Abstract

Sarcopenia, a syndrome characterized by declining muscle mass and function, is associated with various adverse health outcomes. While body mass index (BMI) is a fundamental health indicator, its relationship with sarcopenia is complex and remains inadequately explored. Low BMI has been linked to muscle loss, but the role of other demographic and clinical factors in this relationship is unclear. This cross-sectional study analyzed data from the NHANES 2011–2018 cohort, including 7,455 adults aged ≥ 20 years. Low muscle mass was diagnosed based on appendicular skeletal muscle mass using DXA criteria. BMI was categorized into quartiles for analysis. Weighted multivariable logistic regression assessed associations between BMI and low muscle mass, adjusting for confounders such as age, gender, ethnicity, income-to-poverty ratio, and chronic diseases (e.g., diabetes and hypertension). Variance inflation factors (VIF) confirmed the absence of multicollinearity. Lower BMI was significantly associated with higher odds of low muscle mass (adjusted OR: 0.508, 95% CI: 0.483–0.533, p < 0.001), while higher BMI exhibited a protective effect. Age (OR: 1.035, 95% CI: 1.025–1.045, p < 0.001) and female gender (OR: 1.570, 95% CI: 1.267–1.949, p < 0.001) were independent risk factors. Racial disparities were noted, with non-Hispanic Black individuals at lower risk compared to non-Hispanic Whites (OR: 0.242, 95% CI: 0.152–0.384, p < 0.001). Other significant factors included diabetes and alcohol consumption, while education and smoking status were not significantly associated. BMI is inversely associated with low muscle mass prevalence, with lower BMI posing a higher odds. The findings underscore the clinical importance of monitoring BMI and addressing multifactorial risk profiles for low muscle mass management and prevention.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the global trend of population aging, sarcopenia has emerged as a significant factor in global health, often contributing to numerous adverse health outcomes1,2,3,4,5,6. BMI, as an indicator for predicting various health issues, has served as a fundamental variable in constructing numerous predictive models7,8. However, the relationship between BMI and sarcopenia remains insufficiently recognized and managed in clinical practice.

Sarcopenia is a syndrome characterized by a decline in muscle function and mass, with its prevalence varying significantly across different populations1. Although BMI is an important indicator of individual health status and is typically associated with obesity when elevated, a decrease in BMI can also reflect a loss of muscle mass9, thereby increasing the risk of sarcopenia. Current studies suggest that low BMI and low muscle mass may coexist, exacerbating the risk of adverse health outcomes in older populations10. While the relationship between BMI and low muscle mass continues to be explored, their combination may potentially amplify their detrimental effects on health.

Although certain studies have provided initial insights into the association between BMI and low muscle mass, the epidemiological characteristics across diverse populations remain inadequately understood. Prior studies have focused on older adults or specific subgroups, and often lack the diverse, nationally representative data needed to examine racial and demographic variability11,12. Therefore, this study aims to evaluate the prevalence of BMI and low muscle mass in different populations by analyzing a large sample of healthy participants from the NHANES 2011–2018 database, providing new scientific evidence for clinical management and preventive measures.

Patients and Methods

Study design

This study was a cross-sectional analysis using data collected from the NHANES between 2011 and 2018. The NHANES protocol was approved by the Ethics Review Board of the National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and all participants provided written informed consent. This study utilized data on BMI and low muscle mass obtained through anthropometric measurements and imaging methods.

Covariates

The analysis incorporated a comprehensive set of potential confounders, including age, gender, body mass index (BMI; calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared), educational attainment (classified as low, middle, or high), family income-to-poverty ratio (categorized as below or at/above the poverty threshold), ethnicity (Mexican American, Other Hispanic, non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, and other/multi-racial), presence of hypertension, presence of diabetes, smoking status (current or non-smoker), and alcohol consumption status (drinker or non-drinker). The study incorporated hypertension and diabetes, two of the most representative chronic conditions with high data completeness, as covariates. Smoking and alcohol consumption, the most prevalent adverse behaviors, were included as additional covariates for analysis.

Patients

Participants were included from the NHANES database based on the following criteria: (1) Aged 20 years or older. (2) BMI less than 50. (3) Complete data for key variables (BMI and sarcopenia status). Exclusion criteria included: (1) Age under 20 years. (2) BMI greater than or equal to 50. (3) Missing data on key variables.

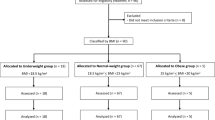

A total of 39,156 participants from the NHANES 2011–2018 dataset were initially identified. Exclusions were made for individuals with missing data on critical variables: 21,273 participants lacked appendicular lean mass index (ALMI) measurements, 14,030 had no recorded hypertension status, 1,552 were missing diabetes data, and 4,738 lacked body mass index (BMI) values. Additionally, exclusions were made due to missing covariate data, including 15,636 for smoking history, 23,550 for alcohol consumption history, 16,539 for education level, and 3,908 for the income-to-poverty ratio. After applying these exclusions, the final analytic sample consisted of 7,455 participants. Based on our inclusion and exclusion criteria, a total of 7,455 individuals were ultimately included in the analysis (Fig. 1).

Measurement

The diagnosis of low muscle mass requires an assessment of muscle strength or gait speed; however, NHANES lacks sufficient data on grip strength or gait speed. Consequently, the appendicular skeletal muscle mass (ASM) to body mass index (BMI) ratio was utilized as a surrogate indicator. In this study, the diagnostic criteria for low muscle mass were established in accordance with the recommendations of the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People 2 (EWGSOP2), which advocates for the use of dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) to measure the appendicular lean mass index (ALMI). Based on these criteria, low muscle mass is defined as an ALMI of < 7.0 kg/m² in males and < 5.5 kg/m² in females.

Statistical analysis

To enhance sample representativeness, probability sampling weights were applied to account for non-response, oversampling, and stratification bias. Categorical variables were summarized as frequencies and percentages, while continuous variables were expressed as means with standard deviations. Univariate analysis was first conducted to evaluate the associations between BMI, covariates, and the prevalence of low muscle mass. Considering the complex sampling design of NHANES, this study applied the corresponding sampling weights provided by the database to derive nationally representative estimates. Weighted multivariable logistic regression was subsequently performed to adjust for potential confounding factors, including age, gender, ethnicity, diabetes, hypertension, alcohol consumption, smoking status, education level, and income-to-poverty ratio. Variance inflation factors (VIF) were calculated to assess multicollinearity, with VIF > 10 indicating severe collinearity. BMI was also categorized into quartiles and analyzed using logistic regression to evaluate its association with low muscle mass, ensuring robustness of results, We used Q1 (lowest BMI quartile) as the reference category in all regression analyses. All analyses were two-sided, with p < 0.05 considered statistically significant, and conducted using R (version 4.1.1).

Results

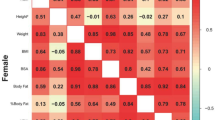

A total of 39,156 participants were initially considered in this study. After applying the exclusion criteria, 7,455 subjects were included in the final analysis, with their baseline characteristics presented in Table 1. Among the included variables, categorical variables consisted of gender, ethnicity, diabetes, hypertension, alcohol consumption, smoking status, education level, and income-to-poverty ratio (Fig. 2). Continuous variables included age and BMI (Fig. 3).

Before performing weighted multivariable analysis, univariate logistic regression was conducted to assess potential risk factors (Table 2). Age (OR: 0.987, p < 0.001) and BMI (OR: 0.530, p < 0.001) were significantly associated with reduced odds, while female gender (OR: 1.783, p < 0.001), education level, ethnicity, hypertension, and alcohol consumption (p < 0.001 for all) were associated with increased odds. Income-to-poverty ratio, diabetes, and smoking status were not significantly associated (p > 0.05).

In the weighted multivariable logistic regression, each one-unit increase in BMI was associated with approximately 49.2% lower odds of low muscle mass (adjusted OR: 0.508, 95% CI: 0.483–0.533, p < 0.001) (Fig. 4). Age was positively associated with low muscle mass prevalence, with each additional year correlating with a 3.51% increase in odds of low muscle mass (OR: 1.035, 95% CI: 1.025–1.045, p < 0.001). Gender also emerged as a significant determinant, with females demonstrating 57.03% higher odds of low muscle mass compared to males (OR: 1.570, 95% CI: 1.267–1.949, p < 0.001). Additionally, the presence of diabetes exhibited a protective association against low muscle mass (OR: 0.533, 95% CI: 0.328–0.879, p < 0.05). Other covariates, including educational attainment, income-to-poverty ratio, race/ethnicity, hypertension, smoking status, and alcohol consumption, were not found to be statistically significantly associated with low muscle mass prevalence in this study (Table 3).

To evaluate the presence of multicollinearity among the covariates included in the multivariable logistic regression model, the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) was calculated for each variable (Table 4). The VIF values ranged from 1.10 to 1.50, which are considerably below the commonly accepted thresholds of 5 or 10. These findings confirm the absence of significant multicollinearity, ensuring the reliability of the regression estimates.

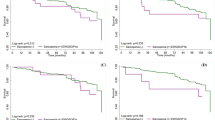

Table 5 presents the results of the weighted multivariable logistic regression examining the relationship between BMI quartiles (Q1–Q4) and low muscle mass, with Q1 serving as the reference group. Notably, Q2 (OR = 0.065, 95% CI: 0.045–0.090, p < 0.001) and Q3 (OR = 0.006, 95% CI: 0.002–0.013, p < 0.001) all showed significantly lower odds of low muscle mass compared with Q1. Female participants demonstrated significantly higher odds of low muscle mass compared to males (OR: 1.623, 95% CI: 1.281–2.058, p < 0.001), and advancing age was positively associated with increased odds of low muscle mass (OR: 1.015, 95% CI: 1.004–1.025, p = 0.005). Furthermore, individuals below the poverty line (OR: 1.316, 95% CI: 1.008–1.715, p = 0.042) and non-drinkers (OR: 1.413, 95% CI: 1.050–1.893, p = 0.021) demonstrated a higher likelihood of low muscle mass. Conversely, non-Hispanic Black individuals exhibited significantly lower odds of low muscle mass compared to non-Hispanic White individuals (OR: 0.242, 95% CI: 0.152–0.384, p < 0.001). Additionally, the absence of diabetes was associated with lower odds of low muscle mass (OR: 0.453, 95% CI: 0.254–0.829, p = 0.009). Other covariates, including education level, smoking status, and hypertension, were not significantly associated with low muscle mass (Fig. 5).

Discussion

This study leveraged the nationally representative NHANES dataset, which encompasses a large, heterogeneous sample spanning diverse age groups, racial and ethnic backgrounds, and socioeconomic strata. This robust design enhances the external validity and generalizability of our findings to the broader U.S. adult population. This study indicate a significant negative correlation between BMI and the prevalence of low muscle mass, consistent with previous studies in the field13,14. We recognize that age is an important factor that cannot be overlooked in the development of sarcopenia15. But sarcopenia may also occur across different age groups16. In a retrospective study, Jung et al. found that 1 in 10 young individuals suffers from sarcopenia across most ethnicities, which may be attributed to various factors such as vitamin D deficiency17, gastrointestinal disorders18, and malignancies10. Therefore, this study selected a broader population range to ensure that no age-related bias would arise in our study of the association between BMI and sarcopenia prevalence.

Our analysis shows that a lower BMI range, particularly values below 18.5, is closely associated with higher odds of low muscle mass. Diabetes and hypertension, as the most common chronic conditions, have widespread effects on the progression of other diseases19. Therefore, we included the influence of hypertension and diabetes when assessing the impact of BMI on the prevalence of low muscle mass. Consistent with findings from other studies, the prevalence of sarcopenia among diabetic patients varies significantly with changes in BMI20, suggesting that these conditions may exacerbate the effect of low BMI on muscle loss21. Moreover, while univariate logistic regression initially showed a statistically significant association between hypertension and the prevalence of sarcopenia22, this relationship was not as significant after multivariable weighted analysis. In certain cardiovascular diseases, sarcopenia is still considered a factor that mutually influences the development of cardiovascular conditions23,24.

This study identified significant racial disparities in low muscle mass prevalence, with non-Hispanic Black individuals exhibiting markedly lower odds of low muscle mass compared to non-Hispanic White individuals (OR: 0.242, 95% CI: 0.152–0.384, p< 0.001). This difference may be attributable to the higher skeletal muscle mass and strength observed in non-Hispanic Black populations, potentially influenced by genetic, physiological, or lifestyle factors. These findings underscore the importance of incorporating racial differences into the development of sarcopenia prevention and management strategies. Further investigations are warranted to clarify the mechanisms underlying these disparities, including the potential contributions of socioeconomic status and lifestyle behaviors. The study also analyzed the effects of gender and age, revealing that the association between BMI and low muscle mass was more pronounced in female patients across univariate, multivariable, and quartile analyses. This finding may be attributed to differences in hormonal levels, which play a critical role in muscle mass regulation25. Unsurprisingly, age emerged as a significant factor in this relationship, but low muscle mass was also observed in several younger participants. In this study, we did not observe a significant correlation between educational level or income status.

We found that the relationship between BMI and the prevalence of low muscle mass is not a straightforward one. Subjects with a BMI of less than 18.5 exhibited a higher prevalence of low muscle mass, whereas those with a BMI greater than 25 showed a markedly lower prevalence. According to Cruz-Jentoft et al., individuals with obesity often have higher muscle mass, which may obscure the presence of sarcopenia1. Dramé et al. suggest that a higher BMI typically reflects a state of obesity, where patients often have a greater absolute muscle mass. This increased muscle mass may provide better nutritional reserves and a stronger metabolic capacity, enabling a certain level of physiological resistance to acute or chronic illnesses26. The current findings indicate that the obesity paradox does not apply to all patients but is more relevant to those with chronic heart or kidney diseases27.

The lower prevalence of low muscle mass observed in individuals with higher BMI could also reflect the obesity paradox. Sarcopenia is often associated with frailty and various adverse outcomes; however, a higher BMI can demonstrate better survival rates and lower frailty in certain diseases. Eitmann et al., through a systematic review and meta-analysis, found that excess obesity may exacerbate health conditions in patients with sarcopenia, but among sarcopenic patients aged over 65, those with obesity tend to have a longer life expectancy compared to those without obesity28. We suggest that when considering patients with a higher BMI, the concept of sarcopenia should not be applied in the usual sense, as individuals with a higher BMI do not necessarily exhibit symptoms of frailty and may even have a protective effect against mortality in frail populations29,30. Sarcopenia is associated with frailty, which leads to numerous adverse outcomes31. We believe that in cases of higher BMI, low muscle mass should be reinterpreted from a new perspective, such as evaluating whether the risk of various diseases is increased or whether mortality rates are elevated. Discussions should focus on new diagnostic and prognostic considerations specific to sarcopenic obesity, rather than treating them equivalently to individuals with normal or low BMI.

BMI as a simple anthropometric index, may not accurately differentiate between fat mass and lean body mass. In a prospective cohort study, Lee et al. examined the associations of predicted lean body mass, fat mass, and BMI with all-cause and cause-specific mortality in male32. The study revealed a U-shaped relationship between lean body mass and all-cause mortality, with individuals in the middle quintiles of lean body mass exhibiting a lower risk of mortality compared to those in the lowest quintile. These findings suggest that the relationship between BMI and mortality is primarily determined by the influence of lean body mass and fat mass. This may provide insight into the “obesity paradox,” particularly at lower BMI levels, where low lean body mass, rather than low fat mass, may serve as the predominant factor. In our study, a higher BMI may reflect greater muscle reserves, thereby reducing the odds of low muscle mass. However, BMI does not account for the specific distribution of fat and muscle, which limits its utility in evaluating sarcopenia. Future research on sarcopenia should incorporate measurement methods that more accurately reflect muscle mass.

Our results emphasize the need for routine assessment of muscle health in individuals at both ends of the BMI spectru. Physicians and other healthcare providers may prioritize the evaluation of muscle strength in individuals identified with low muscle mass and implement tailored interventions, including protein supplementation, resistance exercise programs, and physical therapy, to address and mitigate the associated health risks. In the context of public health policy, early screening for low BMI represents a practical approach for identifying populations with an elevated odds of low muscle mass, particularly in resource-constrained community settings. Targeted interventions addressing this risk have the potential to significantly reduce the incidence and healthcare burden associated with frailty, functional decline, and the adverse outcomes of sarcopenia. Furthermore, prospective cohort studies and randomized clinical trials are warranted to elucidate the causal mechanisms and refine targeted intervention strategies for distinct BMI subgroups. The assessment of muscle mass is essential and should not be underestimated, as it is a critical factor in evaluating the healing process of various diseases33,34. Although this study lacks data on physical function, the evaluation of muscle mass still provides a strong basis for the diagnosis of sarcopenia.

This study have several limitations. First, the cross-sectional design limits our ability to establish a causal relationship between BMI and sarcopenia. Second, the use of DXA for diagnosing sarcopenia may have some inaccuracies, such as measuring skeletal muscle instead of lean mass35,36. Finally, due to data limitations, we were unable to use muscle function criteria for the diagnosis of sarcopenia, in selecting covariates for inclusion, chronic conditions such as dementia, cancer, and respiratory diseases were not included in the study. Future research should incorporate more direct measurement methods to validate our findings and provide a more comprehensive understanding of the risk factors for sarcopenia.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates a complex relationship between BMI and sarcopenia, with lower BMI levels associated with a higher prevalence of sarcopenia and higher BMI levels associated with a lower prevalence, indicating a negative correlation between BMI and sarcopenia prevalence. Sarcopenia was also observed in younger participants. These findings provide new insights into the interaction between body composition and muscle health, suggesting the need for personalized approaches in clinical management and prevention strategies.

Acknowledgements.

Data availability

The data used in this study were obtained from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) database. NHANES is a publicly available dataset provided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in the United States. The data can be accessed at the NHANES website (https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/index.htm).

References

Cruz-Jentoft, A. J. & Sayer, A. A. Sarcopenia [published correction appears in Lancet. ;393(10191):2590. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31465-5]. Lancet. 2019;393(10191):2636–2646. (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31138-9

Gao, Q. et al. Associated factors of Sarcopenia in Community-Dwelling older adults: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Nutrients 13 (12), 4291. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13124291 (2021).

Huang, P. et al. Sarcopenia as a risk factor for future hip fracture: a Meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. J. Nutr. Health Aging. 25 (2), 183–188. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-020-1474-5 (2021).

Feng, L. et al. Prevalence and risk factors of Sarcopenia in patients with diabetes: a Meta-analysis. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 107 (5), 1470–1483. https://doi.org/10.1210/clinem/dgab884 (2022).

Tantai, X. et al. Effect of Sarcopenia on survival in patients with cirrhosis: a meta-analysis. J. Hepatol. 76 (3), 588–599. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2021.11.006 (2022).

Wang, L. et al. Muscle size and density are independently associated with death after hip fracture: a prospective cohort study. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 14 (4), 1824–1835. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcsm.13261 (2023).

Aune, D. et al. BMI and all cause mortality: systematic review and non-linear dose-response meta-analysis of 230 cohort studies with 3.74 million deaths among 30.3 million participants. BMJ 353, i2156. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i2156 (2016). Published 2016 May 4.

Bradbury, K. E. & Cairns, B. J. Understanding the relation between BMI and mortality. BMJ 364, l1219. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l1219 (2019). Published 2019 Mar 26.

Suthahar, N. et al. Associations of relative fat mass and BMI with all-cause mortality: confounding effect of muscle mass. Obes. (Silver Spring). 32 (3), 603–611. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.23953 (2024).

Kiss, N. et al. Low muscle mass, malnutrition, Sarcopenia, and associations with survival in adults with cancer in the UK Biobank cohort. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 14 (4), 1775–1788. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcsm.13256 (2023).

Scott, D. et al. Sarcopenic obesity and dynapenic obesity: 5-year associations with falls risk in middle-aged and older adults. Obes. (Silver Spring). 22 (6), 1568–1574. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.20734 (2014).

Batsis, J. A. & Villareal, D. T. Sarcopenic obesity in older adults: aetiology, epidemiology and treatment strategies. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 14 (9), 513–537. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41574-018-0062-9 (2018).

Curtis, M., Swan, L., Fox, R., Warters, A. & O’Sullivan, M. Associations between Body Mass Index and probable Sarcopenia in Community-Dwelling older adults. Nutrients 15 (6), 1505. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15061505 (2023). Published 2023 Mar 21.

Altaf, S. et al. Prevalence and associated risk factors of Sarcopenia in community-dwelling older adults in Pakistan: a cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr. 24 (1), 497. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-024-05111-0 (2024). Published 2024 Jun 5.

Lisco, G. et al. Sarcopenia and Diabetes: a detrimental Liaison of advancing age. Nutrients 16 (1), 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16010063 (2023). Published 2023 Dec 25.

Jung, H. N., Jung, C. H. & Hwang, Y. C. Sarcopenia in youth. Metabolism 144, 155557. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.metabol.2023.155557 (2023).

Remelli, F., Vitali, A., Zurlo, A. & Volpato, S. Vitamin D Deficiency and Sarcopenia in older persons. Nutrients 11 (12), 2861. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11122861 (2019). Published 2019 Nov 21.

Zhang, Y. et al. Impact of malnutrition and sarcopenia on quality of life in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a multicentre study. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 14 (6), 2663–2675. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcsm.13341 (2023).

Horton, W. B. & Barrett, E. J. Microvascular Dysfunction in Diabetes Mellitus and Cardiometabolic Disease. Endocr. Rev. 42 (1), 29–55. https://doi.org/10.1210/endrev/bnaa025 (2021).

Bellary, S., Kyrou, I., Brown, J. E. & Bailey, C. J. Type 2 diabetes mellitus in older adults: clinical considerations and management. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 17 (9), 534–548. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41574-021-00512-2 (2021).

Aluganti Narasimhulu, C. & Singla, D. K. Amelioration of diabetes-induced inflammation mediated pyroptosis, Sarcopenia, and adverse muscle remodelling by bone morphogenetic protein-7. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 12 (2), 403–420. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcsm.12662 (2021).

Bai, T. et al. Sarcopenia is associated with hypertension in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Geriatr. 20 (1), 279. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-020-01672-y (2020). Published 2020 Aug 6.

Bielecka-Dabrowa, A. et al. Cachexia, muscle wasting, and frailty in cardiovascular disease. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 22 (12), 2314–2326. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejhf.2011 (2020).

Damluji, A. A. et al. Sarcopenia and Cardiovascular diseases. Circulation 147 (20), 1534–1553. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.123.064071 (2023).

Chlebowski, R. T. et al. Association of menopausal hormone therapy with breast Cancer incidence and mortality during Long-Term follow-up of the women’s Health Initiative Randomized clinical trials. JAMA 324 (4), 369–380. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.9482 (2020).

Dramé, M. & Godaert, L. The obesity Paradox and Mortality in older adults: a systematic review. Nutrients 15 (7), 1780. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15071780 (2023). Published 2023 Apr 6.

Tutor, A. W., Lavie, C. J., Kachur, S., Milani, R. V. & Ventura, H. O. Updates on obesity and the obesity paradox in cardiovascular diseases. Prog Cardiovasc. Dis. 78, 2–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcad.2022.11.013 (2023).

Eitmann, S. et al. Obesity paradox in older sarcopenic adults - a delay in aging: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res. Rev. 93, 102164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2023.102164 (2024).

Jayanama, K. et al. Relationship of body mass index with frailty and all-cause mortality among middle-aged and older adults. BMC Med. ;20(1):404. Published 2022 Oct 24. (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-022-02596-7

Watanabe, D. et al. Frailty modifies the association of body mass index with mortality among older adults: Kyoto-Kameoka study. Clin. Nutr. 43 (2), 494–502. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2024.01.002 (2024).

Dent, E. et al. Management of frailty: opportunities, challenges, and future directions. Lancet 394 (10206), 1376–1386. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31785-4 (2019).

Lee, D. H. et al. Predicted lean body mass, fat mass, and all cause and cause specific mortality in men: prospective US cohort study. BMJ 362, k2575. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.k2575 (2018). Published 2018 Jul 3.

Han, J. & Kim, W. Prognostic implications of trunk muscle mass in liver cirrhosis. Clin. Mol. Hepatol. 24 (3), 297–298. https://doi.org/10.3350/cmh.2018.0069 (2018).

Rossi, F. et al. Muscle mass loss in breast cancer patients of reproductive age (≤ 45 years) undergoing neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Radiol. Med. 128 (1), 49–57. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11547-022-01574-6 (2023).

Coletta, G. & Phillips, S. M. An elusive consensus definition of Sarcopenia impedes research and clinical treatment: a narrative review. Ageing Res. Rev. 86, 101883. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2023.101883 (2023).

Zamboni, M., Rubele, S. & Rossi, A. P. Sarcopenia and obesity. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care. 22 (1), 13–19. https://doi.org/10.1097/MCO.0000000000000519 (2019).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the use of data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2011–2018, which was made publicly available by the National Center for Health Statistics. We also thank the participants of NHANES for their contribution to this study.

The authors would like to acknowledge the use of data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2011–2018, which was made publicly available by the National Center for Health Statistics. We also thank the participants of NHANES for their contribution to this study.

Funding

There is no funding.

Consent to participateInformed consent was obtained from all participants.

Consent to publishAll authors are consent to publish.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

XRZ: Study design, wrote the text, performed software analysis. LXS: Study design, wrote the text. ZFD: Performed software analysis. LGQ: Performed software analysis. ZWQ: Conducted literature search. LYF: Conducted literature search. HJF: Study design and supervision, wrote the text, collected cases.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest related to this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xie, RZ., Li, XS., Zha, FD. et al. Relationship Between Body Mass Index and Low Skeletal Muscle Mass in Adults Based on NHANES 2011–2018. Sci Rep 15, 2596 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87176-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87176-4

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Undernutrition and associated factors among adult cancer patients in northwest Ethiopia: a global leadership initiative on malnutrition-based approach

BMC Cancer (2025)

-

Impact of the hemoglobin-to-red cell distribution width ratio on 30-day readmission in patients with heart failure

BMC Cardiovascular Disorders (2025)

-

The effect of pain on fear of movement in the early period after open heart surgery according to the fear-avoidance model: the role of moderating factors

BMC Nursing (2025)

-

Is more muscle mass linked to less hypertension? Exploring sex-specific effects and the role of body composition in older European adults

Journal of Public Health (2025)