Abstract

This study presents a comprehensive numerical analysis of dynamic rupture and fault-induced seismic risks in deep roadway excavation environments, focusing on near-fault conditions. A quantitative assessment was conducted for faults within 5 m of the roadway, a critical range for evaluating heightened seismic risks. Our results demonstrate that within this proximity, fault slip and seismic moment increase significantly, with peak fault slip reaching 17.1 mm and seismic moment exceeding 3.9 × 1010 Nm. One of the key findings is the amplification effect of wave reflections along the exposed roadway surfaces, particularly in areas near the roof and sidewall. The peak particle velocity (PPV) on the roof reached 0.40 m/s, while the right sidewall recorded 0.49 m/s, highlighting elevated seismic impacts in these critical regions. The study also validated the linear slip weakening model, confirming its effectiveness in capturing the transition from static to dynamic friction during rupture and providing theoretical grounding for observed fault behavior. This research contributes novel insights into the fault-induced dynamic rupture process, particularly in ultra-close fault conditions, and emphasizes the need to account for fault proximity, frictional properties, and wave reflection in seismic hazard assessments. Our findings offer a foundation for improving seismic-resistant design in deep excavation operations, particularly in faulted geological settings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The safety of underground coal mining operations is critically influenced by the presence of fault structures1,2,3. When a fault slips, it can trigger a coal burst, which violently ejects fragmented coal and rock into the excavation space, posing severe risks to both equipment and workers4,5,6,7. Such events have been widely documented across various types of mining operations, including gold mining, tunneling, and especially coal mining8,9. As coal extraction moves into deeper and more geologically complex areas, the problem of rock or coal bursts has become increasingly acute, presenting significant challenges to maintaining safe and efficient mining operations10,11,12,13.

Field studies have consistently demonstrated the significant role that faults play in coal burst incidents. For example, in the Longfeng coal mine, 72% of the 50 recorded coal burst incidents were associated with faults, and 62% occurred in roadways that were close to fault zones14,15. This suggests that faults not only act as potential triggers for coal bursts but can also exacerbate the destructive effects under certain geological conditions16,17. Furthermore, rock bursts in the Jinping II Hydropower Station tunnels in China were often found to occur in areas characterized by geological faults or large joints18,19,20. In a 3-D environment, it has been observed that in South African gold mines, when the angle between the mining direction and the strike of a major fault is less than 20°, mining conditions can worsen significantly, often leading to dynamic fault slip events21. This risk is especially pronounced in reverse fault settings where panel rotation is considered; when the panel is parallel to the fault strike, the slip zone becomes most significant, resulting in the largest fault seismic moment22.

Coal bursts induced by fault slip typically involve a sudden release of accumulated energy, leading to the destabilization of the surrounding rock mass23,24,25,26. The stress concentrations caused by mining activities can trigger fault slips, releasing large amounts of strain energy and causing significant damage to the coal and rock mass27,28,29,30. Coal bursts not only disrupt mining operations but also pose serious threats to life31. For instance, a fault slip-induced coal burst in the Qianqiu coal mine resulted in 10 fatalities and trapped 75 individuals underground32. Similarly, in 2014, a coal burst at the Austar Coal Mine in Australia tragically resulted in the loss of two lives33. Consequently, the accurate prediction and effective prevention of coal bursts caused by fault slips have become critical areas of research in coal mining.

While theoretical analyses and laboratory experiments have provided valuable insights into the mechanisms of fault rupture and rupture-induced coal bursts, these approaches often face limitations when applied to complex geological settings34,35,36. Traditional experimental methods, especially in deep and high-stress environments, struggle to accurately replicate the dynamic processes of fault slip and their impact on coal seam stability37,38. As a result, numerical simulation has emerged as a more effective tool, capable of systematically modeling the intricate interactions between fault slip and rock bursts33,39,40,41. Sainoki and Mitri42,43,44,45 employed a series of static and dynamic numerical models to deeply explore fault slip behaviors resulting from stratified mining and to assess the impact of different geological conditions on mining induced fault slip.

In a related study, Vardar et al.39 investigated the impact of fault slip on coal burst susceptibility during underground roadway excavation. Using a 2-D numerical model developed in UDEC, they conducted a parametric analysis based on the geological and geotechnical conditions of Australian underground coal mines. Their work emphasized the effects of fault dip angle and mining depth on energy release characteristics, showing that faults located near roadways significantly increase total radiated seismic energy and peak kinetic energy. However, Vardar et al.39 primarily focused on the elastic strain energy release associated with fault proximity, which may not fully account for the complex dynamics of unstable energy release or fault instability. This limitation is particularly important, as the main triggers for coal bursts and rockbursts are often the sudden, non-stable release of elastic energy or the unstable failure of faults, typically modeled in elastic bodies46,47.

Building on the work of Vardar et al.39, this study extends the analysis by providing a more detailed investigation into dynamic rupture processes and fault instability, focusing on the unstable release of energy during roadway excavation. Our approach goes beyond static stability considerations to incorporate dynamic fault slip mechanisms and seismic wave amplification effects, specifically near the excavation boundary. We also validated the linear slip weakening law, which allowed us to explore the temporal and spatial evolution of fault rupture. By evaluating the effects of fault proximity, critical slip distance, and dynamic friction, this study advances the understanding of fault-induced seismic hazards in deep mining environments. Our findings offer practical guidance for geotechnical engineers in mitigating seismic risks and improving the design of roadway structures in faulted geological conditions.

Numerical modeling approach

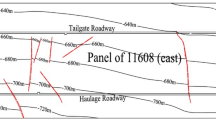

Engineering background

This study is conducted within the challenging geological conditions of underground coal mining in Queensland, Australia. The deep coal seams in this region are intersected by a network of geological faults, which present significant challenges for maintaining roadway stability, especially with respect to the risk of coal bursts. Coal bursts, characterized by a sudden release of energy, can lead to the violent ejection of coal and rock, posing serious risks to mining operations21.

The coal seam under investigation is 5 m thick, with the roadway positioned 0.3 m above the seam floor, leaving 1.1 m of coal in the immediate roof. This geological setup is typical for the area. Above the coal seam lies a 5 m thick siltstone unit, further capped by competent sandstone layers, while the floor beneath the seam consists of strong sandstone. These geological features contribute to the overall stability of the excavation (Table 1).

A major concern in this mining environment is the presence of geological faults, which significantly influence roadway stability. The faults in this region vary in proximity to the roadway and exhibit different dip angles, both critical factors affecting the stress distribution around the excavation39. This modeling approach simulates the realistic conditions found in the mine, helping to understand how fault geometry influences seismic risk. The stress conditions modeled reflect the typical in situ stress regime around normal faults in Queensland. Specifically, rather than using constant values, we account for the specific characteristics of the normal fault setting by assuming that the vertical stress is due to the overburden weight39. To ensure consistency with previous analyses, particularly those focused on strain energy density (SED), this study initially fixes the fault dip angle at 75°, the same angle used in Vardar et al.39. The minimum horizontal stress set at 0.5 times of the vertical stress in the x-direction.

Model setup: governing equations, assumptions, and input parameters

We employed a 2-D plane-strain model using a thin rectangular domain, as illustrated in Fig. 1. The computational domain extended 120 m along the x-axis (mining direction) and 100 m in the vertical y-axis, with a fixed width of 1 m along the z-axis. The origin was positioned at the lower-left corner of the model, with the positive y-direction defined upwards. The depth h was calculated as h = 500-z, representing the vertical distance from the surface (Table 1).

Schematic representation of the numerical model setup and geological conditions. (a) Model setup showing 75° fault dip, roadway dimensions, and rock strata for simulating fault slip. (b) Local coordinate system established on the roadway and fault. (c) Stratigraphic profile based on the fault geometry in (a).

The governing equation for dynamic modeling is the equation of motion shown as follows.

where σij, j represents the spatial derivative of stress tensor, where compressive stress is considered positive. Here, i and j are indices referring to the spatial directions x, and y. Specifically, i indicates the direction of the stress component (e.g., σxx, σxy, etc.), and j refers to the direction along which the derivative is taken (i.e., the derivative with respect to x, or y) and fi is the body force field per unit volume. The term ui denotes the displacement vector field in the i-th direction.

The displacement boundary conditions are as follows:

Specifically,\(\:\left\{\begin{array}{c}{disp}_{x}=0;\:for\:x=\:0\:m,\\\:{disp}_{y}=0;\:for\:y=\:0\:m,\\\:{disp}_{z}=0;\:for\:z=\:0\:m\:and\:1\:m\end{array}\right.\)

where dispi denotes the displacement in the i-th direction, with i corresponding to x, y, or z.

To define the stress conditions in the static modeling, we introduce the background stress σi where i is either h, or v. σv (x, y), which is self-gravity and represents the stress condition along the y-axis (Table 2).

where the depth h is given by h = 500-y in meters.

Horizontal stress (σh) results from tectonic forces or lateral constraints exerted by surrounding rock. The ratio of horizontal stress to vertical stress, denoted as r, provides insight into the relative magnitude of these two stress components:

Assess fault stability

σ n and τ on an inclined fault plane

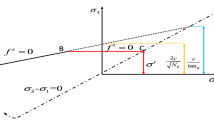

When the fault plane is inclined at an angle φ, σv and σh decompose into normal stress (σn) and shear stress (τ) acting on the fault plane. σn is the compressive force perpendicular to the fault plane, acting to stabilize the fault by preventing slip. τ is the force parallel to the fault plane, which drives fault slip (Fig. 2a). The σn and τ on a fault plane inclined at angle φ can be calculated as:

Equation 5 shows how stress varies depending on the φ and the relative magnitudes of σv and σh. As φ increases, the normal and shear stresses change, influencing the likelihood of fault slip.

Definition of K

K is a key parameter used to assess fault stability, defined as the ratio of τ to σn on the fault plane:

For the background stress effect, we further introduce K0

A higher K0 value indicates greater shear stress relative to normal stress, making the fault more prone to slip. Understanding how K0 varies with r and φ is essential for evaluating fault stability and seismic risk in roadway excavation operations.

Evaluation of K 0 in normal faulting conditions

In Fig. 3a, the x-axis represents the fault dip angle φ, ranging from 0° to 90°, while the y-axis shows K0. Each curve corresponds to a different r (0.5, 0.6, 0.7, and 0.8). As φ increases from 0° to 30°, K0 rises nonlinearly across all values of r, indicating that the steeper the fault, the greater the shear stress relative to the normal stress. For r = 0.5, K0 reaches a maximum value of 0.35 at φ = 35°; for r = 0.6, the maximum value of 0.26 occurs at φ = 38°; for r = 0.7, the peak of 0.18 is found at φ = 40°; and for r = 0.8, K0 peaks at 0.11 around φ = 42°. As the dip angle continues to increase beyond these points, K0 decreases steadily, eventually dropping to 0 at φ = 90°. For a detailed analysis of the changes in normal and shear stresses on the fault, refer to Fig. S1, which shows the variation of K0 as a function of φ under different r with an assumed σv of 1.0. This emphasizes the critical role tectonic stress conditions play in determining fault slip potential.

Figure 3b explores the relationship between K0 and r, with curves for various dip angles φ (40°, 50°, 60°, 70°, 80°, and 75° for the current study). The x-axis represents r, while the y-axis again shows K0. As r increases, K0 decreases nonlinearly across all dip angles, with the trend being more pronounced for shallower angles. For steeper fault dip angles, such as 75° in this study, K0 starts at approximately 0.27 when r is small and progressively decreases to zero as r increases. This indicates that, in steeply dipping faults, the effect of increasing horizontal stress ratio significantly reduces shear stress relative to normal stress.

These results demonstrate the substantial variability in fault stability across different dip angles and horizontal stress ratios, underscoring the importance of targeted monitoring in roadway excavation operations. For instance, in the current study, when the fault dip angle is 75°, K0 increases as r decreases, highlighting the need for careful consideration of fault geometry when assessing seismic risk.

Mohr-Coulomb criterion and slip weakening law

In the previous section, we analyzed the stress state around the roadway excavation through the parameters K and K0, which describe the ratio of horizontal to vertical stress and their impact on fault stability. In this section, we extend our analysis by incorporating the Mohr-Coulomb failure criterion and the slip weakening law to further model the fault behavior during and after roadway excavation-induced stress redistribution.

The Mohr-Coulomb failure criterion serves as the basis for determining when fault slip will initiate due to the altered stress field caused by roadway excavation. This criterion is represented by:

where µs denote the static friction coefficient, and C represents cohesion, which is set to 0 in this study.

In our model, we examine how the excavation of the roadway modifies the local stress state, particularly focusing on the evolution of K values around critical fault zones. This enables us to predict how the fault behaves as the excavation progresses, especially when the shear stress approaches or exceeds the critical threshold defined by the Mohr-Coulomb criterion.

Once fault slip is initiated due to the stress concentration around the roadway, we utilize the linear slip weakening law (LSW) to model the dynamic behavior of the fault during rupture. This law describes how the shear strength of the fault decreases as slip displacement accumulates, a process that is crucial for simulating the fault’s response to excavation-induced stress changes. LSW is expressed as:

where µd denote the dynamic friction coefficient, Dc is the critical slip distance, d is the slip (Table 1; Fig. 2b). Dc is assumed between 1.0 mm, 1.5 mm and 2.0 mm, which falls within the range of values typically selected in numerical simulations48,49,50.

This formulation allows us to track the evolution of fault slip and weakening processes that occur due to the excavation of the roadway. As the roadway excavation alters the local stress distribution, we focus on the interplay between stress concentration and fault slip dynamics. LSW is essential in our analysis to capture how the fault progressively weakens as slip progresses, which is critical for understanding potential seismic events triggered by roadway excavation.

PyLith: static and dynamic analysis

In this section, we present the numerical settings and methodologies employed in our study, which begins by replicating the results of Vardar et al.39 as a foundational step. By accurately reproducing their findings, we aim to validate the reliability of our model before extending it to dynamic simulations using PyLith 4.0.051,52. This approach allows us to ensure that our 2-D model builds upon a verified baseline, thereby enhancing its credibility when applied to the complex scenarios typical of deep roadway excavation environments.

The model domain was set to 120 m×100 m×1 m, with absorbing boundary conditions applied on all sides except the free surface to minimize reflections and accurately simulate dynamic rupture processes. The model was discretized using a fine mesh of tetrahedral elements, with a resolution of 0.05 m near the rupture zone, gradually increasing by a factor of 1.02 towards the boundaries. This configuration resulted in a highly detailed mesh of 9,681,458 to 9,681,582 elements (Table. S1), ensuring the accuracy of the simulation across different scales.

Static simulation conditions and methodology

Before delving into dynamic simulations, it was essential to establish a reliable static baseline. In situ stress conditions were applied to the model to replicate the actual stress environment in a roadway excavation setting. An initial equilibrium state was reached through iterative solutions, ensuring that the model accurately reflected the stress distributions present before excavation.

The excavation process was then simulated by sequentially removing elements of the roadway and gradually reducing the internal boundary forces surrounding the excavation site. This staged approach was critical in minimizing the potential dynamic effects associated with an instantaneous excavation, thereby providing a realistic representation of progressive roadway excavation operations. The static solution derived from these simulations served as a foundation for subsequent dynamic analyses by ensuring that the stress distribution before dynamic rupture accurately reflects realistic conditions, integrating both in situ stress and mining-induced perturbations.

Dynamic simulation conditions and methodology

With the static equilibrium established, we proceeded to simulate the dynamic rupture processes. The dynamic simulations were initiated using the stress state distribution obtained from the static analysis, which combined mining-induced stress perturbations with the background stress field. During the nucleation phase of dynamic rupture, classical nucleation theory53 was applied in conjunction with the LSW model to define the fault boundary conditions. This approach ensured that the critical nucleation size, as described in Li et al.7, and the transition from static to dynamic rupture were accurately represented. While our current model simplifies the time-dependent nature of the nucleation process to a static solution for computational clarity, this limitation has been explicitly acknowledged, along with ongoing efforts to refine its characterization under realistic mining conditions.

To achieve accurate spatial and temporal resolution near the rupture tips, the average diameter of the elements (Δx) is set at 0.05 m. Following the numerical stability conditions (Eq. 10)48,54, Δx is taken as smaller than the one thirds of the static cohesive zone length (\(\:{\varLambda\:}_{0}\)) as shown in Fig. 4a:

The initial time step was set at 10− 5 s, complying with the Courant-Friedrichs-Lewy (CFL) condition, to ensure CFL < 0.71, as shown in Eq. 1155. The time step in our current models, as shown in Fig. 4b, also satisfies the stability condition.

This approach allowed for a precise resolution of the rapid evolution of stress and displacement fields, capturing the full temporal dynamics of the rupture process from initiation to termination. The primary objective of these numerical simulations is to thoroughly investigate how varying fault conditions and proximity to roadways influence both static stability and dynamic rupture processes in roadway excavation environments. By adjusting key parameters such as the critical slip weakening distance (Dc), dynamic friction coefficient (µd), and fault-roadway distance (D), we aim to identify critical thresholds that could lead to increased seismic risks. The insights gained from these simulations are expected to enhance our understanding of fault-induced dynamic ruptures and provide practical guidelines for improving safety protocols in roadway excavation operations. This detailed numerical setup ensures that our models are both robust and precise, enabling a comprehensive analysis of the factors that influence fault stability and seismic activity in complex geological settings.

Strain energy density (SED) and seismic moment

This study, based on the assumption of linear elasticity, employs the inverse form of Hooke’s law, where strain is expressed as a function of stress:

where, εij is the strain tensor components; σkl is the stress tensor components. Kijkl is the compliance tensor.

Based on Eq. 12, the strain energy density (ESED) can be derived as shown in the following Eq.

The trace operator refers to the sum of the diagonal components, while the determinant is defined in the standard manner56,57.

The excavation process leads to stress redistribution around the fault, which in turn induces fault slip. Using our model, we captured the coseismic slip of the fault and analyzed its implications for roadway excavation induced seismic activity. Subsequently, we computed the seismic moment (M0) resulting from the coseismic fault slip. The seismic moment quantitatively describes the energy released during fault slip and is given by the equation58,59,60,61:

where: M0 is the seismic moment, G is the shear modulus (Table 2), A is the fault slip area, \(\:\stackrel{-}{S}\) is the average slip. Ls and Lw represent the coseismic slip length and width, respectively. In this study, we assumed that Ls and Lw adhere to the empirical relationship Ls = 2Lw for moderate earthquakes, as proposed by Geller62.

By applying this formula, we quantitatively established a direct link between the coseismic fault slip and induced seismicity, enabling us to further assess the impact of fault slip on roadway stability and the associated seismic hazards.

Simulation results and discussion

Validation of model integrity through reproduction of Vardar et al.39

The first step of this study involved replicating the 2-D numerical model developed by Vardar et al.39 to ensure the reliability of our modeling framework, particularly regarding mesh configuration and computational outputs. This replication is crucial for validating the accuracy of our setup and ensuring consistency with the published data. Vardar et al.39 employed the Universal Distinct Element Code (UDEC), a numerical modeling software widely used for simulating jointed and blocky rock masses, to investigate the effect of fault proximity on coal burst proneness during roadway excavation. In our replication, we maintained the same geological and geotechnical conditions, including coal seam geometry, rock unit properties, and fault characteristics. Specifically, we ensured that fault dip angles, mining depths, and proximity values were consistent with those used in their original study.

Our replication aligns with the findings of Vardar et al.39 in terms of the distribution of SED around the fault and roadway. As shown in Fig. 5f, under µs = 10, no fault slip occurred, and the SED distribution around the roadway was symmetrical, consistent with the patterns observed in Fig. 4a39. The SED magnitudes in our model, ranging between 0 and 200 kJ/m3, closely match the results obtained by Vardar et al.39, demonstrating a strong consistency in energy release magnitudes.

Notably, we treated the surrounding rock mass as an elastic body, reflecting the elastic behavior of hard rock prone to rockbursts, and removed the plastic zone around the roadway within a 6 m radius39. This adjustment facilitates more accurate quantitative analysis of induced fault rupture and seismic wave interactions with the roadway. If we consider the plastic zone at a depth of 500 m, we would need to account for this 6 m plastic zone in future analyses.

Figure 5 illustrates the spatial distribution of SED in our model under varying proximity values (D = 1 m to D = 5 m) with a fixed fault dip angle of 75° and µs = 0.27. In our simulations, the concentration of SED within the coal seam increased as the fault approached the roadway, confirming that the stress accumulation patterns in our replication are consistent with Vardar et al.39 in Fig. 4. Given the nature of rockbursts, treating the rock mass as approximately elastic is expected to further strengthen the interaction between fault slip (both static and dynamic rupture) and the roadway as boundary conditions evolve.

We also observed that as the roadway approached the fault, the SED near the ribs increased, further supporting the need for quantitative analysis of the dynamic rupture and seismic wave impacts on the roadway when it is located near the fault. This interaction is essential for assessing the coal burst risk in faulted geological environments.

Fault static slip induced by roadway excavation

Roadway excavation-induced fault coseismic slip under varying friction parameters

To further understand the dynamics of fault slip induced by roadway excavation, we conducted an analysis of coseismic slip distributions under various fault conditions, as depicted in Fig. 6. The analysis explores the impact of different µs, Dc, and fault frictional behavior by comparing results with the Mohr-Coulomb criterion.

Figure 6a demonstrates the coseismic slip distributions for three different µs (0.27, 0.37, and 0.47) at D = 1 m, r = 0.5, and φ = 75°. As expected, the coseismic slip magnitudes decrease with increasing µs. When µs = 0.27, the largest coseismic slip, reaching approximately 17.1 mm at Fd = 2 m. In contrast, when µs increases to 0.47, the coseismic slip reduces to around 9.3 mm at Fd = 1 m. This inverse relationship between static friction and coseismic slip highlights the stabilizing effect of higher static friction on fault behavior, reducing the likelihood of coseismic events. In Fig. 6b, we further investigate the influence of Dc on coseismic slip, while maintaining static and dynamic friction coefficients of µs = 0.47 and µd = 0.27, respectively. The critical slip distances tested were Dc = 1 mm, 2 mm, and 3 mm. The results indicate that larger Dc values correspond to smaller coseismic slip. For example, with Dc = 3 mm, the coseismic slip reaches approximately 15.8 mm, whereas for Dc = 1 mm, it reaches around 16.5 mm. The findings reveal that both static friction and critical slip distance are pivotal in determining the magnitude and spatial distribution of coseismic slip along the fault plane.

Roadway excavation-induced fault coseismic slip and M 0 under different D

To further assess the response of faults during excavation-induced seismic events, we analyzed the distribution of coseismic slip and M0 under varying D and µs, as shown in Fig. 7. This analysis aims to elucidate the relationship between fault slip behavior and seismic energy release, which is crucial for understanding fault mechanisms during roadway excavation.

Figure 7a illustrates the variation of coseismic slip with D for a static friction coefficient of µs = 0.27, with r = 0.5 and φ = 75°. The results indicate a marked increase in coseismic slip as D decreases. When D is greater than 5 m, the slip remains below 5 mm; however, as D approaches 1 m, the coseismic slip increases significantly, reaching up to approximately 17.1 mm. This behavior suggests that as the fault moves closer to the roadway, stress concentration near the fault intensifies, leading to greater fault displacement during seismic events. Fig. S2 provides additional insights into τ, σn, K, and slip distributions under varying D for µs = 0.27, offering a more detailed understanding of fault instability.

Similarly, Fig. 7b shows the coseismic slip distribution for µs = 0.37 under the same geometric conditions. The slip behavior follows a similar pattern, with increasing displacement as D decreases. However, the magnitude of slip for µs = 0.37 is notably lower than that for µs = 0.27, further emphasizing that lower static friction coefficients result in more pronounced fault slip due to reduced resistance along the fault plane. For instance, at D = 1 m, the coseismic slip for µs = 0.37 exceeds 12 mm, whereas for µs = 0.27, it reaches approximately 17 mm. Fig. S3 provides the corresponding τ, σn, K, and slip distributions for µs = 0.37, reinforcing the observations about fault stability under varying frictional conditions. Fig. S4 presents the corresponding stress drop distribution (top) and fault slip (bottom) for µs = 0.37 and µs = 0.47 under D = 1 m.

Figure 7c explores the variation of M0 with D for both static friction coefficients, µs = 0.27 and µs = 0.37, integrating the results from Fig. 7a and b in conjunction with Eq. 14, Eq. 15, and the classic relationship from Geller62. The seismic moment, which quantifies the total energy released during fault slip, increases as the fault approaches the roadway. For both µs values, M0 reaches its maximum when D is approximately 1 m, with M0 approaching 39 × 109 Nm for µs = 0.27 and 4 × 109 Nm for µs = 0.37. This trend underscores the significant influence of D on seismic energy release, with faults in close proximity to the roadway exhibiting higher M0 values. Additionally, the higher M0 observed for µs = 0.27 suggests that lower static friction coefficients lead to more intense seismic activity, as reduced resistance on the fault plane allows for greater energy release during slip events.

These findings indicate that static friction coefficients and fault proximity are key factors in determining the magnitude of fault slip and the amount of seismic energy released during seismic events. As the fault approaches the roadway, lower friction coefficients result in more significant coseismic slip and higher seismic moments, increasing the potential for dynamic fault rupture and associated seismic hazards. Therefore, it is crucial to consider fault proximity and frictional properties when evaluating seismic risk in underground roadway excavation.

Validation of theoretical and numerical solutions

We conducted a K0-based analysis by selecting K values from areas unaffected by roadway excavation, representing the background stress state, and compared the theoretical and numerical solutions under a constant r = 0.5, as shown in Fig. 8. This analysis aims to evaluate the accuracy and consistency of the numerical model in capturing key stress responses within the fault system and to compare these results with established theoretical frameworks.

Figure 8 illustrates the relationship between K0 and φ under the condition of r = 0.5. Both the theoretical and numerical solutions exhibit a similar trend, with K0 increasing as φ rises up to 35°. Beyond φ = 35°, both solutions show a decline in K0. Notably, at φ = 65°, the numerical solution begins to diverge from the theoretical one, with the predicted K0 values from the numerical model approximately 10–12% lower than the theoretical estimates. This discrepancy may be attributed to the potential influence of stress redistribution in areas still affected by roadway excavation, which could alter the local stress field. Overall, the K0-based analysis demonstrates that while the theoretical model provides a solid foundation for understanding fault behavior, the numerical model closely aligns with theoretical predictions for the most part, maintaining relative stability in K0 values. The observed deviations at higher φ, however, underscore the importance of considering excavation-induced stress redistribution in such analyses.

Fault dynamic rupture induced by roadway excavation

By accurately utilizing the stress disturbances caused by the near-source effects of excavation, and applying the methods outlined in Sect. 2.3 and 2.4, we quantitatively evaluate the dynamic rupture behavior. Additionally, the study examines the fault’s dynamic response and the subsequent propagation of seismic waves, assessing their impact on roadway stability.

Dynamic rupture propagation

As illustrated in Fig. 9, the particle velocity distribution in the surrounding rock clearly demonstrates the seismic waves generated by dynamic rupture propagation, from t = 0 ms to t = 23 ms. The simulation conditions are set at D = 3 m, µs = 0.47, µd = 0.27, and Dc = 0.001 m. The figure highlights the localized area between the roadway and the fault, capturing both the dynamic slip and the propagation of seismic waves over time.

Dynamic rupture is markedly different from static stress redistribution. During the dynamic rupture process, fault slip accelerates rapidly and propagates through the surrounding rock mass at high velocities. The particle velocity distribution reflects the intensity and speed of the dynamic response, with the highest values concentrated near the fault and on the side closest to the roadway. This distribution further confirms that dynamic rupture induces significant stress perturbations within the roadway-fault system, with clearly visible wavefronts radiating from the fault. This demonstrates the critical role of seismic waves in the dynamic rupture phase, a factor absent in the static process.

The proximity between the fault and the roadway has a particularly strong influence on the rupture dynamics, with seismic waves focusing between the fault and the excavation site, leading to localized stress amplification and accelerated slip. The dynamic rupture and rapid seismic wave propagation depicted in Fig. 9 underscore the significant shift in fault mechanics from the static to the dynamic phase. The particle velocity distribution provides clear evidence of the intensity and localized impact of dynamic rupture, highlighting the importance of considering dynamic processes when assessing fault stability and seismic risk during roadway excavation.

Our focus is on the fault, analyzing the evolution of slip and slip rate over time, with a temporal resolution of 10− 5 s. We output data every 10− 3 s (1 ms). Figure 10 provides a detailed representation of the slip and slip rate distribution during dynamic rupture under the conditions of D = 3 m, µs = 0.47, µd = 0.27, and Dc = 0.001 m.

Figure 10a illustrates the slip evolution from t = 1 ms to t = 39 ms, with color transitions from red (at 1 ms) to purple (at 39 ms). This distribution clearly shows the progression of slip along the fault plane, with values steadily increasing as rupture propagates. By 39 ms, the cumulative slip reaches approximately 5.7 mm, indicating significant slip resulting from dynamic rupture. The figure also identifies the point of rupture initiation, showing that the slip process begins at the nucleation zone and gradually spreads outward along the fault.

Figuew 10b presents the slip rate distribution, emphasizing both the nucleation zone and the maximum slip rate (Rsmax ≈ 2.4 m/s). Similar to Fig. 10a, the same color transitions and time intervals are used to demonstrate the evolution of slip rate over time. The maximum slip rate occurs near the nucleation zone, aligning with the rupture initiation point. As rupture propagates, the slip rate gradually decreases, reflecting the natural attenuation of rupture speed as seismic energy dissipates. The peak slip rate of 2.4 m/s highlights the rapid response during the initial rupture phase, with the highest velocity concentrated near the starting point of rupture. This distribution provides critical insights into the dynamic stress release during fault rupture, clearly differentiating the high-speed dynamic phase from the previously discussed static behavior.

The steady increase in slip, combined with the rapid, concentrated slip rate in the nucleation zone, emphasizes the complex interaction between fault properties and seismic energy release. The maximum slip and slip rate indicate a highly dynamic process, with energy gradually dissipating as the rupture propagates away from the nucleation zone. This analysis further enhances our understanding of dynamic rupture mechanisms, complementing the particle velocity distribution shown in Fig. 9. For additional analysis on Dc = 1.5 mm and Dc = 2.0 mm, refer to Figs. S5 and S6. Notably, at Dc = 2.0 mm, under the given r and D conditions, almost no dynamic rupture occurs. This observation underscores the sensitivity of Dc and the complexity involved in dynamic rupture analysis. A summary of the key parameters observed during dynamic rupture is provided in Table 3.

Slip and slip rate distribution during dynamic rupture under conditions of D = 3 m, µs = 0.47, µd = 0.27, and Dc = 0.001 m. (a) Slip evolution over time from 1 ms to 39 ms, with uniform 1 ms intervals and color transition from red (1 ms, start) to purple (39 ms, end). (b) Slip rate distribution, highlighting the nucleation zone and maximum slip rate (Rsmax≈2.4 m/s), with the same color transition and time intervals.

Verifying LSW during dynamic rupture

Our goal is to validate the LSW under dynamic rupture conditions. During seismic events, as dynamic rupture propagates along the fault, different locations experience slip weakening at various times. In this process, stress transitions from static strength to dynamic strength, while the slip rate accelerates from zero to its maximum, with the slip distance traversing Dc, as theoretically defined. To thoroughly assess the accuracy of the LSW model, we selected 3 positions — Fd = 0 m, 5 m, and 10 m — and tracked the evolution of slip and slip rate at each point as the rupture progressed.

Using the data from Fig. 11 and Fig. S7, we conducted a comprehensive analysis of the temporal evolution of slip and slip rate during dynamic rupture. Slip weakening is characterized by a transition in stress from static to dynamic strength, with the slip rate rapidly increasing to a peak before gradually declining as the slip distance reaches Dc By examining the behavior at Fd = 0 m, 5 m, and 10 m, we clearly observed the progression of slip weakening across the fault and verified the applicability of the LSW model at each location.

In Figure 11a, at Fd = 0 m, we observe the evolution of slip, stress, and slip rate from t = 0 ms to t = 20 ms. Slip increases steadily, while the slip rate follows a rise-and-fall pattern, peaking at approximately 1.6 m/s as the rupture accelerates, and then decaying to zero. This behavior conforms to the expected LSW dynamics, where the slip rate sharply increases as the rupture reaches Dc, followed by a gradual decrease in both slip rate and stress. The transition in stress from around 2.5 MPa (static strength) to 1.5 MPa (dynamic strength) aligns with the theoretical slip weakening mechanism. At Fd = 5 m, as shown in Fig. 11b, the peak slip rate of approximately 1.1 m/s occurs slightly later than at Fd = 0 m, indicating a temporal lag in the dynamic weakening process as rupture propagates outward from the nucleation point. The stress evolution mirrors this delay, transitioning from around 3 MPa to 1.8 MPa, with fault weakening accelerating rupture propagation. Figure 11c, at Fd =10 m, reveals a further delay in the evolution of slip and slip rate, demonstrating that the rupture process slows as it moves further along the fault. Despite the temporal lag, the overall slip and stress weakening behavior remains consistent, confirming the robustness of the LSW model across varying fault positions.

Figure S7 extends the analysis to a larger critical slip distance (Dc = 0.0015 m), revealing similar trends in slip and slip rate evolution, though with slightly reduced slip magnitudes and an extended stress weakening process. This demonstrates the sensitivity of dynamic rupture to Dc, as the larger Dc leads to slower rupture initiation and progression. The combined analysis of Fig. 11 and Fig. S6 clearly verifies the LSW effectiveness, while also highlighting the role of Dc in shaping fault dynamics. The excellent agreement between our numerical simulations and theoretical predictions further validates our choice of time-step and mesh size.

Impact of seismic waves on roadway stability

Particle velocity distribution and roadway response

Seismic waves generated by dynamic rupture can significantly impact the stability of the surrounding rock mass and the structural integrity of underground roadways. This section analyzes the distribution of particle velocity (PV) to evaluate the dynamic response of the roadway structure, with particular emphasis on the amplification effect caused by wave reflection. The peak particle velocity (PPV) refers to the maximum PV value, while the peak particle acceleration (PPA) corresponds to the maximum particle acceleration. Data were collected from multiple monitoring points along the roof (H1-H5) and the right side of the roadway (V1-V5), as shown in Fig. 12, to assess the influence of seismic wave propagation on roadway stability.

Figure 13 presents the PV distribution along the roof (H1-H5) under the conditions of D = 3 m, µs = 0.47, µd = 0.27, and Dc = 0.001 m. The maximum value for each monitoring line represents the PPV, with red arrows indicating the exact location of these maxima. The PPV values show a clear decreasing trend from H1 to H5, with H1 exhibiting a PPV of 0.40 m/s, while H5 decreases to 0.21 m/s. This significant reduction indicates the attenuation of seismic wave energy as it moves away from the roadway, with less dynamic impact observed in more distant regions.

The notably higher PPV values at H1 and H2 can be attributed to the wave reflection amplification effect. As seismic waves reach the free surface of the roadway roof, part of the wave energy is reflected back into the surrounding medium. This reflected wave interferes with the incoming wave, leading to an amplification of the dynamic response. For example, the PPV at H1 is 0.40 m/s, while at H5 it drops to 0.21 m/s, showing a reduction of more than 47%, clearly indicating that the reflection effect diminishes with increasing distance from the roadway.

Figure 14 illustrates the PV distribution along the right side of the roadway (V1-V5). Similar to the roof, PPV and PPA values decrease with distance from the roadway. However, the reduction in PPV along the sidewall is less pronounced than along the roof. For instance, V1 records a PPV of 0.49 m/s, while V5 shows a reduction to 0.36 m/s, a decrease of only 27%. This smaller reduction can be explained by the proximity of the sidewall to the seismic source, leading to less energy dissipation over the shorter distance, and thus less wave attenuation. Consequently, the reflection effect is less significant along the sidewall compared to the roof. The PPV and PPA at the observation points on the roof and right side of the roadway are summarized in Table 4.

Reflection amplification effect on roadway stability

The distribution of PPV and PPA reveals the significant influence of the reflection amplification effect on roadway stability. Monitoring points near the free surface (e.g., H1 and V1) experience higher dynamic loads due to the combined effect of incoming and reflected waves. For instance, the PPV at H1 reaches 0.40 m/s, while V1 records a PPV of 0.49 m/s, indicating elevated dynamic stresses in these areas. As the distance from the roadway increases (e.g., H5 and V5), the PPV values drop significantly due to the attenuation of seismic waves and the diminishing effect of wave reflection, leading to lower dynamic loads and improved structural stability in these regions.

In designing roadways, it is crucial to account for the reflection amplification effect, particularly along the roof. The free surface of the roof amplifies the dynamic response, especially in areas close to the roadway, such as H1 and H2, where dynamic loads are more pronounced. These regions require special attention in terms of structural design to enhance the roadway’s seismic resilience. Although the sidewall is less affected by wave reflection, it is still subjected to higher PPV and PPA values due to its proximity to the seismic source, necessitating careful consideration of the stability of V1 and V2.

The data presented in Figs. 13 and 14, and Table 4 clearly demonstrate the effects of wave reflection and seismic wave attenuation on different regions of the roadway. Analysis of PPV and PPA distributions reveals that regions near the free surface of the roadway, particularly the roof, experience amplified dynamic responses due to wave reflection. In contrast, the sidewall experiences less amplification but remains exposed to significant dynamic loads due to its proximity to the seismic source. These findings emphasize the importance of considering both reflection effects and distance from the source in designing roadway structures for enhanced seismic resilience, especially in seismically active mining environments.

Limitations

While this study provides valuable insights into ultra-close fault dynamic rupture and its impact on roadway stability, several limitations should be acknowledged.

First, the 2-D plane-strain model used, although effective in capturing fault slip behavior and seismic responses, simplifies the inherently complex three-dimensional nature of fault systems and seismic wave propagation. In reality, fault geometries and rupture propagation exhibit significant 3-D variability, which cannot be fully captured by a 2-D model. This limitation constrains the ability of the model to represent lateral and vertical fault interactions and more intricate seismic wave reflections. Future studies should incorporate full 3-D simulations to better capture stress distributions, rupture dynamics, and seismic wave interactions across the fault plane and the entire roadway system, providing a more accurate assessment of fault-induced seismic risks.

Second, a notable limitation arises from the exclusion of the plastic zone induced by roadway excavation. Excavation typically causes plastic deformation in the surrounding rock mass, which significantly alters stress redistribution and may influence fault stability39,63. By not including the plastic zone in our model, we may have overestimated roadway stability and underestimated the effects of excavation-induced deformation on fault rupture and seismic wave propagation. Future work should integrate the plastic zone to more accurately capture the interaction between excavation deformation and dynamic rupture processes.

Another limitation is the restricted range of Dc values used in this analysis. While the chosen Dc values are representative of typical fault behavior, real-world faults may exhibit a broader spectrum of Dc values due to variations in geological and mechanical properties49,64. This limited range of Dc values may constrain the study’s ability to fully explore a wide range of rupture behaviors and energy dissipation mechanisms. Expanding the range of Dc values in future research would enable a more comprehensive understanding of dynamic rupture behavior and associated seismic hazards. The pre-nucleation phase in our model, while inherently time-dependent under real mining conditions, has been approximated as a static process for computational efficiency and clarity. This simplification omits the gradual redistribution of stress over time, which could result in discrepancies when compared to actual mining scenarios. To address this limitation, future research should aim to incorporate the time-dependent characteristics of the pre-nucleation phase, enabling a more precise representation of stress evolution and rupture initiation.

Additionally, the reflection and amplification effects modeled near the excavation boundaries were based on idealized conditions assuming smooth, regular geometry. In real mining environments, roadway surfaces are often irregular, with joints and fractures that could further amplify or alter seismic wave propagation65,66,67. The assumption of smooth surfaces may oversimplify the interaction between wave reflection and excavation geometry. Future studies should incorporate more complex geometries that account for surface roughness and discontinuities, providing a more accurate assessment of seismic wave amplification and its impact on roadway stability. The conclusion that reflected waves from the roadway surface dominate PPV amplification, particularly near the roof, is specific to the geometric and material configurations of the current model. It is important to note that under different roadway geometries, fault positions, or fault-to-roadway distances, the direct contribution of seismic waves generated by the fault may surpass the effects of wave reflections. This suggests that the dominance of reflected waves is not universally applicable. Future studies should broaden the scope of analysis to encompass a wider range of fault and roadway configurations, ensuring a more generalized understanding of PPV amplification mechanisms.

Conclusion

This study provides a detailed numerical analysis of dynamic rupture induced by deep roadway excavation, focusing on near-fault dynamic rupture. By replicating and extending the model of Vardar et al. (2022), we validated our numerical approach and conducted a quantitative assessment of dynamic rupture for faults located within 5 m of the roadway.

The results show significant increases in fault slip and seismic moment when the fault is within 5 m of the roadway. For example, at D = 3 m, the peak fault slip exceeds 17.1 mm, and the seismic moment reaches 3.9 × 1010 Nm. Faults with µs = 0.27 show greater slip than those with µs = 0.37, underscoring the role of frictional properties in fault mechanics. The validation of the LSW model demonstrates its effectiveness in capturing slip weakening mechanisms and the transition from static to dynamic stress.

Wave reflection effects at the roadway surface were identified as a major contributor to PPV amplification, particularly near the roof, with PPV values of 0.40 m/s and 0.49 m/s at H1 and V1, respectively. However, further analysis indicates that the dominance of reflections is specific to the current model configuration. Under different fault geometries or fault-to-roadway distances, seismic source effects may outweigh reflections. This study highlights the need for broader investigations to generalize these findings.

In conclusion, this study provides valuable insights into seismic risks associated with ultra-close fault conditions and the role of wave reflections in roadway stability. While our findings advance the understanding of fault behavior and slip weakening mechanisms, further empirical research is needed to validate these results and support seismic-resistant designs in faulted geological environments.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author upon request. We enthusiastically invite readers to replicate our research and have included a sample of the code utilized in this study to aid in this endeavor. For access to the full set of code, please reach out to the corresponding author, who will gladly provide the necessary resources.Availability: https://github.com/liyatao2020/roadway-dynamic.

Change history

10 May 2025

The original online version of this Article was revised: The original version of this Article contained an error in Affiliation 1, which was incorrectly given as ‘School of Resources and Safety Engineering, School of Resources and Safety Engineering, Beijing, 100083, China’. The correct affiliation is listed here: ‘School of Resources and Safety Engineering, University of Science and Technology Beijing, Beijing 100083, China’. The original Article has been corrected.

References

Ranjith, P. G. et al. Opportunities and challenges in deep mining: a brief review. Eng. (Beijing China). 3 (4), 546–551. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ENG.2017.04.024 (2017).

Wei, C., Zhang, C., Canbulat, I. & Wanpeng, H. Numerical investigation into impacts of major fault on coal burst in longwall mining; a case study. Int. J. Rock. Mech. Min. Sci. (Oxford England: 1997). 147, 104907. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2021.104907 (2021).

Agrawal, H., Durucan, S., Cao, W., Korre, A. & Shi, J. Rockburst and gas outburst forecasting using a probabilistic risk assessment framework in longwall top coal caving faces. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 56(10), 6929–6958. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-022-03076-3 (2023).

Jiang, Y., Zhao, Y., Wang, H. & Zhu, J. A review of mechanism and prevention technologies of coal bumps in China. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 9(1), 180–194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrmge.2016.05.008 (2017).

Jiang, L. et al. Dynamic analysis of the rock burst potential of a longwall panel intersecting with a fault. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 53(4), 1737–1754. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-019-02004-2 (2020).

Du, K., Bi, R., Khandelwal, M., Li, G. & Zhou, J. Occurrence mechanism and prevention technology of rockburst, coal bump and mine earthquake in deep mining. Geomech. Geophys. Geo-Energy Geo-Resources. 10(1), 1–35. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40948-024-00768-8 (2024).

Li, Y., Fukuyama, E. & Yoshimitsu, N. Mining-induced fault failure and coseismic slip based on numerical investigation. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 83(10), 386. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10064-024-03888-3 (2024).

Kang, H., Gao, F., Xu, G. & Ren, H. Mechanical behaviors of coal measures and ground control technologies for China’s deep coal mines - a review. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 15(1), 37–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrmge.2022.11.004 (2023).

Wei, C., Zhang, C., Canbulat, I., Song, Z. & Dai, L. A review of investigations on ground support requirements in coal burst-prone mines. Int. J. Coal Sci. Technol. 9(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40789-022-00485-1 (2022).

Yan, Z. et al. Fracturing evolution analysis of beishan granite under true triaxial compression based on acoustic emission and strain energy. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 117, 150–161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2019.03.029 (2019).

Dai, L. et al. Quantitative mechanism of roadway rockbursts in deep extra-thick coal seams; theory and case histories. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 111, 103861. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tust.2021.103861 (2021).

Dou, L., Mu, Z., Li, Z., Cao, A. & Gong, S. Research progress of monitoring, forecasting, and prevention of rockburst in underground coal mining in China. Int. J. Coal Sci. Technol. 1(3), 278–288. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40789-014-0044-z (2014).

Li, Y., Fukuyama, E., & Yoshimitsu, N. (2025). Comprehensive 3-D modeling of mining-induced fault slip: Impact of panel length, panel orientation and far-field stress orientation. Rock Mechanics and Rock Engineering. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-025-04469-w

Kong, P., Jiang, L., Shu, J. & Wang, L. Mining stress distribution and fault-slip behavior: a case study of fault-influenced longwall coal mining. Energies 12(13), 2494. https://doi.org/10.3390/en12132494 (2019).

Kong, P., Wang, C., Xing, L., Liang, M. & He, J. Study on the fault slip rule and the rockburst mechanism induced by mining the panel through fault. Geomech. Geophys. Geo-Energy Geo-Resources. 9(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40948-023-00697-y (2023).

He, S. et al. Coupled mechanism of compression and prying-induced rock burst in steeply inclined coal seams and principles for its prevention. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 98, 103327. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tust.2020.103327 (2020).

Zhu, Q., Zhao, X. & Westman, E. Review of the evolution of mining-induced stress and the failure characteristics of surrounding rock based on microseismic tomography. Shock Vib. 2021(1) https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/2154857 (2021).

Zhang, C., Feng, X., Zhou, H., Qiu, S. & Yang, Y. Rock mass damage induced by rockbursts occurring on tunnel floors; a case study of two tunnels at the jinping II hydropower station. Environ. Earth Sci. 71(1), 441–450. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12665-013-2451-7 (2014).

Zhang, C., Liu, N. & Chu, W. Key technologies and risk management of deep tunnel construction at jinping II hydropower station. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 8(4), 499–512. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrmge.2015.10.010 (2016).

Liu, L., Wang, X., Zhang, Y., Jia, Z. & Duan, Q. Tempo-spatial characteristics and influential factors of rockburst: a case study of transportation and drainage tunnels in jinping II hydropower station. J. Rock. Mech. Geotech. Eng. (Online). 3(2), 179–185. https://doi.org/10.3724/SP.J.1235.2011.00179 (2011).

Galvin, J. M. Ground Engineering: Principles and Practices for Underground Coal Mining. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-25005-2 (Springer, 2016).

Li, Y., Gao, X., Yang, J. & Bai, E. Quantitative 3-D investigation of faulting in deep mining using Mohr–coulomb criterion and slip weakening law. Geomech. Geophys. Geo-Energy Geo-Resources. 11(1) https://doi.org/10.1007/s40948-024-00928-w (2025).

Manouchehrian, A. & Cai, M. Numerical modeling of rockburst near fault zones in deep tunnels. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 80, 164–180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tust.2018.06.015 (2018).

Wang, H. et al. Characteristic of stress evolution on fault surface and coal bursts mechanism during the extraction of longwall face in yima mining area, China. J. Struct. Geol. 136, 104071. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsg.2020.104071 (2020).

Li, Y. Spatial Distribution of Strain energy Changes due to Mining-Induced Fault Coseismic Slip: Insights from a Rockburst at the Yuejin Coal Mine, China https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-024-04232-7 (Rock Mechanics and Rock Engineering, 2024).

Cao, M., Wang, T. & Li, K. A numerical analysis of coal burst potential after the release of the fault-slip energy. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 56(5), 3317–3337. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-023-03224-3 (2023).

Chen, L., Shen, B. & Dlamini, B. Effect of faulting on coal burst – A numerical modelling study. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 28(5), 739–743. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmst.2018.07.010 (2018).

Li, Z. et al. Investigation and analysis of the rock burst mechanism induced within fault-pillars. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. 70, 192–200 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2014.03.014 (2014).

Wang, G. et al. Behaviour and bursting failure of roadways based on a pendulum impact test facility. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 92, 103042. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tust.2019.103042 (2019).

Wang, H. et al. Mechanical model for the calculation of stress distribution on fault surface during the underground coal seam mining. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. 144, 104765 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2021.104765 (2021).

Peter, Z. et al. Geotechnical risk management to prevent coal outburst in room-and-pillar mining. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 26(1), 9–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmst.2015.11.003 (2016).

Li, B. et al. Characteristics of coal mining microseismic and blasting signals at qianqiu coal mine. Environ. Earth Sci. 76(21), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12665-017-7070-2 (2017).

Vardar, O., Zhang, C., Canbulat, I. & Hebblewhite, B. A semi-quantitative coal burst risk classification system. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 28(5), 721–727. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmst.2018.08.001 (2018).

Li, Y. Heterogeneous layer effects on mining-induced dynamic ruptures. Comput. Geosci. 195, 105776. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cageo.2024.105776 (2025).

Xu, S. Q. et al. Fault strength and rupture process controlled by fault surface topography. Nat. Geosci. 16(1), 94–100. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-022-01093-z (2023).

Yamashita, F. et al. Rupture preparation process controlled by surface roughness on meter scale laboratory fault. Tectonophysics 733, 193–208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tecto.2018.01.034 (2018).

Liu, P. et al. Physical similarity simulation of deformation and failure characteristics of coal-rock rise under the influence of repeated mining in close distance coal seams. Energies (Basel). 15(10), 3503. https://doi.org/10.3390/en15103503 (2022).

Ma, S. et al. Experimental investigation on stress distribution and migration of the overburden during the mining process in deep coal seam mining. Geoenvironmental Disasters. 10(1), 24–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40677-023-00253-6 (2023).

Vardar, O., Wei, C., Zhang, C. & Canbulat, I. Numerical investigation of impacts of geological faults on coal burst proneness during roadway excavation. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 81(1) https://doi.org/10.1007/s10064-021-02508-8 (2022).

Li, Y., Yang, J. & Gao, X. Fault slip amplification mechanisms in deep mining due to heterogeneous geological layers. Eng. Fail. Anal. 169 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engfailanal.2024.109155 (2025).

Cai, W., Dou, L., Si, G. & Hu, Y. Fault-induced coal burst mechanism under mining-induced static and dynamic stresses. Eng. (Beijing China). 7(5), 687–700. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eng.2020.03.017 (2021).

Sainoki, A. & Mitri, H. S. Dynamic behaviour of mining-induced fault slip. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 66, 19–29 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2013.12.003 (2014).

Sainoki, A. & Mitri, H. S. Evaluation of fault-slip potential due to shearing of fault asperities. Can. Geotech. J. 52(10), 1417–1425. https://doi.org/10.1139/cgj-2014-0375 (2015).

Sainoki, A. & Mitri, H. S. Dynamic modelling of fault slip induced by stress waves due to stope production blasts. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 49(1), 165–181. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-015-0721-2 (2016).

Sainoki, A. & Mitri, H. S. Quantitative analysis with plastic strain indicators to estimate damage induced by fault-slip. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 10(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrmge.2017.06.001 (2018).

Li, Y. Fault quasi-static and dynamic ruptures in deep coal mining: impacts on working faces. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 83(12), 515. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10064-024-04017-w (2024).

Qiu, P., Ning, J., Wang, J., Hu, S. & Li, Z. Mitigating rock burst hazard in deep coal mines insight from dredging concentrated stress; a case study. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 115, 104060. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tust.2021.104060 (2021).

Day, S. M., Dalguer, L. A., Lapusta, N. & Liu, Y. Comparison of finite difference and boundary integral solutions to three-dimensional spontaneous rupture. J. Phys. Res. 110(B12), B12307. https://doi.org/10.1029/2005JB003813 (2005). -n/a.

Buijze, L., van den Bogert, P. A. J., Wassing, B. B. T. & Orlic, B. Nucleation and arrest of dynamic rupture induced by reservoir depletion. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth. 124(4), 3620–3645. https://doi.org/10.1029/2018JB016941 (2019).

Wei, C., Zhang, C. & Canbulat, I. Numerical analysis of fault-slip behaviour in longwall mining using linear slip weakening law. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 104 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tust.2020.103541 (2020).

Aagaard, B. T., Knepley, M. G. & Williams, C. A. A domain decomposition approach to implementing fault slip in finite-element models of quasi-static and dynamic crustal deformation. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth. 118(6), 3059–3079. https://doi.org/10.1002/jgrb.50217 (2013).

Aagaard, B. T., Knepley, M. G. & Williams, C. A. PyLith v4.0.0. Comput. Infrastruct. Geodyn. (2023).

Uenishi, K. & Rice, J. R. Universal nucleation length for slip-weakening rupture instability under nonuniform fault loading. J. Geophys. Res. 108(B1), 2042–n/a https://doi.org/10.1029/2001JB001681 (2003).

Palmer, A. C. & Rice, J. R. The growth of slip surfaces in the progressive failure of over-consolidated clay. Philosophical Trans. Royal Soc. Lond. Ser. A: Math. Phys. Sci. 332(1591), 527–548. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspa.1973.0040 (1973).

Courant, R., Friedrichs, K. & Lewy, H. Uber die partiellen Differenzengleichungen Der Mathematischen Physik. Math. Ann. 100, 32–74 (1928).

Saito, T. & Noda, A. Strain energy released by earthquake faulting with random slip components. Geophys. J. Int. 220(3), 2009–2020. https://doi.org/10.1093/gji/ggz561 (2019).

Salamon, M. D. G. Energy considerations in rock mechanics; fundamental results. J. S. Afr. Inst. Min. Metall. 84(8), 233–246 (1984).

Li, Y., & Gao, X. (2025). Assessment of variations in shear strain energy induced by fault coseismic slip in deep longwall mining. International Journal of Coal Science & Technology, 12(3). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40789-024-00742-5

Kanamori, H. & Anderson, D. L. Amplitude of the earth’s free oscillations and long-period characteristics of the earthquake source. J. Phys. Res. 80(8), 1075–1078. https://doi.org/10.1029/JB080i008p01075 (1975).

Wilkinson, M. et al. Slip distributions on active normal faults measured from LiDAR and field mapping of geomorphic offsets: an example from L’aquila, Italy, and implications for modelling seismic moment release. Geomorphology 237, 130–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geomorph.2014.04.026 (2015).

Kubota, T., Saito, T., Suzuki, W. & Hino, R. Estimation of seismic centroid moment tensor using ocean bottom pressure gauges as seismometers. Geophys. Res. Lett. 44(21), 10907. https://doi.org/10.1002/2017gl075386 (2017).

Geller, R. J. Scaling relations for earthquake source parameters and magnitudes. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 66(5), 1501–1523. https://doi.org/10.1785/BSSA0660051501 (1976).

Fu, T., Xu, T., Heap, M. J., Meredith, P. G. & Mitchell, T. M. Mesoscopic time-dependent behavior of rocks based on three-dimensional discrete element grain-based model. Comput. Geotech. 121, 103472. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compgeo.2020.103472 (2020).

Venegas-Aravena, P., Crempien, J. G. F. & Archuleta, R. J. Fractal spatial distributions of initial shear stress and frictional properties on faults and their impact on dynamic earthquake rupture. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 114(3), 1444–1465. https://doi.org/10.1785/0120230123 (2024).

Czarny, R. et al. Dispersive seismic waves in a coal seam around the roadway in the presence of excavation damaged zone. Int. J. Rock. Mech. Min. Sci. (Oxford England: 1997). 148, 104937. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2021.104937 (2021).

Liu, L. et al. An inverted heterogeneous velocity model for microseismic source location in deep buried tunnels. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 56(7), 4855–4880. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-023-03305-3 (2023).

Arts, J. P. B., Niemeijer, A. R., Drury, M. R., Willingshofer, E. & Matenco, L. C. The frictional strength and stability of spatially heterogeneous fault gouges. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 628, 118586. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2024.118586 (2024).

Acknowledgements

During the preparation of this manuscript, we benefited greatly from the invaluable guidance of Prof. Eiichi Fukuyama and Prof. Cai Wu. We also sincerely appreciate Dr. Shibo Xu for his critical review, which significantly contributed to improving the quality of the manuscript. We extend our heartfelt gratitude to the two anonymous reviewers for their professional, constructive, and insightful comments. We thank the Computational Infrastructure for Geodynamics (http://geodynamics.org) which is funded by the National Science Foundation under awards EAR-0949446, EAR-1550901, and EAR-2149126.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yatao Li: Design research methods, experimental design, etc. Data acquisition, processing and analysis. Write the first draft. Participate in discussions and revisions. Responsible for the coordination of research. Xuehong Gao: Responsible for the planning, design and implementation of the entire study. Ensure the integrity and accuracy of the research. Revise paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, Y., Gao, X. Quantitative analysis of ultra-close fault dynamic rupture and seismic risks in deep roadway excavation. Sci Rep 15, 8891 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86967-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86967-z

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Shear strain energy related to mining induced fault slip and its implications for rockbursts

Scientific Reports (2025)