Abstract

Spirometry findings, such as restrictive spirometry and airflow obstruction, are associated with renal outcomes. Effects of spirometry findings such as preserved ratio impaired spirometry (PRISm) and its trajectories on renal outcomes are unclear. This study aimed to investigate the impact of baseline and trajectories of spirometry findings on future chronic kidney disease (CKD) events. This UK Biobank cohort study included participants with CKD who underwent spirometry at baseline (2006–2010). Lung function trajectories were determined using baseline and follow-up spirometry (2014–2020). Cox proportional hazards multivariate regression analysis was used to analyze the association between lung function and the incident CKD. In the baseline analysis (n = 282,354), fully adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) for PRISm participants (vs. normal spirometry) were 1.20 (1.07–1.34) for CKD and 1.51 (1.04–2.19) for end-stage renal disease (ESRD). Over an average 13.8-year follow-up period, 789 participants developed CKD. Trajectory analysis revealed higher CKD incidence with persistent AO (HR = 1.47(1.03–2.12)) and PRISm (HR = 1.28(0.88–1.88)) compared to normal lung function. Transitioning from AO to PRISm was associated with lower CKD incidence (HR = 0.27(0.08–0.93)). Recovery of normal lung function from AO could avert 16% of CKD cases. Our study indicated that baseline PRISm and airflow obstruction are associated with higher risk of incident CKD. Moreover, those with persistent AO findings had a higher risk of CKD incidence. These findings underscore the complex link between spirometry findings and renal outcomes and highlight the importance of considering respiratory and renal health in clinical assessments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Chronic kidney disease (CKD), affecting up to 13.4% of the global population1, is associated with pulmonary problems, such as sleep apnea and chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder (COPD). Respiratory complications, influenced by fluid imbalance and declining glomerular filtration rate2, advance as CKD progresses and contribute to systemic effects, including malnutrition, anemia, and cardiovascular diseases3,4. Recent evidence suggest that there is an association between impaired lung function and kidney function and outcomes3,5,6,7.

Preserved ratio impaired spirometry (PRISm), defined as a reduced forced expiratory volume (FEV₁) (< 80% of predicted value) and a FEV₁/FVC ratio of ≥ 0.70, affects 5–20% of adults globally8, with a higher incidence in smokers. While such individuals do not meet the criteria for COPD, they demonstrate increased respiratory symptoms9,10 and a higher risk of cardiovascular outcomes11,12, and all-cause mortality11,13,14. Several studies have linked airflow obstruction (pre-bronchodilator FEV₁/FVC ratio < 0.7), and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) to chronic kidney disease (CKD)3,5,7,15,16. However, information on the risk of kidney disease associated with PRISm (preserved ratio impaired spirometry) and lung function trajectories is still limited.

Given this uncertainty, we aimed to use data from the UK Biobank study to explore the associations between baseline spirometry findings (PRISm and AO) and the risk of chronic kidney disease (CKD) and end-stage renal disease (ESRD). We also analyzed the trajectories of these findings to assess the risk of CKD incidence at follow-up.

Methods

Study population

The UK Biobank is a nationwide cohort study comprising 502,394 participants aged 37–73 years, recruited between 2006 and 2010 across the United Kingdom. Detailed information on the UK Biobank study can be found in prior publications17. After providing written informed consent, the participants visited assessment centers where they completed touchscreen questionnaires and nurse interviews as part of the baseline survey covering various aspects, including sociodemographic factors, dietary habits, lifestyle, reproductive history, environmental factors, physical measurements, and biological sample collection.

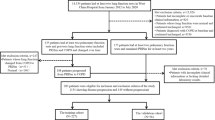

Participants who had functional or structural renal impairment or disease at baseline were excluded from the study. Those with missing data (including those with “prefer not to answer” response) regarding annual household income (AHI), education status, smoking status, alcohol drinking frequency and status, body mass index (BMI), were further excluded from the analysis (Fig. 1). Ethical approval for the UK Biobank study was obtained from the Northwest Multicenter Research Ethics Committee. All methods were performed following the relevant guidelines and regulations. This study was conducted using resources provided by the UK Biobank (application number 92858).

Spirometry assessment

During recruitment, spirometric assessments were conducted as part of the baseline evaluation. Participants were guided by trained personnel to use the spirometer (Pneumotrac 6800; Vitalograph). Each participant performed two to three forced expiratory maneuvers using a computer that automatically assessed the repeatability of the initial two blows. If these two blows exhibited an acceptable level of repeatability (defined as a < 5% difference in FVC and FEV₁), there was no need for a third one. Trained investigators carefully evaluated the spirometry results and selected the highest recorded FEV₁ and FVC values from the acceptable blows as the best-measured values used in this study. In-depth details of the breath spirometry procedure at the UK Biobank can be found at https://biobank.ndph.ox.ac.uk/ukb/ukb/docs/Spirometry.pdf.

The best spirometry measurements (FEV₁ and FVC) obtained were converted to % predicted values based on demographic data (age, height, sex, and ethnicity) using the Global Lung Function Initiative (GLI) 2012 equations. The lower limits of normal (LLN) for spirometry parameters were also calculated using the GLI-2012 equations. Participants were classified into three mutually exclusive groups using GLI-defined spirometry impairment: (i) airflow obstruction (AO), FEV₁/FVC < LLN; (ii) PRISm, FEV₁/FVC > LLN and FEV₁ < LLN; and (iii) normal spirometry without restrictive or obstructive impairment18. Restrictive PRISm was defined as FEV₁ < LLN, FVC < LLN, and FEV₁/FVC > LLN; non-restrictive PRISm was defined as FEV₁ < LLN, FVC > LLN, and FEV₁/FVC > LLN.

The participants were invited for a repeat survey using repeat spirometry. The follow-up analysis included only individuals who were enrolled at baseline. When multiple follow-up spirometry results were available, the latest follow-up best-measure spirometry was used. Individuals without data on AHI, smoking status, alcohol drinking frequency and status, or BMI at follow-up were excluded (Fig. 1).

Covariates and study outcomes

Potential confounders, including sociodemographic characteristics (age, sex, ethnicity, and household income) and lifestyle factors (smoking status and alcohol drinking frequency and status), were incorporated into this study using a baseline questionnaire. BMI (obtained by dividing weight in kilograms by the square of height in meters) and waist circumference were determined by physical examination. Hyperlipidemia and cardiovascular diseases were assessed through self-reporting. Cardiovascular conditions included heart failure, stroke, myocardial infarction, cardiomyopathy, peripheral vascular disease, deep venous thrombosis, arrhythmia, and heart or valve problems such as aortic stenosis, aortic regurgitation, and mitral regurgitation. Diabetes was determined based on self-reported history and use of insulin or antidiabetics. Hypertension was defined as a self-reported history of hypertension, use of antihypertensives, and systolic and diastolic blood pressure > 140 mmHg or > 90 mmHg, respectively. Details of these evaluations are available on the UK Biobank website (https://biobank.ndph.ox.ac.uk/ukb/search.cgi).

For baseline analysis, incident CKD and ESRD were identified as study outcomes. In the follow-up analysis, the outcome focused solely on CKD due to the absence of ESRD events in one or more trajectories. To identify CKD, we relied on “first occurrence” data, encompassing the date of the initial recording of a specific outcome and its information source. A 3-character International Classification of Diseases 10th Edition (ICD-10) code was generated by mapping primary care data, hospital inpatient data, death registries, and self-reported conditions obtained at baseline. Specifically, we used the ICD-10 code N18 to identify the participants with CKD. The identification of ESRD involved algorithmic combinations of coded information from the UK Biobank’s baseline assessment data collection, hospital admissions, and death registries. The outcomes were identified from the baseline (2006–2012) to the latest date (November 21, 2022). Participants were censored at the earliest date of death or the corresponding end of follow-up (November 21, 2022) if they did not record an event.

Statistical analysis

The lower limits of normal (LLN) and percent predicted values for FEV₁ and FVC were calculated using the GLI-2012 equations with the RSpiro package in R version 4.3.0 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing). To assess the nonlinear relationship between FEV₁% and FVC% predicted with the risk of CKD, we used a restricted cubic spline (RCS) model featuring three knots (10th, 50th, and 90th percentiles). Cumulative incidence was calculated using the tidycmprsk package.

Demographic differences between the lung function groups were evaluated by comparing participants with PRISm and AO to those with normal spirometry. Continuous outcomes were analyzed using the Mann–Whitney U test, while P-values for categorical variables were determined using Pearson’s chi-square test. Continuous and categorical variables are presented as means (with standard errors) and counts (with percentages), respectively.

At baseline, participants underwent their initial spirometry from 2006 to 2010, with follow-up spirometry conducted at subsequent assessment visits. Cox proportional hazards models were utilized to calculate hazard ratios (HRs) and their corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the incidence of outcomes (CKD or ESRD) in relation to baseline spirometry findings and their trajectories. Lung function trajectories were divided into nine categories: normal to normal (reference group), normal to PRISm, normal to AO, PRISm to PRISm, PRISm to AO, PRISm to normal, AO to AO, AO to PRISm, and AO to normal. The assumptions of the Cox proportional hazards model were tested using the cox.zph() function from the “survival” package. We employed three models: Model 1 adjusted for age, sex, ethnicity, AHI (< £31,000 or ≥ £31,000), and Education; Model 2 adjusted for BMI, waist circumference, smoking status (never, former, or current), alcohol drinking status (never, former, or current), and alcohol drinking frequency (< 3 times/week or ≥ 3 times/week); Model 3 adjusted for diabetes (self-report), hypertension (self-report), cardiovascular disease (self-report), and hyperlipidemia (self-report). For trajectory analysis, we reported results adjusted for variables collected during follow-up spirometry testing, as adjustment using baseline values yielded the same results. To provide additional insights into CKD risk among different lung function trajectories, we divided the samples into three groups as reference points: PRISm to PRISm, AO to AO, and normal to normal. We also excluded participants with self-reported interstitial lung diseases, including pulmonary fibrosis, sarcoidosis, pleural effusion, pleural plaques, and asbestosis, to analyze the robustness of our findings.

Estimates of the percentage of CKD events that could be prevented under four hypothetical scenarios were calculated using the “graphPAF” package. The equations are described elsewhere19. Each scenario was adjusted for the covariates used in Model 3. These scenarios are: 1. "Transition to PRISm": The participants transitioning from normal spirometry at baseline to PRISm at follow-up, 2. “Persistent PRISm” Participants maintaining PRISm throughout the follow-up period, 3. "Transition to AO": The participants transitioning from normal spirometry at baseline to AO at follow-up, 4. “Persistent AO”: The participants maintaining AO throughout the follow-up period.

All analyses were performed using R version 4.3.0, and statistical significance was set at a two-tailed P ≤ 0.05.

Results

Baseline characteristics

Among the 282,354 patients with the best FEV₁ and FVC measurements recruited from the UK Biobank, 25,181 (8.92%) were diagnosed with airways obstruction (AO) — 12,017 females and 13,164 males — while 24,581 (8.71%) had PRISm, comprising 12,518 females and 12,063 males. The baseline characteristics of the study participants are shown in Table 1. Participants with PRISm, compared to those with normal spirometry, were generally younger and had lower annual incomes. They were more likely to live in economically disadvantaged areas and showed higher levels of glycated hemoglobin, urine creatinine, and urine microalbumin. Additionally, individuals with PRISm had a higher prevalence of obesity and smoking. They also had a greater incidence of health conditions, including diabetes (7.94 vs. 3.58%), hypertension (31.21 vs. 23.35%), hyperlipidemia (22.5 vs. 15.94%), and cardiovascular disease (9.11 vs. 5.42%).

Baseline analysis

Table 2 shows the association between lung function and renal outcomes. PRISm was linked to an increased risk of developing CKD and ESRD across all analyzed models. After making full adjustments, the strength of the association showed a slight decrease but remained statistically significant. In Model 3, participants with PRISm had a significantly higher risk of incident CKD (HR 1.20, 95%CI 1.07–1.34) and ESRD (HR 1.51, 95% CI 1.04–2.19) compared to those with normal spirometry. Furthermore, after excluding participants with interstitial lung diseases, the results continued to be consistent (Supplementary Table 1). In the restricted cubic spline regression, the curves were reversed J shaped (P ˂0.05), indicating that individuals with lower FEV₁% predicted and FVC% predicted had a higher risk of CKD incidence (Fig. 2).

In comparison to individuals without restrictive PRISm at baseline, those with restrictive PRISm exhibited a significantly higher risk of developing chronic kidney disease (CKD) across all models (Table 3). The fully adjusted hazard ratio for incident CKD was 1.19 (95%CI, 1.05–1.35, P = 0.01) for participants with restrictive PRISm. Furthermore, individuals with baseline PRISm had a higher 5-year cumulative incidence of CKD (1.30%) compared to those with AO at 1.00% and individuals with normal lung function at 0.89% (Table 4).

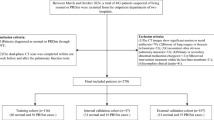

Trajectory analysis

Among the 35,478 patients with available follow-up spirometry data, 31,116 (87.7%) exhibited normal lung function, 1,877 (5.3%) were identified with PRISm, and 2,485 (7.0%) had AO at follow-up (Fig. 3). Over a median follow-up period of 13.8 years, 789 CKD cases were recorded.

Among those with baseline PRISm, 1,357 patients (60.4%) transitioned to normal spirometry, while 141 patients (6.3%) progressed to AO (Fig. 3). In contrast, among those with baseline AO, 1,170 patients (45.2%) transitioned to normal spirometry, and 276 patients (10.7%) progressed to PRISm. Individuals with PRISm findings transitioned to a different lung function group more frequently (66.7%) compared to those with normal spirometry findings (6.7%) or those with AO (55.9%).

Table 5 shows the association between lung function trajectories and the risk of incident CKD. In the fully adjusted model (Model 3), individuals with the AO-AO trajectory had a significantly higher risk of developing incident CKD compared to those with a normal-to-normal trajectory (HR: 1.47, 95%CI: 1.03–2.12). Although not statistically significant, the normal-PRISm trajectory (HR: 1.36, 95% CI: 0.95–1.95) and PRISm-PRISm trajectory (HR: 1.28, 95% CI: 0.88–1.88) also indicated an increased risk of CKD after full adjustment. In participants without interstitial lung diseases, similar results were observed. However, the association between the AO-AO trajectory and CKD risk was not present in this group (Supplementary Table 2). Cumulative incidence curves from the Cox models are displayed in Fig. 4.

Cumulative incidence curve for Cox models. Normal-Normal: Normal lung function at baseline and follow-up; Normal-PRISm: Normal lung function at baseline and PRISm at follow-up; Normal-AO: Normal lung function at baseline and airflow obstruction at follow-up; PRISm-Normal: PRISm at baseline and normal lung function at follow-up; PRISm-PRISm: PRISm at baseline and follow-up; PRISm-AO: PRISm at baseline and airflow obstruction at follow-up; AO-Normal: Airflow obstruction at baseline and normal lung function at follow-up; AO-PRISm: Airflow obstruction at baseline and PRISm at follow-up; AO-AO: Airflow obstruction at baseline and follow-up; CKD: Chronic CKD.

In comparison to participants with a persistent PRISm trajectory, those who transitioned to a normal trajectory had a lower risk of chronic kidney disease (CKD), although this difference was not statistically significant. Conversely, participants who moved from a persistent AO trajectory to PRISm experienced a significantly reduced risk of CKD after full adjustment (HR: 0.27, 95%CI: 0.08–0.93).

Among the four scenarios detailed in the "Methods" section, if participants who consistently exhibited PRISm) throughout the study had transitioned back to normal spirometry, it could have led to a 4.00% reduction in cases of CKD. Similarly, if participants who consistently displayed AO during the study had reverted to normal spirometry, a 16.30% decrease in CKD cases could have been achieved (Table 6).

Discussion

In this prospective cohort study utilizing data from the UK Biobank, we found that baseline PRISm and AO were linked to a higher risk of developing CKD and ESRD. Trajectory analysis revealed that persistent AO and PRISm were associated with an increased risk of developing CKD. However, after adjusting for comorbidities, the strength of the association diminished in persistent PRISm group. We also found that individuals transitioning from AO to PRISm had a lower risk of developing CKD compared to those with persistent AO-AO. Additionally, our analysis indicated a non-linear relationship between lung function indices (FEV₁% predicted and FVC%) and the risk of CKD, with a non-linear significance of P < 0.05. Therefore, this study serves as a pilot investigation into both baseline spirometry findings and their trajectories with the incidence of CKD.

Few studies have explored the relationship between lung function and renal outcomes. Notably, the ARIC study, spanning 25 years, reported a twofold increased risk of developing ESRD associated with restrictive spirometry patterns (FVC < 80% predicted with a normal FEV₁/FVC ratio) and a 1.5-fold increased risk for obstructive patterns compared to normal spirometry5. Similar associations were observed for the incidence of CKD. Consistent with these findings, we observed a higher risk of ESRD incidence among individuals with baseline AO (HR = 1.68) and PRISm (HR = 1.51). The ARIC study also identified that FVC%, particularly between < 85% and 95% predicted, was associated with an increased risk of ESRD incidence. In our study, we found a nonlinear relationship between predicted FVC% and the risk of developing CKD, with a higher risk associated with a lower FVC% predicted. A study using samples from China and Australia reported elevated adjusted odds ratios for reduced renal function in individuals with obstructive lung function7; the risk further increased when FEV₁ and FVC were both < 3.05 L. Kim et al.6 reported that a decreased FEV₁/FVC ratio was independently associated with a higher risk of developing CKD. In a 5-year follow-up of a Korean cohort, an FEV₁/FVC ratio < 0.8 was associated with a 35% increase in CKD incidence for a 10% decrease in the ratio20. Consistent with these findings, our study revealed that an FEV₁/FVC ratio < 0.7 (indicative of AO) was associated with a higher risk of CKD incidence (HR = 1.17). In contrast, Zaigham et al.21 concluded that low FEV₁ and FVC posed a risk for future CKD in men but not in women and that an FEV₁/FVC ratio < 0.7 did not increase the incidence of CKD in either men or women. PRISm may be a precursor to COPD, as indicated by the high transition rate from PRISm to AO reported in these studies13,14,22. Moreover, COPD is associated with an increased likelihood of developing CKD15,16,21,23,24,25. Despite a few discrepancies, our study and existing evidence emphasize the critical association between compromised lung function and the risk of CKD development.

PRISm is a prevalent condition that often transitions to other lung function abnormalities, such as AO, and may even return to normal spirometry26. Some studies have reported associations between restrictive spirometry and renal disease3,5,27. However, no reports are available on the impact of PRISm and AO trajectories on CKD incidence. To explore their effects on CKD development, we assessed the trajectories of PRISm and AO, in addition to baseline spirometry findings. By examining these trajectories, we found that persistent AO was associated with a higher risk of CKD incidence (HR = 1.47) compared with normal spirometry. Our study also showed that 16 out of 100 CKD cases could have been avoided if individuals had recovered to normal spirometry from AO. Although not statistically significant, transitioning to PRISm was associated with a higher risk of developing CKD (HR = 1.37), whereas recovery from PRISm was associated with a lower risk (HR = 0.86). Interestingly, baseline restrictive PRISm was associated with a significantly higher risk of CKD incidence than nonrestrictive PRISm (HR = 1.19). Overall, our findings suggest that maintaining normal lung function may help reduce the risk of CKD development.

The precise mechanism underlying the association between PRISm and CKD remains incompletely understood. However, several hypotheses have been proposed, drawing parallels with the known associations between obstructive lung function or COPD and CKD. Chronic hypoxia, a common feature of obstructive lung conditions, may contribute to renal damage through hypoxia, leading to a decline in renal function28. Chronic hypoxia has also been linked to atherosclerosis29, a recognized risk factor for CKD. Another potential mechanism involves the association between obstructive lung function and systemic inflammation, particularly through factors such as tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), interleukin 6 (IL-6), and C-reactive protein (CRP)30,31,32,33,34. This inflammation may contribute to the development of CKD through pathways involving vascular calcification and protein-energy wasting. A recent Mendelian Randomization study (a robust analytical tool for investigating causal relationships) indicated that a higher estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was causally linked to a higher FEV₁/FVC ratio and a reduced risk of obstructive lung diseases, including COPD and late-onset asthma35. Although these studies focused on obstructive lung diseases, similar mechanisms may also be involved in PRISm.

The UK Biobank study is one of the largest prospective cohorts globally, featuring extensive follow-up, comprehensive covariate measurements, and high-quality assessment of lung function. This enabled a robust exploration of spirometry patterns and their correlations with renal outcomes. However, the study had several limitations. The UK Biobank exclusively uses pre-bronchodilator spirometry, which, although commonly used, may lead to discrepancies in defining PRISm and obstructive patterns compared to post-bronchodilator spirometry36. It is important to note that we utilized the LLN criteria to define PRISm and AO to mitigate this issue. The study sample was limited to individuals of European and White ethnicity, excluding ethnic diversity, and the absence of younger participants may affect the generalizability of the findings. Additionally, follow-up participation was influenced by the proximity of participants to the assessment center, potentially introducing bias against those living further away or facing health-related challenges in attending follow-up visits. The UK Biobank is also subject to volunteer bias due to the lack of sample weights, which may impact the representativeness of the results. Medication use, particularly treatments such as steroids, could significantly influence both lung function and renal outcomes; however, medication data were not included in the current analysis, which represents another limitation of the study. Interestingly, nearly half of the AO participants in our study reverted to normal spirometry, which is unusual and may be attributable to factors such as diagnosis and treatment after the initial visit, natural fluctuations in lung function, improvements in spirometry technique, or changes in environmental exposures. Further research is warranted. Finally, as with any observational study, there is the possibility of collider bias, and despite comprehensive adjustments, residual confounding cannot be entirely ruled out. Addressing these limitations and expanding the research with larger samples, multiple spirometry assessments, and further classification of spirometry patterns could provide more nuanced insights into the complex associations between lung and renal health. Moreover, future research should focus on establishing the causal relationships between impaired lung function and renal outcomes.

In conclusion, several key findings emerged from this comprehensive lung function and renal outcomes analysis. Baseline PRISm and AO were associated with an elevated risk of CKD and ESRD compared to normal lung function, with PRISm showing a more pronounced effect. Persistent AO was linked to a higher risk of CKD, while transitioning from AO to PRISm was associated with a reduced risk. These results emphasize the complex relationship between spirometry patterns and renal outcomes, highlighting the importance of incorporating both respiratory and renal health into clinical assessments.

Data availability

“Data access to UK Biobank data is available to researchers via application. For instructions on gaining access, please visit https://www.ukbiobank.ac.uk/enable-your-research.”

Abbreviations

- AO:

-

Airflow obstruction

- CKD:

-

Chronic kidney disease

- COPD:

-

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder

- ESRD:

-

End-stage renal disease

- FEV₁:

-

Forced expiratory volume in 1 s

- FVC:

-

Forced vital capacity

- HR:

-

Hazard ratio

- PRISm:

-

Preserved ratio impaired spirometry

References

Hill, N. R. et al. Global prevalence of chronic kidney disease - a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 11(7), e0158765 (2016).

Prezant, D. J. Effect of uremia and its treatment on pulmonary function. Lung 168(1), 1–14 (1990).

Navaneethan, S. D. et al. Obstructive and restrictive lung function measures and CKD: national health and nutrition examination survey (NHANES) 2007–2012. Am J Kidney Diseases : Offic J Natl Kidney Foundation 68(3), 414–421 (2016).

Webster, A. C., Nagler, E. V., Morton, R. L. & Masson, P. Chronic kidney disease. Lancet (London, England) 389(10075), 1238–1252 (2017).

Sumida, K. et al. Lung function and incident kidney disease: the atherosclerosis risk in communities (ARIC) study. Am J Kidney Diseases: Offic J Natl Kidney Foundation 70(5), 675–685 (2017).

Kim, S. H., Kim, H. S., Min, H. K. & Lee, S. W. Obstructive spirometry pattern and the risk of chronic kidney disease: analysis from the community-based prospective Ansan-Ansung cohort in Korea. BMJ Open 11(3), e043432 (2021).

Yu, D., Chen, T., Cai, Y., Zhao, Z. & Simmons, D. Association between pulmonary function and renal function: findings from China and Australia. BMC Nephrol 18(1), 143 (2017).

Wan, E. S. The clinical spectrum of PRISm. Am J Resp Critical Care Med 206(5), 524–525 (2022).

Kalhan, R. et al. Respiratory symptoms in young adults and future lung disease. The CARDIA lung study. Am J Resp Critical Care Med 197(12), 1616–1624. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201710-2108OC (2018).

Guerra, S. et al. Morbidity and mortality associated with the restrictive spirometric pattern: a longitudinal study. Thorax 65(6), 499–504 (2010).

Wan, E. S. et al. Association between preserved ratio impaired spirometry and clinical outcomes in US adults. Jama 326(22), 2287–2298 (2021).

Zheng, J. et al. Preserved ratio impaired spirometry in relationship to cardiovascular outcomes: a large prospective cohort study. Chest 163(3), 610–623 (2023).

Wijnant, S. R. A. et al. Trajectory and mortality of preserved ratio impaired spirometry: the Rotterdam Study. Eur Resp J 55(1), 1901217. https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.01217-2019 (2020).

Marott, J. L., Ingebrigtsen, T. S., Çolak, Y., Vestbo, J. & Lange, P. Trajectory of preserved ratio impaired spirometry: natural history and long-term prognosis. Am J Resp Critical Care Med 204(8), 910–920 (2021).

Incalzi, R. A. et al. Chronic renal failure: a neglected comorbidity of COPD. Chest 137(4), 831–837 (2010).

Chen, C. Y. & Liao, K. M. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is associated with risk of chronic kidney disease: a nationwide case-cohort study. Sci Rep 6, 25855 (2016).

Wang, A., Tang, H., Zhang, N. & Feng, X. Association between novel glucose-lowering drugs and risk of asthma: a network meta-analysis of cardiorenal outcome trials. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 183, 109080 (2022).

Zhou, L. et al. Association of impaired lung function with dementia, and brain magnetic resonance imaging indices: a large population-based longitudinal study. Age Ageing https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afac269 (2022).

Bruzzi, P., Green, S. B., Byar, D. P., Brinton, L. A. & Schairer, C. Estimating the population attributable risk for multiple risk factors using case-control data. Am J Epidemiol 122(5), 904–914 (1985).

Kim, S. K. et al. Is decreased lung function associated with chronic kidney disease? A retrospective cohort study in Korea. BMJ Open 8(4), e018928 (2018).

Zaigham, S., Christensson, A., Wollmer, P. & Engström, G. Low lung function and the risk of incident chronic kidney disease in the Malmö Preventive Project cohort. BMC Nephrol 21(1), 124 (2020).

Wan, E. S. et al. Longitudinal phenotypes and mortality in preserved ratio impaired spirometry in the COPDGene study. Am J Resp Critical Care Med 198(11), 1397–1405 (2018).

Pelaia, C. et al. Predictors of renal function worsening in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): a multicenter observational study. Nutrients 13(8), 2811 (2021).

Elmahallawy, I. I. & Qora, M. A. Prevalence of chronic renal failure in COPD patients. Egypt J Chest Dis Tuberculosis 62(2), 221–227 (2013).

AbdelHalim, H. A. & AboElNaga, H. H. Is renal impairment an anticipated COPD comorbidity?. Resp Care 61(9), 1201–1206 (2016).

Higbee, D. H., Granell, R., Davey Smith, G. & Dodd, J. W. Prevalence, risk factors, and clinical implications of preserved ratio impaired spirometry: a UK Biobank cohort analysis. Lancet Resp Med 10(2), 149–157 (2022).

Mukai, H. et al. Restrictive lung disorder is common in patients with kidney failure and associates with protein-energy wasting, inflammation and cardiovascular disease. PloS ONE 13(4), e0195585 (2018).

Tanaka, S., Tanaka, T. & Nangaku, M. Hypoxia as a key player in the AKI-to-CKD transition. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 307(11), F1187–F1195 (2014).

Savransky, V. et al. Chronic intermittent hypoxia induces atherosclerosis. Am J Resp Critical Care Med 175(12), 1290–1297 (2007).

Carrero, J. J. & Stenvinkel, P. Persistent inflammation as a catalyst for other risk factors in chronic kidney disease: a hypothesis proposal. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol: CJASN 4(Suppl 1), S49-55 (2009).

Barnes, P. J. The cytokine network in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Resp Cell Mol Biol 41(6), 631–638 (2009).

Pinto-Plata, V. M. et al. C-reactive protein in patients with COPD, control smokers and non-smokers. Thorax 61(1), 23–28 (2006).

Gan, W. Q., Man, S. F., Senthilselvan, A. & Sin, D. D. Association between chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and systemic inflammation: a systematic review and a meta-analysis. Thorax 59(7), 574–580 (2004).

Gaddam, S., Gunukula, S. K., Lohr, J. W. & Arora, P. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pulmonary Med 16(1), 158 (2016).

Park, S. et al. Kidney function and obstructive lung disease: a bidirectional Mendelian randomisation study. Eur Resp J 58(6), 21008486 (2021).

Backman, H. et al. Restrictive spirometric pattern in the general adult population: methods of defining the condition and consequences on prevalence. Resp Med 120, 116–123 (2016).

Acknowledgements

This research has been conducted using the UK Biobank Resource under Application Number 92858.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number 82070851). The authors are solely responsible for the design and conduct of this study, all study analyses, drafting and editing of the manuscript, and final content.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

IP is the first author of this study. JBZ is the corresponding author. HJG, HX, YSQ, YHC, and JYZ revised the mansucript and take full responsibility as guarantors of the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. JBZ and IP contributed to the study design, data interpretation, and final manuscript approval.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

The UK Biobank’s study protocol was approved by the U.K. North West Multicenter Research Ethics Committee (reference no. 06/MRE8/65). This approval means that researchers do not require separate ethical clearance. UK Biobank obtained written informed consent from all study participants before the assessment center visit.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Patel, I., Zhang, J., Chai, Y. et al. Preserved ratio impaired spirometry, airflow obstruction, and their trajectories in relationship to chronic kidney disease: a prospective cohort study. Sci Rep 15, 3439 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86952-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86952-6