Abstract

The oral cancer treatment of choice is surgical excision with an organ preservation, if it is possible. Radiation therapy is commonly used as a postoperative treatment. Delivering radiation dose during surgery, defined as intraoperative radiotherapy (IORT), can be very useful especially in case of high risk of recurrence or where gross or macroscopic residual disease are present. The aim of this retrospective study is to evaluate the effectiveness of IORT combined with postoperative fractionated irradiation (EBRT) of patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity. The study included 23 patients: IORT dose of 5–7.5 Gy was delivered using 50 kV X-rays generated by INTRABEAM™, combined with EBRT of 50–60 Gy in 25–30 fractions depending on presence of extracapsular invasion and narrow or positive surgical margins. Standard statistical tests were used. Median follow up was 64 months (range 8–222 months). The 5-year local tumour control was 92% and 82.5% in the 10-year follow-up. The 5-year overall survival (OS) was 56% and decreased to 45% during the next 5 years. There were no differences in the LTC, DFS and OS regarding sex, T-stage, grade and tumour localization, although a small group of analysed cases may raise some uncertainties. Acute side effects of combined IORT and EBRT were mild and no late complications occurred. The present study indicated that low-energy X-rays IORT combined with postoperative EBRT is a feasible and safe therapeutic modality which likely reduces a risk of locoregional recurrences.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Various radiotherapy methods of ‘boost dose’ (e.g. concomitant boost brachytherapy, chemo-acceleration) have been developed and validated in the clinic to improve local tumour outcomes, especially in case of high risk of local recurrences following conventional irradiation.

Intraoperative radiotherapy (IORT) is one of the interesting solutions. Over the past three decades, interest in IORT has gone and is now coming back again. New enthusiasm for IORT has arisen due to the development of compact and portable electron or X-ray beam facilities (INTRABEAM™ machines). IORT remains a unique and attractive treatment method for selected patients to improve local tumour control of locally advanced cancers1,2,3,4. It has several advantages, including immediate start of radiation at the time of surgery, strict cooperation with the surgeon, and a conformity of a boost dose. The IORT has often been used for patients with breast cancer and other deep-seated tumours such as gastric, pancreatic, and rectal cancers, and is regarded as an intraoperative boost dose prior to postoperative fractionated radiotherapy. The effective use of IORT requires a multidisciplinary approach, including close cooperation between surgeons, radiation oncologists, clinical oncologists and physicists. However, despite promising clinical data, there is a lack of large prospective trials, except for breast cancer. There are several publications that present the use of IORT in oral cavity squamous cell cancer to treat primary or recurrent tumours5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19.

This study aims to present our experience and evaluate the effectiveness of the IORT for oral cavity patients.

Materials and methods

All consecutive patients who received IORT in our cancer centre during the treatment of oral cancer were included into analysis. The main inclusion criteria for IORT was the diagnosis of oral cavity cancer preoperatively assessed as a potentially microscopically doubt by the surgeon. Lack of informed consent, large tumour volume, no operating conditions during surgery, and gross microscopic margin involvement were the main exclusion criteria. From 2003 to 2019 a total number of 23 patients with pathologically proven oral cavity squamous cell cancer (14 localized on the mobile tongue, 9 in the floor of the month) have been treated with surgery, IORT and postoperative radiotherapy. According to TNM, 13 tumours were in stage T1, nine in T2 and one in T3 stage. There were 18 cases with N0, two with N1, two with N2 and one case with N3 stage. Tumour volume ranged from 0.03 cc to 67.78 cc (median 1.26 cc). Stage M0 was proven in all cases based on X-ray and ultrasound (USG) images. The patient’s age raged from 38 to 84 years, with a median of 63 (IQR 14). The male to female ratio was 1.6:1. No adjuvant treatment was administered. Such slow recruitment of patient was an effect of progressive changes in surgery and the implementation of reconstructive procedures that modified the indications for radiotherapy. Even though X-ray therapy was a well-established treatment in Poland in the early 2000s, during screening each patient was informed about the specificity of the method, its expected benefits and side effects. All patients also had the opportunity to get answers to any questions. In case of patient doubts or lack of informed consent, only postoperative EBRT boost was used.

The study was approved by the ethical committee at the MSC National Research Institute of Oncology in Gliwice (number: KB/KB/430-70/23) and performed according to the Helsinki Declaration and treatment protocol of Maria Sklodowska-Curie National Research Institute of Oncology, branch Gliwice. The protocol of the pilot study was approved by the institutional ethics committee in 2003.

Treatment

All patients underwent tumorectomy, which was combined in nine cases with some type of reconstruction or plastic surgery to restore topography and function of surrounding healthy tissues. In four cases free cutaneous transfers were used, pedicle submental flap in three cases, free fibular flap in one case, and transverse tongue flap in one case. The type of surgery and reconstruction depended on the extent of the disease and the size of the resection, and the surgical team’s decision. Based on the initial clinical stage and the results of intraoperative lymph node biopsies, lymph node dissection was performed in 20 cases. In each case, margin status was determined during surgery by frozen section. Decision of surgical extension or IORT implementation was making immediate by the surgeon and radiation oncologist based on the intraoperative report. Patients were considered eligible for IORT due to their narrow surgical margins, which suggested nonradical microscopically tumour dissection, or intraoperative biopsies that demonstrated histologically positive margins. Both of these factors are risk factors for local recurrence. The decision of combined treatment (high dose external beam radiotherapy (EBRT) + IORT) was preferred in these cases over mutilating surgery and approved by the surgeon. Definitive margins were confirmed later in the final pathology.

IORT

When pathological or surgical risk margins were defined and the diameter of the tumour bed was measured, an adequate spherical applicator in the size range of 2 - 4 cm,was put in the tumour bed area. . The applicator’s diameter was precisely determined to encompass the entire high-risk area. The target for the IORT boost was defined as the tumour bed. Due to the specificity of the technique and the device, it was not possible to vary the dose in different directions depending on the size of the margins. The dose selection process considered margin status (main factor increasing dose), volume of tumour bed (applicator size), proximity to critical structures. Due to lack of final pathology, decision-making of dose was based on frozen section probe: for positive or close (< 1 mm in frozen section) margin dose 7 to 7.5 Gy was given, for negative, 5 Gy as standard dose was delivered. In result, there was no need to reduce dose because of the tumour bed size and nearby critical structures. A single dose of 5–7.5 Gy was delivered with a 50 kV X-ray beam generated by INTRABEAM™, measured at a distance of 5 mm from the surface of applicator. It is difficult to compare the clinical effectiveness of a single X-ray dose with a RBE of 1.4 with a fractionated dose of photon with a RBE of 1.020,21. For this purpose, the IORT dose was normalized (EQD2) if it was given in 2.0 Gy fractions using the α/β value of 10 Gy using the formula:

The calculated biological dose of IORT was on average 11.95 izoGy2.0 (8.7 izoGy2.0 − 15.2 izoGy2.0).

The median treatment time was 13 minutes (range 6.5–19.5 min). The IORT procedure was described in our previous articles and has not changed since 20035,22.

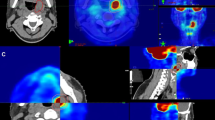

External beam radiotherapy (EBRT)

Postoperative 3D radiotherapy usually used a total dose of 50 Gy delivered in 25 fractions. In most cases (17 patients) the dynamic techniques (intensity modulated radiotherapy—IMRT) were used, 3D conformal techniques (3D CRT) were used rarely (6 patients) (mainly for patients treated in the first years of the study when it was a standard technique). Clinical target volume included the tumour bed and lymph nodes areas. The total dose (TD) was escalated to 60 Gy in 30 fractions for patients with extracapsular invasion and narrow or positive surgical margins. Only in one case, EBRT was not used (patient with a small tumour and no other risk factors in the final pathology). The median time between IORT—surgery and EBRT was 53 days (range 30–134, IQR—17 days. Finally, the total normalized dose of both radiation treatments was between 62.95 and 72.95 izoGy2.0 (58.7 izoGy – 75.2 izoGy2.0).

Details of the clinical characteristics of the patients and parameters of radiotherapy are shown in Table 1.

Study end points

In all patients, early and late toxicity was evaluated. Two scales were used: Dische and RTOG. The early mucosal side effects were scored using the Dische scale (14 points on the Dische correspond to confluent mucositis—CM). The RTOG scale was used to evaluate late effects. Mild and clinically irrelevant symptoms were accounted for.

During the follow-up period, patients had check-up visits and regular examinations were performed, including physical examination and computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) if necessary. Local recurrences within the irradiated area were confirmed trough biopsy and histopathological examination. Periodically, chest radiographs and abdominal sonography were used to exclude distant metastases.

Local tumour control (LTC) was defined as the time without local recurrence within the irradiated tumour bed area and calculated from the final day of EBRT. Disease-free survival (DFS) was calculated from the last day of EBRT to any (local or distant) relapse or death from any case. Overall Survival (OS) was calculated from the last day of EBRT to the day of death or loss from the observation (censored data) or the date of the last follow-up visit. LTC, DFS and OS estimates were calculated using the Kaplan Maier method. Univariate analysis to test the significance of the results was performed using log rank test and Chi-square tests.

Results

The median follow-up was 64 months (range 8–222 months, IQR 150). Only one patient was withdrawn from follow up due to interrupted treatment. All patients underwent complete gross tumour resection, with 95% achieving negative surgical margins. None of the patients had reoperation. The early tolerance of IORT was good as only 5 patients experienced superficial mucosal erosion due to the small distance between the mucosa and the applicator surface (where the contact dose is higher than the prescribed dose). This lesions were self-healing and did not required any surgical procedures. The early mucosal reactions during EBRT were mild, with a median Dische score of 11 (range 1–15, IQR 4). These reactions generally started to heal at the end of combined treatment. No significant serious late effects (grade 3 or 4 on the RTOG scale) were observed.

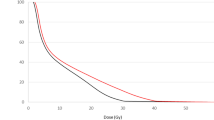

During the follow-up one patient experienced local recurrence (4.5%), two had nodal metastases (9%) and one patient (4.5%) had both local and nodal recurrence. Distant metastases were diagnosed in two patients, in one in the lung, and the other in the bones. The overall 5-year LTC was 92% and decreased to 82.5% during the next 5 years (Fig. 1). In the statistical analysis, we did not find significant differences regarding sex, stage T, tumour grade, tumour localization and IORT boost dose. The pathological status (positive or negative) and the time interval between surgery and EBRT have no impact on the risk of recurrence. However, looking at the total normalized dose of both radiation treatments delivered, statistically significant impact on DFS was found (p = 0.028, HR 0.97) with no impact on OS or LTC (p = ns). Five-year overall survival was 56% and 46% of 10-year OS, respectively. 5 and 10-year DFS was 52% and 40%, respectively (Fig. 2).

Discussion

Although head and neck cancers are not the leading tumours in terms of morbidity, they continue to be a subject of intensive and challenging studies of various radiation therapy regimens with the aim of improving treatment efficacy. Cancers of the tongue or floor of the mouth, even in their early stages, are associated with a relatively high risk of local and/or nodal recurrence. That risk is significantly increased by the presence of positive surgical margins4. Aggressive radical surgery can likely minimise that risk but, it has a significant detrimental impact on speech and swallowing dysfunctions and, consequently, on the physical and psychological quality of a patient’s life. Therefore, surgery is often combined with different types of radiotherapy and chemotherapy in order to minimize the risk of recurrence10,14,15,23,24,25.

Various strategies have been employed to escalate the radiation dose without extending the overall time of radiation, focusing on one extra fraction dose during the last two and half weeks of radiation (concomitant boost) or brachytherapy, chemo-acceleration directly after completing the EBRT23,24,25,26,27. Intraoperative radiotherapy was introduced nearly 50 years ago as a promising technique for boosting irradiation of tumours in various localizations. This method has been well documented as being highly effective6,7,8,9,11,13,17,18. However, it was not used as frequently for patients with head and neck cancers as for other tumour localizations, and even less frequently for patients with tongue and floor of mouth cancers15,16.

Despite that, it seems that IORT is an attractive modality of radiation for both surgeons and radiotherapists who cooperate in the head and neck cancer team for a few reasons10. First, in the case of inadequate surgical margins confirmed intraoperatively, this allows for intensifying the treatment and sterilizing the tumour bed from cancer cells. Secondly, the timing and precision of radiation delivery during surgery to the microscopic disease area indicated by the surgeon. An additional favourable aspect of IORT is the possibility of defining the high-risk area and minimising geographic errors, which are crucial after reconstructive surgery.

Another rationale for using IORT is the reduction in the treatment time. Protracted time of adjuvant radiotherapy, especially by the boost dose administered in the last days of treatment, is fundamental to increasing the probability of failure due to accelerated tumour cells repopulation. IORT reduces the duration of radiotherapy, and in most cases diminishes the gap between surgery and adjuvant RT7,8,9,20,28. Due to its conformity, IORT also limits the volume of healthy tissues exposed to radiation compared to conventional EBRT8,11.

The main disadvantage of single IORT doses is that they are less effective at killing the cells in the radioresistant phase of the cell cycle5,9. However, during fractionated radiotherapy, these cells can transfer into the radiosensitive phase and be reoxygeneted as well. Combinations of IORT followed by EBRT, as demonstrated in our study, are radiobiologically reasonable8.

A significant advantage of the low dose X-ray IORT over other IORT delivery methods such as electron beam or brachytherapy is its theoretically superior biological effectiveness. This is a consequence of the dosimetric characteristics of the INTRABEAM™ system applicators, the biological effects of a large single dose, and the higher RBE. Due to the dose fall off, the tissue contact dose at the applicator surface is significantly higher than the prescribed (at 5 mm), in fact. The smaller the applicator, the higher the dose on its surface. Therefore, if a standard dose of 5 Gy is prescribed at a specified 5 mm, it delivers a dose of 7–12 Gy on the surface. Given the increased surface dose and high RBE of X-ray radiation, the biological dose within the tumour bed is significantly higher than prescribed and is comparable to those given in high dose rate brachytherapy and radiosurgery boosts with all its consequences.

It is therefore not surprising that the present study pertains to patients who were treated with IORT for a duration of 16 years and who were individually qualified for that method of boost. For the treatment of our patients, we used an INTRABEAM™ system that generate 50 kV X-rays. In contrast to electron beam accelerators, INTRABEAM™, does not require expensive radioprotective adaptations in the operating theatre. It is also mobile and can be used in multiple rooms. Moreover, the X-ray beam characterizes a higher RBE (ranging from 1.4 to 3.5) compared to the electron beam20,21. For the present group of patients, the biologically normalized median dose IORT as if it were given in 2.0 Gy fractions was 11.95 izoGy2.0 (range 8.7 izoGy2.0 − 15.2 izoGy2.0). The duration of the IORT combined with postoperative EBRT has been found to be an important prognostic factor for therapeutic efficacy. Therefore the duration of interval between IORT therapy and EBRT plays a significant role. A study conducted on the IORT technique applied to early breast cancers patients has demonstrated that in patients at high risk for local or distant failures, IORT surgery and EBRT intervals shorter than 60 days resulted in no local recurrences. In contrast, for longer intervals, the rate of local recurrences increased to approximately 12%29. Among the present group of patients with cancer of the tongue and floor of the mouth, the median time interval was approximately 50 days.

The 5-year local tumour control of 82% in the present study (Fig. 1) is satisfactory, and it is higher than reported in other IORT studies15,16. It is possible that this is due to a relatively homogeneous group of patients (all were treated primarily and curatively), and despite the long period of 16 years during which patients were recruited in the protocol, the methods of therapeutic modalities were maintained unchanged.

This study has some limitations. Due to the small sample size of the present study, it may rise some questions regarding its significance. However, the method was applied to highly selected patients, which was reflected by a small study group during the 16-year recruitment period. Even with the conditions that were present at the beginning of our study (early 2000s), it would be extremely difficult to increase the number of the study group. Moreover, the standards of surgery (advances in reconstructive surgery) and adjuvant treatment have changed (for instance radiochemotherapy in N+ patients, competing high-precision EBRT).

The low 5-year OS of 56% may be surprising; however during the initial years of the IORT applications, the recruited patients were aged close to or exceeding 75 years. This may explain why the OS decreased by 44% in the first five years of follow-up and only by 10% in the next five years (Fig. 3). The number of all cases is too small to exclude patients, let say patients over 60 years old, because a much smaller set of cases would definitely raise justified uncertainty. The five-year DFS was also unexpectedly low (52%), but it was defined as any failure or death for any reason, and the main cause of this is mentioned patients’ advanced age, which is why deaths from natural causes influenced the decrease of DFS, as well as OS.

In general, it is difficult to compare these results to other studies because IORT is not commonly used in the case of patients with head and neck cancer, and there are no randomized studies evaluating clearly the effectiveness of such treatment. Regrettably, also there are no published studies comparing face-to-face IORT with other boost modalities for patients with oral cancer. Head and neck cancers are a heterogeneous group, and it is hard to compare them if they do not involve the same organ. Postoperative treatment encompasses additional parameters beyond radiation therapy alone or radiation therapy combined with chemotherapy or other biological agents, but without surgical intervention. An additional difficulty is the fact that in the available literature, even in the case of head and neck cancer patients, IORT was used in various modifications and localizations. In some studies, it was delivered as an electron beam, while in others as HDR brachytherapy. In less frequent instances, it was performed using low-energy kV, such as in our centre8,11. Considering the aim of treatment, in contrast to our study, IORT was used much more often as part of salvage or palliative treatment in the management of tumour recurrence after definitive therapy10. Differences also concern the anatomical sites of the tumour, and the wide range of doses administered8,11.

Although the analysed group was not treated under a rigid prospective study protocol, it was quite homogeneous in terms of localization, histopathology, treatment regimen and doses used, in contrast to others. The differentiating feature is the usage of orthovoltage radiation.

In this study, 5-year local tumour control was comparable to results observed by other authors using different boost modalities. Blažek et al. used stereotactic boost (2 × 5Gy) and reported 5-year LTC 62%30. Also Yamazaki et al. performed Cyber Knife based stereotactic boost and observed 5-year LTC of 71%, but the subgroup of oral cancer patients was relatively small (3 patients)31. These encouraging results and continuous technological progress, make stereotactic techniques a very promising option for irradiation boost. Hsieh et al. collected outcomes of 196 oral cancer patients irradiated postoperatively using sequential or simultaneous integrated (SIB) external beam boost and showed 5 year LTC of 90% vs. 74% and the difference was statistically significant32. Interstitial brachytherapy is another boost delivering technique, often being used for oral cavity cancers. Lapeyre et al. published results of 46 oral cavity cancer patients treated with EBRT and brachytherapy boost and reported 92% LTC at 5 years33. In addition, Beitler et al. demonstrated a series of 29 patients treated with brachytherapy boost. Local tumour control was 93%34. Although BT is very effective and gives high local control rates, it usually involves the need for another ‘small surgery’ procedure with general anaesthesia and the risk of surgical complications.

Among those who experienced acute side effects, all were scored as very mild according to the Dische scale. None of the patients experienced serious late complications such as osteonecrosis of the mandible or rupture of the artery. According to the literature, a dose of IORT below 15 Gy is safe in the majority of cases, which is higher than the dose given to our patients35. Furthermore, in the analysed group, the locations of tumour beds were distant from the carotid and usually separated enough from bone to receive high dose. The good treatment tolerance demonstrated that low-energy X-ray IORT with a dose of 5–7.5 Gy could be considered a safe method for boost therapy.

Over the past decade, stereotactic hypofractionated radiotherapy (SHRT) has been demonstrated to be highly effective and has emerged as a compelling alternative to IORT. Despite that, both therapeutic modalities are restricted to relatively small local tumours36. However, it does not eliminate the use of IORT, but the time between IORT surgery and EBRT should be as short as possible. If the duration is very prolonged, the biological efficacy of the IORT dose will be diminished, thereby increasing the likelihood of local recurrence and distant failure. However, due to the small number of cases included in the present study, it is not possible to evaluate the effect of the IORT dose.

Considering the encouraging results of our study and its comparable efficacy with other boost modalities reported by the cited authors, it seems justified to confirm the efficacy of IORT boost in a prospective multicentre clinical trial comparing it with SBRT or BT boost.

Conclusions

Low-energy X-ray IORT applied as a boost to conventionally fractionated radiotherapy is a safe and effective therapeutic modality for patients with oral cavity cancer. IORT likely reduces the risk of local recurrences, but the time interval between surgery and EBRT should be as short as possible and therefore should be planned, before the start of combined therapy. To clearly confirm the effectiveness of the IORT boost for oral cavity cancer patients, a further prospective multicentre clinical trial is needed.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- IORT:

-

Intraoperative radiotherapy

- EBRT:

-

External beam radiotherapy

- TNM:

-

Tumour, node, metastasis

- USG:

-

Ultrasonography

- RBE:

-

Relative biological effectiveness

- EQD2 :

-

Equivalent dose in 2 Gy fractions

- 3D CRT:

-

Three dimensional conformal radiotherapy

- TD:

-

Total dose

- RTOG:

-

Radiation therapy oncology group

- CM:

-

Confluent mucositis

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- LTC:

-

Local tumour control

- DFS:

-

Disease-free survival

- OS:

-

Overall survival

- RT:

-

Radiotherapy

- HDR:

-

High dose rate

- BT:

-

Brachytherapy

- SIB:

-

Simultaneous integrated boost

- SHRT:

-

Stereotactic hypofractionated radiotherapy

References

Seinsell, T. J. Intaoperative radiotherapy. In Perez And Brady’s Principles and Parctice of Radiation Oncology 7th edn 371–379 (Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott, 2019).

Most, M. D. et al. Feasibility of flap reconstruction in conjunction with intraoperative radiation therapy for advanced and recurrent head and neck cancer. Laryngoscope 118, 69–74. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLG.0b013e3181559ff7 (2008).

Pilar, A., Gupta, M., Ghosh Laskar, S. & Laskar, S. Intraoperative radiotherapy: Review of techniques and results. Ecancermedicalscience 11, 750. https://doi.org/10.3332/ecancer.2017.750 (2017).

Ravasz, L. A., Slootweg, P. J., Hordijk, G. J., Smit, F. & van der Tweel, I. The status of the resection margin as a prognostic factor in the treatment of head and neck carcinoma. J. Craniomaxillofac. Surg. 19, 314–318. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1010-5182(05)80339-7 (1991).

Rutkowski, T. et al. Intraoperative radiotherapy (IORT) with low-energy photons as a boost in patients with early-stage oral cancer with the indications for postoperative radiotherapy: Treatment feasibility and preliminary results. Strahlenther. Onkol. 186, 496–501. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00066-010-2117-2 (2010).

Villafuerte, C. V. L. 3rd., Ylananb, A. M. D., Wong, H. V. T., Cañal, J. P. A. & Fragante, E. J. V. Jr. Systematic review of intraoperative radiation therapy for head and neck cancer. Ecancermedicalscience 16, 1488. https://doi.org/10.3332/ecancer.2022.1488 (2022).

Marucci, L. et al. Intraoperative radiation therapy as an “early boost” in locally advanced head and neck cancer: Preliminary results of a feasibility study. Head Neck 30, 701–708. https://doi.org/10.1002/hed.20777 (2008).

Kyrgias, G. et al. Intraoperative radiation therapy (IORT) in head and neck cancer: A systematic review. Medicine (Baltimore) 95, e5035. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000005035 (2016).

Carter, Y. M., Jablons, D. M., DuBois, J. B. & Thomas, C. R. Jr. Intraoperative radiation therapy in the multimodality approach to upper aerodigestive tract cancer. Surg. Oncol. Clin. N. Am. 12, 1043–1063. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1055-3207(03)00089-9 (2003).

Scala, L. M. et al. Intraoperative high-dose-rate radiotherapy in the management of locoregionally recurrent head and neck cancer. Head Neck 35, 485–492. https://doi.org/10.1002/hed.23007 (2013).

Hilal, L. et al. Intraoperative radiation therapy: A promising treatment modality in head and neck cancer. Front. Oncol. 7, 148. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2017.00148 (2017).

Yang, Y. et al. A prospective, single-arm, phase II clinical trial of intraoperative radiotherapy using a low-energy X-ray source for local advanced Laryngocarcinoma (ILAL): A study protocol. BMC Cancer 202020, 734. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-020-07233-1 (2020).

Toita, T. et al. Intraoperative radiation therapy (IORT) for head and neck cancer. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 30, 1219–1224. https://doi.org/10.1016/0360-3016(94)90332-8 (1994).

Martínez-Monge, R. et al. IORT in the management of locally advanced or recurrent head and neck cancer. Front. Radiat. Ther. Oncol. 31, 122–125. https://doi.org/10.1159/000061179 (1997).

Schmitt, T. et al. IORT for locally advanced oropharyngeal carcinomas with major extension to the base of the tongue: 5-year results of a prospective study. Front. Radiat. Ther. Oncol. 31, 117–121. https://doi.org/10.1159/000061178 (1997).

Nilles-Schendera, A., Bruggmoser, G., Stoll, P., Frommhold, H. & Schilli, W. IORT in floor of the mouth cancer. Front. Radiat. Ther. Oncol. 31, 102–104. https://doi.org/10.1159/000061156 (1997).

Haller, J. R., Mountain, R. E., Schuller, D. E. & Nag, S. Mortality and morbidity with intraoperative radiotherapy for head and neck cancer. Am. J. Otolaryngol. 199617, 308–310. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0196-0709(96)90016-2 (1996).

Freeman, S. B. et al. Intraoperative radiotherapy of head and neck cancer. Arch. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 116, 165–168. https://doi.org/10.1001/archotol.1990.01870020041011 (1990).

Garrett, P., Pugh, N., Ross, D., Hamaker, R. & Singer, M. Intraoperative radiation therapy for advanced or recurrent head and neck cancer. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 13, 785–788. https://doi.org/10.1016/0360-3016(87)90300-2 (1987).

Herskind, C., Steil, V., Kraus-Tiefenbacher, U. & Wenz, F. Radiobiological aspects of intraoperative radiotherapy (IORT) with isotropic low-energy X rays for early-stage breast cancer. Radiat. Res. 163, 208–215. https://doi.org/10.1667/rr3292 (2005).

Brenner, D. J., Leu, C. S., Beatty, J. F. & Shefer, R. E. Clinical relative biological effectiveness of low-energy X-rays emitted by miniature X-ray devices. Phys. Med. Biol. 44, 323–333. https://doi.org/10.1088/0031-9155/44/2/002 (1999).

Wydmański, J. et al. A new method of targeted intraoperative radiotherapy using the orthovoltage photon radiosurgery system. Nowotw. J. Oncol. 55, 320. https://doi.org/10.5603/njo.53008 (2005).

Ang, K. K. et al. Randomized trial addressing risk features and time factors of surgery plus radiotherapy in advanced head-and-neck cancer. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 51, 571–578. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0360-3016(01)01690-x (2001).

Suwinski, R. et al. Time factor in postoperative radiotherapy: A multivariate locoregional control analysis in 868 patients. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 56, 399–412. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0360-3016(02)04469-3 (2003).

Lacas, B. et al. Meta-analysis of chemotherapy in head and neck cancer (MACH-NC): An update on 107 randomized trials and 19,805 patients, on behalf of MACH-NC Group. Radiother. Oncol. 156, 281–293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.radonc.2021.01.013 (2021).

Lacas, B. et al. Role of radiotherapy fractionation in head and neck cancers (MARCH): An updated meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 18, 1221–1237. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30458-8 (2017) (Erratum in: Lancet Oncol. 2018 Apr;19(4):e184).

Petit, C. et al. Chemotherapy and radiotherapy in locally advanced head and neck cancer: An individual patient data network meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 22, 727–736. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00076-0 (2021).

Herskind, C. & Wenz, F. Radiobiological comparison of hypofractionated accelerated partial-breast irradiation (APBI) and single-dose intraoperative radiotherapy (IORT) with 50-kV X-rays. Strahlenther. Onkol. 186, 444–451. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00066-010-2147-9 (2010).

Celejewska, A., Maciejewski, B., Wydmański, J. & Składowski, K. The efficacy of IORT (intraoperative radiotherapy) for early advanced breast cancer depending on the time delay of external beam irradiation (EXRT) post conservative breast surgery (CBS). Nowotw. J. Oncol. 71, 133–138. https://doi.org/10.5603/NJO.a2021.0019 (2021).

Blažek, T. et al. Dose escalation in advanced floor of the mouth cancer: A pilot study using a combination of IMRT and stereotactic boost. Radiat. Oncol. 16, 122. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13014-021-01842-1 (2021).

Yamazaki, H. et al. Hypofractionated stereotactic radiotherapy using CyberKnife as a boost treatment for head and neck cancer, a multi-institutional survey: Impact of planning target volume. Anticancer Res. 34, 5755–5759 (2014).

Hsieh, C. H. et al. Single-institute clinical experiences using whole-field simultaneous integrated boost (SIB) intensity-modulated radiotherapy (IMRT) and sequential IMRT in postoperative patients with oral cavity cancer (OCC). Cancer Control 27, 1073274820904702. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073274820904702 (2020).

Lapeyre, M. et al. Postoperative brachytherapy alone and combined postoperative radiotherapy and brachytherapy boost for squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity, with positive or close margins. Head Neck 26, 216–223. https://doi.org/10.1002/hed.10377 (2004).

Beitler, J. J. et al. Close or positive margins after surgical resection for the head and neck cancer patient: The addition of brachytherapy improves local control. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 40, 313–317. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0360-3016(97)00717-7 (1998).

Chen, A. M. et al. Recurrent salivary gland carcinomas treated by surgery with or without intraoperative radiation therapy. Head Neck 30, 2–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/hed.20651 (2008).

Fliekinger, J. C. & Niranjan, A. Stereotactic radiosurgery and radiotherapy. In Perez And Brady’s Principles and Parctice of Radiation Oncology 6th edn 351–361 (Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott, 2013).

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or no profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by G.W., T.R., W.M., A.N., T.L., Ż.K.-D., A.C., C.S., A.B. The main manuscript text was corrected by W.M., A.N., J.W., and B.M. The first draft of the manuscript was written by G.W., and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Maria Sklodowska-Curie National Research Institute of Oncology, Gliwice, Poland (protocol code KB/430-70/23). Also pilot group study protocol and consent to participate was accepted in 2003 by the Ethics Committee of Maria Sklodowska-Curie Institute of Oncology, Gliwice. All study subjects or their legal guardian(s) had given informed consent to participate in study and treatment.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Woźniak, G., Rutkowski, T., Majewski, W. et al. Long term effectiveness of intraoperative radiotherapy given as a boost in adjuvant treatment for oral cavity cancers. Sci Rep 15, 4786 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87498-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87498-3