III media (Fig. 2). Spent media from cells grown in Fig. 2B was analyzed to understand why growth ceased. Throughout the course of 7 days of batch culture (with growth slowing around day 5), glutamate was largely exhausted, but interestingly glucose was not consumed, and glutamine fluctuated but remained above 10 mmol at day 7 (Fig. 3A). Metabolic byproducts were also analyzed: lactate was produced at extremely low rates (less than 1 mmol), and ammonia was consistently produced and reached over 15 mmol over 7 days (Fig. 3A). Similar trends were observed in the 2.4 L bioreactor, indicating that cell metabolism was consistent regardless of culture vessel (SI Fig. 3B). Dissolved oxygen remained relatively stable, but carbon dioxide and the pH of the spent media increased over the 7-day period (Supplemental Fig. 3A). Because metabolite buildup likely inhibits cell growth, the effects of lactate and ammonia were tested by adding increasing concentrations of either sodium lactate or ammonium chloride to cells in fresh media and observing cell growth. MsNACs appear to be unaffected by sodium lactate up to 12.5 mM (although the proportion of live cells decreased slightly), but growth was drastically decreased above 25 mM (Fig. 3B, C, SI Fig. 3E). Since lactate production is normally below 1 mM, it is unlikely that it contributes to the slowed growth. In contrast, ammonium chloride added to cells had a detrimental effect within the range of ammonia produced by cells in Fig. 3A. After five days exposure to concentrations above 6.25 mM growth was slowed, although the most dramatic effects were seen above 25 mM (Fig. 3D, E). Notably these effects were not due to changes in pH, which remained between 6.09 and 6.22 in all conditions (SI Fig. 3C).

Analysis of MsNAC nutritional profile

Proximate analysis, amino acid, fatty acid, minerals

Preliminary nutritional analyses were performed on MsNACs grown in single-cell suspension in animal-component free medium in 2.4 and 10-liter bioreactors. Dry weight calculations showed MsNACs consisted of 77.47 +/-2.2% protein, 13.53 +/- 2.27% fat, 8.1 +/- 1.51% ash, and 0.92 +/- 0.1% carbohydrate (Fig. 4A). MsNACs had all nine essential amino acids based on UPLC-MRM/MR analysis, with individual breakdowns (µM) shown in SI Table 2. Metal analysis was also performed via ICP-MS, and results are reported (µM) in SI Table 2. Heavy metals (lead, arsenic, and cadmium) were not detected.

Comparisons to embryonic chicken fibroblasts

To place these nutritional data in context, MsNACs were compared to embryonic chicken fibroblasts (DF-1 cells). Spontaneously immortalized embryonic chicken fibroblasts are currently the only CM generated cells approved for consumption in the United States through the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), who jointly regulate CM29. Data for the dry weight composition and amino acid proportions were obtained from safety documentation published by the California-based cultivated meat companies Good Meat and UPSIDE, who both use embryonic chicken fibroblasts for their cultivated chicken products. Data was also obtained from DF-1 cells cultured in single-cell suspension in-house for the metal analysis and the amino acid analysis (Fig. 4E-L). Breakdown of dry weight protein, fat, ash, and carbohydrates were similar between MsNAC and the embryonic chicken fibroblasts from GOOD meat and UPSIDE; MsNACs had significantly higher carbohydrates compared with GOOD meat, but significant differences were also seen between UPSIDE and GOOD protein and ash composition (SI Fig. 4A). MsNACs had significantly decreased proportions of lysine, threonine, and valine compared with DF-1 cells (SI Fig. 4B). When comparing normalized proportions of essential amino acids, MsNACs had significantly more methionine and significantly less lysine compared with DF-1 cells (Fig. 4E). All other amino acids had no significant differences (Fig. 4E). One 20-gram wet cell weight sample was also analyzed by acid hydrolysis, with percentages of amino acids shown in SI Fig. 4C. The relative amount of each amino acid was similar to embryonic chicken fibroblasts and conventional chicken as reported in safety dossiers from two separate CM companies (SI Fig. 4C). There were no significant differences in zinc, magnesium, copper, sodium, and phosphorous concentrations between cell types, however MsNACs had significantly more iron and calcium compared with DF-1s (SI Table 4 F-L). Finally, fatty acids were analyzed via LC-MS/MS and compared between MsNACs and DF-1 cells (SI Fig. 4D, SI Tables 5, 6, 7 and 8). Results are broken down into free fatty acids, lysophosphatidylcholines (LysoPC a), and phosphatidylcholine diacyl (PC aa). There are minimal differences between DF-1 and MsNACs on the fatty acid level, although MsNACs have significantly higher C2 (Acetic Acid), PC aa C32:2 and PC aa 34:2. Besides PC aa 32:2 and PC aa 34:2, DF-1s have significantly more of many PC aas.

Discussion

Widespread adoption of CM is contingent upon the generation of scalable, cost-effective, meat-relevant cell lines. Here, we present a relatively simple protocol to develop lepidopteran cell lines from embryos that can be grown in animal-free culture media and easily adapted to high-density single-cell suspension culture. Although insect cells have been grown for decades to produce biologicals, cell line development and analysis has previously been constricted to basic growth kinetics and recombinant protein/viral output30,31,32. In contrast, the Manduca sexta non-adherent cells (MsNACs) generated here were analyzed with the goal of biomass production for consumption. Some aims are shared between these two applications: growth in animal-free conditions, fast and high-density growth in single-cell suspension, cell immortalization, and scalability. However, this study also reports preliminary nutritional profiles of the cells to address the specific applications.

MsNAC culture yields immortalized cells that are adaptable to animal-component free media

Cell immortalization (i.e., culturing of cells past their natural point of senescence) is important to ensure sufficient biomass can be produced and cells remain stable throughout the production process. Immortalization is typically achieved either through genetic manipulation or spontaneous immortalization through random mutations over many subcultures. While both methods have been used to generate cells for CM3,4,20, spontaneous immortalization may be favorable from a consumer acceptance and regulatory standpoint33. MsNACs were spontaneously immortalized and showed stable growth rates past 100 doublings, and a continuous cell culture has been maintained for over 1.5 years after isolation. Cultivation in animal-free conditions is necessary to align with the goals of CM to produce animal-derived products without the animal. Despite many advances in generating animal component-free media for mammalian7 and avian5 cells, animal-free media for CM remains an active area of research. MsNACs were easily adapted to commercial animal-component free media (SF900 III) over four passages and all further studies were performed in Sf900 III media. Cell culture without antimicrobials is also essential, as overuse of antimicrobials in traditional animal agriculture has led to the increase of antibiotic-resistant bacteria34. Further, use of antimicrobials in cell culture can mask low levels of contamination35. Although antimicrobials were used during cell isolation from embryos, they were removed after the fourth passage and subsequent experiments were conducted under antibiotic-free conditions. Due to the absence of Manduca sexta-specific cell markers, the exact cell type was not able to be determined. Instead, this study focused on further characterizing the cells based on functional traits relevant to cultivated meat.

MsNACs proliferate in high-density suspension culture

After a prolonged selection period for non-adherent cells, MsNACs were transferred to single-cell suspension growth in shake flasks. Single-cell suspension is preferable over adherent growth (either in static culture in flasks or microcarrier methods in dynamic culture) because cells can typically reach higher densities as they are no longer constrained by vessel or carrier surface area12. High-density suspension culture without microcarriers is often inhibited by the formation of large aggregates. Although biofilms and some cell aggregations were observed at the endpoint of culture in shake flasks, this did not seem to significantly impact cell growth. This is likely due to the long selection period for anchorage-independent cells. Passaging of cells in suspension was simply performed by diluting the culture, without removing spent media or breaking up cellular aggregates with enzymatic methods as may be necessary with other single-cell suspension lines used for cultivated meat5.

One important metric for optimization in CM is the highest achievable cell density. Increasing the cell density (as measured in cells per mL of media) results in less media and electricity usage per unit of cell biomass, thus reducing costs21. MsNACs reached an average of ~ 27E6 viable cells/mL at passage 35 and ~ 20E6 viable (~ 30E6 total) cells/mL at passage 50 after cryopreservation without further media or growth optimization. Other insect cells also reach similar densities in single-cell and animal-component free formulations. For example, Sf9 cells reached 14E6 cells/mL in 100-ml Erlenmeyer shake flasks36, 16E6 cells/mL in 50-mL TubeSpin bioreactors37, and 12-14E6 cells/mL in 1–5 L shake flasks38. Sf9 cells in a 14-L airlift bioreactor reached 10E6 cells/mL in an earlier formulation of Sf900 III media39. Thus, MsNACs show slightly higher achievable cell densities than high-density insect cell cultures previously reported, demonstrating consistency of insect cells from different species and starting tissues/developmental timepoints to reach high density single-cell suspension in animal-free media.

Further optimization should lead to even higher achievable cell densities. For example, Sf9 cells (the result of a clonal isolation, or separation of heterogeneous cell populations into single cells and propagation of genetically identical clonal populations) can reach approximately double the cell densities of their parent cell line, Sf21 38. It is also important to note that while MsNAC cell doubling time during log phase is comparable to other insect cell lines as well as to vertebrate cell lines cultured in suspension, the values were slower than optimized cell lines such as High-Five or Sf9 with doubling times as low as 18 h36. As density increased, cell growth rates slowed considerably. Because we observed glutamate depletion and ammonia buildup at densities above 3-4 M/mL without media exchange, the slow growth of our high-density cultures was likely due to waste accumulation, nutrient gradients, and altered metabolism. If MsNACs were to be considered for larger-scale culture, growth rates (especially at high density) would need to be optimized, potentially via clonal isolations, media optimization, or genetic engineering.

To our knowledge, the cell type with the highest published cell density in single-cell suspension studied for CM is an embryonic chicken fibroblast cell line, which reached 7E6 viable cells/mL in fed-batch culture with glucose supplemented daily5. This yield increased substantially by using a continuous (perfusion) culture system, with cells reaching an impressive 108E6 cells/mL after 15 days5. While perfusion was not explored in the present study, we expect that optimization of feeding strategies could enhance yield. Thus, MsNAC growth without optimization was comparable to spontaneously immortalized chicken fibroblasts similar to those used in USDA and FDA-approved CM products. One major difference between MsNAC and traditional CM products, however, are the environmental conditions for growth. Where avian or mammalian cells require 37 –39 °C incubation temperatures with CO2 supplementation, MsNACs were grown at 27 °C without CO25. These growth conditions are typical for insect cells, which have been routinely grown in adjacent industries in 50-liter wave bioreactors, 14 and 21-liter airlift bioreactors, or even retrofitted 150-liter microbial fermenters39,40,41,42,43. Biotechnology companies likely scale over 1000-liter bioreactors, although results are not published in peer-reviewed journals44. This precedent positions insect cells (such as MsNACs) well for large-scale production for CM.

Spent media offers insights into cell metabolism

Spent media analysis of MsNACs in batch culture was used to gain insights into metabolism and potential avenues for further optimization. Glucose was assumed to be the primary energy source for insect cells via glycolysis and cellular respiration13. In animal cell culture, the consumption of glucose is typically linked with the production of lactate as a waste product during anaerobic metabolism. Interestingly, during 7 days of culture (with growth slowing at around day 5), glucose was not consumed, and lactate was minimally produced, indicating that the cells were not relying on glycolysis as a primary energy source despite the relatively high levels of glucose (~ 9 g/liter) present in the media. This contrasts with typical insect cell metabolism. Although Sf9 cells can consume non-glucose carbohydrates such as maltose or fructose36, if glucose is present both Sf9 and High-Five cells exhaust it as a carbon source45,46. Insect cells produce significantly lower levels of lactate in comparison with mammalian cells46, although High-Five cells have been shown to produce lactate up to 16 mM in suspension. It is hypothesized that this accumulation is due to aggregate formation (and therefore low-oxygen environments for cells) as High-Five cells grown in single-cell suspension do not accumulate this level of lactate47,48,49. Thus, MsNACs show an altered metabolic pathway for energy production compared with commonly used insect cell lines and further exploration into this metabolic phenomenon is warranted.

In addition to glucose and lactate, the amino acids glutamine and glutamate, along with their metabolic byproduct ammonia were assessed. Although insect (and mammalian) cells are able to biosynthesize glutamine, making it a nonessential amino acid, glutamine is considered essential in many cell culture systems because glutamine consumption rate exceeds the biosynthesis rate50,51. Glutamine plays a vital role as the primary nitrogen donor for amino acid and nucleotide syntheses, undergoing conversion to glutamate and subsequently to alpha-ketoglutarate before entering the TCA cycle. The deamination of glutamine to glutamate and further to alpha-ketoglutarate results in the release of ammonia. The buildup of ammonia (alongside lactate) is toxic to cells, necessitating media refreshment to sustain continual cell growth52.

Metabolic waste buildup is one of the biggest limiting factors for large-scale biopharmaceutical production – with 2–10 mM ammonia and ~ 20–100 mM lactate inhibitory levels for mammalian cells21. Models of Chinese Hamster Ovary cells using these inhibitory levels and the production levels with metabolically optimized cells is still hypothesized to lead to culture systems that prohibit an economically sufficient cell density for CM21. Surprisingly, MsNACs consumed minimal glutamine over 7 days, but still produced significant amounts (up to 15 mM) of ammonia. In contrast, glutamate was nearly exhausted from the medium over 7 days and was likely the source of the ammonia production. Again, nutrient consumption patterns of MsNACs appear to differ from commonly used insect cell lines such as Sf9 cells, which are known to consume high levels of glutamine53,54. For example, Sf9 cells cultured in SF900 III media had the highest specific consumption rate for glutamine of nutrients studied in stirred tank culture and produced a maximum of 6.1 mM ammonia – nearly half the amount produced by MsNACs46. Because MsNACs were negatively affected by ammonia concentrations above 6.25 mM, we hypothesize that the rapid accumulation of ammonia is at least partially responsible for the cessation of growth.

In an effort to reduce ammonia production and further understand MsNAC metabolism, preliminary experiments were performed in SF900 III media with reduced amounts of glutamine. When glutamine was reduced to ~ 0.3 mM, the cells produced less ammonia and reached similar maximum VCDs compared with cells grown in control media (which contains ~ 14 mM glutamine) (SI Fig. 3F, G). While further optimization is necessary to understand how to further increase batch-culture VCD, the observation that MsNACs can proliferate with significantly reduced glutamine is favorable in the context of CM. An entomoculture-based TEA showed that in multiple media formulations L-glutamine is an order of magnitude more costly than glutamate22. Glutamine is also known to easily break down when stored for long periods of time, releasing inhibitory ammonia into the media. While a stabilized version of L-glutamine is used in many mammalian culture systems (l-alanyl-l-glutamine), insect cells have difficulty metabolizing l-alanyl-l-glutamine, therefore L-glutamine is still the preferred substrate in commercial media (ThermoFisher, personal communication). Because of this breakdown of glutamine, plant hydrolysates are hypothesized to be incomplete amino acid sources21. A 2021 TEA suggested that soybean meal could be a source of all essential amino acids for mammalian cell culture, except for glutamine and tyrosine. However, this meal produced more than double the required glutamate, and thus could be explored as a potential media supplement for MsNACs21. MsNACs were also able to proliferate and reach similar VCD to control media with both glutamine and glucose reduced media (0.1 g/L and 0.5 mM, respectively) (SI Fig. 3F). These results show the adaptability of the cells to growth on different substrates, representing the potential for further media optimization that should be explored in future work.

Ingredients for CM are assessed not only for their monetary cost, but also their environmental cost to produce and their availability to access at scale. Unfortunately, due to the proprietary nature of the cell culture media in this study we cannot determine the environmental cost and availability of all components in the media. It is important to note that commercial insect media formulations such as the SF900 III media used in this study are designed for insect cells that are producing recombinant proteins. The increased metabolic burden of protein synthesis leads to increased energy consumption, meaning the media likely contains an excess of nutrients than needed for cell growth vs. optimized recombinant protein production36. Future studies should explore customized media for MsNACs using only the nutrients necessary for growth to increase efficiency and decrease cost – for example, using design-of-experiments to create optimized formulations55. The ideal media formulation would primarily rely on plant or fungal hydrolysates instead of individually produced amino acids, as the high cost of amino acids are prohibitory to large-scale production21. For example, rapeseed proteins and peptides (a byproduct of canola oil production) have also been shown to increase Sf9 cell density by 60% in serum-free conditions56, and have been explored in mammalian cells as a low-cost serum-free media supplement57.

Nutrition

Proximate analysis

In addition to growth kinetics, adaptability to different culture vessels, and spent media analysis, a basic nutritional profile was compiled for MsNACs including proximate analysis as well as amino acid, mineral, and fatty acid composition. One of the advantages of the ability to easily scale to a 2.4-liter bioreactor was the feasibility of generating sufficient biomass (15–20 g of wet cell weight per bioreactor run) for food composition assays. These samples were used for proximate analysis to determine the proportion of protein, fat, carbohydrates, and ash in each batch of cells. These analyses showed that the dry weight nutritional breakdown of MsNACs was similar to FDA and USDA-approved embryonic chicken fibroblasts. Results can also be put in context of other alternative protein sources: whole-insect powders or “flours” are gaining popularity, with the most common ones coming from mealworms or crickets. Dry weight proximate analysis shows that protein content from these powders are lower than MsNACs, with 65.5 +/- 0.5% and 66 +/- 0.3% for cricket and mealworm, respectively58. The higher protein content in MsNAC dry weight compared with insect powders may be because of the lack of chitinous exoskeleton from whole insects, indicating that pure embryonic cell biomass may be more efficient for protein production than whole insects. Plant-based protein sources from fava beans and yellow pea concentrates have even lower protein content, at 62.5 +/- 0.6% and 55.1 +/- 1.2%, respectively58. Future studies should include analysis of the in vitro protein digestibility to ensure that the protein is bioavailable58.

Amino acids

Beyond proximate analysis, separate samples were analyzed for amino acid breakdown compared with DF-1 (embryonic chicken fibroblast) cells. While the overall breakdown was similar, DF-1 cells cultured in-house had increased molar concentrations of lysine, threonine, and valine. One 20-gram wet cell weight sample was also analyzed via acid hydrolysis and compared with cultivated embryonic chicken fibroblasts from two companies as well as their published values of conventional chicken. Again, overall amino acid breakdown was similar when analyzed as percentage of total amino acids reported. Unfortunately, lysine was not analyzed with the acid hydrolysis method and further analysis on the high lysine content of DF-1s compared with MsNACs found via LC-MS/MS should be pursued.

Minerals

Mineral content was also analyzed, as meat is an important source of essential minerals which are necessary nutrients to support cell function and growth59. Minerals can also contribute to the taste, texture, and appearance of meat products59. Interestingly, MsNACs had significantly more iron and calcium and increased, but not significant, levels of zinc, copper, magnesium, and phosphorus compared with DF-1 cells. These data are consistent with whole-animal nutritional analysis that shows insects are a good source of these minerals58,60,61. Just as mineral composition of whole animals largely depends on diet, cell-based mineral content will be influenced by media composition as well as cells’ ability to uptake each mineral. The animal-free SF900 III media therefore showed favorable mineral composition, with MsNACs able to uptake each mineral analyzed with equal or higher concentrations compared with DF-1 cells. This data is consistent with previous research using a Drosophila (fruit fly) cell line, which showed that when adjusting for cell size, insect cells had more iron and zinc compared with a mammalian (mouse myoblast) cell line. This research also found that using iron-fortified serum increased iron density in Drosophila cells19. While serum should be avoided, similar mineral fortification could be pursued if one wanted to nutritionally enhance MsNACs, for example with iron-fortified yeast extract62. While initial results are promising, further analysis on the bioavailability of MsNAC minerals compared with whole insects (or other meat sources) is warranted, as the exact source of the iron is unclear because the SF900 III formulation is proprietary. Although many minerals are essential to a healthy diet, accumulation of heavy metals are a growing concern for consumption of whole insects for food and feed, where insects sequester toxic heavy metals from feeding on agricultural waste63. While exposure to low levels of heavy metals such as lead, mercury, chromium, cadmium, and arsenic are inevitable, food must be closely monitored to avoid metal poisoning64. The high level of control in cell culture can decrease the risk of heavy metal accumulation – unsurprisingly, there were no detectable levels of the heavy metals included in our analyses of MsNACs (lead, arsenic, and cadmium).

Fatty acids

Finally, fatty acid content was analyzed and compared between DF-1 and MsNACs. Fatty acid data here is likely less relevant for both DF-1 and MsNACs, which are undifferentiated cells intended to be the animal protein in a product that would likely be supplemented with either plant-based fats or a different lipid-accumulating cell. Although not explored here, embryonic M. sexta cells have been investigated as a cultured fat source using a soybean oil emulsion to induce lipid accumulation – it is likely that MsNACs would be able to uptake lipids in a similar manner and could act as a fat source20. Although the data showed high variability, the majority of free fatty acids were not significantly different between the two cell types. The MsNACs generally had higher lysophosphatidylcholine and the DF-1s had higher phosphatidylcholines, representing differences in the insect and chicken cell membrane composition. Because phospholipids are responsible for the majority of meat-specific flavor, further investigation into potential differences in flavor between MsNAC and DF-1 (and other CM or meat sources) is warranted65,66.

Nutrition caveats

Although comparisons between DF-1 cells and MsNACs were intended to put nutritional data in context, it is important to note that comparisons between cell types are difficult due to cultivation in different media (DF-1 cells were cultured in media containing 10% FBS) which may impact the nutritional profile. Overall, it is difficult to determine how MsNACs may compare to other CM cell types based on limited and conflicting nutritional data and variability in culture conditions. Further, MsNACs are not intended to be a “complete” product, rather a potential ingredient and proof-of-concept that insect cells have favorable baseline nutritional properties that are on-par with currently the only FDA and USDA-approved cell type. We envision that MsNACs or similar insect cell lines may be valuable to the CM industry combined with plant-based products to provide animal nutrition and taste for human consumption.

Limitations and future work

Many additional improvements could be pursued to further characterize and engineer MsNACs. This could include altering media formulations, genetic engineering, or clonal isolations to select for even faster-growing cells that reach higher densities. Growth in bioreactors larger than 10 L should also be pursued to ensure cells can be scaled effectively. Nutrition could be enhanced by media supplementation or use of the baculovirus expression system to increase protein content or express specific nutrients18. Further studies are also required to assess the bioavailability of MsNAC nutrients compared with traditional meat. Larger scale culture also allows for more robust flavor/sensory analysis, which could include analysis of volatile compounds through GC-MS or sensory panels with human participants.

Beyond further engineering and characterization of MsNACs, it is important to consider potential biases in the cell line development process. Here, we described selection for three main traits that are favorable for CM during the expansion of MsNACs: (1) cells that grow well in animal component-free media, (2) cells that grow in single-cell suspension, and (3) cells that naturally spontaneously immortalize. Each selective pressure likely led to cultivation of a subpopulation of cells that is not representative of the originally isolated population. Although these selective pressures led to a robust cell line with stable growth over 1.5 years, it is possible that other desirable traits were lost in the process.

Starting from an embryonic cell population provides significant flexibility in selection criteria because many different early-stage cell types are present. Other selection criteria could include cells that grow in higher densities, in simpler media formulations, at lower temperatures, or cells that are more metabolically favorable (e.g., produce less ammonia or are less sensitive to ammonia). Future studies could even use clonal isolations to determine the most nutritious or palatable cell line.

Finally, consumer acceptance studies will need to be performed to determine the attitude of consumers towards cultured insect protein incorporation into their diet. Previous work has shown that Western consumers rate dishes that contain visible insects poorly (e.g., “fried mealworm” or “locust salad”), while disguised insect material (e.g., “pizza containing protein derived from insects”) were rated higher67. Thus, with appropriate marketing, insect CM could bypass Western consumers’ food neophobia associated with entomophagy. Cells could also be sourced from insect species that are that are more commonly consumed globally, such as crickets or mealworms18. If consumer acceptance proves too difficult, insect cells could also be incorporated into pet food (which accounts for approximately 20% of global meat consumption68) or as a protein source for animal feed supplementation69.

Conclusions

The present study provides a strategy to generate insect cells that are spontaneously immortalized, grow in animal-component free media, and proliferate in high densities in single-cell suspension culture in multiple different culture vessels; all of which remain active challenges in scaling up CM production. The nutritional composition of the cells was also investigated and was comparable to embryonic chicken fibroblasts. While consumer acceptance of insect cell-based cultured meat may be a challenge in Western communities, this study offers insight into how insect cells may be incorporated into large-scale cultivated meat production processes with potentially lower production costs yet comparable nutritional benefit.

Data availability

The authors declare that data supporting this study are available within Supplementary information. Extra data are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Abbreviations

- MsNAC:

-

Manduca sexta non-adherent cells

- CM:

-

Cultivated Meat

- VCD:

-

Viable Cell Density

- FBS:

-

Fetal Bovine Serum

References

Godfray, H. C. J. et al. Meat consumption, health, and the environment. Science 361, eaam5324 (2018).

Qiu, L. U.S. approves the sale of lab-grown chicken. The New York Times (2023).

Saad, M. K. et al. Continuous Fish Muscle Cell Line with Capacity for Myogenic and Adipogenic-like Phenotypes. 2022.08.22.504874 Preprint at https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.08.22.504874 (2022).

Stout, A. J. et al. Immortalized bovine Satellite cells for cultured meat applications. ACS Synth. Biol. 12, 1567–1573 (2023).

Pasitka, L. et al. Spontaneous immortalization of chicken fibroblasts generates stable, high-yield cell lines for serum-free production of cultured meat. Nat Food 4, 35–50 (2023).

Messmer, T. et al. Single-cell analysis of bovine muscle-derived cell types for cultured meat production. Front Nutr 10, 1212196 (2023).

Stout, A. J. et al. Simple and effective serum-free medium for sustained expansion of bovine satellite cells for cell cultured meat. Commun Biol 5, 1–13 (2022).

Bodiou, V., Moutsatsou, P. & Post, M. J. Microcarriers for upscaling cultured meat production. Frontiers in Nutrition 7, (2020).

Hanga, M. P. et al. Scale-up of an intensified bioprocess for the expansion of bovine adipose-derived stem cells (bASCs) in stirred tank bioreactors. Biotechnology and Bioengineering 118, 3175–3186 (2021).

Chapman, A. Numbers of Living Species in Australia and the World. (Australian Government Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage, and the Arts, 2009).

Law, J. H., Ribeiro, J. M. & Wells, M. A. Biochemical insights derived from insect diversity. Annu Rev Biochem 61, 87–111 (1992).

Rubio, N., Fish, K. D., Trimmer, B. A. & Kaplan, D. L. Possibilities for Engineered Insect tissue as a Food source. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems 3, 24 (2019).

Drugmand, J.-C., Schneider, Y.-J. & Agathos, S. N. insect cells as factories for biomanufacturing. Biotechnology Advances 30, 1140–1157 (2012).

Cox, M. M. J. & Hollister, J. R. FluBlok, a next generation influenza vaccine manufactured in insect cells. Biologicals 37, 182–189 (2009).

Schiller, J. T., Castellsagué, X., Villa, L. L. & Hildesheim, A. An update of prophylactic human papillomavirus L1 virus-like particle vaccine clinical trial results. Vaccine 26, K53–K61 (2008).

Pijlman, G. P. et al. Relocation of the attTn7 Transgene Insertion Site in Bacmid DNA Enhances Baculovirus Genome Stability and Recombinant Protein Expression in Insect Cells. Viruses 12, (2020).

World Health Organization. Interim recommendations for use of the Novavax NVX-CoV2373 vaccine against COVID-19: interim guidance, 20 December 2021. https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/350881 (2021).

Verkerk, M. C., Tramper, J., van Trijp, J. C. M. & Martens, D. E. Insect cells for human food. Biotechnology Advances 25, 198–202 (2007).

Rubio, N., Fish, K., Trimmer, B. & Kaplan, D. In Vitro Insect muscle for tissue Engineering Applications. ACS Biomaterials Science & Engineering 5, 1071–1082 (2019).

Letcher, S. M. et al. In vitro insect Fat Cultivation for Cellular Agriculture Applications. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 8, 3785–3796 (2022).

Humbird, D. Scale-up economics for cultured meat. Biotechnology and Bioengineering 118, 3239–3250 (2021).

Ashizawa, R. et al. Entomoculture: a preliminary Techno-Economic Assessment. Foods 11, 3037 (2022).

Dorn, A., Bishoff, S. T. & Gilbert, L. I. An incremental analysis of the Embryonic Development of the Tobacco Hornworm, Manduca sexta. International Journal of Invertebrate Reproduction and Development 11, 137–157 (1987).

Gershman, A. et al. De novo genome assembly of the tobacco hornworm moth (Manduca sexta). G3 Genes|Genomes|Genetics 11, jkaa047 (2021).

Baryshyan, A. L., Woods, W., Trimmer, B. A. & Kaplan, D. L. Isolation and maintenance-free culture of contractile myotubes from Manduca sexta Embryos. PLoS ONE 7, e31598 (2012).

Zheng, J., Johnson, M., Mandal, R. & Wishart, D. S. A Comprehensive targeted Metabolomics Assay for Crop Plant Sample Analysis. Metabolites 11, 303 (2021).

Foroutan, A. et al. The Bovine Metabolome. Metabolites 10, 233 (2020).

Foroutan, A. et al. Chemical composition of commercial cow’s milk. J Agric Food Chem 67, 4897–4914 (2019).

Failla, M., Hopfer, H. & Wee, J. Evaluation of public submissions to the USDA for labeling of cell-cultured meat in the United States. Front Nutr 10, 1197111 (2023).

Hashimoto, Y., Zhang, S. & Blissard, G. W. Ao38, a new cell line from eggs of the black witch moth, Ascalapha odorata (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae), is permissive for AcMNPV infection and produces high levels of recombinant proteins. BMC Biotechnology 10, 50 (2010).

Stavroulakis, D. A., Kalogerakis, N., Behie, L. A. & Latrou, K. Kinetic data for the BM-5 insect cell line in repeated-batch suspension cultures. Biotechnology and Bioengineering 38, 116–126 (1991).

Beas-Catena, A., Sánchez-Mirón, A., García-Camacho, F. & Molina-Grima, E. Adaptation of the Se301 insect cell line to suspension culture. Effect of turbulence on growth and on production of nucleopolyhedrovius (SeMNPV). Cytotechnology 63, 543–552 (2011).

Bryant, C., van Nek, L. & Rolland, N. C. M. European Markets for cultured meat: a comparison of Germany and France. Foods 9, 1152 (2020).

Mathew, A. G., Cissell, R. & Liamthong, S. Antibiotic resistance in bacteria associated with food animals: a United States perspective of livestock production. Foodborne Pathog Dis 4, 115–133 (2007).

Cobo, F. et al. Microbiological control in stem cell banks: approaches to standardisation. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 68, 456–466 (2005).

Käßer, L., Harnischfeger, J., Salzig, D. & Czermak, P. The effect of different insect cell culture media on the efficiency of protein production by Spodoptera frugiperda cells. Electronic Journal of Biotechnology 56, 54–64 (2022).

Xie, Q. et al. TubeSpin bioreactor 50 for the high-density cultivation of Sf-9 insect cells in suspension. Biotechnol Lett 33, 897–902 (2011).

Cronin, C. N. High-volume shake flask cultures as an alternative to cellbag technology for recombinant protein production in the baculovirus expression vector system (BEVS). Protein Expr Purif 165, 105496 (2020).

King, G. A., Daugulis, A. J., Faulkner, P. & Goosen, M. F. Recombinant beta-galactosidase production in serum-free medium by insect cells in a 14-L airlift bioreactor. Biotechnol Prog 8, 567–571 (1992).

Garnier, A. et al. Dissolved carbon dioxide accumulation in a large scale and high density production of TGFβ receptor with baculovirus infected Sf-9 cells. Cytotechnology 22, 53–63 (1996).

Ghasemi, A., Bozorg, A., Rahmati, F., Mirhassani, R. & Hosseininasab, S. Comprehensive study on Wave bioreactor system to scale up the cultivation of and recombinant protein expression in baculovirus-infected insect cells. Biochemical Engineering Journal 143, 121–130 (2019).

Kaiser, S. C., Decaria, P. N., Seidel, S. & Eibl, D. Scaling-up of an insect cell-based Virus production process in a Novel single-use bioreactor with flexible agitation. Chemie Ingenieur Technik 94, 1950–1961 (2022).

Maiorella, B., Inlow, D., Shauger, A. & Harano, D. Large-scale insect cell-culture for recombinant protein production. Nat Biotechnol 6, 1406–1410 (1988).

Drugmand, J.-C. Characterization of insect cell lines is required for appropriate industrial processes: Case Study of High-Five Cells for Recombinant Protein Production. Chemistry & \ldots (2007).

Rhiel, M., Mitchell-Logean, C. M. & Murhammer, D. W. Comparison of Trichoplusia ni BTI-Tn-5B1-4 (high five™) and Spodoptera frugiperda Sf-9 insect cell line metabolism in suspension cultures. Biotechnology and Bioengineering 55, 909–920 (1997).

Guardalini, L. G. O. et al. Sf9 cell metabolism throughout the recombinant baculovirus and rabies virus-like particles production in two Culture systems. Mol Biotechnol (2023) doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s12033-023-00759-2.

Yang, J.-D. et al. Rational scale-up of a baculovirus-insect cell batch process based on medium nutritional depth. Biotechnology and Bioengineering 52, 696–706 (1996).

Ikonomou, L., Schneider, Y.-J. & Agathos, S. N. Insect cell culture for industrial production of recombinant proteins. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 62, 1–20 (2003).

Ikononou, L., Bastin, G., Schneider, Y.-J. & Agathos, S. N. Design of an efficient medium for insect cell growth and recombinant protein production. In Vitro Cell.Dev.Biol.-Animal 37, 549–559 (2001).

Yoo, H. C., Yu, Y. C., Sung, Y. & Han, J. M. Glutamine reliance in cell metabolism. Exp Mol Med 52, 1496–1516 (2020).

Mitsuhashi, J. Determination of Essential Amino Acids For Insect Cell Lines. in Invertebrate Cell Culture Applications (eds. Maramorosch, K. & Mitsuhashi, J.) 9–51 (Academic Press, 1982). doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-470290-5.50007-1.

Hubalek, S., Melke, J., Pawlica, P., Post, M. J. & Moutsatsou, P. Non-ammoniagenic proliferation and differentiation media for cultivated adipose tissue. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology 11, (2023).

Bédard, C., Tom, R. & Kamen, A. Growth, Nutrient consumption, and End-Product Accumulation in Sf-9 and BTI-EAA insect cell cultures: insights into growth limitation and metabolism. Biotechnology Progress 9, 615–624 (1993).

Benslimane, C., Elias, C. B., Hawari, J. & Kamen, A. Insights into the Central Metabolism of Spodoptera frugiperda (Sf-9) and Trichoplusia ni BTI-Tn-5B1-4(Tn-5) insect cells by Radiolabeling studies. Biotechnology Progress 21, 78–86 (2005).

Saisud, S. et al. Development of an Animal-Derived Component-Free Medium for Spodoptera Frugiperda (Sf9) Cells Using Response Surface Methodology. https://www.researchsquare.com/article/rs-2437075/v1 (2023) doi:https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-2437075/v1.

Deparis, V. et al. Promoting effect of rapeseed proteins and peptides on Sf9 insect cell growth. Cytotechnology 42, 75–85 (2003).

Stout, A. J. et al. A Beefy-R culture medium: replacing albumin with rapeseed protein isolates. Biomaterials 296, 122092 (2023).

Stone, A. K., Tanaka, T. & Nickerson, M. T. Protein quality and physicochemical properties of commercial cricket and mealworm powders. J Food Sci Technol 56, 3355–3363 (2019).

Falowo, A. A Comprehensive Review of Nutritional Benefits of Minerals in Meat and Meat products. (2021) doi:https://doi.org/10.47262/SL/9.2.132021010.

Finke, M. D. Complete nutrient composition of commercially raised invertebrates used as food for insectivores. Zoo Biology 21, 269–285 (2002).

Montowska, M., Kowalczewski, P. Ł., Rybicka, I. & Fornal, E. Nutritional value, protein and peptide composition of edible cricket powders. Food Chemistry 289, 130–138 (2019).

Sabatier, M. et al. Iron bioavailability from fresh cheese fortified with iron-enriched yeast. Eur J Nutr 56, 1551–1560 (2017).

Malematja, E., Manyelo, T. G., Sebola, N. A., Kolobe, S. D. & Mabelebele, M. The accumulation of heavy metals in feeder insects and their impact on animal production. Science of the Total Environment 885, 163716 (2023).

Balali-Mood, M., Naseri, K., Tahergorabi, Z., Khazdair, M. R. & Sadeghi, M. Toxic mechanisms of five heavy metals: Mercury, lead, Chromium, Cadmium, and Arsenic. Front Pharmacol 12, 643972 (2021).

Huang, Y.-C., Li, H.-J., He, Z.-F., Wang, T. & Qin, G. Study on the flavor contribution of phospholipids and triglycerides to pork. Food Science and Biotechnology 2010 19:5 19, 1267–1276 (2010).

Igene, J. O. & Pearson, M. Role of phospholipids and triglycerides in warmed-over flavor development in meat model systems. Journal of Food Science 44, 1285–1290 (1979).

Schösler, H., Boer, J. de & Boersema, J. J. Can we cut out the meat of the dish? Constructing consumer-oriented pathways towards meat substitution. Appetite 58, 39–47 (2012).

Knight, A. The relative benefits for environmental sustainability of vegan diets for dogs, cats and people. PLOS ONE 18, e0291791 (2023).

Hancz, C., Sultana, S., Nagy, Z. & Biró, J. The role of insects in Sustainable Animal feed production for environmentally friendly agriculture: a review. Animals 14, 1009 (2024).

Acknowledgements

We thank New Harvest for their support of this work. We also thank the Metabolomics Innovation Center and Eurofins for assistance with nutritional testing, Chemometec for assistance with cell counting, and Ark Biotech for the support with bioreactor runs. Thank you to ThermoFisher for their generous donation of customized Sf900 III through their academic partnership program. Thanks also to Ellie Contreras for the donation of DF-1 cells, Naya McCartney for assistance with collecting Manduca sexta eggs for isolations, and Natalie Rubio for insect cell culture guidance. Thanks to Yu-Ting Dingle for education on Adobe Illustrator for figure preparation. Finally thank you to Tufts University Center for Cellular Agriculture past and present members Michael Saad, Adham Ali, Olympe Jean, and others for scientific input and support.

Funding

This work was supported by the New Harvest Graduate Fellowship Program and the United States Department of Agriculture (2021–05678).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.L. developed the study, conducted experiments, and drafted the manuscript. O.P. conducted experiments and edited the manuscript. H.C. conducted experiments and edited the manuscript. A.M. conducted experiments and edited the manuscript. B.T. developed the study and edited the manuscript. D.K. developed the study, edited the manuscript, and provided the funding.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Letcher, S.M., Calkins, O.P., Clausi, H.J. et al. Establishment & characterization of a non-adherent insect cell line for cultivated meat. Sci Rep 15, 7850 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86921-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86921-z