Abstract

In this study, the proposed method involves the confident insertion of π-spacer fragments between donor and acceptor parts of a newly designed (A1-D-A2) molecule into the reference molecule (PP2). Frontier molecular orbitals study using MPW1PW91/6-31G(d,p) level of DFT demonstrates that all designed molecules possess a lower band gap (2.62–3.35 eV) in comparison to R (3.77 eV). The absorption properties clearly show that all the designed molecules (DD1–DD8) have higher absorption values (434.44–566.40 nm) in the gas phase and (498.65–624.01 nm) in the solvent phase compared to R values of 380.32 nm in the gas phase and 415.61 nm in the solvent phase. Significant LHE values and the lowest λe values (0.0062–0.0110 eV) are observed in the designed molecules. This study will help researchers to design molecules for the development of efficient PSCs devices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The use of fossil fuels has led to climate extremes such as heatwaves, forest fires, rising sea levels and flooding1,2. The Paris Accord, ratified in 2015, affirmed the right to a safe environment by protecting humanity from the negative effects of climate change caused by the inefficient and often inappropriate use of fossil fuels3. To limit the global temperature rise, as outlined in the agreement, a reduction in greenhouse gas emissions, ideally to zero, is essential. For this reason, renewable energy sources such as solar energy4,5, wind energy6, hydropower7 and geothermal energy8 are being intensively researched as environmentally friendly and economical options9. Solar energy is attracting great interest worldwide due to its low-cost, high-energy content and universal availability10,11,12,13,14. Energy production is expected to increase by 48% by 2050, supported by global economic and industrial progress. Building integrated photovoltaic (BIPV) technology seamlessly transforms existing building components, such as walls, roofs, and windows, into photovoltaic systems. BIPV has proven to be a promising alternative for the introduction of photovoltaics in urban locations where space is at a premium. BIPV technology has attracted a lot of attention since 2000 due to its potentially positive impact on zero-energy buildings. The use of a luminescent solar concentrator (LSC) is an effective and reliable technique for generating electricity from sunlight. LSC is a translucent polymer or glass laminated or coated with a fluorophore that can absorb and re-emit sunlight15. The LSC efficiently captures sunlight and directs it through total internal reflection (TIR) into the material until it reaches the edge, where a silicon solar cell captures the captured light and converts it into electricity16. LSC technology undoubtedly offers significant advantages for BIPV systems17,18,19. Unlike other BIPV systems, LSC offers unparalleled design flexibility and can be seamlessly integrated into various building components such as windows, car roofs, sound barriers, and greenhouses20. The versatility of LSC includes design freedom, geometry and colour options for smooth installation. Extensive work has been carried out on LSCs since the 1970s. However, their commercial applicability is limited due to light loss phenomena such as re-absorption losses21,22, escape cone losses, low photostability23,24,25, aggregation-induced quenching (ACQ)26 and low photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY)27. In response to these issues, researchers have focused on fluorophores like organic dyes28, quantum dots29, carbon dots30, metal complexes31, aggregation-induced emitting fluorophores (AIEgen)26, and fluorescent proteins32. Furthermore, the research investigates designs such as plasmonic LSCs33, fibre structures34, and multilayer LSCs35.

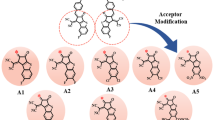

In this study, the same π-spacer (benzene) was used but different acceptor units were employed to optimize the optoelectronic properties. To enable a comparison between the designed molecules (DD1–DD8) and the reference molecule (PP2)36, the latter was renamed R. Figure 2 shows the computationally analyzed molecules (DD1–DD8). The acceptor units used in the current study have already been used by various experimental research groups37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44. The designed molecules have been shown to significantly increase the efficiency of PSCs. All the designed compounds show exceptional potential for photovoltaic and optoelectronic applications. These properties include a significantly reduced band gap and highly efficient light absorption. All designed compounds developed are suitable for the production of efficient pyrrolopyrazine-based organic solar cells. Moreover, a comprehensive investigation was carried out to determine the charge assignment between the donor and acceptor units.

Computational methodology

Gaussian 0945 was used to generate the output files after processing the input files. Six functionals such as B3LYP46, CAM-B3LYP47, MPW1PW9148, ωB97XD49, M0650 and M06-2X51 at 6-31G (d,p) are used in Gaussian 09 to perform DFT calculations. It is important to select the most suitable functional. The reference molecule (R) was processed with different functionals. The purpose of using different functionals is to improve the accuracy of the work. Different functionals provide different values. Selecting a method that gives results that most closely match with published experimental results for R can improve the accuracy of the results. Gauss View 5.0.852 software was used to visualize the results obtained as a result of computational processing by Gaussian 09 software. The reference molecule (R) was optimized with different density functionals of DFT in the first step of the work. For a detailed study of its spectra and other optoelectronic properties, R was further processed after optimization. Chloroform (CH3Cl) was chosen as the solvent. The CPCM solvation approach53 was used in conjunction with the TD-SCF approach for the solvent phase calculations. The results were compared with the experimental values of R. Analyses of the UV–vis λmax of all density functionals in the excited (S1) state showed a strong correlation between the maximum absorption coefficient (λmax) value of the MPW1PW91 functional and the experimental (λmax) value of R. The MPW1PW91 density functional gave the value closest to the experimental λmax of R. It is concluded that the MPWIPW91 functional is suitable for further exploration of designed compounds (DD1–DD8). Density of States (DOS) analysis and Transition Density Matrix (TDM) analysis were used to verify the results obtained from the above steps. The DOS analysis was used to investigate the role of the different components (acceptor and donor) in light absorption. PyMOlyze-1.1 software54 was used to visualize the data. Transition Density Matrix (TDM) data were analyzed using the Multiwfn 3.7 wave function analyzer55. For efficient charge transfer, the internal reorganization energy plays a crucial role. The reorganization energy of the electrons and holes was evaluated using the following equations:

\(E_{ - }\) and \(E_{ + }\) represent the anionic and cationic energies, respectively, derived from optimized anionic and cationic molecules. \(E_{o}\) refers to the ground state energy of the optimized neutral molecule, while \(E_{o}^{ + }\) and \(E_{o}^{ - }\) represent the anion and cation energies computed from the molecular geometry of the cationic and anionic structures in the neutral condition, respectively. Moreover, \(E_{ + }^{o}\) and \(E_{ - }^{o}\) denote the energy of the neutral molecule obtained by optimizing the cationic and anionic geometry, respectively.

Results and discussion

The aim of this study was to enhance the pyrrolopyrazine core featuring dimethylamine (donor) and two cyano (acceptor) by latent acceptor units, and at the same time to precisely determine optical and electronic properties. The PP2 derivative (designated R) with a pyrrolopyrazine core and donor–acceptor moieties, which has been experimentally synthesized, is a reliable basis for the creation of new molecules. The R molecule consists of two parts: (i) pyrrolopyrazine with a dimethylamine (donor) and (ii) an acceptor with two cyano groups (acceptor). The end-capped modification of the dimethylamine donor unit is crucial in achieving superior optoelectronic properties. By replacing the dimethylamine moiety of the donor group on one side with a bridge and alternative acceptor groups, eight new organic materials (DD1–DD8) with excellent photovoltaic properties were constructed.

The R molecule at the DFT/6-31G (d,p) level was first optimized with six different functionals (B3LYP, CAM-B3LYP, MPW1PW91, ωB97XD, M06 and M06-2X). The optimized R was then analyzed with the CPCM model in the CH3Cl solvent employing UV–vis spectroscopy. The absorption maxima of the R in CH3Cl solvent were confidently measured at 430.69 nm, 340.42 nm, 409.16 nm, 322.65 nm, 409.6 nm, and 344.31 nm using functionals B3LYP, CAM-B3LYP, MPW1PW91, ωB97XD, M06 and M06-2X, respectively. Figure 1 demonstrates the reported and calculated λmax of R at different basis sets. Notably, an absorption peak at 406 nm was experimentally observed. MPW1PW91/6-31G (d,p) was selected for further investigation due to its proximity to the experimentally measured absorption maximum value. The DFT functional was selected and used to optimize the R and all designed molecules (DD1–DD8) at their ground state.

Bar chart of the R with six distinct functionals in a chloroform solvent at various functionals by using Origin 8.5 version (https://www.originlab.com). All output files for the studied compounds were generated using Gaussian 09 version D.01 (https://gaussian.com/g09citation).

As shown in Fig. 2, the designed compounds (DD1–DD8) have a stable planar geometry with reduced steric hindrance and increased charge carrier mobilities.

As depicted in Fig. 3, the optimized geometries of R and (DD1–DD8) validate that all molecules have a planar shape. To assess the influence of the bridge (benzene) and acceptor units, the dihedral angles of all developed molecules (DD1–DD8) and R on one side of the molecules were calculated using optimized structures. Figure 3 displays the resulting dihedral angles (Φ) of all developed (DD1–DD8) molecules. The conjugation, structural planarity, optical and electronic properties of the designed structures (DD1–DD8) are significantly improved by modifying the donor group with bridge and acceptor moieties. The modification of the donor group with bridge and acceptor moieties is also crucial for determining the charge transport capabilities and the reorganization energies of the materials.

Systematic optimized geometry of R, DD1–DD8 molecules are made with the help of Gauss View 5.0 (https://gaussview.software.informer.com) and Gaussian 09 version D.01 (https://gaussian.com/g09citation).

Frontier molecular orbitals

Frontier molecular orbitals (FMOs) comprise the highest molecular orbital (HOMO) and unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO). It is important to understand the FMO because it explains the process of charge transfer from the ground state to the excited state. Electrons occupy the HOMO in the ground state and move to higher orbitals when they receive energy from photons. Excitation causes the electrons to shift from the HOMO to the LUMO, which accepts these excited electrons. The optoelectronic properties of molecules, including excitation energy, optical absorption, charge density and charge transport, are directly influenced by the energy gap (Eg) between the HOMO and the LUMO. Molecules with a reduced band gap exhibit high reactivity, softness, and a high ratio of charge transfer within the molecule. The effect of incorporating a pi-linker and different acceptor subunits on the pyrrolopyrazine core was investigated using the MPW1PW91/6-31G(d,p) DFT method to determine the HOMO-LUMO energy levels and associated band gaps.

To achieve efficient charge transfer, it is necessary to concentrate the HOMO energy level over the donor region and disperse the LUMO over the acceptor moieties. The HOMO energy level of the reference is spread over the donor region and the core, as shown in Fig. 4. The acceptor moieties host the entire LUMO. The charge density distribution observed in the reference molecule is probably due to its planar configuration. It is worth noting that the designed molecules (DD1–DD8) exhibit a concentrated HOMO charge density in the donor regions and a spread LUMO charge density in the acceptor regions. This results in an enhanced charge transfer ability compared to the R. The distribution of charge density across the recently added bridges in the examined FMOs of the newly developed compounds (DD1–DD8) demonstrates their involvement in charge transfer.

HOMO LUMO distribution pattern of R, DD1–DD8 at MPW1PW91/6-31G(d,p) DFT level. The pictures were drawn with software Avogadro Version 1.2.0 (http://avogadro.cc/). All output files of studied compounds were made using Gaussian 09 Version D.01 (https://gaussian.com/g09citation).

Figure 4 shows the energy values associated with the HOMO-LUMO orbitals and their band gaps. The R molecule has a bandgap of 3.77 eV, while designed molecules (DD1–DD8) have a reduced bandgap ranging from 2.62–3.35 eV. The designed molecules (DD1–DD8) follow a sequence of band gaps: DD3 < DD1 < DD2 < DD4 < DD5 < DD8 < DD6 < DD7 < R. These results show a significant decrease in the band gap for the designed molecules compared to R, indicating their potential for practical applications. DD3 has the smallest band gap, which strongly promotes the movement of charges within the molecule and contributes to its broad absorption spectrum. The reduced band gap is likely due to the presence of strongly electron-attracting acceptor groups (2-(5,6-dichloro-2-methylene-3-oxo-2,3-dihydro-1H-inden-1-ylidene) malononitrile). It is proposed that the designed molecules (DD1–DD8) will exhibit improved optoelectronic properties due to their reduced band gap to R.

Optical properties

UV–vis analysis was performed at the MPW1PW91/6-31G (d,p) DFT level in the gas phase and in the organic solvent chloroform to evaluate the optical and photophysical properties of the R molecule and the newly designed (DD1–DD8) compounds. Tables 1 and 2 contain the gas phase and solvent data for the maximum absorption wavelength (λmax), transition energy (Ex), oscillator frequency (fos), and assignments that explain the nature of transitions in the designed (DD1–DD8) and R molecule. The experimental measurement of λmax of R is 406 nm, while DFT calculations give values of 380.32 nm and 415.61 nm in the gas and chloroform phases, respectively. It was found that DD3 had the highest absorbance value of all eight studied molecules (DD1–DD8), measuring 566.40 nm in the gas phase and 624.01 nm in the CH3Cl solvent. This was attributed to the endcap moiety (2-(5,6-dichloro-2-methylene-3-oxo-2,3-dihydro-1H-inden-1-ylidene) malononitrile), which caused the spectrum to be red-shifted and enhanced the photoelectric properties of PSCs.

Typically, to enhance the photoelectric properties of PSCs, the absorption spectrum is usually shifted towards the red end of the visible-light spectrum. DD1–DD8 molecules achieve this by substituting a side-chain donor unit with a range of end-capped acceptor units in the R molecule, as shown in Fig. 5. The λmax of the designed molecules (DD1–DD8) are 553.13 nm, 546.91 nm, 566.40 nm, 493.76 nm, 489.03 nm, 462.28 nm, 434.44 nm, and 477.74 nm in gaseous phase. The decreasing order of λmax values of all compounds is noted as: DD3 > DD1 > DD2 > DD4 > DD5 > DD8 > DD6 > DD7 > R in the gas phase. All designed molecules (DD1–DD8) show a redshift in the λmax values, which is due to the excellent stability of delocalized e- in the gas phase. DD3 shows the highest λmax value in the gaseous state. It can be concluded that all designed molecules are the best chromophores.

On the other hand, the λmax of designed molecules (DD1–DD8) in chloroform solvent are 605.81 nm, 599.68 nm, 624.01 nm, 530.78 nm, 534.44 nm, 498.65 nm, 463.44 nm, and 516.28 nm respectively. The λmax values demonstrate the performance of the acceptor units for DD1–DD8 designed molecules. The decreasing order of λmax values of all compounds is as follows: DD3 > DD1 > DD2 > DD5 > DD4 > DD8 > DD6 > DD7 > R in the chloroform solvent. All designed molecules (DD1–DD8) show a red shift of λmax due to the exceptional stability of delocalized electrons in the chloroform solvent. DD3 exhibits the highest λmax value in the chloroform solvent. Thus, it can be confidently concluded that all designed molecules are excellent chromophores.

Efficient charge transfer from the ground state to the excited state requires a low excitation energy value (Ex). It is significant to calculate the Ex in both the gaseous and solvent phases to achieve rapid and effective electron excitation, which ultimately leads to an improvement in the efficiency of PSCs56. Ex values for R and DD1–DD8 in the gaseous medium are as follows: 3.26, 2.24, 2.26, 2.18, 2.51, 2.53, 2.68, 2.85, and 2.59 eV, respectively. The decreasing trend in the gaseous phase is: DD3 > DD1 > DD2 > DD4 > DD5 > DD8 > DD6 > DD7 > R. The Ex values in chloroform medium are as follows: DD3 > DD1 > DD2 > DD5 > DD4 > DD8 > DD6 > DD7 > R, with values ranging from 1.98 to 2.98 eV. The designed molecules (DD1–DD8) have a lower Ex than R, indicating that they require less energy to be excited both in the gas phase and in the chloroform medium. Notably, DD3 has the lowest Ex value in both phases. The lower band-gap value of the proposed chromophores is due to their strong electron-withdrawing acceptors. This reduces their Ex value and facilitates the transition between the two energy states. The proposed chromophores require less Ex than R, which makes them a better option for the development of effective PSCs.

The oscillator strength (fos) is a valuable parameter to evaluate the potential of electronic transitions from HOMO to LUMO after light absorption57. It is computed for different excited states of all molecules. A higher value indicates a more rapid rate of electronic transitions induced by light radiation. The oscillator strengths of the R and DD1–DD8 molecules in gaseous and solvent media are: Gaseous medium: R: 0.91, DD1–DD8: 1.13, 1.15, 1.37, 1.28, 1.17, 1.08, 1.27, Solvent medium: R: 0.92, DD1–DD8: 1.27, 1.28, 1.34, 1.52, 1.49, 1.30, 1.24, 1.43 respectively. The data indicates that the designed molecules (DD1–DD8) possess a significantly higher fos than R in both the gas and solution phases. These results show that the newly developed acceptors are far more efficient. The analysis of Eb revealed that the designed moieties exhibited an improved ability to transfer charge from their donor fragment to the acceptor group. Consequently, all designed molecules (DD1–DD8) exhibited remarkable charge dissociation capacity compared to R. Hence, the designed molecules can be regarded as promising candidates for future OSCs.

The examination of these optical features leads to the conclusion that the newly designed molecules (DD1–DD8) have the potential to significantly enhance the performance of PSCs due to their superior optical parameters. These novel chromophores should be used as the foundation for PSC devices, as improving the optical properties can significantly increase their efficiency.

Light harvesting efficiency and charge mobility

Measuring the light-harvesting efficiency (LHE) of the investigated compounds is crucial for the evaluation of their optical efficacy58. The LHE is determined by the oscillatory strength (f) value of the corresponding wavelength59, which accurately reflects the photocurrent response of the compound60.

The photoreactivity of a compound is directly related to its LHE value, with compounds with a higher LHE value showing a more significant response. It is important to note that for all the designed molecules, absorption occurs in the visible region (463–624 nm) of the solar spectrum as shown in Table 2. Table 3 summarizes the results of applying Eq. (3) to calculate the LHE of the structures in the solvent phase reported in this study. The newly designed structures (DD1–DD8) were prepared with structural modifications that resulted in a significant shift in LHE values. All designed molecules (DD1–DD8) exhibit higher τ and LHE values. This is probably related to their increased photocurrent generation60.

The excited state lifetime (τ) is a critical parameter that directly influences the ability of the material to transfer charge. To increase efficiency, the designed molecules’ lifetime must be longer than the reference molecule. A higher lifetime results in higher charge transfer and lower energy loss61. A higher excited state lifetime is advantageous as it allows charges to recombine and move towards electrodes. Equation (4) calculates the excited state lifetime with precision.

Ex is the excitation energy and f is the oscillator strength of the excited state. As shown in Table 3, the excited lifetime values indicate that DD1 (0.281 ns), DD2 (0.273 ns), DD3 (0.282 ns), DD5 (0.186 ns), and DD6 (0.185 ns) have a significantly higher excited state lifetime than the reference R molecule. Additionally, the lifetime of DD4 is comparable to that of the reference R molecule. The insertion of end groups increases the conjugated length, which improves the excited state lifetime compared to the reference molecule.

Molecular electrostatic potential

Molecular electrostatic potential (MEP) analysis is a powerful tool for identifying electropositive and electronegative sites across a molecule. The MEP map effectively highlights electrophilic and nucleophilic regions and allows for the identification of sites suitable for hydrogen bonding. The diagram displays the electron density of the molecule in 3-D, with distinct colors representing different regions. MEP maps can be used to predict with certainty at which point a molecule either as an electrophile or a nucleophile will attack. The nucleophilic area of the molecule is represented with certainty by the red area, while the blue area represents with certainty the electrophilic area. The crucial gap between these two areas confidently determines the potential for charge distribution. The larger the gap between the red and blue areas, the more confidently we can predict the probability of charge distribution.

Figure 6 shows a distinct gap between the red and blue region, indicating exceptionally good charge separation in all the designed chromophores. The red colour is mainly located at the terminal ends of almost all molecules, indicating negative potential or electronegativity, while the blue colour in the central region indicates positive potential or electro-positivity. The molecules analyzed in this study effectively transfer charge from the central to the terminal part. The acceptor region of the molecule is indicated by the red color, which highlights the presence of nitrogen, fluorine, chlorine, Sulphur, and oxygen atoms. Furthermore, the significant distance between electropositive and electronegative regions in each of the designed molecules guarantees improved stability. DD3 exhibits the highest electronegativity at acceptor regions highlighted in red. MEP analysis verifies that charge distribution occurs within all the molecules, making them ideal for high-performance solar cell devices.

MEP maps of R and DD1–DD8 molecules are made with the help of Gauss View 5.0 (https://gaussview.software.informer.com).

Global reactivity parameters

Global reactivity parameters are used to predict the chemical reactivity of compounds and are calculated using the quantum approach62. These parameters include ionization potential (IP), electron affinity (EA), chemical potential (μ), hardness (η), and softness (s); these properties depend on frontier orbital energies and are shown in Table 463. The concepts of these parameters describe the reactivity, stability, and polarity of atoms and molecules.

The IP of the materials used in the active layer can impact their capacity to facilitate charge transport. Materials with low IP tend to exhibit higher charge mobility, as it is easier to remove an electron and generate a charge carrier. Consequently, these materials can facilitate enhanced functionality of solar devices. The IP of R and designed molecules (DD1–DD8) is; 6.76, 6.96, 6.89, 6.24, 6.68, 6.94, 6.87, 6.73 and 6.70 eV respectively. The value of adiabatic ionization potential varies in ascending order as; DD3 < DD4 < DD8 < DD7 < R < DD6 < DD2 < DD5 < DD1. The data indicates that DD3 has the lowest IP of all the molecules. This indicates that it has better charge transport capabilities, as it is more readily able to donate electrons than R.

Materials with high EA tend to exhibit enhanced charge mobility, as adding an electron and creating a charge carrier becomes more facile. This can result in enhanced functionality of the device. In the case of intramolecular CT, if the EA of the acceptor portion is high, it will exert a stronger pull on the charges, resulting in their movement from the donor to the acceptor region. This movement of charges enhances the charge transport and, ultimately, the performance of OSCs. In the case of electron affinity, the values for R and newly designed molecules (DD1–DD8) are: 0.80, 2.75, 2.65, 2.95, 2.06, 2.33, 2.02, 1.69 and 1.96 eV respectively. This indicates that all designed molecules exhibit a greater capacity to attract charges based on their high electron affinity than R as shown in Fig. 7.

Chemical potential (μ) quantifies the escape potential of an electron and can be linked to electronegativity so that the more negative a chemical potential is, the more difficult it is to lose an electron, but it is easier to gain one. All designed molecules (DD1–DD8) have more negative chemical potential than R, which proves that they can accept electrons, and these parameters are estimated using Eqs. (5–12).

The behaviour of chemical systems can be better understood by considering hardness (η) and softness (S). The hardness of a chemical system reflects its stability, while its softness indicates its reactivity. The energy gap is large for complex molecules, while it is minimal for soft molecules. These two entities are opposite, as illustrated in Fig. 8. Among the designed entities, DD3 has the most remarkable values for softness and hardness, indicating that it is the most reactive of all the designed molecules. The concept of electrophilicity (ω) indicates the ability of a molecule to attract electrons and act as an electrophile, whereas a lower value indicates the ability to donate electrons and act as a nucleophile. Since the designed molecules (DD1–DD8) are acceptors by nature, they all exhibit greater electrophilicity than R, which is noteworthy.

Density of states

Density of states (DOS) analysis is a conclusive test to verify the results of FMOs by determining the increase in energy levels (HOMO and LUMO) per unit of increase. A high DOS value is indicative of the presence of more than one energy level64,65. PSCs typically exhibit more energetic disorder than their inorganic counterparts. This leads to an expansion of the electronic density of states, which in turn pushes the tail states towards the band gap. Consequently, charge carriers tend to accumulate in the tail states, resulting in reduced exciton splitting (electron–hole) and significant Voc loss66. This evaluation is based on a preselected functional and basis set. All molecules have an A1-D-A2 molecular configuration, represented by three lines of varying colors indicating the donor, acceptor, and total contribution. The energies of HOMO and LUMO states are displayed in the DOS graphs, with the abscissa represented by negative integers. The contribution of each fragment (A, D) to the total HOMO and LUMO energy levels is summarized in Table 5.

It can be observed that the central donor majorly contributes HOMO while the acceptor contributes to the formation of LUMO. The designed molecules (DD1–DD8) have donor regions that contribute to the HOMO and acceptor regions that contribute to the formation of the LUMO, as illustrated in Fig. 9. Electron-withdrawing groups at the ends of the designed molecules efficiently enhance the support of their acceptor part in the formation of the LUMO region. These findings are consistent with the FMO study, which demonstrates that all these designed molecules can transfer charges from the donor (HOMO) to acceptor (LUMO) regions, making them highly suitable for creating superior PSCs. The above discussion leads to the conclusion that the end-group modification of the R molecule significantly enhances its electron withdrawal ability. Therefore, the newly designed molecules are strong contenders for high-performance organic solar cells. DD3, DD1, DD2, and DD4 showed a significantly higher percentage contribution of the acceptor part in creating LUMO, with values 78.5%, 78.4%, 77.7% and 71.8% respectively. In contrast, R only had a contribution of 40.5% of the acceptor part.

Representation of density of states for R, DD1–DD8 molecules made by using PyMOlyze 1.1 version (https://sourceforge.net/projects/pymolyze/). All output files of studied compounds were made using Gaussian 09 Version D.01 (https://gaussian.com/g09citation).

The DOS plots show orbital energy in electron volts on the x-axis, while the left y-axis shows relative intensity. The energy levels of HOMO and LUMO orbitals are displayed on the left and right peaks respectively, while the bandgap between them is indicated by the central planar region67. The participation of different fragments is represented by separate-colored lines. The purple line represents the collective electronic density of each fragment, while the blue line represents the individual contribution of the donor. The red line represents the involvement of the acceptor, and the green line represents the involvement of the acceptor along the spacer. The graph of Fig. 9 demonstrates that the peaks of each molecule vary considerably due to the different acceptor groups present on each molecule. These groups have different potential to attract electrons.

Transition density matrix

Transition density matrix (TDM) analysis was executed using the Multiwfn 3.7 application with a 6-31G (d,p) basis set in conjunction with functional (MPW1PW91), which yielded accurate results. The TDM maps show the electronic charge density in different color shades from red to blue, with bright regions indicating a pronounced charge movement from donor to acceptor subunits. The electronic charge density increases from downward to upward on the right side of the vertical axis. Hydrogen atoms are excluded from the TDM plots as they are only slightly involved in the excitation process. The TDM map analysis displays bright fringes indicating the proportion of fermions and transition states that control the excitation phenomenon with precision68.

The TDM plots depict lower charge density using a red color and higher charge density using a blue color. Intermediate electronic density is shown by the pink, white, and sky blue shades69. Figure 10 visually represents the TDM study of reference (R) and designed molecules (DD1–DD8). The efficient diagonal and off-diagonal transport of charge reveals strong electron coupling, leading to fast electron dissociation, which is essential for efficient PSCs. The TDM analysis unequivocally demonstrates the presence of dark spikes, which is a clear indication of charge localization. The substituted acceptor subunits of the DD1–DD8 molecules exhibit remarkably low dark spikes, which is convincing evidence for the efficient transfer of excited electrons from HOMO to LUMO. It is noteworthy that all reported molecules exhibit better charge dissociation ability compared to the reference molecule.

TDM plots of reference (R) and designed molecules (DD1–DD8). The pictures were drawn with Multiwfn 3.7 software (http://sobereva.com/multiwfn/). All output files of studied compounds were made using Gaussian 09 Version D.01 (https://gaussian.com/g09citation).

Reorganization energy

The efficiency of PSCs is significantly impacted by the reorganization energy (RE) as it affects the mobility of charge carriers in the molecules69. The mobility of electrons and holes is inversely related to the RE of a molecule. Therefore, a molecule with a lower RE value can achieve higher electron (λe) and hole (λh) mobility70. Reorganization energy is a critical parameter in determining the energy barrier for charge transport, the charge transfer rate depends on additional factors, including electronic coupling, thermal activation energy, and molecular packing. These factors collectively influence the charge transport dynamics and, consequently, the mobility. Both reorganization energy and charge transfer rates are essential to obtain a comprehensive understanding of charge transport phenomena within a given system. Table 6 displays the calculated RE values of all analyzed molecules. These studies unequivocally demonstrate that the RE properties are strongly correlated with the planarity of the molecule under scrutiny.

The tabulated data shows that λe decreases in the following order: R > DD5 > DD4 > DD7 > DD6 > DD1 > DD2 > DD6 = DD3. This indicates that all of the designed molecules are suitable as electron transport materials, as their RE values are lower than that of the reference molecule. The fine morphology and planar structure of these molecules result in better exciton disintegration and electron mobility. DD3 has the lowest RE value (0.0062 eV) for e-; thus, this molecule can be considered an efficient electron transport material in PCSc among all designed molecules. However, the trend observed in electron values is not observed in the case of RE values for holes. DD3 is a significantly better hole-transporting material than the R molecule due to its low hole values. The molecules may act as acceptors due to their lower electron REs in the PCSc cells.

Open circuit voltage

The open circuit voltage (Voc) represents the maximum voltage along the circuit when there is no current flowing. It is a crucial factor in photovoltaic devices71,72,73,74. The value of Voc is influenced by various factors, such as the light source, temperature, light intensity, and charge mobility. Equation (13) was used to calculate the Voc values of the studied molecules.

As this equation shows, the value of Voc is significantly influenced by the energy gap between the HOMO and LUMO of the donor and acceptor materials. In this study, we computationally calculated Voc by comparing the FMOs of PTB7-Th and acceptor molecules (DD1–DD8), as illustrated in Fig. 11. The PTB7-Th molecule has HOMO and LUMO energy levels of − 5.2 eV and − 3.6 eV, respectively75.

Voc of R and designed molecules (DD1–DD8) with reference to PTB7-Th. All output files of studied compounds were made using Gaussian 09 Version D.01 (https://gaussian.com/g09citation).

The data clearly shows that the DD7 molecule has the highest Voc when paired with PTB7-Th. The general molecule-level trend of increasing Voc is DD3 < DD1 < DD2 < DD5 < DD4 < DD6 DD8 < DD7 < R. This trend is due to the increase in energy gap between the HOMO and LUMO from donor and acceptor materials, which leads to an increase in the Voc of PSCs. Therefore, it can be concluded that DD7 is the most effective molecule in terms of Voc when compared to the other molecules tested. The Voc values of the designed molecules are comparable to that of the reference molecule, based on the aforementioned trend.

Charge transfer analysis between PTB7-Th and DD3

The study presents calculations of the molecular charge transfer behaviour of our recently developed compounds with the involvement of the donor polymer (PTB7-Th). The most efficient new acceptor, DD3, was identified to function alongside the commonly used donor polymer (PTB7-Th). The donor–acceptor materials (PTB7-Th: DD3) were optimized individually and in combination using B3LYP/6-31G(d,p). For the charge transfer analysis with PTB7-Th polymer as the donor, DD3, chosen for its superior electron mobility efficiency and charge transfer properties, was utilized. Due to its lower reorganizational electron mobility values in comparison to other developed molecules (DD1–DD8), it is suggested that PTB7-Th and DD3 are aligned in parallel orientation to achieve optimal structural optimization, as demonstrated in Fig. 12.

Pictorial illustration of CT analysis in PTB7-Th donor and DD3 designed molecule. The picture was made with the help of Gauss View 5.0 (https://gaussview.software.informer.com) and Gaussian 09 version D.01 (https://gaussian.com/g09citation).

Figure 10 illustrates the optimized complex utilizing the MPW1PW91/6-31G (d,p) basis set. The intricate PTB7-Th: DD3 system has achieved perfect alignment whereby the acceptor DD3 is parallel to the donor PTB7-Th. This configuration facilitates the creation of donor–acceptor pairs, which can optimize the flow of charge transfer at the interface.

Conclusion

In this work, eight novel PSCs molecules with different acceptor units are presented. The newly proposed molecules demonstrated significant improvement in results, making the research more applicable. Each of the newly designed molecules showed an improvement in the maximum absorbance in both the gas and solution phases, compared to the reference molecule (PP2). Additionally, all the proposed compounds exhibited low excitation energy and smaller band gap values than R which is very impressive for applications using PSCs. Excellent optoelectronic properties were observed for DD3, which has the smallest band gap of 2.62 eV, the minimum excitation energy Ex of 1.987 eV (solvent phase) and 2.189 eV (gas phase), and λmax value of 566.40 nm (gas phase) and 624.01 nm (solvent phase). All proposed compounds exhibit lower excitation energy and smaller band gap values than R, making them highly suitable for use in PSCs. DD3 has the lowest reorganization energy (λe) among all designed molecules i.e. 0.0062 eV. The creation of a complex with the PTB7-Th donor molecule further confirms charge transfer. These findings strongly suggest that each designed molecule has the potential to surpass the reference molecule (PP2) in PSCs. This theoretical groundwork allows experimentalists to focus their resources on specific materials. Overall, this synergy between theoretical and experimental work fosters innovation in solar cell technology.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Dracup, J. A., Lee, K. S. & Paulson, E. G. Jr. On the definition of droughts. Water Resour. Res. 16, 297–302. https://doi.org/10.1029/WR016i002p00297 (1980).

Bukhary, S., Ahmad, S. & Batista, J. Analyzing land and water requirements for solar deployment in the Southwestern United States. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 82, 3288–3305. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2017.10.016 (2018).

UNFCCC. Paris Agreement—Status of Ratification. Retrieved on 21, 2017 (2016).

Rezk, H. et al. Identifying optimal operating conditions of solar-driven silica gel based adsorption desalination cooling system via modern optimization. Solar Energy 181, 475–489. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solener.2019.02.024 (2019).

Souliotis, M., Arnaoutakis, N., Panaras, G., Kavga, A. & Papaefthimiou, S. Experimental study and life cycle assessment (LCA) of hybrid photovoltaic/thermal (PV/T) solar systems for domestic applications. Renew. Energy 126, 708–723. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2018.04.011 (2018).

Mahmoud, M., Ramadan, M., Olabi, A.-G., Pullen, K. & Naher, S. A review of mechanical energy storage systems combined with wind and solar applications. Energy Convers. Manag. 210, 112670. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2020.112670 (2020).

Wilberforce, T. et al. Overview of ocean power technology. Energy 175, 165–181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2019.03.068 (2019).

Olabi, A. G., Mahmoud, M., Soudan, B., Wilberforce, T. & Ramadan, M. Geothermal based hybrid energy systems, toward eco-friendly energy approaches. Renew. Energy 147, 2003–2012. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2019.09.140 (2020).

Abdelkareem, M. A., Assad, M. E. H., Sayed, E. T. & Soudan, B. Recent progress in the use of renewable energy sources to power water desalination plants. Desalination 435, 97–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.desal.2017.11.018 (2018).

Privado, M. et al. Highly efficient ternary polymer solar cell with two non-fullerene acceptors. Sol. Energy 199, 530–537 (2020).

Wu, H. et al. Impact of donor halogenation on reorganization energies and voltage losses in bulk-heterojunction solar cells. Energy Environ. Sci. 16, 1277–1290 (2023).

Etabti, H., Fitri, A., Benjelloun, A. T., Benzakour, M. & Mcharfi, M. Advancing optoelectronic performance of organic and perovskite photovoltaics: computational modeling of hole transport material based on end-capped dibenzocarbazole molecules. Res. Chem. Intermed. 50, 1895–1927 (2024).

Etabti, H., Fitri, A., Benjelloun, A. T., Benzakour, M. & Mcharfi, M. Designing and theoretical study of dibenzocarbazole derivatives based hole transport materials: application for perovskite solar cells. J. Fluoresc. 33, 1201–1216 (2023).

Chen, B. et al. Effect of fluorine atoms on the dielectric constants, optoelectronic properties and charge carrier kinetic characteristics of indacenodithieno [3, 2-b] thiophene based non-fullerene acceptors for efficient organic solar cells. Sol. Energy 236, 206–214 (2022).

Roncali, J. Luminescent solar collectors: quo vadis?. Adv. Energy Mater. 10, 2001907. https://doi.org/10.1002/aenm.202001907 (2020).

Mateen, F. et al. Large-area luminescent solar concentrator utilizing donor-acceptor luminophore with nearly zero reabsorption: Indoor/outdoor performance evaluation. J. Luminesc. 231, 117837. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jlumin.2020.117837 (2021).

Meinardi, F., Bruni, F. & Brovelli, S. Luminescent solar concentrators for building-integrated photovoltaics. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/natrevmats.2017.72 (2017).

Velarde, A. R. et al. Optimizing the aesthetics of high-performance CuInS2/ZnS quantum dot luminescent solar concentrator windows. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 3, 8159–8163. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsaem.0c01288 (2020).

Yang, C., Liu, D., Renny, A., Kuttipillai, P. S. & Lunt, R. R. Integration of near-infrared harvesting transparent luminescent solar concentrators onto arbitrary surfaces. J. Luminesc. 210, 239–246. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jlumin.2019.02.042 (2019).

Debije, M. G., Evans, R. C. & Griffini, G. Laboratory protocols for measuring and reporting the performance of luminescent solar concentrators. Energy Environ. Sci. 14, 293–301. https://doi.org/10.1039/D0EE02967J (2021).

Coropceanu, I. & Bawendi, M. G. Core/shell quantum dot based luminescent solar concentrators with reduced reabsorption and enhanced efficiency. Nano Lett. 14, 4097–4101. https://doi.org/10.1021/nl501627e (2014).

Huang, H. Y. et al. Eco-friendly, high-loading luminescent solar concentrators with concurrently enhanced optical density and quantum yields while without sacrificing edge-emission efficiency. Sol. RRL 3, 1800347. https://doi.org/10.1002/solr.201800347 (2019).

Griffini, G., Brambilla, L., Levi, M., Del Zoppo, M. & Turri, S. Photo-degradation of a perylene-based organic luminescent solar concentrator: Molecular aspects and device implications. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 111, 41–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solmat.2012.12.021 (2013).

Griffini, G., Levi, M. & Turri, S. Novel crosslinked host matrices based on fluorinated polymers for long-term durability in thin-film luminescent solar concentrators. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 118, 36–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solmat.2013.05.041 (2013).

Griffini, G., Levi, M. & Turri, S. Novel high-durability luminescent solar concentrators based on fluoropolymer coatings. Prog. Organ. Coat. 77, 528–536. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.porgcoat.2013.11.016 (2014).

Banal, J. L., Ghiggino, K. P. & Wong, W. W. Efficient light harvesting of a luminescent solar concentrator using excitation energy transfer from an aggregation-induced emitter. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 16, 25358–25363. https://doi.org/10.1039/C4CP03807J (2014).

Zhao, Y., Meek, G. A., Levine, B. G. & Lunt, R. R. Near-infrared harvesting transparent luminescent solar concentrators. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2, 606–611. https://doi.org/10.1002/adom.201400103 (2014).

Benjamin, W. E. et al. Sterically engineered perylene dyes for high efficiency oriented fluorophore luminescent solar concentrators. Chem. Mater. 26, 1291–1293. https://doi.org/10.1021/cm403286v (2014).

Liu, X., Benetti, D. & Rosei, F. Semi-transparent luminescent solar concentrators based on plasmon-enhanced carbon dots. J. Mater. Chem. A 9, 23345–23352. https://doi.org/10.1039/D1TA02295D (2021).

Gong, X., Zheng, S., Zhao, X. & Vomiero, A. Engineering high-emissive silicon-doped carbon nanodots towards efficient large-area luminescent solar concentrators. Nano Energy 101, 107617. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nanoen.2022.107617 (2022).

Wang, T. et al. Luminescent solar concentrator employing rare earth complex with zero self-absorption loss. Sol. Energy 85, 2571–2579. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solener.2011.07.014 (2011).

Sadeghi, S. et al. Ecofriendly and efficient luminescent solar concentrators based on fluorescent proteins. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 11, 8710–8716. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.9b00147 (2019).

Mateen, F., Oh, H., Jung, W., Binns, M. & Hong, S.-K. Metal nanoparticles based stack structured plasmonic luminescent solar concentrator. Sol. Energy 155, 934–941. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solener.2017.07.037 (2017).

Banaei, E.-H. & Abouraddy, A. F. in High and Low Concentrator Systems for Solar Electric Applications VIII 9–23 (SPIE).

Cao, M., Zhao, X. & Gong, X. Achieving high-efficiency large-area luminescent solar concentrators. JACS Au 3, 25–35. https://doi.org/10.1021/jacsau.2c00504 (2023).

Hwang, D.-Y. et al. Modulation of intramolecular charge transfer in DA functionalized pyrrolopyrazine and their application in luminescent solar concentrators. Dyes Pigm. 221, 111775. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dyepig.2023.111775 (2024).

Wu, H. et al. Effects of Monofluorinated positions at the end-capping groups on the performances of twisted non-fullerene acceptor-based polymer solar cells. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 12, 789–797. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.9b18301 (2019).

Patil, H. et al. Conjoint use of dibenzosilole and indan-1, 3-dione functionalities to prepare an efficient non-fullerene acceptor for solution-processable bulk-heterojunction solar cells. Asian J. Organ. Chem. 4, 1096–1102. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajoc.201500207 (2015).

Wang, L.-L. et al. Insights into the charge-transfer mechanism and stacking structures in a large sample of donor/acceptor models of a non-fullerene organic solar cell. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 11, 9172–9182. https://doi.org/10.1021/acssuschemeng.3c02051 (2023).

Zhu, J. et al. A-D-A type nonfullerene acceptors synthesized by core segmentation and isomerization for realizing organic solar cells with low nonradiative energy loss. Small 20, 2305529. https://doi.org/10.1002/smll.202305529 (2024).

Privado, M. et al. Efficient polymer solar cells with high open-circuit voltage containing diketopyrrolopyrrole-based non-fullerene acceptor core end-capped with rhodanine units. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 9, 11739–11748. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.6b15717 (2017).

Tan, C.-H. et al. Barbiturate end-capped non-fullerene acceptors for organic solar cells: tuning acceptor energetics to suppress geminate recombination losses. Chem. Commun. 54, 2966–2969. https://doi.org/10.1039/C7CC09123K (2018).

Guo, Q. et al. Modulating the middle and end-capped units of A2–A1-D-A1-A2 type non-fullerene acceptors for high VOC organic solar cells. Organ. Electron. 95, 106195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orgel.2021.106195 (2021).

Yao, H., Wang, J., Xu, Y. & Hou, J. Terminal groups of nonfullerene acceptors: design and application. Chem. Mater. 35, 807–821. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemmater.2c03521 (2023).

Frisch, M. Gaussian 16. Revision B 1 (2016).

Finley, J. P. Using the local density approximation and the LYP, BLYP and B3LYP functionals within reference-state one-particle density-matrix theory. Mol. Phys. 102, 627–639 (2004).

Yanai, T., Tew, D. P. & Handy, N. C. A new hybrid exchange–correlation functional using the Coulomb-attenuating method (CAM-B3LYP). Chem. Phys. Lett. 393, 51–57 (2004).

Adamo, C. & Barone, V. Exchange functionals with improved long-range behavior and adiabatic connection methods without adjustable parameters: The m PW and m PW1PW models. J. Chem. Phys. 108, 664–675 (1998).

Ejuh, G., Tchangnwa Nya, F., Ottou Abe, M., Jean-Baptiste, F. & Ndjaka, J. Electronic structure, physico-chemical, linear and non linear optical properties analysis of coronene, 6B-, 6N-, 3B3N-substituted C24H12 using RHF, B3LYP and wB97XD methods. Opt. Quantum Electron. 49, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11082-017-1221-2 (2017).

Zhao, Y. & Truhlar, D. G. The M06 suite of density functionals for main group thermochemistry, thermochemical kinetics, noncovalent interactions, excited states, and transition elements: two new functionals and systematic testing of four M06-class functionals and 12 other functionals. Theor. Chem. Acc. 120, 215–241 (2008).

Wang, Y. et al. M06-SX screened-exchange density functional for chemistry and solid-state physics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 117, 2294–2301. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.191369911 (2020).

Dennington, R., Keith, T. & Millam, J. GaussView 5.0 (Gaussian Inc., 2008).

Barone, V. & Cossi, M. Quantum calculation of molecular energies and energy gradients in solution by a conductor solvent model. J. Phys. Chem. A 102, 1995–2001 (1998).

Tenderholt, A. L. et al. Electronic control of the “bailar twist” in formally d0–d2 molybdenum tris (dithiolene) complexes: A sulfur K-edge X-ray absorption spectroscopy and density functional theory study. Inorg. Chem. 47, 6382–6392 (2008).

Lu, T. & Chen, F. Multiwfn: A multifunctional wavefunction analyzer. J. Comput. Chem. 33, 580–592 (2012).

Wei, Y. et al. The charge-transfer states and excitation energy transfers of halogen-free organic molecules from first-principles many-body Green’s function theory. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 286, 121925. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.saa.2022.121925 (2023).

Yang, C., Liu, T., Song, P., Ma, F. & Li, Y. Revealing the photoelectric performance and multistep electron transfer mechanism in DA-π-A dyes coupled with a chlorophyll derivative for co-sensitized solar cells. J. Mol. Liq. 368, 120797. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molliq.2022.120797 (2022).

Peumans, P., Yakimov, A. & Forrest, S. R. Small molecular weight organic thin-film photodetectors and solar cells. J. Appl. Phys. 93, 3693–3723 (2003).

Bhattacharya, L., Sharma, S. & Sahu, S. Enhancement of air stability and photovoltaic performance in organic solar cells by structural modulation of bis-amide-based donor-acceptor copolymers: a computational insight. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 121, e26524 (2021).

Ghahramanpour, M., Jamehbozorgi, S. & Rezvani, M. The effect of encapsulation of lithium atom on supramolecular triad complexes performance in solar cell by using theoretical approach. Adsorption 26, 471–489. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10450-019-00196-1 (2020).

Nalçakan, H., Kurtay, G., Sarıkavak, K., Şen, N. & Sevin, F. Computational insights into bis-N, N-dimethylaniline based D-π-A photosensitizers bearing divergent-type of π-linkers for DSSCs. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 122, 108485. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmgm.2023.108485 (2023).

Qundeel, et al. Impact of end-capped engineering on the optoelectronic characteristics of pyrene-based non-fullerene acceptors for organic photovoltaics. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 124, e27344 (2024).

Iqbal, M. M. A., Hassan, T., Hussain, R. & Hussain, M. A quest to explore electron-accepting behaviour of intramolecular nitrogen-sulfur interaction with terminal groups for potential applications in organic solar cells: A theoretical insight. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 188, 109200 (2025).

Paramasivam, M., Chitumalla, R. K., Jang, J. & Youk, J. H. The impact of heteroatom substitution on cross-conjugation and its effect on the photovoltaic performance of DSSCs—a computational investigation of linear vs. cross-conjugated anchoring units. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 20, 22660–22673, https://doi.org/10.1039/C8CP02709A (2018).

Bilal Ahmed Siddique, M. et al. Designing triphenylamine‐configured donor materials with promising photovoltaic properties for highly efficient organic solar cells. ChemistrySelect 5, 7358–7369. https://doi.org/10.1002/slct.202001989 (2020).

Liu, S. et al. High-efficiency organic solar cells with low non-radiative recombination loss and low energetic disorder. Nat. Photon. 14, 300–305 (2020).

Mubashar, U. et al. Designing and theoretical study of fluorinated small molecule donor materials for organic solar cells. J. Mol. Model. 27, 216. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00894-021-04831-z (2021).

Atiq, K., Iqbal, M. M. A., Hassan, T. & Hussain, R. An efficient end-capped engineering of pyrrole-based acceptor molecules for high-performance organic solar cells. J. Mol. Model. 30, 13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00894-023-05799-8 (2024).

Iqbal, M. M. A., Hassan, T. & Hussain, R. Tailoring of centric extent fullerene-free acceptors to improve photoelectric properties of organic solar cells: A computational approach. Comput. Theor. Chem. 1235, 114542. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comptc.2024.114542 (2024).

Iqbal, M. M. A., Arshad, M., Mehboob, M. Y., Khan, M. S. & Piracha, S. Designing efficient AD-A1-DA type fullerene free acceptor molecules with enhanced power conversion efficiency for solar cell applications. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 285, 121844. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.saa.2022.121844 (2023).

Waqas, M. et al. Designing of symmetrical ADA type non-fullerene acceptors by side-chain engineering of an indacenodithienothiophene (IDTT) core based molecule: a computational approach. Comput. Theor. Chem. 1217, 113904. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comptc.2022.113904 (2022).

Shukla, R., Punetha, D., Kumar, R. R. & Pandey, S. K. Examining the performance parameters of stable environment friendly perovskite solar cell. Opt. Mater. 143, 114124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.optmat.2023.114124 (2023).

Subudhi, P. & Punetha, D. Progress, challenges, and perspectives on polymer substrates for emerging flexible solar cells: A holistic panoramic review. Prog. Photovolt. Res. Appl. 31, 753–789. https://doi.org/10.1002/pip.3703 (2023).

Subudhi, P. & Punetha, D. Pivotal avenue for hybrid electron transport layer-based perovskite solar cells with improved efficiency. Sci. Rep. 13, 19485. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-33419-1 (2023).

Shehzad, R. A. et al. Designing of benzothiazole based non-fullerene acceptor (NFA) molecules for highly efficient organic solar cells. Comput. Theor. Chem. 1181, 112833 (2020).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge University of Okara for providing technical support for this project. We are also grateful to COMSAT University Islamabad, Abbottabad, Pakistan for supporting computing facilities.

Funding

Authors received no funding for the study, authorship or publishing of this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Malik Muhammad Asif Iqbal: Conceptualization, Project administration, Data curation, Resources, Supervision, Software, paper editing. Muzamil Hussain: Visualization, Validation, Methodology. Riaz Hussain: Data Analysis, Data curation, Visualization. Supervision. Waqar Ashraf: Visualization, Validation, Methodology.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Iqbal, M.M.A., Hussain, M., Hussain, R. et al. Designing of pyrrolopyrazine-based electron transporting materials with architecture (A1-D-A2) in perovskite solar cells: a DFT study. Sci Rep 15, 15403 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87375-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87375-z