Abstract

Preservation of residual kidney function (RKF) is important in patients undergoing peritoneal dialysis (PD). We aimed to examine the association between anemia management and residual urine output using data from a nationwide survey of dialysis patients. After excluding patients with anuria at baseline from the Total cohort of 2,712, 659 of 1,640 patients developed anuria during a median follow-up of 2.5 (interquartile range: 1.5–4.2) years. Urine volume decreased more rapidly as hemoglobin decreased or as the erythropoiesis-stimulating agent (ESA) resistance index (ERI) increased. The hazard ratios with 95% confidence intervals for the development of anuria, defined as residual urine volume ≤ 100 mL/day, were 1.65 (1.20–2.27), 1.39 (1.08–1.77), and 1.32 (1.07–1.63) for hemoglobin levels of < 9.0, 9.0–9.9, and 10.0–10.9 g/dL compared with 11.0–11.9 g/dL, and 1.35 (1.10–1.66) and 1.41 (1.14–1.73) for the second and third tertiles of ERI compared with the first tertile. In conclusion, patients with a low hemoglobin level or a high ERI were more likely to experience a decline in residual urine output and to develop anuria. Further studies are needed to investigate the effects of interventions that could improve renal anemia and/or ESA hyporesponsiveness on RKF preservation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Residual kidney function (RKF) declines progressively with the loss of functional kidney parenchyma and is associated with survival1,2. The benefits of preserving RKF have been highlighted especially in patients undergoing peritoneal dialysis (PD); not only is preserving RKF beneficial independent of the total dose of small solute clearance delivered3, but it is also considered more important than peritoneal clearance4. Preservation of RKF provides multifaceted benefits, including reduced blood pressure and left ventricular hypertrophy, improved fluid status, lower serum β2-microglobulin levels, higher hemoglobin levels, and better nutritional status5,6,7. Residual urine output is a simple measure used as a surrogate for RKF in routine clinical practice8. Anuria is often defined as a residual urine volume of ≤ 100 mL/day.9,10 Patients with preserved residual urine volume generally have a better prognosis11.

Our previous study demonstrated a U-shaped association between hemoglobin levels and mortality in patients undergoing PD12, underscoring the importance of effective anemia management for survival. However, to the best of our knowledge, the impact of anemia management on RKF preservation has not been thoroughly explored.

In patients with kidney failure, decreased production of endogenous erythropoietin leads to renal anemia, often requiring the administration of erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (ESAs). Some patients develop ESA hyporesponsiveness, necessitating increased ESA doses to maintain hemoglobin levels13,14. ESA hyporesponsiveness, which is often expressed as ESA resistance index (ERI), has been associated with adverse clinical outcomes, including increased risk of mortality and cardiovascular events in patients on dialysis15,16.

While the mechanisms underlying ESA hyporesponsiveness are complex, RKF is considered to be relevant. For example, the required dose of ESAs was lower in patients undergoing PD compared to patients on hemodialysis (HD)17,18. In addition, patients with preserved RKF exhibited a better response to ESAs19. Despite these observations, there has been little quantitative evaluation of how residual urine volume relates to ESA hyporesponsiveness in patients undergoing PD.

Therefore, this study aimed to investigate how hemoglobin levels and ESA resistance were associated with longitudinal changes in residual urine output. In an exploratory analysis, we also aimed to identify factors associated with ESA resistance and to quantify the association between residual urine output and ESA resistance. We used data on patients undergoing PD from a nationwide dialysis survey.

Results

Patient selection and cohort setting

This was a cohort study using data collected from patients undergoing PD in the Japanese Society for Dialysis Therapy (JSDT) Renal Data Registry (JRDR) database. A flowchart of the patient inclusion process is presented in Fig. 1. Among patients undergoing PD and registered in the database in 2012 (n = 9,570), those who aged ≥ 18 years, survived and underwent PD by the end of 2012 were enrolled and followed up until the end of 2021 (n = 8,819). We excluded patients undergoing combination therapy with HD at the end of 2012 (n = 1,662), patients whose hemoglobin level data were not available (n = 2,282), and patients whose urine volume and ESA dose data were not available (n = 1,618 and 545, respectively) (the remaining patients were labeled the Total cohort, n = 2,712). After excluding patients with anuria, we investigated the association between baseline ESA resistance and subsequent urine output trajectories in the remaining patients (this group was defined as the Analytic cohort, n = 1,640).

Flow diagram of patient selection. In the Total cohort, patients undergoing PD with available data on ESA dose and residual urine were included to examine the association between urine output and ERI. In the Analytic cohort, after excluding those with a urine volume ≤ 100 mL/day at baseline and those with only one urine data available, we examined the longitudinal association of ERI with urine output. PD, peritoneal dialysis; ESA, erythropoiesis-stimulating agent; ERI, ESA resistance index; UV, urine volume.

Baseline characteristics

The baseline characteristics of the Analytic cohort and number of missing values are shown in Table 1. The mean age of the participants was 62 years, and 63% were men. The median time since starting dialysis was 21 months, and the mean (standard deviation) hemoglobin level was 10.9 (1.3) g/dL. The median total, PD, and residual kidney Kt/V values were 2.0, 1.3, and 0.70, respectively, with substantial proportion of missing values. Approximately 25% of the participants had diabetic nephropathy. The mean TSAT was 35.2%, and the median ferritin level was 113 ng/mL.

The baseline characteristics of participants in the Total cohort according to residual urine volume categories are presented in Supplementary Table 1. Residual urine volume was divided into three categories: ≤100, > 100–500, and > 500 mL/day. Of the 2,712 patients, 438 (16%) had anuria, and 2,450 (90%) used ESAs. Participants with a residual urine volume of > 500 mL/day were more likely to have been undergoing dialysis for a shorter time period, have a higher residual kidney Kt/V, lower ESA dose, and lower ERI. TSAT and ferritin levels were similar across the urine volume categories.

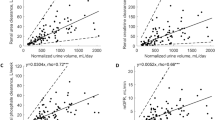

Association of hemoglobin levels and ERI with longitudinal urine volume trajectory and anuria

In the Analytic cohort, the number of records of urine volume gradually decreased over time (Supplementary Fig. 1). We therefore estimated the longitudinal trajectory using up to 6 years of data. The longitudinal trajectories of residual urine volume varied significantly across hemoglobin levels (Fig. 2A, P for interaction < 0.001) and ERI tertiles (Fig. 2B, P for interaction < 0.001). The estimated differences in time to anuria, defined as urine volume ≤ 100mL/day, were approximately 2 years between a hemoglobin level of < 9.0 g/dL and the reference category of 11.0–11.9 g/dL and 1 year between the first and third ERI tertiles. These differences were estimated from the graph showing the urine volume trajectory. This means that the higher the hemoglobin or the lower the ERI, the longer the estimated time to anuria.

Longitudinal trajectories of residual urine output across levels of hemoglobin and ESA resistance index at baseline. Longitudinal trajectories of residual urine output across levels of hemoglobin (A) and ERI tertiles (B) were estimated using mixed-effects models. The residual urine output decreased more rapidly over time in patients with lower hemoglobin levels or higher ERI. Models were adjusted for age, sex, time since dialysis initiation, and log-transformed urine volume at baseline. ESA, erythropoiesis-stimulating agent; ERI, ESA resistance index.

Here we used the following two definitions of anuria: type A and B (Supplementary Fig. 2A and 2B). The cumulative incidence of anuria using the two definitions is shown in Supplementary Fig. 3A and 3B for type A and B, respectively. Type A anuria events occurred in 659 patients (median follow-up period, 2.5 [IQR, 1.5–4.2] years), while type B anuria events occurred in 572 patients (median follow-up period, 2.0 [IQR, 1.0–3.4] years). We used type A anuria events as in the primary analysis.

We examined the association between hemoglobin levels and anuria using multivariable Cox regression analysis (Fig. 3). Patients with hemoglobin levels < 11 g/dL were more likely to develop anuria than the reference level of 11.0–11.9 g/dL, with HRs and 95% CIs of 1.65 (1.20–2.27), 1.39 (1.08–1.77), and 1.32 (1.07–1.63) for those with hemoglobin levels < 9.0, 9.0–9.9, and 10.0–10.9 g/dL, respectively, in Model 5. The association was attenuated when nutritional parameters, specifically, serum albumin were added. Sensitivity analyses showed consistent results (Supplementary Table 2).

Association between hemoglobin levels and anuria. Covariates in multivariable adjustment models were as follows: age, sex, time since starting PD, hypertension, urine output at baseline, weekly ESA dose; DM, BMI, history of myocardial infarction, history of stroke, total Kt/V, and smoking (Model 1, a demographic model); Model 1 + TSAT, and ferritin (Model 2, + iron indices); Model 2 + phosphorus, calcium, and intact PTH (Model 3, + CKD-MBD markers); Model 3 + CRP and history of peritonitis (Model 4, + inflammation); Model 4 + albumin and total cholesterol (Model 5, nutritional indices). HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; ESA, erythropoiesis-stimulating agent; ERI, ESA resistance index; PD, peritoneal dialysis; DM, diabetes mellitus; BMI, body mass index; TSAT, transferrin saturation; PTH, parathyroid hormone; CKD-MBD, chronic kidney disease mineral and bone disorder; CRP, C-reactive protein.

We also showed that the second and third ERI tertiles were significantly associated with the occurrence of anuria, with HRs and 95% CIs of 1.35 (1.10–1.66) and 1.41 (1.14–1.73) for the second and third tertiles of ERI, respectively (Table 2). The HR of ERI for anuria occurrence was attenuated by the addition of CKD-mineral and bone disorder (MBD) markers (from Model 2 to Model 3) and nutritional parameters (from Model 4 to Model 5). Sensitivity analyses showed consistent results (Supplementary Table 3). In the RCS analysis, the occurrence of anuria was associated with increased ERI (Fig. 4).

Non-linear association between ESA resistance index and risk of anuria. Non-linear estimation of residual urine output was demonstrated using restricted cubic spline analysis with three knots at the 10th, 50th, and 90th percentiles of ERI in all patients (A) and in those who were administered ESA (B). The reference category was placed on the median values of ERI, 2.47 (A) and 2.68 (B). A multivariable regression model was adjusted for the variables in Model 5. ESA, erythropoiesis-stimulating agent; ERI, ESA resistance index.

Association between residual urine volume and ERI (exploratory analysis)

Cross-sectional analysis using the Total cohort (n = 2,712) revealed that as the residual urine volume decreased, the estimated ERI increased in the multivariable-adjusted models. The point estimates decreased after including nutritional markers such as serum albumin and total cholesterol levels (Supplementary Table 4). Similar results were obtained when serum albumin level alone was added to Model 4. Factors associated with elevated ERI were older age, female sex, time since starting dialysis, hypertension, elevated phosphorus and CRP levels, and decreased serum albumin and total cholesterol levels (Supplementary Table 5). A non-linear association was observed in the RCS (Supplementary Fig. 4). The estimated ERI tended to be lower with higher residual urine volume in an almost linear fashion when the urine volume was > 100 mL/day. In contrast, when the urine volume was ≤ 100 mL/day, the estimated ERI remained consistently high. Similar results were obtained when different ERI definitions were used (Supplementary Tables 6 and Supplementary Fig. 5).

Overall survival and comparison of survival outcomes (exploratory analysis)

Using the Total cohort (n = 2,712), we also examine the association of ERI or residual urine volume with all-cause mortality. During a median follow-up period of 3.5 (interquartile range [IQR], 1.5–6.3) years, 759 patients died, 101 patients underwent kidney transplantation, and 1,483 patients were transferred to HD. The Kaplan–Meier curve exhibited a difference in mortality based on residual urine output (P < 0.001) (Supplementary Fig. 6A), whereas no difference was observed in mortality based on the ERI tertiles (Supplementary Fig. 6B and 6 C). In the multivariable Cox models, compared to the reference urine output category of > 500 mL/day, anuria (urine volume ≤ 100 mL/day) was significantly associated with risk of mortality with the adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) of 1.59 (1.26–2.01), while elevated ERI was not associated with increased risk of mortality (Supplementary Table 7).

Discussion

Using data on patients undergoing PD from a nationwide dialysis survey, this study revealed two important findings. First, we clearly demonstrated the potential role of anemia management in preserving RKF, which has not been formally addressed in previous studies. Second, exploratory analysis revealed that urine volume ≤ 100 mL/day was associated with ESA hyporesponsiveness and risk of mortality, which were of clinical significance. Interestingly, an inverted J-curve association with residual urine output was observed: the ERI decreased linearly with increasing urine output when urine output was > 100 mL/day, whereas it remained high and almost unchanged with decreasing urine volumes when urine output was ≤ 100 mL/day. This is the first study to quantitatively assess the association between residual urine volume and ESA hyporesponsiveness.

We found that a low hemoglobin level or a high ERI at baseline was associated with a long-term decline in residual urine output, and we demonstrated the robustness of the results through several sensitivity analyses. Interestingly, our study successfully demonstrated that the trajectory of decline in residual urine volume varies with hemoglobin levels in patients undergoing PD and that the duration of preserved residual urine output differed depending on hemoglobin levels (Figs. 2A and 3). Specifically, an approximate 2-year difference in time to anuria was observed between hemoglobin levels < 9.0 g/dL and the reference category of 11.0–11.9 g/dL (Fig. 2A). Furthermore, this association was also observed for ERI: the difference of approximately 1 year was observed between the first and third tertiles of ERI (Fig. 2B). These findings provide clear evidence of the importance of anemia management on preserving RKF.

In this study, both hemoglobin levels and ERI showed an association with preservation of RKF, whereas ERI, unlike hemoglobin levels12, was not significantly associated with mortality (Supplementary Table 7). This may be because inflammation and iron deficiency were less pronounced in Japanese patients on PD. In this study, iron storage parameters were mostly adequate, with a mean TSAT of 35% and a median ferritin of 113 ng/mL. According to the results of a recent PDOPPS study20, while > 80% of Japanese patients undergoing PD had ferritin levels < 300 ng/mL, only 11% of the patients had TSAT levels < 20%, with almost 30% of patients receiving iron administration. Note that the Japanese guidelines for renal anemia recommend maintaining ferritin levels < 300 ng/mL.21 In these iron indices, 83% of patients had hemoglobin levels > 10 g/dL and were well controlled, suggesting that iron was being utilized effectively. The low level of inflammation in the Japanese PD population may also have contributed to this favorable iron utilization. In this study, the median value of CRP was as low as 0.10 mg/dL. Similar results have been reported in Japanese patients on HD22. In addition, a low incidence of PD-related peritonitis has been reported23. Although the association with mortality was not clear, the association of ERI with urine volume trajectory or anuria provides valuable insight into the importance of anemia management for the preservation of RKF.

The association between anemia management and residual urine output was attenuated by several factors in this study. Serum albumin levels attenuated the impacts of hemoglobin levels or ERI on the longitudinal trajectory of residual urine output (Table 2; Fig. 3). As albumin is considered to be an inflammatory marker24, these findings may suggest that inflammation and/or malnutrition may be associated with anemia management and RKF decline. A recent retrospective observational study found that the use of a hypoxia-inducible factor prolyl hydroxylase inhibitor was associated with improvement in anemia as well as preservation of RKF and lower CRP levels25. Further studies are needed to investigate the effectiveness of this medicine on RKF and ERI. The present study also found that the association between ERI and anuria was attenuated by the addition of CKD-MBD markers (Table 2). Previous studies have shown that high PTH levels were associated with decreased RKF in patients undergoing HD26, whereas low phosphorus levels were associated with preserved RKF in patients undergoing PD27. Thus, CKD-MBD, inflammation, and nutrition may be potential targets for preserving RKF and improving anemia management in patients undergoing PD.

Previous studies have shown that patients with preserved RKF had a better response to ESAs19, and preserved residual urine volume has also been associated with lower ESA requirements11. However, in the latter study, the presence or absence of residual urine output was defined by whether one cup of urine (250 mL/day) was maintained on the basis of a questionnaire and was not treated and assessed as a continuous value. In the present study, both residual urine output and ESA resistance were treated and analyzed as continuous values, and their associations were clearly demonstrated. Notably, the association appeared to be quite different between residual urine volumes below and above 100 mL/day. Although a residual urine output of 100 mL/day is widely accepted as the threshold for anuria9,10, there was insufficient evidence to support this value28. This study provides valuable insights into the clinical significance of this value.

This study had several limitations. First, this was an observational study, which limits the interpretation of causal relationships. The association between residual urine output and ERI was based on a cross-sectional analysis. However, the findings provided new clinical significance to the value of 100 mL/day of residual urine volume. Second, we employed variables with definitions that are not well established, such as ERI, which was not based on body weight, and anuria, which was imputed with a mixed-effects model. We conducted several sensitivity analyses to address this uncertainty and obtained consistent results (Supplementary Tables 2, 3, 6, and 7). Third, our data did not include details of medications or PD-related factors. For example, the use of iron supplementations or types of antihypertensive agents, such as renin–angiotensin system inhibitors, were not available. Nevertheless, the patients in this study had well-controlled iron stores. The use of renin–angiotensin system inhibitors and biocompatible PD solutions can preserve RKF29, whereas nephrotoxic agents may disrupt it7. However, neutral-pH solutions with low-glucose degradation products allow excellent preservation of RKF and larger urine volumes30,31, and such biocompatible PD solutions are widely used in Japan32. Fourth, the present study did not provide a clear cut-off for ERI with regard to its association with outcomes. However, a novelty is that it showed an association of ERI with anuria or reduced urine output. Future research is needed to determine ESA hyporesponsiveness based on ERI values. Fifth, there is the potential for immortal-time bias. Patients with multiple urine volume records may remain in the cohort, ensuring the survival of these patients. However, this is unavoidable due to the study design. Without collecting information on urine output at multiple time points, it is not possible to observe the outcome of urine output or anuria. Finally, our results were derived from a single country, which may limit their generalizability. Namely, external validation is needed in populations where larger PD solution volumes are required to provide adequate dialysis.

In conclusion, this study demonstrated that patients with high hemoglobin levels or low ERI were more likely to have a preserved residual urine output and were less likely to develop anuria. We also identified the clinical significance of a residual urine volume of 100 mL/day. Further studies are needed to investigate the effects of interventions that could improve renal anemia and/or ESA hyporesponsiveness on the preservation of RKF.

Materials and methods

Study design and population

JRDR is a nationwide dialysis registry that conducts a survey at the end of each year to collect dialysis-related parameters and event data. Details of the JRDR are described elsewhere21. Data acquisition in the JRDR is planned a priori, and the target patients and data items are clearly defined in advance. Data collection is continuously conducted according to predefined rules. In Japan, biocompatible neutral PD solutions were introduced in the early 2000s, and have gained prevalence since then23,32. The study protocol was approved by the Medicine Ethics Committee of the JSDT, and the study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent to participate in the study was waived by the ethics committee because the data were anonymized and no intervention was performed for research purposes.

Definition of variables

The weekly dose of epoetin was divided by 200, and the monthly dose of epoetin beta pegol was divided by four to convert to a weekly darbepoetin-equivalent dose33,34. If ESA doses recorded in the dataset exceeded the insurance-covered doses owing to inaccurate data entries, they were considered missing values. The ERI was given by the following Eqs13,35:

1) Darbepoetin alpha-equivalent ESA dose divided by hemoglobin level … primary analysis.

2) Epoetin alpha-equivalent ESA dose divided by hemoglobin level and body weight … sensitivity analysis.

We used the latter definition in a sensitivity analysis owing to the substantial missing data for body weight. Whole PTH levels measured by bio-intact assays were multiplied by 1.7 to obtain equivalent intact PTH values36.

Covariates in multivariable models

The covariates in multivariable models collected at baseline were as follows: Age, sex, time since starting dialysis, hypertension, DM, BMI, history of myocardial infarction, history of stroke, total Kt/V, smoking, log-transformed urine volume (except when the exposure was urine output), and weekly ESA dose (except when the exposure was ERI or urine output) (Model 1, a demographic model); Model 1 + transferrin saturation (TSAT), and ferritin (Model 2, including iron indices); Model 2 + phosphorus, calcium, and intact PTH (Model 3, including CKD-MBD markers); Model 3 + C-reactive protein (CRP) and history of peritonitis (Model 4, including inflammation-related variables); Model 4 + albumin and total cholesterol (Model 5, including nutritional indices).

Outcomes

In the Analytic cohort, we defined anuria as residual urine volume ≤ 100 mL/day9,10. The method of estimating time to anuria is described in Supplementary Fig. 2. Since anuria was determined in the annual survey, which was conducted at fixed time intervals, we implemented an ad hoc approach to impute the timing of the occurrence of anuria37. Two types of time intervals during which an event could occur are possible: an interval bracketed by an annual record and a censoring event; and an interval bracketed by two annual records. In the first type of interval, no urine information was available after the study participant’s last annual urine record, but they were still alive and being followed up. We, therefore, estimated urine volume using a mixed-effects model and regressed it linearly to the participant’s censoring event (Supplementary Fig. 2A, type A). When the regression line intersected the threshold of 100 mL/day before the censoring event, that time was recognized as the occurrence of anuria. In the second type of interval, urine volume values are available on both sides of the interval. We assumed log-transformed urine volume changed linearly over time within the interval. If, at the end of the interval, urine volume had fallen to or below 100 mL/day, the timing of the event’s occurrence was estimated by drawing a straight line within the interval (Supplementary Fig. 2B, type B). Follow-up was censored at any of the following events: transition to thrice-weekly HD, withdrawal from dialysis, kidney transplantation, or the end of 2021. In the sensitivity analysis, we also considered the initiation of combination therapy between HD and PD as a censoring event in addition to the above-mentioned censoring events.

In an exploratory analysis using the Total cohort, the outcomes were all-cause death in the longitudinal analysis and the ERI in the cross-sectional analysis.

Statistical analysis

The baseline characteristics of the Total cohort were compared according to the three categories of residual urine volume. Data are presented as numbers (%), means (standard deviation), or medians (interquartile ranges [IQR]), as appropriate.

A mixed-effects model with an unstructured variance-covariance structure was employed to consider patient-level random effects to examine the longitudinal urine volume trajectory across hemoglobin levels and ERI tertiles at baseline. Multivariable analyses were performed after adjusting for age, sex, time since dialysis initiation, and the log-transformed urine volume at baseline. We also examined the association of hemoglobin levels and ERI at baseline with the occurrence of anuria using multivariable Cox regression models. Hemoglobin levels between 11.0 and 11.9 g/dL were considered the reference category.

We imputed the missing values in the multivariable linear regression and Cox regression models using multiple imputations with chained equations38,39. Variables used in multiple imputations included exposure of interest, covariates in the multivariable models, the endpoint indicator, and the Nelson–Aalen cumulative hazard estimate. The results for the 100 imputed data sets were combined using Rubin’s rule.

In an exploratory analysis, we performed a multivariable linear regression analysis to explore factors associated with ERI and to examine the association between ERI and urine output using the Total cohort. Furthermore, all-cause mortality was compared across categories of urine output or ERI tertiles using the Kaplan–Meier method and log-rank tests. The association of urine output or ERI with all-cause mortality was examined using multivariable Cox proportional hazards models. The urine output category of > 500 mL/day was selected as the reference.

Assuming a nonlinear association between exposures and outcomes, we performed restricted cubic spline (RCS) analysis to examine the longitudinal association between ERI and anuria occurrence based on Cox regression, and the cross-sectional association between residual urine volume and ERI. In the Cox model, the reference value was set as the median ERI value. The proportional hazard assumption was graphically assessed using Schoenfeld residuals. In all analyses, a two-sided P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using Stata MP version 18.0 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX, USA).

Data availability

Owing to personal information protection laws, our data are not freely available. The data underlying this article will be shared upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

References

Perl, J. & Bargman, J. M. The importance of residual kidney function for patients on dialysis: a critical review. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 53, 1068–1081 (2009).

Maiorca, R. et al. Predictive value of dialysis adequacy and nutritional indices for mortality and morbidity in CAPD and HD patients. A longitudinal study. Nephrol. Dial Transpl. 10, 2295–2305 (1995).

Szeto, C. C. et al. Importance of dialysis adequacy in mortality and morbidity of Chinese CAPD patients. Kidney Int. 58, 400–407 (2000).

Boudville, N. & de Moraes, T. P. Guidelines on targets for solute and fluid removal in adults being treated with chronic peritoneal dialysis: 2019 update of the literature and revision of recommendations. Perit. Dial Int. 40, 254–260 (2005). (2020).

Marrón, B., Remón, C., Pérez-Fontán, M., Quirós, P. & Ortíz, A. Benefits of preserving residual renal function in peritoneal dialysis. Kidney Int. 73, S42–S51 (2008).

Nongnuch, A., Assanatham, M., Panorchan, K. & Davenport, A. Strategies for preserving residual renal function in peritoneal dialysis patients. Clin. Kidney J. 8, 202–211 (2015).

Curran, S. P. & Bargman, J. M. The importance of residual renal function in peritoneal dialysis. Dial Transpl. 40, 349–355 (2011).

Pinto, J., Debowska, M., Gomez, R., Waniewski, J. & Lindholm, B. Urine volume as an estimator of residual renal clearance and urinary removal of solutes in patients undergoing peritoneal dialysis. Sci. Rep. 12, 18755 (2022).

Peritoneal Dialysis Adequacy 2006 Work Group. Clinical practice guidelines for peritoneal adequacy, update 2006. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 48 (Suppl 1), S91–97 (2006).

Li, P. K. T. et al. ISPD peritonitis guideline recommendations: 2022 update on prevention and treatment. Perit. Dial Int. 42, 110–153 (2022).

Shafi, T. et al. Association of residual urine output with mortality, quality of life, and inflammation in incident hemodialysis patients: the choices for healthy outcomes in caring for end-stage renal disease (CHOICE) study. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 56, 348–358 (2010).

Imaizumi, T. et al. Management of anaemia and prognosis of patients undergoing maintenance peritoneal Dialysis: A nationwide cohort study. Perit. Dial. Int. https://doi.org/10.1177/08968608241244995 (2024).

Weir, M. R. Managing Anemia across the stages of kidney disease in those Hyporesponsive to Erythropoiesis-Stimulating agents. Am. J. Nephrol. 52, 450–466 (2021).

Wu, H. H. L. & Chinnadurai, R. Erythropoietin-stimulating Agent Hyporesponsiveness in patients living with chronic kidney disease. Kidney Dis. (Basel). 8, 103–114 (2022).

Panichi, V. et al. Anaemia and resistance to erythropoiesis-stimulating agents as prognostic factors in haemodialysis patients: results from the RISCAVID study. Nephrol. Dial Transpl. 26, 2641–2648 (2011).

Kuragano, T. et al. ESA hyporesponsiveness is Associated with adverse events in maintenance hemodialysis (MHD) patients, but not with Iron Storage. PLoS One. 11, e0147328 (2016).

Bae, M. N. et al. Association of Erythropoietin-Stimulating Agent responsiveness with mortality in Hemodialysis and Peritoneal Dialysis patients. PLoS One. 10, e0143348 (2015).

Duong, U. et al. Mortality associated with dose response of erythropoiesis-stimulating agents in hemodialysis versus peritoneal dialysis patients. Am. J. Nephrol. 35, 198–208 (2012).

Wang, A. Y. M. et al. Important differentiation of factors that predict outcome in peritoneal dialysis patients with different degrees of residual renal function. Nephrol. Dial Transpl. 20, 396–403 (2005).

Perlman, R. L. et al. International Anemia Prevalence and Management in Peritoneal Dialysis patients. Perit. Dial Int. 39, 539–546 (2019).

Yamamoto, H. et al. 2015 Japanese Society for Dialysis Therapy: guidelines for renal Anemia in chronic kidney disease. Ren. Replace. Therapy. 3, 36 (2017).

Kawaguchi, T. et al. C-Reactive protein and mortality in Hemodialysis patients: the Dialysis outcomes and practice patterns study (DOPPS). Nephron Clin. Pract. 117, c167–c178 (2010).

Perl, J. et al. Peritoneal Dialysis–related infection rates and outcomes: results from the peritoneal Dialysis outcomes and practice patterns study (PDOPPS). Am. J. Kidney Dis. 76, 42–53 (2020).

Friedman, A. N. & Fadem, S. Z. Reassessment of albumin as a nutritional marker in kidney disease. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 21, 223–230 (2010).

Wu, T. et al. Efficacy of Roxadustat on anemia and residual renal function in patients new to peritoneal dialysis. Ren. Fail. 44, 529–540 (2022).

Lee, Y. J. et al. Association of Mineral Bone Disorder with decline in residual kidney function in Incident Hemodialysis patients. J. Bone Min. Res. 35, 317–325 (2020).

Murashima, M. et al. Associations of calcium, phosphate and intact parathyroid hormone levels with mortality, residual kidney function and technical failure among patients on peritoneal dialysis. Clin. Kidney J. 16, 1957–1964 (2023).

Alrowiyti, I. M. & Bargman, J. A. Review of residual kidney function in peritoneal Dialysis patients. Indian J. Nephrol. 33, 239–246 (2023).

Phatthanasobhon, S. et al. Effectiveness of renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system blockade on residual kidney function and peritoneal membrane function in peritoneal Dialysis patients: A Network Meta-Analysis. Sci. Rep. 9, 19582 (2019).

Htay, H. et al. Biocompatible dialysis fluids for peritoneal dialysis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 10, CD007554 (2018).

Yohanna, S. et al. Effect of Neutral-pH, Low-Glucose Degradation Product Peritoneal Dialysis Solutions on residual renal function, urine volume, and Ultrafiltration: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 10, 1380–1388 (2015).

Nakayama, M. et al. Encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis in the era of a Multi-disciplinary Approach based on Biocompatible solutions: the Next-Pd study. Perit. Dial Int. 34, 766–774 (2014).

Dimitrov, Y. et al. CERA conversion to darbepoetin alfa in 154 hemodialysis patients. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 52, 1979–1985 (2020).

Locatelli, F. et al. Novel erythropoiesis stimulating protein for treatment of anemia in chronic renal insufficiency. Kidney Int. 60, 741–747 (2001).

Narita, I. et al. Hyporesponsiveness to erythropoiesis-stimulating agent in non-dialysis-dependent CKD patients: the BRIGHTEN study. PLoS One. 17, e0277921 (2022).

Gao, P. et al. Development of a novel immunoradiometric assay exclusively for biologically active whole parathyroid hormone 1–84: implications for improvement of accurate assessment of parathyroid function. J. Bone Min. Res. 16, 605–614 (2001).

Yang, W. et al. Association of kidney disease outcomes with risk factors for CKD: findings from the chronic renal insufficiency cohort (CRIC) study. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 63, 236–243 (2014).

Graham, J. W., Olchowski, A. E. & Gilreath, T. D. How many imputations are really needed? Some practical clarifications of multiple imputation theory. Prev. Sci. 8, 206–213 (2007).

White, I. R. & Royston, P. Imputing missing covariate values for the Cox model. Stat. Med. 28, 1982–1998 (2009).

Acknowledgements

The data reported were obtained from the Japanese Renal Data Registry (JRDR). We are thankful to all patients and medical staff who registered patient data in the JRDR database. The interpretation and reporting of these data is the responsibility of the authors and should not be viewed as an official policy or interpretation of the Japanese Society for Dialysis Therapy.

Funding

This work was supported by the JSDT and Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (Grant number: 24K06239) in the roles of manuscript conception, planning, and writing.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: TI, TH, and YI; Data acquisition: TI, TH, MA, NH, YI, and TKu; Data analysis: TI; Methodology: TI, TH, TKo, and YI; Supervision: HH, MA, NH, KT, YI, and TKu; drafting: TI; Interpretation: TH, TKo, HN, HH, KT, YI, and TKu.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

TI received a research grant from Kyowa Kirin Co., Ltd. and a consultation fee from GlaxoSmithKline. TH received a research grant from JSPS KAKENHI (Grant Number 19K03092 and 24K06239), and honoraria from Kyowa Kirin, Baxter, Terumo, and Torii Pharmaceutical. TKo received honoraria from Kowa, Torii, Sanwa Kagaku Kenkyusyo, and AstraZeneca. HN received speaker honoraria from Kyowa Kirin, Baxter, Terumo, Ono Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., Daiichi-Sankyo, and Kissei Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd. MA received honoraria from Kyowa Kirin, Baxter, Terumo, Mitsubishi Tanabe, Torii, Bayer Yakuhin, and Astellas. HH is a scientific advisor for Astellas Pharma, Bayer Yakuhin, Kyowa Kirin, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, and Torii Pharmaceutical and has obtained research funds from Chugai Pharmaceutical, Kyowa Kirin, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, and Torii Pharmaceutical and lecture fees from Astellas Pharma, Bayer Yakuhin, Chugai Pharmaceutical, Kissei Pharmaceutical, Kyowa Kirin, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, and Torii Pharmaceutical. KT received honoraria from Kyowa Kirin, Mitsubishi-Tanabe, Astellas, Torii, Bayer, Baxter, Kissei, and Chugai and endorsements from Kyowa Kirin, Baxter, Terumo, Torii, Chugai, and Bayer. YI received research grants and speaker honoraria from Chugai Pharmaceutical, Kyowa Kirin, Astellas Pharma, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, Bayer, and Torii Pharmaceuticals. TKu received research grants from Ono Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Kissei Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., speaker bureaus from Kyowa Kirin, Fuso Pharmaceutical Industries, Ltd., Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Corporation, Astellas Pharma Inc., AstraZeneca Plc., and Bayer Yakuhin Ltd. All the remaining authors have nothing to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Imaizumi, T., Hasegawa, T., Kosugi, T. et al. Renal anemia and hyporesponsiveness to ESA for preservation of residual kidney function in patients undergoing peritoneal dialysis. Sci Rep 15, 2689 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87456-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87456-z