Abstract

A Gemini cationic surfactant was synthesized through an aldehyde-amine condensation reaction to address challenges related to bacterial corrosion and foaming during shale gas extraction. This treatment agent exhibits sterilization, corrosion mitigation, and foaming properties. The mechanism of action was characterized through tests measuring surface tension, particle size, sterilization efficacy, corrosion mitigation efficiency, and foaming behavior. Results from the surface tension test indicate that at 60 °C, surfactants with a low carbon chain structure achieve the lowest surface tension of 32.61 mN/m at the critical micelle concentration. Particle size distribution (PSD) tests reveal that within the 1–10 critical micelle concentration range, three types of surfactants can form aggregates through self-assembly, with a PSD range of 100–400 nm. Antibacterial performance tests demonstrate that a concentration of 0.12 mmol/L at 20–60 °C achieves a bactericidal rate exceeding 99%, maintained even after 24 h of contact. The bactericidal effect is enhanced under acidic and alkaline conditions. Corrosion mitigation tests show that at 50 °C, the corrosion mitigation rate reaches an optimal value of over 70%. Bubble performance evaluation results suggest that the optimal surfactant concentration is 1 mmol/L at 60 °C, exhibiting resistance to mineralization up to 200 g/L. The development of this surfactant establishes a foundation for effectively addressing issues related to bacterial corrosion and wellbore fluid encountered in shale gas wells.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the process of shale gas development, it is necessary to create gas flow channels through hydraulic fracturing to create fractures. The objective is to induce fractures and augment the permeability channels within the gas reservoir1. During the process, original microbial bacteria from the formation enter the wellbore during the backflow of fracturing fluid, influenced by the fluid’s flushing effects. When exposed to temperatures between 20 and 60 °C, bacteria transition from a dormant state under high temperature and pressure to an awakened state, regaining activity2. Notably, sulfate-reducing bacteria have the capacity to metabolize and produce H2S, which, when combined with CO2 from the formation, can lead to severe corrosion in the wellbore. After long-term development of shale gas, foam drainage gas production becomes imperative for increasing and stabilizing production. However, the issue of bacterial corrosion in the wellbore necessitates the use of bactericides along with surfactants. This combination helps slow down the corrosion damage caused by bacteria in the wellbore, preventing shutdown maintenance due to corrosion. Hence, developing a high-performance bactericide holds significant importance in shale gas extraction.

In addressing the aforementioned challenges posed by corrosion, scholars have undertaken a series of studies focusing on the development of bactericides for the exploitation of shale gas. Shale gas bactericides commonly employed comprise both oxidizing and non-oxidizing types3,4. The oxidizing bactericides, including hydrogen peroxide, ozone, and halogen-containing compounds, primarily utilize potent oxidizing properties to dismantle the cell walls or peptide bonds within protein molecules of microorganisms. This results in the rupture and loss of bacterial cell activity5,6. However, due to their corrosive impact on operational equipment and the elevated risk of environmental pollution arising from their derivative by-products, their widespread use has been limited.

Non-oxidizing bactericides, on the other hand, encompass quaternary ammonium salt cationic surfactants and organic aldehydes7,8. Among these, quaternary ammonium salt cationic surfactants predominantly adhere to anionic bacteria through electrostatic and hydrogen bonding, altering the hydrophobicity of their surface. This leads to lysis, ultimately causing cytoplasmic leakage and cell lysis. These surfactants offer the advantages of being cost-effective, having a straightforward preparation method, and demonstrating a favorable short-term effect9. Consequently, they continue to be extensively utilized in the treatment of oilfield wastewater. Organic aldehyde bactericides, such as glutaraldehyde10, primarily disrupt bacterial cell walls through aldol condensation reactions. They interact with intracellular proteins, polypeptide sugars, and other components, inducing coagulation and effectively inhibiting DNA synthesis11. However, these bactericides exhibit limited penetration, prompting their combination with quaternary ammonium salt cationic bactericides to achieve enhanced penetration and sterilization effects. Furthermore, this material is associated with potent toxic side effects and poses a significant risk of causing pollution damage to soil and groundwater.

The primary emphasis in research on oilfield bactericides revolves around the formulation of a diverse array of treatment agents. Additionally, the exploration encompasses graft modification using quaternary ammonium salt bactericides12. Nevertheless, a challenge arises from the poor compatibility between existing bactericides and foaming surfactants. Bactericides find their primary application in ground pipelines, necessitating the mitigation of their foaming tendencies. Consequently, this leads to an inadequate foaming performance of the composite solution. While certain quaternary ammonium cationic surfactants exhibit both bactericidal properties and satisfactory foaming performance, their high critical micelle concentration and insufficient adsorption capacity pose concerns. Prolonged and widespread usage may easily lead to bacterial resistance13.

Given the inadequacies observed in existing bactericides concerning compatibility, anti-corrosion, and foaming performance, we endeavored to enhance these properties by formulating a Gemini surfactant. The synthesis of this surfactant, boasting bactericidal, corrosion inhibition, and foaming attributes, involves the utilization of aldehyde amine condensation reactions. The incorporation of azomethyl groups enhances the adsorption efficiency. The structural characteristics of this energy group were elucidated through infrared analysis. To unveil the mechanism of action of the novel surfactant, surface tension and particle size testing were conducted. The potential applications of this material were validated through sterilization and foaming performance tests.

Materials and methods

Materials

Sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) and Ethylenediamine (> 99%) were procured from Aladdin Reagents Co., Ltd. Pyridine-4-carbaldehyde (98%) and anhydrous ethanol (AR, water ≤ 0.3%) were acquired from Xilong Scientific Co., Ltd. 1-Bromooctane, 1-bromohexadecane, and 1-bromo-1-octadecane were obtained from Guangdong Wengjiang Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. Deionized water was prepared utilizing the EK-Exceed series of ultrapure water machines. Bacterial culture media, namely sulfate-reducing bacteria (SRB), Saprophytic Bacteria (TGB), and iron bacteria (IB), were sourced from Beijing Huaxing Chemical Reagent Factory. The experimental raw materials do not require purification.

Preparation of surfactant

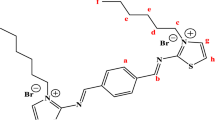

To perform the aldime condensation reaction, 0.05 mol of pyridine-4-carbaldehyde and an equal amount of ethylenediamine were dissolved in anhydrous ethanol. The solution was stirred at a rate of 200 revolutions per minute (r/min) for 3 h (30 °C). The Schiff base product was obtained via rotary evaporation. The surplus reactants were eliminated through ethanol recrystallization.

For the subsequent reaction, 0.02 mol of the purified Schiff base product underwent a reaction with 0.04 mol of alkyl bromide featuring various hydrocarbon chain lengths. These substances were co-dissolved in 200 mL of anhydrous ethanol and agitated at a speed of 300 r/min for 2 h at 60 °C. The resulting product was subjected to drying through rotary evaporation, washed thrice with ether, and subsequently dried at room temperature. The chemical progression of the reaction is depicted in Fig. 1.

Performance characterization

FT-IR

The 2 mg sample was blended with 200 mg of potassium bromide powder and finely ground in an agate mortar. Subsequently, the mixture underwent compression at 5 MPa for 1 min using an oil press to yield a transparent ingot. The ensuing sample underwent analysis utilizing a Bruker Tango near-infrared spectrometer.

Surface tension

A specific concentration of surfactant solution was prepared and the Kruss surface tension instrument was employed to conduct the test at room temperature. Preceding the examination, the platinum plate underwent a thorough rinse with deionized water, followed by complete drying through burning. Subsequent to the successful completion of cleanliness test, the surface tension test was conducted on the surfactant solution.

PSD

The PSD of the surfactant solution was examined utilizing the BI-200SM equipment. The testing of samples took place at room temperature.

Bactericidal performance

Utilizing the extinction dilution method in conjunction with the national standard SY/T5329-2012, we investigated the antibacterial characteristics of surfactants14. The assessed bacterial strains comprised sulfate-reducing bacteria, saprophytes, and iron bacteria. Bacterial cultivation was conducted at a temperature of 30 °C. The counting procedure encompassed five dilution stages, with each sample undergoing duplicate testing.

In order to determine the range of bacterial content, the sample is divided into five different dilution levels, which need to be sorted in descending order of dilution degree. If the results show bacterial growth in bottle one, while there is no bacterial growth in the other four higher dilution bottles, it can be inferred that the bacterial content ranges from 1/mL to 10/mL. On the contrary, if bacterial growth occurs in the second bottle, the range of bacterial content may be 10 to 100 per mL. By analogy, the bacterial content can be obtained. The calculation result of sterilization rate is shown in Eq. (1).

Where, Y is the bactericidal rate. N1 is the bacterial content after adding fungicides. N0 is the bacterial content without adding fungicides.

Corrosion inhibition performance

Preceding the tests, N80 steel coupons underwent pretreatment with ethanol and acetone. The sample volume for testing was maintained at 30 mL per square centimeter of the coupon’s surface area. The blank sample consisted of uninhibited formation water solution without surfactant. According to the standard of GB/T 18,175 − 2014, the assessment of the sample’s corrosion inhibition efficacy was based on the comparison of corrosion rates after a 72-hour exposure period by using N80 sheet15.

Foaming performance

Utilizing the national standard Q/SY 1815–2015, we conducted tests on the foaming and foam stability properties of surfactants, as outlined by Xiong et al.16. The initial and 5-minute heights of foam in surfactant solutions were assessed using a Ross-Miles foam meter. The sample volume for the tests was set at 250 mL, and the testing temperature maintained at 90 °C. Throughout the experiment, 200 mL of the sample was dispensed into a pipette, with 50 mL of the solution poured into the base of the Ross-Miles meter. The liquid from the pipette was poured in a vertical manner from a height of 900 mm, and the timer was initiated upon complete solution descent. Subsequently, the foam height was measured.

Results and discussions

Analysis of FT-IR

To assess the production of corresponding products in the chemical reaction process, an analysis of the structural changes in functional groups was conducted using infrared testing.

As illustrated in Fig. 2, the distinctive peak of intermediate Schiff base product -C = N- emerges at 1656 cm−1. The -NH2 characteristic peak at 3280 cm−1 in the reactant, as well as the aldehyde’s C = O stretching vibration peaks at 1708 cm−1 and 1670 cm−1, are notably absent in intermediate product. This observation signifies the formation of a Schiff base structure within the intermediate product17. In the final product’s infrared spectrum, the C-H stretching vibration peak of the saturated hydrocarbon -CH3 manifests around 2971 cm−1, providing evidence of the presence of a long-chain alkane structure.

Analysis of surface tension

The test results of surface tension are shown in Fig. 3. As illustrated in Fig. 3, critical micelle concentration (CMC) decreases as the temperature increases, accompanied by a concurrent decrease in surface tension at this concentration. This phenomenon arises due to the diminishing interaction between surfactants and water molecules as temperature rises. The decline in hydration specifically at the hydrophilic end facilitates the formation of micelles by surfactants, while the disruption of hydration structures at the hydrophobic end hinders micelle formation18. The impact of elevated temperature on the hydration of surfactant hydrophilic ends is more pronounced. Furthermore, the disruption of hydration structures increases the hydrophobicity of surfactants and ultimately realized as a decrease in surface tension.

The CMC decreases as the tail chain length increases, while the surface tension at this concentration gradually rises. When the carbon chain length increases from 8 to 16, the surface tension decreases by an average of 11% under conditions of 40–60℃. The augmentation in the tail chain signifies an escalation in hydrophobic characteristics, resulting in higher aggregation and formation of micelles of surfactant molecules in aqueous solutions19. Nonetheless, surfactant become more densely packed at the interface with longer hydrophobic carbon chains. It results from the expansion of the hydrophobic carbon chain, consequently causing an elevation in surface tension. Hence, there is a concurrent decrease in CMC and an increase in surface tension.

Analysis of PSD

High concentration surfactants can produce different aggregation structures, including rods, spheres, and vesicles. To delve deeper into the examination of the structural composition of surfactant self-assemblies, dynamic light scattering was employed for measuring their hydrodynamic radius.

As illustrated in Fig. 4, an elevation in surfactant concentration corresponds to a gradual augmentation in particle size. This phenomenon can be attributed to alterations in molecular interactions and aggregation states induced by variations in surfactant content20. The interactions among surfactant exhibit a weakened nature at low concentration, with the molecules predominantly existing as single entities dispersed in water. The interactions between surfactant progressively intensify at high concentration, prompting the formation of micelles or aggregates. This self-assembly process contributes to a gradual enlargement in particle size.

Furthermore, the aggregation state also plays a role in influencing particle size. As surfactant concentration increases, the amount of aggregated surfactants increases, leading to an increase in particle size.

PSD of surfactants gradually expands at equivalent concentrations with the increase of hydrophobic tail chains. The heightened hydrophobicity resulting from more hydrophobic carbon chains in surfactants enhances their strength. This implies that a greater number of surfactant molecules can coalesce, giving rise to a more substantial hydrophobic core. This enlarged hydrophobic core, in turn, has the capacity to attract and aggregate additional surfactant molecules, forming larger micelles, as noted by Tavano et al.21. Consequently, surfactants possessing more hydrophobic carbon chains exhibit the capability to create micelles comprising a higher number of surfactant molecules, thereby elevating the hydrodynamic radius of the aggregates, as emphasized by Cuenca et al.22.

Analysis of bactericidal performance

During the foam drainage gas recovery process, the antibacterial performance is affected by temperature and pH of the formation water, as well as the concentration, time, and carbon chain length of the surfactant. To delve deeper into the antibacterial effects of surfactants during wellbore dosing, we conducted pertinent experimental analyses.

As illustrated in Fig. 5a, surfactant exerts the most pronounced influence on SRB. At lower concentrations, a bactericidal efficacy exceeding 96% can be attained (test conditions: 30 °C, contact time of 1 h, pH = 7). As the surfactant concentration rises, the bactericidal rates of the three bacteria stabilize when the concentration surpasses 0.12 mmol/L, consistently exceeding 99%. Under conditions of elevated concentration, a substantial quantity of surfactant molecules can undergo electrostatic adsorption onto the cell membrane surface23. This phenomenon induces cell membrane rupture and facilitates surfactant molecule penetration, resulting in bacterial inactivation.

Figure 5b shows that the duration of contact exerts a noteworthy influence on the bactericidal efficacy of TGB under specific test conditions (30 °C, concentration of 1 mmol/L, pH = 7). Following a 4-hour contact period, the bactericidal rates for all three bacteria surpass 99%. Extending the contact time to 6–8 h achieves a 100% bactericidal rate. Subsequent to this timeframe, the bactericidal rate gradually diminishes. Even at the 24-hour mark, the bactericidal rate remains above 99%, indicating the enduring bactericidal effect and potent capability of this surfactant in inhibiting bacterial resistance.

Considering the pH range of the formation water, we conducted antibacterial performance tests within the pH range of 5 to 9. The testing conditions included a temperature of 30 °C, a contact time of 1 h, and a concentration of 1 mmol/L. Figure 5c illustrates that under extreme pH conditions, the surfactant exhibits a higher bactericidal rate at pH = 5 and 9, attributed to the low survival rate of bacteria.

At pH = 6, the weak acidic environment weakens the positive charge carried by the cationic group. However, the impact of H+ on bacteria outweighs its reduction on surfactant adsorption, resulting in a consistently stable antibacterial performance. Under weakly alkaline conditions, the quaternary ammonium salt forms a quaternary ammonium hydroxide with OH−, allowing for complete ionization and stability in the solution. Moreover, excess OH− has the additional benefit of disrupting bacterial activity.

As illustrated in Fig. 5d, when subjected to temperatures between 20 °C and 60 °C, the surfactant exhibits a bactericidal efficacy exceeding 95% (experimental conditions: pH = 7, 1-hour contact time, concentration of 1 mmol/L). It has been observed that bacterial activity diminishes above 60 °C4. Within the temperature range conducive to bacterial activity, this surfactant demonstrates commendable temperature tolerance. In the absence of the surfactant, bacterial activity experiences a significant decline at 60 °C with increasing temperature. Upon the addition of the surfactant, a robust bactericidal effect is maintained at temperatures where elevated temperatures do not markedly impact its efficacy (20–50 °C). Elevated temperatures facilitate the diffusion of surfactants in the solution and expedite their binding kinetics with bacteria.

Figure 5e shows that bactericidal rate of surfactant gradually increases with the increase of hydrophobic carbon chain (30 °C, pH = 7, a contact time of 1 h, and a concentration of 1 mmol/L). This decline is attributed to the longer carbon chains causing inadequate solubility in aqueous solutions. Furthermore, the augmentation in carbon chain length diminishes the CMC, leading to a reduction in surfactant concentration at the interface, ultimately resulting in a decrease in the bactericidal rate24.

Analysis of corrosion inhibition performance

It was assessed by examining its corrosion inhibition rate across various temperature and concentration conditions.

As illustrated in Fig. 6a, the corrosion inhibition rate attains its optimal value, surpassing 70%, at 50 °C (with a tested concentration of 0.5 mmol/L). Below this temperature threshold, an increase in temperature will enhance the overall corrosion inhibition effect. However, beyond this temperature point, the increased temperature will lead to an increase in the corrosion reaction rate25.

As illustrated in Fig. 6b, an elevation in surfactant concentration results in the corrosion inhibition rate reaching a plateau at 1 mmol/L. Beyond this concentration, there is a marginal decline in the corrosion inhibition rate, as observed at a tested temperature of 20 °C. In instances of low corrosion inhibitor concentrations, the inhibitor molecules may inadequately shield the metal surface, causing partial exposure to the corrosive medium and consequently diminishing the corrosion inhibition effect26. Conversely, under high concentration conditions, this heightened coverage effectively insulates the metal from the corrosive medium, thereby enhancing corrosion inhibition performance.

Based on the theory of adsorption equilibrium, the process of corrosion inhibitor adsorption onto metal surfaces is a dynamic equilibrium process. At low concentrations of corrosion inhibitors, the adsorption equilibrium may lean more toward desorption, resulting in the detachment of corrosion inhibitors. As the concentration increases, the adsorption equilibrium shifts towards adsorption, facilitating the stable adsorption.

At elevated concentrations, potential interactions among molecules of corrosion inhibitors, such as aggregation and association, could influence their distribution and adsorption behavior on the metal surface27. Maintaining an optimal concentration of corrosion inhibitors facilitates the formation of a stable adsorption layer, but excessive concentration does not significantly improve the overall corrosion inhibition performance.

Figure 6c shows the corrosion inhibition mechanism of gemini surfactant. It can tightly adsorb and arrange on the metal surface, thereby hindering the contact of water molecules. As the tail chain grows, corrosion inhibition performance shows a gradual improvement. The hydrophobic tail chains present in corrosion inhibitors can establish robust hydrophobic interactions with the metal surface. This alteration in the wettability subsequently diminishes the adhesion of corrosive medium to the metal surface28. Additionally, the extended hydrophobic tail chains in corrosion inhibitors have the capability to self-assemble into micellar structures, facilitating the adsorption and film formation process on the metal surface. Consequently, this contributes to an enhanced corrosion inhibition effect.

Analysis of foaming performance

Analyzing the effect of water drainage and gas recovery can be achieved by assessing the foaming performance of surfactants under formation temperature and salinity conditions.

As illustrated in Fig. 7a, the foaming performance attains a stable state at 1 mmol/L. The initial foam measures 108 mm, and the 5-minute foam registers at 82 mm (tested at 60 °C and salinity of 100 g/L, carbon chain length is 8). With the escalating surfactant concentration, there is a corresponding increase in adsorption at the liquid-gas interface, resulting in a more pronounced reduction in surface tension. This facilitates the formation and stabilization of bubbles. Moreover, the adsorption of surfactant molecules generates a molecular film, endowed with a specific strength and elasticity that can withstand external pressure on the bubbles, thereby preserving foam stability29. The strength and elasticity of molecular film improve with rises of surfactant concentration, thereby augmenting foaming performance. Additionally, this surfactant exhibits self-assembly capabilities and can construct multi-layer structure at the liquid-gas interface. This structure further reinforces foam stability.

As illustrated in Fig. 7b, the foaming performance attains its optimal level at 40 °C with a noticeable increase in temperature. The initial foam measures 141 mm, while the 5-minute foam, under a tested concentration of 3 mmol/L and a salinity of 100 g/L, registers at 117 mm. At lower temperatures, the activity of surfactant of liquid-gas interface weakens, leading to inadequate foaming performance. By judiciously elevating the temperature, the molecular motion speed of surfactants can be heightened, thereby augmenting their adsorption and diffusion on the liquid-gas interface30. This, in turn, aids in reducing surface tension and enhancing foaming performance. However, excessively high temperatures may impact the stability of surfactants, potentially causing the rupture or alteration of chemical bonds within surfactant molecules and the subsequent loss of their original foaming performance.

As illustrated in Fig. 7c, the foaming efficacy of surfactants exhibits a gradual decline with escalating salinity levels. Upon reaching a salinity of 200 g/L, the foam heights register at 103 mm and 82 mm at the starting time and 5 min later (testing at concentration of 3 mmol/L and 60 °C, carbon chain length is 8). In adherence to evaluation standards, achieving values surpassing 120 mm and 80 mm proves more conducive to satisfying field application requirements. The escalation in salinity corresponds to an augmentation in surface tension, concomitant with a reduction in solubility. Moreover, salt ions present in formation water may vie with surfactant molecules for adsorption on the liquid-gas interface, commandeering adsorption sites and influencing the configuration and adsorption state of surfactant molecules at the liquid-gas interface, thereby impacting foaming performance31. Certain salt ions may precipitate as insoluble compounds with surfactant molecules, resulting in foam breakdown or diminished stability.

Figure 7d indicates that the increase in tail chains correlates with a gradual improvement in the foaming performance of surfactants (tested under conditions of 60 °C temperature, 100 g/L salinity, and 3 mmol/L concentration). Figure 7e shows the stable foam mechanism of surfactants. Combined with the surface tension test results, it reveals that an elongation of the hydrophobic tail chain facilitates a more effective reduction in surface tension at the gas-liquid interface. The extended hydrophobic tail chains exhibit the ability to form organized arrangements or aggregates on the bubble film, thereby restricting the mutual merging and deformation of bubbles. This mechanism contributes to the preservation of the stability of the foam structure. Longer hydrophobic tail chains generate a more viscous interfacial film on the gas-liquid interface, which, in turn, enhances the elasticity of the foam.

Comparative analysis of foam micro morphology of surfactant synthesized by 1-bromo-1-octadecane and traditional surfactant SDS (60 °C temperature, 100 g/L salinity, and 3 mmol/L concentration). As shown in Fig. 7f, during the same period, the bubbles formed by the new surfactant can maintain small size and dense arrangement, and their bubble coalescence rate is slow, indicating that they have good stability.

Conclusions

A surfactant with bactericidal and corrosion-inhibiting properties was synthesized, primarily functioning through the eradication of bacteria via cationic adsorption onto the bacterial surface. At the same time, its amphiphilic structure enables adsorption on metal surfaces for corrosion inhibition, while its Gemini structure facilitates foaming. The surfactant exhibits self-assembly into micelles as the hydrophobic carbon chain length increases, displaying a low CMC and high surface activity.

The bactericidal effects are achieved by adsorption on the bacterial surface through the positively charged hydrophilic group. This surfactant has a long-lasting antibacterial effect, and harsh conditioning can assist in maintaining its bactericidal effect under acidic, alkaline, and high-temperature conditions. This efficacy is attributed to environmental advantages such as the complete ionization of H+ and alkaline ions, as well as rapid diffusion at elevated temperatures. The temperature variations influence the desorption of surfactant, and the aggregation and association of these molecules can impact the distribution and adsorption behavior, consequently diminishing their corrosion-inhibiting efficacy.

The surfactant exhibits favorable resistance to elevated temperatures and salinity levels due to its molecular composition. Specifically, it comprises a minimum of double hydrophobic chains and hydrophilic heads. This structural arrangement enhances the surfactant’s resilience to damage in high-temperature and saltwater environments, thereby preserving its stability. Moreover, the weakened interaction between hydrophilic head mitigates the likelihood of aggregation or precipitation under conditions of elevated temperature and in saline solutions.

Data availability

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper.

References

Li, J., Wen, M., Yang, J., Liu, J. & He, Z. Development and characterization of thermo-sensitive biomass-based smart foam drainage gas recovery treatment agent. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 230, 212263 (2023).

Liao, K., Qin, M., He, G., Yang, N. & Zhang, S. Study on corrosion mechanism and the risk of the shale gas gathering pipelines. Eng. Fail. Anal. 128, 105622 (2021).

Lai, R. et al. Bio-competitive exclusion of sulfate-reducing bacteria and its anticorrosion property. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 194, 107480 (2020).

Shaban, M. M. et al. Anti-corrosion, antiscalant and anti-microbial performance of some synthesized trimeric cationic imidazolium salts in oilfield applications. J. Mol. Liq. 351, 118610 (2022).

Kong, L., Zhao, W., Xuan, D., Wang, X. & Liu, Y. Application potential of alkali-activated concrete for antimicrobial induced corrosion: A review. Constr. Build. Mater. 317, 126169 (2022).

Zhang, Z. et al. Competition and cooperation of sulfate reducing bacteria and five other bacteria during oil production. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 203, 108688 (2021).

Tan, W., Li, Q., Dong, F., Chen, Q. & Guo, Z. Preparation and characterization of novel cationic chitosan derivatives bearing quaternary ammonium and phosphonium salts and assessment of their antifungal properties. Molecules 22 (9), 1438 (2017).

Paluch, E., Piecuch, A., Obłąk, E. & Wilk, K. A. Antifungal activity of newly synthesized chemodegradable dicephalic-type cationic surfactants. Colloids Surf. B 164, 34–41 (2018).

Guo, H. et al. Construction of stable magnetic vinylene-linked covalent organic frameworks for efficient extraction of benzimidazole fungicides. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 15(11), 14777–14787 (2023).

Li, F., Good, S., Tulchinsky, M. L. & Whiteker, G. T. Efficient stereoselective synthesis of a key chiral aldehyde intermediate in the synthesis of picolinamide fungicides. Org. Process Res. Dev. 23(10), 2253–2260 (2019).

Wang, Q., Wu, Y., Guo, W., Zhang, F. & Zhang, F. A magnetic covalent organic framework as selective adsorbent for preconcentration of multi strobilurin fungicides in foods. Food Chem. 392, 133190 (2022).

Mei, Q. X. et al. Surface properties and phase behavior of gemini/conventional surfactant mixtures based on multiple quaternary ammonium salts. J. Mol. Liq. 281, 506–516 (2019).

Zheng, T. et al. Synergistic corrosion inhibition effects of quaternary ammonium salt cationic surfactants and thiourea on Q235 steel in sulfuric acid: Experimental and theoretical research. Corros. Sci. 199, 110199 (2022).

Jin, F. Y., Yang, L. Y., Li, X., Song, S. Y. & Du, D. J. Migration and plugging characteristics of polymer microsphere and EOR potential in produced-water reinjection of offshore heavy oil reservoirs. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 172, 291–301 (2021).

Wang, Y. et al. The Effect and Mechanism of a Microbial Agent used for Corrosion Control in Circulating Cooling Water (Environmental Science: Water Research & Technology, 2024).

Xiong, C. et al. Nanoparticle foaming agents for major gas fields in China. Pet. Explor. Dev. 46(5), 1022–1030 (2019).

Chauhan, S., Kaur, M., Rana, D. S. & Chauhan, M. S. Volumetric analysis of structural changes of cationic micelles in the presence of quaternary ammonium salts. J. Chem. Eng. Data. 61(11), 3770–3778 (2016).

Kawai, R., Yada, S. & Yoshimura, T. Adsorption and aggregation behavior of mixtures of quaternary-ammonium-salt-type amphiphilic compounds with fluorinated counterions and surfactants. Langmuir 37(38), 11330–11337 (2021).

Chang, H. et al. Equilibrium and dynamic surface tension properties of Gemini quaternary ammonium salt surfactants with hydroxyl. Colloids Surf. A 500, 230–238 (2016).

Zhang, Q. et al. Surface tension and aggregation properties of novel cationic gemini surfactants with diethylammonium headgroups and a diamido spacer. Langmuir 28(33), 11979–11987 (2012).

Tavano, L. et al. Role of aggregate size in the hemolytic and antimicrobial activity of colloidal solutions based on single and gemini surfactants from arginine. Soft Matter 9(1), 306–319 (2013).

Cuenca, V. E., Falcone, R. D., Silber, J. J. & Correa, N. M. How the type of cosurfactant impacts strongly on the size and interfacial composition in gemini 12-2-12 RMs explored by DLS, SLS, and FTIR techniques. J. Phys. Chem. B 120(3), 467–476 (2016).

Hao, J., Qin, T., Zhang, Y., Li, Y. & Zhang, Y. Synthesis, surface properties and antimicrobial performance of novel gemini pyridinium surfactants. Colloids Surf. B 181, 814–821 (2019).

Ahmady, A. R. et al. Cationic gemini surfactant properties, its potential as a promising bioapplication candidate, and strategies for improving its biocompatibility: A review. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 299, 102581 (2022).

Sharma, R., Kamal, A., Abdinejad, M., Mahajan, R. K. & Kraatz, H. B. Advances in the synthesis, molecular architectures and potential applications of gemini surfactants. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 248, 35–68 (2017).

Heakal, F. E. T. & Elkholy, A. E. Gemini surfactants as corrosion inhibitors for carbon steel. J. Mol. Liq. 230, 395–407 (2017).

Shukla, D. & Tyagi, V. K. Cationic gemini surfactants: A review. J. Oleo Sci. 55(8), 381–390 (2006).

Kamboj, R., Singh, S., Bhadani, A., Kataria, H. & Kaur, G. Gemini imidazolium surfactants: Synthesis and their biophysiochemical study. Langmuir 28(33), 11969–11978 (2012).

Gu, Y. et al. Preparation and performance evaluation of sulfate-quaternary ammonium Gemini surfactant. J. Mol. Liq. 343, 117665 (2021).

Zhao, T. et al. Synthesis and oil displacement performance evaluation of cation-nonionic gemini surfactant. Colloids Surf. A 647, 129106 (2022).

Feng, J. et al. Study on the structure-activity relationship between the molecular structure of sulfate gemini surfactant and surface activity, thermodynamic properties and foam properties. Chem. Eng. Sci. 245, 116857 (2021).

Funding

This study received financial support from the China National Petroleum Corporation’s Applied Science and Technology Special Project (2023ZZ21), Postdoctoral Research Program of PetroChina Southwest Oil and Gas Field Company (20230303-18).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Jia Li: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing - Original Draft, Funding acquisition. Ming Wen: Writing – review & editing. Zeyin Jiang: Writing – review & editing. Shangjun Gao: Writing – review & editing. Xiao Xiao: Investigation. Chao Xiang: Data Curation. Ji Tao: Investigation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, J., Wen, M., Jiang, Z. et al. Formulation and characterization of surfactants with antibacterial and corrosion-inhibiting properties for enhancing shale gas drainage and production. Sci Rep 15, 2376 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87010-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87010-x

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Plant leaf extracts as green corrosion inhibitors of steel in acidic and seawater environments: a review

Environmental Science and Pollution Research (2025)