Abstract

It has been documented that D-dimer levels have potential utility as a measure of tumor activity in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), however whether it can be used as a predictive marker of treatment outcome has not been established. This study means to retrospectively evaluate the role of D-dimer in prediction of treatment efficacy in patients with DLBCL. 151 patients with newly diagnosed DLBCL were enrolled. Blood samples were taken from those patients during the initial visit to our hospital and again after two cycles of chemotherapy to measure D-dimer levels. The link between plasma D-dimer concentrations and patients’ clinical characteristics was explored before and after treatment. D-dimer levels within the range of 0–1 µg/mL were considered negative, while readings above this range were considered positive. D-dimer difference percentage (Ddp) represents the percentage change in D-dimer levels before and after chemotherapy, calculated as (post-chemotherapy D-dimer minus pre-chemotherapy D-dimer) / pre-chemotherapy D-dimer × 100. Patients showed statistically different plasma D-dimer levels at initial consultation across treatment-response groups: CR (0.63 µg/mL [0.43–1.27]), PR (1.39 µg/mL [0.73–2.46]), SD (0.89 µg/mL [0.59–1.24]), and PD (1.34 µg/mL [0.67–2.62]). After chemotherapy, the PR group exhibited a mean D-dimer level of -0.38 µg/mL (range − 1.64 to -0.11), which was significantly lower than that of the PD group (mean 0.04 µg/mL, range − 0.40 to 0.79; p < 0.05). The CR group revealed significantly lower initial D-dimer levels (median 0.63 µg/mL) and greater reductions after chemotherapy compared to the non-CR group (median 1.17 µg/mL, p < 0.05). Patients with coagulation disorders such as DIC, DVT, or PE were excluded to minimize confounding factors. While this study demonstrates the utility of D-dimer in predicting short-term treatment response, the relationship with long-term outcomes such as PFS and OS requires further investigation. Patients who respond well to chemotherapy typically exhibit lower D-dimer levels at the initial diagnosis. Those in the SD or PD groups usually experience a greater increase in D-dimer levels following chemotherapy. Consequently, variations in plasma D-dimer levels before and after treatment may offer valuable insights for evaluating the efficacy of chemotherapy treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is one of the most prevalent and aggressive types of lymphoma. The primary treatment approach has traditionally relied on the R-CHOP regimen, which achieves a relatively high complete remission rate of approximately 70–90%1. However, even with these promising numbers, the 5-year progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) rates still hover around 60–70%2, leaving a significant subset of patients, roughly 30–40%, unresponsive to standard therapies over the long term3. This glaring treatment gap highlights the urgent need for innovative strategies to improve DLBCL treatment outcomes.

DLBCL presents a challenging landscape characterized by considerable heterogeneity among patients in terms of tumor burden, disease progression, chemosensitivity, and prognosis. Conventional tools for assessing treatment efficacy, such as PET-CT and CT imaging, are widely used but have inherent limitations4. They are relatively expensive, involve the radioactive harm for dynamic monitoring, and frequently result in patient non-compliance with regular assessments. This non-compliance leads to delays in obtaining crucial efficacy evaluation results. In response to these challenges, there is a compelling need to simplify the evaluation of DLBCL treatment efficacy, aiming for accessibility and simplicity comparable to routine blood tests. This approach not only holds the potential to reduce the time intervals between chemotherapy cycles but also facilitates prompt adjustments to treatment regimens based on individual patient responses to chemotherapy.

Furthermore, the well-established link between coagulation dysfunction and tumor progression adds an intriguing dimension to this study. The coagulation and fibrinolytic systems play pivotal roles in tumor invasion and metastasis5. Within this intricate web of interactions, D-dimer, a product of fibrinolysis induced by fibrinolytic enzymes, emerges as a particularly promising candidate. It has garnered significant attention in recent years owing to its potential as a sensitive and real-time molecular marker, rapidly eliminated from the body6. While prior research has established associations between elevated D-dimer levels and solid tumors like breast7, lung8, gastric9, and colorectal malignancies10,11, the specific role of D-dimer in malignant lymphoma has remained a relatively uncharted territory. Moreover, while numerous studies have explored its links to patient prognosis12,13, there remains a notable scarcity of research focused on its utility as a marker for evaluating treatment outcomes following standard chemotherapy cycles.

This study addresses these significant gaps by embarking on a comprehensive investigation of D-dimer levels in 151 patients with newly-diagnosed DLBCL. This study meticulously examines the fluctuations in D-dimer levels before and after therapy, offering a retrospective analysis of D-dimer’s potential in assessing the effectiveness of DLBCL treatment. By doing so, this research aims to illuminate novel avenues for enhancing treatment outcomes and fostering individualized, responsive therapies within the realm of DLBCL.

Patients and methods

Clinical data

This study involved the inclusion of 151 patients diagnosed with Diffuse Large B-cell Lymphoma (DLBCL) over specific timeframes. The patient cohort was collected from three medical institutions: the Second Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University (November 2020 to January 2023), the First Affiliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University (January 2018 to February 2023), and the Second Affiliated Hospital of Dalian Medical University (January 2018 to January 2023). To depict the inclusion process visually, refer to Fig. 1.

The inclusion criteria were rigorous and included the following: (i) complete clinical data: all patients were required to have comprehensive clinical records, (ii) pathological confirmation: patients had to have a confirmed diagnosis of DLBCL through pathological examinations, (iii) measurable lesions: patients were included if they had measurable lesions, and (iv) all treatment-naïve: the study focused exclusively on newly diagnosed patients who had not previously received radiotherapy or chemotherapy. To minimize confounding factors, patients with concurrent medical conditions such as coronary artery disease, trauma, pregnancy, or inflammation, which could elevate D-dimer levels, were excluded. Additionally, patients with known disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), deep vein thrombosis (DVT), or pulmonary embolism (PE) were excluded from the study. Routine imaging and coagulation tests (prothrombin time, activated partial thromboplastin time, fibrinogen, and fibrin degradation products) were conducted at baseline to rule out these complications.

Treatment strategies

All 151 DLBCL patients received treatment following either the standard R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone) regimen. 30% of patients received anticoagulant treatment. The median number of chemotherapy cycles was 6 (range 2–8). The R-CHOP protocol involved the administration of rituximab at a dose of 375 mg/m² on day 1 of each cycle, cyclophosphamide at 750 mg/m², doxorubicin at 50 mg/m², and vincristine at 1.4 mg/m² (capped at a maximum dose of 2 mg) on day 1, along with prednisone at 100 mg on days 1–5 of a 21-day cycle.

Research methods

At the initial appointment and again two weeks after completing two cycles of treatment, fasting venous blood samples were collected from all patients. Plasma D-dimer levels were quantified using the immunoturbidimetric approach with the CP3000 coagulation system from SEKISUI MEDICAL CO., LTD., Tokyo, Japan. D-dimer levels within the range of 0–1 µg/mL were considered negative, while readings above this range were considered positive.

Efficacy evaluation

National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines for the evaluation of lymphoma outcomes recommend a PET-CT or CT at the time of initial diagnosis and again after cycles of chemotherapy to determine whether the disease has been eradicated or not. Complete response (CR) is defined as disappearance of all lesions. Partial response (PR) is defined as a reduction in lesions of more than 50% from the initial count. Stable disease (SD) is defined as a decrease in the total length of the lesions at diagnosis but no PR or an increase but no disease advancement. Progressive disease (PD) is defined as an increase of > 50% in the number of lesions present at diagnosis or the development of additional lesions. We classify patients as either “CR group”, “PR group”, “SD group”, or “PD group” based on their outcomes. After two cycles of chemotherapy, the relationship between changes in D-dimer levels and treatment outcome was evaluated.

Statistical methods

The data collected were subjected to rigorous statistical analysis using R4.2.2 statistical software. Since most quantitative data did not adhere to a normal distribution and chi-squared tests, the measurements were reported as medians and quartiles. The Kruskal-Wallis test was utilized to compare different groups, and the significance level was Bonferroni adjusted when comparing two groups. The analysis also involved Spearman’s correlation analysis to explore relationships between variables. Differences were considered statistically significant when the p-value was < 0.05.

Ethical approval

This retrospective study was conducted in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki and received approval from the Ethics Committee of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University (approval number: 2023KY-13-01).

Results

Clinical characteristics of the patients

The study cohort included 67 male patients (44.4%) and 84 female patients (55.6%), with a median age of 63 years (range 21–90 years). Ann Arbor stage I–II accounted for 32.5% of the patients (49 cases), while stage III–IV was observed in 67.5% of the patients (102 cases). B symptoms were present in 30.5% of the patients (46 cases), and 53.0% of the patients (80 cases) had an IPI score > 2.

D-dimer levels associated with Ann Arbor stage, LDH, and IPI score in DLBCL patients

Table 1 indicated the correlation between D-dimer levels at the time of diagnosis and several clinical features. D-dimer levels at the time of initial consultation were significantly correlated with Ann Arbor stage, the existence of B symptoms, and IPI score (p-Values = 0.0001895, 0.0008701, and 0.0001328, respectively), but not with age, gender, or LDH (p-Values = 0.3429, 0.6410, and 0.3883, respectively).

The D-dimer level and its change before and after chemotherapy in different response groups

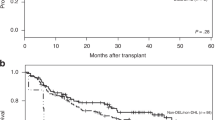

To compare D-dimer variations in different response groups, three markers are used. The first signal is the D-dimer level at initial diagnosis (Di), the second is the change in D-dimer levels before and after chemotherapy, i.e., post-chemotherapy D-dimer minus pre-chemotherapy D-dimer (referred to below as Dd, D-dimer difference), and the third is the difference percentage (referred to below as Ddp, i.e. Dd/ Di * 100%). Table 2; Fig. 2 illustrate the results.

Analysis of the differences in the distribution of results in the different response groups found that:

At initial consultation, the mean D-dimer levels were significantly different across the response groups: CR group was 0.63 µg/mL (range 0.43–1.27), PR group was 1.39 µg/mL (range 0.73–2.46), SD group was 0.89 µg/mL (range 0.59–1.24), and PD group was 1.34 µg/mL (range 0.67–2.62) (p < 0.05). After chemotherapy, the mean D-dimer levels were − 0.38 µg/mL (range − 1.64 to -0.11) for the PR group and 0.04 µg/mL (range − 0.40 to 0.79) for the PD group. The difference between the two groups was statistically significant (p < 0.05).

The Di from the four groups has statistically significant difference, and the results of the two-by-two comparison showed that Di in CR group was lower than that in PR and PD groups (p < 0.05), while the rest of the groups have no statistically significant difference when compared.

The variations in Dd from the four groups were statistically significant, and the two-by-two comparison revealed that the Dd was lower in PR group than any other group (p < 0.05), although the differences between the remaining groups were not statistically significant for comparison.

There was a statistically significant difference in Ddp between the four groups, and the results of the two-way comparison showed that Ddp was lower in PR group than in any other group (p < 0.05), while the remaining groups have no substantial difference when compared.

The significant reduction in D-dimer levels observed in the CR and PR groups post-chemotherapy highlights the utility of this biomarker in monitoring tumor burden and treatment efficacy. In contrast, minimal reductions or even increases in D-dimer levels in the SD and PD groups may reflect persistent disease activity or progression. These findings suggest that D-dimer levels, as a dynamic and readily measurable marker, could complement imaging-based assessments, particularly in settings where frequent imaging is impractical or unavailable.

Changes in the distribution of the remaining indicators among groups

Table 3 revealed that FDP and ATIII were distributed differently across groups at the time of diagnosis, with FDP being lower in CR group than in PR group and ATIII being higher in CR group than in PR group, while differences in the remaining groups were not statistically significant.

To evaluate the role of D-dimer levels in achieving complete remission (CR), the study population was divided into CR and non-CR groups (PR, SD, and PD combined as non-CR). Table 4 showed the result. At initial consultation, the CR group had a significantly lower median D-dimer level of 0.63 µg/mL (range 0.43–1.27) compared to the non-CR group with a median D-dimer level of 1.17 µg/mL (range 0.59–2.62, p < 0.05). After chemotherapy, the CR group exhibited a larger reduction in D-dimer levels compared to the non-CR group (median difference: CR -0.09 µg/mL, non-CR 0.04 µg/mL, p < 0.05). These findings highlight the potential role of D-dimer in predicting complete remission.

Relevance analysis

Di was positively correlated with IPI scores, Dd was negatively correlated with IPI, and Ddp was not found to be correlated with IPI scores. See Table 5 for correlations with other indicators.

Exploratory analysis of D-dimer levels and long-term outcomes

While this study primarily focuses on D-dimer levels and their association with short-term treatment response (CR, PR, SD, PD), an exploratory analysis was conducted to assess their potential relationship with overall response rate (ORR), progression-free survival (PFS), and overall survival (OS). Due to the retrospective nature and relatively short follow-up period, comprehensive PFS and OS data were unavailable for the majority of patients. However, patients achieving CR were observed to have trends toward longer survival compared to non-CR groups, consistent with prior research linking lower D-dimer levels with improved outcomes. These findings underscore the need for prospective studies with extended follow-up to establish the prognostic utility of D-dimer in predicting long-term outcomes.

Discussion

This research discovered a link between initial D-dimer levels and how patients responded to DLBCL treatment. It showed that the success of chemotherapy related to changes in D-dimer levels before and after treatment. Specifically, after treatment, D-dimer levels dropped (negative) in patients who responded well to treatment (PR, CR, and SD groups) but increased (positive) in those whose condition worsened (PD group). The data indicated higher increases in D-dimer levels after chemotherapy in patients with a quiescent (SD) or worsening (PD) condition compared to those who had a complete (CR) or partial (PR) response. As a result, it was concluded that patients with DLBCL who experienced a significant decrease in D-dimer levels after chemotherapy might benefit more from the treatment.

Previous research has demonstrated that D-dimer is a highly effective marker for evaluating tumor activity and can be used as a screening marker for signs of tumor activity that are rapidly eliminated from the body6,14, increasing the sensitivity of this indicator and offering a new perspective beyond the TNM classification. High tumor burden is also linked to elevated D-dimer levels15. The correlation between D-dimer levels and inflammatory markers, such as neutrophil lymphocyte ratio (NLR)16, adjusted Glasgow prognostic score (mGPS)17, C-reactive protein albumin ratio (CAR)18, and albumin globulin ratio19, have also been shown to reflect tumor burden and activity, supporting these findings. More significantly, D-dimer levels are easier to be tested and monitored on a regular basis.

The putative explanations for these discoveries are discussed below in terms of the effect of tumor activity on the coagulation process and the effect of coagulation activity on tumor invasion and metastasis.

The interaction between tumor cells and endothelial cells initially results in alterations of coagulation and fibrinolysis. The release and activation of various tumor-associated coagulation factors, such as tissue factor, fibrin, and fibrinolytic enzymes20, can potentiate the coagulation system and trigger a cascade of coagulation reactions through different signaling pathways21. Several types of tumors, including lung8, prostate22, cervical23, breast7, and colorectal malignancies11, exhibit elevated levels of D-dimers, excluding those with clinical thrombosis. The dysregulation of the coagulation system may serve as an early indication of tumor cell proliferation and a significant marker of occult tumors or residual tumor cells that persist in the body after chemotherapy and remain dormant for years24. Blackwell et al. hypothesis that increased fibrinolytic activity is responsible for the elevated D-dimer levels in tumor patients25. Furthermore, according to Heit et al., tumor cells directly activate platelets and fibrinolytic proteins, disrupt the integrity of endothelial arterial walls, and stimulate the coagulation system26. Thus, elevated levels of D-dimer can aid in assessing the coagulation process and tracking tumor activity, metastasis, or recurrence.

Conversely, the activation of the coagulation system influences the biological behavior of tumors by facilitating tumor cell proliferation and invasion. The cross-linked fibrin formed during coagulation provides a foundation for tumor growth and serves as a framework for metastasis27. To establish a new blood supply at distant sites, metastatic tumor cells must detach from the primary tumor site and navigate through the lymphatic or vascular system. During this process, continuous fibrin remodeling plays a crucial role in neovascularization. Patients with tumors may exhibit symptoms of venous thromboembolism (VTE) years before any clinical manifestations. Pro-coagulant proteins and tumor cells mutually reinforce each other in a vicious cycle, intensifying the positive feedback loop that promotes neovascularization and facilitates tumor metastatic invasion. Additionally, activated fibrinogen can act as a shield for tumor cells against natural killer cells, impeding their removal and potentially worsening the prognosis. Notably, antithrombotic drugs like warfarin and low-molecular-weight heparin have been found effective in preventing and treating bloodstream metastases and prolonging overall survival in patients with tumors28. Some studies have suggested that tumor patients who experience VTE have a worse prognosis. However, Ay et al. presented opposing evidence, asserting that elevated D-dimer levels and VTE were independently associated with poor prognosis in patients with solid tumors. Consequently, the patient’s response to chemotherapy may be indicated by D-dimer levels, which reflect the level of tumor burden and cancer activity.

An established method for assessing prognosis of DLBCL is the IPI score. To enhance prognostic accuracy, a revised IPI score (R-IPI) and an expanded National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN)-IPI have been developed since the introduction of rituximab29. This development has significantly improved the outcomes of DLBCL patients. While both scoring systems offer valuable prognostic guidance, neither can effectively identify individuals at extremely high risk. Numerous studies have investigated the prognosis of DLBCL patients and proposed risk models for a more precise prediction of patient outcomes30,31. These models consider factors such as morphology (PET/CT or CT), cell origin classification, MYC rearrangement, and serological findings. However, these novel indicators, though debated in prognostic evaluation, share a common limitation-they do not capture the dynamic, real-time course of the disease and overlook substantial variations in individual responses to treatment. Moreover, morphological examinations like PET/CT or CT are costly and involve potential radioactive damage.

For the most part, individual differences in response to chemotherapy have been overlooked by previous predictive models since they were based on basic information about patients before treatment. Potentially the most crucial factor in determining a patient’s prognosis over the long run is individual variation. A patient’s prognosis is an ongoing and ever-changing procedure. Status after standard treatment can give good categorization of patients with varied prognoses, as remission rates in lymphoma have been demonstrated to be highly associated with patient indicators related to disease progression. However, the long-term prognosis of patients who obtain CR with a single standard treatment may be vastly different from those who have SD/PD after conventional therapy but achieve CR after alternate regimens or after several courses of chemotherapy. Patients’ response rates to treatment are therefore an important prognostic indicator that cannot be overlooked.

A statistically significant correlation was found between D-dimer levels at the time of diagnosis and the established prognostic score system for IPI. The findings of Ay et al. and Li et al. both highlight the significance of elevated D-dimer levels for prognosis of patients and the correlation with OS or risk of death32,33, lending credence to the conclusions drawn by Liu et al. that higher pre-treatment plasma D-dimer levels is negatively associated with OS and is an independent prognostic factor for poorer OS in patients with untreated DLBCL34. However, other researchers have found that preprimary plasma D-dimer levels were not an independent poor prognostic factor for untreated patients, although they still correlated negatively with OS, and that they were instead correlated with clinical characteristics (such as Ann-Arbor staging, LDH levels, etc.).

Research by Masatsune Shibutani et al. indicated that patients with higher D-dimer levels tended to have shorter PFS on first-line therapy for stage IV colorectal cancer31. Patients with lower D-dimer levels may have inactive tumors and smaller tumor volumes. Elevated plasma D-dimer levels predict an increased risk of tumor recurrence and a poorer prognosis, according to data from a retrospective cohort analysis of patients with epithelial carcinoma of the upper urinary tract by Chen et al. D-dimer levels have been shown to be useful in assessing the treatment and prognosis of a wide variety of malignancies35, including colorectal and uroepithelial malignancies11,35, as well as gastric9,19,36, lung8, breast7,25, cervical cancers23, and high-grade musculoskeletal sarcoma37.

Box plots of Di, Dd, and Ddp in four groups. (A) D-dimer level (Di) at initial consultation; (B) D-dimer difference (Dd), i.e., post-chemotherapy minus pre-chemotherapy; (C) Percentage change in D-dimer level before and after chemotherapy. Ddp, D-dimer level difference percentage, Dd/Di *100%. CR: complete response, PR: partial response, SD: stable disease, PD: progressive disease.

This study demonstrates the potential of D-dimer levels in improving the management of DLBCL patients and its broader implications in oncology. The correlation between baseline D-dimer levels and treatment response highlights the practicality of this readily available biomarker. Customizing treatment plans based on initial D-dimer levels could lead to more personalized and effective interventions for DLBCL patients. Additionally, our findings regarding the link between D-dimer level variations before and after chemotherapy and treatment effectiveness suggest the feasibility of real-time patient response monitoring, allowing for dynamic treatment adjustments and enhanced disease management.

The consideration of patients’ medical histories adds a layer of complexity to our analysis, as the interaction between prior conditions and DLBCL treatment responses is not always straightforward. By meticulously accounting for these historical factors, we aim to contribute a more comprehensive understanding of how patients’ health backgrounds can shape the trajectory of D-dimer levels and, consequently, treatment outcomes.

Furthermore, our research sheds light on the impact of different chemotherapy protocols within the broader R-CHOP framework. By zeroing in on patients who have undergone similar R-CHOP-based treatments, we aim to dissect the specific contributions of individual chemotherapy agents to D-dimer fluctuations. This approach provides a granular perspective that is essential for tailoring treatment strategies and optimizing therapeutic interventions for DLBCL patients.

Our study delves into overlooked post-chemotherapy changes in D-dimer levels, aiming to uncover vital insights for refining treatment strategies in DLBCL management. While acknowledging past research, our work sheds light on the significance of post-treatment D-dimer dynamics, albeit the complexities that remain. Recognizing our study’s limitations, such as its retrospective nature and small sample size, we emphasize the need for further investigations with larger cohorts and extended follow-ups to enhance our understanding of D-dimer’s role in DLBCL and other cancers.

While our study indicates a potential relationship between D-dimer levels and treatment efficacy, its role in long-term prognostic prediction requires further validation. D-dimer levels represent a unique biomarker that reflects both static tumor burden at diagnosis and dynamic changes during treatment. Unlike imaging-based assessments or static prognostic tools such as the IPI, D-dimer provides real-time insights into treatment efficacy, offering a non-invasive and cost-effective approach for monitoring disease progression. However, it remains unclear whether D-dimer levels can predict long-term outcomes such as progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS). Future studies should incorporate extended follow-up periods and larger patient cohorts to validate these findings and explore the integration of D-dimer with existing prognostic models.

Conclusion

This study underscores the potential significance of D-dimer levels in providing insights into treatment responses and prognosis in DLBCL patients. While promising, its value as a prognostic biomarker is not definitive and requires further validation in larger studies. Furthermore, D-dimer’s value extends beyond DLBCL and offers a broader perspective in the field of oncology. Despite existing challenges and limitations, further research in this area holds promise for personalized cancer care and more effective therapeutic interventions.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to privacy and confidentiality concerns but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- DLBCL:

-

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma

- R-CHOP:

-

Rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin hydrochloride (hydroxydaunomycin), vincristine sulfate (oncovin) and prednisone

- CR:

-

Complete response

- PFS:

-

Progression-free survival

- OS:

-

Overall survival

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- PET-CT:

-

Positron emission tomography-computed tomography

- NCCN:

-

National Comprehensive Cancer Network

- PR:

-

Partial response

- SD:

-

Stable disease

- PD:

-

Progressive disease

- LDH:

-

Lactate dehydrogenase

- B symptom:

-

A set of symptoms, namely fever, night sweats, and unintentional weight loss

- IPI:

-

International Prognostic Index

- Di:

-

D-dimer level at initial consultation

- Dd:

-

D-dimer level difference, post-chemotherapy minus pre-chemotherapy

- Ddp:

-

D-dimer level difference percentage, Dd/Di *100%

- PT:

-

Prothrombin time

- INR:

-

International normalized ratio

- APTT:

-

Activated partial thromboplastin time

- Fg:

-

Fibrinogen

- TT:

-

Thrombin time

- FDP:

-

Fibrin or fibrinogen degradation products

- ATIII:

-

Antithrombin-III

- VTE:

-

Venous thromboembolism

- R-IPI:

-

Revised International Prognostic Index

References

Coiffier, B. et al. CHOP chemotherapy plus rituximab compared with CHOP alone in elderly patients with diffuse large-B-cell lymphoma. N Engl. J. Med. 346, 235–242. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa011795 (2002).

Crump, M. et al. Outcomes in refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: results from the international SCHOLAR-1 study. Blood 130, 1800–1808. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2017-03-769620 (2017).

Bento, L. et al. Screening for prognostic microRNAs Associated with Treatment failure in diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Cancers (Basel). 14 https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14041065 (2022).

Younes, A. et al. International Working Group consensus response evaluation criteria in lymphoma (RECIL 2017). Ann. Oncol. 28, 1436–1447. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdx097 (2017).

Tasić, N., Paixão, T. R. L. C. & Gonçalves, L. M. Biosensing of D-dimer, making the transition from the central hospital laboratory to bedside determination. Talanta 207, 120270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.talanta.2019.120270 (2020).

Olson, J. D. D-dimer: an overview of Hemostasis and fibrinolysis, assays, and Clini cal applications. Adv. Clin. Chem. 69, 1–46, https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.acc.2014.12.001

Sringeri, S. H., Chandra, P. S. & R. R. & Role of plasma D-Dimer levels in breast Cancer patients and its correlation with clinical and histopathological stage. Indian J. Surg. Oncol. 9, 307–311. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13193-017-0682-x (2018).

Ma, M. et al. The D-dimer level predicts the prognosis in patients with lung cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 16, 243. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13019-021-01618-4 (2021).

Diao, D. et al. D-dimer is an essential accompaniment of circulating tumor cells in gastric cancer. BMC Cancer. 17 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-016-3043-1 (2017).

Li, W. et al. Prognostic role of pretreatment plasma D-Dimer in patients with solid tumors: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 45, 1663–1676, https://doi.org/10.1159/000487734

Liu, C., Ning, Y., Chen, X. & Zhu, Q. D-Dimer level was associated with prognosis in metastatic colorectal cancer: a Chinese patients based cohort study. Med. (Baltim). 99, e19243. https://doi.org/10.1097/md.0000000000019243 (2020).

Bi, X. W. et al. High pretreatment D-Dimer levels correlate with adverse clinical features and predict poor survival in patients with natural Killer/T-Cell lymphoma. PLoS One. 11, e0152842. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0152842 (2016).

Geng, Y. et al. Prognostic value of D-Dimer in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: a retrospective study. Curr. Med. Sci. 39, 222–227. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11596-019-2023-5 (2019).

Nagy, Z. et al. D-Dimer as a potential prognostic marker. Pathol. Oncol. Res. 18, 669–674. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12253-011-9493-5 (2012).

Dai, H. et al. D-dimer as a potential clinical marker for predicting metastasis and progression in cancer. Biomed. Rep. 9, 453–457. https://doi.org/10.3892/br.2018.1151 (2018).

Chen, L. et al. Diagnostic value of serum D-dimer, CA125, and neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in differentiating ovarian cancer and endometriosis. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 147, 212–218. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijgo.12949 (2019).

Yukihiro, K. et al. Impact of modified Glasgow prognostic score on predicting prognosis and modification of risk model for patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma treated with first line tyrosine kinase inhibitor. Urol. Oncol. 40, 455. .e411-455.e418 (2022).

Liao, C. K. et al. Prognostic value of the C-reactive protein to albumin ratio in colorec tal cancer: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. World J. Surg. Oncol. 19, 139, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12957-021-02253-y

Zhang, L. et al. Prognostic Value of Albumin to D-Dimer Ratio in Advanced Gastric Cancer. J Oncol 9973743, (2021). https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/9973743 (2021).

Falanga, A., Marchetti, M. & Vignoli, A. Coagulation and cancer: biological and clinical aspects. J. Thromb. Haemost 11, 223–233, https://doi.org/10.1111/jth.12075

Fernandes, C. J. et al. Cancer-associated thrombosis: the when, how and why. Eur. Respir Rev. 28 https://doi.org/10.1183/16000617.0119-2018 (2019).

Kalkan, S. & Caliskan, S. High D-dimer levels are associated with prostate cancer. Rev. Assoc. Med. Bras. 66, 649–653. https://doi.org/10.1590/1806-9282.66.5.649 (1992). ).

Li, B., Shou, Y. & Zhu, H. Predictive value of hemoglobin, platelets, and D-dimer for the surviva l of patients with stage IA1 to IIA2 cervical cancer: a retrospective study. J. Int. Med. Res. 49, 3000605211061008, https://doi.org/10.1177/03000605211061008

Han, D. et al. Impact of D-Dimer for prediction of Incident Occult Cancer in patients with unprovoked venous thromboembolism. PLoS One. 11, e0153514. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0153514 (2016).

Blackwell, K. et al. Plasma D-dimer levels in operable breast cancer patients correlate with clinical stage and axillary lymph node status. J. Clin. Oncol. 18, 600–608. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2000.18.3.600 (2000).

Heit, J. A. Cancer and venous thromboembolism: scope of the problem. Cancer Control 12 Suppl 1, 5–10, https://doi.org/10.1177/1073274805012003S02

Ma, Y. Y. et al. Interaction of coagulation factors and tumor-associated macrophages me diates migration and invasion of gastric cancer. Cancer Sci. 102, 336–342, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1349-7006.2010.01795.x

Johns, C. et al. Aspirin use is Associated with Improved outcomes in Inflammatory Breas t Cancer patients. J. Breast Cancer 26, 14–24, https://doi.org/10.4048/jbc.2023.26.e3

Zhou, Z. et al. An enhanced International Prognostic Index (NCCN-IPI) for patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated in the Rituximab era. Blood 123, 837–842. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2013-09-524108 (2014).

Yu, T., Luo, D., Luo, C., Xu-Monette, Z. Y. & Yu, L. Prognostic and therapeutic value of serum lipids and a new IPI score system based on apolipoprotein A-I in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Am. J. Cancer Res. 13, 475–484 (2023).

Shibutani, M. et al. The significance of the D-Dimer level as a prognostic marker for Survi val and treatment outcomes in patients with stage IV Colorectal Cancer. In vivo (Athens Greece) 37, 440–444, https://doi.org/10.21873/invivo.13097

Ay, C. et al. High D-dimer levels are associated with poor prognosis in cancer patients. Haematologica 97, 1158–1164. https://doi.org/10.3324/haematol.2011.054718 (2012).

Li, W. et al. Prognostic role of pretreatment plasma D-Dimer in patients with solid tumors: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 45, 1663–1676. https://doi.org/10.1159/000487734 (2018).

Liu, B. et al. Prognostic value of pretreatment plasma D-dimer levels in patients with diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL). Clin. Chim. Acta. 482, 191–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cca.2018.04.013 (2018).

Chen, X. et al. Prognostic value of the Preoperative plasma D-Dimer levels in patients with Upper Tract Urothelial Carcinoma in a Retrospective Cohort Study. Onco Targets Ther. 13, 5047–5055. https://doi.org/10.2147/ott.S254514 (2020).

Liu, L. et al. Elevated plasma D-dimer levels correlate with long term survival of gastric cancer patients. PLoS One. 9, e90547. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0090547 (2014).

Morii, T., Mochizuki, K., Tajima, T., Ichimura, S. & Satomi, K. D-dimer levels as a prognostic factor for determining oncological outc omes in musculoskeletal sarcoma. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord 12, 250, https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2474-12-250

Funding

This article was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 81700130).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.S. is the first corresponding author. J.Y. and Z.L. are corresponding authors. X.S., J.Y., and Z.L. designed the outline of this study and reviewed the manuscript. R.S. was the main contributor to collecting the data and writing the first draft. D.M., B.G. and L.Z. prepared the data. L.Z., Q.M., and Y.H. managed the patients. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This retrospective study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University (approval number: 2023KY-13-01) and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shao, R., Meng, D., Gao, B. et al. Evaluation of treatment for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma using plasma D-dimer levels. Sci Rep 15, 3049 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87273-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87273-4