Abstract

Hydrogen is recognized as a clean energy replacement for non-renewable fossil fuels, and the utilization of metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) for hydrogen storage has gained considerable interest in recent years. In this study, hydrogen storage in MOFs was estimated using white-box methods, namely group method of data handling (GMDH), genetic programming (GP), and gene expression programming (GEP), which are robust soft-computing methods known for generating innovative correlations. To this end, temperature, pressure, pore volume, and surface area were implemented as input parameters for constructing these robust correlations. After that, the superiority of the established correlations was demonstrated through multiple statistical and graphical error assessment. The results indicated, the GMDH model demonstrates the highest accuracy with root mean square error (RMSE), and mean absolute error (MAE) values of 0.410 and 0.307, respectively. However, the GEP model’s accuracy was comparable to that of the GMDH model. In addition, sensitivity assessment showed that the pore volume and the pressure exhibit the strongest linear and non-linear relationships, respectively, with the H2 storage in MOFs. This was demonstrated by a Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.5 and a Spearman correlation coefficient of 0.56, respectively. Furthermore, temperature had a minimal negative impact on the H2 storage in MOFs according to Pearson, Spearman, and Kendall coefficients. Finally, to confirm the findings of the GMDH model, the leverage approach was applied, demonstrating that 96% of the data falls within the acceptable region, confirming the statistical reliability of the developed models.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Lately, a stronger emphasis has emerged on exploring cleaner energy sources, such as methane (CH4) and hydrogen (H2), due to growing environmental concerns regarding the consumption of fossil fuels1. Hydrogen has been widely regarded as a potential replacement for fossil fuel systems, and significant efforts have been made to create efficient storage solutions for it2. Hydrogen possesses a significantly higher energy density compared to gasoline and produces no carbon dioxide emissions upon combustion3. Its plentiful availability makes it a compelling choice compared to other green energy sources like biofuels, nuclear energy, and solar energy.

Nevertheless, the hydrogen’s energy density in its volumetric form is relatively low unless it is compressed, which necessitates energy-intensive processes such as compression and liquefaction during hydrogen transportation and storage4. Compressed or liquefied hydrogen, which requires significant maintenance expenses is inadequate to satisfy the demands for different on-board purposes5. Thus, developing secure, and high-performance hydrogen storage systems is crucial to enhance the utilization of hydrogen in fuel cell technology6. Storing hydrogen in a condensed form through physisorption (surface adsorption) and chemisorption (chemical bonding to materials) offers benefits over storing hydrogen as a compressed gas or liquid6. The significant energy needed to release hydrogen from chemical bonds like hydrides restricts their broad applicability7. As a result, the examination of appropriate materials for hydrogen storage through physisorption has emerged as a vibrant field of research, with researchers investigating numerous materials, such as different types of carbon8, zeolites9, Liquid Organic Hydrogen Carriers (LOHCs), and metal-organic frameworks (MOFs)10. LOHCs provide an efficient alternative for hydrogen storage by reducing its volume and ensuring safe handling. Since the early 1980s, when research on LOHCs began with benzene/cyclohexane systems, a range of H2-lean LOHC materials has been developed. These include aromatic hydrocarbons such as toluene, biphenyl, naphthalenes, and dibenzyltoluene, as well as nitrogen-containing heterocyclic compounds like N-alkylcarbazoles and 2-(N-Methylbenzyl)pyridine11,12,13,14,15. The core principle of LOHC technology involves an exothermic hydrogenation process, where these materials, typically in liquid or low-melting solid form, are capable of undergoing reversible hydrogenation to store hydrogen at production sites and can release it through dehydrogenation at the locations where it is needed, using a catalyst. However, extracting hydrogen from LOHCs typically necessitates regenerating the organic carrier via a chemical process, which adds both complexity and cost16,17. MOFs another promising hydrogen storage method, have garnered significant interest because of their design flexibility18, exceptional permanent porosity19, and substantial pore volume20. In addition, MOFs with their simpler adsorption/desorption mechanisms, require less complex infrastructure, which can reduce overall cost. These frameworks signify a novel category of porous crystalline materials that can be synthesized using metal centers and organic ligands in a customizable manner. This synthesis approach yields a diverse array of chemical compositions and structural configurations, allowing for precise adjustment of their properties21. The inclusion of metal centers and organic linkers presents a wide variety of building blocks that can be modified by incorporating functional groups, replacing metallic elements, or combining different metals and linkers.

Regardless of major advancements in techniques for designing and modifying MOFs, numerous challenges continue to be faced in their practical development for effective application. Indeed, only a small percentage of MOFs have been successfully synthesized22. For instance, MOF-5, has 60% open space, allowing for the storage of organic molecules and gases within its structure23. In 2003, Professor Yaghi’s group24 reported MOF-5’s hydrogen storage capacity as 4.5 wt% at 78 K and 0.7 bar and 1.0 wt% at 298 K and 20 bar. Majid EL Kassaoui et al.3 recently altered Zn-MOF-5 by exchanging Zn with Cd and Mg, then adding Li, Be, and Na. Their density functional theory (DFT) studies showed gravimetric hydrogen densities of 5.41, 4.78, and 4.45 wt% for Li2-modified Mg-MOF-5, Zn-MOF-5, and Cd-MOF-5, respectively. The findings indicate that Li2-decorated M-MOF-5 (M = Zn, Cd, Mg) samples have good weight capacity and H2 adsorption energy.

While these studies highlight the vast number of potential MOFs, the amount of available experimental data represents only a small fraction of the possible MOFs. Performing tests on all MOFs across various temperature and pressure ranges is labor-intensive, costly, and impractical. However, it should be noted that the current experimental data covers only a small fraction of the vast number of potential MOF materials available. On the other hand, measuring the H2 storage capacity of a specific MOF with variable surface areas and across various pressure levels can be time-consuming and costly. Additionally, it can be highly influenced by experimental conditions and sample purity. Basdogan et al.25 conducted an extensive literature survey and found that the models commonly used for predicting the H2 storage capacity of MOFs rely on molecular simulation techniques. However, the use of computational modeling approaches becomes difficult for many real synthesized MOFs because of challenges like structural irregularities and decreased porosity. As a result, these materials are not readily suitable for computational modeling assessments.

Therefore, creating a forecasting model to estimate the H2 storage in MOFs holds significant importance26. ANNs are versatile tools that demonstrate remarkable performance and accuracy when employed in modeling various systems27. Yildiz and Uzun28 have introduced an alternative approach for estimating the H2 storage in MOFs. They proposed a method based on artificial neural networks (ANN), which they developed and applied to 13 distinct MOFs. In addition, Ahmed et al.29 extensively examined a wide range of real and hypothetical MOFs for H2 storage. They created a machine learning model to predict H2 storage values across a broad collection comprising 918,734 real and non-real MOFs extracted from 19 databanks. Moreover, Atashrouz and Rahmani30 developed a GMDH model to estimate H2 storage capacity in MOFs. Nevertheless, these data have not been extensively published for a large variety of MOFs, and they only complied 35 experimental data points to support the model’s development. Following that, Salehi et al.31 applied numerous intelligent algorithms to forecast the H2 storage capacity of MOFs. On one hand, their analysis was limited to a dataset comprising only 294 experimental data points. On the other hand, although their intelligent strategies were precise, the model operated as a black box, lacking a transparent mathematical formula. Although ANNs exhibit high levels of accuracy, they possess complex structures, and the resulting mathematical model typically involves only a subset of weights and biases. As a result, an ANN does not possess a straightforward mathematical form that directly relates the inputs to the model’s results32,33. The main difficulties involve the intricate process of implementing and analyzing the white-box models, which often demands substantial expertise and computational power. Moreover, these models might struggle to adapt to new or more complex situations. Nevertheless, white-box approaches offer significant insights and establish a strong basis for continued exploration in this field. In engineering applications, straightforward equations and correlations are often more desirable and practical.

To our knowledge, there is no white-box correlation that reliably predicts the H2 storage capacity of MOFs using such an extensive dataset, a wide range of MOFs, and this acceptable level of accuracy. Our current study concentrates on the creation of transparent models employing sophisticated white-box methodologies. Thus, robust soft-computing methodologies including genetic programming (GP), gene expression programming (GEP), and the group method of data handling (GMDH) are utilized to estimate the H2 storage capacity of MOFs. To accomplish this objective, 1186 experimental datasets covering a variety of MOFs are sourced from a range of literature. Temperature, pore volume, pressure, and surface area were treated as input variables, with H2 storage as the output. This comprehensive data demonstrates the model’s robustness and generalizability. Furthermore, our models are simple, practical, and highly efficient for engineering applications, especially when working with such a large dataset, a variety of MOFs, and this degree of accuracy. Figure 1 illustrates the workflow of the developed correlations in this study. In the next section, an overview of our compiled dataset is presented. Furthermore, an in-depth description of the creation of intelligent white-box algorithms is provided in Sect. 3. Moreover, Sect. 4 presents the equations for forecasting H2 storage employing GEP, GP, and GMDH approaches. After that, several graphical and statistical evaluations are implemented to measure the accuracy of robust correlations to forecast the H2 Storage in MOFs. In addition, three correlation coefficients including, Pearson, Spearman, and Kendall were calculated to assess the effect of four input variables on the H2 storage. Finally, the Leverage method was applied to identify potential outlier data and validate the best proposed model.

Data acquisition

In this research, an extensive collection of data sets, totaling 1186 data points, was utilized34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53. This extensive dataset, comprises pressure, surface area, temperature, and pore volume as input factors, and H2 storage value as the output factor. The datasets were collected from various literature sources to create models for predicting the H2 storage in MOFs. The training and testing groups were formed by randomly distributing the data points. In each of these models, a portion of the data (20%) was set aside to examine the model, while 80% was used to train the model54. The ranges and statistical analysis for the aforementioned data are provided in Table 1. Statistical parameters such as skewness and kurtosis are often used to attain a more profound insight into the scatter distribution of the collected measurements. Skewness is a metric that quantifies the lack of symmetry in the probability distribution compared to its mean. Moreover, kurtosis reveals the shape of a probability distribution and specifically assesses the tails of a random variable’s distribution55.

Modeling techniques

Genetic programming (GP)

Koza56,57 proposed an innovative evolutionary computing approach called genetic programming (GP) to automatically solve issues in different engineering disciplines. This robust algorithm inspired by nature can simulate systems characterized by a considerable degree of fuzziness. This method involves formulating an equation that describes the studied phenomenon to find solutions. GP systems feature tree-like structures. Nodes are categorized as either internal or external based on their positions. Internal nodes, which possess one or more inputs, provide operational functionality. The tree’s termination points are denoted by external nodes58. This dependable, biology-based technique employs a repetitive method to produce an accurate mathematical model. After entering the data, the initial step is to form a random population, followed by using an objective function to assess the model’s efficiency. Subsequently, parents exhibiting strong matching values are selected for modification using genetic operators, resulting in the generation of offspring55. Successive generations are produced similarly, with the fitness of each generation improving as desirable traits are selected and passed down to their offspring. The process concludes when the error criterion is met or the ultimate number of generations is reached. The flowchart for the GP algorithm is visually depicted in Fig. 2.

Gene expression programming (GEP)

Gene Expression Programming (GEP), introduced by Ferreira59 in 1999 has emerged as an advanced symbolic regression framework based on artificial intelligence. As an evolved and improved version of GP, it incorporates two key computational elements for regression processes: chromosomal data (genotype) and expression tree structures (phenotype). One of the significant advantages of the GEP approach is that it does not require the detection of a specific functional representation to determine the optimal estimation for real measurements. GEP is a comprehensive solution for genotype/phenotype analysis that merges the ease of use of genetic algorithms with the robust capabilities of genetic programming60. The initial step of this algorithm involves creating an initial population of solutions which can be done randomly or by incorporating input information specific to the problem61. Indeed, GEP utilizes linear chromosomes of fixed length along with expressive parse trees that vary in size and shape62. Chromosomes can contain a multitude of genes. Subsequently, each chromosome’s expression in the initial population is carried out, and the fitness is measured using a fitness function formula. Indeed, chromosomes with the highest performance have a higher likelihood of being chosen to advance to the subsequent generation. Following selection, they are replicated with alterations through the use of genetic operator59. Figure 3 displays a basic flowchart illustrating this technique.

Group method of data handling (GMDH)

Ivakhnenko63 originally introduced the group method of data handling, which is based on the principles of Darwin’s theory of natural selection. GMDH offers valuable insights into complex computational issues and effectively handles the non-linearity of networks by enabling the creation of accurate and clear correlations between input and output variables. It is highly effective for pattern recognition and predicting random processes in complex systems. This method, also known as a polynomial neural network (PNN), is considered as one of the most effective types of ANNs. The PNN consists of multiple layers, each containing several independent nodes63. Nodes in the following layers are formed by quadratic polynomial functions that integrate the nodes from the preceding layers. Ivakhnenko’s work demonstrated the optimal depiction of quadratic polynomial equations in the GMDH algorithm. Utilizing the Volterra-Kolmogorov-Gabor series, the method forecasts the connection between input variables and output in the following manner63,64:

Here, Yi represents the output, and xi,xj,…, and xk denote the inputs. In addition, a, bi, cij, and dij…k specify polynomial coefficients used in the algorithm, and M indicates the number of input variables. As a consequence, the output parameters will be organized into a matrix, as displayed below64:

By applying the least squares analysis technique, the constants in Eq. (2) are determined. To ensure accuracy, the forecasted values need to be similar to the measured values, thereby minimizing the squared difference from the actual data is illustrated below65:

Here, Nt denotes the number of elements in the training subset to develop the model, while M refers to the number of variables. By employing a quadratic polynomial, the following formulation will represent the general matrix equation64,66:

Here, the transpose of a matrix is indicated by T, and A stands for the vector containing the coefficients of the quadratic polynomial,\(A=[{a_0},{a_1},…,{a_5}]\),\(X=[{x_1},{x_2},…{x_M}]\) and,\(Y=[{y_1},{y_2},…{y_M}]\).

The least squares technique results in the solution of Eq. (4) in the following manner

The collected data is split into two segments: one for training and one for testing. The training dataset is employed to calculate the coefficients in Eq. (2), whereas the testing dataset is utilized to identify the optimal pairing of two variables. To achieve the optimal configuration of input variables in the polynomial functions, the testing subset is employed, ensuring the following requirements are met66:

If the previously stated condition is satisfied, the new independent parameter will be kept within the program’s memory. The program concludes at the iteration where the calculation reaches the minimum error. Figure 4 presents a functional flowchart for the GMDH algorithm.

Results and discussion

Mathematical correlations development

In this work, three strong correlations namely, the GP, GEP, and GMDH were formulated to estimate the H2 storage in MOF. Indeed, the benefit of these white-box methods is that their predictive capabilities can be readily assessed and utilized through clear and straightforward equations. Therefore, this study focuses on presenting the developed formulas for estimating hydrogen storage in MOFs using four input parameters: Pressure (bar), temperature (K), surface area (m2/gr), and pore volume (cm3/gr). The final network expressions are presented as follows:

The equations suggested by GMDH:

The equations suggested by GEP:

The equations suggested by GP:

Statistical model assessment

The capability of the presented models was measured using multiple statistical metrics namely root mean square error (RMSE), correlation coefficient (R2), mean bias error (MBE), mean absolute percentage error (MAPE), standard deviation (SD), and mean absolute error (MAE). Here are the descriptions of the measures listed67:

where, N signifies the magnitude of the databank, while \(Y_{i}^{{exp}}\) and \(Y_{i}^{{cal}}\) is the ith experimental and predicted value of the H2 storage, respectively. In addition, \({\bar {Y}_i}\) denotes the mean of experimental data. Table 2 summarizes the outcomes of the statistical error examination for all correlations employed in this study. It should be noted that although all the applied algorithms are effective, the GMDH model stands out as the most precise and robust. The MAPE values of 0.302 for the training dataset, 0.309 for the testing dataset, and 0.307 for the entire dataset indicate that the GMDH model yields the most exact forecast of H2 storage capacity. Furthermore, upon examining Table 2, it is evident that the GEP and GP models also demonstrate strong predictive capabilities. In terms of precision, the ranking of the proposed models is as follows:

GMDH > GEP > GP.

To assess our model in relation to existing models in the literature, as mentioned before, Yildiz and Uzun28 achieved an R² of 0.925 based on an analysis of 13 data points; however, their model lacked generalizability and could not be widely applied. Atashrouz and Rahmani30 achieved an R² of 0.88 by developing a GMDH model for predicting hydrogen storage capacity, using only 35 experimental data points. Additionally, Salehi et al.31 employed black-box models by integrating various distinct models with CMIS, achieving a fit with an impressive R² value of 0.98. However, their model was based on a relatively small dataset (294 samples) and did not employ a transparent, white-box approach, limiting the generalizability of their model. Compared to these models, our model represents an advancement in terms of the number of data points, the variety of MOFs used, and a balance between high accuracy and a simplified, more generalizable equation.

Graphical model assessment

To visualize a model’s performance, graphical analyses are used, including cross plots, error distribution, and cumulative frequency plots. Figure 5 presents the cross plots for all techniques proposed in this study. In this type of scatter plot, the predicted data points from a model are plotted versus the experimental data along a 45° line that passes through the origin. The reliability and precision of the model are indicated by how well the data points fit along this unit-slope line. The model’s accuracy improves as more data points cluster near this line. Based on this figure, all the models developed for predicting H2 storage demonstrate reliability and validity, as they show a favorable match between the forecasted and measured values. In addition, Fig. 6 displays the outcomes of the error distribution analysis for the implemented correlations in estimating H2 storage. As observed, all the developed models show a tight aggregation of data points near the zero-error line, indicating their accuracy.

Figure 7 shows a graphical depiction of cumulative frequency which was used to assess the performance of various correlations discussed in this study. These plots display the cumulative frequency of the data in relation to the absolute error to determine the percentage of data points that the models predict correctly. All models are closely aligned, but a closer look reveals that the GMDH model aligns more precisely with the vertical line and demonstrates superior accuracy. Based on Fig. 7, it can be deduced that the GMDH method outperforms other strategies by accurately predicting over 90% of all data points with an absolute error below 0.7 and over 70% of the forecasted data with an absolute error below 0.39.

Group error analysis

The group error chart depicts the performance of the models across numerous values of input variables. This method starts by categorizing independent variables into different ranges according to the extent of their variations. Figure 8 depicts the group error plots associated with the estimation of H2 storage using three different models. These models rely on four independent variables, namely temperature, pore volume, surface area, and pressure. Based on the observation from Fig. 8(a), all models demonstrate comparable performance in predicting H2 storage across the entire surface area range. From Fig. 8(a), the GMDH model shows the lowest prediction error in the surface area range of (1925–2797) m2/gr, whereas, for the GEP and GP models, this occurs in the range of )180–1052( m2/gr range. However, the highest prediction errors for all models are found within the )2797–3670( m2/gr) range. Figure 8b reveals that the highest errors are observed within the pressure ranges of (14.7–19.6) bar. As shown in Fig. 8c, all models perform similarly across all intervals, except for the GMDH model, which demonstrates a lower error than the others in the pore volume range of (1.14–1.52) cm3/gr. Additionally, from Fig. 8d the GMDH model’s prediction in the (77.5–85) K range exhibits less error compared to the other models.

Sensitivity assessment

A sensitivity analysis of the results is necessary to comprehend the importance of each input on the output. In this survey, three correlation coefficients including Pearson, Spearman, and Kendall were computed to evaluate the impact of four inputs: temperature, pressure, surface area, and pore volume on the output of the GMDH model, specifically H2 storage in MOFs. The Pearson method is more frequently employed in reservoir studies, and it also assesses the linear dependence between two variables. The Pearson correlation coefficient is a metric ranging from − 1 to 1. A coefficient of 1 indicates that X and Y are perfectly characterized by a linear equation, with all data points aligned along a straight line where Y grows as X grows. Conversely, a coefficient of -1 signifies that all data points align on a straight line, where Y declines as X rises68. The formula employed for this analysis is as below69,70:

Here, yi is the i-th output value and \(\bar {y}\) is the mean value of the forecasted outcome, and xj, i is the i-th value of j-th input and \(\bar {x}\)is the average of the j-th input. The equation for determining the Spearman coefficient is provided below71:

Here, n indicates the count of samples, and the rankings of the variables x and y are denoted as R(x) and R(y), respectively. Ra(x) and Ra(y) represent the average ranks of the variables x and y. Spearman’s correlation coefficient is commonly calculated to evaluate the nonlinear association between two variables using non-parametric statistics. This approach entails calculating the ranks of the actual values independently and subsequently finding their correlation. The principal contrast between the Pearson and Spearman coefficients is that the Pearson coefficient is limited only to linear relationships between variables, while the Spearman coefficient can handle non-linear relationships. It is also noteworthy that the Spearman coefficient deals with variables with a ranking order, while the Pearson coefficient uses raw data values. The formula for Kendall’s tau when ranks are tied is as below72:

where, \({\tau _B}\) represents Kendall’s tau adjusted for tied ranks. Na and Nd are the counts of order agreements and disagreements, respectively. N signifies the overall number of data points, whereas tx and ty denote the count of tied observations for the first and second variables, respectively. The mentioned correlations possess values spanning the range from − 1 to 1. These values characterize the orientation and intensity of the connection between two variables. Figure 9 presents the effect of the models’ inputs concerning the calculated values of H2 storage calculating Pearson, Spearman, and Kendall coefficients. The Pearson coefficient for temperature is −0.2, indicating a weak negative linear relationship with the H2 storage. Similarly, the Spearman and Kendall coefficients (−0.19 and − 0.14, respectively) also suggest that increased temperature slightly reduces H2 storage. Regarding pressure, the Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.39 suggests a positive linear association with H2 storage. The Spearman correlation coefficient of 0.56 and the Kendall coefficient of 0.45 indicate a strong positive relationship, suggesting that as the pressure rises, H2 storage tends to increase as well. In addition, the findings show that the Pearson correlation coefficient and Spearman coefficient between pore volume and H2 storage are 0.5 and 0.46 indicating a positive association between the two variables. This suggests that the relationship involves both linear and non-linear components, with the linear aspect being more prominent or significant. The Pearson coefficient is higher for surface area compared to other coefficients because the connection between this parameter and H2 storage is linear. The analysis indicates that pore volume and surface area significantly affect H2 storage, both showing a positive correlation. Overall, the linear relationship indicates that pore volume and surface area have a more significant influence on H2 storage capacity. However, considering the non-linear relationship, pressure exerts a greater impact on H2 storage.

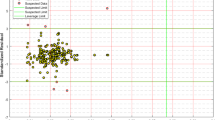

Leverage evaluation

The Leverage strategy is a proven approach for forecasting potential outlier data and assessing the credibility and applicability domain of a model73. In this work, the Leverage method is performed to ensure the correctness of the GMDH correlation for forecasting the H2 storage in MOFs. To determine the leverages of the inputs, the hat matrix should be introduced as follows74:

In this context, XT refers to the transpose of the two-dimensional matrix X with dimensions. (n×m). The standardized residuals are calculated using the formula27:

In the formula provided, the standardized residual value is depicted by Ri, MSE signifies the mean square error, zi stands for the error of the i-th data point, and Hii represents the hat indices. The warning leverage (H*) signifies the ratio expressed as 3(m + 1)/n, where m refers to the count of inputs in the model, and n expresses the count of data points68. Figure 10 displays William’s plot of the GMDH algorithm using standardized residuals (R) against Hat indices to evaluate the model’s reliability. Data points that fall outside the range \(- 3 \leqslant R \leqslant 3\) are classified as bad high leverage and are treated as outliers or suspected data. Moreover, data within the ranges of \(H \geqslant {H^*}\)and \(- 3 \leqslant R \leqslant 3\) are classified as good high leverage. The suitable domain is determined as the squared region within the standard deviations and the specified leverage limit of H. The large number of data points are observed to lie within the usability domains of the GMDH correlation, particularly within the ranges of \(- 3 \leqslant R \leqslant 3\) and \(0 \leqslant H \leqslant 0.0126\). Within the applicability region, over 96% of data points are situated. The outcomes imply that the GMDH correlation proposed in this study is significantly dependable when it comes to estimating H2 storage in MOFs.

Conclusions

This study utilized the GEP, GP and GMDH approaches to develop straightforward, scalable, and reliable models for estimating the H2 storage capacity of MOFs using a comprehensive dataset that includes 1186 experimental data points. The correlations were developed using pressure, pore volume, surface area, and temperature as inputs. The accuracy and validity of the correlations were examined by comparing them applying statistical error parameters as well as graphical approaches. The results showed that all established correlations were effective, but the GMDH correlation was found to be the most precise for predicting the H2 storage in MOF, achieving RMSE and MAE values of 0.4107 and 0.3077, respectively. The proposed models’ accuracy, ranked from highest to lowest, is in the order of GMDH, GEP, and GP. Additionally, three methods of sensitivity assessment (Pearson, Spearman, and Kendall coefficient) were implemented to explore the impact of input factors on H2 storage. Each of the input parameters, including pressure, pore volume, and surface area have a direct positive effect on the H2 storage. In contrast, temperature exhibits an inverse impact on the H2 storage. Besides, the sensitivity examination confirmed that the pore volume and the pressure exhibited the most significant linear and non-linear correlations with the H2 storage in MOFs. This was evidenced by the Pearson and the Spearman correlation coefficients of 0.5 of 0.56, respectively. However, pore volume and surface area have nearly identical absolute relative impacts on H2 storage. Finally, the Leverage method showed that only a small fraction of the measurement falls beyond the applicability range of the established correlations, with over 96% of the data consisting of accurate measurements. This work enables researchers to accurately identify and optimize MOFs for specific storage criteria, enhancing hydrogen storage efficiency through white-box methodologies and while also refining key parameters affecting H₂ storage. However, numerous MOFs remain unexplored for their potential in hydrogen storage. Expanding the range of MOFs studied could improve the model’s predictive accuracy. In addition, integrating a wider variety of computational analyses with experimental research in future work could offer deeper insights into hydrogen storage capabilities.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Bicer, Y. & Dincer, I. Clean fuel options with hydrogen for sea transportation: a life cycle approach. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy. 43 (2), 1179–1193 (2018).

Swesi, Y., Ronze, D., Pitault, I., Dittmeyer, R. & Heurtaux, F. Purification process for chemical storage of hydrogen for fuel cell vehicles applications. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy. 32 (18), 5059–5066 (2007).

Zhou, L. Progress and problems in hydrogen storage methods. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 9 (4), 395–408 (2005).

Yang, J., Sudik, A., Wolverton, C. & Siegel, D. J. High capacity hydrogen storage materials: attributes for automotive applications and techniques for materials discovery. Chem. Soc. Rev. 39 (2), 656–675 (2010).

Ahmed, A., Al-Amin, A. Q., Ambrose, A. F. & Saidur, R. Hydrogen fuel and transport system: a sustainable and environmental future. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy. 41 (3), 1369–1380 (2016).

Suh, M. P., Park, H. J., Prasad, T. K. & Lim, D. W. Hydrogen storage in metal–organic frameworks. Chem. Rev. 112 (2), 782–835 (2012).

Khafidz, N. Z. A. K., Yaakob, Z., Lim, K. L. & Timmiati, S. N. The kinetics of lightweight solid-state hydrogen storage materials: a review. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy. 41 (30), 13131–13151 (2016).

Darkrim, F. L., Malbrunot, P. & Tartaglia, G. P. Review of hydrogen storage by adsorption in carbon nanotubes. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy. 27 (2), 193–202 (2002).

Langmi, H. et al. Hydrogen adsorption in zeolites a, X, Y and RHO. J. Alloys Compd. 356, 710–715 (2003).

Wong-Foy, A. G., Matzger, A. J. & Yaghi, O. M. Exceptional H2 saturation uptake in microporous metal – organic frameworks. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128 (11), 3494–3495 (2006).

Biniwale, R. B., Rayalu, S., Devotta, S. & Ichikawa, M. Chemical hydrides: a solution to high capacity hydrogen storage and supply. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy. 33 (1), 360–365 (2008).

Oh, J. et al. 2-(N‐Methylbenzyl) pyridine: A Potential Liquid Organic Hydrogen Carrier with Fast H2 Release and Stable Activity in Consecutive Cycles, ChemSusChem. 11 (4), 661–665. (2018).

Sisakova, K., Podrojkova, N., Orinakova, R. & Orinak, A. Novel catalysts for dibenzyltoluene as a potential Liquid Organic hydrogen carrier use—A mini-review. Energy Fuels. 35 (9), 7608–7623 (2021).

Crabtree, R. H. Hydrogen storage in liquid organic heterocycles. Energy Environ. Sci. 1 (1), 134–138 (2008).

Emel’yanenko, V. N. et al. Hydrogen storage: thermochemical studies of N-alkylcarbazoles and their derivatives as a potential liquid organic hydrogen carriers. J. Phys. Chem. C. 119 (47), 26381–26389 (2015).

Bouchy, M., Peureux-Denys, S., Dufresne, P. & Kasztelan, S. Hydrogenation and hydrocracking of a model light cycle oil feed. 2. Properties of a sulfided nickel-molybdenum hydrocracking catalyst. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 32 (8), 1592–1602 (1993).

Oh, Y. et al. Selective hydrotreating and hydrocracking of FCC light cycle oil into high-value light aromatic hydrocarbons. Appl. Catal. A. 577, 86–98 (2019).

Yaghi, O. M. et al. Reticular synthesis and the design of new materials. Nature 423 (6941), 705–714 (2003).

Bradshaw, D., Prior, T. J., Cussen, E. J., Claridge, J. B. & Rosseinsky, M. J. Permanent microporosity and enantioselective sorption in a chiral open framework. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126 (19), 6106–6114 (2004).

Férey, G., Mellot-Draznieks, C., Serre, C. & Millange, F. Crystallized frameworks with giant pores: are there limits to the possible? Acc. Chem. Res. 38 (4), 217–225 (2005).

Ahmed, A. et al. Balancing gravimetric and volumetric hydrogen density in MOFs. Energy Environ. Sci. 10 (11), 2459–2471 (2017).

Moghadam, P. Z. et al. Development of a Cambridge Structural database subset: a collection of metal–organic frameworks for past, present, and future. Chem. Mater. 29 (7), 2618–2625 (2017).

Kassaoui, M. E., Lakhal, M., Benyoussef, A., Kenz, A. E. & Loulidi, M. Effect of zinc substitution by magnesium and cadmium on hydrogen storage properties of connector-metal-organic framework-5. J. Alloys Compd. 874, 159902 (2021).

Rosi, N. L. et al. Hydrogen storage in microporous metal-organic frameworks. Science 300 (5622), 1127–1129 (2003).

Basdogan, Y. & Keskin, S. Simulation and modelling of MOFs for hydrogen storage, CrystEngComm. 17 (2), 261–275. (2015).

Butler, K. T., Davies, D. W., Cartwright, H., Isayev, O. & Walsh, A. Maching Learning for molecular and mateials science. Nature. 559 (7715), 547–555. (2018).

Naghizadeh, A. et al. Modeling thermal conductivity of hydrogen-based binary gaseous mixtures using generalized regression neural network. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy. 59, 242–250 (2024).

Yıldız, Z. & Uzun, H. Prediction of gas storage capacities in metal organic frameworks using artificial neural network. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 208, 50–54 (2015).

Ahmed, A. & Siegel, D. J. Predicting hydrogen storage in MOFs via machine learning. Patterns. 2, 7. (2021).

Atashrouz, S. & Rahmani, M. Predicting hydrogen storage capacity of metal–organic frameworks using group method of data handling. Neural Comput. Appl. 32, 14851–14864 (2020).

Salehi, K., Rahmani, M. & Atashrouz, S. Machine learning assisted predictions for hydrogen storage in metal-organic frameworks. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy. 48 (85), 33260–33275 (2023).

Deymi, O. et al. Toward empirical correlations for estimating the specific heat capacity of nanofluids utilizing GRG, GP, GEP, and GMDH. Sci. Rep. 13 (1), 20763 (2023).

Hadavimoghaddam, F. et al. Application of advanced correlative approaches to modeling hydrogen solubility in hydrocarbon fuels. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy. 48 (51), 19564–19579 (2023).

Yan, Y. et al. High volumetric hydrogen adsorption in a porous anthracene-decorated metal–organic framework. Inorg. Chem. 57 (19), 12050–12055 (2018).

Sumida, K. et al. Hydrogen storage and carbon dioxide capture in an iron-based sodalite-type metal–organic framework (Fe-BTT) discovered via high-throughput methods. Chem. Sci. 1 (2), 184–191 (2010).

Orcajo, G. et al. Li-Crown ether complex inclusion in MOF materials for enhanced H2 volumetric storage capacity at room temperature. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy. 44 (35), 19285–19293 (2019).

Ibarra, I. A. et al. Highly porous and robust scandium-based metal–organic frameworks for hydrogen storage. Chem. Commun. 47 (29), 8304–8306 (2011).

Bambalaza, S. E., Langmi, H. W., Mokaya, R., Musyoka, N. M. & Khotseng, L. E. Experimental demonstration of dynamic temperature-dependent behavior of UiO-66 metal–organic framework: compaction of hydroxylated and dehydroxylated forms of UiO-66 for high-pressure hydrogen storage. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 12 (22), 24883–24894 (2020).

Xiang, Z. et al. Hydrogen storage in mesoporous coordination frameworks: experiment and molecular simulation. J. Phys. Chem. C. 113 (34), 15106–15109 (2009).

Dinca, M. et al. Hydrogen storage in a microporous metal – organic framework with exposed Mn2 + coordination sites. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128 (51), 16876–16883 (2006).

Sumida, K., Hill, M. R., Horike, S., Dailly, A. & Long, J. R. Synthesis and hydrogen storage properties of Be12 (OH) 12 (1, 3, 5-benzenetribenzoate) 4. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131 (42), 15120–15121 (2009).

Li, Y., Xie, L., Liu, Y., Yang, R. & Li, X. Favorable hydrogen storage properties of M (HBTC)(4, 4′-bipy)· 3DMF (M = Ni and Co), Inorg. Chem.. 47 (22), 10372–10377. (2008).

Park, H. J., Lim, D. W., Yang, W. S., Oh, T. R. & Suh, M. P. A highly porous metal–Organic Framework: structural transformations of a guest-free MOF depending on activation method and temperature. Chem. A Eur. J. 17 (26), 7251–7260 (2011).

Han, D. et al. A non-interpenetrated porous metal–organic framework with high gas-uptake capacity. Chem. Commun. 47 (35), 9861–9863 (2011).

Lin, K. S., Adhikari, A. K., Chang, K. C., Tu, M. T. & Lu, W. Hydrogen adsorption in metal organic frameworks by hydrogen spillover. Catal. Today. 164 (1), 23–27 (2011).

Molefe, L. Y. et al. Polymer-based shaping strategy for zeolite templated carbons (ZTC) and their metal organic framework (MOF) composites for improved hydrogen storage properties. Front. Chem. 7, 864 (2019).

Saha, D., Deng, S. & Yang, Z. Hydrogen adsorption on metal-organic framework (MOF-5) synthesized by DMF approach. J. Porous Mater. 16, 141–149 (2009).

Prasad, T. K., Hong, D. H. & Suh, M. P. High gas sorption and metal-ion exchange of microporous metal–organic frameworks with incorporated imide groups. Chem. A Eur. J. 16 (47), 14043–14050 (2010).

Calleja, G., Botas, J., Sánchez-Sánchez, M. & Orcajo, M. Hydrogen adsorption over Zeolite-like MOF materials modified by ion exchange. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy. 35 (18), 9916–9923 (2010).

Saha, D., Wei, Z. & Deng, S. Equilibrium, kinetics and enthalpy of hydrogen adsorption in MOF-177. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy. 33 (24), 7479–7488 (2008).

Yang, S. J., Jung, H., Kim, T., Im, J. H. & Park, C. R. Effects of structural modifications on the hydrogen storage capacity of MOF-5. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy. 37 (7), 5777–5783 (2012).

Khoshhal, S., Ghoreyshi, A. A., Jahanshahi, M. & Mohammadi, M. Study of the temperature and solvent content effects on the structure of Cu–BTC metal organic framework for hydrogen storage. RSC Adv. 5 (31), 24758–24768 (2015).

Adhikari, A. K., Lin, K. S. & Tu, M. T. Hydrogen storage capacity enhancement of MIL-53 (cr) by pd loaded activated carbon doping. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 63, 463–472 (2016).

Krzywinski, M. & Altman, N. Points of significance: visualizing samples with box plots. Nat. Methods. 11, 2. (2014).

Naghizadeh, A., Larestani, A., Amar, M. N. & Hemmati-Sarapardeh, A. Predicting viscosity of CO2–N2 gaseous mixtures using advanced intelligent schemes. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 208, 109359 (2022).

Koza, J. R. Evolution of subsumption using genetic programming, In Proceedings of the first European conference on artificial life. MIT Press Cambridge, 110–119. (1992).

Koza, J. R., Bennett, F. H. III, Andre, D. & Keane, M. A. Genetic programming: biologically inspired computation that creatively solves non-trivial problems. In Evolution as Computation: DIMACS Workshop. Springer, 95–124. (2002).

Suh, C., Choi, B., Lee, S., Kim, D. & Cho, J. Application of genetic programming to develop the model for estimating membrane damage in the membrane integrity test using fluorescent nanoparticle, Desalination. 281, 80–87. (2011).

Ferreira, C. Gene expression programming: a new adaptive algorithm for solving problems. arXiv. (2001).

Faradonbeh, R. S., Armaghani, D. J., Monjezi, M. & Mohamad, E. T. Genetic programming and gene expression programming for flyrock assessment due to mine blasting. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 88, 254–264 (2016).

Rostami, A., Hemmati-Sarapardeh, A. & Mohammadi, A. H. Estimating n-tetradecane/bitumen mixture viscosity in solvent-assisted oil recovery process using GEP and GMDH modeling approaches. Pet. Sci. Technol. 37 (14), 1640–1647 (2019).

Ferreira, C. Gene expression programming in problem solving. In Soft Computing and Industry: Recent Applications. Springer, 635–653. (2002).

Ivakhnenko, A. G. Polynomial theory of complex systems. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man. Cybern. 4, 364–378 (1971).

Dargahi-Zarandi, A., Hemmati-Sarapardeh, A., Hajirezaie, S., Dabir, B. & Atashrouz, S. Modeling gas/vapor viscosity of hydrocarbon fluids using a hybrid GMDH-type neural network system. J. Mol. Liq. 236, 162–171 (2017).

Ivakhnenko, A. Modeling of complex systems from experimental data((Russian book))(Modelirovanie slozhnykh sistem po eksperimental’nym dannym). Mosc. Izdatel’stvo Radio Sviaz’. 120, 1987. (1987).

Hemmati-Sarapardeh, A. & Mohagheghian, E. Modeling interfacial tension and minimum miscibility pressure in paraffin-nitrogen systems: Application to gas injection processes, Fuel 205, 80–89. (2017).

Shahabi-Ghahfarokhy, A., Nakhaei-Kohani, R., Amar, M. N. & Hemmati-Sarapardeh, A. Modelling density of pure and binary mixtures of normal alkanes: comparison of hybrid soft computing techniques, gene expression programming, and equations of state. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 208, 109737 (2022).

Lv, Q. et al. Modeling thermo-physical properties of hydrogen utilizing machine learning schemes: viscosity, density, diffusivity, and thermal conductivity. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy. 72, 1127–1142 (2024).

Hosseinzadeh, M. & Hemmati-Sarapardeh, A. Toward a predictive model for estimating viscosity of ternary mixtures containing ionic liquids. J. Mol. Liq. 200, 340–348 (2014).

Chen, G. et al. The genetic algorithm based back propagation neural network for MMP prediction in CO2-EOR process. Fuel 126, 202–212 (2014).

Xu, M., Wong, T. C. & Chin, K. S. Modeling daily patient arrivals at Emergency Department and quantifying the relative importance of contributing variables using artificial neural network. Decis. Support Syst. 54 (3), 1488–1498 (2013).

Esmaeili, A. et al. Insights into modeling refractive index of ionic liquids using chemical structure-based machine learning methods. Sci. Rep. 13 (1), 11966 (2023).

Rousseeuw, P. J. & Leroy, A. M. Robust Regression and Outlier Detection Wiley. (2005).

Mousavi, S. P. et al. Viscosity of ionic liquids: Application of the Eyring’s theory and a committee machine intelligent system, Molecules. 26, (1), 156. (2020).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.N.: Investigation, Visualization, Writing-Original Draft, F.H.: Conceptualization, Validation, Modeling, S.A.: Writing-Review & Editing, Methodology, Data curation, Supervision, A.A.: Writing-Review & Editing, Validation, Data curation, Visualization, M.E.: Writing-Review & Editing, Data curation, conceptualization, Methodology, A.M.: Writing-Review & Editing, Validation, Supervision, A.H-S.: Methodology, Validation, Supervision, Writing-Review & Editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Naghizadeh, A., Hadavimoghaddam, F., Atashrouz, S. et al. White-box methodologies for achieving robust correlations in hydrogen storage with metal-organic frameworks. Sci Rep 15, 4894 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87495-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87495-6