Abstract

Various modelling techniques are available to understand the temporal and spatial variations of the phenology of species. Scientists often rely on correlative models, which establish a statistical relationship between a response variable (such as species abundance or presence-absence) and a set of predominantly abiotic covariates. The choice of the modeling approach, i.e., the algorithm, is itself a significant source of variability, as different algorithms applied to the same dataset can yield disparate outcomes. This inter-model variability has led to the adoption of ensemble modelling techniques, among which stacked generalisation, which has recently demonstrated its capacity to produce robust results. Stacked ensemble modelling incorporates predictions from multiple base learners or models as inputs for a meta-learner. The meta-learner, in turn, assimilates these predictions and generates a final prediction by combining the information from all the base learners. In our study, we utilized a recently published dataset documenting egg abundance observations of Aedes albopictus collected using ovitraps. and a set of environmental predictors to forecast the weekly median number of mosquito eggs using a stacked machine learning model. This approach enabled us to (i) unearth the seasonal egg-laying dynamics of Ae. albopictus for 12 years; (ii) generate spatio-temporal explicit forecasts of mosquito egg abundance in regions not covered by conventional monitoring initiatives. Our work establishes a robust methodological foundation for forecasting the spatio-temporal abundance of Ae. albopictus, offering a flexible framework that can be tailored to meet specific public health needs related to this species.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Understanding the phenology of species — the study of periodic events in biological life cycles shaped by seasonal and annual climate fluctuations — is essential across fields like agriculture (e.g., crop yield forecasting1), nature conservation (e.g., assessing species responses to global changes2), and public health (e.g., managing allergens and emerging infectious diseases carried by arthropod vectors3). Ecologists have therefore developed and tested several modelling approaches, i.e. the mechanistic and correlative approaches, to infer the phenology of species and how it varies over space and time. The mechanistic approach employs laboratory or field observations about the influence of biotic or abiotic factors on the targeted life history traits (e.g. the effect of temperature on a juvenile form development rate) to parametrise mathematical models inferring the life cycle of the species of interest (e.g4,5,6,7). Although generally accurate, mechanistic models often require estimating multiple parameters and are therefore constrained by the availability of ecological observations in the scientific literature7,8. As an alternative, ecologists frequently turn to correlative models, which establish statistical relationships between a response variable (e.g., species abundance or presence-absence) and a set of mostly abiotic covariates9,10.

Despite the utility of correlative models, their outputs are subject to various sources of variability, such as sampling location bias and model tuning11,12,13,14. The choice of the modelling method, in addition, has proven influential, as different models applied to the same dataset can yield distinct results15,16,17. This inter-model variability has prompted the use of ensemble modelling techniques, also called consensus modelling, which involves fitting multiple independent algorithms on the same input data and then aggregating the individual models’ outputs to produce a final prediction, reducing the risk of overfitting and extrapolation issues17. While simple aggregation methods like averages and weighted averages have been traditionally used17,18, more advanced ensemble techniques, such as stacking or stacked generalisation19, have recently demonstrated superior performance20,21,22,23. In stacked ensemble modelling, multiple base models’ predictions serve as inputs for a meta-learner, which learns from these predictions and generates the ultimate prediction by combining information from all the base models.

Leveraging the strengths of spatio-temporal stacked modeling in capturing complex dynamic ecological processes, we applied this approach to infer the weekly egg abundance of the invasive mosquito Aedes albopictus in Southern Europe from 2010 to 2022. The ‘Asian tiger mosquito’ (Aedes (Stegomyia) albopictus), with its rapid expansion24,25 and critical role as a vector for outbreaks of vector-borne diseases26,27,28,29, presents a compelling case study for evaluating the model’s capability to accurately forecast spatio-temporal patterns of egg-laying activity and abundance, enabling targeted public health interventions.

Local public health authorities have established surveillance and monitoring initiatives to better understand the distribution, abundance, and seasonality of Ae. albopictus, supporting the development of proactive strategies for population and disease control. However, these efforts require significant economic and personnel resources. As a result, the implementation of passive surveillance systems — such as modeling techniques that reliably predict vector abundance and seasonal patterns — has been advocated to provide invaluable support to local public health agencies30. Although correlative models are commonly used to infer the geographic distribution of Ae. albopictus31, this study is, to our knowledge, the first to apply a stacked spatio-temporal model for this species, generating weekly maps of egg abundance that highlight the length and peak of the oviposition activity. The model enables the inference of seasonal egg abundance even in areas lacking active surveillance, providing crucial support for resource allocation in monitoring and surveillance efforts. These results lay a robust methodological foundation for forecasting the spatio-temporal abundance of Ae. albopictus and offer a flexible framework adaptable to specific public health needs associated with this species.

Methods

Biological observations and area of interest

We used Ae. albopictus’ egg counts obtained from monitoring activities conducted with ovitraps as the response variable in our models. Ovitraps are cheap and efficient monitoring tools consisting of a dark container filled with water and a substrate, usually a masonite stick, where container-breeding mosquitoes can lay their eggs. The egg-laying substrate is collected on a weekly or biweekly basis, depending on the local protocol adopted by the stakeholders, and the number of eggs laid on the egg-laying substrate counted.

We used the VectAbundance v0.15 database, which contains ovitrap observations from four European countries (Albania, France, Italy, and Switzerland) with active monitoring and surveillance programs for Ae. albopictus between 2010 and 202232. In VectAbundance, individual ovitrap observations were processed such that, if the monitoring period exceeded one week, egg counts were randomly distributed across the active weeks. Additionally, to account for microclimatic variability and sampling differences, the data were aggregated using the median within a 9 × 9 km grid (see Da Re et al.32 for a detailed description of the sampling protocols and data preprocessing).

The observations available in VectAbundance v0.15 are located in a geographical extent spanning from 6° to 21° E and from 36° to 47° N (Fig. 1). According to Cervellini et al.33, this area is characterised by three main biogeographical regions, namely Alpine, Continental, and Mediterranean (Fig. 1). Since the location of the ovitraps well represents these three biogeographical regions, we decided to limit the geographical area of extrapolation of the model to the abovementioned geographical extent and these biogeographical regions only.

Biogeographical regions of Europe according to Cervellini et al.33 and the location (green dots) of the egg observations available in VectAbundance v0.15. The black lines represent the borders of the administrative areas of the countries of interest at the NUTS2 level. The map was created using R v4.334.

Modelling

Stacked generalisation is a technique that combines predictions from multiple individual models, known as base learners or base models, to make a final prediction19,20,23,35. In stacked generalisation, the outputs of individual base learners serve as inputs to a meta-learner, which is another model that learns from the predictions of the individual models. The meta-learner then generates the final prediction by combining and synthesising the information from the individual models (Fig. 2a). Stacking has the potential to improve the accuracy and robustness of ecological models by leveraging the strengths of different models and effectively capturing complex relationships in the data20. However, it is important to remark that while stacking can reduce model variance and improve predictions, it comes with trade-offs as it increases model complexity, reduces interpretability, and augments the computational time compared to individual models36.

Model formulation

As with all correlative models, stacked models require providing each base learner with a response variable and a set of covariates. We used as a response variable the weekly egg observations described in Sect. 2.1. As covariates, we selected three main environmental drivers that significantly influence the behaviour and development of mosquitoes, namely temperature, photoperiod (i.e., duration of daylight in 24 h) and precipitation37,38,39,40,41,42,43. Covariate preprocessing, including details on each variable’s ecological significance and specific preprocessing steps, is described in SM1.1 and omitted here for brevity. For each of these three covariates, we considered also their lagged values, since the mosquito life cycle can take several days or weeks to complete38,40. The lagged temperatures and photoperiod were calculated as the median value between the observations recorded in the current week (t), the previous week (t-1), and the week before that (t-2), whilst the lagged precipitation was computed as the cumulative weekly value between the precipitation recorded in the current week (t), the previous week (t-1), and the week before that (t-2). We similarly processed these covariates also for lag t-3.

In addition to the environmental covariates, which we include as distributed lags, we considered seasonal and cyclical components. Specifically, we used the Fourier series, with sine and cosine harmonic waves, to accommodate the yearly pattern and shorter-term seasonality. For these calendar effects the Fourier terms offer a more parsimonious representation than dummy variables, in particular when the frequency of the data is large (see Hyndman and Athanasopoulos44, Ch. 7 Sect. 4). We selected four relevant harmonic: one pair of harmonics is used for describing the yearly evolution, whereas another pair of harmonics is needed to capture some seasonal patterns. The four trigonometric waves were added to the other environmental predictors and provided a significant contribution to describing the cyclic patterns and fluctuations in the median weekly number of eggs.

Based on the results of the explorative modelling (SM1.2), which suggested excluding lag-1 variables, and preliminary collinearity analysis (SM1.3), we designed two distinct but complementary models. The regression model infers the number of eggs as a function of temperature, photoperiod, and precipitation, all lagged by -2 and − 3 weeks, and the four Fourier’s harmonics (Eq. 1).

The autoregressive model (Eq. 2) adds to the predictors considered in the Regression model (Eq. 1) an autoregressive component based on the number of eggs observed at week t-1 (Egg count.lag1).

Stacked model

Each model formulation was applied to four individual base algorithms, namely extreme gradient boosting (xgBoost), boosted regression trees (BRT), random forest (RF) and cubist (Fig. 2b).

Extreme gradient boosting (xgBoost) is a powerful gradient boosting algorithm based on the concept of boosting, where weak models (typically decision trees) are sequentially trained to correct the mistakes made by the previous models45. The algorithm optimises an objective function by iteratively adding models to the ensemble, minimising the loss. xgBoost employs a gradient-based approach to improve the performance of the weak models and handle complex interactions among variables. Boosted regression trees (BRT) is a boosting algorithm that combines multiple decision trees to form an ensemble model46. Similar to xgBoost, BRT sequentially trains decision trees, with each subsequent tree focusing on correcting the errors made by the previous trees. The algorithm optimises an objective function by iteratively adding trees, and the final prediction is a weighted sum of the predictions from all the trees. Random Forest is an ensemble learning method that constructs a collection of decision trees and combines their predictions to make accurate predictions47. Each tree in the RF is built on a randomly sampled subset of the data and a randomly selected subset of features. This randomness helps to reduce overfitting and increase the diversity among the trees, and the final prediction is determined by averaging or voting the predictions from all the trees in the forest. Finally, cubist is a rule-based algorithm that combines decision trees with linear models. It creates a set of rules by recursively partitioning the data based on the predictor variables48. Each rule corresponds to a specific region of the feature space and predicts the response variable using a linear model. The algorithm iteratively builds a series of decision trees and linear models, optimising an objective function that balances accuracy and complexity.

We tuned the hyperparameters of each of the four machine-learning algorithms for both model formulations (Eqs. 1–2; Table 2.1). Then, for each model formulation separately, we combined the predictions of each tuned algorithm into the meta-learner, defined as a linear regression of the egg count (response variable) and the four algorithms’ predictions (covariates). Both meta-learners were used to predict the abundance of Ae. albopictus eggs over the period 2010–2022 on the training and validation datasets. The meta-learner trained with the four algorithms having as model formulation Eq. 1, i.e. the regression model, was also used to predict, and thus extrapolate, over the whole area of interest for the period 2010–2022.

Model validation

The egg observations were partitioned into one training and two testing datasets for the external and internal validation; (Fig. 2b). To conduct the external validation, i.e. using observations not used to train the models, we employed a random selection process choosing two VectAbundance’s ovitraps within each distinct NUTS2 level for every biogeographical region. This selection was limited to VectAbundance’s ovitraps with a minimum of three years’ worth of observations, guaranteeing the presence of a robust time series for validation. These observations were excluded from the training dataset allowing for an exhaustive coverage of the longitudinal and latitudinal gradient of the area of interest. We excluded Sicily from the external validation dataset because it hosts only one ovitrap and represents the southernmost observation in the area of interest (see Fig. S3.1 for the locations of the ovitraps used for the external validation). After excluding these stations, we defined the training dataset as all the observations spanning from 2010 to 2021 and the internal validation dataset as all the observations gathered in 2022.

As an additional validation, we also performed a 10-fold cross-validation on the training dataset by retaining, for each fold, 70% of the observations to train the model. The class of models used is either regression or autoregression, so the standard k-fold cross-validation can be implemented, as suggested by Hyndman and Athanasopoulos44 (Ch 5. Section 10). To estimate the model’s predictive error we estimated, for each station and validation dataset, the root mean squared error (RMSE) and the mean absolute error (MAE).

Deriving pseudo-phenological indexes: introducing the period-over-threshold

In addition to utilising the regression stacked model for predicting the average number of eggs for each week within a given year across the area of interest, we also aimed to derive estimates about the predicted seasonality of Ae. albopictus’ egg-laying activity. Different approaches have been proposed to compute seasonal indexes of mosquitoes like onset (i.e. beginning of the season), peak, and offset (i.e., end of the season49,50). However, these approaches assume a repeated and even sampling of the species of interest, which, unfortunately, is not the case across the sampling locations of our dataset. Therefore, here we propose and define a pseudo-seasonal index that we call the period-over-threshold (POT).

The POT represents the period in which the variable of interest, i.e. the average number of eggs, is above a certain threshold. Here, we define the POT as the number of weeks in which the weekly average number of eggs is equal to or higher than 55 eggs, the spatially and weekly aggregated average median number of eggs (excluding zeros) observed over the whole area of interest during the period 2010–2022. We acknowledge that the POT, as defined here, is a heuristic approach, and therefore we performed a sensitivity analysis varying the threshold to 20 and 125, defined by the average interquartile range (IQR) of the observed distribution.

Finally, we investigated if the observed and predicted POT have varied in time and space among the different biogeographical regions over the 2010–2022 period. We tested whether the length of the observed and estimated POT is affected by the year (quantitative) and the biogeographical regions (qualitative: Alpine/Continental/Mediterranean) and their interaction, using Generalised Linear Mixed Models (GLMMs) with Poisson error distribution and log link function, considering the ID of the VectAbundance’s ovitraps as a random factor. The same GLMM was applied to both the observational dataset used to train the regression-stacked model and a dataset of predictions for the period 2010–2022, generated by the regression-stacked model itself.

Results

Ovitraps dataset descriptive statistics

The 149 VectAbundance’s ovitraps are located in four European countries (Albania, France, Italy and Switzerland). Overall, 30 aggregated ovitraps were located in the Alpine biogeographical region, while 48 and 71 were located in the Continental and Mediterranean biogeographical regions, respectively. Most of the ovitraps were active during the period 2020–2022, with only a few stations that were monitored for more than three seasons32. 120 aggregate ovitraps were used to train the models, whilst 19 were retained for the external validation.

Model outputs

The random forest algorithm showed the highest regression coefficient in the regression stacked model and so resulted as the most important algorithm (Table S2.2), while the most important environmental predictors were the 3-week-lagged temperature and photoperiod (Fig. S2.3A). On the other hand, cubist was the most important algorithm for the stacked autoregressive model, with the 1-week-lagged value of observed eggs being the most important predictor (Fig. S.2.3B).

Both stacked models were able to capture the seasonal and interannual variability of the ovitraps time series in the training dataset and both validation datasets (Figs. 3, S3.2). A detailed representation of the external validations for both models, broken down at the location level, is available in SM3 in Figs. S3.3–S3.4 for the regression and autoregressive models respectively. The predicted values for both the internal and external validation matched the observation patterns in the three biogeographical regions, with the autoregressive model showing, in general, a closer association with the observations. The autoregressive model showed overall a higher R2 and lower RMSE and MAE compared to the regression model in the training and both validation datasets (Table 1; Fig. S3.5). For both model formulations, both RMSE and MAE are lower in the Alpine biogeographical region compared to the Continental and Mediterranean regions; however, RMSE and MAE values within the Continental and Mediterranean regions show no significant differences between their respective training and testing datasets (Fig. S3.6).

Median number of eggs predicted weekly by the regression model in the area of interest for the year 2022. The black lines represent the borders of the administrative areas of the countries of interest at the NUTS2 level. The grey areas are outside the area of interest. The map was created using R v4.334.

Spatial predictions

The spatio-temporal predictions of the stacked regression model for 2022 reveal seasonal and latitudinal variation in egg abundance across the study area (Fig. 4). Egg-laying activity begins in early spring, with the median number of eggs exceeding 50 from week 20 (mid-May) onwards. The peak of the season is estimated around week 30 (end of July), particularly in the Po and Rhone valleys and along the Adriatic, Ionian, and Tyrrhenian coasts. Egg abundance decreases after week 35 (end of August), but this decline follows a latitudinal and geographical gradient. In southern and coastal areas, predicted egg numbers remain above 100 through week 40 (early October), dropping below 50 only after week 45 (November). In alpine regions, egg-laying activity is restricted to warmer months, while in coastal areas, predictions indicate prolonged activity into late autumn.

Period-over-threshold

On average, the observed POT spans 7 (6–9 IQR) weeks for the Alpine biogeographical region, 20 (19–22 IQR) and 15 (14–16 IQR) weeks for the Continental and Mediterranean biogeographical regions, respectively. The predicted POT shows generally a shorter length, with 4 (3–5 IQR) weeks for the Alpine biogeographical region, and 17 (16–18 IQR) and 11 (9–12 IQR) weeks for the Continental and Mediterranean biogeographical regions respectively. The spatial representation of the predicted POT for the year 2022 (Fig. 5; POT IQR displayed in Fig. S3.7) shows a longer length of the POT in the Po Valley and coastal zones of the area of interest (POT > 20 weeks). Mountainous and foothills areas show, on average, short (POT < = 5 ) or absent POT.

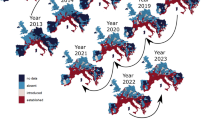

The Poisson GLMMs investigating the effect of the interaction between the year and the biogeographical regions on the POT show significant effects for all the explanatory variables and their interactions, except for the Alpine biogeographical region in the observed dataset (Table S3.8). The predicted values of the models trained on the observed and estimated POT showed a positive increase, independent from the reference year, for all the biogeographical regions but the Alpine in the observed dataset over the period 2010–2022 (Fig. 6).

Spatial representation of the predicted critical period-over-threshold (POT) for the year 2022 in the area of interest. White pixels are characterised by an average median weekly number of eggs always lower than 55. The black lines represent the borders of the administrative areas of the countries of interest at the NUTS2 level. The map was created using R v4.334.

Discussion

Ensemble modelling is a popular technique to mitigate the artefacts or errors that may arise from individual algorithm predictions. Among the different ensemble techniques available, stacking has recently risen as one of the approaches leading to a more robust and accurate final prediction20,21,22,23,51. In this study, we proposed a reproducible application of a stacked model to infer the spatio-temporal egg abundance of a species of interest, the Tiger mosquito Ae. albopictus. We stress that our approach can be replicated and applied to different case studies and species, as recently shown by Bonannella and colleagues20,21, if longitudinal observations on their abundance and phenology are available. The application of a stacked model on both regression and autoregressive model formulations resulted in reliable estimates of mosquito egg abundance, providing an important to support local public health authorities to better allocate monitoring and surveillance resources.

Predictive accuracy of the models

The performance metrics of the regression and autoregressive models indicated a consistently strong predictive accuracy throughout the entire time series. Furthermore, the values of RMSE and MAE displayed similarities between the internal and external validation datasets. The autoregressive model showed generally higher predictive performance than the regression model, having the lagged number of eggs observed as the most important predictive variable. This was not unexpected, since the preliminary exploratory analysis (SM 1.2), made with genuine regression models, displayed strong empirical autocorrelation, of order one, in the residuals. However, the high predictive accuracy of the autoregressive model has the drawback of not being able to spatially extrapolate its predictions outside the training dataset. Whilst this can be seen as a limitation, it offers the opportunity of having accurate estimates and forecasts in specific locations, allowing the model to be informed with local and high-quality environmental information, using e.g. weather station observations. On the contrary, the regression model allowed us to spatially extrapolate the predictions in areas that were not previously sampled. The median number of eggs predicted over the study area for the year 2022 matches the expected seasonal dynamic of the species. Though egg-laying activity might occur in March and April, it increases around week 20 (mid-May) and ends in early October following elevational and latitudinal gradients43,50,52. In the alpine areas, our spatial estimates resembled those obtained using different modelling techniques and training datasets (e.g53). Previous dynamical distribution modelling approach forecasting Ae. albopictus eggs abundance at high spatial (0.01 latitudinal and longitudinal degrees) and temporal (weekly) resolution over ten Balkan countries projected annual peaks in egg abundance between the summer months of August and September i.e. approximately from weeks 32 to 3854. The field investigation in Albania in 2023 has shown the peak of the season in July (weeks 28-29-30) and another peak at the end of August and beginning of September (weeks 35–36; personal communication of E. Velo). For the coastal areas of the Tyrrhenian Sea, the spatio-temporal prediction of the stacked regression model confirms the results of previous studies carried out in central Italy, where the peak of activity and the end of the season is expected at the end of August and November, respectively (Fig. 4;42,50). Interestingly, these estimates based on ovitrap data (i.e. collection of eggs) comply with independent estimates obtained from data acquired collecting a different life stage of the mosquito (i.e., host-seeking females) at the two opposite ends of Italy (Trentino and Sicily) that identified the beginning of the season in mid-June and mid-March and the peak of the season in early August and August-September, respectively55,56.

Period-over-threshold

The pseudo-phenological index POT computed for Ae. albopictus during the year 2022 also showed latitudinal and elevational gradients, with the Po Valley and coastal areas having generally longer POT than mountainous areas. In the coastal areas of the Tyrrhenian Sea, the estimated POT is between 15 and 20, decreasing to 5 weeks in low mountain areas and to zero in high mountain peaks, similar to what was described in previous studies42,50. The spatial pattern depicted in Fig. 5 resembles those representing the estimates Ae. albopictus seasonal length presented by Petrić et al.57. However, the estimates of Petrić et al.57, based on multiple conditional statements of temperature and photoperiod, show a generally longer period of activity of the species compared to the estimated POT. This is not unexpected, because the two outputs are intrinsically different: the POT measures the length of the period over a user-defined threshold, whilst Petrić et al.57 have estimated the length of the period of activity of the mosquito considering the environmental conditions triggering eggs hatching, which in Mediterranean areas can begin in early March though at low density57.

In both the Continental and Mediterranean biogeographical regions, both observed and estimated POT durations have been increasing by approximately one week every year. This trend suggests a potential direct impact of global warming on the abundance of this species, as discussed in previous studies50,58,59,60,61. However, it is also essential to consider that the prolonged POT duration might be influenced by other factors, such as the increased monitoring efforts and the expanding range of the insect, leading to higher observed counts and longer POT periods.

Other threshold-based indexes have been proposed specifically for Ae. albopictus, but those are mostly epidemiological indexes (e.g62,63). We believe that the strength of the POT method lies in its broad interpretability and applicability. This approach can be employed not only in spatial epidemiology applications, as demonstrated in our case study but also in monitoring other alien species or supporting biological conservation efforts. It enables the identification of locations and periods when a particular population falls below or surpasses a defined threshold, signalling the need for targeted local interventions.

Limitations and future perspectives

As for most ecological models, one of the main limitations of these results relies on the quantity and quality of the training dataset64. First of all, egg observations were pooled from ovitraps having different volumes, shapes, oviposition substrates, revisiting times, etc32. This, unfortunately, is a limitation related to the different sampling and monitoring schemes employed by the different institutions32. Despite the preprocessing operation on the observations collected by the ovitraps, some of these sources of variability have likely influenced our results and therefore should be taken into account while interpreting them. Therefore, we want to highlight the importance of carrying out reproducible and comparable sampling schemes following the most updated standards for ovitraps monitoring, as those presented as the outcome of the AIM-COST cost action by Miranda et al.65.

Our dataset is also spatially biased because most of the observations are spatially clustered in north-central Italy, especially in the Emilia-Romagna region, where one of the most consistent and long-lasting surveillance programs has been carried out since 2010. The observations coming from this region had likely the highest quality, having been sampled continuously every two weeks from 2010 onwards. Spatial clustering is known to bias the models’ estimates and predictions66 and therefore has likely produced sub-optimal predictions in the southern part of the area of interest. This detrimental aspect of our outputs can only be resolved by increasing the sampling effort in the southern part of the study area.

Another potential source of variability in the training dataset is the effect of vector control practices affecting the abundance of collected eggs. Pest control agencies act to limit the abundance of the species and reduce the nuisance the bites are causing to the population67. Unfortunately, this is an effect that we cannot control, as we do not have access to the location and period of each pest containment treatment carried out in the area and period of interest. In addition to the coarse resolution of the climatic predictors, which may not fully capture fine-scale climatic variations influencing the mosquito life-cycle, we acknowledge the potential value of other relevant predictors not included in this study, such as land use/land cover and human population density. However, the exclusive placement of ovitraps in urban areas limits the availability of contrasting data needed to effectively incorporate these variables.

Despite these limitations, the proposed framework seems feasible to be implemented to produce both local and continental scale predictions and forecasts, contributing to supporting the stakeholders in their effort against Ae. albopictus. Using e.g. regional circulation models and/or weather generators, the methodology presented here can be used to produce estimates for the next seasons under different climatic scenarios. Interestingly, the presented methodology can be implemented and corrected during the season by including the results of the monitoring activities in the training dataset. The estimates of these models can also be compared to estimates produced by other correlative models (e.g68). , or mechanistic models such as albopictus69 and dynamAedes7, producing a plethora of models’ estimates accounting for different aspects of the biological system studied.

By employing the results of our modelling approach, public health authorities can make informed decisions regarding the implementation of control measures, allocation of resources, and targeted interventions to mitigate the risks posed by invasive mosquitoes and safeguard human and animal health. The latter aspect has gained particular interest during the past two decades when the impact of invasive species on public health has become more evident (e.g.,70,71). Apart from the public health aspect, we believe our work has a broader scope, providing a tool that can be adapted to infer the spatio-temporal abundance and seasonality of different species of interest.

Data availability

All the analyses were performed in R 4.3 (R Core Team 2023). All the R scripts used for the analysis are available at the GitHub repository https://github.com/danddr/stackedML. The R scripts are shared with detailed comments to foster the methodology reproducibility and its application to case studies and species different to invasive mosquitoes.

References

Fand, B. B., Choudhary, J. S., Kumar, M. & Bal, S. K. Phenology modelling and GIS applications in pest management: A tool for studying and understanding insect-pest dynamics in the context of global climate change. Approaches Plant Stress Manag. 107–124 (2014).

Ettinger, A. K., Chamberlain, C. J. & Wolkovich, E. M. The increasing relevance of phenology to conservation. Nat. Clim. Change 12(4), 305–307 (2022).

Burkett-Cadena, N. D. et al. Host reproductive phenology drives seasonal patterns of host use in mosquitoes. PLoS ONE 6(3), e17681 (2011).

Tran, A. et al. A rainfall-and temperature-driven abundance model for Aedes albopictus populations. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 10(5), 1698–1719 (2013).

Marini, G. et al. First report of the influence of temperature on the bionomics and population dynamics of Aedes koreicus, a new invasive alien species in Europe. Parasites Vectors 12, 1–12 (2019).

Pfab, F. et al. Optimized timing of parasitoid release: A mathematical model for biological control of Drosophila suzukii. Theor. Ecol. 11, 489–501 (2018).

Da Re, D. et al. dynamAedes: A unified modelling framework for invasive Aedes mosquitoes. Parasites Vectors 15(1), 1–18 (2022).

Tjaden, N. B., Thomas, S. M., Fischer, D. & Beierkuhnlein, C. Extrinsic incubation period of dengue: Knowledge, backlog, and applications of temperature dependence. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 7(6), e2207 (2013).

Guisan, A., Thuiller, W. & Zimmermann, N. E. Habitat Suitability and Distribution Models: With Applications in R (Cambridge University Press, 2017).

Edwards, C. B. & Crone, E. E. Estimating abundance and phenology from transect count data with GLMs. Oikos 130(8), 1335–1345 (2021).

Hortal, J., Jiménez-Valverde, A., Gómez, J. F., Lobo, J. M. & Baselga, A. Historical bias in biodiversity inventories affects the observed environmental niche of the species. Oikos 117(6), 847–858 (2008).

Fourcade, Y. Fine-tuning niche models matters in invasion ecology. A lesson from the land planarian Obama nungara. Ecol. Model. 457, 109686 (2021).

Bazzichetto, M. et al. Sampling strategy matters to accurately estimate response curves’ parameters in species distribution models. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 32, 1717–1729 (2023).

Da Re, D. et al. USE it: Uniformly sampling pseudo-absences within the environmental space for applications in habitat suitability models. Methods Ecol. Evol. 14, 2873–2887. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.14209 (2023a).

Araújo, M. B. & New, M. Ensemble forecasting of species distributions. Trends Ecol. Evol. 22(1), 42–47 (2007).

Pearson, R. G. et al. Model-based uncertainty in species range prediction. J. Biogeogr. 33(10), 1704–1711 (2006).

Marmion, M., Parviainen, M., Luoto, M., Heikkinen, R. K. & Thuiller, W. Evaluation of consensus methods in predictive species distribution modelling. Divers. Distrib. 15(1), 59–69 (2009).

Hao, T., Elith, J., Guillera-Arroita, G. & Lahoz-Monfort, J. J. A review of evidence about use and performance of species distribution modelling ensembles like BIOMOD. Divers. Distrib. 25(5), 839–852 (2019).

Wolpert, D. H. Stacked generalization. Neural Netw. 5(2), 241–259 (1992).

Bonannella, C. et al. Forest tree species distribution for Europe 2000–2020: mapping potential and realized distributions using spatiotemporal machine learning. PeerJ 10, e13728. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.13728 (2022).

Bonannella, C., Hengl, T., Parente, L. & de Bruin, S. Biomes of the world under climate change scenarios: Increasing aridity and higher temperatures lead to significant shifts in natural vegetation. PeerJ 11, e15593. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.15593 (2023).

El Alaoui, O. & Idri, A. Predicting the potential distribution of wheatear birds using stacked generalization-based ensembles. Ecol. Inf. 75, 102084 (2023).

Oeser, J. et al. The Best of Two Worlds: Using Stacked Generalisation for Integrating Expert Range Maps in Species Distribution Models e13911 (Global Ecology and Biogeography, 2024).

Roche, B. et al. The spread of Aedes albopictus in metropolitan France: Contribution of environmental drivers and human activities and predictions for a near future. PloS ONE 10(5), e0125600 (2015).

Ibáñez-Justicia, A. Pathways for introduction and dispersal of invasive Aedes mosquito species in Europe: A review. J. Eur. Mosq. Control Assoc. 38, 1–10 (2020).

Rezza, G. et al. Infection with chikungunya virus in Italy: An outbreak in a temperate region. Lancet 370(07), 1840–1846. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140- (2007).

Venturi, G. et al. Detection of a chikungunya outbreak in central Italy, August to September 2017. Eurosurveillance 22(17), 00646. https://doi.org/10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2017.22.39.17-00646 (2017).

Brady, O. J. & Hay, S. I. The first local cases of Zika virus in Europe. Lancet 394(10213), 1991–1992 (2019).

Barzon, L. et al. Autochthonous dengue outbreak in Italy 2020: Clinical, virological and entomological findings. J. Travel Med. 28(8), taab130 (2021).

Caputo, B. & Manica, M. Mosquito surveillance and disease outbreak risk models to inform mosquito-control operations in Europe. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 39, 101–108 (2020).

Lippi, C. A. et al. Trends in mosquito species distribution modeling: Insights for vector surveillance and disease control. Parasites Vectors 16(1), 302 (2023).

Da Re, D. et al. VectAbundance: A spatio-temporal database of Aedes mosquitoes observations. Sci. Data 11(1), 636 (2024).

Cervellini, M. et al. A grid-based map for the Biogeographical Regions of Europe. Biodivers. Data J. 8 (2020).

R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, 2023). https://www.R-project.org/

Boehmke, B. & Greenwell, B. M. Chapter 15: Stacked models. In Hands-on Machine Learning with R (CRC, 2019).

Zhou, Z. H. Ensemble Methods: Foundations and Algorithms (Chapman and Hall/CRC, 2012).

Toma, L., Severini, F., Di Luca, M., Bella, A. & Romi, R. Seasonal patterns of oviposition and egg hatching rate of Aedes albopictus in Rome. J. Am. Mosq. Control Assoc. 19, 19–22 (2003).

Becker, N. et al. Mosquitoes and their Control (Springer Science & Business Media, 2010).

Roiz, D., Neteler, M., Castellani, C., Arnoldi, D. & Rizzoli, A. Climatic factors driving invasion of the tiger mosquito (Aedes albopictus) into new areas of Trentino, Northern Italy. PloS ONE 6(4), e14800 (2011).

Roiz, D., Rosà, R., Arnoldi, D. & Rizzoli, A. Effects of temperature and rainfall on the activity and dynamics of host-seeking Aedes albopictus females in Northern Italy. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 10(8), 811–816 (2010).

Marini, G. et al. Influence of temperature on the life-cycle dynamics of Aedes albopictus population established at temperate latitudes: A laboratory experiment. Insects 11(11), 808 (2020).

Romiti, F. et al. Aedes albopictus (Diptera: Culicidae) monitoring in the Lazio region (central Italy). J. Med. Entomol. 58(2), 847–856 (2021).

Carrieri, M. et al. Effects of the weather on the seasonal population trend of Aedes albopictus (Diptera: Culicidae) in Northern Italy. Insects 14(11), 879 (2023). https://doi.org/10.3390/insects14110879

Hyndman, R. J. & Athanasopoulos, G. Forecasting: Principles and Practice 3rd edn (OTexts: Melbourne, Australia, accessed on 17 October 2023); https://otexts.com/fpp3/ (2021).

Friedman, J. H. Greedy Function Approximation: A Gradient Boosting Machine 1189–1232 (Annals of Statistics, 2001).

Elith, J., Leathwick, J. R. & Hastie, T. A working guide to boosted regression trees. J. Anim. Ecol. 77(4), 802–813 (2008).

Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 45, 5–32 (2001).

Quinlan, J. R. Learning with continuous classes. In 5th Australian Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Vol. 92 343–348 (1992).

Rosà, R. et al. Early warning of West Nile virus mosquito vector: Climate and land use models successfully explain phenology and abundance of Culex pipiens mosquitoes in north-western Italy. Parasites Vectors 7, 1–12 (2014).

Romiti, F., Casini, R., Magliano, A., Ermenegildi, A. & De Liberato, C. Aedes albopictus abundance and phenology along an altitudinal gradient in Lazio region (central Italy). Parasites Vectors 15(1), 1–11 (2022).

Hancock, P. A. et al. Mapping trends in insecticide resistance phenotypes in African malaria vectors. PLoS Biol. 18(6), e3000633 (2020).

Lencioni, V. et al. Multi-year dynamics of the Aedes albopictus occurrence in two neighbouring cities in the Alps. Eur. Zool. J. 90(1), 101–112 (2023).

Ravasi, D. et al. Risk-based mapping tools for surveillance and control of the invasive mosquito Aedes albopictus in Switzerland. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19(6), 3220 (2022).

Tisseuil, C. et al. Forecasting the spatial and seasonal dynamic of Aedes albopictus oviposition activity in Albania and Balkan countries. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 12(2), e0006236 (2018).

Guzzetta, G. et al. Potential risk of dengue and chikungunya outbreaks in northern Italy based on a population model of Aedes albopictus (Diptera: Culicidae). PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 10(6), e0004762 (2016).

Torina, A. et al. Modelling time-series Aedes albopictus abundance as a forecasting tool in urban environments. Ecol. Indic. 150, 110232 (2023).

Petrić, M. et al. Seasonality and timing of peak abundance of Aedes albopictus in Europe: Implications to public and animal health. Geospat. Health 16(1) (2021).

Kramer, I. M. et al. The ecophysiological plasticity of Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus concerning overwintering in cooler ecoregions is driven by local climate and acclimation capacity. Sci. Total Environ. 778, 146128 (2021).

Oliveira, S., Rocha, J., Sousa, C. A. & Capinha, C. Wide and increasing suitability for Aedes albopictus in Europe is congruent across distribution models. Sci. Rep. 11(1), 9916 (2021).

Del Lesto, I. et al. Is Asian tiger mosquito (Aedes albopictus) going to become homodynamic in Southern Europe in the next decades due to climate change? R. Soc. Open Sci. 9(12), 220967 (2022).

Lührsen, D. S. et al. Adult Aedes albopictus in winter: Implications for mosquito surveillance in Southern Europe. Lancet Planet. Health 7(9), e729–e731 (2023).

Carrieri, M., Angelini, P., Venturelli, C., Maccagnani, B. & Bellini, R. Aedes albopictus (Diptera: Culicidae) population size survey in the 2007 Chikungunya outbreak area in Italy. II: Estimating epidemic thresholds. J. Med. Entomol. 49(2), 388–399 (2012).

Aryaprema, V. S., Steck, M. R., Peper, S. T., Xue, R. D. & Qualls, W. A. A systematic review of published literature on mosquito control action thresholds across the world. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 17(3), e0011173 (2023).

Cayuela, L. et al. Species distribution modeling in the tropics: Problems, potentialities, and the role of biological data for effective species conservation. Trop. Conserv. Sci. 2(3), 319–352 (2009).

Miranda, M. Á. et al. AIMSurv: First pan-European harmonized surveillance of Aedes invasive mosquito species of relevance for human vector-borne diseases. Gigabyte 2022 (2022).

Sillero, N. & Barbosa, A. M. Common mistakes in ecological niche models. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 1–14 (2020).

Ravasi, D., Parrondo Monton, D., Tanadini, M. & Flacio, E. Effectiveness of integrated Aedes albopictus management in southern Switzerland. Parasites Vectors 14 (1), 1–15 (2021).

Georgiades, P., Proestos, Y., Lelieveld, J. & Erguler, K. Machine learning modeling of Aedes albopictus habitat suitability in the 21st century. Insects 14(5), 447 (2023).

Erguler, K. et al. Large-scale modelling of the environmentally-driven population dynamics of temperate Aedes albopictus (Skuse). PloS ONE 11(2), e0149282 (2016).

Zink, K., Vogel, H., Vogel, B., Magyar, D. & Kottmeier, C. Modeling the dispersion of Ambrosia artemisiifolia L. pollen with the model system COSMO-ART. Int. J. Biometeorol. 56, 669–680 (2012).

Schaffner, U. et al. Biological weed control to relieve millions from Ambrosia allergies in Europe. Nat. Commun. 11(1), 1745 (2020).

Acknowledgements

The study was supported by the Italian Ministry of University and Research (MUR) PRIN2020 “Tackling mosquitoes in Italy: from citizen to bench and back” (N. 2020XYBN88). This study was partially funded by EU grant 874850 MOOD and is catalogued as MOOD 098. This study was partially supported by EU funding within the MUR PNRR Extended Partnership initiative on Emerging Infectious Diseases (Project no. PE00000007, INF-ACT). This study was partially supported by the Open-Earth-Monitor Cyberinfrastructure project. The Open-Earth-Monitor Cyberinfrastructure project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon Europe research and innovation program under grant agreement No. 101059548. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of the authors and don’t necessarily reflect the views of the European Commission. Gionata Stancher and Federica Bertola thank the municipalities belonging to Comunità della Vallagarina and Comunità Alto Garda e Ledro. Monitoring activities in Trento were financed by the Trento Municipality. Domenico Otranto and Riccardo Paolo Lia thank Natalizia Palazzo for the support given during the mosquito monitoring activities in the city of Bari.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Daniele Da Re, Beniamino Caputo, Alessandra della Torre and Roberto Rosà conceived the study; Daniele Da Re and Roberto Rosà designed the methodology, with relevant contributions from Carmelo Bonannella, Giovanni Marini, Fabrizio Laurini and Mattia Manica; Nikoleta Anicic, Alessandro Albieri, Paola Angelini, Daniele Arnoldi, Federica Bertola, Beniamino Caputo, Claudio De Liberato, Enkelejda Velo, Eleonora Flacio, Alessandra Franceschini, Perparim Kadriaj, Valeria Lencioni, Irene Del Lesto, Francesco La Russa, Riccardo Paolo Lia, Fabrizio Montarsi, Francesco Gradoni, Gregory L’Ambert, Federico Romiti, Gionata Stancher, Fabiana Zandonai collected the data; Daniele Da Re, Carmelo Bonannella, Giovanni Marini, Fabrizio Laurini, Mattia Manica and Roberto Rosà analysed the data; Daniele Da Re led the writing of the manuscript. All authors contributed critically to the drafts and gave final approval for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Da Re, D., Marini, G., Bonannella, C. et al. Modelling the seasonal dynamics of Aedes albopictus populations using a spatio-temporal stacked machine learning model. Sci Rep 15, 3750 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87554-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87554-y

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

A warming welcome? Belgium’s increasing suitability for Aedes albopictus

Parasites & Vectors (2025)