Abstract

Enterococcus faecalis is responsible for numerous serious infections, and treatment options often include ampicillin combined with an aminoglycoside or dual beta-lactam therapy with ampicillin and a third-generation cephalosporin. The mechanism of dual beta-lactam therapy relies on the saturation of penicillin-binding proteins (PBPs). Ceftobiprole exhibits high affinity binding to nearly all E. faecalis PBPs, thus suggesting its potential utility in the treatment of severe E. faecalis infections. The availability of therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) for ampicillin and ceftobiprole has prompted the use of this drug combination in our hospital. Due to the time-dependent antimicrobial properties of these antibiotics, an infusion administration longer than indicated was chosen. From January to December 2020, twenty-one patients were admitted to our hospital for severe E. faecalis infections and were treated with this approach. We retrospectively analyzed their clinical characteristics and pharmacological data. Most patients achieved an aggressive PK/PD target (T > 4–8 minimum inhibitory concentration, MIC) when this alternative drug combination regimen was used. Our analysis included the study of E. faecalis biofilm production, as well as the kinetics of bacterial killing of ceftobiprole alone or in combination with ampicillin. Time-kill experiments revealed strong bactericidal activity of ceftobiprole alone at concentrations four times higher than the MIC for some enterococcal strains. In cases where a bactericidal effect of ceftobiprole alone was not evident, synergism with ampicillin and bactericidal activity were demonstrated instead. The prolonged infusion of ceftobiprole, either alone or with ampicillin, emerges as a valuable option for the treatment of severe invasive E. faecalis infections.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Enterococcus faecalis can cause a large variety of difficult-to-treat infections and monotherapy is generally non bactericidal. Life-threatening infections such as endocarditis and bacteremia might require combination therapy1. Synergism between amoxicillin and cefotaxime through partial saturation of penicillin-binding proteins (PBPs) 4 and 5 by amoxicillin and total saturation of PBPs 2 and 3 by cefotaxime is known2 and the combination of ampicillin and ceftriaxone was found to be safe and effective for treating IE3. with similar effectiveness compared to ampicillin plus gentamicin4, and lower rates of serious side-effects5. Ceftobiprole is a broad-spectrum cephalosporin with in vitro activity against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and E. faecalis6. Ceftobiprole and amoxicillin showed a synergistic and bactericidal effect against E. faecalis7. Owing to the pharmacodynamic characteristics of ceftobiprole, and the availability of therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) for both ampicillin and ceftobiprole at our institution, we have been increasingly using ampicillin plus ceftobiprole combination instead of ampicillin and ceftriaxone for the treatment of IE and other invasive infections caused by E. faecalis. A TDM-guided approach was used throughout the anti-infective pharmacologic treatment to adjust the doses of these two drugs and achieve the most aggressive antimicrobial PK/PD targets. The objective of this study is to delineate the pharmacological properties of ampicillin and ceftobiprole when used in combination to treat invasive E. faecalis infections, particularly IE. Our investigation concentrated on two main aspects: (1) attainment of PK/PD targets, (2) the antimicrobial efficacy of ceftobiprole both alone and in combination with ampicillin as demonstrated by time-kill assays. The findings are related to the clinical outcomes derived from our pharmacological evaluation strategy, as previously outlined in a case series published by our team8.

Materials and methods

Study design

This retrospective investigation encompassed adult patients treated for E. faecalis IE or bacteremia with the combination of ampicillin plus ceftobiprole between January 2020 to December 2020. The research took place at a tertiary university hospital, the Azienda Sanitaria Universitaria Friuli Centrale of Udine, Italy. The study was approved by the local Institutional Review Board and all research was performed in accordance with relevant guidelines/regulations. Due to the retrospective and observational nature of the analysis, the patient’s signed written informed consent was waived.

Ampicillin was administered via continuous intravenous infusion, starting with a standard dose of 16 g per day. The dosage was adjusted based on renal function: reduced to 12 g per day for an estimated creatinine clearance (eCLCR) between 30 mL/min and 50 mL/min, and further reduced to 8 g per day when eCLCR was < 30 mL/min. Ceftobiprole was initially administered utilizing the dosing regimens recommended for distinct classes of renal function. These dosages included 500 mg q8h over 3-h extended infusions (EI) for patients with eCLCR ≥50 mL/min, 500 mg q12h over 3 h-EI for those with eCLCR of 30–50 mL/min, and 250 mg q12h over 3 h-EI for those with eCLCR <30 mL/min. Following a minimum of two days of treatment initiation, patients underwent TDM of both drugs. The objective of the TDM was to make dose adjustments that align with the optimal PK/PD target, represented by a steady-state free plasma trough concentration (fCtrough) to MIC ratio of 4–8 for the entire dosing interval (corresponding to a 100%fT > 4-8xMIC)9. This target was devised to achieve both clinical and microbiological cures, while concurrently mitigating the risk of overexposure and associated adverse events. We extracted demographic and clinical data from the medical records of each patient, including age, gender, weight, height, type of infection, bacterial clinical isolate and corresponding MICs of ampicillin and ceftobiprole, serum creatinine, eCLCR (calculated using the Cockcroft-Gault equation), ampicillin and ceftobiprole daily dose, and any concurrent medications.

Drug sampling

A single blood sample was collected during continuous ampicillin infusion. Because of the 8-hourly intermittent 3-hour duration intravenous infusion of ceftobiprole, we usually performed three venous blood samples to characterize the PK profile of ceftobiprole: before dosing, at the end of the drug infusion, and four hours after dosing. The ceftobiprole dosing interval Area Under the concentration-time curve (AUC0 − t), the half-life (T1/2), the volume of distribution (Vss) and the clearance (CL) were estimated by non-compartmental model.

Drug analysis

A high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) with ultraviolet (UV) detection method was used to quantify ceftobiprole in plasma. In brief, one milliliter of plasma or 0.5 mL of sample was spiked with cefepime as an internal standard (IS) and then subjected to solid-phase extraction (SPE) before HPLC analysis. A reverse phase chromatography separation was performed using Shimadzu Nexera-i equipped with UV detector (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) and with an InfinityLab Poroshell 120 EC -C18 column (3.0 × 50 mm with 2.7-micron particle size) (Agilent, Santa Clara, United States). The mobile phase, consisting of a mixture of acetonitrile and 30 mM phosphate buffer (pH 3.15), was used in a gradient mode and detection was performed at a wavelength of 296 nm. The method was linear in the concentration range of 1.0–30.0 microg/mL in plasma. Only total plasma concentrations were measured for both ampicillin and ceftobiprole, whereas the free fraction was estimated. According to literature, we considered a 20% and a 16% of binding protein for ampicillin and ceftobiprole, respectively10,11.

Microbiological study

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing

E. faecalis ATCC 29,212 (vancomycin-susceptible, VSE) was used as control strain in this study. All strains were further analyzed for the in vitro antibacterial activity. Ceftobiprole was provided by Basilea Pharmaceutica International Ltd. (Basel, Switzerland); ceftaroline, linezolid and tigecycline by Pfizer Inc. (New York, NY, USA); daptomycin by Novartis (Basel, Switzerland). Penicillin, ampicillin, amoxicillin, imipenem, vancomycin, teicoplanin, gentamicin and streptomycin were purchased commercially (Sigma Chemical Co., ST. Louis, MO, USA). MICs were determined by broth microdilution and interpreted according to the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) clinical breakpoints12. In the absence of EUCAST clinical breakpoints, those of the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute were applied13.

Time-kill experiments

Ten E. faecalis strains were available for in vitro time-kill experiments. Ceftobiprole exposure was tested at concentrations of one time MIC (1X MIC), two times MIC (2X MIC), and four times MIC (4X MIC). Ceftobiprole and ampicillin antibiotic combinations were tested for four strains. The experiments were performed in duplicate in 20 ml tubes containing cation adjusted Mueller-Hinton broth (CA-MHB). (Difco, Detroit, MI) using a starting inoculum of 105 -106 CFU/mL with ceftobiprole (1 X MIC, 2X MIC and 4X MIC) alone or in combination with ampicillin at 1X MIC). Data points are averages from duplicate CFU/mL determination within an experiment. Bactericidal activity was defined as a ≥ 3 log10 decrease in bacterial count at 24 h. Synergy was measured at 24 h and was defined as a ≥ 2 log10 decrease in CFU/ml by the combination compared with its most active constituent and a ≥ 2 log10 decrease in the CFU/ml below the starting inocula14.

Biofilm production

The ability of E. faecalis isolates to form biofilms was estimated using the 96-microtiter plate method, as described previously with some minor modifications15. Briefly, 150 µl of the broth cultures in trypticase soy broth (TSB; Oxoid, Basingstoke, UK) with 0.25% glucose (OD600 ~ 0.4) were inoculated in the microplates and incubated at 37° C under agitation for 24 h. After that, the wells were washed 3 times with 0.9% w/v NaCl and the remaining attached bacteria heat-fixed by incubating the plate at 37 °C for 1 h. The adherent biofilms were stained with 150 µl of 0.4% crystal violet for 30 min at room temperature. The plates were washed at least 3 times and dried at 37° C for 1 h. The crystal violet was solubilized in 150 µL of 33% acetic acid and a microplate reader (GloMax® multidetection system) was used to read the optical density at a wavelength of 595 nm. Uninoculated blank wells containing tryptone soya broth (TSB; Oxoid, Basingstoke, UK) were used to determine background OD. The average from a triplicate OD value were calculated for all tested strains and negative controls. For the interpretation of the results, S. epidermidis ATCC 35,984 and E. faecalis ATCC 29,212 were used as positive (strong biofilm producer) and negative (no biofilm producer) controls, respectively. Based on the comparison between their OD values with those of the controls, strains were divided into the following categories: no biofilm producer (0), weak biofilm producer (+ or 1), moderate biofilm producer ( + + or 2) and strong biofilm producer (+++ or 3).

Statistical analysis

A descriptive statistical analysis was used to describe the characteristics of the treated population and measurements of plasma antimicrobial concentrations. For continuous variables, means, standard deviations, medians and interquartile ranges were calculated. For discrete variables, the frequency of distribution was presented. The normality of the distribution of continuous variables was tested by the Shapiro-Wilk test. The software used for data analysis was GraphPad Prism (version 10.1.1, November 2023).

Results

Patients

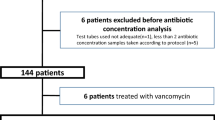

A total of 21 patients with E. faecalis invasive infections were admitted to our hospital from January 2020 to December 2020 as previously reported in Giuliano et al. where population is described8.

Pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic index determination

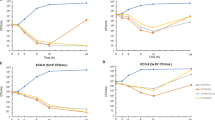

The descriptive analyses of ampicillin and ceftobiprole plasmatic concentrations are reported in Figs. 1 and 2; Tables 1 and 2.

Ceftobiprole (BPR) and ampicillin serum concentrations. efC BPR 50%T: estimated free serum concentration at 50% of the dosing interval; efC BPR 100%T: estimated free trough serum concentration of ceftobiprole; ef Css ampicillin: estimated free serum concentration of ampicillin at the steady state during a continuous infusion. The y-axis is represented on a log2 scale.

The MIC50 and the MIC90 of the isolated E. faecalis strains for ceftobiprole was 0.5 mg/L and 1 mg/L, respectively. The MIC50 and the MIC90 of the isolated E. faecalis strains for ampicillin was 1 mg/L and 2 mg/L, respectively. We calculated the PK/PD index for both ceftobiprole and ampicillin (Fig. 3). We found that the free serum concentrations of ceftobiprole were 18-fold the MIC (median 17.9; IQR 5.8–27.2)], whereas the free serum concentrations of ampicillin were 46-fold the MIC (median 46.1; IQR 29.7–77.0). The coefficient of variation of the PK/PD index of ceftobiprole and ampicillin were 70.5% and 67.9%, respectively. For both antimicrobials, at least 80% of patients achieved the PK/PD target of 100% T > MIC, and at least 60% the optimal ones represented by 100% T > 4MIC, as detailed in Table 2. A descriptive overview of clinical, microbiological, and pharmacological data of each case is reported in Table 3.

Ceftobiprole (BPR) and ampicillin PK/PD index. The observed Pharmacokinetic/Pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) ratios at 100% of dosing interval (100% fT > MIC). A ratio of 1 represents the minimum PK/PD therapeutic target, whereas the ratio of 4 (dotted red line) represents a high antimicrobial activity. The reported MICs derive from pathogen isolates or surrogates from EUCAST when unknown. The PK/PD index was calculated referring to estimated free serum concentrations of antibiotics. The y-axis is represented on a log2 scale. Legend. MIC - minimum inhibitory concentration; EUCAST - European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing.

In vitro susceptibility testing and time-kill experiments

Ten E. faecalis strains were available for time-kill experiments and biofilm production assessment. In two of these isolates (see Fig. 4and Supplementary Fig. 1), which were no-biofilm producers with a ceftobiprole MIC of 0.25 mg/L, ceftobiprole exhibited bactericidal activity at 8 and 24 h after exposure to drug concentrations four times the MIC. In another isolate of E. faecalis, characterized by weak biofilm production and a ceftobiprole MIC of 0.5 mg/L, bactericidal activity was observed at 8 and 24 h after exposure to drug concentrations four times the MIC (Fig. 5). In an additional isolate with a ceftobiprole MIC of 1 mg/L and moderate biofilm production, bactericidal activity of ceftobiprole alone was observed at four times the MIC at 4-, 8-, and 24-hours post-exposure to the drug (see Supplementary Fig. 2). For another E. faecalis strain with a ceftobiprole MIC of 0.25 mg/L and for which a very high level of biofilm production was recognized (+++), ceftobiprole was bactericidal alone at two and four times the MIC at 24-hours post-exposure; addition of ampicillin at concentration equal to its MIC did not result in synergism (Fig. 6). In Fig. 7, the time-kill experiment of an E. faecalis isolate with moderate biofilm production and a ceftobiprole MIC of 0.5 mg/L is illustrated. Ceftobiprole did not exhibit a bactericidal effect at concentrations of 1, 2, and 4 times the MIC, even after 24-hour incubation, for this strain. Additionally, the isolate showed regrowth after 8 h of drug exposure. Furthermore, the antibiotic gradient diffusion strip conducted on this strain revealed an MIC of 0.75 mg/L (Fig. 8A). Colonies displaying heteroresistance were observed within the inhibition zone, and the antibiotic gradient diffusion strip performed on these internal colonies of heteroresistance showed an MIC of 16 mg/L (Fig. 8B). When this isolate was exposed to ceftobiprole at 1X MIC, 2X MIC, and 4X MIC, along with ampicillin at a concentration equal to its MIC, a synergistic effect was observed at 8- and 24-hours post-exposure to the drugs (Fig. 9). The same pattern was observed for another E. faecalis strain, which was a strong producer of biofilm in vitro. Ceftobiprole exhibited weak activity alone; however, when combined with ampicillin at a concentration equal to its MIC, a synergistic killing effect was demonstrated (see Supplementary Fig. 3).

Discussion

One of the most significant features that distinguishes Enterococcus from Streptococcus is its tolerance to penicillin, defined as an MBC to MIC ratio greater than 3216. Tolerance to beta-lactams justifies the need to use a combination of drugs to achieve bactericidal effect, as no antibacterial agent has proven to be bactericidal on its own against Enterococcus spp., so far16. Penicillin alone is bactericidal against Enterococcus only at high doses17; however, when combined with streptomycin, a bactericidal effect is achieved at lower penicillin doses17. The successful mechanism of the penicillin and aminoglycoside combination is based on the destruction of peptidoglycan by penicillin, leading to aminoglycoside accumulation inside the cell18. In this context, aminopenicillins are even more effective, being four times more active against susceptible Enterococcus cells than penicillin19. Since the second decade of the 2000s, a new treatment regimen for severe E. faecalis infections has emerged4. This regimen includes the combination of two beta-lactams, ampicillin and ceftriaxone4. This dual beta-lactam regimen has been demonstrated to be non-inferior to the combination of ampicillin and gentamicin. No significant differences in mortality during antimicrobial treatment were observed between the ampicillin-ceftriaxone combination and the ampicillin-gentamicin combination (22% vs. 21%, P = .81). Similarly, comparable outcomes were noted for mortality at the 3-month follow-up (8% vs. 7%, P = .72), treatment failure (1% vs. 2%, P = .54), and relapse rates (3% vs. 4%, P = .67)4. Moreover, due to a lower prevalence of nephrotoxicity (OR 0.45 [0.26–0.77], P = .0182) and drug withdrawal caused by adverse effects (OR 0.11 [0.03–0.46], P = .0160), dual beta-lactam therapy may be a preferable option compared to ampicillin plus aminoglycoside, as demonstrated by Mirna and colleagues20. The importance of combination therapy for infective endocarditis caused by E. faecalis has recently been further emphasized by Danneels and colleagues21. They highlighted that the recurrence rate of enterococcal infective endocarditis was significantly higher in patients receiving monotherapy with ampicillin compared to combination therapy with ampicillin plus gentamicin or the sequential treatment of ampicillin and gentamicin followed by ampicillin and ceftriaxone21. The mechanism of dual beta-lactam combination therapy in E. faecalis might be explained by the concept of the critical level of PBP binding. PBPs are proteins involved in the building of peptidoglycan chains and are distinguished into three classes according to their enzymatic activity: (1) class A, dual-functional PBPs with both glycosyltransferase and transpeptidase activities; (2) class B, transpeptidases; and (3) class C, carboxypeptidases and endopeptidases22. Enterococci have three class A and three class B PBPs23,24. Several class B PBPs, specifically PBP4 and PBP5, are involved in reduced beta-lactam susceptibility in E. faecalis and E. faecium, respectively22. In the case of ampicillin and ceftriaxone combination, ampicillin partially saturates essential PBP4 and PBP5, resulting in the upregulation of non-essential PBP2 and PBP3, to which ceftriaxone subsequently binds, achieving total PBP saturation2,25,26. Fontana and coworkers27 highlighted three interesting points about the role of PBPs as the killing target of beta-lactams in E. faecalis. First, a direct relationship was demonstrated between bacterial growth rate and penicillin sensitivity: the higher the growth rate the lower the penicillin MIC was27. Secondly, in conditions of optimal E. faecalis growth, PBP3 was found to be the only lethal target of penicillin: a certain amount of PBP3 saturation was necessary for lethality27. Lastly, a reduced level of PBP3 saturation was found in conditions of suboptimal growth; however, even when the saturation of PBP3 by penicillin obtained in conditions of non-optimal growth (i.e. in a situation in which a higher dose of antibiotic is required for inhibition because of reduced susceptibility) was the same of that realized in condition of optimal growth, still PBP3 alone could not be identified as the sole lethal target27. All these findings demonstrate that inhibition by beta-lactams is indirect and non-constant, depending on which PBP is essential for growth in a certain physiologic status and on its affinity for the antibiotic28. Whatever the crucial PBPs are for each growth condition, a “critical” level of PBP binding is required for cell killing. This “critical” level might be a composite of beta-lactam affinity to the PBPs and number of PBPs bound. Hence beta-lactam and, at a greater extent, beta-lactam combinations, by binding to different PBP with various levels of affinity, can increase PBP saturation to the critical level necessary for bacterial killing. Unlike ceftriaxone or cefotaxime, ceftobiprole exhibits intrinsic activity against E. faecalis, which is linked to its high affinity for almost all enterococcal PBPs. By strongly binding to PBP1, PBP2, and PBP3, and saturating PBP4 and PBP5 as well29, ceftobiprole might be able to achieve the “critical” level of PBP binding required to eliminate E. faecalis. In addition, while mutations causing overexpression of pbp4 may be associated with increased MICs of ceftriaxone and reduced effectiveness of the combination of ceftriaxone and ampicillin30, the bactericidal activity of ceftobiprole is not significantly influenced by increased pbp4 gene expression or point mutations causing alterations in the catalytic site motif of PBP431. These results indicate the need to explore alternative antibiotic combinations for treating different contemporary isolates of E. faecalis causing IE30, and one potential combination to consider might be ampicillin plus ceftobiprole. Other potential options for treating severe E. faecalis infections include combinations such as ceftobiprole with daptomycin, gentamicin, or levofloxacin, which have shown synergistic effects in certain time-kill studies32,33,34.

From a pharmacokinetic perspective, the results of this study demonstrate that intravenous infusion of ceftobiprole and ampicillin, tailored to optimize the time-dependent properties of both drugs by the extension of the time of administration, achieved plasma concentrations that were well above the MICs. Given the innovative administration method for ceftobiprole and ampicillin, performing TDM ensured adequate exposure to the antibacterial therapy, enabling the attainment and maintenance of concentrations suitable for achieving aggressive PK/PD targets compared to intermittent infusion. Considering the potential synergistic effect of ampicillin and ceftobiprole, we speculate that the possible resulting reduction in MICs could lead to a higher PK/PD target attainment rate than those observed in this study. This might yield two key benefits: enhanced clinical and microbiological efficacy, and a possible reduction in the required drug dosage, offering advantages in terms of both safety and Pharmacoeconomics. It is worth noting that our high value of the PK/PD indices for both ceftobiprole and ampicillin were mainly derived from the low MIC values reported for the isolated pathogens, rather than the high antimicrobial serum concentrations. Nevertheless, our data show that the use of prolonged infusion administration of ampicillin and ceftobiprole is associated with high serum concentrations, despite the initial dose being adjusted based on baseline renal function to minimize antibiotic overexposure and reduce the risk of toxicity. This may also suggest the use of a TDM-based approach to accordingly modify the dosing of antimicrobial therapy9. Among some E. faecalis isolates, ceftobiprole exhibited bactericidal activity at multiple time points post-exposure at various multiples of the MIC, regardless biofilm production ability of the strain. Overall, even in isolates strongly producing biofilm, a synergistic effect with ampicillin was not demonstrable when ceftobiprole exhibited high bactericidal activity by itself at concentrations two or four times the MIC. However, the consistent demonstration of the bactericidal effect of ceftobiprole alone was not observed across all isolates, particularly among those which were biofilm producers (see Fig. 7and Supplementary Fig. 3). Moreover, these isolates showed regrowth after 8 h of drug exposure and for one of them ceftobiprole heteroresistance was observed. We hypothesized that three strain-specific mechanisms underlie the loss of ceftobiprole bactericidal activity: resistance and heteroresistance, biofilm-forming capacity, and quorum sensing system. Non-susceptibility to ceftobiprole in E. faecalis primarily arises from the overexpression of pbp4, driven by mutations in the promoter region, and alterations in the catalytic site motifs of PBP4 which might have the potential to interfere with the formation of the ceftobiprole/PBP4 complex31. Antimicrobial non-susceptibility is linked to a fitness cost, resulting in a trade-off scenario: in the presence of antibiotics, resistant strains outcompete susceptible bacteria, while in antibiotic-free environments, they are disadvantaged compared to susceptible strains35. Heteroresistance, characterized by a lower fitness cost than full resistance, is thus a more favorable phenotype; furthermore, it is unstable and reversible36. In biofilms, bacteria act collectively, resembling a multicellular organism, to respond to various environmental conditions37. This phenomenon is known as quorum sensing system37,38,39. In the biofilm context, under antibiotic pressure, subpopulations of resistant and heteroresistant bacteria gain a selective advantage over antibiotic-susceptible populations. Resistance and heteroresistance phenotypes are regulated by quorum sensing through the production of autoinducers40,41,42,43,44. This sacred triangle, comprising biofilm formation, quorum sensing, and the development of resistance and, particularly, heteroresistance, due to its advantage over full resistance, could elucidate the behavior of some of our biofilm-forming E. faecalis isolates, wherein ceftobiprole alone did not exhibit bactericidal activity. In Pseudomonas aeruginosa, ceftazidime binds mainly to PBP1a and PBP345, quenching quorum sensing system and preventing the expression of specific quorum-sensing-related virulence phenotypes46. Furthermore, in P. aeruginosa synergism between beta-lactams against biofilm that is potentially related to inhibition of multiple PBP targets has already been hypothesized47. Similarly, we could hypothesize that ampicillin and ceftobiprole combination, by binding enterococcal PBPs at a critical level necessary to inhibit the quorum sensing system, might revert heteroresistance, disrupt biofilm, and lead to a synergistic effect that kills enterococci. Our study has several limitations that may affect the generalizability of our findings. These include the retrospective and monocentric nature of our analysis, the limited sample size, and the absence of a treatment control group. Additionally, only total drug concentrations were measured, with the free fractions of ampicillin and ceftobiprole being estimated.

Conclusions

Our study suggests the potential of ceftobiprole alone or in combination with ampicillin as a promising treatment option for severe E. faecalis infections, particularly IE. Through pharmacological characterization and antibacterial activity assessments, we have highlighted the potential efficacy of this combination therapy, which may offer advantages over traditional antibiotic regimens. By building upon previous clinical discussions and recognizing the urgency in finding alternative treatments amidst emerging resistance patterns, our findings offer a significant contribution towards identifying more effective treatment regimens for managing E. faecalis infections. Moving forward, further research, including larger prospective studies, is warranted to fully elucidate the potential benefits and optimize the use of ceftobiprole and ampicillin combination therapy in clinical practice. Overall, our study might represent an important advancement in the field of antimicrobial therapy and has the potential to improve outcomes for patients with IE due to E. faecalis.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon request.

References

Megran, D. W. Enterococcal endocarditis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 15, 63–71. https://doi.org/10.1093/clinids/15.1.63 (1992).

Mainardi, J. L., Gutmann, L., Acar, J. F. & Goldstein, F. W. Synergistic effect of Amoxicillin and cefotaxime against Enterococcus faecalis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 39, 1984–1987. https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.39.9.1984 (1995).

Gavaldà, J. Brief communication: Treatment of Enterococcus faecalis Endocarditis with Ampicillin plus Ceftriaxone. Ann. Intern. Med. 146, 574. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-146-8-200704170-00008 (2007).

Fernández-Hidalgo, N. et al. Ampicillin Plus Ceftriaxone is as effective as Ampicillin Plus Gentamicin for treating Enterococcus faecalis infective endocarditis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 56, 1261–1268. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/cit052 (2013).

Lebeaux, D., Fernández-Hidalgo, N., Pilmis, B., Tattevin, P. & Mainardi, J-L. Aminoglycosides for infective endocarditis: Time to say goodbye? Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 26, 723–728. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmi.2019.10.017 (2020).

Arias, C. A., Singh, K. V., Panesso, D. & Murray, B. E. Evaluation of ceftobiprole medocaril against Enterococcus faecalis in a mouse peritonitis model. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 60, 594–598. https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dkm237 (2007).

Peiffer-Smadja, N. et al. In vitro bactericidal activity of Amoxicillin combined with different cephalosporins against endocarditis-associated Enterococcus faecalis clinical isolates. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 74, 3511–3514. https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dkz388 (2019).

Giuliano, S. et al. Ampicillin and Ceftobiprole Combination for the treatment of Enterococcus faecalis invasive infections: The Times they are A-Changin. Antibiotics (Basel). 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics12050879 (2023).

Cojutti, P. G. et al. Population Pharmacokinetic and Pharmacodynamic Analysis for maximizing the effectiveness of Ceftobiprole in the treatment of severe methicillin-resistant staphylococcal infections. Microorganisms 11, 2964. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms11122964 (2023).

Barza, M. & Weinstein, L. Pharmacokinetics of the penicillins in man. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 1, 297–308. https://doi.org/10.2165/00003088-197601040-00004 (1976).

Torres, A., Mouton, J. W. & Pea, F. Pharmacokinetics and dosing of Ceftobiprole Medocaril for the treatment of hospital- and community-acquired pneumonia in different patient populations. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 55, 1507–1520. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40262-016-0418-z (2016).

The European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Breakpoint tables for interpretation of MICs and zone diameters. Version 13.1 2023. http://www.eucast.org (2023)

CLSI. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing 33rd ed. CLSI Supplement M100 (Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, 2023).

NCCLS. Methods for Determining Bactericidal Activity of Antimicrobial Agents. Approved Guideline. NCCLS document M26-A [ISBN 1-56238-384-1]. NCCLS 940 West Valley Road, Suite 1400, Wayne, Pennsylvania 19087 USA (1999).

Stepanović, S. et al. Quantification of biofilm in microtiter plates: Overview of testing conditions and practical recommendations for assessment of biofilm production by staphylococci. APMIS 115, 891–899. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0463.2007.apm_630.x (2007).

Krogstad, D. J. & Pargwette, A. R. Defective killing of enterococci: A common property of antimicrobial agents acting on the cell wall. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 17, 965–968. https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.17.6.965 (1980).

Jawetz, E. & Sonne, M. Penicillin-streptomycin treatment of Enterococcal Endocarditis. N. Engl. J. Med. 274, 710–715. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM196603312741304 (1966).

Moellering, R. C. & Weinberg, A. N. Studies on antibiotic synergism against enterococci. J. Clin. Invest. 50, 2580–2584. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI106758 (1971).

Meer, J. T. M. et al. Distribution, antibiotic susceptibility and tolerance of bacterial isolates in culture-positive cases of endocarditis in the Netherlands. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 10, 728–734. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01972497 (1991).

Mirna, M., Topf, A., Schmutzler, L., Hoppe, U. C. & Lichtenauer, M. Time to abandon ampicillin plus gentamicin in favour of ampicillin plus ceftriaxone in Enterococcus faecalis infective endocarditis? A meta-analysis of comparative trials. Clin. Res. Cardiol. 111, 1077–1086. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00392-021-01971-3 (2022).

Danneels, P. et al. Impact of Enterococcus faecalis Endocarditis Treatment on Risk of Relapse. Clin. Infect. Dis. 76, 281–290. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciac777 (2023).

Moon, T. M. et al. The structures of penicillin-binding protein 4 (PBP4) and PBP5 from Enterococci provide structural insights into β-lactam resistance. J. Biol. Chem. 293, 18574–18584. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.RA118.006052 (2018).

Arbeloa, A. et al. Role of class A penicillin-binding proteins in PBP5-Mediated β-Lactam Resistance in Enterococcus faecalis. J. Bacteriol. 186, 1221–1228. https://doi.org/10.1128/JB.186.5.1221-1228.2004 (2004).

Sauvage, E., Kerff, F., Terrak, M., Ayala, J. A. & Charlier, P. The penicillin-binding proteins: Structure and role in peptidoglycan biosynthesis. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 32, 234–258. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-6976.2008.00105.x (2008).

D’Arezzo, S. et al. Ceftaroline Plus Ampicillin against Gram-positive organisms: results from E-Test synergy assays. Microb. Drug Resist. 23, 507–515. https://doi.org/10.1089/mdr.2016.0030 (2017).

Gavalda, J. Efficacy of ampicillin combined with ceftriaxone and gentamicin in the treatment of experimental endocarditis due to Enterococcus faecalis with no high-level resistance to aminoglycosides. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 52, 514–517. https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dkg360 (2003).

Fontana, R., Canepari, P., Satta, G. & Coyette, J. Identification of the lethal target of benzylpenicillin in Streptococcus faecalis by in vivo penicillin binding studies. Nature 287, 70–72. https://doi.org/10.1038/287070a0 (1980).

Canepari, P., Lleo, M. D. M., Cornaglia, G., Fontana, R. & Satta, G. In Streptococcus faecium penicillin-binding protein 5 alone is sufficient for growth at Sub-maximal but not at maximal rate. Microbiology (N Y). 132, 625–631. https://doi.org/10.1099/00221287-132-3-625 (1986).

Henry, X., Amoroso, A., Coyette, J. & Joris, B. Interaction of ceftobiprole with the low-affinity PBP 5 of Enterococcus faecium. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54, 953–955. https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.00983-09 (2010).

Westbrook, K. J. et al. Differential in vitro susceptibility to ampicillin/ceftriaxone combination therapy among Enterococcus faecalis infective endocarditis clinical isolates. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dkae032 (2024).

Lazzaro, L. M., Cassisi, M., Stefani, S. & Campanile, F. Impact of PBP4 alterations on β-Lactam Resistance and Ceftobiprole Non-susceptibility among Enterococcus faecalis clinical isolates. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2021.816657 (2022).

Werth, B. J. et al. Ceftobiprole and ampicillin increase daptomycin susceptibility of daptomycin-susceptible and -resistant VRE. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 70, 489–493. https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dku386 (2015).

Arias, C. A., Singh, K. V., Panesso, D. & Murray, B. E. Time-kill and synergism studies of ceftobiprole against Enterococcus faecalis, including beta-lactamase-producing and Vancomycin-resistant isolates. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51, 2043–2047. https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.00131-07 (2007).

Campanile, F., Bongiorno, D., Mongelli, G., Zanghì, G. & Stefani, S. Bactericidal activity of ceftobiprole combined with different antibiotics against selected Gram-positive isolates. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 93, 77–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2018.07.015 (2019).

Rajer, F. & Sandegren, L. The role of antibiotic resistance genes in the fitness cost of multiresistance plasmids. MBio 13, e0355221. https://doi.org/10.1128/mbio.03552-21 (2022).

Levin, B. R. et al. Theoretical Considerations and Empirical Predictions of the Pharmaco- and Population Dynamics of Heteroresistance. BioRxiv. (2023). https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.09.21.558832

Vendeville, A., Winzer, K., Heurlier, K., Tang, C. M. & Hardie, K. R. Making sense of metabolism: Autoinducer-2, LUXS and pathogenic bacteria. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 3, 383–396. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro1146 (2005).

Cámara, M., Williams, P. & Hardman, A. Controlling infection by tuning in and turning down the volume of bacterial small-talk. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2, 667–676. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(02)00447-4 (2002).

Swift, S. et al. Quorum sensing as a population-density-dependent determinant of bacterial physiology, pp. 199–270 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2911(01)45005-3

Naga, N. G., El-Badan, D. E., Ghanem, K. M. & Shaaban, M. I. It is the time for quorum sensing inhibition as alternative strategy of antimicrobial therapy. Cell. Commun. Signal. 21, 133. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12964-023-01154-9 (2023).

Sionov, R. V. & Steinberg, D. Targeting the holy triangle of quorum sensing, biofilm formation, and antibiotic resistance in pathogenic bacteria. Microorganisms. 10 (2022). https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms10061239

Lu, Y. et al. Quorum sensing regulates heteroresistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Front. Microbiol. 13 (2022). https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2022.1017707.

Lopes, S. P., Jorge, P., Sousa, A. M. & Pereira, M. O. Discerning the role of polymicrobial biofilms in the ascent, prevalence, and extent of heteroresistance in clinical practice. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 47, 162–191. https://doi.org/10.1080/1040841X.2020.1863329 (2021).

Zhao, X., Yu, Z. & Ding, T. Quorum-sensing regulation of Antimicrobial Resistance in Bacteria. Microorganisms 8, 425. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms8030425 (2020).

Moyá, B., Zamorano, L., Juan, C., Ge, Y. & Oliver, A. Affinity of the new cephalosporin CXA-101 to penicillin-binding proteins of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54, 3933–3937. https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.00296-10 (2010).

Skindersoe, M. E. et al. Effects of antibiotics on quorum sensing in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52, 3648–3663. https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.01230-07 (2008).

Tascini, C. et al. Infective Endocarditis Associated with Implantable Cardiac device by Metallo-β-Lactamase-Producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa, successfully treated with Source Control and Cefiderocol Plus Imipenem. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 67, e0131322. https://doi.org/10.1128/aac.01313-22 (2023).

Funding

The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conception and design of the study, SG, JA, CT; acquisition of data, LM, DD; analysis and interpretation of data, SG, JA, FC, PC, SF, AP, FS, MHA-Z; drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content, SG, JA, FC, MOC, JAR, RB, CT.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board, Department of Medicine, University of Udine. Prot IRB: 111/2024.

Consent to participate

Due to the retrospective and observational nature of the analysis, patient’s signed written informed consent was waived.

Consent to publish

Due to the retrospective and observational nature of the analysis, patient’s signed written informed consent to publish was waived.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Giuliano, S., Angelini, J., Campanile, F. et al. Evaluation of ampicillin plus ceftobiprole combination therapy in treating Enterococcus faecalis infective endocarditis and bloodstream infection. Sci Rep 15, 3519 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87512-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87512-8