Abstract

Locking plates have a rapidly growing process especially in the past decades and results are satisfactory especially in the osteoporotic bones compared to non-locking compression plates. There are many forms of failure in the fracture fixation of locking plates, and screw pull-out is one of the main failure reasons. In this study, we aim to investigate pull-out failure in locking plates using locking spongious screws. The pull-out force of an FDA approved locking plate system (LPS) and anonymous locking plate using the single lead head locking spongious screw (LPuLSS) was evaluated in vitro on the PCF-15 and PCF-10 osteoporotic sawbone models. A total of 28 individual plate-bone models were tested and pull-out force was evaluated on a distraction machine. The moment of separation of the screws from the bone blocks was noted. In the first study using PCF15 bone model, in Group 1, the pull-out force has an average of 606.82 N. In Group 2, the pull-out force has an average of 294.15 N. According to these results, Group 1 adhere to the bone model 206.29% more strongly than those in Group 2 (P = 0.025). In the second study using PCF 10, in Group 3, the average pull-out force was 166.50 N and in Group 4 the average was 42.83 N. According to these results, Group 3 adhere to the bone model 388.74% more strongly than those in Group 4 (P = 0.002). Locking plates are mostly used in osteoporotic bones and this study demonstrated that the single lead head locking spongious screws which is currently used worldwide have a serious technical problem which arouses with difference of the thread pitch distances on the body and on the head causes pull-out failure.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Especially in the past decades, it can be observed that locking plates have been in a rapidly growing industrial process. This may be attributed to the problems experienced in the classical non-locking plates usage in the osteoporotic bone treatment. Locking plates have very satisfactory results, especially in the fixation of osteoporotic bones, periprosthetic fractures and comminuted fractures1. Axial, torsional, and bending forces at three points need to be neutralized for bone fixation2. In non-locking compression plates, fixation is achieved by the friction forces between the plate and the bone and friction forces are created by the screws pulling the bone through the plate. As a result, primary bone healing occurs without callus formation (endosteal healing)3.

In locking plates, unlike compression plates, there is a rigid and fixed angular connection between the screws and the plate and shear forces converted into compressive forces at the screw-bone interface2. In addition, screws resist the deforming forces as a unified structure with the plate with forces distributed across all screws2,4. Locking plates have a flexible fixation that allows three-dimensional micro-movement between bone fragments and resulting in secondary bone healing with callus formation (enchondral healing)3,5. Locking plates provide more successful results in osteoporotic bones compared to conventional plates due to these properties1,6. Bone fixation with locking plate creates a better environment for fracture healing which can be called biological fixation, instead of full rigid fixation7.

There are many forms of failure in the fracture fixation of locking and compression plates, and screw pull-out is a failure more frequently observed in compression plates6,8. It is known that the rapidly developing industry produces locking spongious screws. However, they were not described in the original locking plate-screw models. These locking spongious screws are encouraged to be used in osteoporotic bones and metaphyseal regions by the industry. We think that the lack of a scientific basis underlying the production of locking spongious screws, which the industry produces to increase fixation quality, also brings some problems.

Our hypothesis is that the use of locking spongious screws with a single lead on the head in locking plates significantly increases the risk of pull-out and decreases the fixation quality on osteoporotic bone. Our aim is to compare the fixation quality of locking spongious screws in locking plates with the FDA approved original locking plate system with locking cortical screws with a biomechanical study on osteoporotic bone models.

Materials and methods

The pull-out strength of the FDA approved original standard locking plate (“LPS”, Merillife Healthcare, Gujarat, India) and anonymous locking plate using the locking spongious screw (LPuLSS) acquired from the medical market was evaluated in vitro on the osteoporotic bone models. To standardize the tests, we used a sawbone model manufactured by Pacific Research Laboratories (Vashon, Washington). Sawbone model is a solid rigid polyurethane foam manufactured especially for testing screw pullout, insertion and stripping torque. A study by Patel et al. reported that PCF-20 test results gave similar values with a normal density bone and PCF-10 can be considered as a low density osteoporotic human cancellous bone9. To compare osteoporotic human bone, we used two different low density of sawbone models which are PCF 15 and PCF 10 (Pacific Research Laboratories, Vashon, Washington). Each bone model was divided into two groups: one group with LPS and the other group with the LPuLSS.

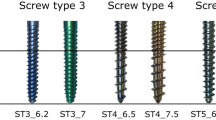

Technical specification of the standart FDA approved original locking screw in LPS we used in the test; screw thread (outer) diameter is 5 mm, screw core diameter is 4.4 mm, screw body thread pitch distance is 1 mm, screw head thread pitch (double lead) distance is 0.5 mm (Fig. 1). To test the screw pull-out, we used a 6-holes 3.5 mm dual hole (with locking and compressing slots) titanium plate (“LPS”, Merillife Healthcare, Gujarat, India) and a 6-holes 3.5 mm dual hole (with locking and compressing slots) titanium locking compression plate acquired from the local medical market.

Technical specifications of the locking spongious screw of locking plate acquired from the medical market we used in the test were that the thread (outer) diameter is 6.5 mm, core diameter is 4.6 mm, screw body thread pitch distance is 3 mm, screw head thread pitch (single lead) distance is 0.8 mm (Fig. 1).

The first study using the PCF 15 bone blocks (Pacific Research Laboratories, Vashon, Washington), the pull-out forces of LPS and LPuLSS were compared using two screws. In this study utilized with PCF 15, the group using LPS was noted as Group 1, and the group using LPuLSS was noted as Group 2. A total of fourteen blocks of the Sawbones PCF 15 artificial bone blocks, each measuring 18 × 45 × 180 mm, were prepared for two groups, 7 blocks for each group. The plates were placed in the middle of the PCF 15 bone blocks. LPS’ were fixated with their original equipment; two guide holes were drilled with a 3.2 mm drillbit using a sleeve at seven cm intervals. Then, two locking screws were locked to the plate using a 3.0 Nm torque screwdriver, with the ends of the screws protruding 5 mm from the other surface. Similarly, LPuLSS’ were prepared on bone models. Guide holes were drilled 3.5 mm in diameter at seven cm intervals using a sleeve. The plates were fixated to the bone models with two locking spongious screws using a 3.0 Nm torque screwdriver, with the ends of the screws protruding 5 mm from the other surface.

In the second study utilized PCF 10 bone blocks, which is more osteoporotic than PCF 15 bone blocks, were used as the bone model. In this study, the pull-out forces of LPS and LPuLSS were compared using a single screw. In this study utilized with PCF 10 bone blocks, the group using LPS was noted as Group 3, and the last group using LPuLSS was noted as Group 4. In group 3, plates were placed in the middle of the PCF 10 bone blocks, and a single guide hole drilled with 3.2 mm drillbit in the center of the plate using a sleeve. One screw was locked to the plate using a 3.0 Nm torque screwdriver, with the end of the screw protruding 5 mm from the other surface. In Group 4, plates were placed on the center of the bone models, and a guide hole drilled with 3.5 mm drillbit at the center of the plate using a sleeve. The locking spongious screw was locked to the plate using a 3 Nm torque screwdriver, with the end of the screw protruding 5 mm from the other surface.

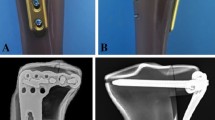

Tests were performed on the Shimadzu AGS-X test machine (Fig. 2) and a pulling apparatus was created for the test (Fig. 3B). Pulling apparatus is a steel plate with a round head that can be covered and held tight by the pulling part of the Shimadzu AGS-X test machine. Cylindrical head hexagonal steel screws used to lock pulling apparatus to the LPS or LPuLSS.

To ensure that the pulling apparatus sits properly on the LPS or LPuLSS and fixed, four screw holes were drilled on each locking plate at appropriate locations before tests were operated (arrows in Fig. 3A). The pulling apparatus was connected with four cylindrical head hexagonal steel screws to the locking plates through these holes prepared on the plates (arrows in Fig. 3B) and the final construct is ready for the test (Fig. 3C). Final construct consists of a PCF-10 or PCF-15 bone model locked with a LPS or LPuLSS and a pulling apparatus sits on locking plate with four cylindrical head hexagonal steel screws to pull the locking plate out of the bone model (Fig. 3C).

The pulling apparatus fixated on each plate-bone models respectively and the force on the pulling apparatus gradually increased with the Shimadzu AGS-X Distraction Machine. While the fixed part of the Shimadzu AGS-X Distraction Machine held the bone block, the pulling apparatus pulled the plate upward, trying to separate the plate and screws from the bone block. The amount of pulling force evaluated on the monitor screen in Newtons, and the moment of separation of the plate and screws from the bone blocks was detected instantly, and these forces were also recorded numerically on the screen.

Results

The results obtained from the tests were presented numerically. In the study using the PCF15 bone model, in Group 1, the mean pull-out force was 606.82 N (IQR25-75; 426.79-883.31). In Group 2, the mean pull-out force was 294.15 (IQR25-75; 140.58–65.95). According to these results, in the study with PCF 15 using two screws, the plates used in Group 1 adhere to the bone model 206.29% strongly than those in Group 2 with a statistically significance result (P = 0.025) (Table 1).

In the results of the study using a single screw and PCF 10, in Group 3, the mean pull-out force was 166.50 N (IQR25-75; 138.96-197.56). In Group 4, the mean pull-out force was 42.83 N (IQR25-75; 33.25–48.47). According to these results, in the study with PCF 10 using a single screw, the plates used in Group 3 adhere to the bone model 388.74% strongly than those in Group 4 with a statistically significance result (P = 0.002) (Table 1).

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics about the data in the study presented with mean and IQR25-75 values. With the use of Mann Whitney U test, the p value of < 0.05 was considered significant in the study.

Discussion

Failure in bone fixation with locking plates is divided into four main categories which are plate breakage, plate bending, screw pull-out and fracture or locking problem at the screw heads10. The use of locking spongious screws in locking plates, which are still widely used today in many countries, can lead to taking some failure risks from the beginning. In our in vitro study, the pull-out force of the LPuLSS was much lower in osteoporotic bone than the LPS.

The use of locking plates has become more common in recent years, especially in cases where stabilization of osteoporotic bone fractures is crucial, alongside the use of conventional compression plates. As a result of immensely growing industry, there are so many plate and screw models with overlooked or lack of biomechanical specification.

To improve fixation of osteoporotic bone fractures, fixed angles of the locking screws are thought to be another important solution7,11. Although locking plates and fixed angle locking screws emerged as lowering the complications, loosening or screw pull-out is still reported as the most frequent complication among the elderly and osteoporotic patients12,13. In addition, osteoporotic bones tend to have a thin cortex, and the cross-section of the bone becomes wider13. That may force the surgeons to choose locking spongious screws. However, there is not much literature on how and where to use locking spongious screws and no studies demonstrate a better purchase of locking spongious screws in such poor bone.

Our aim in this study was to compare the pull-out resistance of locking spongious screws in locking plates with the FDA approved original locking plate system with locking cortical screws with a biomechanical study on osteoporotic bone models.

Locking plates do not have full rigid absolute stability, as in conventional plates. On the contrary, locking plates allow for stable three-dimensional movement of the fracture and as a result, secondary bone healing with callus formation is acquired14. The use of far cortex locking screws increases callus formation by allowing three-dimensional micro movement at the fracture line15.

The most important issue in locking plates is that when the screw head starts to lock into the slot in the plate, the screw equally travels in the slot and bone in each full turn. In the original standard locking plates, although it seems that the thread distance on the screw body and the screw head different, in order to ensure this equality, the screw head began locking in two-way design (double lead) in the screw head. This design magnifies the head screw thread diameter two times in the screw head16. Thus, an equalization is achieved between the distances of thread diameters of the screw body and the screw head. In this way, during locking, the screw travels equally in the bone and in the slot in the plate in each full turn (Video 1).

In original standard locking plates, spongious screws can be used without locking properties. However, some manufacturers in many countries around the world produce locking spongious screws.

The use of 4 mm locking spongious screws in the Anatomic Locking Plating Systems (ALPS) (Zimmer-Biomet), which have been in use since 2008, was banned by the Australian TGA (official agency equivalent to the FDA in the United States) in 2015. The reason for the ban was that the locking threads on the screw head with a single lead instead of a triple lead may not fully engage in the plate slot, leading to insufficient locking of the screw-plate connection and the unseated screw head may cause soft tissue irritation. As a result, a revision surgery may require17. These complications can be encountered in bones with a healthy density. However, there would be another complication which is not mentioned in this Australian TGA report is that the risk of fixation failure due to inadequate screw anchorage in patients with osteoporotic bone structure increases17. As a result of our study, it has been revealed that screw-bone connection weakens even if a torque screwdriver is used with the use of a single lead head locking spongious screws.

In locking plate with locking spongious screw applications, after the screw sits in its slot on the plate, locking starts with the threads on the screw head gripping the threads in the slot on the plate. For each full turn, the screw body tries to advance according to the body thread pitch distance it created in the osteoporotic bone. In the head part of the screw, when it sits in the slot on the plate, the screw can only advance according to the thread pitch distance of the single lead screw head. As a result of this difference of thread pitch distance, while the head starts locking, screw body could not advance in the osteoporotic bone properly and the threads on the body of the screw break all the threads it created in the osteoporotic bone. As a result, the attachment of the screw to the osteoporotic bone becomes severely weakened, and it can only function as a locking nail (Video 2).

We studied two different bone models with same preparates on PCF15 and PCF-10 which is lower density bone model. In the study, using two locking screws on Sawbone PCF 15 osteoporotic bone model, the pull-out force of the LPS was found to be approximately 206.29% stronger than the LPuLSS. In the study with a single locking screw using more osteoporotic bone model Sawbone PCF 10, the pull-out force of the LPS was found to be 388.74% stronger than the LPuLSS. As osteoporosis increases, the pull-out force of locking spongious screws used with locking plates decreases even further.

Larger screw thread diameter in locking spongious screws does not improve the pull-out strength, in contrast it worsens fixation especially in osteoporotic bones because of the thread pitch design in the screw body and the head. The real reason of locking spongious screw pull-out failure in this study was a conclusion of the improper thread design. Slots in the locking plates are made for locking cortical screws. Locking spongious screws should be made in same thread pitch design with the locking cortical screw in the head to properly fit on the slot on the plate. However, thread pitch distance in the screw body differs from each other.

To give an example with numbers; in our study, the thread pitch distance on the body of the locking spongious screws is 3 mm, while the pitch distance on the screw head is 0.8 mm. Since the locking is completed after at least 1.5 turns, the single lead screw head can travel 1.5 × 0.8 = 1.2 mm in its slot in the plate, while the body of locking spongious screw must travel 1.5 × 3 = 4.5 mm in the bone. There is a gap of 3.3 mm which may cause breakage of the threads in the bone. In contrast, the screw head of LPS has a double lead design with 0.5 mm thread pitch distance which equals to 1 mm and body of the locking screw has a thread pitch distance of 1 mm resulting same travel distance in the bone and in the plate.

In clinical practice, many surgeons change their screw preference to locking spongious screws in case of osteoporotic patients or metaphysial regions such as proximal tibia. Even though, locking spongious screws thought to be more effective in such cases, this study demonstrates a worse pull-out force performance in osteoporotic bone models, and if the density decreases further, locking spongious screws may lead to a failure in such cases.

To address the failure of locking spongious screws in osteoporotic bones, we demonstrated a novel design of locking spongious screw with a new thread design. Our improved thread design in the screw head and body demonstrated a better pull-out performance than the locking cortical screws in osteoporotic bone models18.

There are limitations in this study. First, this study was conducted in vitro with sawbone models and does not precisely replicate the clinical situation. Second, this study only demonstrates the pull-out failure and it is not the only failure reason in fracture fixation and clinical reflections may alter especially in stronger bone constructs. Clinical outcome studies are needed to confirm the observations of this in vitro biomechanical study.

Conclusion

The use of locking plates in bone fixation is a revolution. The success of bone fixation depends on the sufficient strength of the screws to hold to the bone. Locking plates are mostly used in osteoporotic bones and our in vitro study demonstrated the locking spongious screws with single lead which used in osteoporotic bone have a serious technical problem which arouses with the pull-out failure and finally bone fixation gets weak. By proving the disadvantages of single lead head locking spongious screws, which are widely used around the world, we wanted to emphasize that caution should be exercised in the use of such materials, especially in patients with osteoporotic bone structure.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request (Dr Fatih Parmaksizoglu, drfatihpar@gmail.com).

References

MacLeod, A. R. & Pankaj, P. Pre-operative planning for fracture fixation using locking plates: device configuration and other considerations. Injury 49, S12–S8 (2018).

Kubiak, E. N., Fulkerson, E., Strauss, E. & Egol, K. A. The evolution of locked plates. JBJS 88(suppl_4), 189–200 (2006).

Egol, K. A., Kubiak, E. N., Fulkerson, E., Kummer, F. J. & Koval, K. J. Biomechanics of locked plates and screws. J. Orthop. Trauma 18(8), 488–493 (2004).

Rothberg, D. L. & Lee, M. A. Internal fixation of osteoporotic fractures. Curr. Osteoporos. Rep. 13, 16–21 (2015).

Elkins, J. et al. Motion predicts clinical callus formation: construct-specific finite element analysis of supracondylar femoral fractures. J. bone Joint Surg. Am. Volume 98(4), 276 (2016).

Bel, J-C. Pitfalls and limits of locking plates. Orthop. Traumatology: Surg. Res. 105(1), S103–S9 (2019).

Gardner, M. J., Helfet, D. L. & Lorich, G. Has locked plating completely replaced conventional plating? Am. J. ORTHOPEDICS-BELLE MEAD- 33, 440–446 (2004).

Dickson, K. F. & Munz, J. W. Locked plating: Biomechanics and biology. Techniques Orthop. 22(4), E1–E6 (2007).

Patel, P. S. D., Shepherd, D. E. T. & Hukins, D. W. L. Compressive properties of commercially available polyurethane foams as mechanical models for osteoporotic human cancellous bone. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 9(1), 137 (2008).

Strauss, E. J., Schwarzkopf, R., Kummer, F. & Egol, K. A. The current status of locked plating: the good, the bad, and the ugly. J. Orthop. Trauma 22(7), 479–486 (2008).

Bottlang, M., Doornink, J., Byrd, G. D., Fitzpatrick, D. C. & Madey, S. M. A nonlocking end screw can decrease fracture risk caused by locked plating in the osteoporotic diaphysis. JBJS 91(3), 620–627 (2009).

Sommer, C., Gautier, E., Müller, M., Helfet, D. L. & Wagner, M. First clinical results of the Locking Compression plate (LCP). Injury 34, B43–54 (2003).

MacLeod, A. R., Simpson, A. H. R. & Pankaj, P. Age-related optimization of screw placement for reduced loosening risk in locked plating. J. Orthop. Res. 34(11), 1856–1864 (2016).

Döbele, S. et al. DLS 5.0-the biomechanical effects of dynamic locking screws. PloS One. 9(4), e91933 (2014).

Nanavati, N. & Walker, M. Current concepts to reduce mechanical stiffness in locked plating systems: a review article. Orthop. Res. Reviews 91–95. (2014).

Cronier, P. et al. The concept of locking plates. Orthop. Traumatology: Surg. Res. 96(4), S17–S36 (2010).

Website:. Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care 03.12.2015. https://www.tga.gov.au/safety/recall-actions/anatomic-locked-plating-system-4-mm-cancellous-locking-screws-used-treat-broken-bones. Accessed May 6. (2024).

Parmaksizoglu, F., Kilic, S. & Cetin, O. A novel model of locking plate and locking spongious screw: a biomechanical in vitro comparison study with classical locking plate. J. Orthop. Surg, Res. 19(1), 237 (2024).

Acknowledgements

We thank to the engineer Burakhan Alyar for his technical support and analyzing for the biomechanical tests.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

FP contributed to the study design, data collection, analysis and manuscript preparation. OC contributed to the data collection, analysis and manuscript preparation. SK contributed to the data collection and analysis. YI contributed study design. All authors read and approved of the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Material 1

Supplementary Material 2

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Parmaksizoglu, F., Cetin, O., Kilic, S. et al. A biomechanical study of locking spongious screws and failure rates are higher than expected in plate fixation. Sci Rep 15, 2728 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87045-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87045-0