Abstract

A new modified approach was used to synthesize hydroxyapatite-carbon nanocomposite (HAP-C) by utilizing cement kiln dust (CKD), which is an industrial waste product, as a source of calcium. Calcium from CKD was first chelated using citric acid, and the chelate was transformed into calcium carbonate and carbon by calcination at 450 °C for 1 h, then reacted with ortho-phosphoric acid using a precipitation method, thus serving as a precursor for the formation of HAP-C. Then, HAP-C was calcined at various temperatures for 2 h after it reached the desired temperature at a heating rate of 10 °C/min. By characterizing the adsorbent, the composite was mesoporous, with a negatively charged surface at the operating pH, and an average diameter and length of 10 ± 3.6 nm and 8 ± 2.9 nm, respectively. Quantile regression analysis showed that the removal varies directly with time and dose, and inversely with initial concentration. Removal efficiency reached about 95% and about 80% at 10 ppm initial concentration, 10 min contact time, and a dose of 3.8 g/L, at pH 7 for RB and pH 4 for LV, respectively. Adsorption isotherms followed Sips model as inferred from linear and non-linear regression analysis. Adopting this novel approach in synthesizing HAP-C using a single precursor and a waste raw material reduces the environmental impact and incurred costs associated with the conventional synthesis route, while following the principles of circular economy in converting wastes to value-added products.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Due to its wide applications as a binding material in various fields of construction, cement is one of the frequently used man-made products. In the due process of its production, a significantly huge amount of cement kiln dust (CKD) by-product is generated. For every ton of cement produced, an estimated average of 54 to 200 Kg of CKD is formed1. The world annual production of cement in 2020 was 4.1 billion tons, which would thus produce 221.4 to 820 million tons of CKD worldwide1,2. The production of CKD is mainly attributed to the need of producing a low alkali product (i.e., cement) from raw materials with high alkali content3. The presence of high alkali contents in the CKD renders it unsuitable for recycling. The high temperature in the kiln can volatilize alkalis, which would ultimately condense in the cyclone preheaters and cause clogging of the cyclones leading to frequent disruption of the process1,3. Hence, CKD usually ends up in open landfills, resulting in many adverse health problems to humans along with other environmental issues. There are two main reasons for the health hazards associated with CKD; its high alkali content and extremely small particle size which is considered to be within the respirable range4,5. Among these hazards are lung cancer, stomach cancer, colon cancer, silicosis, bronchitis, bronchial asthma, and pulmonary inflammation4,5. Considering these hazards and the difficulty of CKD recycling, there is an urgent need for finding adequate disposal/reuse procedures.

To reduce the hazardous effect of CKD on humans and the environment, many attempts have been made to utilize CKD in other purposeful applications. In one of these attempts, CKD has been utilized as a source of mineral nutrients such as Mg, S, and K in the agricultural field6. However, this approach is not encouraged due to the possible presence of toxic substances within the CKD, like free chlorides. CKD has also been applied in soil stabilization, where it was added to the soil in different proportions to fill the voids and enhance the soil mechanics6. Raw CKD has also been used either separately or added with other wastes, like fly ash and polystyrene, as a replacement of cement in concrete7. The production of ceramic tiles and cement based bricks using CKD was also investigated7. The use of CKD was also extended to include water and wastewater treatment, particularly in adjusting the pH of acidic water due to its high CaO content, as well as in the removal of different types of heavy metals7,8. The use of CKD in sequestering CO2 has also been reported in literature9. Even though these attempts were beneficial in mitigating the negative impact of CKD, they were insufficient given the tremendous amount of CKD produced daily.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report to utilize CKD waste for the synthesis of HAP or HAP-C as a value-added product. The synthesis of the nanocomposite is conducted in a novel approach, in which a single calcium chelate precursor incorporating both carbon and calcium is utilized. In previous literature, two precursors were used: one for carbon and one for calcium. The main advantage of the proposed approach is reducing the number of steps required for synthesizing the composite since its carbon constituent is obtained in-situ by thermal degradation of the calcium chelate precursor, while the degradation products (CaCO3 + C) are utilized for HAP-C synthesis. Adopting this approach would consequently reduce the cost and environmental impact of the conventional synthesis process of such composites which uses two precursors and an external source for carbon and does not rely on wastes as a raw material. Compared to other processes for industrial waste derived adsorbents, this process is more environmentally friendly and involves less complicated steps. For instance, in the work by Ibrahim and co-workers, zeolite was produced from sulfuric acid residue via several complicated steps to separate quartz from kaolinite and obtain the required silica/alumina ratio which was not inherently present in the original waste10. They also utilized precursor chemicals in addition to the waste which consequently increases the cost of the final product. Furthermore, in the due process of producing their adsorbent they used harsh chemicals such as sodium hydroxide. The proposed synthesis approach and its application in water treatment follows the UN sustainable development goals (SDGs # 6 and 12), making it more advantageous than other processes.

In this work, we aim at developing an adsorption process for the removal of the dye rhodamine B (RB) and the drug levofloxacin (LV) efficiently from water using a composite adsorbent synthesized from CKD. The work is divided into two parts; the first part is dedicated to the exploitation of CKD as a precursor to synthesize a nanocomposite consisting of hydroxyapatite and carbon (HAP-C), in the due process HAP-C is characterized by Fourier Transform Infra-Red Spectroscopy (FTIR), Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET), X-Ray diffraction (XRD), Transmission Emission Microscopy (TEM), Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA), and zeta potential measurements. The second part is aimed at evaluating the performance of the synthesized nanocomposite in the single and binary removal of the contaminants in question. The operating parameters influencing the adsorption are determined by non-parametric quantile regression. Adsorbent performance is also evaluated by conducting adsorption isotherm, kinetics, and thermodynamic studies, while the adsorption mechanism is explained in view of these studies.

Materials and methods

Materials

All chemicals purchased were of analytical grade and were used as received without any further purification. For the process of synthesis of nano-hydroxyapatite/carbon composite (HAP-C) from CKD, citric acid monohydrate (MW 210.14 g/mol, purity 99.5%) was purchased from Chem-Lab NV (Belgium) and ortho-phosphoric acid 85% was obtained from Merck Millipore (Switzerland). The CKD of about 74 microns average particle diameter and 2.5 specific gravity (ASTM-C188-95)8 was collected from a local cement industry and its composition was determined by XRF (Table S1). For the sorption studies, the following chemicals were used; Rhodamine-b dye (pKa=3.7, MW 479.02 g/mol) from Loba Chemie (India), sodium hydroxide (MW 40 g/mol, purity 99%) and hydrochloric acid (purity 37% by wt) from Piochem labs. Levofloxacin hemihydrate (pKa1=6.8 and pKa2=8.2, MW 740.7 g/mol, purity 98.0-102%) was obtained from Zhejiang East Asia pharmaceutical Co. (China), while commercial hydroxyapatite (MW 1004.6 g/mol) was purchased from Nano Tech Egypt for Photo-Electronics.

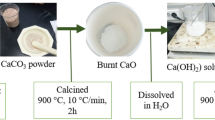

Separation of calcium

To chelate calcium and separate it from other components of the CKD, citric acid monohydrate was first reacted with the raw CKD. The procedure adopted by Zhao et al., 2013 was modified, where the CKD was initially subjected to drying and removal of volatile matter at 105 °C ± 2 °C for 7 h in an oven, i.e., until the mass of the sample was stable11. Then, 1 M citric acid was slowly added to 10 g of CKD in a 250 mL Erlenmeyer flask, to avoid effervescence caused by evolving hydrogen gas11. To prevent formation of sludge at the end of the reaction and enhance mixing of CKD, a solid to liquid ratio of 1:20 w/v was adopted from literature1. The reaction was conducted at 25 °C ± 2 for 10 min on a magnetic stirrer with vigorous mixing. The calcium rich solution formed11, was separated from unreacted CKD using a vacuum filter, then the solution was heated for 1 h at 105 °C ± 2. The result was a white calcium chelate that was subjected to five times washing with distilled water followed by vacuum filtration. Then, the white precipitate was dried in an oven for 2 h at 100 °C ± 2. Figure 1a illustrates the process of separating calcium from CKD.

The method adopted herein is a modification to the one adopted in previous literature for separating calcium from wollastonite. For precipitation of calcium, heating is used here while in previous work the calcium rich solution was reacted with potassium carbonate11. Unlike the previous method, the solid to liquid ratio was taken into consideration. The reason behind this modification is to improve the purity of the eluate since CKD, unlike wollastonite, is composed of many metals other than calcium, leading to the possibility of precipitation of metal carbonates other than CaCO3 if the procedure was adopted with no modification.

It is worth noting that in the due process of chelating calcium from the CKD, the alkalis also dissolve in the citric acid, hence, the unreacted CKD becomes free of alkalis. This makes it feasible to use, after simple drying, in any ceramic products as a raw material, such as glass, tiles, or cement. Reusing the unreacted materials adds more sustainable aspects to the process and renders it more suitable for scaling-up. However, further pilot experiments and feasibility studies involving cost-benefit analysis are needed to up-scale the process to the industrial level.

Synthesis of HAP-C nanocomposite

HAP synthesis method by Pham Minh et al., 2013 was adopted with modification to synthesize the HAP-C nanocomposite instead of HAP12. Initially, calcium chelate prepared earlier was subjected to thermal decomposition at 450 °C for 1 h in a muffle furnace (VULCAN 3-550). The product of thermal decomposition was a mixture of calcium carbonate and carbon. The latter was intentionally left in the mixture to be utilized in the synthesis of the HAP-C nanocomposite. The synthesis took place as follows. First, calcium carbonate (in the presence of the carbon) and ortho-phosphoric acid were reacted in stoichiometric ratios to obtain a 1.67 Ca/P ratio. The reaction took place for 24 h at 80 °C ± 5 on a magnetic stirrer with vigorous stirring. The o-H3PO4 was added to the solution of calcium carbonate dropwise (~ 1.5 mL/min). Vacuum filtration was used to separate resultant product from the supernatant, then the product was washed with distilled water for 5 to 6 times, followed by air drying for 12 h. XRD patterns for CKD and thermally treated calcium chelate are given in Fig. S1 of SI. Figure 1b illustrates the process of synthesis of HAP-C nanocomposite.

The synthesized HAP-C was subjected to various thermal heating scenarios to assess the effect of heat on its properties and adsorption performance, as summarized in Table 1. Heating HAP-C at 400 °C, 500 °C, and 700 °C under inert conditions produces HAP-C 400 A, HAP-C 500 A, and HAP-C 700 A, respectively. Under thermal treatments in the presence of air, the HAP-C converts to HAP (HAP 700, and HAP 900).

Characterization

FTIR analysis was conducted using a Thermo-Scientific NICOLET 380 (USA) FTIR device. The scan range was from 400 to 4000 cm− 1 with an average recording of 32 scans. The crystallinity of HAP and HAP-C was analyzed using powder x-ray diffractometer BRUKER D8 system (USA). The 2θ scan ranged from 5° to 80° at an increment rate of 0.03° per second. The surface area, average pore diameter, and average pore volume of the as-synthesized materials were determined using Micrometrics ASAP 2020 instrument (USA). The adsorption/desorption isotherms (at −196° C) were generated using nitrogen gas. Then, the specific surface area was calculated by Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) and Langmuir methods, while the pore volume was estimated based on Barret-Joyner-Halenda (BJH) model.

The morphology and sizes of the as-synthesized materials were examined using a high-resolution transmission electron microscope (HR-TEM, JOEL JEM-2100, Japan). Initially, the samples were dispersed in distilled water and sonicated for 5 min, then vacuum filtered and dried. Afterward, they were subjected to a beam of electrons at 200 kV to determine the morphologies, average sizes, and lattice planes. The thermal stability of the synthesized samples was examined by a LABTRON thermal analyzer (UK), where 20 mg sample powder in a ceramic cuvette was subjected to 1000 °C at a heating rate of 10 °C per min. Then, the thermal profiles of the samples were generated. The surface charge of the adsorbents was measured using Malvern Zeta-sizer (UK). The procedure was as follows; 10 mg of the adsorbent were dissolved in 50 mL distilled water and sonicated for 10 min. Then, the solution was distributed equally over five beakers where the pH was adjusted using either HCl or NaOH.

Thermo Scientific ICP-AES 7000 (USA) was used to determine the concentrations of calcium ions leached from CKD. Percent extraction of Ca2+ was calculated using the following formula,

where Cion is the concentration of calcium as quantified by ICP in mg/L, V is the volume of the solution, MCKD is the mass of the CKD sample, and Xion CKD is the mass fraction of calcium ion present in the CKD.

Adsorption experiments

Batch adsorption experiments were performed on a rotary shaker at 80 rpm. To study the effect of pH, an adsorbent dose of 3.8 g/L was applied on 25 ppm RB or LV at a pH range of 3–10 for a time of 3.5 h. Time profiles were measured at initial concentrations of 10, 15, 25, and 50 ppm using 3.8 g/L adsorbent dose at pH 7 for RB and pH 4 for LV. The effect of initial concentration was studied in the range of 10–100 ppm at an adsorbent dose of 3.8 g/L at the same pHs applied in the time profiles and for 3.5 h contact time. The effect of adsorbent dose was examined in the range of 1–7 g/L on initial concentrations of 10, 15, 25, and 50 ppm for a contact time of 3.5 h. Regarding the effect of temperature, it was investigated at an initial concentration of 25 ppm and adsorbent dose of 3.8 g/L after 3.5 h. After adsorption, contaminant solutions were centrifuged two to three times at 12,000 rpm for 5 min (SIGMA 3-30KS, Germany) to remove the adsorbent and the supernatant was measured on a UV-spectrophotometer (PG instruments T80 + UV/VIS spectrophotometer, UK) at 554 and 288 nm for RB and LV, respectively, then the absorbances were converted to their corresponding concentrations using a pre-prepared calibration curve. Percent removal and equilibrium adsorption capacities were calculated based on Eq. S1 and S2 of SI, respectively13,14. The time profiles at 10 ppm were fitted to the pseudo-first and pseudo-second order models (Eqs. S3, S4 in SI, respectively) and the relevant kinetic parameters were determined14,15. Besides, equilibrium adsorption isotherm models of Langmuir, Freundlich, Sips, and D-R were applied to describe the adsorption behavior (Eqs. S5–S9, SI)16,17,18,19. The study of the effect of temperature was performed in the range of 30–80 ℃ at an initial concentration of 25 ppm and 3.8 g/L adsorbent dose using pH 7 for RB and pH 4 for LV. The thermodynamic parameters were obtained using the van’t Hoff equation (Eq. S10 and S11, SI)20. Also, binary systems of RB and LV were studied at 10 ppm initial concentration for each contaminant at pH 7 and adsorbent dose of 3.8 g/L after 3.5 h. Amplitudes of LV were determined based on first-order derivative UV-spectroscopy at 298 nm where concentrations were determined from a calibration curve while for RB, absorbances from UV spectrum were taken without manipulation at 554 nm and concentration was also determined based on a calibration curve. The UV-spectrum plots of zero and first order derivatives of RB and LV are given in Fig. S14 of SI. Similarly, the single and binary systems were prepared in tap water at the same conditions and the removal efficiency was calculated.

Regeneration study was performed after adsorption of 10 ppm RB or LV on 3.8 g/L adsorbent at pH 7 and 4, respectively, for 15 min. Desorption was undertaken using ethanol absolute as a desorbing agent for 30 min and adsorption-desorption was performed for 4 cycles.

Statistical analysis

All measurements were performed in triplicates and the respective means and standard deviations for percent removal and adsorption capacity were calculated. A two-tailed student’s t-test was performed at a 95% level of confidence to test the significance of results. Linear regression analysis was also performed on the adsorption isotherms and kinetic profiles and the coefficient of determination (R2), the chi-square (X2), and RMSE values were calculated. This linear regression analysis was conducted on Origin-lab software, version 85E. In addition, non-linear regression analysis using R studio software 2021.09.02 (USA) was conducted for the adsorption isotherms to identify the best fitting model. To determine the effect of different operating conditions on the removal efficiency, non-parametric quantile regression was performed using R studio software. Quantile regression is a non-parametric statistical model designed to understand the relationship between independent variables and targeted percentiles of a dependent variable. It diverges from the traditional linear regression, which solely estimates average effects, by offering insights into the conditional median or other quantiles, making it especially useful when dealing with data that deviate from normality.

The mathematical representation of the quantile regression model is:

Where QY (T|X) denotes the τ-th quantile of the dependent variable Y given the predictors X, and β(τ) represents the vector of quantile-specific coefficients.

The coefficients in quantile regression are estimated by minimizing the sum of the weighted absolute differences between observed values and the fitted quantiles. These coefficients inform about the expected change in the τ-th quantile of the response variable for a one-unit change in the predictor variable, holding other variables constant.

In this study, we have 24 observations across one dependent variable (Y) which denotes % removal of LV and three independent variables (X1, X2, and X3) which denote adsorbent dose, time, and initial concentration, respectively. The same setting applies for the second data set for RB where (Y) denotes the % removal of RB, while X1, X2, and X3 refer to adsorbent dose, time, and initial concentration, respectively.

Results and discussion

Synthesis process for HAP and HAP-C nanocomposites

Citric acid readily forms a complex with calcium via chelation21. The reaction between citric acid, which is a triprotic acid, and the CKD is given by the following chemical equation,

where M is calcium metal, L is the citrate ligand and H+ is the hydrogen ion lost from the carboxylic acid functional group11. The number of hydrogen ions lost determines the type of chelate formed, Table S2 of SI illustrates the types of chelates formed and their corresponding stability constants. Based on the values of the stability constants, it can be deduced that the mono calcium chelate is the most dominant type of chelate formed since it possesses the highest stability among other chelates.

Effect of pH and citric acid concentration on calcium ions extraction yield was studied (Table S3, SI), and accordingly the optimal concentration of citric acid to obtain Ca2+ ion was chosen to be 1 M and was applied at an optimal pH 3 without pH adjustment to avoid contamination with pH adjusting reagents.

Thermal gravimetric analysis was conducted on the calcium chelate complex prior to and after heat treatment. Figure 2a depicts the decomposition stages of the calcium chelate complex. Stage I represents the loss of adsorbed water molecules on the surface, which accounts for 1.6% of the weight lost. In stage II, no loss in weight is observed due to melting of the chelate22. In stage III, the chelate starts to decompose with a loss of carbon in the form of CO2 starting from around 300 °C. The decomposition is completed at 560 °C and accounts for 39% loss in weight after which no weight loss takes place, i.e., only CaCO3 exists. Stage III can be represented by the following chemical equation (unbalanced).

Stage IV is associated with no loss of weight and no decomposition, while stage V begins at 681 °C, where the calcium carbonate decomposes to calcium oxide and CO2.

Figure 2b illustrates the TGA profile of the chelate complex after heat treatment at 450 °C for 1 h. The profile is similar to its counterpart conducted before heat treatment with the exception of the amount of weight loss. In stage III, the decomposition starts at a temperature above 400 °C which is higher than its counterpart for the untreated chelate, while the weight loss is less than its counterpart for the untreated chelate (Fig. 2a) due to prior heat treatment and calcination. This indicates the presence of carbon in the treated sample. In stage IV, CaCO3 is formed; whereas in stage V, the decomposition of CaCO3 to CaO is almost complete yielding a weight loss of about 40%, which is close to the theoretical weight loss (i.e., 44%) typically obtained for the decomposition of pure CaCO3 to CaO. XRD analysis was also performed to confirm the formation of CaCO3 after heat treatment (Fig. S1, SI).

The carbon from citric acid, which chelated the calcium ion, was not completely removed during calcination and this was done on purpose to exploit this carbon in synthesizing HAP-C. The presence of this carbon imparted a brownish black color to the CaCO3 which naturally appears white in color. This color change is owed to carbon coating of the CaCO3. A free heat activation protocol was adopted from previous literature to activate carbon in HAP-C without use of chemical reagents. This approach was deployed to enhance the adsorption performance of HAP-C nanocomposite via increasing the porosity and activating the hydroxyl groups23,24. Zhou et al., 2012, reported that the surface area of the carbon exceeded the 700 m2/g24, however, this is not the case with HAP-C due to the presence of HAP and the increased heat treatment of HAP which led to increase in the size of HAP crystals and consequent decrease in surface area25,26. Meanwhile, the activation protocol still enhanced the adsorption performance of HAP-C toward removing RB and LV, as shown in Table S4 of SI. Adsorbent HAP-C 700 A showed the highest removal efficiency, and thus is chosen as the optimal adsorbent for the complete adsorption study.

Characteristics of the as-synthesized materials

FTIR spectra for all synthesized HAP, HAP-C nanocomposites, and the commercial HAP (com-HAP) are presented in Fig. S2 in SI, while that pertaining to the chosen adsorbent HAP-C 700 A is depicted in Fig. 3a. All materials show a broad band at 3700 –3200 cm− 1 which corresponds to the stretching vibration of hydrogen bonded group. Peaks appearing at 563, 960, and 1030 cm− 1 can be attributed to the stretching vibration of PO43−. The bending vibration of PO43− bonds is represented by the peaks at 605, 871, and 2360 cm− 1, however, the latter can only be observed in com-HAP, HAP 700, HAP-C, and HAP-C 400 A27. Peaks at 1458 and 1380 cm− 1 can be ascribed to the bending of the OH group28.

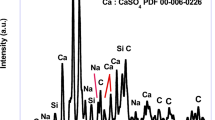

XRD patterns for all HAP and HAP-C compounds (Fig. S3, SI) along with that of HAP-C 700 A (Fig. 3b) show peaks at 26°, 29°, 32°, 34°, 40°, 46°, and 54° thus confirming the crystalline nature of these materials, as consistent with previous literature26,29,30. Table S5 illustrates the crystal sizes of the prepared materials, as estimated by Debye Scherrer equation, along with their BET surface areas. The largest crystal size was recorded for HAP 700 and HAP 900 (i.e., the pure samples), however they showed low surface area that can be attributed to their relatively large crystal size24. The other nanocomposites crystal sizes showed little variation, even though, their surface areas differed noticeably.

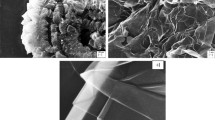

TEM image for HAP-C 700 A (Fig. 3c) reveals rod structured nanoparticles, which is a typical characteristic of nanohydroxyapatite31. As shown in the image, the nano rods are embedded into the body of the carbon which coats them. The mean sizes for the diameter and length of HAP-C 700 A nanorods are 10 ± 3.6 nm and 80.9 ± 28.9 nm, respectively. The mean diameter of HAP-C 700 A is more than three orders of magnitude less than that of the raw CKD. To investigate the effect of temperature on morphology, the TEM size distribution of HAP-C 700 A (Fig. S4a,b, SI) is compared to its HAP-400 A counterpart. The particle size distribution for HAP-400 A (Fig. S4c,d, SI) demonstrates a smaller mean diameter and length of 8.62 ± 2.97 nm and 72 ± 18.5 nm, respectively for the nanorods possibly due to mild sintering of HAP-C 700 A.

The BET isotherm for HAP-C 700 A presented in Fig. 3d is a type IV isotherm, associated with mesoporous pore sizes that range between 2 and 50 nm. The same type of isotherm is exhibited by all other as-synthesized materials (Fig. S5 a,b,c, SI). The shape of the hysteresis loop also indicates the geometry of the pores, which can be estimated to be cylindrical for HAP-C and HAP-C 400 A, while those of HAP-C 700 A and HAP-C 500 A almost agree with the wedge-shaped pore geometry (S. Lowell et al., 2004; Xu et al., 2020).

The estimated textural parameters are given in Table 2 which confirm that the average pore sizes of all materials exist in the mesoporous range. The BET and Langmuir surface areas show an inversely proportional relationship with the treatment temperature for all materials, and almost a directly proportional relationship with the pore volume and pore width for the nanocomposites only. The case for HAP 700 and HAP 900 is different, i.e., the pore width and pore volume decreased as temperature increased. This behavior can justify the poor adsorption performance of HAP 700 and HAP 900 since they possess the smallest surface areas and pore volumes amongst the synthesized adsorbents. The surface area diminishes with increasing heat treatment temperature due to the increase in the crystal size of HAP (Table S5, SI), in both pure and composite forms22. The pore width also plays a crucial role in the adsorption process. As clear from Table 2, the largest pore width is recorded for HAP-C 700 A, which showed the best removal efficiency for both contaminants (Table S4, SI). Regarding the elemental composition of the HAP-C 700 A, SEM-EDX revealed that it has a Ca/P ratio of about 1.66 which is close to the reported value (1.67) for hydroxyapatite32. The analysis confirms the presence of carbon along with the main constituents of hydroxyapatite.

Adsorption studies in a single-contaminant system

Since HAP-C 700 A showed enhanced adsorption performance over other as-synthesized materials by virtue of its increased pore width and pore volume, it was selected for further adsorption studies. The adsorbate solutions of RB and LV were analyzed before and after adsorption and UV/VIS scans (Fig. S6 of SI) showed lower intensity peaks after adsorption without the appearance of new peaks indicating that the contaminants were most likely captured by the adsorbent without producing any detectable by-products.

Effect of pH

Adsorption of each of RB (Fig. 4a) and LV (Fig. 4b) onto HAP-C 700 A was conducted under varying pHs. Percent removal of RB increased from pH 3 to 7 reaching about 96% then decreased again, while the percent removal of LV did not noticeably change and ranged between 75% at pH 4 and 66% at pH 10. In case of RB adsorption, lower percent removal was achieved in acidic pHs (< pH 7) due to the competition of H+ ions in solution with the positively charged RB on the active sites of the adsorbent33. The removal also declined under basic conditions (> pH 7) since xanthene groups and carboxylic groups on RB monomers interacted electrostatically to form dimers which ultimately led to an increase of the RB molecular size thus hindering its adsorption and diffusion into the pores of HAP-C 700 A34,35. In the pH range of 5–7, the highest removal efficiencies were attained. This can be explained in view of the surface charge of HAP-C 700 A which is negatively-charged (point of zero charge PZC = 3.9) as per its zeta potential (Fig. 4c), and that of RB which is zwitterionic as per its speciation diagram (pKa=3.7, www.chemicalize.com, accessed on March 1st, 2023), hence, they can possibly bind via van der Waals forces of dispersion or dipole-dipole interaction or possibly through hydrogen bonding. As for LV, the slightly higher removal efficiency observed at pHs 4 and 5 can be attributed to electrostatic interaction or van der Waals forces between the slightly negative to neutral HAP-C 700 A and the positively-charged LV at these specific pHs, as per LV speciation diagram (www.chemicalize.com, accessed on March 1st, 2023), in addition to possible hydrogen bonding. Since HAP-C 700 A recorded its highest removal for RB and LV at pH 7 and pH 4, respectively, these pH were chosen as the working pHs for further adsorption studies.

Time profiles and kinetics

The uptake profiles for the adsorption of RB and LV at various initial concentrations are shown in Fig. 5a,b, respectively. It can be inferred that the rate of removal increased with time then slowed down till it reached equilibrium after respective 10, 10, 120, and 180 min in case of 10, 15, 25, and 50 mg/L of RB and after respective 10, 30, 30, and 180 min in case of 10, 15, 25, and 50 mg/L of LV where complete saturation was attained. Also, qe increased from about 2.5 to 8.5 mg/g in case of RB and from about 2.2 to 9.5 mg/g in case of LV with increasing the initial concentration probably due to the increase in mass transfer36.

When applying pseudo-first and pseudo-second order kinetics on the time profiles at 10 ppm (Table 3, Figs. S7, S8 of SI), the pseudo-second order model showed a better fit for both RB and LV uptake profiles than its pseudo-first order counterpart owing to its higher R2 values, and hence qe values predicted by this model are comparable to the experimental ones. This is similar to a previously reported study on the adsorption of fluoxetine and famotidine drugs on xylan or pectin/activated charcoal magnetic nanocomposites37.

The pseudo-second order constants for adsorption of RB are almost twice those for LV adsorption, hence the rate of RB adsorption is double that of LV adsorption.

Equilibrium studies at different process parameters

By increasing the initial concentration of RB (Fig. 6a) and LV (Fig. 6b), the adsorption capacity increases due to the increase in concentration gradient and the decrease of mass transfer resistance effects38,39, while percent removal decreases owing to saturation of adsorbent sites40. For RB, the adsorption capacity increases from about 2.5 to 9.6 mg/g, while the percentage removal decreases from about 96 to 62% at an initial concentration range of 10–60 ppm. On the other hand, the adsorption capacity of LV increases from about 2.2 to 12.4 mg/g, and the percent removal decreases from about 83.8 to 47.8% at an initial concentration range of 10–100 ppm.

The qevs. Ce plot for RB (Fig. 6c) is L-shaped manifesting single layer adsorption, while that of LV (Fig. 6d) is S-shaped demonstrating multi-layer adsorption. This was further confirmed when adsorption isotherms were fitted to Langmuir, Freundlich, and Sips models using linear regression (Table 4; Fig. 6, Eqs. S1−S9). For RB adsorption isotherm, Langmuir exhibited the best fitting plot due to its highest R2 and lowest χ2 indicating a monolayer adsorption. This was further validated by calculating the separation factor (RL). RL values ranged between 0 and 1, implying favorable adsorption (Table S6, SI). As for LV adsorption isotherm, Sips fit showed a higher R2 value than Langmuir and Freundlich fits, while Freundlich fit showed lower RMSE and χ2 values than Langmuir and Sips isotherms which indicates the possibility of multi-layered adsorption. To better understand the adsorption behavior, non-linear regression analysis (Table 5) was performed for the isotherms using R studio software (Table 5), and it revealed the highest R2 values and lowest RMSE values for Sips model in case of both RB and LV which implies a combined Langmuir and Freundlich adsorption behavior41). The D-R model was also used to calculate the binding energies for adsorption. Energy estimated for RB was less than 8 KJ/mol indicating physisorption42 (Figs. S9, S10 of SI).

Further studies were performed under varying adsorbent doses to investigate the effect of adsorbent amount on the percent removal and adsorption capacity of RB and LV (Fig. 7a–d). In case of RB, the adsorption capacity increased with increasing the adsorbent dose at the lower initial concentrations of 10 and 15 ppm due to increase in the number of active sites on the adsorbent, while decreased at the initial concentrations of 25 and 50 ppm, probably due to overlapping of active sites as a result of particle aggregation43. For the percent removal, it increased with increasing the adsorbent dose at the four studied initial concentrations, probably due to increased surface area of the adsorbent44. In case of LV, a similar behavior was observed where the adsorption capacity decreased while the percent removal increased with increasing the adsorbent dose at the four studied initial concentrations, possibly for the same reasons discussed for RB. Similar results have been reported in literature45,46.

Effect of adsorbent dose on percent removal and adsorption capacity of RB (a,b) and LV (c,d) onto HAP-C 700 A under different initial concentrations for 3.5 h contact time at pH 7 for RB and pH 4 for LV. Effect of temperature on: (e) RB and (f) LV percent removal at an initial concentration of 25 ppm, adsorbent dose of 3.8 g/L, contact time of 3.5 h, and at pH 7 for RB and pH 4 for LV.

Exploratory data analysis on process variables

To assess the relation between the dependent variable (removal) and the independent variables (dose, time, and initial concentration), a matrix scatter plot (Fig. S12) was constructed. For RB (Fig. S12a), it is clear from the shape of the scattering of the points that there exists a relation between the dependent and independent variables. The relation can be strongly observed in case of the independent variable X1, i.e. the dose, and the dependent variable. For the rest of the independent variables, there exists a relation, however, not as powerful as with the dose. Nevertheless, the independent variable X3, i.e., the initial concentration, seems to have a stronger relation to the removal than the X2 independent variable, which is the time. Similar observations can be deduced for LV (Fig. S12b) removal from the matrix scatter plot, where there is strong relation between the removal and the dose, and lesser relation between the initial concentration and the removal, however stronger than the relation between the time and the removal.

To assess the relation between the independent variables, interaction plots (Fig. S13a,b) were investigated. In case of RB removal (Fig. S13a), the interaction plots reveal that there is an interaction between the dose and time. There also seems to be an interaction between the dose and initial concentration. However, there is no clear relation between the time and initial concentration. For LV (Fig. S13b), it can be deduced that there is an interaction between the independent variables, i.e., between initial concentration and time, and between dose and initial concentration.

Quantile regression for process parameters

In this study, it was not possible to perform linear regression analysis since the distribution of sample mean is not normal. Given the small sample size and the lack of normal distribution in the dependent variable, quantile regression using the median as the quantile is deemed an appropriate method to capture the underlying dynamics. After conducting a non-parametric quantile regression analysis, the following model was obtained for RB, where the statistical analysis showed that all the interactions were insignificant (i.e., P > 0.05) unlike what was crudely observed in the interaction plots. Therefore, the interactions do not appear in the equation.

The model equation shows that the removal increases with increasing the dose and time, and with decreasing the initial concentration. The model has a large value of Nagelkerke Pseudo R squared which is 0.949163. This means that 94.9% of the variation in the values of the removal RB is explained by the model.

In case of LV removal, the following model was obtained.

The model shows a large value of Nagelkerke pseudo R2 which is 0.991310. This implies that 99.13% of the variation in the values of the removal of LV is explained by the model.

As was encountered with RB, the interactions were insignificant (i.e., P > 0.05). Similarly, LV removal is directly proportional to dose and time, while inversely proportional to initial concentration. These findings for LV and RB are consistent with the adsorption profile trends depicted in Fig. 6.

Thermodynamic analysis

Figure 7e and f show the effect of temperature on the percent removal of RB and LV at a fixed time, dose, and initial concentration. As temperature increases, the percent removal of both contaminants decreases implying an exothermic reaction. This is confirmed by the negative values of the enthalpy, ΔH (Table 6) as estimated from van’t Hoff plot (Fig. S11, SI). Furthermore, the values of ΔH lie between 10 and 40 KJ/mol indicating physisorption which thus corroborates the findings of the equilibrium D-R model47. Also, the negative values of Gibbs free energy, ΔG (Table 6) indicate a spontaneous reaction, while the negative entropy, ΔS (Table 6) values indicate less randomness due to adsorption.

Binary adsorption in distilled and tap water

The removal efficiencies of RB and LV in binary systems in distilled water were compared to their counterparts in single systems at an initial concentration of 10 ppm and under neutral pH conditions (Fig. 8a). No significant difference (P > 0.05) between the percent removal in single and binary systems for both RB and LV was observed, inferring non-competitive adsorption. Previous report indicated competitive adsorption in binary systems of RB and methylene blue dyes captured onto durian rind48.

Herein it is suggested that RB and LV bind to HAP-C 700 A at different adsorption sites. At pH 7, RB exists as a zwitterion with positive amine groups and negative carboxylic groups and hence can bind to the negatively charged HAP-C 700 A via the amine groups. LV at pH 7, on the other hand, has been previously reported to exist as either an electrophilic neutral molecule or a nucleophilic zwitterion49. Hence, the negatively charged HAP-C 700 A would more likely bind with the molecular form of LV, being an electrophile, than with its zwitterionic form. Binding can possibly occur via hydrogen bonding between the OH of LV with the OH groups on HAP-C 700 A, or via n-π donor-acceptor interaction between HAP-C 700 A and the aromatic ring of LV50.

In tap water (Fig. 8b), the removal efficiency of RB in single- and two-component systems is the same and is also comparable to that obtained in distilled water, However, in case of LV, the removal decreased in the binary system relative to the single system possibly due to competition from RB. The single and binary removal efficiencies of LV were slightly enhanced in tap water relative to distilled water systems. In tap water, the presence of minerals which form ionic atmospheres around LV can potentially change the charge distribution on LV and improve its binding to HAP-C 700 A. The adsorbent, thus, holds promise for applicability in real water systems. It is worth mentioning that tap water in Egypt contains chlorides in the range of 13.93–96.5 ppm, nitrates ranging from 0.41 to 6.43 ppm, aluminum from 0.018 to 0.392 ppm, and iron from 0.024 to 0.272 ppm all over the four seasons of the year. Total alkalinity ranges from 111.4 to 147.4 ppm, while total organic carbon varies between 2.34 and 5.26 ppm51. The sodium content in Egypt’s Cairo tap water averages at about 21.6 ± 1.4 ppm, while the average concentrations of potassium and magnesium are 8.5 ± 0.9 and 14.7 ± 0.7 ppm, respectively52.

Regeneration

As shown in Fig. 8c, after four cycles of adsorption/desorption of RB, HAP-C 700 A was successfully regenerated as the percent removal remained almost constant over the four cycles. However, the adsorbent was less recyclable in case of LV as the percent removal decreased by about 20% in the second cycle then remained almost constant throughout the rest of the cycles. These results are similar to previously reported work that regenerated waste-derived hydroxyapatite using 0.1 M HCl after adsorption of Congo Red dye51, sodium alginate templated hydroxyapatite/calcium silicate composite adsorbents using calcination at 350 ℃ after adsorption of Eriochrome Blue Black R dye52, magnetic hydroxyapatite using ethanol after the adsorption of phenol53, and metformin-embedded biocompatible chitosan/poly(vinyl alcohol) beads using water/ethanol mixture after the adsorption of levofloxacin54. The weaker binding of RB could be owed to its zwitterionic nature at pH 7, while LV is positively charged at pH 4. This is in line with the kinetics findings which showed that RB at pH 7 is adsorbed on HAP-C 700 A faster than LV at pH 4.

Comparison of the removal efficiencies of RB and LV in single and binary distilled water systems at pH 7 and initial concentration of 10 ppm at adsorbent dose of 3.8 g/L (a), Comparison of the removal efficiencies of RB and LV in single and binary tap water systems (b), Regeneration study of HAP-C 700 A after adsorption/desorption cycles of RB and LV at pH 7 and 4, respectively, at initial concentration of 10 ppm and adsorbent dose of 3.8 g/L using ethanol absolute as a desorbing agent (c).

Mechanism of adsorption

FTIR spectra of HAP-C 700 A before and after adsorption of RB and LV (Fig. 9) show that the OH broad peak of the adsorbent before adsorption has shifted from 3466.9 to 3446.4 and 3448.5 cm− 1 for RB and LV, respectively, after adsorption indicating the possible contribution of OH groups in adsorption. Possible interactions could be H-bonding between the OH groups of HAP-C 700 A and the OH groups of RB at pH 7, electrostatic physical interactions between the negatively charged HAP-C 700 A and amine groups of RB at pH 7, H-bonding between OH groups of HAP-C 700 A and OH groups of LV at pHs 4 and 7, n-π donor-acceptor interaction between the negatively charged HAP-700 A and the aromatic rings of the electrophilic neutral LV at pH 7, electrostatic physical interactions between the positively charged LV and slightly negative to almost neutral HAP-700 A at pH 4.

Comparison with literature

Table 7 compares the performance of the HAP-C 700 A against various hydroxyapatite-based adsorbents. The performance of HAP-C 700 A is higher or comparable to some of these adsorbents, particularly the waste-based egg shell hydroxyapatite and the composites of hydroxyapatite with chitosan or with humic acid. The maximum adsorption capacity of HAP-C 700 A is, however, lower than that of nanohydroxyapatite or the composites of hydroxyapatite with alginate, and this can be attributed to the relatively low surface area of HAP-C 700 A which is a result of probable sintering. Also, incorporating alginate in some composites could have enhanced the functionality of the composites. Nevertheless, HAP-C 700 A still holds prominent advantage in being waste-derived and this would minimize the cost of raw materials in the synthesis process.

Conclusion

As a value-added product from the industrial refuse CKD, HAP-C nanocomposite was synthesized using a novel approach. Citric acid was used effectively to chelate and separate the calcium from the CKD. The chelate complex was then converted into a mixture of calcium carbonate and carbon via heating. The XRD, FTIR, and TEM analyses confirmed the composite’s synthesis. To investigate the impact of surface area, pore volume, and pore size on the adsorption process, the textural and surface characteristics of the composite were also examined. The synthetic composite performance in adsorption was evaluated. With concentrations of 10, 15, and 25 ppm for RB and 10 and 15 ppm for LV, the adsorbent demonstrated excellent removal efficiencies of 96% and 86%, respectively. It was experimentally observed and theoretically confirmed by non-parametric quantile regression that RB and LV removal efficiencies increase with decreasing the initial concentration and with increasing the time and adsorbent dose. Linear and non-linear regression analyses showed that the adsorption isotherms of RB and LV followed Sips model which indicates combined Langmuir and Freundlich behavior. Preliminary assessment of the binary system in distilled and tap water showed that there is little to no competition between the two contaminants on the active sites, and the composite has a high potential for simultaneous removal of RB and LV. The interaction was physisorption, and the thermodynamic study showed that both RB and LV spontaneously adsorb onto HAP-C 700 A. Further evidence for this conclusion came from FTIR tests performed before and after adsorption, which indicated that OH groups are responsible for the binding, which most likely involves hydrogen bonds and electrostatic attraction forces. The kinetic study showed that both adsorbates followed the pseudo-second order model of adsorption, which implies that adsorption occurs via surface reaction, film, and pore diffusion. The proposed synthesis process is simpler than those reported in literature for other hydroxyapatite-carbon composites as it involves a reduced number of steps that do not utilize harsh chemicals owing to the use of only one precursor for both carbon and calcium. The process also utilizes, for the first time, CKD waste as a raw material and converts it into an added-value product. The unreacted CKD could be used as an alkali-free ecofriendly material in other industries such as tiles and cement. All these credentials together would make the process a promising candidate for scaling up.

Data availability

Data is available within article and supporting material.

References

Seo, M. et al. Recycling of cement kiln dust as a raw material for cement. Environments 6 (10), 113 (2019).

Nie, S. et al. Analysis of theoretical carbon dioxide emissions from cement production: methodology and application. J. Clean. Prod. 334, 130270 (2022).

Sreekrishnavilasam, A., King, S. & Santagata, M. Characterization of fresh and landfilled cement kiln dust for reuse in construction applications. Eng. Geol. 85 (1–2), 165–173 (2006).

Darweesh, H. Hazardous-Effects-of-Electrostatic-Precipitator-Cement-Kiln-Bypass-Dust-Waste-on Human-Health. Malik Badshah (eds). 1–35. (Prime Archives in Biosciences. Hyderabad, India: Vide Leaf, 2020).

Meo, S. A. Health hazards of cement dust. Saudi Med. J. 25 (9), 1153–1159 (2004).

Elbaz, A. et al. Review of beneficial uses of cement kiln dust (CKD), fly ash (FA) and their mixture. J. Mater. Environ. Sci. 10 (11), 1062–1073 (2019).

Al-Bakri, A. Y., Ahmed, H. M. & Hefni, M. A. Cement kiln dust (CKD): potential beneficial applications and eco-sustainable solutions. Sustainability 14 (12), 7022 (2022).

El Zayata, M., Elagroudyb, S. & Haggara, S. E. Equilibrium sorption isotherms for removal of heavy metals using cement kiln dust. Int. J. Therm. Environ. Eng. 15 (1), 71–79 (2017).

Huntzinger, D. N. et al. Mineral carbonation for carbon sequestration in cement kiln dust from waste piles. J. Hazard. Mater. 168 (1), 31–37 (2009).

Ibrahim, A. H., Lyu, X. & ElDeeb, A. B. Synthesized zeolite based on Egyptian boiler ash residue and kaolin for the effective removal of heavy metal ions from industrial wastewater. Nanomaterials 13 (6), 1091 (2023).

Zhao, H. et al. Tuning the dissolution kinetics of wollastonite via chelating agents for CO 2 sequestration with integrated synthesis of precipitated calcium carbonates. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 15 (36), 15185–15192 (2013).

Minh, D. P. et al. Carbonate-containing apatite (CAP) synthesis under moderate conditions starting from calcium carbonate and orthophosphoric acid. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 33 (5), 2971–2980 (2013).

Omraei, M. et al. Study of the removal of zn (II) from aqueous solution using polypyrrole nanocomposite. Desalination 271 (1–3), 248–256 (2011).

Huang, X., Gao, N. & Zhang, Q. Thermodynamics and kinetics of cadmium adsorption onto oxidized granular activated carbon. J. Environ. Sci. 19 (11), 1287–1292 (2007).

Simonin, J. P. On the comparison of pseudo-first order and pseudo-second order rate laws in the modeling of adsorption kinetics. Chem. Eng. J. 300, 254–263 (2016).

Bolster, C. H. & Hornberger, G. M. On the use of linearized Langmuir equations. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 71 (6), 1796–1806 (2007).

Hema, M. & Arivoli, S. Comparative study on the adsorption kinetics and thermodynamics of dyes onto acid activated low cost carbon. Int. J. Phys. Sci. 2 (1), 10–17 (2007).

Tzabar, N., Ter, H. & Brake Adsorption isotherms and sips models of nitrogen, methane, ethane, and propane on commercial activated carbons and polyvinylidene chloride. Adsorption 22, 901–914 (2016).

Chen, X. Modeling of experimental adsorption isotherm data. Information 6 (1), 14–22 (2015).

MacQueen, J. Some observations concerning the van’t Hoff equation. J. Chem. Educ. 44 (12), 755 (1967).

Kirimura, K. & Yoshioka, I. Citric acid, in Comprehensive Biotechnology. 158–165. (Elsevier, 2019).

Li, J. et al. Preparation and properties of calcium citrate nanosheets for bone graft substitute. Bioengineered 7 (5), 376–381 (2016).

Singh, G. et al. Impact of post-heat-treatment on the surface-roughness, residual stresses, and micromorphology characteristics of plasma-sprayed pure hydroxyapatite and 7%-Aloxite reinforced hydroxyapatite coatings deposited on titanium alloy-based biomedical implants. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 18, 1358–1380 (2022).

Zhou, Q. Q., Chen, X. Y. & Wang, B. An activation-free protocol for preparing porous carbon from calcium citrate and the capacitive performance. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 158, 155–161 (2012).

Ivanets, A. et al. Adsorption performance of hydroxyapatite with different crystalline and porous structure towards metal ions in multicomponent solution. J. Water Process. Eng. 32, 100963 (2019).

Rout, S. et al. Removal of uranium (VI) from water using hydroxyapatite coated activated carbon powder nanocomposite. J. Environ. Sci. Health Part. A 55 (5), 596–605 (2020).

Jayaweera, H. et al. Synthesis of multifunctional activated carbon nanocomposite comprising biocompatible flake nano hydroxyapatite and natural turmeric extract for the removal of bacteria and lead ions from aqueous solution. Chem. Cent. J. 12 (1), 1–14 (2018).

Shavandi, A. et al. Synthesis of nano-hydroxyapatite (nHA) from waste mussel shells using a rapid microwave method. Mater. Chem. Phys. 149, 607–616 (2015).

Mujahid, M., Sarfraz, S. & Amin, S. On the formation of hydroxyapatite nano crystals prepared using cationic surfactant. Mater. Res. 18, 468–472 (2015).

Santos, M. H. et al. Synthesis control and characterization of hydroxyapatite prepared by wet precipitation process. Mater. Res. 7, 625–630 (2004).

Mostafa, A. A., Oudadesse, H. & El-Sayed, M. M. A quantitative approach for studying the bioactivity of nanohydroxyapatite/gold composites. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part. A 103 (11), 3483–3492 (2015).

Sadat-Shojai, M. et al. Synthesis methods for nanosized hydroxyapatite with diverse structures. Acta Biomater. 9 (8), 7591–7621 (2013).

Oladipo, A. A. & Gazi, M. Uptake of Ni2 + and rhodamine B by nano-hydroxyapatite/alginate composite beads: batch and continuous-flow systems. Toxicol. Environ. Chem. 98 (2), 189–203 (2016).

Inyinbor, A. A., Adekola, F. A. & Olatunji, G. A. Adsorption of rhodamine B dye from aqueous solution on Irvingia gabonensis biomass: kinetics and thermodynamics studies. S. Afr. J. Chem. 68, 115–125 (2015).

Mohammadi, M. et al. Removal of rhodamine B from aqueous solution using palm shell-based activated carbon: adsorption and kinetic studies. J. Chem. Eng. Data 55 (12), 5777–5785 (2010).

Bayomie, O. S. et al. Novel approach for effective removal of methylene blue dye from water using fava bean peel waste. Sci. Rep. 10 (1), 7824 (2020).

Farghal, H. H., Nebsen, M. & El-Sayed, M. M. Eco-friendly biopolymer/activated charcoal magnetic nanocomposites with enhanced stability and adsorption properties for water treatment applications. J. Polym. Environ. 31 (12), 5338–5354 (2023).

Mohammad, S. G. & El-Sayed, M. M. Removal of imidacloprid pesticide using nanoporous activated carbons produced via pyrolysis of peach stone agricultural wastes. Chem. Eng. Commun. 208 (8), 1069–1080 (2021).

Farghal, H. H., Nebsen, M. & El-Sayed, M. M. H. Multifunctional Chitosan/Xylan-Coated magnetite nanoparticles for the simultaneous adsorption of the emerging contaminants pb(II), salicylic acid, and congo red dye. Water 15 (4), 829 (2023).

Acemioğlu, B. Removal of a reactive dye using NaOH-activated biochar prepared from peanut shell by pyrolysis process. Int. J. Coal Prep. Util. 42 (3), 671–693 (2022).

Sips, R. On the structure of a catalyst surface. J. Chem. Phys. 16 (5), 490–495 (1948).

Zahakifar, F., Keshtkar, A. R. & Talebi, M. Synthesis of sodium alginate (SA)/polyvinyl alcohol (PVA)/polyethylene oxide (PEO)/ZSM-5 zeolite hybrid nanostructure adsorbent by casting method for uranium (VI) adsorption from aqueous solutions. Prog. Nucl. Energy 134, 103642 (2021).

Noreen, S. et al. ZnO, MgO and FeO adsorption efficiencies for direct sky blue dye: equilibrium, kinetics and thermodynamics studies. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 9 (3), 5881–5893 (2020).

Muniyandi, M. & Govindaraj, P. Potential removal of methylene blue dye from synthetic textile effluent using activated carbon derived from palmyra (palm) shell. Materi. Today Proc. 47 299–311. (2021).

Lotfi, R. et al. Synthesis and characterization of PAMAM/SiO2 nanohybrid as a new promising adsorbent for pharmaceuticals. Microchem. J. 146, 1150–1159 (2019).

Husein, D. Z., Hassanien, R. & Al-Hakkani, M. F. Green-synthesized copper nano-adsorbent for the removal of pharmaceutical pollutants from real wastewater samples. Heliyon 5 (8), e02339 (2019).

Egbosiuba, T. C. et al. Ultrasonic enhanced adsorption of methylene blue onto the optimized surface area of activated carbon: Adsorption isotherm, kinetics and thermodynamics. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 153, 315–336 (2020).

Asbollah, M. A. et al. Dynamics and thermodynamics for competitive adsorptive removal of methylene blue and rhodamine B from binary aqueous solution onto durian rind. Environ. Monit. Assess. 194 (9), 645 (2022).

Yan, B. & Niu, C. H. Modeling and site energy distribution analysis of levofloxacin sorption by biosorbents. Chem. Eng. J. 307, 631–642 (2017).

Nazar, M. F. et al. pH-dependent probing of levofloxacin assimilated in surfactant mediated assemblies: insights from photoluminescent and chromatographic measurements. J. Mol. Liq. 220, 26–32 (2016).

Bensalah, H. et al. Azo dye adsorption on an industrial waste-transformed hydroxyapatite adsorbent: kinetics, isotherms, mechanism and regeneration studies. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 8 (3), 103807 (2020).

You, Y. et al. Sodium alginate templated hydroxyapatite/calcium silicate composite adsorbents for efficient dye removal from polluted water. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 141, 1035–1043 (2019).

Wang, X. Preparation of magnetic hydroxyapatite and their use as recyclable adsorbent for phenol in wastewater. Clean Soil Air Water 39 (1), 13–20 (2011).

Ramsheh, N. A. et al. Metformin-embedded biocompatible Chitosan/Poly (vinyl alcohol) beads with superior adsorption properties toward lead (II) and levofloxacin. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 5 (4), 3148–3160 (2023).

Yusuff, O., Bello, M. & Odeyale, D. Adsorption of rhodamine B by egg shell hydroxyapatite. Ilorin J. Sci. 11 (3), 414–420 (2024).

Wang, G. et al. Surface-bound humic acid increased rhodamine B adsorption on nanosized hydroxyapatite. J. Dispers. Sci. Technol. 38 (5), 632–641 (2017).

Jamarun, N. et al. Effect of chitosan concentration on hydroxyapatite/chitosan composite synthesis using the in-situ method as a dye adsorbent. Kuwait J. Sci. 51 (4), 100252 (2024).

Ciobanu, G. & Harja, M. Studies on the sorption of levofloxacin from aqueous solutions onto nanohydroxyapatite. Rev. Roum. Chim. 63 (63), 593–601 (2018).

Jebri, S. et al. Eco-friendly design of alginate-coated hydroxyapatites for the effective removal of rhodamine B dye from water: equilibrium, kinetics and thermodynamic study. Desalin. Water Treat. 282, 276–289 (2023).

Acknowledgements

We would like to extend our sincere gratitude to Dr. Salah El-Haggar at the Mechanical Engineering Department, The American University in Cairo, for kindly providing us with the cement kiln dust.

Funding

This work was supported by the American University in Cairo and the USAID (ASHA grant, number: AID-ASHA-G-17-00010) for providing the required funds and facilities.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A. S. A.: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Data analysis, Writing – original draft, editing and visualization. H.H.F.: Review data analysis, writing – original draft, Visualization & editing. N.Y.: Statistical analysis, software, reviewing. M.M.H.E.: Conceptualization, reviewing, supervision, and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ahmed, A.S., Farghal, H.H., Youssef, N. et al. A modified approach towards facile and green conversion of cement kiln dust wastes to efficient hydroxyapatite-carbon nanocomposite water adsorbents. Sci Rep 15, 6284 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87249-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87249-4