Abstract

The performance assessment of slopes during various disturbances is important to ensure the safe service of slopes. Due to the four characteristics of slope engineering, it is difficult for existing resilience evaluation models to accurately reflect slope performance. To address this problem, a resilience evaluation model applicable to slopes was developed in this study. In this model, a typical slope performance curve is proposed according to the characteristics of slope engineering and the calculation formula of slope resilience metric is derived. In order to facilitate engineering application, this study proposes a slope resilience assessment framework with the evaluation model as the core. In the resilience assessment framework, a multi-indicator system for slope performance was established to cover the slope components, and the CRITIC theory was used to combine the subjective and objective weights for each indicator. Finally, the proposed slope resilience assessment framework was applied to a slope case under the influence of continuous excavation and rainfall. The results show that the proposed resilience assessment framework can more accurately reflect the performance variations of slopes during disturbance and recovery processes than the existing model, and the resilience metric is 23.4% higher than that of the existing model. This study was the first attempt to establish a resilience assessment framework applicable to slopes, which informs subsequent research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Slopes play a vital role in many fields such as highways, railways, hydraulic facilities and urban construction in mountainous areas. With the rapid development of infrastructure construction, a large number of slope systems have been constructed and put into service. However, the construction and service of these slopes are inevitably affected by various human activities or natural disasters, such as construction of excavation1, external loads2,3, earthquakes4,5,6, rainfall7,8, etc., and these unfavourable influences can be generally called disturbances. Under the influence of various disturbances, the stability of the slope will be reduced, which will not only threaten the life and property safety of nearby residents, but also may produce various secondary disasters. Therefore, it is necessary to evaluate the performance of slopes under various disturbances during the whole life cycle.

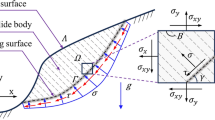

Many researchers have studied the performance evaluation and risk assessment of slope projects. Most of the studies on the slope performance focus on stability, which is described by the factor of safety. The factor of safety is defined as the ratio of the resisting force to the sliding force and is calculated using the limit equilibrium method based on simplified mechanical models9,10. In contrast, in the assessment of slope performance considering uncertainty, the failure probability instead of the factor of safety is used to describe the slope performance due to the application of probability theory11,12. Some studies have combined the strength reduction method with numerical simulations13,14,15. The mechanical parameters of the soil are proportionally reduced, and then the critical state of the slope is determined by the sudden change of slope displacement. The strength reduction factor at the critical state is then used to assess the slope performance. However, all of the traditional slope performance assessment methods mentioned above can only statically assess the slope performance at a certain moment, failing to consider the effects of dynamic processes such as excavation, earthquakes, rainfall, and so on. Taking the factor of safety as an example, the factor of safety for slopes in dynamic processes can only be calculated with some simplifications. Besides, it cannot reflect some changes in the slope performance during the dynamic process. As a matter of fact, slope projects encounter multiple disturbances during construction and service. The performance of slopes changes dynamically at different stages, such as pre-disturbance, disturbance, evolution and reinforcement. Hence, the concept of resilience needs to be introduced into slope performance assessment, as resilience can describe the change of performance with time and achieve a full life-cycle slope performance assessment.

Since the concept of resilience was introduced into the engineering field, a number of researchers have studied the resilience of different kinds of engineering based on their performance curves. Bruneau et al. used performance curves of infrastructure systems to describe the resilience of communities during earthquakes16. Tierney and Bruneau proposed a resilience evaluation model based on the infrastructure performance curves, defining the resilience metric of an infrastructure as the loss area of the performance curve caused by disturbances17. In contrast, Attoh-okine et al. proposed a new definition method for resilience metrics that describes resilience in terms of the ratio of the integral of the disturbed performance curve to the integral of the initial performance metric18. This definition method has been widely used in recent studies. Huang and Zhang followed this resilience metric definition and proposed a resilience evaluation model applicable to tunnel structures by considering the natural decrease of the tunnel structure’s performance19. Subsequently, Lin et al. proposed an analytical model for the resilience of shield tunnel lining considering multistage disturbance for shield tunnels, which are often subject to several disturbances20. Chen et al. proposed a resilience evaluation model applicable to metro systems with respect to the interactions of various parts of the metro system21. This model links the individual structural resilience to the overall resilience by combining graph theory and resilience concept. Meanwhile, Han et al. proposed a resilience assessment framework based on the cooperative response mechanism between the existing underground structure and the strata22. Qiu et al. developed a resilience assessment framework with adaptability as the core focus for the characteristics of key components in underground stations23. In summary, with the gradual development of the researches on engineering resilience, the definitions of resilience metrics have tended to be unified. However, different types of engineering concern different properties, suffer different disturbances, and have different responses under the disturbances. Therefore, the major research direction at present is to develop specific resilience assessment models according to the characteristics of different types of engineering.

Currently, there are numerous researches on resilience assessment in the fields of tunnels, underground spaces, metro systems, etc., and resilience evaluation models corresponding to different types of engineering have been developed. However, the resilience evaluation models of other engineering cannot be applied to slopes due to their characteristics in many aspects, such as construction process, components, performance evolution, and so on. The characteristics of slope engineering are summarised as follows:

(1) In order to meet the functional requirements, slopes are excavated and then supported stage by stage during the construction process. As a result, the slope undergoes several cycles of disturbance-recovery, which is not represented in the existing resilience evaluation models.

(2) After the reinforcement is completed, the slope performance may not necessarily remain constant, but may also be increased or decreased. In other words, there is an evolution stage not only after the disturbed stage, but also after the recovery stage.

(3) Slope engineering usually consists of three components: the slope body, the supporting structure, and the nearby buildings. In each component, there are several indicators that can represent the performance of slope. Therefore, the existing resilience evaluation model with single performance indicator is not applicable to slope engineering.

(4) The disturbance duration of slopes is short, and the natural degradation of the performance curve is not obvious. While the natural degradation is involved in the calculation of resilience metrics based on existing models.

Until now, no resilience evaluation model suitable for slopes has been developed according to the above characteristics. Only a few researchers have attempted to introduce resilience theory into slope investigations. Das et al. attempted to introduce the concept of resilience into the slope stability research, but did not propose a slope resilience metric based on the performance curves24. He et al. used a simplified performance curve to describe the variation of slope performance under seismic effects25. However, the schematic was only discussed and no resilience evaluation model was developed based on it.

In this study, a resilience evaluation model for slope engineering is developed, and the main contents are as follows. Firstly, the connotation of slope resilience is explained from the resilience concept, combined with the performance curve of slope engineering. Next, the resilience evaluation model suitable for slopes is developed according to the characteristics of slope engineering. Further, a slope resilience assessment framework containing multiple steps is proposed with the evaluation model as the core. The steps include the establishment of a multilevel performance indicator system involving three components of the slope, the calculation of the slope composite performance Q using the subjective-objective combined weights, and the calculation of the slope system resilience metrics based on the composite performance curves. Finally, the proposed assessment framework is applied to a slope project case which is disturbed by excavation and rainfall.

Resilience evaluation model for slopes

Definition of slope resilience

The resilience evaluation of slope systems presupposes a precise definition of slope resilience and description of the several properties it contains. Since the concept of resilience has been developed and extended to various research fields such as economic management, biology, environment, engineering, etc., the meaning of resilience varies from one research field to another. In most studies related to resilience in the engineering field, resilience is often considered to include five properties, which are robustness, redundancy, rapidity, adaptability, and resourcefulness19,20,21,22,23. The first three properties are related to engineering technology, while adaptability and resourcefulness are mainly related to management decisions for disaster response. The meanings of these five properties are as follows:

-

- Robustness: the ability to resist and withstand disturbances.

-

- Redundancy: The ability to accommodate a disturbance and stop damage from spreading or further damage.

-

- Rapidity: The ability to recover quickly after damage has occurred.

-

- Adaptability: The ability to learn from previous disturbances and improve its adaptive capacity to cope with the following disturbance.

-

- Resourcefulness: The ability to choose the optimal decision with appropriate recovery time and lower recovery costs.

Thus, the connotation of slope resilience should contain three properties including robustness, redundancy, and rapidity18. Since slope engineering is different from tunnel and underground space engineering, the definition of three properties in slope resilience is given in this study considering the failure mode and construction mode of slope engineering. For slopes, robustness refers to the ability to resist the effects of disasters or block the interference of disasters, which can be evaluated by the performance decrease of the slope system during disasters. Slope redundancy refers to the ability to prevent damage propagation and expansion under the influence of a disaster, which can be evaluated by the threshold value of the performance indicators corresponding to the overall failure of the slope. The rapidity of the slope refers to the ability of the slope performance to recover quickly after reinforcement on the one hand, and to the ability of the slope performance to recover during the evolution stage without reinforcement on the other hand. This property can be evaluated by the increase rate of performance after reinforcement as well as the increase rate of performance without reinforcement. In summary, slope systems with higher resilience should have the ability to withstand the effects of disasters, be less prone to uninterruptible overall failure under the influence of a disaster, and be able to rapidly recover their performance after a disaster.

In addition, two other properties related to management decisions can be improved by the slope resilience assessment framework proposed in this study. Using the proposed framework to assess the resilience of a slope during previous disasters can improve the adaptability of that slope to cope with future disasters and help decision makers to choose the optimal recovery solution. Therefore, the resilience assessment framework not only assesses the robustness, redundancy, and rapidity of a slope, but also effectively improves the adaptability and resourcefulness of a slope when applied by decision makers.

Resilience evaluation model of slopes

In the analysis of engineering resilience, resilience metrics are determined through a resilience evaluation model. Therefore, the resilience evaluation model applicable to slopes is the core part of the resilience assessment framework. So far, researchers have developed a variety of resilience evaluation models for different types of engineering17,18,19,20,26. These resilience evaluation models are all based on the performance curves of the engineering under the influence of disturbances, and the resilience metric is calculated from several areas of the curves.

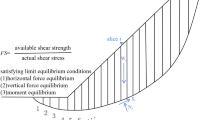

As previously stated in the Introduction, the four characteristics of slope systems render existing resilience evaluation models inapplicable to slopes. Accordingly, a resilience evaluation model applicable to slopes was developed in this study, with consideration of the aforementioned four characteristics of slope systems, as illustrated in Fig. 1.

The first characteristic of slopes is that they undergo multiple Disturbance-Recovery cycles during construction. The construction of a slope project involves the gradual excavation of the natural slope and the reinforcement after each excavation. In order to reflect this characteristic, the performance curve of the slope is divided into three types: the disturbed stage, the evolution stage, and the recovery stage, which are represented by the red, blue, and green parts, respectively, in Fig. 1. In the performance curves, a disturbed stage and an evolution stage constitute one disturbance. Similarly, a recovery stage and an evolution stage constitute one recovery. Disturbances and recoveries can be arranged on the timeline according to the specific project, and thus can reflect the characteristic of slopes undergoing multiple disturbance-recovery cycles. When the recovery stage is arranged at the top, it can represent the pre-reinforcement of the slope. In case of disturbances occurring consecutively without restoration in between, the performance curve is similar to that proposed by Lin et al. and can reflect the case where the project is subjected to several continuous disturbances20. It should be noted that the disturbances in Fig. 1 can represent different hazards suffered by the slopes, including construction excavation, earthquake, blast impact, rainwater erosion, and so on.

The second characteristic of slopes is that slope performance may increase or decrease after the reinforcement is completed. Since slope failure is progressive, reinforcement of slopes does not necessarily interrupt the gradual failure process, and performance may continue to decrease after reinforcement is completed. In addition, variations of the reinforcement itself can lead to changes in slope performance after the recovery stage. For example, the hydration reaction leads to increased strength of the concrete facings on the slope surface, and the relative movement of the prestressing anchor components leads to a loss of prestress after the tension. To reflect this characteristic, each recovery stage is immediately followed by an evolution stage in the slope performance curves proposed in this study, as shown in Fig. 1. According to the specific situation, the slope performance could increase, decrease or remain unchanged during the evolution stage. It is worth noting that the evolution stage is often ignored when the trend of performance variation in the evolution stage is the same as that in the recovery stage, as in several existing resilience models17,19,26.

The third characteristic of slopes is that slope engineering contains three components: the slope body, the supporting structures, and the nearby buildings, while each component has a variety of indicators that can represent the slope’s performance. In other words, the resilience evaluation model based on single performance indicator is not applicable to slopes. Considering this characteristic, a multi-indicator system covering the three components of the slope is established, and the performance curve in Fig. 1 is obtained by combining the performance indicators.

The fourth characteristic of slopes is that natural degradation curves are difficult to obtain. Given the typically short duration of disturbances affecting slopes, there is no significant degradation of slope performance during this period. Considering this characteristic, the performance indicator at the beginning of disaster \(\:{Q}_{ini}\) is used as the best performance of the slope. Therefore, the slope resilience metric \(\:{Re}_{s}\) in the developed evaluation model is defined by Eq. (1):

where \(\:{q}_{i}\left(t\right)\) denotes the ith stage of the performance curve; \(\:{Q}_{ini}\) denotes the slope performance at the beginning of disaster; \(\:{t}_{0}\),\(\:\:{t}_{n}\), \(\:{t}_{i}\) denotes different moments, as shown in Fig. 2.

The three properties of slope resilience defined in Sect. 2.1 are also reflected in the developed slope resilience evaluation model, as shown in Fig. 1. Robustness is evaluated by the loss of slope performance caused by the disturbance, and the smaller performance loss indicates the better slope robustness. Redundancy is evaluated by the performance threshold corresponding to the overall damage of the slope, i.e., the purple line in Fig. 1. The lower threshold value indicates that the slope is less susceptible to overall failure, i.e., the better the redundancy. Rapidity is evaluated by the improvement of performance after reinforcement, and the more performance improvement indicates the better rapidity of the slope.

Development of resilience assessment framework for slopes

In Sect. 2, the resilience evaluation model for slopes has been proposed according to the characteristics of slopes. In order to conveniently apply the model to practical projects, this study proposes a multi-indicator slope resilience assessment framework consisting of five parts with the resilience assessment model as the core, as shown in Fig. 3. The specific contents of each part of the resilience assessment framework are as follows:

(1) Information collection and response analysis: According to the specific project, collect information about the slope body, supporting structures and nearby buildings. Then based on the expertise of slope-supporting structure-neighbouring building interaction, the response of the slope under different conditions is analysed.

(2) Data collection scheme determination: for pre-disaster resilience analysis, determine a reasonable data collection scheme based on the slope response. For post-disaster resilience analysis, check whether the existing monitoring data meet the expected collection scheme.

(3) Establishment of performance indicator system: Based on the slope response, establish a slope performance indicator system covering three components: the slope body, the supporting structures, and the nearby buildings. According to the specific project, the indicator system can be adjusted under different disturbances or in different stages.

(4) Evaluation of composite performance Q: The composite performance Q is calculated by combining multiple performance indicators in the indicator system, which represents the slope’s performance during the disaster. The evaluation of composite performance Q consists of four steps: positivisation and normalisation of indicators; determination of combined weights; evaluation of weighted indicators; and calculation of composite performance Q.

(5) Calculation of the slope resilience metric \(\:{Re}_{s}\): After obtaining the composite performance curve, the resilience metric \(\:{Re}_{s}\) is calculated according to the slope resilience evaluation model proposed in this study.

In the above steps, the software tool used for data processing is MATLAB and the computational algorithms are MATLAB codes based on the formulas in the present section.

Performance indicator system of slopes

As explained in Sect. 2.2, slope engineering consists of three components: the slope body, the support structure, and the nearby buildings, and each of these components has a variety of indicators that can be used to represent the performance of the slope. It is therefore necessary to establish a multi-indicator system that covers each component of the slope and thus assesses the combined performance of the slope. In the present study, with reference to the slope monitoring items recommended by codes and relevant literatures on slope performance analysis, a slope performance indicator system containing 24 indicators was established, and the detailed definitions of each indicator are summarised in Table 1.

The 24 slope performance indicators can be divided into two categories: observable indicators and overall indicators. Observable indicators refer to the performance indicators that can be easily observed in actual projects, which are selected with reference to the necessary monitoring items listed in several standards27,28,29. Overall indicators are those that reflect the overall performance of the slope. They are selected with reference to the indicators describing slope performance in the relevant literature, such as the factor of safety in stability analysis and the probability of slope failure taking into account soil uncertainty. These overall indicators can reflect the performance of the slope at the stage of lack of observable data, but they require a long time to be obtained by professional researchers who have mastered numerical simulation techniques.

The established slope performance indicator system consists of four levels, as shown in Fig. 4. The first level is the composite performance indicator Q, which represents the performance covering the three components of the slope. The second level includes three indicators A, B, C, which represent the performance of the slope body, the supporting structures, and the nearby buildings, respectively. The third level includes the 18 specific performance indicators listed in Table 1, which are labelled as \(\:{a}_{i}(i=\text{1,2},\dots\:,12)\), \(\:{\text{b}}_{j}(j=\text{1,2},\dots\:,7)\), \(\:{\text{c}}_{k}(k=\text{1,2},\dots\:,5)\), according to the component they belong to. The fourth level indicators are the different monitoring points corresponding to a performance indicator, e.g. \(\:{\text{b}}_{1,m}\) represents the mth monitoring point for indicator \(\:{\text{b}}_{1}\).

It is important to note that the established performance indicator system is not unchangeable. Rather, the indicators should be supplemented and selected for application based on the information collection and response analysis results in Step 1 of the assessment framework. The performance indicators listed in Table 1 are more applicable to soil slopes. However, after selecting appropriate performance indicators based on expertise, the performance indicator system can be flexibly applied to soil and rock slopes, slopes subject to different disasters, slopes with different support structures, and slopes with or without the nearby buildings.

Positivisation and normalisation of indicators

After the performance indicator system has been established, the collected values for each indicator need to be positivised and normalised. Due to different physical meanings, not all performance indicator values are positively related to slope performance. Therefore, indicators can be classified into four types according to the relationship between their values and slope performance: positive indicators, negative indicators, single-point optimal indicators, and interval optimal indicators. For example, smaller displacement of the slope surface indicates better slope performance, which is a negative indicator, while the closer the anchor tension force is to the designed value indicates better slope performance, which is a single-point optimal indicator. The purpose of positivisation is to eliminate the influence of different indicator types, so that the value of each indicator is positively correlated with the slope performance. The positivisation processing formulas for each type of indicator is shown in Table 2.

The magnitudes of the performance indicators can differ significantly, making them not directly usable for analyses. In order to avoid the effect of indicator magnitude, normalisation of the indicators is also necessary after positivisation. In this study, the Z-score normalisation method as shown in Eq. (2) is applied. Compared with other normalisation methods, Z-score normalisation is simple to calculate and the normalised data is more consistent with normal distribution, which can meet the requirements of many statistical models.

Combined weights based on the CRITIC method

In the multi-indicator resilience assessment framework, due to the different contributions of each performance indicator to the composite slope performance, appropriate weights need to be assigned to each indicator. The weights can be categorised into three types: subjective weights, objective weights and combined weights. Since both subjective and objective weights have advantages, the CRITIC method proposed by Diakoulaki30 was used in this study to determine the weights of each indicator. The CRITIC method, known as ‘Criteria Importance Through Intercriteria Correlation’, is a commonly used method for importance analysis in the field of evaluation. The core of the method is to determine the importance of different types of data by considering the contrast intensity (represented by standard deviation) and the conflict (based on the correlations) between different types of data. For this study, the contrast intensity is the difference between the weight values of the indicators, while conflict is measured by the Pearson correlation coefficient between the different types of weights. If there is a high correlation between two types of weights, it indicates that they may reflect similar information and therefore their importance should be appropriately reduced to avoid overlapping information. The CRITIC method measures the conflict between different types of weights through the Pearson correlation coefficient, which assumes that the correlation between weights is linear. Therefore, the limitation of the CRITIC method is that it may ignore non-linear correlations between different types of weights. In this study, the CRITIC method reasonably combines subjective weights obtained by hierarchical analysis with objective weights obtained by entropy weight method and coefficient of variation method, which not only reflects the importance of experts on different indicators, but also ensures the objectivity of different indicators’ weights.

The analytic hierarchy process (AHP) determines the weights of the indicators through the subjective judgement of experts. In AHP, experts compare the importance between indicators through accumulated practical experience, and quantify the relative importance between indicators using the 1–5 scale method to construct a judgment matrix as shown in Eq. (3). In the judgment matrix, \(\:{a}_{ij}\) indicates the relative importance of the ith indicator to the jth indicator, and \(\:{a}_{ij}=1/{a}_{ji}\). In this study, the judgment matrix is constructed by several professors in the field of geotechnical engineering at Dalian University of Technology. After the judgment matrix was obtained, the eigenvector of the judgment matrix was determined and normalized to obtain the subjective weights of each indicator. The obtained subjective weights can be applied to this study after passing the consistency check. According to the engineering experience of experts, the more the indicator can reflect the slope performance, the larger the corresponding weight is, and vice versa, the smaller the weight is. The subjective weights of the second-level indicators obtained by AHP are labelled as \(\:{H}_{A}\), \(\:{H}_{B}\), \(\:{H}_{C}\), and the subjective weights of the third-level indicators are labelled as \(\:{H}_{a,i}(i=\text{1,2},\dots\:,9)\), \(\:{H}_{b,j}(j=\text{1,2},\dots\:,4)\), \(\:{H}_{c,k}(k=\text{1,2},\dots\:,5)\).

Unlike subjective methods, the entropy weight method (EWM) determines the weights based on the indicator data. In EWM, information entropy is used to measure the effective information provided by the indicator. The smaller the information entropy, the greater the dispersion of the indicator data, which means that the indicator is more important for slope performance. The objective weights of the second-level indicators obtained by EWM are labelled as \(\:{E}_{A}\), \(\:{E}_{B}\), \(\:{E}_{C}\), and those of the third-level indicators are labelled as \(\:{E}_{a,i}(i=\text{1,2},\dots\:,9)\), \(\:{E}_{b,j}(j=\text{1,2},\dots\:,4)\), \(\:{E}_{c,k}(k=\text{1,2},\dots\:,5)\).

The coefficient of variation method (CVM) is an objective method to determine the weights of slope indicators according to their variation degree. A large variation degree of an indicator represents that it is more important in slope performance and should be given a larger weight; conversely, a smaller weight should be given. The objective weights of the second-level indicators obtained by CVM are labelled as \(\:{V}_{A}\), \(\:{V}_{B}\), \(\:{V}_{C}\), and those of the third-level indicators are labelled as \(\:{V}_{a,i}(i=\text{1,2},\dots\:,9)\), \(\:{V}_{b,j}(j=\text{1,2},\dots\:,4)\), \(\:{V}_{c,k}(k=\text{1,2},\dots\:,5)\).

After determining the subjective weights and the two objective weights, the CRITIC theory was applied to quantify the percentage of each weight in the portfolio weights in terms of both the contrast intensity and the conflicting character. The calculation process of the combined weights is described below taking the nine third-level indicators \(\:{a}_{1}\) to \(\:{a}_{9}\) as an example. The three kinds of weights that have been determined are represented by vectors as \(\overset{\lower0.5em\hbox{$\smash{\scriptscriptstyle\rightharpoonup}$}} {H} = \left[ {H_{{a1}} ,~H_{{a2}} ,~ \ldots ,~H_{{a9}} } \right]\), \(\overset{\lower0.5em\hbox{$\smash{\scriptscriptstyle\rightharpoonup}$}} {E} = \left[ {E_{{a1}} ,~E_{{a2}} ,~ \ldots ,~E_{{a9}} } \right]\) and \(\overset{\lower0.5em\hbox{$\smash{\scriptscriptstyle\rightharpoonup}$}} {V} = \left[ {V_{{a1}} ,~V_{{a2}} ,~ \ldots ,~V_{{a9}} } \right]\). For the weights \(\overset{\lower0.5em\hbox{$\smash{\scriptscriptstyle\rightharpoonup}$}}{H}\), the contrast intensity is represented by the standard deviation \(\:{S}_{H}\), as shown in Eqs. (4)-(5):

The conflicting character is then represented by the correlation coefficients between \(\overset{\lower0.5em\hbox{$\smash{\scriptscriptstyle\rightharpoonup}$}}{H}\) and the other two weights.The correlation coefficient between \(\overset{\lower0.5em\hbox{$\smash{\scriptscriptstyle\rightharpoonup}$}}{H}\) and \(\overset{\lower0.5em\hbox{$\smash{\scriptscriptstyle\rightharpoonup}$}}{E}\) is labelled as rHE, and the correlation coefficient between \(\overset{\lower0.5em\hbox{$\smash{\scriptscriptstyle\rightharpoonup}$}}{H}\) and \(\overset{\lower0.5em\hbox{$\smash{\scriptscriptstyle\rightharpoonup}$}}{V}\) is labelled as rHV, then the conflicting character RH is calculated by Eq. (6).

Similarly, the above two metrics for weights \(\overset{\lower0.5em\hbox{$\smash{\scriptscriptstyle\rightharpoonup}$}}{E}\) and \(\overset{\lower0.5em\hbox{$\smash{\scriptscriptstyle\rightharpoonup}$}}{V}\) can be calculated. Finally, the combined weight \(\:\stackrel{⃑}{W}=\left[{W}_{a1},\:{W}_{a2},\:\dots\:,\:{W}_{a9}\right]\) can be calculated according to Eq. (7).

Evaluation of composite performance Q

After determining the combined weights of the indicators, the next step is to evaluate the composite performance of the slope. Since only the values of fourth-level indicators can be obtained directly, it is necessary to composite the indicators from lower to higher levels. In the proposed slope resilience assessment framework, the composite of indicators at all levels is the normalisation of weighted indicators. Taking the third-level indicators \(\:{a}_{1}\) to \(\:{a}_{9}\) as an example, the weighted value \(\:N\left(i\right)\) of these indicators at the ith moment can be calculated according to Eq. (8). Then the second-level indicator \(\:A\left(i\right)\) at that moment is the normalised \(\:N\left(i\right)\) over the whole resilience assessment time history, as shown in Eq. (9).

This composite process is applied to each level of the slope performance indicator system, and finally the first-level indicator composited from the three second-level indicators is the composite slope performance \(\:Q\left(i\right)\) at the ith moment. The composite performance at each moment constitutes the slope performance curve \(\:Q\left(t\right)\) in Fig. 2.

With the slope performance curve, the slope resilience metric \(\:{Re}_{s}\) can be calculated according to the resilience evaluation model developed in Sect. 2, as Eq. (1). In this study, the slope resilience metrics are classified using the equidistant interval division method:\(\:\:0.75<{Re}_{s}<1.0\) for high resilience slopes; \(\:0.5<{Re}_{s}<0.75\) for moderate resilience slopes; and \(\:{Re}_{s}<0.5\) for low resilience slopes.

Case: excavation and reinforcement of a high cut slope under the effect of rainfall

Project overview

In the present study, a high cut slope studied by Li et al. was selected as a case31. Our proposed slope resilience assessment framework was applied to analyse the resilience of this slope during continuous excavation and rainfall impacts. The slope is located on the west side of the Renbo Expressway in Guangdong Province, China. According to the geological investigation, the soil and rock layers of the analysed slope are dominated by residual silty clay and weathered siltstone, with many joints and poor mechanical properties. In order to meet the needs of the expressway, the slope was designed for six excavations. The 1st excavation is reinforced with four rows of anchor lattice beams. The 2rd ~ 4th excavation is reinforced with three rows of anchor cable frame beams, and the designed prestress of the anchor cables is 400 kN. The design diagram of the slope section is shown in Fig. 5.

The construction of this slope began in October 2016. Initially, the upper three parts of the slope were excavated continuously, during which no reinforcement measures were taken, resulting in a shallow collapse. Subsequently, the three excavations were reinforced and the fourth part was excavated. However, continuous rainfall in March 2017 gradually reduced the stability of the slope. The rainfall eventually led to cracks appearing near the electrical tower on the top of the slope. Subsequently, to prevent the overall slope failure, the excavated part of the fourth part was reinforced with anchor cables. After the anchor cable was tensioned, backfilling was adopted for reinforcement, which restored the stability of the slope.

Application of the slope resilience assessment framework

Performance indicator system

The selection of indicators of performance indicator system was based on the monitoring scheme and the project information of the slope case in the literature31. Based on the support structure and monitoring items of the slope case, a performance indicator system containing 72 fourth-level indicators was established. Since there is no building at the top of slope, the second-level indicators are only A and B. For third-level indicators, there are 10 indicators in total, including \(\:{a}_{1}\) to \(\:{a}_{8}\), as well as \(\:{b}_{3}\) and \(\:{b}_{4}\) in Fig. 4, while the fourth-level indicators are the multiple monitoring locations corresponding to each third-level indicator. The values of the fourth-level indicators are all field monitoring data obtained from the published literature and proved by field photos, so the reliability of monitoring data is guaranteed. The performance indicator system for this slope case is shown in Fig. 6.

Composite performance of slope

Next, the performance curve of the case slope during continuous excavation, rainfall, multiple reinforcement and recovery is determined. The prerequisite for calculating the slope’s composite performance Q is to determine the combined weights of indicators at each level. The analytic hierarchy process is used to determine the subjective weights, and then the entropy weight method and the coefficient of variation method are used to determine the two objective weights. The process of obtaining various weights is described in Sect. 3.3. Finally, the combined weights of each indicator are calculated according to Eq. (7) and are summarised in Table 3.

Once the combined weights are determined, the slope composite performance \(\:Q\left(i\right)\) corresponding to each moment is calculated according to the steps in Sect. 3.4. The composite performance at each moment constitutes the performance curve of the case slope.

Results and discussion of the resilience assessment

The slope performance curve obtained from the resilience assessment framework is shown in Fig. 7, which is divided into nine stages based on the case history (including excavation, disaster, and reinforcement). The type of each stage is marked by colour, disturbed stage in red, evolution stage in blue, and recovery stage in green. The case histories are also labelled in the figure, and the various damage phenomena in the red boxes are demonstrated by field investigations. For case histories and damage photos, please refer to the study by Li et al.31.

As can be seen in Fig. 7, the slope performance decreases with continuous excavation. This is due to the fact that excavation of a stable natural slope leads to slope unloading, which ultimately results in a shallow collapse. After this disturbance of continuous excavation, there is still a small decrease of slope performance in the evolutionary stage 2 in Fig. 7, which indicates that the slope has not returned to stability yet. Subsequently, the upper three excavations were reinforced, and a fourth part of slope was also excavated in this period. The slope performance continued to improve during this period, as the stage 3 in Fig. 7 shows. This indicates that this reinforcement was effective. In contrast, due to the small excavation height, the fourth excavation has little effect on the slope performance and is covered by the reinforcement. Therefore the slope performance curve of this period is a recovery stage. After the anchor cables are tensioned, the relative displacement between the components leads to a loss of pre-stress. This is shown in the performance curve as a decrease in the evolution stage after reinforcement, such as stage 4 in Fig. 7. Subsequently, the slope damage developed rapidly during the rainfall with a local uplift on the slope leading edge. After the rainfall ended, cracks appeared at the slope top, which is a sign of approaching slope failure. During the corresponding period in Fig. 7, the slope performance rapidly decreased from 87.14 to 20.43%, accurately reflecting the slope damage caused by rainfall. The fourth layer of excavation was immediately reinforced to prevent overall failure of the slope, but the monitoring data indicated that this was not sufficient to prevent slope failure. The slope performance gradually remained stable until the backfill was completed. This recovery process is also reflected in the performance curve, shown as stages 6 to 9 in Fig. 7. In addition, the slope profiles at different periods are shown in Fig. 8, which can be helpful to visually understand the whole case history.

The above comparison of the case slope histories and the performance curve shows that the composite performance obtained from the proposed resilience assessment framework is consistent with the safety status of slope. Therefore, the slope resilience assessment framework proposed in this paper is able to reflect the slope performance variations during disturbance and recovery processes. Finally, the performance curve is analysed using the developed slope resilience evaluation model. The resilience metric \(\:{Re}_{s}\) of the case slope during continuous excavation, rainfall and multiple reinforcement can be calculated to be 0.65 by Eq. (1). According to the classification of resilience metrics above, the slope in this case is a moderately resilience slope. The analysis results of slopes in previous disasters using the proposed framework can help decision makers to choose the optimal recovery solution. Based on the performance curve, the manager of this slope can directly conduct soil backfilling when facing similar situations in the future to save the repair time and repair cost.

In addition to comparing with case slope histories, it is also necessary to compare the results of the resilience evaluation model proposed in this study with existing model. The resilience evaluation model applicable to tunnel linings proposed by Lin et al. is used as an example for comparison20. The model proposed by Lin et al. used diameter convergence as a single performance indicator to obtain the performance curve. As mentioned in Sect. 2.2, the model cannot be directly applied to slopes. Therefore, some modifications were made to this model. Since there is no diameter convergence for slopes, the diameter convergence was modified to slope horizontal displacements with similar meanings. Since it is difficult to obtain the performance at the beginning of the life cycle for the slope, it was modified to the initial performance at the beginning of the disaster.

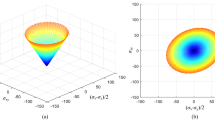

The modified existing model was subsequently applied to the resilience evaluation of the case slope. This model only considered a single performance indicator and could not simultaneously consider data from multiple monitoring points. Therefore, performance curves were calculated based on the displacement data from four monitoring points in the case slope separately, as shown in Fig. 9.

It can be seen from Fig. 9 that the performance curves obtained by the existing model are incomplete. This is because the monitoring of slope surface displacements was stopped at the later stage of the case and the borehole method was used to monitor internal slope displacements. Therefore, the performance curves obtained by the existing model considering a single performance indicator can only reflect the slope performance before 2017/4/11. In addition, the performance curves obtained by the existing model with data from different monitoring points all show a monotonically decreasing trend and do not reflect the performance recovery result from reinforcement. In contrast to the proposed resilience evaluation model, the existing model does not reflect the slope performance variations during disturbance and recovery processes.

Given the range of performance curves obtained by the existing model, the resilience metrics of the case slope were calculated for the period from 2016/9/27 to 2017/4/11, as shown in Fig. 10. It can be seen from the figure that the error between the resilience metrics calculated by the existing model and those calculated by the proposed model can be up to 23.40%.

Conclusions

This study presents a novel resilience evaluation model applicable to slopes, developed to address the characteristics of slope engineering. The model forms the basis of a slope resilience assessment framework, which was subsequently applied to assess the resilience of a slope case during continuous excavation and rainfall impacts. The main conclusions are as follows:

(1) The performance curve in the slope resilience evaluation model developed in this study reflects the characteristics that performance may also change after reinforcement is completed and that undergo multiple disturbance-recovery cycles during the service process.

(2) The multi-indicator performance indicator system developed in this study can comprehensively reflect the performance of the slope body, the supporting structure, and the nearby buildings. Compared with the resilience assessment model with multiple performance indicators, the performance curves obtained by the single-indicator model are inconsistent with the case slope history. And the error between the resilience metrics calculated by the single-indicator model and those calculated by the proposed model can be up to 23.40%.

(3) In the slope resilience assessment framework, the combined weights combining subjective and objective weights are obtained based on the CRITIC theory. This makes it possible to fully consider the advantages of different weights in the weighting of performance indicators.

(4) The resilience assessment framework was applied to a case of a slope affected by continuous excavation and rainfall. The results demonstrate that the proposed resilience assessment framework is able to reflect the slope performance variations during disturbance and recovery processes.

(5) The resilience assessment framework proposed in this study is most effective when used for slopes where damage progressively develops under disturbance, such as slopes under the influence of continuous rainfall.

It should be noted that this study still has some limitations. For example, resilience is a property that was recently introduced to the engineering field, and there are fewer cases where resilience assessment has been applied. This limits the availability of monitoring data, and hence the development of investigations on slope resilience.

For slope resilience, the potential area for future research is the quantitative description of the effects of some components on slope performance during the disturbance period. Taking the field of slope seismic resistance as an example, there have been many kinds of damping anchors that effectively reduce the damage of slopes under seismic effects. However, their effectiveness can only be described qualitatively and is difficult to describe quantitatively. While the slope resilience metric can quantitatively describe the variation of slope performance during the disturbance period.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Dou, H. Q., Huang, S. Y., Wang, H. & Jian, W. B. Repeated failure of a high cutting slope induced by excavation and rainfall: a case study in Fujian. Southeast. China B Eng. Geol. Environ. 81, 227 (2022).

Ganesh, R. & Sahoo, J. P. Coupled bearing capacity factor for Strip foundations on cohesive-frictional soil slopes under static and seismic conditions. Int. J. Geomech. 20 (11), 04020202 (2020).

Jin, L. L. et al. An analytical solution to predict slip-buckling failure of bedding rock slopes under the influence of top loading and earthquakes: case studies of Hejia landslide and Tangjiashan landslide. Landslides 21 (7), 1617–1627 (2024).

He, Y., Liu, Y., Hazarika, H. & Yuan, R. Stability analysis of seismic slopes with tensile strength cut-off. Comput. Geotech. 112, 245–256 (2019).

Ju, S. Y., Jia, J. Q. & Pan, X. G. Prediction framework of slope topographic amplification on seismic acceleration based on machine learning algorithms. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intel. 133, 108143 (2024).

Wang, L. M. et al. Amplification of thickness and topography of loess deposit on seismic ground motion and its seismic design methods. Soil. Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 126, 105090 (2019).

Ye, X. et al. Thermo-Hydro-poro-mechanical responses of a reservoir-induced landslide tracked by high-resolution fiber optic sensing nerves. J. Rock. Mech. Geotech. 16 (3), 1018–1032 (2024).

Segoni, S., Piciullo, L. & Gariano, S. L. A review of the recent literature on rainfall thresholds for landslide occurrence. Landslides 15 (8), 1483–1501 (2018).

Liu, S. Y., Shao, L. T. & Li, H. J. Slope stability analysis using the limit equilibrium method and two finite element methods. Comput. Geotech. 63, 291–298 (2015).

Zhang, T., Zheng, H. & Sun, C. Global method for stability analysis of anchored slopes. Int. J. Numer. Anal. Met. 43, 124–137 (2019).

Babu, G. L. S. & Mukesh, M. D. Effect of soil variability on reliability of soil slopes. Géotechnique 54 (5), 335–337 (2004).

Bai, T., Hu, X. D. & Gu, F. Practice of searching a noncircular critical slip surface in a slope with soil variability. Int. J. Geomech. 19 (3), 04018199 (2019).

Bui, H. H., Fukagawa, R., Sako, K. & Wells, J. C. Slope stability analysis and discontinuous slope failure simulation by elasto-plastic smoothed particle hydrodynamics (SPH). Géotechnique 61 (7), 565–574 (2011).

Sun, G. H., Lin, S., Zheng, H., Tan, Y. Z. & Sui, T. The virtual element method strength reduction technique for the stability analysis of stony soil slopes. Comput. Geotech. 119, 103349 (2020).

Jia, J. Q. & Ju, S. Y. Clustering-based method for locating critical slip surface using the strength reduction method. Comput. Geotech. 155, 105241 (2023).

Bruneau, M. et al. A framework to quantitatively assess and enhance the seismic resilience of communities. Earthq. Spectra. 19 (4), 733–752 (2003).

Tierney, K. & Bruneau, M. Conceptualized and measuring resilience: a key to disaster loss reduction. TR. News. 250, 14–17 (2007).

Attoh-okine, N. O., Cooper, A. T. & Mensah, S. A. Formulation of Resilience Index of Urban infrastructure using belief functions. IEEE Syst. J. 3 (2), 147–153 (2009).

Huang, H. W. & Zhang, D. M. Resilience analysis of shield tunnel lining under extreme surcharge: characterization and field application. Tunn. Undergr. Sp Tech. 51, 301–312 (2016).

Lin, X. T., Chen, X. S., Su, D., Han, K. H. & Zhu, M. An analytical model to evaluate the resilience of shield tunnel linings considering multistage disturbances and recoveries. Tunn. Undergr. Sp Tech. 127, 104581 (2022).

Chen, R. P., Lang, Z. X., Zhang, C., Zhao, N. N. & Deng P. A paradigm for seismic resilience assessment of subway system. Tunn. Undergr. Sp Tech. 135, 105061 (2023).

Han, K. H. et al. A resilience assessment framework for existing underground structures under adjacent construction disturbance. Tunn. Undergr. Sp Tech. 141, 105339 (2023).

Qiu, T. et al. An adaptation resilience assessment framework for key components of prefabricated underground stations. Tunn. Undergr. Sp Tech. 136, 105037 (2023).

Das, J. T., Puppala, A. J., Bheemasetti, T. V., Walshire, L. A. & Corcoran, M. K. Sustainability and resilience analyses in slope stabilisation. P. I. Civil. Eng. -Eng Su. 171, 25–36 (2018).

He, Z. Y., Huang, Y. & Zhao, C. Z. A preliminary general framework for seismic resilience assessment of slope engineering. B Eng. Geol. Environ. 81 (11), 463 (2022).

Ayyub, B. M. Systems Resilience for Multihazard environments: Definition, Metrics, and valuation for decision making. Risk Anal. 34 (2), 340–355 (2014).

British Standards Institution. Eurocode 7: Geotechnical design. Part 1: General rules. BS EN1997-1. (2004).

National Standardization Administration of China. Technical code for building slope engineering. GB50330-2013. (2013).

National Standardization Administration of China. Technical code for appraisal and reinforcement of building slope. GB50843-2013. (2013).

Diakoulaki, D., Mavrotas, G. & Papayannakis, L. Determining objective weights in multiple criteria problems – the CRITIC method. Comput. Oper. Res. 22 (7), 763–770 (1995).

Li, Q., Wang, Y. M., Zhang, K. B., Yu, H. & Tao, Z. Y. Field investigation and numerical study of a siltstone slope instability induced by excavation and rainfall. Landslides 17 (6), 1485–1499 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 52278332), the Research Project of China Three Gorges Corporation (Grant No.1524020067) and the Science and technology plan of Fujian Province under Grant No.2022I0014.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Shiyuan Ju designed the framework and wrote the main manuscript text; Jinqing Jia conceptualised the study; Yong Zhao and Xin Xiang analysed the data; and Bingxiong Tu substantively revised the work. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ju, S., Jia, J., Zhao, Y. et al. A resilience assessment framework for slopes considering multiple performance indicators. Sci Rep 15, 3019 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87599-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87599-z