Abstract

Given the suboptimal physical properties and distinctive geological conditions of deep coalbed methane reservoirs, any reservoir damage that occurs becomes irreversible. Consequently, the protection of these deep coalbed methane reservoirs is of paramount importance. This study employs experimental techniques such as scanning electron microscopy, X-ray diffraction, and micro-CT imaging to conduct a comprehensive analysis of the pore structure, mineral composition, fluid characteristics, and wettability of coal seams 3# and 15# in the northern Qinshui Basin of China. The objective is to elucidate the types of reservoir damage induced by fracturing fluid intrusion along with potential contributing factors. This research is critical for ensuring safe drilling practices, effective gas injection, and efficient development strategies for coalbed methane reservoirs. The findings indicate that the mineral composition of the coal rock consists of 18.52% clay minerals, 34% quartz, and 8.98% calcite. Furthermore, hydrophilicity and natural fractures within the coal rock may lead to water-sensitivity, velocity- sensitivity, alkali- sensitivity, and acid- sensitivity damages to the coalbed methane reservoir. There exists good compatibility between fracturing fluids and both coal rock as well as formation water. The fine particles generated from hydraulic fracturing are prone to transport through the coal seam while obstructing pore throats. Thus exhibiting pronounced velocity sensitivity characteristics in this reservoir type. Coal rock demonstrates pronounced stress sensitivity. As the effective stress escalates from 2 MPa to 10 MPa, there is a marked decrease in the permeability of coal rock. With increasing effective stress, the pore structure and natural fractures within the coal rock are compressed more tightly, resulting in a diminished permeability of the coal rock. When exposed to fracturing fluid saturation, not only does the volume of these particles expand but they can also cause blockages that result in up to a 60% reduction in fracture flow capacity. These insights are vital for optimizing fracturing designs aimed at protecting reservoir integrity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Coalbed methane, also known as coal seam gas, is an unconventional form of natural gas that is formed and exists within coal seams. The majority of coalbed methane (70% ~ 95%) is adsorbed onto the inner surface of the pore spaces in the coal rock, with a small amount being free in fractures and other pores, and a minor portion dissolved in the water present in the coal bed1,2,3. As a novel type of clean unconventional natural gas, its development and utilization not only yield direct economic benefits but also play a crucial role in disaster reduction, atmospheric environment protection, and improvement of energy consumption structure. Coalbed methane reservoirs in China generally exhibit characteristics such as low porosity, low permeability, low pressure conditions, high gas recovery rates, and strong heterogeneity4,5,6,7. Additionally, due to their unique occurrence state and production mechanism considerations must be given to their low production efficiency and distinctive late mining characteristics when compared to conventional tight oil and gas reservoirs. Therefore, it is essential to thoroughly understand the physical properties, petrographic features, wettability, and potential damage factors of these reservoirs before exploring mechanisms for increased production efficiency or transformation8,9,10,11,12,13.

The characteristics of the pore structure of a coal seam determine the presence and movement of pore fluids. A coal reservoir is a dual-pore medium, consisting of matrix pores and cleavage fractures. Unlike typical dual-pore gas reservoirs, cleavages in coalbed methane reservoirs divide the coal into multiple matrix blocks that contain numerous micro pores, which serve as the primary space for gas storage with low permeability. On the other hand, cleavages form a secondary pore system that plays a significant role in fluid (gas and water) flow within the coal seam. Therefore, the structure and morphology of pores and cracks in coal rocks greatly influence gas accumulation potential and migration ability within the coal seam. Under various genetic types’ control, matrix pores in coal rocks exhibit complex morphologies affected by several internal factors such as volume, surface area, size distribution, and effective space size14,15,16. In comparison to sandstone and carbonate reservoirs, coal reservoirs generally demonstrate more intricate pore structures, possess enhanced adsorption capacities; however, they exhibit lower permeability, fragile mechanical properties, and a tendency to collapse in the vicinity of the wellbore. Gas recovery primarily occurs through adsorption at microscopic levels or small sizes during drilling operations on coal rocks17,18,19. This process weakens regional mechanical strength while exacerbating instability issues thereby affecting drilling engineering safety and efficiency. During drainage compression when pressure drops occur, effective stress increases leading to compression of micro-cracks resulting in decreased permeability. However, it also alleviates constraints imposed by capillary forces causing capillaries to contract/distort thus increasing fracture numbers ultimately enhancing reservoir permeability.

Compared to shallow coal seams, deep coal seam reservoirs exhibit poor physical property characteristics and undergo changing mining conditions, making their development more challenging. The existing production improvement technology faces challenges in terms of applicability and compatibility due to the unique geological conditions associated with deep coalbed methane development. Additionally, the need for protecting deep coal seam reservoirs becomes more prominent. Among various production improvement measures, commonly used active water fracturing technology may lead to filtration loss and blockage of proppant filling belt due to the vulnerability of deep coal reservoirs20,21. Foam fracturing fluid offers advantages such as minimal filtration loss, high sand carrying capacity, and good flowback ability, making it suitable for fracturing deep coalbed methane wells22,23. However, current foam fracturing fluids primarily composed of polymer thickening base liquid encounter difficulties in breaking down glue and suffer from polymer adsorption issues that can damage the coal seam. The serious water lock damage caused by filtrate from working fluid significantly reduces gas phase permeability within the reservoir. Therefore, conducting a comprehensive analysis of both pore structure in coals and rocks as well as potential damage factors affecting the reservoir is crucial for ensuring safe drilling operations, efficient gas injection processes, and effective development of coalbed methane24,25,26,27.

The engineering geological characteristics of coal mineral composition, wettability, and formation temperature and pressure conditions are analyzed in this paper using experimental methods such as scanning electron microscopy, X-ray diffraction, micro-CT, and wettability measurement. The potential damage factors of the coal reservoir are clarified, and the compatibility of conventional fracturing fluids is evaluated. Additionally, the impact of coal powder on the conductivity of supporting fractures is also discussed. These findings provide valuable insights for optimizing coalbed methane (CBM) fracturing design to protect the reservoir, considering both the potential damage factors and the compatibility of fracturing fluids. By taking these factors into account, the risk of reservoir damage can be minimized, ensuring safe and efficient drilling and hydraulic fracturing operations, as well as the effective development of coalbed methane resources.

The coal quality and mineral characteristics of coal rocks

Block geological background

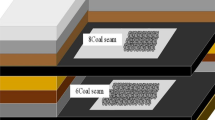

The research area is situated within the Shanxi formation of the Permian system in the Qinshui basin, China. The formation comprises 1–4 coal seams, with two economically exploitable seams: the 3# coal seam and the 15# coal seam, totaling a thickness of 10.70 m. Based on test results, the desorbed gas content of dry ash-free basis for the 3# coal seam generally ranges from 9.0 m3/t to 21.3 m3/t, while for the 15# coal seam it typically falls between 10.8 m3/t and 22.5 m3/t. Overall, the gas content of the 15# coal seam exceeds that of the 3# coal seam. The porosity of 3# coal seam ranges from 3.95 to 5.96%, while the porosity of 15# coal seam ranges from 5.1 to 5.92%, based on statistical analysis of core data. The measured permeability indicates that the permeability of 3# coal seam is (0.97 ~ 2.07) × 10−3µm2, whereas the measured permeability of 15# coal seam, due to its greater depth compared to 3# coal seam, is slightly lower, ranging (0.68 ~ 1.76) × 10−3µm2. Based on the injection/drawdown test data from the parameter wells in the study area, it is indicated that the pressure of 3# coal seam ranges from 3.76 to 5.94 MPa, with a pressure coefficient of 0.693–0.808. The pressure of 15# coal seam ranges from 4.40 to 6.74 MPa, with a pressure coefficient of 0.703–0.828, both indicating low-pressure reservoirs. Additionally, the geothermal gradient of the reservoir is approximately 1.8–2.2 °C/100 m.

Based on the in-situ stress data from the parameter wells in this area, it is determined that the minimum horizontal stress (i.e. confining pressure) of 3# coal seam ranges from 8.154 to 11.184 MPa, with an average of 9.869 MPa, and a stress gradient of 0.0029 to 0.0035 MPa/m. The minimum horizontal stress of 15# coal seam ranges from 10.037 to 15.208 MPa, with an average of 12.526 MPa, and a stress gradient of 0.0036 to 0.0057 MPa/m.

Coal quality analysis

(1) Macroscopic coal rock type and microscopic composition.

The coal rock type is dull coal-semi-dull coal, with a composition mainly consisting of dark coal, followed by light coal. Additionally, there is a small amount of linear-thin strip-shaped vitrinite, and locally visible thin layers of silk carbon (Fig. 1). The microscopic coal rock composition contains 52.76% vitrinite and 47.24% inertinite. The organic component accounts for 74.37%, and the organic component is mainly clay, accounting for 12.83%, and the contents of silicon oxide, sulfide and carbonate are 4.12%, 3.85% and 4.83%, respectively.

(2) Degree of coal metamorphism.

The coal has a high degree of metamorphism and has reached the stage of anthracite. The average reflectance of coal seam is 3.67%, and the metamorphic stage is all high - grade anthracite I.

(3) coal quality characteristics.

The water content of coal rock ranges from 0.52 to 1.71%, with an average of 0.98%. the ash content ranges from 17.73 to 63.15%, with an average of 34.27%. the volatile matter content ranges from 4.62 to 36.32%, with an average of 6.26%. the average total sulfur content is 1.18%, belonging to low - sulfur coal. the average carbon content is 89.35%. the true density is about 1.82 g/cm3, and the apparent density is about 1.74 g/cm3.

Mineral characteristics

The organic component of coal is referred to as the main body, while the inorganic mineral composition significantly influences reservoir damage and protection. Sensitive minerals can be categorized into four groups based on their propensity for reacting with fluids, leading to reservoir damage (Table 1).

The analysis of rock mineral composition can be divided into whole rock analysis and clay mineral analysis, both of which are determined through X-ray diffraction. Each crystalline substance, including crystalline minerals, possesses a unique chemical composition and crystal structure. By examining the behavior of various minerals in rocks at different diffraction angles and peak intensities on the X-ray diffraction spectrum, it is possible to accurately and rapidly determine the composition of diverse crystalline substances and minerals within rocks. Therefore, the application of X-ray diffraction technology allows for rapid and precise determination of the mineral composition in both whole rock samples and clay samples. By integrating this method with scanning electron microscopy analysis and conducting X-ray diffraction experiments, the type, occurrence, content, and distribution characteristics of sensitive minerals in rocks have been determined, a deeper understanding of the physical properties of the reservoir can be achieved, and potential damage types, degrees, and causes can be identified.

Whole rock analysis

According to the Stocks sedimentation theorem in hydrostatics, clay minerals with particle sizes less than 10 μm and 2 μm were extracted using water suspension separation or centrifugal separation methods. The clay mineral samples with particle sizes less than 10 μm were utilized to determine the total relative content in the original rock, while those with particle sizes less than 2 μm were used to determine the relative content of different types of clay minerals. Since each mineral crystal possesses a specific X - ray diffraction pattern, the intensity of characteristic peaks in the pattern is related to the mineral content in the sample. Therefore, through experiments, it can be determined that there is a positive correlation between a mineral’s content and its characteristic diffraction peak intensity - known as K value. When conducting quantitative analysis of X - ray diffraction using the “K value method,” one can calculate the mineral’s content by measuring its characteristic peak intensity in an unknown sample.

Where, \(\:{X}_{i}\)— the content of mineral i in the sample, %. \(\:{K}_{i}\)— Reference strength of mineral i (obtained from multiple determinations). \(\:{I}_{i}\)— the intensity of a diffraction peak of mineral i.\(\:{I}_{cor}\)— the intensity of the diffraction peak of corundum.

The analysis of clay minerals and non-clay minerals

(1) Determination of total amount of clay minerals.

According to the standard requirements, a rock sample weighing at least 50 g is initially measured, followed by undergoing oil washing, drying, crushing and grinding processes to ensure that all particle sizes are below 40 μm. Subsequently, all components with particle sizes less than 10 μm are extracted using the natural sedimentation method, and their percentage content is calculated based on the following formula.

Where, \(\:{X}_{10}\)— Amount of component in sample with particle size less than 10 μm, %. \(\:{W}_{10}\)— The mass of the component in the sample with a particle size of less than 10 μm, g. \(\:{W}_{T}\) — The sample quality, g.

The corundum was thoroughly mixed in a 1:1 ratio with the sample containing particles smaller than 10 μm before measuring the integral intensity of the selected diffraction peak. Subsequently, the K-value method (Eq. 2) was employed to determine the content of different non-clay minerals.

Therefore, the total amount of clay minerals can be obtained by calculating the sum of non-clay minerals with a particle size smaller than 10 μm, \(\:\sum\:{X}_{i}\).

Where, \(\:{X}_{TCCM}\) — content of clay minerals in coal, %.

(2) Determination of non-clay mineral content.

The determination of non-clay mineral content is directly conducted through the adiabatic method. Specifically, 1–2 g rock samples are taken and made into sheets according to relevant requirements. Then, the X - ray diffraction instrument is used to measure the integral intensity of selected diffraction peaks of various non-clay minerals. The percentage content of each non-clay mineral can be calculated using the adiabatic method with the following formula:

After conducting X - ray diffraction analysis, the whole-rock mineral composition of various well groups was determined. For specific test results, please refer to Fig. 2.

The results of inorganic whole-rock mineral analysis indicate that the coal rock contains 18.52% clay minerals, posing a high risk of sensitivity damage. Therefore, there is potential for sensitivity damage in the tested stratum. Among the non-clay minerals, quartz is one of the predominant components with the highest content, exceeding 34% even within the coal rock itself. Quartz microcrystals are particularly susceptible to alkali-sensitivity damage. Additionally, calcite constitutes 8.98% of the coal rock and can easily cause acid-sensitivity damage.

(3) Clay mineral composition analysis.

Utilizing the diffraction phenomenon of X-rays in clay mineral crystals, various types of clay minerals generate distinct diffraction patterns, thereby facilitating the determination of their mineral classification. N-plates are conventionally employed in X-ray diffraction analysis to identify the type and structure of clay minerals. Conversely, EG-plates represent another category of oriented thin sections derived from clay minerals that may have undergone specific treatments or preparations for more precise or condition-specific X-ray diffraction analyses. After the separation of clay minerals, the X’ PertMPD PRO powder X-ray diffractometer can be utilized for further determination of their types and contents. The qualitative analysis is employed to identify the types of clay minerals, while Table 2 provides a comprehensive overview of the X-ray diffraction identification characteristics commonly associated with these minerals. By employing an X-ray diffractometer, one can observe the spectral features specific to clay minerals, leading to analysis results indicating that illite, kaolinite, chlorite, illite-mullite mixed layer minerals and green mullite mixed layer minerals are predominantly present in the target area.

After conducting qualitative analysis, the X-ray diffraction analysis software can be utilized to perform peak separation of various clay minerals that have been identified in the sample. This allows for separate calculation of the areas of illite (It) and I/S interlayer minerals (I/S) peaks that overlap at l.00 nm. The clay mineral composition of different well reservoir rocks is tested using X-ray diffraction, with results displayed in Fig. 3.

After conducting X - ray diffraction analysis, it was determined that the rock sample does not contain smectite and green smectite. however, it exhibits a relatively high abundance of emeraldine smectite, ranging mostly between 55% and 76%. In terms of reservoir damage potential, this particular mineral type is susceptible to water sensitivity damage. Regarding clay minerals, chlorite, illite, and kaolinite are present in descending order of content. Additionally, with respect to clay minerals specifically, kaolinite primarily contributes to tach sensitivity damage. nevertheless, all clays and non-clay particles smaller than 37 μm can induce the velocity sensitivity damage of reservoir when they exist as bridging or pore-filling agents. It is also noteworthy that due to their elevated concentration levels, these minerals are prone to hydrochloric acid sensitivity damage. To summarize the findings from the X - ray diffraction analysis: the tested formation contains a substantial number of clays which may pose potential risks for sensitivity-related damages. Importantly though, it should be emphasized that while there is an absence of smectite and green smectite in the rock sample analyzed here. instead, there exists a significant quantity of emeraldine smectite – making this specific rock sample more susceptible to water sensitivity damage from a reservoir perspective.

Microscopic characteristics of coal pores

According to the test results of parameter well samples, the average porosity of coal rock is determined to be 4.42%. Injection/pressure drop tests were conducted on 16 gas wells in the study area, revealing that the overall permeability of the coal seam is relatively low, ranging (0.02 ~ 1.28) × 10−3µm2. Reservoir pore structure encompasses the geometric characteristics, size distribution, and interconnectivity of pores and throats within the reservoir. Microscopic research categories include analysis of reservoir pore structure, pore wall characteristics, and filling material properties. While macroscopic research categories encompass investigation into reservoir porosity, permeability, fluid saturation levels, and sensitivity.

(1) SEM analysis of microscopic pore structure of rock.

The scanning electron microscope (SEM) was developed in the 1960s and is commonly referred to as SEM. It utilizes a focused electron beam to scan the sample, thereby exciting specific physical signals that adjust the brightness of the image tube at corresponding positions during synchronous scanning, ultimately achieving imaging. As a type of microscope, SEM analysis provides visual information on the composition and distribution of filling minerals within pores, making it an essential tool for studying pore structure. In addition to offering insights into particle characteristics such as type, size, content, and symbiotic relationships within the pore system, SEM analysis also enables identification of clay mineral types and occurrences along with their respective contents while facilitating observation of pore morphology, size variations, and connectivity.

According to Fig. 4, the lithology demonstrates high density and is primarily composed of micropores and microfractures. Quartz and Emeraldine mixed layers are observed in the distribution across particle surfaces. The framework feldspar exhibits erosion stripes, while the quartz shows significant dissolution. The framework surface appears uneven with offsets from the Emeraldine mixed layers. Some areas show signs of pyrite spalling. Furthermore, localized pores (also known as biopores) have developed on the matrix surface, which are filled with various clay minerals, microcrystalline quartz, feldspar, calcite, etc. Overall, the lithology demonstrates favorable porosity characteristics. The lithology exhibits a highly dense composition primarily consisting of organic micropores along with localized fractures. On the framework surface, clay minerals and scattered microcrystalline quartz can be observed, while feldspar displays plate-like spalling patterns. The matrix surface appears relatively smooth with developed pores that are filled with clay minerals and quartz materials. Emeraldine mixed layers are distributed both inside and outside the cave area, occasionally containing oblate pyrite that leaves signs of spalling behind. Overall, the lithology exhibits commendable porosity characteristics.

(2) Micro CT analysis.

Using computed tomography (CT) technology, the internal structure of materials can be nondestructively imaged. Micro CT offers high resolution, enabling detailed investigation of porous material structures. Different materials exhibit varying X-ray transmission abilities. CT scans the non-uniform sample internally using X-rays and captures light intensity at different receiver positions. The resulting gray image of light intensity provides a projection of the sample (as shown below). By discretizing and reconstructing cross-sectional images at different angles but at the same height, a cross-sectional image at that specific height can be obtained. This cross-sectional image provides spatial gray values for each point, facilitating easy acquisition of sections parallel to the vertical direction (Z direction). In this experiment, the sample is rotated 360 ° with a projection image acquired every 0.9 °. Combining these projection images with relevant analysis software allows for the reconstruction of an uncompressed BMP format cross-sectional gray image file measuring 736 × 736 pixels square in size. Additionally, three-dimensional reconstruction and other processing can be performed using this cross-sectional image data. During the three-dimensional reconstruction process of the core, software aids in enhancing gray contrast to highlight bright matrix areas while filtering slightly dark pore areas to effectively reveal fracture characteristics. Figure 5 displays a partial view two-dimensional X-ray CT scan image of coal which demonstrates small fractures partially filled with minerals and well-developed cleavage.

The rock fissures in this region are well-developed, and the pore structure of coal reservoirs is favorable for the flow of coalbed methane. However, it should be noted that the discrepancy between solid particle intrusion and particle migration may result in reservoir damage caused by foreign solids.

Wettability characteristics of coal rock

The liquid on the surface of rocks exhibits automatic flow characteristics. Numerous scholars have undertaken comprehensive research and analysis regarding the contact angle and wetting characteristics of oil droplets and water droplets within oil and gas reservoirs. These investigations primarily concentrate on the physical properties, fluid interactions, and interfacial phenomena associated with various types of oil and gas reservoirs. Employing experimental techniques alongside numerical simulations, researchers have examined the factors influencing variations in contact angle, including temperature, pressure, liquid composition, and surface roughness28,29.

When the surface of reservoir rocks possesses oil absorption and drainage properties, it is not easily wetted by water, known as oil-wetting, with a contact angle greater than 90°. Conversely, when the surface of reservoir rocks demonstrates water absorption and drainage properties, it is readily wetted by water, referred to as hydrophilic behavior, with a contact angle less than 90°. If there is no significant mutual replacement between oil and water on the rock’s surface, it is considered neutral with a contact angle equal to 90 °. The wetting angle refers to the tangent angle formed at a certain point in the three-phase junction where the gas-liquid interface meets the solid-liquid interface after expansion and equilibrium are reached on an object’s surface. By measuring this wetting angle, one can determine whether the rock is hydrophilic or hydrophobic. Experimental methods include testing the wetting angle using distilled water and drying core samples after soaking them in fracturing fluid for four hours (Table 3).

Experimental observations have revealed that the coal sample demonstrates strong water wetting, characterized by a small wetting angle and correspondingly high capillary pressure. Capillary force serves as a crucial indicator for assessing the extent of water blockage in tight gas reservoirs, with greater capillary force indicating more severe damage. However, following fracturing fluid treatment, the coal sample’s wetting angle transitions to a flat state (i.e., reduced to 0°), displaying complete water-wetting characteristics and increased wettability. This trend may lead to an increase in capillary force, which is unfavorable for gas flow and more likely to cause water locking damage.

Properties of coal seam fluid

(1) Characteristics of coalbed methane components.

The methane gas component content ranges from 84.7 to 98.45%, with an average of 91.95%. The nitrogen gas content ranges from 1.28 to 14.79%, with an average of 7.42%. The carbon dioxide content ranges from 0.19 to 0.52%, with an average of 0.38%, and the heavy hydrocarbon gas content is negligible.

(2) Coal bed water quality.

The coal seam water in this area is mainly sodium sulfate water, indicating shallow water characteristics. The salinity is 2657.6 ~ 29347.2 mg/L, with an average of 12843.6 mg/L.

Temperature and pressure characteristics

The main coal seam in the target area is moderately buried, primarily at a shallow depth of 900 m. The measured reservoir temperature ranges from 18 to 45 °C, and the geothermal gradient mostly remains below 3 °C/100 m, predominantly distributed between 1.90 and 2.62 °C /100m. Based on the well test results of parametric wells in the area (Fig. 6), the coal reservoir pressure varies from 3.30 to 11.86 MPa, with each well exhibiting a pressure gradient ranging from 0.70 to 1.20 MPa/100 m within the normal pressure system range. The areas with steeper dip angles have higher pressures compared to those with gentler dip angles. The fracture pressure of the coal seam depends on its burial depth and mechanical properties of surrounding rocks. specifically, it ranges from 7.90 to 18.15 MPa for coal fractures, while wellhead fracture pressure gradients fall between 1.46 and 3.41 MPa/100 m. Closure pressures range from 7.21 to 17 0.24 MPa and increase proportionally with increasing dip angle.

Engineering factors of reservoir damage

Compatibility of fracturing fluid and formation fluid

Experimental liquid

Upon introduction into the formation, the fracturing fluid will come into contact with and blend with the formation fluid. Due to disparities in ion types and concentrations between the two fluids, precipitation may occur upon mixing. Therefore, it is crucial to combine the fracturing fluid with the formation fluid and observe any alterations or occurrence of precipitation within the mixed solution. The formula for fracturing fluid used corresponds to that utilized on-site.

1% KCl + 0.5% Coal powder dispersant + 0.05% Bactericidal agent + Water.

Experimental procedure

Firstly, the formation fluid should be filtered to remove any solid impurities. Next, combine 50 mL of the filtrate from the formation fluid with 50 mL of fracturing fluid (prepared using distilled water) and allow it to stand for a duration of 1 h in order to observe the mixture. Subsequently, introduce 50 mL of tap water and leave it for an additional hour to observe the resulting mixture.

Experimental results and analysis

After analyzing Table 4, it was observed that, except for No. 5 and No. 8, the filtrates of formation fluids appeared as colorless and clear liquids. The filtrate from No. 8 exhibited a yellow hue while remaining clear, whereas the filtrate from No. 5 appeared as a slightly transparent milky yellow microemulsion liquid. Apart from No. 5, there were no observable changes in the formation fluids after adding fracturing fluid and tap water; no precipitation occurred either. However, after standing for 1 h, the filtrate from No. 5 showed a slight yellowing but still did not precipitate. Upon addition of tap water and subsequent one-hour standing time, further discoloration occurred along with decreased transparency in this particular sample’s formation fluid filtrate. This phenomenon may be attributed to the oxidation of Fe2+ into Fe3+, which could have been caused by the presence of oxygen in the air or tap water sources, respectively. Furthermore, it is worth noting that although no precipitation was observed within the mixture itself, its transparency diminished while becoming more turbid - indicating a tendency towards precipitation albeit without actual occurrence. In summary, both fracturing fluid and tap water demonstrated good compatibility with the formation fluid.

Compatibility between fracturing fluid and formation rocks

Experiment evaluation of reservoir sensitivity

(1) Principles of experimental evaluation.

In this experiment, the liquid phase was utilized as the fluid medium. Following Darcy’s law, we introduced various liquids associated with formation damage or altered seepage conditions (such as flow velocity and net confining pressure) to measure the permeability of the rock sample and assess the extent of damage caused by critical parameters, experimental liquids, and seepage conditions on its permeability. Within rocks, liquids adhere to Darcy’s law for their flow behavior. The subsequent formula can be employed to calculate the permeability of the rock sample.

Where, \(\:{K}_{1}\)— The liquid permeability of rocks, × 10−3µm2. \(\:\mu\:\)—Fluid viscosity, mPa·s. \(\:L\)— Rock sample length, cm. \(\:A\)— Sample cross-sectional area, cm2. \(\:\varDelta\:p\)— The pressure difference at both ends of the rock sample, MPa. \(\:Q\)— The volume of fluid passing through a rock sample per unit time, cm3/s.

(2) Preparation of experimental rock cores.

The standard core drilling direction should align consistently with the flow direction of reservoir liquids to ensure the preservation of mineral composition and pore structure in the core. The end face and cylindrical surface of the sample must be flat, with the end face perpendicular to the cylindrical surface, free from any missing angles or structural defects. The sample diameter is 2.54 cm (1 inch), while its length ranges from 3.0 to 3.5 cm. Prior to conducting experiments, it is essential to thoroughly clean all original fluids within the sample. In case of an unknown composition, a mixture of alcohol and benzene should be employed for cleaning purposes. When dealing with local formation water salinity exceeding 20,000 mg/L, desalination using methanol reagent becomes necessary. To maintain unchanged properties of clay and gypsum in the sample, drying temperature should not exceed 60 °C, ensuring each sample is dried until reaching constant weight for no less than 48 h.

(3) Preparation of experimental fluids.

According to the actual circumstances, a simulated experimental brine was prepared. Based on geological data, the coal bed water produced in this area is classified as sodium sulfate type, indicating its shallow water characteristics. The salinity ranges from 2657.6 to 29347.2 mg/L, with an average value of 12843.6 mg/L. To ensure compliance with standard requirements for the quality of the experimental fluid, it should be allowed to settle for at least one hour and subsequently filtered through a 0.20-micron filter prior to testing.

(4) Experimental evaluation of coal rock velocity sensitivity damage.

The purpose of the velocity sensitivity evaluation experiment is to explore the relationship between formation permeability and fluid velocity variation, and determine the critical velocity Vc or critical flow Qc value, so as to provide a scientific basis for selecting appropriate flow velocity in the laboratory and on the site.

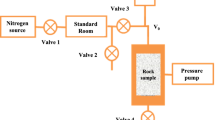

Constitute 1.25% Na2SO4 solution to simulate formation water. Evacuate and saturate the rock sample for more than 24 h. Put the saturated rock sample into a core holder and gradually increase the confining pressure to 4.0 MPa. Test the rock permeability value at flow rates of 0.1 mL/min, 0.25 mL/min, 0.5 mL/min, 0.75 mL/min, 1.0 mL/min, 1.5 mL/min, 2.0 mL/min, 3.0 mL/min, 4.0 mL/min, 5.0 mL/min and 6.0 mL/min.

The test fluid was simulated formation water (1.25% Na2SO4 solution) with a net confining pressure of 4.0 MPa.

The flow velocity sensitivity injury rate can be calculated based on Eq. 7. For the relevant evaluation indexes of sensitivity, please refer to Table 5 below.

Where, \(\:\overline{{K}_{n}}\)—Permeability corresponding to the point where the permeability changes the most at different flow rates, × 10−3µm2. Ki—Permeability at minimum flow rate, × 10−3µm2.

The critical flow velocity (VC) refers to the flow velocity at the preceding point where the rate of change in rock permeability (DVm) exceeds 20%.

(5) Experimental results and analysis.

The coal and rock samples were subjected to a velocity-sensitivity evaluation, resulting in the determination of the permeability ratio and injection velocity relationship curve for both samples (Fig. 7).

The velocity-sensitivity damage rate of rock sample 1 and sample 2 are calculated, and the results show that they belong to strong velocity sensitivity.

DV1=99.46%, VC1=0.2 mL/min.

DV2=97.61%, VC2=0.2 mL/min.

Based on the experimental data acquired from velocimetry of two coal rock cores, it can be inferred that the coal rock reservoir demonstrates significant damage in terms of velocity measurements. This damage is characterized by alterations in flow dynamics and potential disruptions to the structural integrity of the reservoir. However, as the flow velocity of formation water increases, rather than decreasing, permeability exhibits an unexpected enhancement. This phenomenon indicates a complex interaction between fluid dynamics and geological properties within the reservoir. The loss of fine coal particles was observed under conditions of high flow velocity, likely attributed to particle shedding and migration processes occurring at elevated velocities. These fine particles are sufficiently small to escape their original locations but not large enough to effectively obstruct seepage channels; instead, they contribute to enhancing overall permeability by creating additional pathways for fluid movement. Consequently, this interplay between particle behavior and fluid flow may have substantial implications for resource extraction strategies and reservoir management practices.

Influence of fracturing fluid on coal powder volume

(1) Experimental steps and evaluation methods.

Based on X-ray diffraction analysis of rock minerals, coal demonstrates potential water sensitivity. To evaluate the compatibility between fracturing fluid and coal, the impact of fracturing fluid on coal powder volume can be measured. This test method is akin to the swelling rate test for clay stabilizers. Due to the higher density of coal powder compared to bentonite, 1.0 g instead of 0.5 g was used in this experiment. The experimental procedure involves adding 10.0 mL each of kerosene, clear water, and a formulated fracturing fluid (consisting of 1% KCl, 0.5% coal powder dispersant, 0.05% bactericide and water) into a centrifuge tube with weighed coal powder (1.0 g). After shaking and allowing it to settle for 2 h, the tube is centrifuged at a velocity of 1500 r/min for 15 min before reading the volume of immersed coal powder as V1 in fracturing fluid or V0 in kerosene as original volume. A new indicator called “swelling rate” is defined by comparing these volumes.

(2) Experimental results and analysis.

Upon analyzing the data presented in Table 6, it is evident that following a 2-hour immersion in fracturing fluid, the average swelling volume of coal powder measures 0.24 mL, with a corresponding swelling rate reaching 9.83%. This notable increase indicates that the interaction between coal powder and fracturing fluid results in significant volumetric changes. It is clearly observable that within this context, volumetric expansion occurs upon contact between coal powder and fracturing fluid, suggesting a complex relationship between the chemical composition of the fluid and the physical properties of the coal material. Furthermore, this phenomenon may potentially lead to reductions in pore space and fracture networks due to the presence of nano-scale pores within both coal and rock formations. The observed swelling behavior could result in alterations to permeability characteristics as well as modifications to flow pathways within these geological structures. Consequently, such changes may adversely affect the integrity of the rock stratum by compromising its mechanical stability and overall performance during extraction processes.

Coal rock adsorption damage experiment

Experimental methods

The coal sample is initially vacuum-drained to saturate the subsurface water and determine its permeability. Subsequently, the test drilling fluid filtrate is injected into the coal sample in reverse direction until 10 PV (Pore volume, that means ten times the volume of liquid in the pore space), and the permeability of the coal sample is monitored. After sealing for several hours, the subsurface water is then injected into the coal sample in forward direction until stabilization, and the permeability of the coal sample is determined again. The damage rate of coal permeability serves as the evaluation parameter. It can be calculated according to the following formula.

Where, \(\:S{I}_{p}\)- The damage rate of core matrix permeability, %. \(\:{K}_{1}\)- The benchmark permeability of the rock core, × 10−3µm2. \(\:{K}_{2}\)- Core permeability after fracturing fluid damage, × 10−3µm2.

The initial permeability of a coal sample is determined by injecting groundwater into the formation in the forward direction, while the post-damage value is obtained by injecting fracturing fluid filtrate in the reverse direction and then injecting groundwater in the forward direction after 10 PV of injection.

Experimental results and analysis

In the evaluation test assessing permeability damage to coal samples induced by fracturing fluid filtrate, the permeability change curve over time was observed in Table 7. The test results indicate that the damage to coal sample permeability caused by the fracturing fluid system is significantly greater than that associated with active water fracturing fluid. This discrepancy underscores the varying impacts of different fluid compositions on coal integrity. Specifically, the adsorption effect of the fracturing fluid system plays a critical role in impairing coal sample permeability, resulting in an average damage rate of 40.62% for guan gum-based fracturing fluid and 22.51% for active water fracturing fluid. Such differences can be attributed to factors including chemical interactions among components within each type of fluid and their respective capacities to penetrate and modify pore structures within the coal matrix. Furthermore, these findings emphasize the necessity of selecting appropriate fracturing fluids based on their potential effects on reservoir properties during extraction processes, as excessive loss of permeability could negatively impact hydrocarbon recovery efficiency.

Experimental evaluation of coal rock stress sensitivity

Experimental methods

As oil and gas reserves undergo continuous development, the pore pressure within the reservoir gradually declines, resulting in an increase in the effective stress on the rock framework. Consequently, the pore structure of the rock will change correspondingly due to variations in effective stress, a characteristic referred to as rock stress sensitivity30. Due to stress-sensitivity damage in the rock formations, the permeability of oil and gas reservoirs is reduced, leading to a decrease in the productivity of oil and gas wells.

The damage rate of permeability caused by rock stress sensitivity can be calculated using the following formula.

Where, \(\:{D}_{k2}\) is the maximum damage to permeability caused by the stress increasing to its peak during the process. \(\:{K}_{1}\)- The permeability of the rock sample corresponding to the first stress point, × 10−3µm2. \(\:{K{\prime\:}}_{min}\) is the minimum permeability of the rock sample after reaching the critical stress, × 10−3µm2.

Experimental results and analysis

Table 8 shows that the permeability ratio of the fractured coal sample changes in a specific trend with the change of effective stress during the loading and unloading process. It can be observed that the coal sample’s permeability decreases the most when the effective stress increases from 3 to 5 MPa. However, the permeability of the coal sample after fracturing fluid damage is difficult to recover during the unloading process as the effective stress decreases. Therefore, it can be inferred that the coal sample undergoes stress-sensitivity damage after experiencing fracturing fluid damage, and its permeability is difficult to recover.

The coal rock is composed of a network of large molecules with strong connectivity and disconnected large molecules, resulting in a higher capacity to adsorb various fluids and gases compared to conventional reservoir rocks15. The adsorption of liquid induces swelling in the coal rock matrix, given that the porosity of coal seam fractures is merely 1–2%7. Even minimal swelling caused by fracturing fluid can significantly diminish both fracture porosity and permeability within the coal seam. This reduction in permeability has substantial implications for hydrocarbon extraction efficiency, as it directly influences the flow pathways within the reservoir. Moreover, the irreversible swelling of the matrix resulting from fracturing fluid adsorption renders it nearly impossible to eliminate the adsorbed fluid or mitigate damage to coal seam permeability through conventional pressure drop methods. Additionally, chemical additives present in fracturing fluids engage in complex physical-chemical coupled reactions with the coal sample upon contact. These interactions not only lead to decreased permeability but also compromise the mechanical properties of the coal structure itself. Alterations in mechanical integrity may result in increased brittleness or heightened susceptibility to further damage under stress conditions. Consequently, this phenomenon significantly contributes to an increase in stress sensitivity within these formations.

The coal rock exhibits low mechanical strength and extensive microfractures, rendering it more susceptible to stress variations compared to other rock formations. During hydraulic fracturing operations, there is a possibility of the fracturing fluid infiltrating the near-well zone, thereby exacerbating the stress sensitivity of the reservoir.

An experimental investigation into the stress sensitivity of fractured coal rock samples treated with conventional fracturing fluid revealed that such treatment enhanced the stress sensitivity of the coal sample (Fig. 8). This enhancement indicates a significant alteration in the mechanical behavior of the coal under varying stress conditions, which is critical for understanding its performance during hydrocarbon extraction processes. Throughout the closed-stress loading process, a distinct trend was observed in both permeability and effective stress response of the fractured coal sample. Specifically, there was a notable decrease in permeability as effective stress increased from 2 to 10 MPa. This reduction can be attributed to several factors, including changes in pore structure and matrix swelling induced by fluid adsorption. As effective stress rises, it compresses the fractures within the coal matrix more tightly, thereby reducing available flow pathways for fluids.

Influence of coal powder on fracture conductivity

The brittle nature of coal makes coal reservoirs prone to collapse and the generation of coal powder and other particles during migration. The pressure differential generated during drainage and workover operations can stimulate the formation of coal powder within the coal bed. In CBM reservoir, dust generation from the coal bed is inevitable. During the stable drainage stage and declining production phase, as water output gradually decreases, hydrodynamic forces diminish, making it challenging to discharge the coal powder from the channel into the wellbore. The deposition of coal powder in the channel will impact fracture conductivity, subsequently affecting CBM desorption and seepage.

(1) Experimental principle

Where, Ko—Permeability of fracture, µm2. Qo—The flow rate in the fracture, cm3/s. µ—Viscosity of experimental gas, mPa·s. L—Length of test segment, cm. W—Fill layer width, cm. Wf —Filling layer thickness, cm. P1—Pressure at the inlet end, kPa. P2 —Pressure at the outlet end, kPa.

The permeability and conductivity of the bracing fracture are calculated as follows:

Where, \(\:{F}_{RCD}\)—Fracture conductivity, µm2·cm. \(\:{W}_{f}\)—Filling fracture width, cm. Q—The flow of fluid in the fracture, cm3/min.

(2) Experimental conditions.

The experiment utilized 35.64 g of quartz sand proppant and a sand concentration of 5 kg/m2 as the medium, with nitrogen serving as the testing medium. To investigate the impact of coal powder on fracture conductivity, we incorporated 20% coal powder into the proppant for testing purposes and compared its conductivity to that of the proppant without coal powder.

(3) Experimental Procedures.

Polish the apron and steel sheet. Clean the flow guide chamber thoroughly, replace the filter screen on the inner side of the flow guide chamber, and install it flush with the inner surface. Apply Vaseline to the upper and lower piston sleeves, then insert them vertically into the flow guide chamber. Place the lower steel plate in position, add and level out the weighed proppant. Securely position the upper steel plate using tape within the flow guide chamber. Finally, insert the upper piston vertically into place within the flow guide chamber.

(4) Analysis of experimental results.

As shown in Fig. 9, the conductivity test values of 20/40 mesh quartz sand (Its particle size is approximately 1 ~ 2 mm) without coal powder range from 78.3 µm2·cm to 3.92 µm2·cm, and the conductivity gradually decreases with the increase of closure pressure. However, after adding coal powder, the conductivity significantly decreases, fluctuating between 63.14 µm2·cm and 1.93 µm2·cm. Compared with the test without coal powder, the conductivity is reduced by about 40–55%. Therefore, it can be seen that coal powder blockage and migration has a certain impact on the conductivity. In the case of 70/140 mesh quartz sand (Its particle size is approximately 109 ~ 212 μm) without coal powder, the conductivity test values range from 20.17 µm2·cm to 1.95 µm2·cm, and the conductivity gradually decreases with the increase of closure pressure. However, after adding coal powder, the conductivity significantly decreases, fluctuating between 12.38 µm2·cm and 0.93 µm2·cm. Compared with the test without coal powder, the conductivity is reduced by about 40–60%. Therefore, it can be seen that coal powder blockage and migration reduces the fracture conductivity.

Conclusions

This study employed experimental techniques, including scanning electron microscopy, X-ray diffraction, and micro-computed tomography, to conduct a systematic and comprehensive analysis of the pore structure, mineral composition, fluid properties, and wettability of coal seams 3# and 15# in the northern region of the Qinshui Basin. The mineral composition analysis of the coal rock within the block reveals that the clay mineral content is 18.52%, while the quartz content reaches as high as 34% and calcite constitutes 8.98%. The coal rock demonstrates significant hydrophilicity and well-developed fractures, which present potential risks such as water sensitivity, velocity sensitivity, alkali sensitivity, and acid sensitivity regarding coalbed methane reservoir formation damage.

The coal-rock reservoirs exhibit significant velocity-sensitivity damage., and the intrusion of fracturing fluid further intensifies the reservoir’s sensitivity to stress. As effective stress escalates from 2 MPa to 10 MPa, the porous structure and natural fractures within the coal rock are compressed more tightly, leading to a marked reduction in permeability.

Fracturing fluids exhibit excellent compatibility with the fluids present in coal and rock reservoirs. Coal powder is readily transported within coal seams, while both coal and rock display pronounced characteristics of velocity sensitivity and stress sensitivity. Furthermore, exposure to fracturing fluids induces volume expansion in coal powder. However, potential plugging caused by the presence of coal powder may lead to a reduction in fracture conductivity by approximately 40–60%, significantly affecting proppant pack conductivity.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Altowilib, A., AlSaihati, A., Alhamood, H., Alafnan, S. & Alarifi, S. Reserves estimation for coalbed methane reservoirs: a review. Sustainability 12 (24), 10621 (2020).

Jia, Q., Liu, D., Cai, Y., Fang, X. & Li, L. Petrophysics characteristics of coalbed methane reservoir: a comprehensive review. Front. Earth Sci. 2020 Oct. 15:1–22 .

Li, L., Liu, D., Cai, Y., Wang, Y. & Jia, Q. Coal structure and its implications for coalbed methane exploitation: a review. Energy Fuels. 35 (1), 86–110 (2020).

Li, H., Lau, H. C. & Huang, S. China’s coalbed methane development: a review of the challenges and opportunities in subsurface and surface engineering. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 166, 621–635 (2018).

Carpenter, C. Coalbed methane development in China: challenges and opportunities. J. Petrol. Technol. 70 (07), 67–68 (2018).

Li, S. et al. A comprehensive review of deep coalbed methane and recent developments in China. Int. J. Coal Geol. 26, 104369 (2023 Sep).

Qin, Y. et al. Resources and geology of coalbed methane in China: a review. Coal Geol. China. 28, 247–282 (2020 Apr).

Pashin, J. C., Pradhan, S. P. & Vishal, V. Formation damage in coalbed methane recovery. In Formation Damage during Improved Oil Recovery 2018 Jan 1 (pp. 499–514 ). Gulf Professional Publishing.

Chen, Z., Khaja, N., Valencia, K. L. & Rahman, S. S. Formation damage induced by fracture fluids in coalbed methane reservoirs. In SPE Asia Pacific Oil and Gas Conference and Exhibition. Sep 11 (pp. SPE-101127). SPE. (2006).

YANG, H. L., WANG, W. Y. & TIAN, Z. L. Reservoir damage mechanism and protection measures for coal bed methane. J. China Coal Soc. 39 (1), 158–163 (2014).

Huang, W. et al. Damage mechanism and protection measures of a coalbed methane reservoir in the Zhengzhuang block. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 26, 683–694 (2015).

Lau, H. C., Li, H. & Huang, S. Challenges and opportunities of coalbed methane development in China. Energy Fuels. 31 (5), 4588–4602 (2017).

Akbari, S., Mahmood, S. M., Nasr, N. H., Al-Hajri, S. & Sabet, M. A critical review of concept and methods related to accessible pore volume during polymer-enhanced oil recovery. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 182, 106263 (2019).

Mohamed, T. & Mehana, M. Coalbed methane characterization and modeling: review and outlook. Energy sources, part A: recovery, utilization, and Environmental effects. Dec 5:1–23. (2020).

Wang, Z., Liu, S. & Qin, Y. Coal wettability in coalbed methane production: a critical review. Fuel 303, 121277 (2021).

Liu, D. et al. Experimental evaluation of working fluid damage to gas transport in a high-rank coalbed methane reservoir in the Qinshui basin, China. Acs Omega. 8 (15), 13733–13740 (2023).

CAI, J. H., Yuan, Y., WANG, J. J., LI, X. J. & CAO WJ. Experimental research on decreasing coalbed methane formation damage using micro-foam mud stabilized by nanoparticles. J. China Coal Soc. 38 (9), 1640–1645 (2013).

Wang, X., Hu, Q. & Li, Q. Investigation of the stress evolution under the effect of hydraulic fracturing in the application of coalbed methane recovery. Fuel 300, 120930 (2021).

He, J. et al. Formation damage mitigation mechanism for coalbed methane wells via refracturing with fuzzy-ball fluid as temporary blocking agents. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 90, 103956 (2021).

Huang, F., Dong, C., You, Z. & Shang, X. Detachment of coal fines deposited in proppant packs induced by single-phase water flow: theoretical and experimental analyses. Int. J. Coal Geol. 239, 103728 (2021).

Huang, F., Dong, C., Shang, X. & You, Z. Effects of proppant wettability and size on transport and retention of coal fines in saturated proppant packs: experimental and theoretical studies. Energy Fuels. 35 (15), 11976–11991 (2021).

Cai, J. et al. Decreasing coalbed methane formation damage using microfoamed drilling fluid stabilized by silica nanoparticles. Journal of Nanomaterials. ; 2016: 52-. (2016).

Huang, F., Kang, Y., You, L., Li, X. & You, Z. Massive fines detachment induced by moving gas-water interfaces during early stage two-phase flow in coalbed methane reservoirs. Fuel 222, 193–206 (2018).

HUANG, W. A. et al. Study on damage mechanism and protection drilling fluid for coalbed methane. J. China Coal Soc. 37 (10), 1717–1721 (2012).

Su, X., Wang, Q., Lin, H., Song, J. & Guo, H. A combined stimulation technology for coalbed methane wells: part 1. Theory and technology. Fuel 233, 592–603 (2018).

Goraya, N. S., Rajpoot, N. & Marriyappan Sivagnanam, B. Coal bed methane enhancement techniques: a review. ChemistrySelect 4 (12), 3585–3601 (2019).

Zhang, J. et al. Stimulation techniques of coalbed methane reservoirs. Geofluids. ; 2020: 1–23. (2020).

Sharifigaliuk, H., Mahmood, S. M., Rezaee, R. & Saeedi, A. Conventional methods for wettability determination of shales: a comprehensive review of challenges, lessons learned, and way forward. Mar. Pet. Geol. 133, 105288 (2021).

Khosravi, V. et al. A. O., New insights from nanoscale in-depth investigation into wettability modification in oil-wet porous media. Int. J. Comput. Mater. Sci. Eng., 2350045. (2023).

Yang, Y. et al. Influence of stress sensitivity on microscopic pore structure and fluid flow in porous media. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 36, 20–31 (2016).

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This study was supported by “The Ministry of Science and Technology of Sinopec Project: Automatic linkage control technology for the drilling overflow of the fractured gas reservoir, grant number P22117) and Key Technology of Volume Fracturing for Medium shallow Tight Sandstone Gas Reservoirs in Western Sichuan, grant number P22017”. The authors are grateful for the support of the National Natural Science Foundation of China. Thanks to reviewers and editors for their careful review of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Hongjian Wu and Xiangwei Kong wrote the main manuscript text and figures. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, H., Kong, X. Analysis of geological characteristics and potential factors of formation damage in coalbed methane reservoir in Northern Qinshui basin. Sci Rep 15, 3025 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87026-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87026-3