Abstract

In this paper, porous Cu with different porosity and pore size has been successfully prepared by the well-known lost carbamide sintering method. The effects of the space holder size on the pore structure and mechanical properties of porous Cu were studied with a wide porosity range. The results showed that the particle size of space holder has an effect on the porosity, pore size, elastic modulus, yield strength, densification stress & strain, energy density, plateau stress and fitting curve of porous Cu, but the law was complex when compared with the content. The correlation between the relative elastic modulus and the relative density of porous Cu was square exponential which can be well described by the standard Gibson-Ashby model. However, the correlation between the relative yield strength and the relative density of porous Cu was more suitable to describe by the power exponent instead of 3/2 which can be well described by the modified Gibson-Ashby model. The results indicated that the effect of space holder content on the pore structure and mechanical properties of porous Cu was more significant and regular than that of particle size, but the effect of space holder size cannot be ignored. The results of this study will provide reference for the design and preparation of porous Cu with different pore sizes in the future.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Porous Cu and its foams are attractive in the fields of energy and environmental as well as thermal management because of their excellent comprehensive properties1,2,3. The space holder technique (SHT) based on powder metallurgy was widely used to fabricate porous Cu with high porosity and a solid skeleton. In this method, the pore structure (such as porosity, pore size, pore connectivity and pore shape) of porous Cu was adjusted by the parameter (such as content, size and shape) of space holder particles. Due to this advantage, more and more attention has been paid to the preparation of SHT porous Cu in recent years4,5,6,7,8.

The preparation of SHT porous Cu can be traced back to 20059, where Zhao et al. described a lost carbonate (K2CO3) sintering process for manufacturing open Cu foams with porosity in the range 50–85% and cell sizes in the range 53–1500 μm. This work was followed by porous titanium, stainless steel, superalloy10 and Al foams11 prepared by the same method. Since then, sodium chloride (NaCl)12 and carbamide13 had been used as space holders to fabricate porous Cu. Recently, porous Cu with ultrahigh porosity has been prepared by using carbamide as a space holder, which was comparable to electrodeposition Cu foams14. In addition, the effects of the space holder shape on the pore structure and mechanical properties of porous Cu with a wide porosity range has also been studied15. However, the effects of the space holder size on the pore structure and mechanical properties of porous Cu were insufficient. The amount of porosity and pore size were the most important factors that influence the compressive behavior of porous Cu, as reported in previous studies16,17,18. Zou et al.16 revealed that the mechanical strength increases with decreasing pore size in the linear elastic and plateau regions, but decreases with decreasing pore size in the densification region. But a little earlier Parvanian et al.18 found that the mechanical properties of the porous Cu would improve as a consequence of porosity reduction, while similar relation also exists as average pore sizes decrease. In other studies, Guo et al.19 reported that the mechanical properties of aluminum composite foams hardly depend on the size of NaCl particles. Hajizadeh et al.20 indicated that increasing the NaCl particle size leads to decreasing the mentioned mechanical properties except the energy absorption efficiency and increasing the porosity of open aluminum foams. Tejeda-Ochoa et. al21, the elastic modulus and yield strength of porous titanium decreased with the increasing size of the NaCl space holder while the porosity changed irregularly. Luo et al.22 showed that the elastic modulus of titanium foam decreased with the increasing size of the Mg particles while the porosity decreased. Sharma et al.23 demonstrated that the Cu foams processed with a smaller-sized space holder were found to exhibit better electrical and mechanical properties than those processed with a coarser-sized space holder, while the porosity the porosity decreases first and then increases with the increase of spacer size acrawax, etc. From the above studies, it can be seen that not only porous Cu, but also other porous metals by SHT, their pore structure and mechanical properties were affected by the size of the space holder, which was also the difficulty and big challenge of current research on porous Cu.

Therefore, this paper attempts to clarify the effect of space holder size on the pore structure and mechanical properties of porous Cu with a wide porosity range. In this paper, carbamide was chosen as the space holder because it can be volatilized into gas at a lower temperature than potassium carbonate and sodium chloride and overflow the compacts. The preparation process of one step of heat treatment was the same as before, except that the carbamide was spherical with a narrower particle size range. The mechanical behavior of porous metals at various scales (meso and nano) has been extensively addressed in the literatures24,25. The standard and modified Gibson-Ashby model was addressed to study the correlations between pore structure and mechanical properties of the obtained porous Cu.

Materials and methods

Electrolytic Cu powder with coralloid shape (see Fig. 1a) was used as raw material. The purity and size of Cu powder were about ~ 99.9% and ≤ 50 μm, respectively. Spherical carbamide with two sizes (1.7-2 mm, Figs. 1b and 2 mm, Fig. 1c) was used as space holder. The total volume of porous Cu was designed as 20 mm in diameter and 8 mm in height and the volume content of space holder was increased from 10% to 80 vol% at intervals of 10%. According to the density of Cu powder (8.96 g/cm3) and carbamide (1.335 g/cm3), the weight of them as increase of spacer content were 20.26, 18.01, 15.76, 13.50, 11.25, 9.00, 6.75, 4.50 g for Cu powder and 0.34, 0.67, 1.01, 1.34, 1.68, 2.01, 2.35, 2.68 g for carbamide particles, respectively. Considering that Cu powder has small size and were easy to lose, their mass was more than 0.05 g.

The weighed Cu powder and carbamide particles were poured into a mortar with small amount of anhydrous ethanol added in the mixing process. Then the steel mould with 20 mm in inner diameter containing mixtures was axially pressed under a pressure of 200 MPa and a holding time of 0.5 min. Then the green compacts placed on a layer metal mesh support in a porcelain boat were heated by the improved one step (see Fig. 1d) in a vacuum tube furnace. The step can be divided into two parts: the temperature increased from room temperature (Troom) to 400 °C within 300 min and holding the temperature for 10 min with purpose for removing carbamide particles in part-I, then the temperature continue to increase to 800 °C within 40 min and holding the temperature for 2 h with purpose for sintering Cu powder in part-II. After that, the furnace cools to room temperature.

The mass volume method was applied to calculate the porosity of the obtained porous Cu samples measured by weight and dimensions. It first calculates the density according to the weight and volume, and then divides the density of pure Cu as the relative density, and then subtracts the relative density with 1 as the porosity which was expressed as a percentage. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM, FEI Company, Hillsboro, OR, USA) was used to observe the surface and cross section microstructure of the porous Cu samples. The surface was observed in order to see the internal structure of the porous Cu without damaging the structure of the samples. The cross section was observed in order to calculate the pore size of the porous Cu samples which were cut laterally and longitudinally by a wire cutting machine. Before SEM observation, the samples were cleaned by ultrasonic wave and then dried for use. XRD was used to detect the phase of Cu powder and porous Cu samples compared with the standard card.

The quasi-static uniaxial compression test by an electronic universal testing machine (type: UTM-5105) with the moving rate of 2 mm/min was carried out to study the compressive properties of the cylindrical porous Cu samples at room temperature according to the ISO-13,314 standard26. Each compressive property was obtained using the average results of three samples. The relative average deviation was used to quantitatively describe the effect of space holder size on porosity and mechanical properties of porous Cu. It was defined as the absolute value of the difference between two values and the average divided by the average in percentage. If the relative average deviation does not exceed 1%, the error between the two data was considered negligible, and vice versa. The symbols “+”, “-” and “=” indicate that the large-size porous Cu was “greater than”, “less than” and “equal to” the small-size porous Cu, respectively.

Results and discussion

Effect of space holder size on pore structure

The digital images of the present porous Cu samples obtained by using different sizes of spherical carbamide particles with volume content between 10 and 80% were shown in Fig. 2(a) and (b). Among them, (a) was porous Cu by using smaller (i.e. 1.7–2 mm) space holder size (SSH-Porous Cu for short), (b) was porous Cu by using larger (i.e. 2–3 mm) space holder size (LSH-Porous Cu for short). The arrows in the figure indicate the change trend of the space holder content, which also applies to the right figure. It can be seen that much more holes were found on the surface of samples as the increasing of spacer content and the surface of some samples with low space contents was grey because we have ground the surface of these samples, due to the specimen bag placed on these samples was sealed.

Digital images of porous Cu samples fabricated by using different sizes of spherical carbamide as space holder with volume content between 10–80%: (a) 1.7–2 mm, (b) 2–3 mm. Surface SEM images of the present porous Cu samples adding 80% volume content of space holder with particle size of (c-e) 1.7–2 mm and (b-d) f-h mm at different magnifications: (c) 100 ×, (d, g) 2000×, (e, h) 10,000×, (f) 200×.

The surface SEM images of the present porous Cu samples adding 80% volume content of space holder with different particle sizes was shown in Fig. 2(c-h). The clearly pores were generated from the removal of space holder particles. For such pores, we usually refer to them as macropores in Fig. 2c and f. The cell-walls connecting these macropores were formed by sintering of Cu powders and they don’t look completely dense in Fig. 2d and g. Upon further magnification, many tiny pores can be seen in the skeleton (see Fig. 2e and h). These tiny pores arise from the gaps between Cu powders and were called as micropores. The volume fraction of macropores and micropores was the porosity of porous Cu with a two-scale structure13. Thick and smooth sintering neck were formed after the high-temperature sintering of Cu powders, which indicates that the sintering was sufficient under the existing sintering system7.

Figure 3 shows the XRD patterns of the pure copper powder and representative porous copper samples. The diffraction peaks of only pure copper can be identified from the patterns. This indicates that no measurable remnant carbamide was present within the porous Cu samples after the decomposition of the space holders by heating. This also confirms that the use of carbamide as space holders, whether high content or low content, whether small particle size or large particle size, will not cause chemical pollution of the Cu matrix. The space holder does not bring chemical pollution was an important prerequisite for the preparation of high purity porous Cu, which has similar requirements in previous studies4,5.

Porosity was the most important single structural feature for a porous material27. The porosity of porous Cu calculated from the mass volume method with relative average deviation between different space holder size was shown in Fig. 4. It was found that the weight of porous Cu was close to that of Cu powder, indicating that the preparation process follows mass conservation (see Fig. 4a). However, the diameter and height of porous Cu differ greatly from the design value (see Fig. 4b and c). At the same time, the diameter of porous Cu changes irregularly with the increase of spacer content but the height decreases gradually. Compared with SSH-Porous Cu for the same content of space holder, the diameter and height of LSH-Porous Cu C are mostly reduced, especially the latter. As a result, the porosity of SSH-Porous Cu and LSH-Porous Cu for the same volume fraction of space holder was different (see Fig. 4d).

In addition to being different, we can see that the porosity of the porous Cu increased as the increase of spacer content. The difference between spacer content and porosity at low contents was higher than high contents. This is because at low contents (10–40%), a large number of microscopic pores exist and the volume of macroscopic large pores was equivalent to the volume of space holder, resulting in the porosity of porous Cu was much larger than the corresponding space holder content (difference between the two ~ 7–22%). When the content of space holder was higher (50–80%), carbamide as a soft material particle was conducive to the transfer of stress during the pressing process, resulting in a higher density of raw compact and a significant reduction of microscopic pores, as well as a dimensional shrinkage of macroscopic large pores during the densification of copper powder. As a result, the porosity of porous Cu was close to the space holder content (difference between the two ~ 0.4-5%).

On the other hand, the change of porosity with the particle size of space holder does not show a consistent change law. According to the relative average deviation, the relative average deviation of porosity was greater than 1% when the space holder content was 10, 20, 30, 40, 60 and 80%, which indicates that the space holder size has a significant effect on the porosity of porous Cu with these contents. However, the difference was that when the space holder content was 10, 20, 40, 60 and 80%, the porosity of porous Cu decreases significantly with the increase of the space holder size, while when the space holder content was 30%, the porosity of porous Cu increases significantly with the increase of the space holder size. The reason was that the diameter contraction of SSH-Porous Cu was larger, resulting in higher porosity of LSH-Porous Cu. For spacer content 50 and 70%, the relative average deviation of porosity of porous Cu was less than 1%, that is, the effect of space holder size on the porosity of porous Cu with these contents was negligible. In other words, the size of space holder has an effect on the porosity of porous Cu, but there was no obvious rule.

ConfirmThe relationship between porosity and spacer content of porous metals had been proved to be linear28 and experimentally verified29,30. After dimensionless treatment, the porosity in Table 1 and the corresponding spacer content were linearly fitted, and the results were shown in Fig. 5. The fitting degree of the two lines was very close to 1, indicating that the porosity (P) of porous Cu used in this study can be described in a linear relationship with the spacer content (x), as shown the below two formulas. The space holder size of has negligible influence on the slope of linear equation, but has obvious influence on the intercept through calculation.

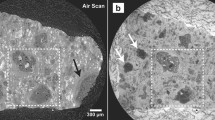

The macro-morphology of the cross-section of the porous Cu samples was shown in Fig. 6. The circular and square cross-section were perpendicular and parallel to the pressing direction, respectively. The upper and lower arrows indicate an increase in the space holder content from 10 to 80%. As can be seen from the figure, the shape of the pores was different in the two cross sections. In the cross-section perpendicular to the pressing direction (i.e. circular cross-section), the pores maintain the ball shape of the space holder. However, the pores become elliptical in the cross-section parallel to the pressing direction (i.e. square cross-section). This is due to the deformation of the space holders under the influence of pressure during the pressing process from spherical to ellipsoidal. The pores left were ellipsoidal when these space holder particles were removed during the heating process. Since the pore becomes elliptical, we decide to describe the pore size in terms of long axis and short axis. The long axis was the size on the section perpendicular to the pressing direction and the short axis was the size on the section parallel to the pressing direction. For the long axis, the maximum size of the selected pore was required to be no less than the minimum diameter of the corresponding space holder. For the short axis, the selected size should not be higher than the maximum diameter of the corresponding space holder in parallel to the pressing direction. Since the pore connectivity increases with the increase of spacer content and the decrease of spacer size, it was observed that the pores were connected to each other when the spacer content reached 50%. Moreover, the degree of connectivity between the pores gradually increased as the increase of spacer content, as shown in Fig. 7. The capital letter abbreviation CS and VS stand for cross and vertical section, respectively.

The images in Fig. 7 were the section SEM images of porous Cu samples with volume content between 50 and 80% using different spacer sizes of 1.7–2 mm and 2–3 mm. For connected pores, the measurement method of long axis was to measure the maximum distance between the two pores of this section, and the short axis was to measure the minimum distance between the two pores of this section. Based on the above rules, we measure the long axis and short axis of the elliptic pore size of the samples. Also, the axis ratio was applied to describe the ration between the long axis and short axis for an elliptic pore. The closer the value is to 1, the closer the pore is to the spherical, and vice versa, the closer it is to the elliptical.

The long axis, short axis and axis ratio of the pore sizes for the porous Cu samples was shown in Table 1. It can be seen that the long axis of LSH-Porous Cu was higher than that of SSH-Porous Cu for the same space holder content apart from the content of 80%. But for the short axis, the LSH-Porous Cu was higher than the SSH-Porous Cu for all contents. This was well understood because uses a larger space holder size was used in LSH-Porous Cu. For 80% content, the reason why the long axis of SSH-Porous Cu is higher than that of LSH-Porous Cu is that a large number of pores were interconnected to form an open-cell structure, and the smaller the pore size, the more conducive to connectivity. When these pores were connected, a pore with a larger size will be formed. The axis ratios in most cases with the diameter of the spacer size of 2–3 mm were higher than those of the samples of 1.7–2 mm, due to the larger the diameter of the space holder was, the larger the deformation of the forced space holder will be during pressing. However, when the spacer contents were 50% and 80%, the samples with space holder size of 1.7–2 mm were much larger than those with space holder size of 2–3 mm. For 50%, we suspect that the porous Cu at this content has shifted from closed to open, but has not yet formed open structure. At this time, the pores left by the space holder removal will shrink in size during the sintering process, especially in parallel to the pressing direction. Because of this reason, the pore axial ratio of SSH-Porous Cu was higher than that of LSH-Porous Cu. For 80%, For 80%, it is because a large number of pores were connected to each other, causing the long axis to be longer and the short axis to be shorter, resulting in a higher axial ratio for SSH-Porous Cu.

Compared with the particle size, the effect of space holder content on the pore size of porous Cu was not obvious. However, we should see that when the spacer content exceeds 50%, the pore size of porous Cu was significantly higher than the first four low contents. This is due to the fact that from 50% onwards, porous Cu gradually forms an open-cell structure. Since the holes were connected to each other, the pore size increases. Particularly, when the spacer content was 80%, it was almost difficult to observe independent pores and all pores were basically interconnected. In this way, the pore size of the porous Cu samples with 80% spacer content has another transition. For this content of porous Cu, using a smaller spacer size obtain a larger pore size. This is because that the pore connectivity was increased with the decrease of spacer size.

Effect of space holder size on mechanical properties

The compressive stress-strain curves of the present porous Cu samples were shown in Fig. 8. The stress of all curves increased with the increase of strain and all curves were smooth. Due to this property, the fabricated porous Cu samples exhibit compressive deformation characteristics of plastic porous materials which consist of typical three regions, i.e. elastic, plateau and densification regions12,31. The stress plateau of the curve was gradually obvious with the increase of spacer content, especially for the spacer content between 60 and 80%. Compared with SPC, there was no significant change for the curves of LPC. In other words, the particle size of space holder has relatively little influence on the stress-strain curve of porous Cu relative to the content. Figure 9 shows the digital images of the porous Cu after the compression test. As the same, the upper layer was the 1.7–2 mm samples and the bottom layer was the samples using 2–3 mm spacer size, respectively. It can be seen from the figure that the degree of deformation of porous Cu samples becomes more and more severe with the increase of space holder content from 10 to 80%. Specially, the porous Cu samples have been broken around when the space holder content between 60 and 80%. However, the stress reduction was not reflected in the stress-strain curves in Fig. 8. Therefore, it was difficult to directly obtain the densification stress and its strain directly from the stress-strain curve, because the stress continues to uptrend with the increase of strain19.

At high content, it has two turns in the curve. In the first turn, it goes from elastic deformation to plastic deformation. In the second turn, it goes from plastic deformation to elastic deformation. However, the elastic deformation mechanism of these two turns was not the same. The first was the elastic deformation of porous Cu, while the second was the elastic deformation of dense Cu. Because in the plastic deformation stage, the cell-walls of porous Cu collapse and fill the hole, causing the stress to continue to rise. For porous Cu which was particularly low in contents such as 10% and 20%, their stress-strain curves do not even show a second turn. In other words, these porous Cu samples were still in the plastic deformation stage. Due to their high strength, the tonnage limit of the instrument has been exceeded, resulting in the end of the test. For intermediate contents (i.e. 30–50%), the elastic deformation test ends before their second turn were fully turned into dense Cu, also because the strength at the end of the instrument has reached the tonnage limit.

Based on the above analysis, the elastic modulus and yield strength of the porous Cu were obtained from the first turn of the stress-strain curves, as shown in Table 2. Where, the symbols E and σy stand for elastic modulus and yield strength, respectively. For the elastic modulus, it was the slope of the line at the initial stage of the stress-strain curve but the sample was deducted to indicate uneven line segments. Since there were no obvious yield points, the stress corresponding to the elastic limit residual deformation of 0.2% was taken as the yield strength, as reported as in previous works32,33,34.

It can be seen that the elastic modulus and yield strength of porous Cu decreased with the increase of the space holder content (i.e. porosity), of which this trend was consistent with literature reports5,6. Meanwhile, it seems that the elastic modulus and yield strength of the porous Cu samples were decreased as the increase the space holder size in more cases. For the relative average deviation, it can be seen that the relative average deviation of all porous Cu contents was more than 1% for the elastic modulus (i.e. RE), which indicates that the space size has a significant effect on the elastic modulus of porous Cu. In particular, the elastic modulus of porous Cu decreases with the increase of pore size except 70%. For yield strength (i.e. Rσy), all but 30% content of porous Cu have a relative average deviation of more than 1%. Among them, the yield strength of porous Cu with content 10, 40–60% decreased significantly with the increase of space holder size, and the yield strength of porous Cu with spacer content 20, 70–80% increased significantly with the increase of space holder size.

Combined with the relative average deviation of porosity in Table 1, only porous Cu with a space holder content of 30% shows two results that the mechanical properties (elastic modulus and yield strength) change in the opposite direction with the change of porosity. In the remaining contents, some mechanical properties decrease with decreasing porosity (10% and 40%), some mechanical properties change inconsistently (20%, 60% and 80%), and some mechanical properties decrease (50%) or increase (70%) when the porosity was equal. However, except for 30%, the porosity of the remaining porous Cu decreases or remains unchanged with the increase of space holder size. These results indicate that the effect of space holder size on the porosity and mechanical properties of porous Cu was more complex than that of content.

Since the densification stress and its strain cannot be directly obtained from the stress-strain curve, precise identification of densification strain was difficult for metallic foams because of the obscure transformation19. Alternatively, the strategy of energy absorption efficiency-stress curve combined with stress-strain curve was used in our previous works14,15. The energy absorption efficiency refers to the ratio of absorbed energy to the corresponding stress, which was used to determine the best working state of foam energy absorption. If the energy absorption efficiency-stress curve has a stress peak, the stress corresponding to the peak was the densification strain. Again, the strain corresponding to the densification stress on the stress-strain curve was the densification strain. The formula for calculating the energy absorption efficiency was as follows:

where, ηEbe represents energy absorption efficiency, εm represents arbitrary strain, σm represents stress corresponding to εm, σ(ε) represents the stress relative to ε strain, ε represents strain. Figure 10 shows the energy absorption efficiency-compressive stress curves of the present porous Cu samples based on the above formula. We found that the energy absorption efficiency increases monotonically with the increase of stress when the spacer content was between 10 and 50% whenever the small or large size space holder particles used. However, the energy absorption efficiency increases first and then decreases with the increase of stress (i.e. peak value) since the spacer content over 60%. In other words, the porous Cu samples with spacer content between 60 and 80% were fractured during compression deformation.

Figure 11 shows the digital images of the longitudinal cutting samples at the end of the compression test. It can be clearly seen that there were a lot of surface fractures on the porous Cu samples with space holder content between 60 and 80%. This indicates that the cell-walls of these porous Cu samples had completely collapsed. For 50%, although there were many gaps in the surface, these gaps were not caused by fractures, but by the closure of the pores. With the decrease of space holder content, the decrease of pores leads to fewer and fewer cracks on the surface of porous Cu samples until it was difficult to see at low content such as 10%. Therefore, we only need to calculate the stress corresponding to the energy absorption efficiency-stress peak of porous Cu samples with space holder content between 60 and 80% and the densification strain corresponding to the stress on the stress-strain curve.

The calculated densification stress and its strain of the present porous Cu samples based on the above curves was shown in Table 3. The symbols σD and εD stand for densification stress and densification strain, respectively. It can be clearly seen that the densification stress and its strain decreased as the increase of spacer content whenever for the space holder size of 1.7–2 mm or 2–3 mm used. For the effect of spacer size, the densification stress and its strain of LSH-Porous Cu were larger than those of the corresponded SSH-Porous Cu for the spacer contents of 60% and 70% regardless of 80%, where the densification stress increased as the increase of space holder size while the densification strain of the two was equal. In other words, the space holder size has an effect on the densification stress and its strain of porous Cu, but it was just not regular as the spacer content. It can also be found that the densification stress of 60% was much higher than the latter two space holder contents whenever for the SSH-Porous Cu or LSH-Porous Cu. This may be related to the degree of pore connectivity. At space holder content 60%, porous Cu formed more closed-cell structure, and at 70%, more open-cell structure. Both the edge and surface of the closed-cell structure will bear the load, while the open-cell structure was the edge of the pores.

It also showed that the densification strain decreases with the increase of porosity, that is, the two have an inverted relationship. For this result, porous Cu with space holder content ranging from 50 to 80% were used as observation objects. Their cross-section morphology under 50% or 60% compressive strain was shown in Fig. 12. Among them, for porous Cu with 50% space holder content and 60% (for space holder size: 2–3 mm), the photo shows the cross-section morphology at 60% compression strain, and the rest of the porous Cu was 50% compression strain. For the porous Cu with 60–80% space holder content, the selected compression strains were all higher than their densification strains. The purpose was to observe the deformation characteristics of porous Cu samples after the densification strain. It can ben see that no cracks were observed in their cross sections for the porous Cu with 50% space holder content even at 60% strain (Fig. 12a and e). The observed gaps were left by macropores in the process of compression and densification. The closing of the macropores will improve the resistance of the Cu matrix to external forces, so that the sample was not fully dense when the press reaches the maximum tonnage. As a result, there was no densification strain for these porous Cu.

On the other hand, the failure of the samples cannot be observed from the cross section, although the selected strains all exceed their densification strains (Fig. 12b-d and f-h). Moreover, the macropores were not fully closed to form gaps. Therefore, as the strain increases, the fractured cell-walls will continue to fill the pores. In this process, as the pores were filled, the sample formed stronger resistance, so the stress-strain curve showed that the stress continued to rise with the increase of strain. With the increase of porosity, the number of pores in the sample also increases, and the space that can be filled was larger. Although the stress plateau of high porosity porous Cu was longer, the strength was lower, and thus the densification strain was smaller. For the porous Cu with the low porosity, the stress plateau was shorter, the strength was higher, and thus the densification strain was higher. That is to say, high porosity does not necessarily result in longer densification strain, but also requires high strength. Further, we take porous Cu with 80% content as an example, as shown in Fig. 13. They show the macroscopic morphology of porous Cu at 60% and 80% as well as initial strain cross sections. Compared with the morphology in Fig. 12d and h, the collapsed cell-walls continue to fill the pores, making the Cu matrix denser and producing stronger resistance, so the stress on the stress-strain curve shows that the stress exceeds the densification strain and still continues to rise. This phenomenon was also the plastic characteristic of SHT porous Cu with a solid skeleton4,5,7,9,12,18,35.

Energy absorption capacity was an important functional property of metal foams36. The energy absorption capacity was defined as the energy consumed when the foams are compressed to a certain strain, and corresponds to the enclosed region between the stress-strain curve and the strain axis37,38,39. The energy absorption capacity increases with the increase of strain, but reaches the maximum value at the densification strain. This value was the energy density of the porous metal, expressed in units per unit volume, which can be expressed as the following formula:

where, W represents energy density per unit volume. It was defined as the area under the stress-strain curve obtained prior to the onset of densification strain. For the porous Cu with space holder content between 60 and 80%, the energy density of them was calculated and shown in Table 4.

It can be seen that the energy density of the porous Cu decreased as the increase of space holder content (i.e. porosity) whenever for the SSH-Porous Cu and LSH-Porous Cu. As for the particle size of space holder, the energy density of LSH-Porous Cu was higher than that of SSH-Porous Cu for the contents 60% and 70% while the former was low than the latter for the content 80%. That is to say, the space holder size has an effect on the energy density of porous Cu, but it does not show regularity when compared with the space holder content. Another indicator of the energy absorption capacity of metal foam was the ideal energy absorption efficiency, which was the ratio of the energy absorbed by the actual foam material at any strain during the compression process to the energy absorption of the ideal foam material at the same strain, that is, the ratio of the area enclosed by the stress-strain curve to the rectangular area under any strain, which was used to reflect the proximity between the real material and the ideal energy-absorbing material. The ideal energy absorption efficiency can be used to evaluate the energy absorption performance of materials. The formula for calculating the ideal energy absorption efficiency was as follows:

where, ηIebe represents the ideal energy absorption efficiency. The energy absorption efficiency-compressive stress curve of the porous Cu based on the above formula was shown as in Fig. 14. It can be seen that the ideal energy absorption efficiency also has a peak value, and the stress corresponding to the peak value was the optimal working stress of the porous material.

The peak value of ideal energy absorption efficiency and corresponding stress (i.e. plateau stress, σpl) of the porous Cu with volume content of spacer content ranging 60–80% were shown in Table 5. It can be seen that the ideal energy absorption efficiency was much higher than the energy absorption efficiency, this is because the denominator of the former formula was much smaller than that of the latter. The plateau stress was also between the yield strength and the densification strength. On the other hand, the ideal energy absorption efficiency increased as the increase of space holder content, while the plateau stress decreased. As for the space holder size, it has an effect on both properties but no regularity.

To study the relationship between the property and the pore factors, the main is to study that between the property and the porosity40. According to the Gibson-Ashby theory27, the relative elastic modulus of open porous metals was directly proportional to the square of relative density, and the relative plateau strength (often replaced by the yield strength) was directly proportional to the 1.5 square of relative density (i.e. Standard G-A model). However, according to our previous researches, we found that the power exponential relations were used more in reality because of a complex and changeable internal pore structure in the actual porous metals (i.e. Modified G-A model)15,41. Figure 15 shows the relationships between the relative elastic modulus & yield strength and relative density of porous Cu samples based on the standard and modified G-A models. Among them, Es (= 119 GPa) and σys (= 80 MPa) represent the elastic modulus and yield strength of the bulk pure Cu, respectively; E/Es and σy/σys represent relative elastic modulus & yield strength, respectively; 1-P represents the relative density, dimensionless.

The fitting degree of the black line (R2 = 0.91284) was higher than that of the red line (R2 = 91127) for the prediction of elastic modulus of SSH-Porous Cu in Fig. 15 (a), while the fitting degree of the red line (R2 = 1) was higher than that of the black line (R2 = 97845) for the prediction of elastic modulus of LSH-Porous Cu in Fig. 15 (b). However, we use the red dotted line instead of the solid line because we found that the two fitted curves coincide exactly. Moreover, exponential fitting was also a square relation and its fit was equal to 1 in particular. The results indicated that the classical G-A theory has good applicability in predicting elastic modulus of the present porous Cu when compared with a recent work about quantitative relationships between cellular structure parameters and the elastic modulus of aluminum foam42. For the yield strength, it was found that the fitting degree of the red lines (R2 = 99806 and 9667) was higher than that of the black lines (R2 = 95649 and 78937) in Fig. 15 (c) and (d). The results indicated that an indexation adjustment of the classical G-A theory was needed in predicting yield strength for the present porous Cu.

Thus, the relations between the relative elastic modulus & yield strength and relative density of the present porous Cu samples can be shown as the follows:

The relative average deviations for the coefficient and index between formula 6 and 7 were 14.28% and zero, while they were 17.95% and 5.08% for formula 8 and 9. This indicated that the space holder size has no effect on the square relation between the relative elastic modulus and the relative density of porous Cu, but it affects the coefficient of the correlation. For yield strength, the space holder size not only affects the index of fitting formula but also the coefficient.

By submitting formula 1 into formulas 6 and 8, and formula 2 into formulas 7 and 9, respectively, the following formulas can be obtained:

According to the above four formulas, the correlations between the relative elastic modulus & yield strength and relative density of the present porous Cu fabricated using two different space holder sizes were established as E/Es=C(ax-b)2 and σy/σys = C(b-ax)n, respectively. Where, the italic characters of a, b and C stand for constant and n stands for exponent. Thus, the source prediction of the elastic modulus and yield strength of the present porous Cu was realized. However, we cannot be limited to this, the more uniform space holder size should be chosen in the future to continue to study the pore structure and mechanical properties of porous Cu.

Conclusions

In this paper, the effects of the space holder size on the pore structure and mechanical properties of porous Cu were studied by using high purity Cu powder as raw material and 1.7–2 mm & 2–3 mm spherical carbamide as space holder with volume content in the range of 10–80%. The main conclusions that can be drawn as follows:

-

(1)

The effect of space holder size on the porosity of porous Cu was mostly negative correlation but there were also positive correlation and no correlation. The pore size of porous Cu increases with the increase of space holder size, but not including 80% content. Because of this content, the smaller the space holder size, the more conducive to the connectivity of the internal pores of porous Cu, thus forming larger pores.

-

(2)

The compressive stress-strain curves of porous Cu were smooth, showing the deformation characteristics of plastic porous materials. The elastic modulus and yield strength of porous Cu decreased with the increase of space holder content. With the increase of space holder size, the elastic modulus of porous Cu mostly decreases, but the yield strength was irregular.

-

(3)

The densification stress & strain of 60–80% porous Cu decrease with the increase of space holder content, while change irregularly with the increase of space holder size. The higher the porosity of porous Cu, the lower the mechanical properties and the densification strain starts earlier but ends later.

-

(4)

The energy density of porous Cu changes irregularly with the increase of space holder size. The ideal energy absorption efficiency of porous Cu was much higher than its energy absorption efficiency and the plateau stress was between yield strength and densification stress. The ideal energy absorption efficiency and plateau stress of porous Cu change irregularly with the increase of space holder size.

-

(5)

The relationship between the relative elastic modulus and relative density of porous Cu can be well described by the classical G-A model, while the relationship between the relative yield strength and relative density of porous Cu was more suitable to describe by the power exponent. They were E/Es=C(ax-b)2 and σy/σys = C(b-ax)n, respectively. It was found that the space holder size has influence on both the fitting formulas of elastic modulus and yield strength of porous Cu, except the index in the fitting formulas of elastic modulus.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Guo, G. D. et al. Refined Pore structure design and surface modification of 3D porous copper achieving highly stable Dendrite-Free Lithium-Metal Anode. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2402490. (2024).

Girichandran, N., Saedy, S. & Kortlever, R. Electrochemical CO2 reduction on a copper foam electrode at elevated pressures. Chem. Eng. J. 487, 150478 (2024).

Hu, C. Z. et al. Copper foam reinforced polymer-based phase change material composites for more efficient thermal management of lithium-ion batteries. J. Energy Storage. 73, 108918 (2023).

Shirjang, E. & Akbarpour, M. R. Influence of severe plastic deformation of Cu powder and space holder content on microstructure, thermal and mechanical properties of copper foams fabricated by lost carbonate sintering method. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 26, 5437–5449 (2023).

Ray, S., Jana, P., Kar, S. K. & Roy, S. Influence of monomodal K2CO3 and bimodal K2CO3 + NaCl as space holders on microstructure and mechanical properties of porous copper. Mater. Sci. Eng. A. 862, 144516 (2023).

Jana, P. et al. Study of the elastic properties of porous copper fabricated via the lost carbonate sintering process. Mater. Sci. Eng. A. 836, 142713 (2022).

Hong, K. et al. Comparison of morphology and compressive deformation behavior of copper foams manufactured via freeze-casting and space-holder methods. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 15, 6855–6865 (2021).

Mosalagae, M., Renteria, C. M. B., Elbadawi, M., Shbeh, M. & Goodall, R. Structural characterisation of porous copper sheets fabricated by lost carbonate sintering applied to tape casting. Mater. Charact. 159, 110009 (2020).

Zhao, Y. Y., Fung, T., Zhang, L. P. & Zhang, F. L. Lost carbonate sintering process for manufacturing metal foams. Scripta Mater. 52, 295–298 (2005).

Bram, M., Stiller, C., Buchkremer, H. P., Stver, D. & Baur, H. High-porosity Titanium, Stainless Steel, and Superalloy Parts. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2, 196–199 (2000).

Sun, Y. & FOR MANUFACTURING Al FOAMS. Scripta Mater. 44, 105–110. (2001).

Wang, Q. Z., Cui, C. X., Liu, S. J. & Zhao, L. C. Open-celled porous Cu prepared by replication of NaCl space-holders. Mater. Sci. Eng. A. 527, 1275–1278 (2010).

Zhao, B. et al. Effect of micropores on the microstructure and mechanical properties of porous Cu-Sn-Ti composites. Mater. Sci. Eng. A. 730, 345–354 (2018).

Xiao, J., Li, Y., Liu, J. M. & Zhao, Q. L. Fabrication and characterization of porous copper with Ultrahigh Porosity. Metals 12, 1263–1269 (2022).

Xiao, J., He, Y., Ma, W., Yue, Y. & Qiu, G. Effects of the space holder shape on the Pore structure and Mechanical properties of Porous Cu with a wide porosity range. Materials 17, 3008 (2024).

Zou, L. et al. Fabrication and mechanical behavior of porous Cu via chemical de-alloying of Cu25Fe75 alloys. J. Alloys Compd. 689, 6–14 (2016).

Parvanian, A. M., Saadatfar, M., Panjepour, M., Kingston, A. & Sheppard, A. P. The effects of manufacturing parameters on geometrical and mechanical properties of copper foams produced by space holder technique. Mater. Design. 53, 681–690 (2014).

Parvanian, A. M. & Panjepour, M. Mechanical behavior improvement of open-pore copper foams synthesized through space holder technique. Mater. Design. 49, 834–841 (2013).

Guo, C. et al. Compressive properties and energy absorption of aluminum composite foams reinforced by in-situ generated MgAl2O4 whiskers. Mater. Sci. Eng. A. 645, 1–7 (2015).

Hajizadeh, M., Yazdani, M., Vesali, S., Khodarahmi, H. & Mostofi, T. M. An experimental investigation into the quasi-static compression behavior of open-cell aluminum foams focusing on controlling the space holder particle size. J. Manuf. Process. 70, 193–204 (2021).

Tejeda-Ochoa, A., Rivera-Vicuna, K. G., Ledezma-Sillas, J. E., Herrera-Ramirez, J. M. & Carreno-Gallardo, C. The effect of space holder size on the mechanical properties of porous titanium. Microsc. Microanal. 29, 1459–1460 (2023).

Luo, H. J., Zhao, J. H., Du, H., Yin, W. & Qu, Y. Effect of mg powder’s particle size on structure and Mechanical properties of Ti Foam synthesized by space holder technique. Materials 15, 8863 (2022).

Sharma, M., Modi, O. P. & Kumar, P. Synthesis and characterization of copper foams through a powder metallurgy route using a compressible and lubricant space-holder material. Int. J. Minerals Metall. Mater. 25, 902–912 (2018).

Bolzoni, L., Carson, J. K. & Yang, F. J. A. M. Combinatorial structural-analytical models for the prediction of the mechanical behaviour of isotropic porous pure metals. 207, 116664. (2021).

B, Y. H. X. A. A, H.J.J. A universal scaling relationship between the strength and Young’s modulus of dealloyed porous Fe0.80Cr0.20. Acta Mater. 186, 105–115 (2020).

Institution, B. S. Mechanical testing of metals-Ductility testing-Compression test for porous and cellular metals, Geneva, Switzerland, (2011).

Gibson, L. J. & Ashby, M. F. Cellular Solids: Structure and Properties (Cambridge University Press, 1999).

Xiao, J., Cui, H., Qiu, G. B., Yang, Y. & Lyu, X. W. Investigation on relationship between porosity and spacer content of titanium foams. Mater. Des. 88, 132–137 (2015).

Arifvianto, B., Leeflang, M. A. & Zhou, J. Characterization of the porous structures of the green body and sintered biomedical titanium scaffolds with micro-computed tomography. Mater. Charact. 121, 48–60 (2016).

Xiao, J. et al. The application of the model equation method in the preparation of porous copper by using needlelike and spherical carbamide as a space holder. Powder Metall. 66, 365–376 (2023).

Yang, D. et al. Preparation principle and compression properties of cellular Mg-Al-Zn alloy foams fabricated by the gas release reaction powder metallurgy approach. J. Alloys Compd. 857, 158112 (2021).

Hakamada, M. et al. Density dependence of the compressive properties of porous copper over a wide density range. Acta Mater. 55, 2291–2299 (2007).

Du, H., Cui, C. Y., Liu, H. S., Song, G. H. & Xiong, T. Y. Improvement on compressive properties of lotus-type porous copper by a nickel coating on pore walls. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 37, 114–122 (2020).

Sutygina, A., Betke, U. & Scheffler, M. Hierarchical-porous copper foams by a combination of Sponge replication and Freezing Techniques. Adv. Eng. Mater. 24, 2001516 (2021).

Wang, Q. Z., Lu, D. M., Cui, C. X. & Liang, L. M. Compressive behaviors and energy-absorption properties of an open-celled porous Cu fabricated by replication of NaCl space-holders. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 211, 363–367 (2011).

Ashby, M. F. et al. Metal Foams: A Design Guide (Elsevier, 2000).

Liu, J. et al. Adjusting compressive properties of open-cell Mg-Gd-Zn foams by variation of Gd content. Mater. Sci. Eng. A. 820, 141562 (2021).

Liu, J., Zhang, L., Liu, S., Han, Z. & Dong, Z. Effect of Si content on microstructure and compressive properties of open cell mg composite foams reinforced by in-situ Mg2Si compounds. Mater. Charact. 159. (2020).

Cao, M. et al. Construction and deformation behavior of metal foam based on a 3D-Voronoi model with real pore structure. Mater. Design. 238, 112729 (2024).

Liu, P. S. & Ma, X. M. Property relations based on the octahedral structure model with body-centered cubic mode for porous metal foams. Mater. Design. 188, 108413 (2020).

Xiao, J., Liu, Y. N., Li, Y. & Qiu, G. B. The application of model equation method in preparation of titanium foams. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 13, 121–127 (2021).

Zhao, W. et al. Volkova, O. quantitative relationships between cellular structure parameters and the elastic modulus of aluminum foam. Mater. Sci. Eng. A. 868, 144713 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [no. 52074052] and by the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangxi Province [no. 20232BAB214041].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

He Yanping carried out the analytical test and wrote the manuscript. Xie Shubao and Tan Ruicheng responsible for material preparation. Xiao Jian and Qiu Guibao revise the paper and supervised the findings of this work. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yanping, H., Jian, X., Shubao, X. et al. Effects of the space holder size on the pore structure and mechanical properties of porous Cu with a wide porosity range. Sci Rep 15, 11072 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87570-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87570-y