Abstract

Owing to the differences in sedimentary environments in the mining areas of western China, the mechanical properties of rocks in this region are significantly different from those in the central and eastern regions. Therefore, uniaxial cyclic loading-unloading tests were conducted on fine sandstone found in many roof rocks to study the evolution laws of mechanical properties, deformation characteristics, acoustic emission (AE) parameters, and energy under cyclic loading and unloading conditions. The accumulated residual strain, dissipative energy, acoustic emission cumulative ringing counts, and cumulative energy were introduced to characterize the degree of rock damage. Based on this, a piecewise constitutive model was established for fine sandstone. The results indicate that (1) the cumulative ringing counts and cumulative energy of the AE increase in a stepwise manner with an increase in the cyclic loading and unloading times. Still, there is a sudden increase in the plastic failure and post-peak failure stages. (2) The fine sandstone specimens’ input energy, elastic energy, and dissipative energy density increased nonlinearly during the cyclic loading tests. Owing to the closure of the primary pores in the microfracture compaction stage, dominant matrix deformation in the elastic deformation stage, and development and expansion of cracks in the plastic failure stage, with an increase in the cyclic loading and unloading times, the dissipative energy ratio first decreased and then increased. (3) Based on the tangential modulus, residual strain, and Felicity ratio, fine sandstone’s cyclic loading and unloading stress-strain curves were divided into microfracture compaction, elastic deformation, and plastic failure stages. The piecewise constitutive model of fine sandstone constructed with accumulated AE energy was the closest to the real stress-strain curve of the rock, and the deviations of the peak stress and peak strain from the actual situation were 0.52% and 0.84%, respectively. The research results can provide theoretical support for identifying the degree of rock damage in western mining areas and ensure the safe and efficient development of coal resources.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Rock is a material that makes up the Earth’s crust, with many primary cracks in it. The deformation and failure of rock is essentially a process of gradual expansion and polymerization of internal microfractures, which leads to the deterioration of its mechanical properties1,2,3,4. The study of rock deformation and failure processes is important for the safety and stability of engineering structures, particularly in underground and geotechnical engineering. Currently, the mining area in western China has become one of the main coal production bases, and the sedimentary environment in the western mining area has led to significant differences in the mechanical properties of rock masses in this and other areas5,6. Among these, coal-measure sandstone has become the focus of attention in rock mechanics in recent years because of its extensive occurrence and unique properties7,8,9,10,11.

Scholars have studied the process of rock deformation and failure from various aspects to explore the mechanism of rock deformation and failure. The rock constitutive model provides the basis for describing the mechanical properties of rocks and represents the mechanical relationship between the stress and strain during the rock failure process4,11,12,13,14. Laboratory tests are one of the most common methods for obtaining rock damage and failure characteristics and constructing a rock damage constitutive model15,16,17,18,19. Scholars have performed tests such as uniaxial compression, cyclic loading and unloading, and fractional creep and have used methods such as building a hardening damage function20,21,22,23,24, calculating nonlinear compaction deformation, and analyzing plastic failure to describe the damage degree of rock25,26,27,28,29,30. To further improve the accuracy of the damage constitutive model, scholars have defined different types of damage variables to describe the degree of damage to rock specimens, including thermal damage variables, AE energy, dissipative energy proportion, and energy distribution laws, to build damage constitutive models31,32,33,34,35,36,37.

Additionally, considering the difference in the rock initial damage effect and mechanical properties at different stages of the loading process, scholars have established a rock initial damage constitutive model and a piecewise constitutive model that can more accurately reflect rocks’ deformation and failure processes38. For example, Chen et al. proposed a new piecewise constitutive relation composed of the damage and compaction constitutive relations and established the damage statistical constitutive relation of freeze-thaw rocks39. Meng et al. analyzed the AE characteristics and damage model of sandstone, considering the loading rate, and established an initial damage model that can better describe the initial damage characteristics of sandstone specimens40. Based on uniaxial compression experiments, Zhang et al. measured the wave velocity in the compression process using ultrasonic waves, obtained the relationship between strain and wave velocity, defined the wave velocity damage variable based on continuous damage mechanics, and established a piecewise curve constitutive model for rock material damage evolution41.

Researchers have constructed rock damage constitutive equations from different perspectives to deepen our understanding of the basic mechanical properties of rocks, which is of great significance for revealing their deformation and failure mechanisms. However, most rock damage constitutive models used in existing studies have been established based on certain damage variables because the characteristics of rocks at various stages of loading are significantly different. Therefore, to further reveal the damage evolution law of fine sandstone in western mining areas, uniaxial cyclic loading and unloading tests were conducted using fine sandstone from the Buertai Coal Mine in the Shendong Mining area as the research object, and the mechanical properties, energy, acoustic emission evolution characteristics of the rock under cyclic loading and unloading were explored. Based on the dissipative energy, cumulative residual strain, AE cumulative ringing counts, and AE cumulative energy, a piecewise constitutive model of fine sandstone was constructed to provide theoretical support for rock damage degree identification and the safe and efficient development of coal resources in the western mining area.

Specimen preparation and test plan

Specimen preparation

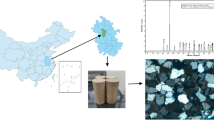

Owing to the good occurrence condition of the coal seam, the thickness of the coal seam is large, the geological structure is small, and the mining intensity is large, which often induces mine earthquakes and rock bursts. The overlying rock structure of the coal seam is an important factor affecting this phenomenon. Therefore, we collected specimens from the 22,207 working face of the Buertai Coal Mine. The dip length of the working face was 302 m, seam thickness was 4.34 m, and seam depth was 319.64 m (Fig. 1). The test specimens were the roof sandstone of the 22,207 working faces of the Buertai Coal mine in the Shendong Mining area, and the lithology was fine sandstone. Before the test, the rock was processed into a φ 50 mm × 100 mm standard cylinder specimen that met the ISRM standard.

Test equipment and scheme

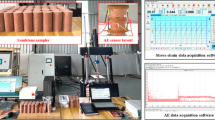

To improve the accuracy of the test results, a KHN-B intelligent ultrasonic automatic wave tester was used to measure the acoustic wave velocities of the rock specimens before testing; this is shown in Fig. 2 (a).

The test system primarily comprised loading and AE monitoring systems (Fig. 2 (b)). The loading system that was used as the RLJW-2000 testing machine. The maximum axial force and axial displacement provided by this equipment are 2000 kN and 100 mm, respectively; the sampling accuracy is ± 1%; and the sampling frequency is 5 Hz42. The AE monitoring system adopted was the AMSY-6 AE system produced by Vallen Company, and the probe model was VS45-H. A resin coupling agent was used to paste the specimen. The preamplifier gain value was 38 dB, the signal excitation threshold value was 40 dB, and the instrument monitoring frequency was 10 MHz.

First, a uniaxial compression test was conducted to assess the basic mechanical parameters of fine sandstone, which provided basic data for the design of cyclic loading and unloading test schemes43. The fine sandstone specimens’ uniaxial compressive strength, peak strain, and elastic modulus were 38.03 MPa, 1.43, and 6.09 GPa, respectively. Second, the cyclic loading and unloading test was performed, the displacement control mode was adopted, the loading and unloading rate was set to 0.25 mm/min, the loading gradient was set to 3kN, and the load was set from 0→3kN→0kN→6kN→0kN→9kN→0kN. It gradually increases until the specimen is destroyed (Fig. 2 (c)). Before the cyclic loading and unloading tests, an AE probe was arranged on both sides of the specimen to collect the AE signals during the loading process.

Analysis of test results

Stress-strain curve and failure morphology

According to the axial stress-strain curve of the cyclic loading and unloading (Fig. 3), the specimen underwent 24 cyclic loading and unloading cycles. The peak strength was 37.85 MPa, and the peak strain was 1.20%. Each cyclic peak stress point is connected to form a cyclic loading and unloading envelope. During this process, the fine sandstone specimens undergo four stages.

-

(1)

Microfracture compaction stage (cycle 0–9 times), in stage I, the axial stress increases in the form of “concave.” The deformation of the specimen at this stage was composed of microfracture compaction and rock matrix deformation, and the primary crack was completely closed at the end of this stage.

-

(2)

Elastic deformation stage (10–20 cycles), in stage II, the axial stress increased approximately linearly. The deformation of the specimen in this stage is dominated by the deformation of the rock matrix, and the deformation of the rock matrix reaches its limit at the end of this stage.

-

(3)

Plastic failure stage (cycle 20–24 times), in stage III, the axial stress increases in a “convex” type, and the deformation of the specimen is gradually dominated by the development of macroscopic cracks, ultimately resulting in a gradual decrease in the bearing capacity of the specimen.

-

(4)

Post-peak failure stage, in stage IV, the specimen was damaged during the post-peak failure stage. The axial stress decreased linearly, and the specimen became brittle.

The failure pattern of the fine sandstone specimen was that of an inclined main crack accompanied by flake spalling at both ends of the crack (Fig. 4). According to the morphology and trend of the fracture surface, the failure of the fine sandstone specimens was dominated by the shear stress. The reason for this phenomenon is that the fine sandstone structure was relatively dense, the adhesion between the rock particles was strong, and the rock particles showed strong tensile properties, which led to dislocation fractures of the rock particles.

Mechanical parameters evolution characteristics

The tangent modulus is a representative parameter reflecting rock deformation characteristics (Fig. 5) derived from the tangent slope in the loading stage44. The tangential modulus of the specimen exhibited a three-stage evolution law with an increase in the number of loading and unloading cycles. In the early loading and unloading stages, the tangential modulus increased approximately linearly owing to the gradual compaction of the microfractures. In the middle stage of loading and unloading, the tangential modulus fluctuated in a steady state as the internal pores of the specimen were compacted and the matrix dominated the rock deformation. In the later stages of loading and unloading, the specimen enters the plastic failure stage, the appearance of macroscopic cracks leads to the degradation of the integrity of the specimen, and the tangent modulus decreases approximately linearly.

Residual strain is the strain that cannot be recovered after the object is removed from an external load (Fig. 6) and reflects the damage inside the rock45. The cumulative residual strain of the specimens followed a three-stage evolutionary law. In the early stages of loading and unloading, the residual strain was dominated by the microfracture compaction of the specimen, and the specimen structure gradually increased with cyclic loading and unloading. The cracks for compression gradually decrease, resulting in an “upward convex” increase in the cumulative residual strain. The specimens entered an elastic deformation stage during the intermediate loading and unloading stages. As the internal microfractures in the specimen were compacted, only the rock matrix underwent elastic deformation during the loading stage. In the unloading stage, the elastic deformation recovered, and no large residual strain was generated. Thus, the cumulative residual strain increases approximately linearly. At the later stage of loading and unloading, cracks occur in the specimen with an increase in load, and the plastic failure cannot be recovered, ultimately resulting in an “upward concave” increase of accumulated residual strain.

AE evolution characteristics

The AE ringing count is the number of transient vibration signals generated by rock specimens under a load and reflects the development of cracks in the specimens46. The evolution law of the AE ringing counts of the fine sandstone specimens is shown in Fig. 7 (a). To better display the evolution process of the AE ringing counts, the ordinate in Fig. 7 (a) is enlarged, as shown in Fig. 7 (b). The AE ringing counts increased and occurred more frequently in the loading stage but hardly in the unloading stage. They reached a peak value when the specimen was damaged. In the early loading and unloading stages, the cumulative AE ringing counts increased slowly, indicating that the step gradient was small and a weak AE phenomenon accompanied microfracture closure. In the middle stages of loading and unloading, the growth rate of the AE cumulative ringing counts increased and exhibited a high step gradient while maintaining stability; this is because the friction between the rock particles primarily generated the AE signals at this stage, and the frequency and intensity of the AE signals were relatively stable. In the later stages of loading and unloading, the growth rate of the cumulative AE ringing counts increased significantly, which manifested as a gradual increase in the step gradient; this is due to the observation that with the increase in loading and unloading times, the specimen structure was damaged, and new cracks developed inside it.

The AE energy is generated by sound waves emitted when a load damages rock specimens and can be used to assess the degree of damage to the specimens. The evolution law of the AE energy of the fine sandstone specimens is shown in Fig. 8(a). To better display the evolution process of the AE energy, the ordinate in Fig. 8 (a) is enlarged, as shown in Fig. 8(b). The AE energy gradually increases with the number of cycles and surges at the moment of destruction. In the early stages of loading and unloading, the cumulative energy of the AE increased slowly as the intensity of the AE signals gradually weakened with the gradual compaction of the microfractures. During the middle stages of loading and unloading, the accumulated AE energy increased linearly as the specimen underwent elastic deformation, and the intensity of the AE signal tended to be stable. During the subsequent loading and unloading stages, the accumulated AE energy rapidly and sharply increased when the specimen was damaged; this is due to the observation that with the increase in cyclic loading and unloading times, the rock structure gradually deteriorates, while the new cracks gradually expand and aggregate to form the main control cracks. The intensities of the AE signals were relatively high, and a large energy release was generated when the specimen was damaged.

Characteristics of energy evolution

In the test, regardless of the heat exchange and damping consumption, a portion of the input energy was stored in the specimen in the form of elastic energy, and the other portion was consumed in the form of dissipative energy through the mutual friction and cracking of rock particles inside the specimen47. As shown in Fig. 9, the fine sandstone specimens’ input energy, elastic energy, and dissipative energy density exhibit nonlinear increasing trends with increasing cyclic loading and unloading times.

At the initial stage of loading and unloading, the total input energy and elastic energy density curves of the specimen increased in the form of “concave.” In contrast, the dissipative energy density curves increased linearly. The dissipative energy density of the specimen in the early stages was higher than the elastic energy density (Fig. 10), whereas the opposite was true in the later stages; this was because the stress gradients of cyclic loading and unloading in the early stages were small, and the primary cracks inside the specimen rubbed or closed with each other, ultimately consuming most of the energy. During the middle stages of loading and unloading, the specimen’s input energy, elastic energy, and dissipative energy density increased linearly, and the growth rate increased from high to low in the order of the input energy density, elastic energy density, and dissipative energy density. At this stage, the elastic energy density is greater than the dissipative energy, indicating that the internal structure of the specimen is relatively dense, the degree of damage tends to be stable, and most of the input energy is converted into elastic energy. In the later stages of loading and unloading, the specimen’s input energy and elastic energy density increased linearly.

In contrast, the dissipative energy density increased in an “upward concave” manner. At this stage, the proportion of the dissipative energy density gradually increased, but the elastic energy density still dominated. Subsequently, with an increase in the number of cyclic loading and unloading cycles, the specimen generated new cracks that gradually developed, resulting in a decrease in the rate of increase in the elastic energy density and a gradual increase in the growth rate of the dissipative energy density.

Establishment of piecewise constitutive damage model

Comparison of constitutive equations at different loading stages

To analyze the deformation and failure characteristics of fine sandstone during cyclic loading and unloading, the Kaiser effect and Felicity ratio were introduced to divide the different stages of the cyclic loading and unloading curves. The Kaiser effect is a phenomenon in which emissions rarely occur when the load does not exceed the maximum of the previous load when the specimen is loaded and reloaded after unloading48. The definition of the Felicity ratio can be expressed by Eq. (1).

FRi is the Felicity ratio in the ith cycle, and Pi+1 is the stress level when a large amount of AE occurs during the i + 1 loading process. Pimax exhibits the highest stress level for load i.

The Felicity ratios of the fine sandstone specimens decreased in a piecewise manner as the number of cycles increased (Fig. 11). At the initial stage of loading and unloading, the Felicity ratio decreases in a “concave” pattern and is greater than 1, indicating that the Kaiser effect is effective and that the AE phenomenon at this stage is primarily caused by the closure of microfracture in the rock. The damage degree of the specimen is small. In the middle stage of loading and unloading, the Felicity ratio was stable at approximately 1, and the Kaiser effect was evident, indicating that the friction between rock particles primarily caused the AE phenomenon at this stage. In the later loading and unloading stages, the Felicity ratio decreased linearly to less than 1, and the Kaiser effect failed; this indicates that the internal cracking of the rock primarily caused the AE phenomenon at this stage. Irreversible damage occurred in the specimen, and the degree of damage gradually increased as the cyclic loading and unloading progressed.

According to the above analysis, the deformation and failure processes of the fine sandstone specimens are relatively complex, and a simple damage constitutive equation cannot accurately reflect the stress-strain evolution law. Based on the tangential modulus, cumulative residual strain, and evolution law of the Felicity ratio, the loading process of the fine sandstone samples was divided into three stages: microfracture compaction, elastic deformation, and plastic failure (Table 1).

In the microfracture compaction stage, the cumulative residual strain, dissipative energy, AE cumulative ringing counts, and cumulative energy of fine sandstone reflect the compaction deformation process of the rock to a certain extent. The constitutive equation of this stage can be expressed by Eq. (2).

C is the compaction variable, 0 is when the specimen is not compressed, 1 is when the specimen is fully compacted, and Ef is the tangential modulus of the fine sandstone specimen during microfracture compaction.

Compaction variables were defined based on the cumulative residual strain, dissipative energy, cumulative AE ringing counts, and cumulative energy. The evolution laws of the compaction variables are shown in Fig. 12, and the fitting functions are listed in Table 2. The compaction variables were defined based on the four parameters and increased gradually with axial strain. The compaction variables defined according to the accumulated residual strain and dissipative energy exhibit a nonlinear upward trend. In contrast, those defined according to the accumulated AE ringing counts and accumulated energy exhibit an approximately linear increase.

The fitting function was introduced into Eq. (2) to obtain the constitutive equation of the fine sandstone microfracture compaction stage constructed based on different parameters, as shown in Fig. 13. The fitting functions are listed in Table 2. Constitutive models based on different parameters can approximately reflect the stress-strain curve morphology of the microfracture compaction stage in fine sandstone. Additionally, the constitutive model based on the accumulated AE energy exhibited the highest correlation with the original test data (correlation coefficient = 0.976). In contrast, the constitutive model based on the dissipative energy exhibited the lowest correlation (0.898). Therefore, the constitutive model based on the accumulated AE energy can more accurately reflect the stress-strain evolution law in the microfracture compaction stage of fine sandstone.

In the elastic deformation stage, the internal microfractures of the fine sandstone specimen are completely compacted, and the deformation of the specimen under load is composed only of the elastic deformation generated by the rock matrix, which can be directly expressed by Hooke’s law, as shown in Eq. (3).

where σcf. is the axial stress at the end of the microfracture compaction stage, εcf. is the axial strain at the end of the microfracture compaction stage, and Ee is the tangent modulus of the cyclic loading and unloading envelopes during the elastic deformation stage.

In the plastic failure stage, damage began to appear in the fine sandstone specimen, and the damage constitutive equation can be expressed as Eq. (4).

where D is the damage variable; 0 is considered when the specimen is damaged without damage, and 1 is considered when the specimen is completely damaged. Ep is the tangent modulus of the cyclic loading and unloading envelopes during the plastic failure stage, σce is the axial stress at the end of the elastic deformation stage, and εce is the axial strain at the end of elastic deformation.

The evolution law and fitting function of the damage variables defined based on different parameters, along with the axial strain, are shown in Fig. 14, and the fitting functions are listed in Table 3. The damage variables were defined based on the dissipative energy increase approximately linearly. In contrast, the damage variables were defined based on the cumulative residual strain, cumulative AE ringing counts, and cumulative energy increase nonlinearly. The growth rate increased with increasing axial strain.

To further improve the damage constitutive model’s accuracy, a damage correction coefficient was introduced to modify Eq. (4), and the revised equation is represented in Eq. (5).

where δ is the damage correction factor.

The correction coefficient was defined according to the elastic modulus of the envelope at the loading stage and the tangential modulus at the unloading stage, as shown in Eq. (6).

where El is the elastic modulus at the loading stage of the cyclic loading and unloading envelope, and Eu is the tangential modulus at the unloading stage of the cyclic loading and unloading envelope.

The damage constitutive equations for the fine sandstone specimens constructed based on different parameters in the plastic failure stage are shown in Fig. 15, and the fitting functions are listed in Table 3. Damage constitutive models constructed with different parameters can approximately reflect the stress-strain characteristics of fine sandstone specimens in the plastic failure stage. Additionally, the damage constitutive model based on the cumulative AE ringing counts exhibited the highest correlation with the test data, with a 0.998 correlation coefficient. In contrast, the damage constitutive model based on the dissipative energy exhibited the lowest correlation, with a 0.905 correlation coefficient. Therefore, the damage constitutive model based on the AE cumulative ringing counts can accurately reflect the stress-strain evolution law of fine sandstone specimens during the plastic failure stage.

Construction and verification of a piecewise constitutive damage equation

Based on previous research results, a piecewise constitutive equation for the cyclic loading and unloading fine sandstone specimens was constructed by combining the constitutive equations for microfracture compaction, elastic deformation, and plastic failure. Equation (7) is the basic form of the piecewise damage constitutive equation, and Eq. (8) is the piecewise damage constitutive equation for a fine sandstone specimen.

The piecewise damage constitutive equation is shown in Fig. 16. The combined piecewise constitutive model better reflected the deformation and failure processes of the sandstone specimens in the Shendong mining area, with a Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.999. The peak stress and strain were 37.99 MPa and 1.2%, with errors of 0.52% and 0.84%, respectively. In summary, the three stages of microfracture compaction, elastic deformation, and plastic failure of the rock specimens based on the accumulated AE energy, Hooke’s law, and AE cumulative ringing counts best reflect the deformation and failure processes of the fine sandstone specimens.

Discussion

The basic mechanical characteristics and AE evolution laws of fine sandstone specimens from mining areas in western China were obtained through laboratory tests. To further understand the deformation and failure law of the rock, a piecewise constitutive model was constructed based on the cumulative residual strain, dissipative energy, and acoustic emission parameters. The construction process of piecewise constitutive model is shown in Fig. 17. Compared with other constitutive models, the piecewise constitutive model constructed in this study has the following advantages:

-

(1)

This study combines a theoretical derivation with actual test parameters. Compared to the traditional purely theoretical constitutive model, the piecewise constitutive model constructed in this study is more realistic.

-

(2)

Multiple test parameters defined the compaction and damage variables. Compared with the constitutive model constructed with a single test parameter, the test parameters that best reflected the compaction and damage degrees of the rock specimens were selected in this study. The constructed piecewise constitutive model can more accurately reflect the deformation and failure processes of the rock specimens.

-

(3)

The deformation and failure processes of the rock specimens were divided into three stages, and the corresponding constitutive models were constructed according to each stage’s different deformation and failure characteristics. Compared with the constitutive model, the piecewise constitutive model constructed in this study was more consistent with the rock specimens’ actual deformation and failure laws.

Although the piecewise constitutive model in this study has the above limitations, it also has some shortcomings. For example, there are fewer test specimens, only four test parameters are analyzed when building the piecewise constitutive model, and the cumulative AE ringing counts can better reflect the damage degree of the rock specimens. In the future, we plan to conduct tests on other rock specimens and analyze parameters, such as wave velocity and speckle, to further explore rocks’ deformation and failure characteristics.

Conclusion

-

(1)

The cyclic loading and unloading of fine sandstone specimen in China’s western mining area has experienced four stages: microfracture compaction, elastic deformation, plastic failure and post-peak failure. The peak stress is 37.85 MPa, the peak strain is 1.2%, and the failure mode is the crack caused by shear stress, and the fragmentation occurs at both ends of the crack.

-

(2)

With the increase of cyclic loading and unloading times, the tangential modulus showed an evolutionary trend of first increasing, then stabilizing and then decreasing, the cumulative residual strain continued to increase, and the growth rate first decreased and then increased, the cumulative ringing counts and cumulative energy of AE both increased slowly, and a sudden increase occurred in the plastic failure and post-peak failure stage, and the input energy, elastic energy and dissipative energy density showed a nonlinear increase trend. The proportion of dissipative energy decreases first and then increases, while the elastic energy is opposite.

-

(3)

Based on the tangent modulus, cumulative residual strain and Felicity ratio, the cyclic loading and unloading stress-strain curves of fine sandstone specimen are divided into microfracture compaction stage (0-0.74%), elastic deformation stage (0.74–1.06) and plastic deformation stage (1.06-failure). The piecewise constitutive model of fine sandstone constructed with accumulated AE energy is closest to the real stress-strain curve of rock, and the deviation of peak stress and peak strain from the actual situation is 0.52% and 0.84%, respectively.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are avail-able from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Zhang Ke, X., Yi, Z., Kai, B., Rui, F. & Wenchen Quantitative characterization of the failure behavior of dangerous rocks based on the frozen-thawing test. Sci. Rep. 13(1), 10476 (2023).

Tongbin, Z., Pengfei, Z., Weiyao, G., Xufei, G., Chao, W., & Yang, C. Controlling roof with potential rock burst risk through different pre-crack length: mechanism and effect research. J. Cent. South. Univ. 29(11), 3706–3719 (2022).

Xulong, Y., Zhen, L., Yanbo, Z., Zhigang, T. & Peng, L. Effect of regionalized structures on rock fracture process. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 10490 (2024).

Wei, Z., Weiyao, G., Zhiqi, W. Influence of lateral pressure on mechanical behavior of different rock types under biaxial compression. J. Cent. South. Univ. 29(11), 3695–3705 (2022).

Heijian, Y., Guangli, G., Huaizhan, L., Tiening, W. & Yafei, Y. Prediction method and research on characteristics of surface subsidence due to mining deeply buried jurassic coal seams. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 81(10), 449 (2022).

Li, A. et al. Physical simulation study on grouting water plugging of flexible isolation layer in coal seam mining. Sci. Rep. 12(1), 875 (2022).

Tongbin, Z., Pengfei, Z., Yaxun, X., Weiyao, G., Yulong, Z., Feng, Z. X. Master crack types and typical AE characteristics during rock failure. Int. J. Coal Sci. Technol. 10(1), 1–14 (2023).

Wei, Z., Baoliang, Z., Tongbin, Z. Study on the law of failure acoustic–thermal signal of weakly cemented fractured rock with different dip angles. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 56(6), 4557–4568 (2023).

Weihui, P. et al. Coal burst prevention technology and engineering practice in ordos deep mining area of China. Sustainability 15(1), 159 (2022).

Wei, Z., Tongbin, & Xutao, Z. Stability analysis and deformation control method of swelling soft rock roadway adjacent to chambers. Geomech. Geophys. Geo-Energy Geo-Resour 9(1), Paper ID: 91. (2023).

Xiangjun, C., Liyang, L., Lin, W., & Lingling, Q. The current situation and prevention and control countermeasures for typical dynamic disasters in kilometer-deep mines in China. Saf. Sci. 115, 229–236 (2019).

Wei, Z., Minglu, X., Weiyao, G. Study on fracture characteristics of anchored sandstone with precast crack based on double K criterion. Int. J. Solids Struct. 275, Paper ID: 112296. (2023).

Zixu, W., Junhong, H., Yanglong, C., Xinping, L., Tingting, L., Fei, M. Dynamic mechanical properties of different types of rocks under impact loading. Sci. Rep. 13(1), 19147 (2023).

Shuqian, D., Shihao, L., Jiecheng, X., Dingping, X., Laibiao, X., Xiqing, J., Minghuan, Z., Guofeng, L. Investigation on uncoordinated deformation and failure mechanism and damage modeling of rock mass with weak interlayer zone. Eng. Fail. Anal. 163, 108563 (2024).

Tianbai, Z., Yueping, Q., Qiufeng, M., & Jia, L. A constitutive model for rock based on energy dissipation and transformation principles. Arab. J. Geosci. 12(15), 492 (2019).

Fengqiang, G., Peilei, Z., & Lei, X. Damage constitutive model of brittle rock under uniaxial compression based on linear energy dissipation law. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 160, 105273 (2022).

Yu, D., Enlong, L., Bo, X., Yunyong, H., Fei, L., Chuan, H. A micro–macro constitutive model for rock considering breakage effects. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 33(02), 173–184 (2023).

Song, C., Sheng, Q. C., Qing, Y., Khan, & Ullah, M. Comparative study on three-dimensional statistical damage constitutive modified model of rock based on power function and Weibull distribution. Environ. Earth Sci. 77(3), 108 (2018).

Wei, Z., Xiuzhi, W., Minglu, X., & Baoliang, Z. Theoretical and experimental study on the mechanical measurement of rock tensile fracture by ring radial compression. Géotechnique, (2024).

Cerfontaine, B. & Collin, F. Cyclic and fatigue behaviour of rock materials: review, interpretation and research perspectives. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 51(2), 391–414 (2018).

Binyu, L., Yicheng, Y., Nanyan, H., Weiqi, W. Investigation of dip effect on uniaxial compressive strength of inclined rock specimen by experimental and theoretical models. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 53(12), 5659–5675 (2020).

Cheng, L., Chao, M., Hangyu, D., Ping, Z., Deng, X., Chao, L., Chengxing, Z. A creep model for salt rock considering damage during creep. Mech. Time-Dependent Specimens. 28(1), 255–272 (2024).

Wei, Z., Zhuo, Q., Wanrong, L., Baoliang, Z., Weiyao G. Study on the AE characteristics and energy evolution mechanism of sandstone with different aspect ratios under biaxial compression. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 57(11), 9019–9034 (2024).

Xu, T., Fu, M., Yang, S., Heap, M. J., Zhou G. A numerical meso-scale elasto-plastic damage model for modeling the deformation and fracturing of sandstone under cyclic loading. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 54(9), 4569–4591 (2021).

Wei, Z., Qing, M., Xiaoli, L., Enzhi, W., Weiqiang, X., Danqing, D. Study on crack propagation mechanism and acoustic-thermal sensitivity analysis of pre-cracked weakly cemented rock. Theoret. Appl. Fract. Mech. 133, 104619 (2024).

Jielin, L., Longyin, Z., Keping, Z., Hui, C., Le, G., Yun, L., & Yanjun, S. Non-linear creep damage model of sandstone under freeze-thaw cycle. J. Cent. South. Univ. 28(3), 954–967 (2021).

Shuqian, D. et al. Constitutive modeling of weak interlayer zone subject to unloading stress paths in underground excavation based on modified equivalent plastic work. Eng. Fail. Anal. 160, 108179 (2024).

Faradonbeh, R. S., Taheri, A. & Karakus, M. Failure Behaviour of a Sandstone subjected to the systematic cyclic loading: insights from the double-criteria damage-controlled test method. Rock. Mech. Rock. Eng. 54 (11), 5555–5575 (2021).

Wei, Z, Wanrong, L., Xutao, Z. Study on crack propagation characteristics of rocks with different lateral pressure based on joint monitoring of DIC and AE. Geomech. Geophys. Geo-energy Geo-resources, 10(1), Paper Id 132 .

Xuesheng, L., Jianguo, N., Yunliang, T., & Qingheng, G. Damage constitutive model based on energy dissipation for intact rock subjected to cyclic loading. Int J Rock Mech. Mining Sci., 85, 27–32 (2016).

Xiaobin, Y., Hongming, C., Xin, H., Chaogang, N., Jiaqi, L. Research on characteristic stress and constitutive equation of confined sandstone during damage evolution based on energy evolution analysis. Adv. Specimens Sci. Eng, 2019, 1–13. (2019).

Wei, Z., Baoliang, Z., & Weiyao, G. Study on the mechanism of energy evolution and bearing degradation in pre-cracked sandstone under non uniform cyclic loading. Theoret. Appl. Fract. Mech. 132, 104472 (2024).

Zhu Chun, K. et al. Volumetric deformation and damage evolution of Tibet interbedded skarn under multistage constant-amplitude-cyclic loading. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 152, 105066 (2022).

Guijie, Z., Chen, C., & Huan, Y. A thermal damage constitutive model for Oil Shale based on Weibull Statistical Theory. Math. Probl. Eng. 2019, 1–11 (2019).

Min, D., Zizheng, Z., Weijian, Y., Jinlin, X., & Shiqiang, X.. Acoustic emission characteristics and damage law for prefabricated single-crack sandstone under uniaxial compression. Struct. Control Health Monit., 29(10) (2022). [2024-07-14].

Yifan, C., Hang, L., Shijie, X., Rihong, C., Shuwei, S., Wenhua, Z., Yixian, W., Yanlin, Z., & Huihua, H. Fracture closure empirical model and theoretical damage model of rock under compression. Specimens 16(2), 589 (2023).

Shuqian, D., Po, G., Dingping, X., Bei, C., Guofeng, L., Quan, J., Shili, Q., & JieCheng, X. A new perspective on the semi-quantitative meso-structural failure mechanism of deep weak interlayer zone under different stress paths. Rock. Mech. Rock. Eng. 57(5), 3171–3195 (2024).

Shijie, X., Zhenyu, H., & Tao, Z. A semiempirical constitutive relationship for rocks under uniaxial compression considering the initial damage recovery. Fatigue Fract. Eng. Specimens Struct. 46(4), 1300–1313 (2023).

Yifan, C., Hang, L., & Rihong, C. Damage constitutive model considering nonlinear fracture closure of rock under freezing–thawing cycles. Environ. Earth Sci. 82 (1), 4 (2023).

Shuqian, D., Jian Quan, X., & Dingping, L.G. Experimental study of mechanical behavior of Interlayer Staggered Zone under Cyclic Loading and Unloading Condition. Int. J. Geomech. 20(3), 04019187 (2020).

Jinhao, Z., Hongkai, C., He, W., & Zheng, Z. Experimental study on damage evolution characteristics of rock-like material. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 44(10), 8503–8513 (2019).

Dongxiao, Z., Qing, W., Weiyao, G., Lexin, C., Yujing, J., & Yongqiang, Z. The influence of infilling specimen strength on mechanical properties and failure mechanism of fractured sandstone. Fatigue Fract. Eng. Specimens Struct. 46(12), 4512–4524 (2023).

Chen, C., Xu, T., Zhou, G. & Qin, T. Experimental investigation of influence of alternating cyclic loadings on creep behaviors of sandstone. Mech. Time-Dependent Mater. 25 (1), 1–19 (2021).

Huaizhong, L., Jianliang, P., Jianfeng, L., Mingli, X., Li, Z., & Hongqiang, X. Influence of volume compression on the unloading deformation behavior of red sandstone under damage-controlled cyclic triaxial loading. J. Rock. Mech. Geotech. Eng. 15 (5), 1200–1212 (2023).

Zhixi L, & Xiaodie L. Evolution of residual strain and strain energy in rocks under various types of uniaxial cyclic loading-unloading. Front. Earth Sci. 11, 1243909 (2023).

Liu Xingzhi, Z., Songhang, X. & Yongkang, W. T. Three-dimensional heterogeneity of the Pore and Fracture Development and Acoustic Emission Response Characteristics of Coal Rocks in the Yunnan Laochang Block. Energies 17(5), 1207 (2024).

Bingqian, Y. et al. Study on damage anisotropy and energy evolution mechanism of jointed rock mass based on energy dissipation theory. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 82 (8), 294 (2023).

Zhao Kui, Z. et al. Cyclic impact damage and water saturation effects on mechanical properties and kaiser effect of red sandstone under uniaxial cyclic loading and unloading compression. Rock. Mech. Rock. Eng. 57(1), 181–195 (2024).

Funding

The research described in this paper was financially supported by State Key Laboratory of Water Resource Protection and Utilization in Coal Mining (GJNY-21-41-17), National Natural Science Foundation of China (52304095), Shandong Key Laboratory of Mining Disaster Prevention and Control, Shandong University of Science and Technology (SMDPC202301), Hebei Natural Science Foundation (E2023508026).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Q.W and D.Z wrote the main manuscript and F.H and P.Z prepared figures Y.Z and F.X provide the basic data.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Q., Zhang, D., Han, F. et al. Mechanical properties and piecewise constitutive model of fine sandstone in mining area of western China. Sci Rep 15, 3687 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87295-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87295-y

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Study on the energy characteristics of rocks under cyclic loading and unloading

Scientific Reports (2025)