Abstract

Radiocontrast media is a major cause of nephrotoxic acute kidney injury(AKI). Contrast-enhanced CT(CE-CT) is commonly performed in emergency departments(ED). Predicting individualized risks of contrast-associated AKI(CA-AKI) in ED patients is challenging due to a narrow time window and rapid patient turnover. We aimed to develop machine-learning(ML) models to predict CA-AKI in ED patients. Adult ED patients who underwent CE-CT between 2016 and 2020 at an academic, tertiary, referral hospital were included. Demographic, clinical, and laboratory data were collected from electronic medical records. Five ML models based on logistic regression; random forest; extreme gradient boosting; light gradient boosting; and multilayer perceptron were developed, using 42 features. Among 22,984 ED patients who underwent CE-CT; 1,862(8.1%) developed CA-AKI. The LGB model performed the best (AUROC = 0.731). Its top 10 features, in order of importance for predicting CA-AKI, were baseline serum creatinine; systolic blood pressure; serum albumin; estimated glomerular filtration rate; blood urea nitrogen; body weight; serum uric acid; hemoglobin; triglyceride; and body temperature. Given the difficulty of predicting risk of CA-AKI in ED, this model can help clinicians with early recognition of AKI and nephroprotective point-of-care interventions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Acute kidney injury (AKI) is a major clinical problem affecting a significant number of patients globally, with high rates of mortality and morbidity1. Given the lack of validated injury markers, the diagnosis of AKI is often delayed because of the time lag between the onset of injury and functional decline2,3. Early recognition of AKI is particularly challenging in emergency department (ED) settings because of the narrow time window for clinical decisions and the quick discharge of many patients4,5. Even mild AKI in patients discharged from the ED is significantly associated with an increased risk of death or requirement of dialysis6,7.

AKI due to nephrotoxic exposure accounts for a substantial proportion of all AKI cases. In particular, iodinated radiocontrast media is a major source of nephrotoxicity8. Millions of intravascular contrast media procedures are annually performed in North America9, and computed tomography (CT) utilization within ED has been continuously increasing worldwide10. Although the true incidence of contrast-induced AKI (CI-AKI) has been a subject of debate due to variable definitions and many confounders affecting kidney function11,12, sufficient data support the negative impact of postcontrast AKI (contrast-associated AKI, CA-AKI) on short- and long-term outcomes13,14.

CA-AKI can be minimized using preventive strategies and hypervigilance8. A predictive approach to identifying AKI risk in ED patients who undergo contrast exposure may offer opportunities for clinical intervention, within a short window, and ensure inpatient or outpatient follow-up. This is particularly important in the ED, where intravenous contrast media for enhanced CT cannot be withheld given the clinical urgency15,16,17. However, considering the fast-paced ED workflow and narrow time window for clinical decision-making, accurately assessing the risk of CA-AKI development at an individual level, with sufficient context, is challenging. Thus, an automated and straightforward prediction tool that incorporates various clinical factors for objective clinical decision-making is needed. Considering the lack of real-time biomarkers for AKI detection and the emerging role of machine-learning in AKI prediction18,19, we tested models based on machine-learning and developed a prediction tool for CA-AKI in unselected ED patients who underwent contrast-enhanced CT (CE-CT).

Methods

This retrospective study was conducted in the ED of a tertiary urban academic medical center in Seoul, Korea, with two million outpatients annually and 1,975 inpatient beds. The ED has 69 beds, with an average annual patient volume of 75,000–80,000 patients. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Samsung Medical Center (IRB no. 2023–09–030). The requirement for informed consent was waived due to the use of de-identified data for analysis and the retrospective and observational design of the study. All methods were performed and reported in accordance with the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki and the ‘Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology’ guidelines20.

Study population

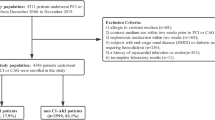

Patients who underwent CE-CT in the ED between January 2016 and December 2020 were identified using an electronic medical record (EMR) system. Patients who met the following criteria were excluded: (1) those aged < 18 years old; (2) with end-stage kidney disease on dialysis; and (3) those with missing data on serum creatinine levels needed for a CA-AKI diagnosis, both before and after CT.

Data collection

The EMR system used in this study is an internally developed system that was rolled out in July 2016, replacing the previous internally developed EMR. The new EMR is part of a hospital information system called Data Analytics and Research Window for Integrated kNowledge (DARWIN). DARWIN is a comprehensive system that contains computerized order entries from physicians; nurses; pharmacists; and billing and research support departments. It even includes patient portals and web services.

Patient characteristics, past diagnoses, prescription history, laboratory test records, and ED status during their visit were extracted from the Clinical Data Warehouse of the study site. Patient data included age, sex, weight, height, body mass index (BMI), whether they underwent angiography during their ED visit, and history of previous CT contrast exposure within three months prior to the ED visit. The International Classification of Disease codes for the past year were used to define comorbidities including diabetes mellitus, hypertension, heart failure, cancer, cardiac arrhythmia, liver cirrhosis, chronic kidney disease, kidney transplantation, and myocardial infarction. Prescription histories during the past year were collected. The collected medication records included angiotensin receptor blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, diuretics, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, chemotherapeutic agents, immunosuppressants, and aminoglycoside antibiotics.

The following laboratory data were collected: hemoglobin, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), serum creatinine, albumin, uric acid, sodium, potassium, chloride, low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, triglyceride (TG), urine albumin, urine protein to creatinine ratio, and urine albumin to creatinine ratio.

The initial status of the patients at the time of ED arrival was collected, focusing on trauma, sepsis, and the use of ambulance or transfer from another hospital. Severity was assessed using the Korean Triage and Acuity Scale (KTAS), and the AVPU scale. The vital signs (systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, pulse rate, respiration rate, body temperature, and O2 saturation) upon arrival were collected.

Definition of CA-AKI

CA-AKI was the primary outcome and was defined as either an absolute increase in serum creatinine of at least 0.5 mg/dL or a relative increase of at least 25% from the baseline within seven days of contrast administration21. Baseline creatinine levels were collected within 24 h of CT contrast exposure. If multiple assessments were conducted, the serum creatinine value closest to the time of CT was considered the baseline value. If creatinine levels within 24 h were missing, the median value of all creatinine levels measured in the three months prior to CT was considered the baseline value. The post-CT creatine level was defined as the highest creatinine level measured in the two to seven days following contrast exposure.

Statistical analysis

For descriptive analysis, continuous variables are presented in terms of the medians (interquartile range, IQR), and categorical variables are presented as counts and percentages. The Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare continuous variables, and the chi-square test was performed for categorical variables. P-values < 0.01 were considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using R version 4.2.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) and Python version 3.9.7.

Data preprocessing and model development

For the collected patient characteristics and clinical features, such as height, weight, and laboratory data, outliers were removed based on the clinical context. Categorical variables were processed using one-hot encoding, which created separate binary features for each category. Our dataset was randomly divided into an 80% development set and a 20% validation set. Missing data were imputed using multiple imputations by chained equations, as this exhibited the closest representation of the spread of the original data, compared with other imputation methods. We applied five machine-learning models: logistic regression (LR), random forest (RF), extreme gradient boosting (XGB), light gradient boosting (LGB), and multilayer perceptron (MLP). The hyperparameters were optimized using both random search and grid search with five-fold cross-validation.

We computed the optimal threshold using Youden’s J statistic for model evaluation. The performance of each algorithm was ranked according to the area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve (AUROC). Accuracy, sensitivity (recall), specificity, positive predictive value (PPV; precision), negative predictive value (NPV), and F1 score were calculated. The F1 score is the harmonic mean of precision and recall: F = 2 × Precision × Recall/(Precision + Recall). It provides better representation when dealing with an imbalanced dataset.

Model interpretation

Shapley additive explanation (SHAP) was used to interpret the results. SHAP uses a game-theoretic approach to evaluate how each feature contributes to and interferes with the model outcome. The SHAP values help identify the key features that significantly influence the model. The marginal contribution of each variable to the outcome variable was visualized using SHAP plots of individual cases22,23.

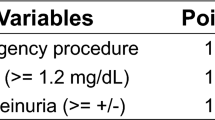

To understand the clinical relationship between significant features identified by unbiased machine-learning models, we additionally developed an AutoScore model24. AutoScore is a recently developed framework that uses RF plots to rank variables and generates clinical risk-scores. Each variable is automatically divided into interval ranges. The generated score table assigns a higher point on the variable range, which indicates a more significant contribution to the risk. The final score is the sum of all the breakpoints, and a higher final score indicates a higher risk of an outcome. The model provides area under the curves (AUC), sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV values as performance metrics.

Results

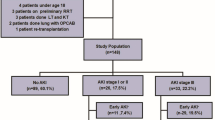

Among the 369,469 patients who visited our ED between 2016 and 2020; 110,845 patients who underwent CT scans during their visit were screened. After excluding pediatric patients; those with end-stage kidney disease; and those who did not receive contrast media; 51,837 patients with contrast exposure were identified. After further exclusion of the patients who did not have baseline or follow-up serum creatinine measurements; a total of 22,984 patients were included in the final analysis (Fig. 1), of whom 1862 (8.1%) developed CA-AKI.

Baseline characteristics

The baseline characteristics of the study participants are presented in Table 1. More patients in the CA-AKI group underwent CT angiography and had a history of prior exposure to CT contrast, compared with those in the no CA-AKI group. Ambulance arrivals and transfers from other hospitals were more common in the CA-AKI group. The proportions of patients with estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2 or eGFR ≥ 90 mL/min/1.73 m2, and proteinuria were higher in the CA-AKI group than in the no CA-AKI group. The patients in the CA-AKI group had more comorbidities including diabetes, hypertension, heart failure, and arrhythmia, and had more exposure to renin-angiotensin system blockers, diuretics, and chemotherapeutic agents, compared with those in the no CA-AKI group.

Model construction and comparison

Forty-two features were selected as inputs for the models to predict the risk of CA-AKI. We tested five machine-learning models in the training set, including LR, RF, XGB, LGB, and MLP. The training and test sets consisted of 18,387 (80%) and 4,597 (20%) patients, respectively, randomly selected from the full cohort (Fig. 2). The performance metrics of the five machine-learning models are presented in Table 2. Figure 3 shows the ROC curves. The LGB model achieved the best predictive effects for CA-AKI with an AUROC of 0.731, whereas the LR model exhibited the lowest performance.

Schematic of model development. AUROC, area under the receiver operating characteristic curve; EMR, electronic medical record; LGB, light gradient boosting; LR, logistic regression; RF, random forest; XGB, extreme gradient boosting; MLP, multi-layer perception; MICE, multiple imputation by chained equations.

Model interpretation

Figure 4 shows the feature importance in the LGB model. The features, in order of their feature importance, were serum creatinine, systolic blood pressure, serum albumin, eGFR, BUN, body weight, serum uric acid, hemoglobin, TG, body temperature, age, chief complaint, serum potassium, pulse rate, diastolic blood pressure, LDL, height, serum sodium, and serum chloride levels.

To explain the effect of each feature on the decision of the prediction model, we illustrated the individual contributions of the variables of our trained LGB model using SHAP. Figure 5A and Fig. 5B display the individual contributions of features to the SHAP plots for patients with and without CA-AKI, respectively. Baseline serum creatinine and albumin levels were the most critical predictive features for the model output. Systolic blood pressure and albuminuria were also important predictive factors for CA-AKI.

SHAP plots of LGB model, depicting the CA-AKI risk for two example patients. The red arrow represents the impact values that are positive while the blue represents negative. The length of the arrow bar represents the absolute value of the impact. CA-AKI, contrast-associated acute kidney injury; KTAS, Korean Triage and Acuity Scale; LGB, light gradient boosting; SHAP, Shapley additive explanation.

Furthermore, to obtain a more detailed understanding of the associations between CA-AKI and the main features identified by the unbiased machine-learning model, we built the AutoScore model. Seventeen variables were selected based on their identified prognostic value from the LGB model (baseline serum creatinine, systolic blood pressure, body weight, serum albumin, serum uric acid, age, hemoglobin, pulse rate, serum potassium, serum chloride, serum sodium, proteinuria, diuretic use, sex, sepsis, and diabetes). The scoring table for the AutoScore model is presented in Table 3. The final scores ranged from 0 to 17. The baseline serum creatinine concentration had the highest score. High systolic blood pressure (≥ 170 mmHg), hypoalbuminemia (≤ 2.4 g/dL), and hyponatremia (≤ 124 mmol/L) also had high scores (> 10). The other variables associated with higher scores were hyperuricemia (≥ 7.5), proteinuria, use of diuretics, and sepsis. The AUROC evaluated on the test dataset was 0.715 (95% confidence interval, 0.679–0.750).

Discussion

Among undiagnosed patients who underwent CE-CT for various indications in the ED of a tertiary hospital, 8.1% developed AKI after CT contrast exposure. We created a machine-learning-based prediction model that relied on 42 clinical parameters to predict the risk of CA-AKI. Among various models, the LGB model exhibited the best performance in our study. This model can be used as a personalized tool for identifying patients at higher risks of AKI development after CE-CT scans in the ED.

Considering the current lack of validated injury markers for AKI detection, AKI diagnosis relies on serum creatinine and urine output criteria, according to the current guidelines25. However, serum creatinine rises in a delayed fashion, and changes in urine output can be difficult to distinguish from physiological variations26. This often leads to a delay in AKI diagnosis and initiation of appropriate interventions26. Accordingly, early clinical recognition of AKI has been identified as an important target for EMR-based predictive modeling18,19. An early prediction tool for AKI could be particularly useful in ED settings, where treatment decisions are made before the clinical signs of AKI become apparent27. Early interventions have the potential to improve outcomes2,3and allow ED clinicians to make informed decisions regarding discharge planning and future treatment trajectories4,5.

Although several studies have reported CA-AKI predictive models using machine-learning algorithms28,29,30,31,32,33, no study has investigated predictive tools for CA-AKI in unselected ED-visiting populations. Few studies targeted patients who underwent CE-CT scans, and most previous studies were based on patients who underwent percutaneous coronary angiographies28,29,30,31,32,33. The present study is the first to demonstrate a predictive model of CA-AKI in ED patients who underwent intravenous CE-CT scans. We tested various machine-learning models, including LR, RF, XGB, LGB, and MLP. Among them, the LGB model exhibited the best performance.

Although the exact mechanism by which radiocontrast media contributes to AKI is not fully understood, widely accepted mechanisms include direct cytotoxicity to renal tubular epithelial cells and vasoconstrictive effects on renal microcirculation, leading to ischemic injury of the renal medulla34,35,36,37. Thus, patients under oxidative stress, vasoconstriction, and/or endothelial dysfunction are likely to have increased susceptibility to CI- or CA-AKI. In accordance with the consensus that preexisting kidney dysfunction is the most significant risk factor for CI-AKI38, baseline serum creatinine concentrations had the highest feature importance in our model, as expected. Systolic blood pressure had the second-highest feature importance, followed by baseline creatinine levels. This trend was consistently observed in our AutoScore model, showing a positive correlation between blood pressure and scores, which aligns with data from a recent meta-analysis39. Given the vasoconstrictive effect of contrast media that leads to medullary hypoxia35,40, microcirculation impairment due to damaged renal arterioles and endothelial dysfunction in patients with hypertension might have exacerbated existing susceptibility to medullary hypoxia. The serum albumin level was also a strong predictive factor in our model. Previous epidemiologic studies have consistently reported an inverse relationship between serum albumin concentrations and AKI risk; in a previous systematic review41, the risk of CA-AKI was 2.6-fold higher in patients with hypoalbuminemia42. However, it is uncertain whether hypoalbuminemia is a contributing factor for CA-AKI or has a role as a surrogate marker of malnutrition and severity of illness. The effect of exogenous albumin pre-infusion in patients with hypoalbuminemia who undergo CE-CT scans could be a topic of future studies.

Risk prediction tools for CA-AKI are possibly unsuitable for decision-making regarding the deferral of contrast use43. Contrast exposure may not be the sole etiology for many CA-AKI cases, and uncertain causal relationships between contrast exposure and postcontrast status have been reported38,44,45. Particularly in ED settings, where CE-CTs are performed urgently as a life-saving diagnostic procedure, a delay in diagnosis and treatment due to withholding CE-CT would increase the risk of mortality and long-term complications in patients15,17. The benefits of using radiocontrast often outweigh its risks in many ED cases16. Therefore, this predictive tool could be used for identifying patients who need more intensive nephroprotective measures, such as hemodynamic stabilization, volume status optimization, early glycemic control, and avoidance of nonessential nephrotoxic medication, as well as serial measures of kidney function25,26. Given the low outpatient follow-up rates after contrast exposure46and the poorer outcomes observed in patients with AKI discharged from ED6,7, this predictive model can be valuable for informed decision-making. Low-risk patients may be eligible for early discharge, while high-risk patients can be scheduled for close follow-up of kidney function. Although there are no proven effective medications for CI-AKI, volume expansion with intravenous crystalloid infusion can reduce the risk of CA-AKI. Studies suggest that larger volume expansions (e.g., 1.6 L over 17 h) lead to greater risk reduction in CA-AKI9,47. This highlights the potential benefit of delaying the discharge of patients with high risk for CA-AKI, and allowing for extended periods of intravenous volume infusion, unless this is contraindicated by volume overload. We believe that our predictive tool can aid in identifying these high-risk patients for intravenous volume infusion, optimizing resource utilization.

The current study has several limitations. First, although the sample size was substantial, the single-center nature of the study limits generalizability, as our patient population was primarily Asian. Moreover, the severities of the illnesses were relatively high, with a greater prevalence of comorbidities such as malignancy, reflecting the nature of our academic tertiary referral hospital. Future studies are warranted to validate the present predictive model using different patient cohorts. Second, our model did not account for the volume of contrast media used during CT, which affects AKI risk. Additionally, many patients with preexisting kidney impairment received pre- and post-hydration with intravenous crystalloid fluids as a preventative measure for CA-AKI, as per hospital protocol. The volume and duration of the infusions may have influenced outcomes as effect modifiers; however, we did not incorporate this aspect into our model. Finally, there may have been other contributing factors in AKI development in many patients categorized as having CA-AKI. Our data did not allow us to determine whether exposure to contrast media was the main causative factor of AKI (CI-AKI). As our study cohort exclusively included patients who underwent CE-CT scans, without an unexposed control group in the dataset, we could not directly assess the independent contributions of other AKI-associated risk factors outside the context of contrast exposure. While our machine-learning model incorporated these variables during training and interpretation, it did not establish causality or differentiate the impact of contrast media from potential confounders. However, real-world AKI scenarios often involve multiple and overlapping etiologies48. Thus, our model prioritized the identification of patients who are likely to develop AKI after contrast exposure over the precise recognition of AKI cases solely caused by contrast media (CI-AKI).

Conclusion

Machine-learning models using EMR data were developed to identify ED patients at high risk of developing CA-AKI. Considering the difficulties associated with predicting CA-AKI development in ED settings; our model can potentially improve the outcomes of ED patients who undergo CE-CT scans and high-risk patients with CA-AKI, through the application of an AKI-specific point of care.

Data availability

Data were obtained from the Clinical Data Warehouse at the study site. The datasets generated and analyzed in the current study are not publicly available because the dataset includes, although de-identified, part of the patient information, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AKI:

-

Acute kidney injury

- AUC:

-

Area under the curves

- AUROC:

-

Area under the receiver operating characteristic curve

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- BUN:

-

Blood urea nitrogen

- CA-AKI:

-

Contrast-associated acute kidney injury

- CDW:

-

Clinical data warehouse

- CE-CT:

-

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography

- CI-AKI:

-

Contrast-induced acute kidney injury

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- DARWIN:

-

Data Analytics and Research Window for Integrated kNowledge

- ED:

-

Emergency department

- eGFR:

-

Estimated glomerular filtration rate

- EMR:

-

Electronic medical record

- IRB:

-

Institutional review board

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range

- KTAS:

-

Korean Triage and Acuity Scale

- LDL:

-

Low-density lipoprotein

- LGB:

-

Light gradient boosting

- LR:

-

Logistic regression

- MICE:

-

Multiple imputation by chained equations

- MLP:

-

Multilayer perceptron

- NPV:

-

Negative predictive value

- PPV:

-

Positive predictive value

- RF:

-

Random forest

- ROC:

-

Receiver operating characteristic

- SHAP:

-

Shapley additive explanation

- TG:

-

Triglyceride

- XGB:

-

Extreme gradient boosting

References

Hoste, E. A. J. et al. Global epidemiology and outcomes of acute kidney injury. Nat Rev Nephrol 14, 607–625 (2018).

Waikar, S. S. & Bonventre, J. V. Creatinine kinetics and the definition of acute kidney injury. J Am Soc Nephrol 20, 672–679 (2009).

Endre, Z. H., Pickering, J. W. & Walker, R. J. Clearance and beyond: the complementary roles of GFR measurement and injury biomarkers in acute kidney injury (AKI). Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 301, F697-707 (2011).

Cairns, C. & Kang, K. National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2021 emergency department summary tables., https://ftp.cdc.gov/pub/Health_Statistics/NCHS/ (2021).

Greenwald, P. W. et al. The ED as the primary source of hospital admission for older (but not younger) adults. Am J Emerg Med 34, 943–947 (2016).

Acedillo, R. R. et al. Characteristics and Outcomes of Patients Discharged Home from an Emergency Department with AKI. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 12, 1215–1225 (2017).

Scheuermeyer, F. X. et al. The Clinical Epidemiology and 30-Day Outcomes of Emergency Department Patients With Acute Kidney Injury. Can J Kidney Health Dis 4, 2054358117703985 (2017).

Nash, K., Hafeez, A. & Hou, S. Hospital-acquired renal insufficiency. Am J Kidney Dis 39, 930–936 (2002).

Media, A. C. o. D. a. C. ACR Manual On Contrast Media, 2023).

Bellolio, M. F. et al. Increased Computed Tomography Utilization in the Emergency Department and Its Association with Hospital Admission. West J Emerg Med 18, 835–845 (2017).

Lee, C. D., Hinson, J. & Davenport, M. S. Avoiding Contrast-Enhanced Imaging to Prevent Contrast-Induced Acute Kidney Injury. N Engl J Med 387, 1809–1812 (2022).

Kashani, K., Levin, A. & Schetz, M. Contrast-associated acute kidney injury is a myth: We are not sure. Intensive Care Med 44, 110–114 (2018).

Lakhal, K. et al. Acute Kidney Injury Network definition of contrast-induced nephropathy in the critically ill: incidence and outcome. J Crit Care 26, 593–599 (2011).

Valette, X. et al. Incidence, morbidity, and mortality of contrast-induced acute kidney injury in a surgical intensive care unit: a prospective cohort study. J Crit Care 27(322), e321-325 (2012).

Mansella, G. et al. Delayed Diagnosis in Pulmonary Embolism: Frequency, Patient Characteristics, and Outcome. Respiration 99, 589–597 (2020).

Beckett, K. R., Moriarity, A. K. & Langer, J. M. Safe Use of Contrast Media: What the Radiologist Needs to Know. Radiographics 35, 1738–1750 (2015).

Shaish, H. et al. Diagnostic Accuracy of Unenhanced Computed Tomography for Evaluation of Acute Abdominal Pain in the Emergency Department. JAMA Surg 158, e231112 (2023).

Feng, Y. et al. Characterization of Risk Prediction Models for Acute Kidney Injury: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open 6, e2313359 (2023).

Tomašev, N. et al. A clinically applicable approach to continuous prediction of future acute kidney injury. Nature 572, 116–119 (2019).

von Elm, E. et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet 370, 1453–1457 (2007).

Nijssen, E. C. et al. Prophylactic hydration to protect renal function from intravascular iodinated contrast material in patients at high risk of contrast-induced nephropathy (AMACING): a prospective, randomised, phase 3, controlled, open-label, non-inferiority trial. Lancet 389, 1312–1322 (2017).

Nohara, Y., Matsumoto, K., Soejima, H. & Nakashima, N. Explanation of machine learning models using shapley additive explanation and application for real data in hospital. Comput Methods Programs Biomed 214, 106584 (2022).

Rodríguez-Pérez, R. & Bajorath, J. Interpretation of machine learning models using shapley values: application to compound potency and multi-target activity predictions. J Comput Aided Mol Des 34, 1013–1026 (2020).

Xie, F., Chakraborty, B., Ong, M. E. H., Goldstein, B. A. & Liu, N. AutoScore: A Machine Learning-Based Automatic Clinical Score Generator and Its Application to Mortality Prediction Using Electronic Health Records. JMIR Med Inform 8, e21798 (2020).

Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Acute Kidney Injury Work Group. KDIGO Clinical Practice Guideline for Acute Kidney Injury. Kidney Int 2, 1–138 (Suppl. 2012).

Kellum, J. A. et al. Acute kidney injury. Nat Rev Dis Primers 7, 52 (2021).

Hinson, J. S. et al. Risk of Acute Kidney Injury Associated With Medication Administration in the Emergency Department. J Emerg Med 58, 487–496 (2020).

Ma, X., Mo, C., Li, Y., Chen, X. & Gui, C. Prediction of the development of contrast-induced nephropathy following percutaneous coronary artery intervention by machine learning. Acta Cardiol 78, 912–921 (2023).

Ibrahim, N. E. et al. A clinical, proteomics, and artificial intelligence-driven model to predict acute kidney injury in patients undergoing coronary angiography. Clin Cardiol 42, 292–298 (2019).

Sun, L. et al. Machine Learning to Predict Contrast-Induced Acute Kidney Injury in Patients With Acute Myocardial Infarction. Front Med (Lausanne) 7, 592007 (2020).

Huang, C. et al. Development and Validation of a Model for Predicting the Risk of Acute Kidney Injury Associated With Contrast Volume Levels During Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. JAMA Netw Open 2, e1916021 (2019).

Huang, C. et al. Enhancing the prediction of acute kidney injury risk after percutaneous coronary intervention using machine learning techniques: A retrospective cohort study. PLoS Med 15, e1002703 (2018).

Niimi, N. et al. Machine learning models for prediction of adverse events after percutaneous coronary intervention. Sci Rep 12, 6262 (2022).

Bansal, S. & Patel, R. N. Pathophysiology of Contrast-Induced Acute Kidney Injury. Interv Cardiol Clin 9, 293–298 (2020).

Workman, R. J. et al. Relationship of renal hemodynamic and functional changes following intravascular contrast to the renin-angiotensin system and renal prostacyclin in the dog. Invest Radiol 18, 160–166 (1983).

Messana, J. M., Cieslinski, D. A., Nguyen, V. D. & Humes, H. D. Comparison of the toxicity of the radiocontrast agents, iopamidol and diatrizoate, to rabbit renal proximal tubule cells in vitro. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 244, 1139–1144 (1988).

Liss, P., Nygren, A., Erikson, U. & Ulfendahl, H. R. Injection of low and iso-osmolar contrast medium decreases oxygen tension in the renal medulla. Kidney Int 53, 698–702 (1998).

Davenport, M. S. et al. Use of Intravenous Iodinated Contrast Media in Patients with Kidney Disease: Consensus Statements from the American College of Radiology and the National Kidney Foundation. Radiology 294, 660–668 (2020).

Lun, Z. et al. Hypertension as a Risk Factor for Contrast-Associated Acute Kidney Injury: A Meta-Analysis Including 2,830,338 Patients. Kidney Blood Press Res 46, 670–692 (2021).

Sendeski, M., Patzak, A. & Persson, P. B. Constriction of the vasa recta, the vessels supplying the area at risk for acute kidney injury, by four different iodinated contrast media, evaluating ionic, nonionic, monomeric and dimeric agents. Invest Radiol 45, 453–457 (2010).

Wiedermann, C. J., Wiedermann, W. & Joannidis, M. Causal relationship between hypoalbuminemia and acute kidney injury. World J Nephrol 6, 176–187 (2017).

Liu, L. et al. Predictive Value of Hypoalbuminemia for Contrast-Associated Acute Kidney Injury: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Angiology 72, 616–624 (2021).

Ostermann, M. et al. Controversies in acute kidney injury: conclusions from a Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Conference. Kidney Int 98, 294–309 (2020).

Wilhelm-Leen, E., Montez-Rath, M. E. & Chertow, G. Estimating the Risk of Radiocontrast-Associated Nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol 28, 653–659 (2017).

Aycock, R. D. et al. Acute Kidney Injury After Computed Tomography: A Meta-analysis. Ann Emerg Med 71, 44–53 e44 (2018).

Hassen, G. W. et al. Follow up for emergency department patients after intravenous contrast and risk of nephropathy. West J Emerg Med 15, 276–281 (2014).

Michel, P. et al. Meta-analysis of intravascular volume expansion strategies to prevent contrast-associated acute kidney injury following invasive angiography. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 98, 1120–1132 (2021).

Gameiro, J., Fonseca, J. A., Outerelo, C. & Lopes, J. A. Acute Kidney Injury: From Diagnosis to Prevention and Treatment Strategies. J Clin Med 9 (2020).

Acknowledgements

K. Lee was supported by grants from the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (HI19C1337), National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) (NRF-2021R1A6A3A03039863), Samsung Medical Center Grant (SMO1230251), and Young Investigator Research Grant from the Korean Nephrology Research Foundation (2023). J. Jeon was supported by an NRF grant funded by the Korean government (NRF-2022R1F1A1068198) and the Bio&Medical Technology Development Program of the NRF funded by the Korean government (MSIT) (RS-2023-00222838). H.R. Jang was supported by NRF grants (NRF-2022R1A2B5B01001298, NRF-2019R1A5A2027340, and HR22C1363) and a Korean Fund for Regenerative Medicine grant (Ministry of Science and ICT, Ministry of Health & Welfare, grant number 22A0302L1-01), which is funded by the Korean government.

Funding

No funding source involvement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H. R. Jang and W. C. Cha designed the study. K. Lee and W. Jung drafted the manuscript. W. Jung and W.C. Cha curated and analyzed the data. K. Lee, W. Jung, J. Jeon, H. Chang, H.R. Jang, and W.C. Cha interpreted the data. J. Jeon, H. Chang, J.E. Lee, W. Huh, W.C. Cha, and H.R. Jang revised the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, K., Jung, W., Jeon, J. et al. Prediction of contrast-associated acute kidney injury with machine-learning in patients undergoing contrast-enhanced computed tomography in emergency department. Sci Rep 15, 7088 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86933-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86933-9

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Research trends and ethical perspectives on explainable artificial intelligence in emergency medicine: a bibliometric analysis

Scandinavian Journal of Trauma, Resuscitation and Emergency Medicine (2026)