Abstract

The type of electron acceptor group has a significant effect on the photovoltaic properties of solar cell sensitizers. In this study, on the basis of previous studies of the π1- and π2-linked groups of D-π1-A1-π2-A2-type sensitizers, the photoelectric properties of Ullazine-Based photosensitizing dyes were further optimized by adjusting the electron-absorbing groups at the A1 and A2 positions. DFT and TDDFT calculations revealed that substituting the A1 position with a BTD moiety led to a substantial increase in the light absorption capacity of the dye. Furthermore, the incorporation of a CSSH moiety at the A2 position resulted in a significant redshift of the absorption spectrum and a notable increase in the light trapping efficiency. Moreover, TDM analysis indicates that HOMO→LUMO is the predominant mode of transition in the S0→S1 exciton transition of the dye molecule on the basis of the BTD motif. This mode remains the dominant mode after the introduction of the CSSH motif, although its contribution is reduced. Notably, HJ19 (A1 for BTD, A2 for CSSH) and HJ20 (A1 for difluorosubstituted BTD, A2 for CSSH) dyes demonstrate optimal optoelectronic properties, exhibiting redshifted absorption wavelengths by more than 79 nm and enhanced maximum absorption efficiencies by more than 40% with those of the YZ7 sensitizer.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Dye-sensitized solar cells (DSSCs) have emerged as a significant area of scientific inquiry and industrial advancement, largely because of their favorable cost-performance ratio, extended operational lifespan, exceptional optical characteristics, and robust mechanical durability1,2,3,4,5. Since the pioneering work of O’Regan and Grätzel in 1991, who constructed the first DSSC and achieved a photoelectric conversion efficiency of 7.1%6, this field has continued to flourish, with significant advancements in the fundamental architecture and technological innovation. Recently, the Ren team has made significant progress and reported a high-efficiency DSSC with a power conversion efficiency (PCE) of up to 15.2%7. Under certain conditions, the device performance can even reach an excellent level of 28.4–30.2%7.

The essential constituents of a DSSC include a sensitizer dye, a working electrode, a counter electrode, and an electrolyte. Among these components, the sensitizer dye molecule plays a pivotal role in the photoelectric conversion process, with its performance directly influencing the overall efficiency of the device. In the context of molecular design, organic dye sensitizers typically adhere to the D-π-A configuration principle, comprising an electron donor (D), a conjugated bridge (π), and an electron acceptor (A) unit arranged in a specific sequence8,9,10. In recent years, researchers have continuously explored and designed various derivative structures on the basis of the traditional D-π-A structure, with the aim of further improving the performance of DSSCs. These include the D-D-π-A type11,12, the D-A-π-A type13,14,15, and the particularly eye-catching D-π-A-π-A type16,17. These novel structures have markedly increase the light absorption capacity, charge separation efficacy, and electron transport functionality of the dye molecules by incorporating supplementary electron acceptors, which are ingeniously positioned between the electron donor and acceptor18,19. Notably, the distinctive dual-acceptor configuration of D-π-A-π-A dyes has pioneered new avenues for enhancing the overall performance of DSSCs.

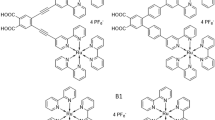

The distinctive molecular configuration of the Ullazine group, a heterocyclic system characterized by a high nitrogen content, is clearly illustrated in Fig. 1a. The core feature of this group is its extensive conjugated system of 16 π-electrons, which significantly enhances its energy harvesting capacity within the visible to ultraviolet range of the solar spectrum, effectively promoting the excitation and transition of electrons. Moreover, the Ullazine group contains a plethora of substitution sites, offering a vast canvas for meticulous calibration of the electron donor strength and the overall conformation and properties of the dye molecule20,21. By employing sophisticated substitution methodologies, researchers can further enhance the photoelectric properties of dyes, thereby addressing the urgent requirements of photoelectric devices such as DSSCs for efficient and stable dye molecules. Our preceding research methodically examined the influence of the π-conjugated group structure on the photoelectric properties of D-π-A-π-A-type solar cell sensitizers. We meticulously designed π-conjugated group-enhanced sensitizers HJ2 and HJ8 with 4,4-dimethylcyclopenta[2,1-b:3,4-b]dithiophene as the core unit (as illustrated in Fig. 1c)17. These two new sensitizers markedly overcame the spontaneous aggregation of the dye resulting from strong π-π interactions in the previous YZ7 sensitizer in the Fig. 1b22, thus representing a significant improvement in photoelectric performance. In particular, the π-conjugated core units in HJ2 and HJ8 demonstrated redshifted spectral absorption, extending to wavelengths of 552 nm and 604 nm, respectively17. This modification broadened the spectral response range and markedly enhanced the maximum extinction coefficient and light capture efficiency, thereby achieving a substantial improvement in photoelectric conversion efficiency in comparison to the original YZ7 sensitizer17. This research deepened our comprehension of the mechanisms underlying the action of π-conjugated groups in D-π-A-π-A-type sensitizers and provides a crucial theoretical foundation and experimental reference for the development of efficient and stable solar cell materials.

Previous experimental research has revealed aggregation in synthesized photosensitizers with a carboxyl (COOH) group anchoring group22,23,24,25. Furthermore, various studies have demonstrated that altering the COOH group to a disulfide carboxyl (CSSH) group may prevent the aggregation of dyes26. Our findings clearly demonstrated that the introduction of a CSSH group at the A2 site can markedly enhance the efficiency of the sensitizer molecule in capturing and converting solar energy in comparison to a COOH group17. The present study is concerned with the impact of A1 and A2 electron acceptor groups on the photoelectric properties of these materials. This research builds upon our previous work17, in which we optimized the π1 and π2 linking groups in Fig. 1c with superior photoelectric properties via DFT/TDDFT methods. The objective is to identify and implement more sophisticated chemical modification strategies for enhancing the photoelectric conversion efficiency of the sensitizer. The 2,1,3-benzothiadiazole (BTD) receptor group and its analogues27,28,29,30 were selected for the electron acceptor group A1 of HJ2 on the basis of previous studies, resulting in the formation of HJ14, HJ15, HJ16, HJ17 and HJ18 dyes. Moreover, the COOH acceptor, A2, was replaced by the CSSH acceptor, yielding the potential solar dyes HJ18, HJ20, HJ21, HJ22 and HJ23, which are depicted in Fig. 2. The A1 group in HJ15 and HJ20 introduced two fluorine electron acceptors on the basis of the original BTD, thereby enhancing the electron acceptance performance of its electron acceptor group. The introduction of a conjugated system on the basis of BTD in HJ16–HJ18 and HJ21–HJ23 served to reduce the energy gap between the energy levels, resulting in a redshifted absorption wavelength.

Methods

Geometry optimization

A number of studies have demonstrated that density functional theory (DFT) can yield reasonable properties of organic dyes in DSSCs17,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39. In particular, PBE0 (PBE1PBE)/6-311 + G** has been identified as a suitable method for the ullazine-based D-π-A-π-A photosensitizers, and the results are in good agreement with experimental findings17. In this study, the structures of the molecules were optimized via the Gaussian 16 program40. To facilitate a more robust comparison with the experimental results22 and our previous findings17, we employed experimental dichloromethane solvation for the DFT calculations in this study. Therefore, the CH2Cl2 solvent with the standard Integral Equation Formalism Polarisable Continuum Model (IEFPCM)41,42 was employed with a dielectric constant of 9.08 for CH2Cl2 solvation. All optimized structures were investigated for the presence of imaginary frequencies.

Excitation energy calculation

Time-dependent density functional theory (TDDFT) has been demonstrated to be an effective method for the accurate calculation of the vertical excitation energy17,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39. The cam-B3LYP43 functional and the 6−311 + G** basis set have been shown to be appropriate for use at optimized geometries obtained by PBE0/6−311 + G** for ullazine-based D-π-A-π-A photosensitizers. The IEFPCM solvation model was employed for the solvation of CH2Cl241,42.

Property calculation

The DFT/TDDFT orbital and transition density matrix (TDM) analyses were corroborated by a Multiwfn analyzer44. The highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) and lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) energies indicate electron transfer capabilities. The performance of the dyes in the DSSCs is evaluated on the basis of the total efficiency of the DSSCs (η). The total efficiency of DSSCs (η) was determined by the short-circuit current density (Jsc), open-circuit voltage (Voc), fill factor (FF), and incident light intensity (Pinc), as illustrated in the following equation45:

The corresponding short-circuit current density (Jsc) can be expressed as follows46:

where LHE(λ) represents the light harvesting efficiency at wavelength λ, while Φinj denotes the charge injection efficiency and ηcoll signifies the electron collection efficiency. Because the I−/I3 − electrode is considered in this study, it can be seen that the value of the electron collection efficiency, ηcoll, is constant. To obtain a high Jsc, LHE(λ) and Φinj would be as large as possible. The light harvesting efficiency (LHE) of the maximum wavelength can be calculated via following formula47:

where f represents the oscillator strength at the wavelength exhibiting the greatest intensity.

The Φinj is evaluated through the injection driving force of the injection Gibbs energy (∆Ginj) which is related to the electron injection efficiency. The ∆Ginj can be expressed as48:

where Edye* is the excited state potential and ECB is the conduction band of semiconductor materials. When considering the semiconductor TiO2, the ECB is usually experimentally set at −4.0 eV in vacuum49. However, in the TDDFT calculations, the potential of the first excited state is rarely the energy of the LUMO. Therefore, ∆Ginj is calculated as follows50:

where Edye is the ground state potential and Eex is the vertical excitation energy corresponding to the calculated maximum absorption wavelength λmax.

∆Greg is used to reflect the power of dye regeneration in electrode I−/I3−, as shown in the following formula51:

where Eredox is the redox potential of electrode I−/I3−, with a value of −4.7 eV52. Edye represents the potential of the ground state.

The lifetime of the excited state is a critical determinant of the charge transfer efficiency, with longer lifetimes conferring greater advantages for charge transfer. A longer excited state lifetime is conducive to enhanced charge transfer. The excited state lifetime (τ) can be calculated via the following equation52:

f and E are the oscillator strength and vertical excitation energy (in cm− 1) of the excitation considered.

Voc in DSSCs can be described as follows53:

Here, q is the unit charge, ECB is the conduction band edge of the semiconductor substrate, kbT is the thermal energy, nc is the number of electrons in the conduction band, NCB is the density of accessible states in the conduction band, and Eredox is the electrolyte Fermi level. The shift in the ECB when the dyes are adsorbed on the substrate, denoted by ∆ECB, can be expressed as follows54:

where q represents the meta charge; µmormal denotes the dipole moment perpendicular to the surface of TiO2; γ signifies the concentration of dyes adsorbed on the surface of the titanium dioxide semiconductor; and ε0/ε is the dielectric constant of the vacuum/organic dyes.

Results and discussion

Optimized geometry

The optimized bonding and dihedral parameters between each donor motif, acceptor motif and π-bridge are presented in Table 1, and the Cartesian coordinates of each optimized geometry are provided in the Supporting Information. A close relationship was observed between the molecular structure of the sensitized solar dyes and their performance, particularly in the case of the planar structure between the donors, acceptors and π-bridges. As shown in Table 1, the previously reported YZ7 molecule exhibited a high degree of planarity, with calculated Φ1, Φ2 and Φ3 values of 1.8°, 0.1° and 0.0°, respectively17. HJ2 and HJ8 presented Φ1, Φ2 and Φ3 values ranging from 29.7° to 35.7°, 4.7° to 8.5° and 17.9° to 18.7°, respectively. YZ7 with C ≡ C is a planar conjugated molecular structure that plays a pivotal role in the spontaneous aggregation of YZ7 molecules. Replacing C ≡ C with C = C results in a twisted structure for HJ1 molecules, thereby reducing the π-π interactions of the planar conjugated molecules and mitigating molecular agglomeration among dye sensitizers17. Upon replacing the A1 electron acceptor 4,4-difluorocyclopenta[2,1-b:3,4-b]dithiophene with the BTD receptor group and its analogs, the resulting molecules retained the nonplanar structure among the D motif, π1 motif and A1 for HJ14–HJ23, with Φ1 and Φ2 dihedral angles ranging from 24.3° to 36.6° and from 7.9° to 14.2°, respectively. The A1, π1 and A2 motifs exhibited a high degree of planarity, as evidenced by the relatively low values of the Φ3 and Φ4 angles, which were approximately 0.2° and 0.3°, respectively, for HJ14 and HJ18. In contrast, the spatial site resistance of the thiophene and benzene ring substituents in HJ16 and HJ17 resulted in a distortion between the A1 and π1 groups. The dyes with CSSH groups presented structural characteristics analogous to those of the carboxyl groups. For example, the optimized R1, R2, R3, R4, Φ1, Φ2, Φ3 and Φ4 parameters of HJ14 were 1.454Å, 1.447Å, 1.449Å, 1.409Å, 34.5°, 14.2°, 0.2° and 0.2°, and the corresponding parameters for HJ19 were 1.453Å, 1.446Å, 1.448Å, 1.401Å, 34.2°, 14.3°,0.0° and 0.3, respectively.

Photoelectric properties

The energy levels of the frontier molecular orbitals are illustrated in Fig. 3. It is imperative to align the energy levels of the dye molecule, titanium dioxide semiconductor, and redox electrolyte to determine the viability of employing the dye molecule in dye-sensitized solar cells. As illustrated in Fig. 3, the LUMO energy levels of the dye molecules were all higher than the conduction band edge of titanium dioxide (− 4.0 eV)49, and the HOMO energy levels were all lower than the potential of the I−/I3 − redox electrolyte pair (− 4.7 eV)52, thereby ensuring that the dye molecules were able to inject electrons into titanium dioxide and facilitate the reduction of the dye molecules in the oxidized state.

Compared with the 4,4-difluoro−4 H-cyclopenta[2,1-b:3,4-b]dithiophene (fCDT) electron acceptor (A1 group for HJ2 or HJ8), the BTD exhibited a diminished HOMO-LUMO energy level difference, which was further diminished due to the expansion of the conjugation space of the BTD. As illustrated in Fig. 3, the orbital energy levels of the LUMO were all greater than − 4.0 eV, whereas the orbital energy levels of the HOMO were all less than − 4.7 eV. These findings indicated that all the designed dyes are capable of functioning correctly with the titanium dioxide substrate and the I−/I3 − redox electrolyte pair. The HJ14 dye with a BTD electron acceptor group exhibited an energetic level similar to that of HJ2 for the HOMO and HOMO−1. However, the LUMO and LUMO + 1 notably decreased, reaching −2.34 eV and −1.66 eV, respectively. This narrowed the HOMO-LUMO gap by 0.1 eV to 3.74 eV in comparison to that of HJ2. The addition of two F atoms to the BTD group resulted in the formation of the HJ15 molecule, which presented lower HOMO and LUMO energies than HJ14 did. However, the HOMO-LUMO energy level difference of 3.74 eV is comparable to that observed in HJ14. Following the addition of the BTD electron acceptor group to HJ16–HJ18, the energy levels of the LUMO and LUMO + 1 notably decreased, whereas those of the HOMO/HOMO−1 slightly increased. It can be inferred that, in the case of A1 electron acceptor groups, the molecular orbital electron distribution was influenced to a greater extent by the conjugation of aromatic hydrocarbons attached to BTD (HJ16–HJ18) than by the induced effect of F atoms attached (HJ15). This resulted in a narrow HOMO-LUMO gap, with a value of 2.77–3.14 eV. The -CSSH in the A2 site would serve to narrow the HOMO-LUMO gap, which was in the range of 2.70 to 3.00 eV, for H21–HJ23.

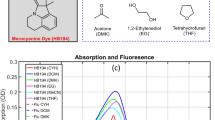

The light absorption capacity of the dye molecules proved to be the determining factor in the photoelectric conversion efficiency of the dyes. The principal characteristics of the selected dyes are presented in Table 2. As illustrated in Table 2, the maximum absorption wavelength λmax of HJ14 (592 nm) exhibited a redshift of 40 nm in comparison to that of HJ2 (552 nm) and 57 nm in comparison to that of YZ7 (535 nm). This redshift can be attributed to the replacement of the fCDT group by the BTD motif. The reduction in the energy levels of the LUMO and LUMO + 1, which resulted from the introduction of the BTD motif, led to a redshift. Compared with HJ14, the difluorinated BTD in HJ15 resulted in a smaller redshift compared to HJ14. This was due to the detrimental impact of induced electron absorption in the electron acceptor motif on the photovoltaic performance, as illustrated in Table 2; Fig. 4. Nevertheless, HJ15 exhibited a redshift of 26 nm from HJ2 and 44 nm from YZ7, rendering it an optimal dye sensitizer. The aromatic BTD resulted in a redshift for HJ16–HJ18, with absorption occurring at 814–1031 nm. The wavelength range of 814 nm to 1031 nm is not within the visible spectrum. The intensity of sunlight within this wavelength band is constrained, which renders HJ16–HJ14 unsuitable for use as a dye sensitizer in solar cells. The maximum extinction coefficients for HJ2 and HJ7 were lower than that of the HJ2 dye, but still exhibited values that were 13–14% greater value than that of YZ7. HJ14 and HJ15 presented a high maximum extinction coefficients (ε), with values of 8.280 × 104 M − 1·cm − 1 and 8.392 × 104 M − 1·cm − 1, respectively. Additionally, they demonstrated a notable light harvesting efficiency, with a value of 99.0% for both.

The presence of the disulfide carboxyl acceptor at the A2 site further enhances the redshift of the absorption spectrum, a phenomenon that was previously predicted in our own research17. The maximum absorption wavelengths (λmax) of HJ19 and HJ20 were observed to be 632 nm and 614 nm, respectively. There was a notable redshift of 97 nm and 79 nm to YZ7 (535 nm), and a slight redshifts of 28 nm and 10 nm to HJ8 (604 nm). The D-π-A-π-A type, in conjunction with the CSSH acceptor, demonstrated a 41% and 42% increase in the spectral absorbance intensity, respectively. Moreover, 99.7% light harvesting efficiency was achieved for both the HJ19 and HJ20 dyes. Furthermore, the calculated UV-Vis spectroscopy data illustrated in Fig. 4 demonstrated that HJ19 and HJ20 exhibited substantial absorption in long-wavelength sunlight, particularly within the range of 500 to 700 nm. In contrast, the original YZ7 demonstrated a predominant absorption at wavelengths within the range of 500 to 600 nm. The absorption spectra of HJ21–HJ23 were within the infrared region, between 856 and 1076 nm, and exhibited reduced a absorption intensity relative to that of YZ7. Consequently, these materials are unsuitable for use as dye sensitizers in solar cells. Furthermore, the lifetime of the excited state was identified as a critical factor influencing the charge transfer efficiency. A longer excited state lifetime was observed to enhance the charge transfer efficiency55. The first excited state lifetimes of HJ19 and HJ20 were 2.37 ns and 2.24 ns, respectively, which ensured efficient electron transfer and injection of dye molecules. It was therefore concluded that HJ19 and HJ20 were the optimal sensitized dyes, exhibiting the most favourable photoelectric performance within the series.

Furthermore, the mechanism underlying the enhancement in efficiency observed in the contribution of the D-π-A-π-A type and CSSH acceptor can be elucidated through the TDDFT orbital analysis illustrated in Table 2; Fig. 5. In the D-π-A-π-A-type dyes HJ14, HJ15, HJ16 and HJ17, the HOMO electronic distribution was observed in the D1, π1 and A1 regions, whereas the LUMO exhibited an expansion in the π1, A1, π2 and A2 regions, a finding that aligns with our previous study17. For the maximum absorption wavelength λmax, as shown in Table 2, the HOMO→LUMO excitation is dominant in the D-π-A dyes, accounting for 69.7% of the YZ7. When the fCDT insert is placed in the A1 site to form HJ2, the contribution of HOMO→LUMO excitation decreases to 38.8%. However, the use of BTD and difluorinated BTD motifs resulted in a slight decrease in the contribution of HOMO→LUMO excitation, from 63.3% and 65.6–60.6% and 63.3%, respectively. In contrast to our earlier fCDT electron acceptor sensitizers, the primary contributing transition in the first excited state of the dye molecule based on the BTD acceptor is, in agreement with YZ7, a HOMO→LUMO transition rather than a HOMO−1→LUMO transition. The CSSH acceptor resulted in a decrease in the contribution of 6.4% and 4.1–63.3% and 65.6%, respectively. The substitution of the carboxyl group at the A2 site with a CSSH group is predicted to result in a further reduction in the proportion of HOMO→LUMO, which increases to approximately 50%. Nevertheless, despite this reduction, the HOMO→LUMO excitation continues to represent the dominant form of the S0→S1 spectrum. The primary electronic transition component of HJ19 and HJ20 was identified as HOMO→LUMO excitation, which accounted for contributions of 54.6% and 52.3%, respectively. The secondary transition was found to be HOMO−1→LUMO excitation, which contributed 27.2% and 28.1%, respectively.

Photovoltaic properties of DSSCs

It is essential to consider the photovoltaic properties when integrating dyes into solar cells. The electrons from the donor motifs of the dye are transferred to the acceptor motifs, which are induced by sunlight, and subsequently injected into the semiconductor films and solar cell utility. The Gibbs free energy change, ∆Ginj, is indicative of the driving force governing the injection of electrons. Conversely, the electrons of the dye are replenished and regenerated by the redox electrode, the driving force of which is determined by the parameter ∆Greg. As shown in Table 3, the ∆Ginj and ∆Greg values for HJ14–HJ17, HJ19 and HJ20 were greater than 1.0 eV. In accordance with Islam’s theory56, a ∆Ginj value exceeding 0.8 eV and a ∆Greg value exceeding 0.5 eV are capable of facilitating rapid electron injection and regeneration. Consequently, the dyes employed in this study, including HJ19 and HJ20, exhibited a sufficient driving force to guarantee the injection of electrons into the semiconductor and their injection by the redox electrode.

A comprehensive analysis of these data revealed that HJ19 and HJ20 were the most promising candidates for use in D-π-A-π-A systems for efficient dye-sensitized solar cells. These compounds exhibited the greatest absorption in long-wavelength sunlight, the longest first-excited lifetime, and the largest short-circuit current density and open-circuit voltage.

TDM analysis

The TDM yielded a substantial amount of data pertaining to the electron jump characteristics of the dye molecules during the excitation process. To guarantee the veracity of the findings, the examination of the TDM was confined to coefficients with absolute values exceeding 10− 4. In this investigation, the fragment TDM was employed as the analytical tool. The YZ1 molecule was subdivided into three fragments for analysis in the TDM, comprising a donor fragment (Fragment 1), a π fragment (Fragment 2) and an acceptor fragment (Fragment 3). The remaining dyes, HJ2, HJ8 and HJ14–HJ23, were found to comprise five fragments. Additionally, the D1 fragment (Fragment 1), π1 fragment (Fragment 2), A1 fragment (Fragment 3), π2 fragment (Fragment 4) and A2 or A3 fragment (Fragment 5) were also considered. The data for YZ1, HJ2 and HJ8 were derived from a previous calculation17. Further details regarding the fragmentation process can be found in the supporting information.

Figure 6 presents a heatmap of the S0→S1 fragment transition matrix for HJ2, HJ8, H14–H16 and HJ19–HJ21, which were selected as representative photosensitizers owing to their predominant structural modifications. The Supporting Information also includes heatmaps displaying the TDM properties of other dyes (Figs. S3, S4). The heatmap of fCDT-based HJ2 revealed a multitude of nondiagonal elements with notable values, exemplified by nondiagonal fragment 1/fragment 3 (in green) and fragment 4/fragment 3 (in green). This suggests that electron transfer in the D1 motif, A1 motif and π2 motif of the D-π-A-π-A molecule is a pivotal factor in determining its optoelectronic properties17. In the case of the dye molecules HJ14 and HJ15 with BTD and difluorosubstituted BTD, the values of the off-diagonal elements were insignificant relative to those of the diagonal elements. Furthermore, fragment 1 (ullazine electron-rich group) had the largest value in red. The leaps were predominantly local excitations, concentrating the Ullazine electron-rich group. The diagonal elements of the 1,3 fragments of HJ14 and HJ15, as well as those of fragments 3 and 1, were light blue, indicating that the electron transfer from fragment 1 (ullazine electron-rich motif) to fragment 3 (BTD and difluorinated BTD) also made a minor contribution. Nevertheless, the expansion of the conjugation space of the BTD introduced a more complex electron-leaping situation. In HJ16, which contained conjugated substituted BTD electron acceptor motifs, the anomalies between the nondiagonal elements 1,3 and 1,4 became more pronounced and were unfavorable for the overall photovoltaic performance, with the exception of fragment 1 (red) and fragment 3 (green), which presented larger values. Replacing the carboxyl group at position A2 with a CSSH group resulted in thermogram images for HJ19 and HJ20 that were similar to those of HJ14 and HJ15. Fragment 1 (ullazine electron-rich group) retained its largest value in red. However, the values of the diagonal meta-fragment 4 and the nondiagonal meta-fragment 1 slightly increased, indicating that the contribution to the electron transfer of fragment 1→fragment 4 was increased because of the effect of the CSSH group. This finding aligns with the outcomes presented in Table 2 and the analytical results depicted in Fig. 6. The results are consistent.

Conclusion

In this study, we designed ten D-π-A1-π-A2 dye-sensitive molecules (HJ14–HJ23) on the basis of the acceptors of BTD and its derivatives at the A1 position and the CSSH groups at the A2 position. We then proceeded to investigate the effects of the acceptors on their photovoltaic properties via DFT and TDDFT calculations. First, following the replacement of the electron acceptor group at the A1 position with HJ2, the dye molecule retained a nonplanar structure. This structure helps prevent spontaneous aggregation of the dye molecule and improves its stability. Following the replacement of the fCDT electron acceptor with the BTD electron acceptor, the LUMO energy level of the molecule was found to be significantly reduced. This resulted in a decrease in the HOMO-LUMO energy gap, which is favorable for the spectral redshift. Second, the dyes (e.g., HJ14 and HJ15) utilizing BTD and its fluorinated derivatives as the A1 moiety exhibited notable redshifted absorption spectra within the visible range, with a maximum absorption wavelength of 592 nm, which is 40 nm redshifted in comparison to that of the original dye, HJ2. Furthermore, these dyes demonstrated exceptional optoelectronic characteristics, exhibiting high maximum extinction coefficients and light-trapping efficiencies. Moreover, the electron injection drive and regeneration drive of the dye molecules exceeded the theoretical thresholds, indicating that these dye molecules possess sufficient electron injection and regeneration capabilities in DSSCs. In particular, dyes HJ19 and HJ20 are regarded as the most promising candidates for high-efficiency DSSCs, given their wider absorption range, longer excited state lifetime, and higher light capture efficiency. Ultimately, TDDFT orbital analysis and TDM analysis demonstrated that the primary contribution of the dye molecule to the S0→S1 transition is derived from the HOMO→LUMO transition. Despite the reduction in the proportion of the HOMO→LUMO contribution following the introduction of BTD and its derivatives, it still occupies a dominant position. This finding indicates that the incorporation of the BTD moiety did not alter the primary electron-leaping mechanism of the YZ7 dye molecule.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its Supplementary Information files.

References

Hagfeldt, A., Boschloo, G., Sun, L., Kloo, L. & Pettersson, H. Dye-sensitized solar cells. Chem. Rev. 110, 6595–6663 (2010).

Yuan, M. et al. Molecular electronics: from nanostructure assembly to device integration. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 7885–7904 (2024).

Saud, P. S. et al. Dye-sensitized solar cells: fundamentals, recent progress, and Optoelectrical properties improvement strategies. Opt. Mater. 150, 115242 (2024).

Muñoz-García, A. B. et al. Dye-sensitized solar cells strike back. Chem. Soc. Rev. 50, 12450–12550 (2021).

Mahajan, U., Prajapat, K., Dhonde, M., Sahu, K. & Shirage, P. M. Natural dyes for dye-sensitized solar cells (DSSCs): an overview of extraction, characterization and performance. Nano-Struct. Nano-Objects 37, 101111 (2024).

Regan, B. O. & Gratzelt, M. A low-cost, high-efficiency solar cell based on dye-sensitized colloidal TiO2 films. Nature 353, 737–740 (1991).

Ren, Y. et al. Hydroxamic acid pre-adsorption raises the efficiency of cosensitized solar cells. Nature 613, 60–65 (2023).

Mahmood, A. et al. A novel thiazole based acceptor for fullerene-free organic solar cells. Dyes Pigm. 149, 470–474 (2018).

Mahmood, A. & Wang, J. A time and resource efficient machine learning assisted design of non-fullerene small molecule acceptors for P3HT-based organic solar cells and green solvent selection. J. Mater. Chem. A 9, 15684–15695 (2021).

Mahmood, A., Irfan, A. & Wang, J. L. Machine learning and molecular dynamics simulation-assisted evolutionary design and discovery pipeline to screen efficient small molecule acceptors for PTB7-Th-based organic solar cells with over 15% efficiency. J. Mater. Chem. A 10, 4170–4180 (2022).

Jiang, S., Chen, Y., Li, Y. & Han, L. Novel D-D-π-A indoline-linked coumarin sensitizers for dye-sensitized solar cells. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A 384, 112031 (2019).

Yu, X. et al. A new D–D–π–A dye for efficient dye-sensitized solar cells. J. Energy Chem. 25, 769–774 (2016).

Wang, T. et al. D-A-π-A carbazole dyes bearing fluorenone acceptor for dye sensitized solar cells. J. Mol. Struct. 1226, 129367 (2021).

Kang, X. et al. El-Sayed effect of molecular structure perturbations on the performance of the D–A – π–A dye sensitized solar cells. Chem. Mater. 26, 4486–4493 (2014).

Wubie, G. Z. et al. Structural engineering of organic D–A–π–A dyes incorporated with a dibutyl-fluorene moiety for high-performance dye-sensitized solar cells. ACS Appl. Mater. 13, 23513–23522 (2021).

Islam, M. A., Eletmany, M. R. & El-Shafei, A. Exploring the impact of electron acceptor tuning in D-π-A′-π-A photosensitizers on the photovoltaic performance of acridine-based DSSCs: a DFT/TDDFT perspective. Mater. Today Commun. 35, 106170 (2023).

Huang, J., Yang, L., Chen, Z., Zhou, Y. & Zeng, S. DFT/TDDFT in silico design of ullazine-derived D–π–A–π–A dye photosensitiser. New. J. Chem. 47, 11030–11039 (2023).

Zhang, Y. et al. Theoretical study of D–A′–π–A/D–π–A′–π–A triphenylamine and quinoline derivatives as sensitizers for dye-sensitized solar cells. RSC Adv. 10, 17255–17265 (2020).

Wang, M. et al. Synthesis of D-π-A-π-D type dopant-free hole transporting materials and application in inverted Perovskite solar cells. Acta Chim. Sin. 77, 741–750 (2019).

Delcamp, J. H., Yella, A., Holcombe, T. W., Nazeeruddin, M. K. & Grätzel, M. The molecular engineering of organic sensitizers for solar-cell applications. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52, 376–380 (2013).

Ma, W., Jiao, Y. & Meng, S. Predicting energy conversion efficiency of dye solar cells from first principles. J. Phys. Chem. C 118, 16447–16457 (2014).

Zhang, Y. et al. Ullazine donor–π bridge-acceptor organic dyes for dye-sensitized solar cells. Chem. Eur. J. 24, 5939–5949 (2018).

Tian, H. et al. Phenothiazine derivatives for efficient organic dye-sensitized solar cells. Chem. Commun., 3741–3743 (2007).

Heredia, D. et al. Spirobifluorene-bridged donor/acceptor dye for organic dye-sensitized solar cells. Org. Lett. 12, 12 (2010).

Tian, H. et al. Effect of different dye baths and dye-structures on the performance of dye-sensitized solar cells based on triphenylamine dyes. J. Phys. Chem. C 112, 11023 (2008).

Nachimuthu, S., Chen, W., Leggesse, E. G. & Jiang, J. First principles study of organic sensitizers for dye sensitized solar cells: effects of anchoring groups on optoelectronic properties and dye aggregation. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 18, 1071–1081 (2016).

Bei, Q. et al. Benzothiadiazole-based materials for organic solar cells. Chin. Chem. Lett. 35, 108438 (2024).

Wang, C. et al. Benzothiadiazole-based conjugated polymers for organic solar cells. Chin. J. Polym. Sci. 39, 525–536 (2021).

Neto, B. A. D., Correa, J. R. & Spencer, J. Fluorescent benzothiadiazole derivatives as fluorescence imaging dyes: a decade of new generation probes. Chemistry 28, e202103262 (2022).

Pradhan, A. K., Ray, M., Parthasarathy, V. & Mishra, A. K. Effects of donor and acceptor substituents on the photophysics of 4-ethynyl-2,1,3-benzothiadiazole derivatives. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 25, 29327–29340 (2023).

Surendra, B. N., Kuot, M. M. P. & Abubakari, I. DFT and TD-DFT studies of D-π-A organic dye molecules with different spacers for highly efficient reliable dye sensitized solar cells. ChemistryOpen 13, e202300307 (2024).

Kontkanen, O. V., Hukka, T. I. & Rantala, T. T. Electronic structures of three anchors of triphenylamine on a p-type nickel oxide(100) surface: density functional theory with periodic models. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 26, 17588–17598 (2024).

Kargeti, A., Dhar, R. S., Siddiqui, S. A. & Saleh, N. Design and exploration by quantum chemical analysis of photosensitizers having D-π-π-A.- and D-D-triad-A.-type molecular structure models for DSSC. ACS Omega 9, 11471–11477 (2024).

Sharma, S. J. & Sekar, N. A promising small-sized near-infrared absorbing zwitterionic dye for DSSC and NLO applications: DFT and TD-DFT approaches. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 25, 30023–30039 (2023).

Sanusi, K., Fatomi, N. O., Aderogba, A. A., Khoza, P. B. & Igumbor, E. A DFT study of solvent and substituent effects on the adsorptive and photovoltaic properties of some selected porphyrin derivatives for DSSC application. J. Fluoresc. 34, 2513–2522 (2024).

Elmorsy, M. R. et al. Design, synthesis, and performance evaluation of TiO2-dye sensitized solar cells using 2,2’-bithiophene-based co-sensitizers. Sci. Rep. 13, 13825 (2023).

Islam, F. et al. Anthracene-bridged sensitizers for environmentally compatible dye-sensitized solar cells: in silico modelling and prediction. J. Mol. Graph Model. 108496 (2023).

Britel, O., Fitri, A., Benjelloun, A. T., Benzakour, M. & Mcharfi, M. Carbazole based D-πi-π-A dyes for DSSC applications: DFT/TDDFT study of the influence of πi-spacers on the photovoltaic performance. Chem. Phys. 565, 111738 (2023).

Conradie, M. M. UV-Vis spectroscopy, electrochemical and DFT study of tris(β-diketonato)iron(III) complexes with application in DSSC: role of aromatic thienyl groups. Molecules 27, 3743 (2022).

Frisch, M. J. et al. Gaussian 16, Revision C.01 (Gaussian, Inc., 2016).

Tomasi, J., Mennucci, B. & Cancès, E. The IEF version of the PCM solvation method: an overview of a new method addressed to study molecular solutes at the QM ab initio level. J. Mol. Struct. (Theochem.) 464, 211–226 (1999).

Iozzi, M. F., Mennucci, B., Tomasi, J. & Cammi, R. Excitation energy transfer (EET) between molecules in condensed matter: a novel application of the polarizable continuum model (PCM). J. Chem. Phys. 120, 7029 (2004).

Yanai, T., Tew, D. & Handy, N. A new hybrid exchange–correlation functional using the Coulomb-attenuating method (CAM-B3LYP). Chem. Phys. Lett. 393, 51–57 (2004).

Lu, T., Chen, F. & Multiwfn A multifunctional wavefunction analyzer. J. Comput. Chem. 33, 580–592 (2012).

Chattopadhyay, D., Lastella, S., Kim, S. & Papadimitrakopoulos, F. Length separation of zwitterion-functionalized single wall carbon nanotubes by GPC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 124, 728–729 (2002).

Chen, S. L., Yang, L. N. & Li, Z. S. How to design more efficient organic dyes for dye-sensitized solar cells? Adding more sp2-hybridized nitrogen in the triphenylamine donor. J. Power Sources 223, 86–93 (2013).

Peach, M. J. G., Benfield, P., Helgaker, T. & Tozer, D. J. Excitation energies in density functional theory: an evaluation and a diagnostic test. J. Chem. Phys. 128, 044118 (2008).

Wei, S. et al. Theoretical insight into electronic structure and optoelectronic properties of heteroleptic cu(I)-based complexes for dye-sensitized solar cells. Mater. Chem. Phys. 173, 139–145 (2016).

Barone, V. & Cossi, M. Quantum calculation of molecular energies and energy gradients in solution by a conductor solvent model. J. Phys. Chem. A 102, 1995–2001 (1998).

Bai, Y. et al. Engineering organic sensitizers for iodine-free dye-sensitized solar cells: Red-shifted current response concomitant with attenuated charge recombination. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 11442–11445 (2011).

Soroush, M. & Lau, K. K. S. Insights into dye-sensitized solar cells from macroscopic-scale first-principles mathematical modeling. In Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells: Mathematical Modelling and Materials Design and Optimization (eds Soroush, M. & Lau K. K. S.) 83–119 (Academic, 2019).

Li, M. et al. Theoretical study of WS-9-based organic sensitizers for unusual Vis/NIR absorption and highly efficient dye-sensitized solar cells. J. Phys. Chem. C 119, 9782–9790 (2015).

Marinado, T. et al. How the nature of triphenylamine-polyene dyes in dye-sensitized solar cells affects the open-circuit voltage and electron lifetimes. Langmuir 26, 2592–2598 (2010).

Li, W. et al. What makes hydroxamate a promising anchoring group in dye-sensitized solar cells? Insights from theoretical investigation. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 5, 3992–3999 (2014).

Gu, Q. et al. Excited-state lifetime modulation by twisted and tilted molecular design in carbene-metal-amide photoemitters. Chem. Mater. 34, 7526–7542 (2022).

Islam, A., Sugihara, H. & Arakawa, H. Molecular design of ruthenium(II) polypyridyl photosensitizers for efficient nanocrystalline TiO2 solar cells. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A 158, 131–138 (2003).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the Fujian Provincial Science and Technology Economic Integration Platform (FJKX-2024XRH08), the Education and Research Project of Young and Middle-aged Teachers of Fujian Province (JAT220303), Fujian Provincial Technological Innovation Key Research and Industrialisation Projects (2023G019), Science and Technology Plan Project of Putian (2023GJGZ001, 2023GZ2001PTXY21), National Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training Program for College Students (202411498001X), Startup Fund for Advanced Talents of Putian University (2024042).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Jing Huang: supervision, data curation, funding acquisition and writing-original draft; Zihao Li: investigation and funding acquisition; Lei Yang: funding acquisition, visualization and writing-review & editing; Rongfang Hu: methodology and formal analysis; Guoyu Shi: Writing-review & editing. All authors finally reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Huang, J., Li, Z., Yang, L. et al. A comprehensive DFT/TDDFT investigation into the influence of electron acceptors on the photophysical properties of ullazine-based D-π-A-π-A photosensitizers. Sci Rep 15, 3101 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87189-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87189-z