Abstract

This study aimed to identify clinical characteristics and develop a prognostic model for non-neutropenic patients with invasive pulmonary aspergillosis (IPA). A retrospective analysis of 151 IPA patients was conducted, with patients categorized into survival (n = 117) and death (n = 34) groups. Clinical data, including demographics, laboratory tests, and imaging, were collected. Multivariate Cox regression analysis identified glucocorticoid use (odds ratio [OR] = 30.223, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 2.676–341.306), intensive care unit admission (OR = 0.133, 95% CI: 0.023–0.758), and the arterial oxygen partial pressure/fractional inspired oxygen ratio (OR = 0.994, 95% CI: 0.990–0.999) as significant predictors of 28-day mortality. A prognostic model was developed based on these factors, showing high predictive accuracy (receiver operating characteristic curve area of 0.918). The model’s clinical applicability was validated through calibration curves, bootstrap internal validation, decision curve analysis, and clinical impact curves. Kaplan–Meier analysis further confirmed its utility, indicating a worse prognosis for high-risk patients within 50 days and the highest survival rate at 14 days. This novel model offers valuable insights for predicting survival in non-neutropenic IPA patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis (IPA) is a severe opportunistic infection that mainly occurs among immunosuppressed or hospitalized patients with severe underlying diseases1,2. The burden of IPA has been reported to be increasing, along with high rates of morbidity and mortality3,4. Over the past few decades, the population susceptible to IPA has expanded, and IPA has been recognized as an emerging disease in non-neutropenic patients, with an incidence in this group varying between 0.33% and 5.8% 5. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and corticosteroid therapy have been frequently observed and may be considered as key risk factors in this cohort6. IPA is more commonly recognized as a complication of severe influenza infection and COVID-19 infection7,8.

IPA in non-neutropenic patients is associated with a poor prognosis, with mortality rates exceeding 50%, mainly due to a delayed diagnosis or underlying diseases9,10. In such patients, diagnosing IPA can be challenging due to nonspecific signs and symptoms, the difficulty in distinguishing colonization from infection, and the lower sensitivity of microbiological and radiological tests compared to those of immunocompromised patients6,11. These challenges result in low clinical suspicion and a delayed diagnosis, leading to late therapeutic intervention. Since the clinical characteristics and mortality risk factors of IPA in non-neutropenic patients are not well known, we performed a retrospective study reviewing non-neutropenic patients with IPA admitted to a teaching hospital. A better understanding of IPA in non-neutropenic patients may help to improve outcomes for this potentially treatable disease.

The aim of this study was to provide clinicians with a summary of the characteristics and mortality risk factors of IPA in non-neutropenic patients. Additionally, we aimed to develop a prognostic model to enhance the management of non-neutropenic patients with IPA.

Results

Baseline characteristics

A total of 151 non-neutropenic patients with IPA were included in this study. The detailed clinical characteristics are provided in Table 1 and Supplementary Table 1. The patient population was predominantly elderly, with an average age of 69 years, and nearly 60% were male. Approximately 40% had a history of smoking, and a significant proportion (39.7%) required admission to the intensive care unit (ICU). Common symptoms included shortness of breath (88.7%), cough (86.8%), chest tightness (74.2%), and fever (56.9%). Chest imaging frequently revealed lung consolidation (71.5%), pleural thickening (76.2%), and patchy shadows (66.2%), with both lungs affected in 50.1% of cases. Most patients received antibiotic (94.7%) and voriconazole (95.4%) treatments, and 72.2% were treated with glucocorticoids. Laboratory tests revealed a significantly elevated white blood cell count (reference range: 3.5–9.5 × 10⁹; observed: 63/151), along with increased levels of procalcitonin (reference: ≤0.094 ng/mL; observed: 97/151), interleukin-6 (reference: ≤7 pg/mL; observed: 97/151), and C-reactive protein (reference: <10 mg/L; observed: 121/151), indicating substantial inflammation.Significant differences in white blood cell levels, neutrophil counts, and C-reactive protein levels were found between deceased and surviving patients (P < 0.05), with higher levels in the deceased group. No significant differences were observed for other laboratory parameters (P > 0.05). Underlying conditions were prevalent, with respiratory disease (60.3%), diabetes (59.6%), and hypertension (45.7%) being the most common. Severity scores, including an average Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score of 10.49 and an Acute Physiologic Assessment and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II score of 13.92, indicated high levels of organ dysfunction and illness severity.

Of the 151 patients, Aspergillus flavus infection was found in 36 cases, Aspergillus fumigatus in 72 cases, Aspergillus terreus in 29 cases, and Aspergillus niger in 14 cases (Supplementary Table 1). Significant differences were noted in the Confusion, Uremia, Respiratory Rate, Blood Pressure, Age ≥ 65 years (CURB-65) score, APACHE II score, respiratory distress, bilateral lung involvement, and diabetes among the infection types (Supplementary Table 1). Specifically, A. flavus infections had higher CURB-65 (P = 0.021) and APACHE II scores (P = 0.013), along with higher rates of respiratory distress (P = 0.017), bilateral lung involvement (P = 0.000), and diabetes (P = 0.018) compared to the other types of infection.

Univariate analysis

As shown in Table 1, the death group had a lower arterial oxygen partial pressure/fractional inspired oxygen (PaO2/FiO2) ratio (187.18 ± 94.97 vs. 264.15 ± 97.47) compared to the survival group. Conversely, the death group had a higher CURB-65 score (3.44 ± 0.79 vs. 1.53 ± 1.11), SOFA score (14.35 ± 1.32 vs. 9.38 ± 2.05), fungus score (42.24 ± 2.45 vs. 31.10 ± 5.96), APACHE II score (20.71 ± 4.24 vs. 11.95 ± 3.71), white blood cell count (12.25 ± 6.69 vs. 9.48 ± 5.53 × 109/L), neutrophil count (10.51 ± 6.30 vs. 7.72 ± 4.86 × 109/L), and C-reactive protein level (60.19 ± 66.97 vs. 38.09 ± 50.26) compared to the survival group.

Additionally, the frequencies of organ failure (16.2% vs. 64.7%), ICU admission (26.5%) vs. 85.3%), respiratory distress (44.4% vs. 82.4%), pleural effusion (47.9% vs. 67.6%), patchy shadows (61.5% vs. 82.4%), lung consolidation (67.5% vs. 85.3%), bilateral lung involvement (40.2% vs. 88.2%), pleural thickening (71.8% vs. 91.2%), diabetes (53.8% vs. 79.4%), coronary heart disease (23.9% vs. 44.1%), and other illnesses (18.8% vs. 47.1%) were lower in the survival group than in the death group, with statistical significance (P < 0.05).

Multivariate analysis and nomogram model

Multivariate backward COX regression revealed that glucocorticoid use [odds ratio (OR) = 30.223, 95% confidence interval (CI): 2.676–341.306], ICU admission (OR = 0.133, 95% CI: 0.023–0.758), and PaO2/FiO2 ratio (OR = 0.994, 95% CI: 0.990–0.999) were associated with the 28-day mortality (Table 2). Next, a model was constructed, assessed for the 14- or 28-day mortality, and visualized by the nomogram (Fig. 1). The total score was calculated by summing the scores of each risk factor, with higher total scores indicating a greater probability of mortality.

Model performance, assessment, and validation

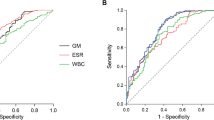

Compared to the area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve (AUC) of glucocorticoid use (AUC: 0.789, 95% CI: 0.736–0.842), ICU admission (AUC: 0.794, 95% CI: 0.721–0.867), and PaO2/FiO2 ratio (AUC: 0.737, 95% CI: 0.640–0.833), the model demonstrated the highest AUC (AUC: 0.918, 95% CI: 0.870–0.965) for the 28-day mortality. The model achieved a sensitivity of 0.855 and a specificity of 0.912 (Table 3; Fig. 2). Additionally, the model exhibited a higher AUC for the 14-day mortality compared to the 28-day mortality (Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2).

As shown in Fig. 3A, the calibration curves closely fluctuated around the ideal curve, indicating a high model accuracy. Furthermore, the Brier score was less than 0.25, suggesting a good performance overall. Internal validation of the model was conducted using 100 bootstrap resampling, yielding a C-index value of 0.918, thus demonstrating an excellent discriminatory ability (Fig. 3B). The decision curve analysis indicated that the model has good clinical utility (Fig. 3C).

Calibration curves and receiver operating curve analysis of the prognostic model. The calibration curves (A) include an ideal diagonal reference line. The closer the other two lines are to this ideal line, the higher the accuracy of the model. The Brier score for the model was less than 0.25, indicating overall good performance. Internal validation of the model was performed using 100 bootstrap resampling, resulting in a C-index value of 0.918 (B), thus demonstrating an excellent discriminatory ability. The decision curve analysis (C) shows that the model has good clinical practicality.

The clinical impact curve was used to predict the risk stratification of patients with IPA, with a blue dashed line representing the number of actual risk events occurring at various threshold levels. The model demonstrated a better performance when the lines were closer within the range of 0.2 to 0.8 (Fig. 4).

Clinical impact curve. The clinical impact curve illustrates the model’s performance in identifying high-risk patients. The red solid line represents the number of high-risk patients per 1000 at each risk threshold, while the blue dashed line indicates the true positives. The horizontal axes show the correspondence between the high-risk threshold and the cost-benefit ratio.

According to the Kaplan–Meier analysis, the patients in the high-risk group experienced a worse prognosis within 50 days compared to the low-risk group, with a significant difference in the survival status between the two groups (P < 0.05; Fig. 5).

Discussion

Previously, IPA was primarily associated with severe immunodeficiency, but its incidence is increasing among non-immunocompromised individuals12,13. In these patients, atypical clinical manifestations often result in missed or delayed diagnoses, contributing to higher mortality rates14 and underscoring the need for a better understanding of this population. In this study, we retrospectively analyzed the clinical characteristics and prognoses of non-neutropenic patients with IPA. Significant differences were observed among infection types, with A. flavus showing higher CURB-65 and APACHE II scores as well as increased rates of respiratory distress, bilateral lung involvement, and diabetes. Univariate analysis identified various mortality risk factors, including respiratory distress, PaO2/FiO2 ratio, severity scores, lab markers, underlying conditions, and radiological findings. In addition, multivariate analysis revealed an association between the 28-day mortality and glucocorticoid use, ICU admission, and the PaO2/FiO2 ratio. A novel prognostic model incorporating these factors was developed, demonstrating a strong predictive capability (AUC = 0.918). This model may aid in the early identification of high-risk patients and guide therapeutic interventions to improve outcomes.

Although A. flavus is less common, it presents more severely, with higher CURB-65 and APACHE II scores, increased respiratory distress, and more extensive lesions. Our study found A. fumigatus to be the most prevalent species, accounting for 47.7% of reported cases. This finding aligns with a Chinese systematic review that reported A. fumigatus as the most prevalent species in China, at 75.14% 15. Similarly, a Spanish cohort also identified A. fumigatus as the most common species, representing 51.94% of cases16. Moreover, the A. flavus strain demonstrated a higher virulence than A. fumigatus and A. niger in the Galleria mellonella larvae model17. Larvae infected with A. flavus also had a lower survival rate compared to those infected with A. niger or A. fumigatus (P < 0.05)18. A. flavus, known for producing aflatoxins19, caused more severe infection, with a lower survival rate and a greater fungal presence in the subcuticular areas of infected larvae. Additionally, larvae infected with A. flavus showed a stronger host response, as evidenced by increased melanization, which supports our findings.

The PaO2/FiO2 ratio is a well-established marker for assessing the severity of acute respiratory distress syndrome and other pulmonary complications20,21. In our study, this ratio was closely associated with the 28-day mortality in IPA patients, underscoring its critical role in the management of prognosis22. Additionally, the integration of the PaO2/FiO2 ratio into our prognostic model highlights the importance of pulmonary function in managing IPA. This finding aligns with previous studies that have shown greater risks of early respiratory failure and mortality in patients with compromised pulmonary function23. Therefore, close monitoring and early intervention for impaired pulmonary function, particularly in non-neutropenic IPA patients with lower PaO2/FiO2 ratios, are crucial for improving patient outcomes. The significant association between a lower PaO2/FiO2 ratio and a higher mortality is also consistent with findings from other studies on respiratory infections and complications24,25.

Although univariate analysis did not show a statistically significant difference in glucocorticoid use between the survival and death groups, multivariate analysis indicated an association between glucocorticoid use and an increased mortality. Therefore, this factor was incorporated into the prognostic model, aiding in the management of non-neutropenic IPA patients. Glucocorticoids are widely used in clinical practice, particularly for treating inflammatory and autoimmune conditions. However, their immunosuppressive effects can predispose patients to opportunistic infections like IPA26. In our study, glucocorticoid use was more prevalent in the death group, highlighting the delicate balance between the therapeutic benefits and risks of glucocorticoid therapy27,28. The higher mortality observed underscores the need for cautious use of glucocorticoids in patients at risk of IPA, especially those with additional conditions that may further compromise their immune response29. Clinicians should carefully weigh the risks and benefits of glucocorticoid therapy and consider alternative treatments when possible.

ICU admission emerged as another critical factor associated with a higher mortality in non-neutropenic IPA patients. ICU admission typically indicates more severe illness and the need for intensive monitoring and interventions30,31. Our study found that ICU admission was independently associated with a higher risk of mortality, emphasizing the severe presentation in these patients. This finding suggests that non-neutropenic IPA patients admitted to the ICU require more aggressive management strategies, such as enhanced respiratory support and close monitoring of organ function, to improve outcomes.

The high AUC of the prognostic model, along with its sensitivity and specificity, indicates its strong potential as a clinical tool for predicting mortality in non-neutropenic IPA patients. The model’s performance was further validated through calibration curves, decision curve analysis, and clinical impact curves, which confirmed its accuracy and clinical utility. If validated, this model could be used to stratify patients based on their risk of mortality, allowing for targeted interventions and resource allocation in a clinical setting. For instance, patients identified as high-risk could receive early and aggressive antifungal therapy, closer monitoring, and possibly admission to a higher level of care, such as the ICU, to improve their chances of survival.

However, this study had several limitations. First, in the absence of specific host factors and characteristic radiological findings, culturing Aspergillus alone is insufficient to confirm IPA, as it is frequently a contaminant. The retrospective design may have introduced selection bias, as patient inclusion depended on the availability of complete clinical data, which could affect the generalizability of the findings. Second, this study was conducted at a single center, limiting its applicability to other settings. Third, only non-neutropenic patients without an immunocompromised status were included, so the findings may not be applicable to neutropenic or severely immunocompromised patients. Finally, prospective multicenter studies are needed to validate the prognostic model across diverse clinical environments and to confirm its utility in different patient populations.

Conclusions

In summary, this study identified key clinical characteristics associated with mortality in non-neutropenic IPA patients and developed a robust prognostic model incorporating glucocorticoid use, ICU admission, and the PaO2/FiO2 ratio. This model demonstrated a strong predictive capability and could serve as a valuable tool for clinicians to identify high-risk patients and to optimize their management. The typical chest computed tomography manifestations of IPA, such as the halo sign and crescent sign, are more frequently observed in patients with hematological diseases or hematologic malignancies undergoing chemotherapy, and they are less common in non-neutropenic patients32. Therefore, lung consolidation and pleural effusion were frequently observed in this study, which is consistent with the findings previously reported14,33. This emphasized that IPA imaging patterns in non-neutropenic patients differ significantly from the conventional fungal pneumonia patterns observed in neutropenic patients. Given the small sample size of this study, drawing definitive conclusions on imaging patterns is challenging. Despite its limitations, this study provided important insights into the factors influencing the prognosis of non-neutropenic IPA patients, paving the way for future research and the potential for improved patient outcomes. However, further studies are required to validate this model in broader clinical settings and to explore its application in different patient populations.

Methods

Ethics

This study adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki and was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the General Hospital of Ningxia Medical University (Approval No. KYLL-2024-0954). All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. The written informed consent to participate was obtained from all the patients.

Subjects

Between September 2020 and March 2024, a retrospective analysis was conducted on non-neutropenic patients diagnosed with IPA. All patients in this study received medical care at the General Hospital of Ningxia Medical University. According to the 28-day mortality, patients were classified into either the survival or death group.

This study included patients who were ≥ 18 years and met the diagnostic criteria for IPA34. Briefly, proven IPA was defined by demonstrating tissue invasion by Aspergillus spp. through histological or cytopathological examination of a specimen obtained from a normally sterile site, such as lung tissue via biopsy or needle aspiration, showing the presence of hyphae consistent with Aspergillus. Additionally, a proven diagnosis also could have been made by isolating Aspergillus spp. from culture of such a specimen, provided it originated from a lesion consistent with infection and was obtained from a normally sterile site. Probable IPA was characterized by the presence of compatible clinical symptoms, with at least one of the following: persistent fever despite at least three days of appropriate antibiotic therapy, relapse of fever, pleuritic chest pain, dyspnea, hemoptysis, or worsening respiratory insufficiency. These clinical signs must have been accompanied by ICU-specific host factors that predispose one to aspergillosis, including influenza, COVID-19, moderate-to-severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), decompensated liver cirrhosis, uncontrolled human immunodeficiency virus infection (CD4 count < 200/mm³), or presence of solid tumors. Additionally, radiological findings of pulmonary infiltrates or cavitary lesions, combined with mycological evidence such as a positive Aspergillus culture from bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF), or detection of galactomannan in serum (ODI > 0.5) or BALF (ODI ≥ 1.0), were required for a probable diagnosis.

The exclusion criteria were as follows: patients with incomplete clinical data records, those hospitalized for less than 24 h, patients with neutropenia (neutrophil count < 0.5 × 109/L) or severe immunosuppression due to human immunodeficiency virus infection, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, or solid organ transplantation, and individuals with mental disorders or congenital developmental deficiencies.

Data collection

The clinicopathological characteristics were collected upon admission, including age, sex, symptoms, vital signs, underlying diseases (such as diabetes, respiratory diseases, cardiovascular diseases, kidney diseases, etc.), laboratory examinations (routine blood tests, C-reactive protein, procalcitonin, (1–3)-β-D-glucan assay, galactomannan assay, microbiological assays, etc.), chest computed tomography imaging, and blood gas examination (such as the PaO2/FiO2 ratio).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS (version 23.0) and R language (version 4.3.2). Categorical variables were described as counts and percentages, with differences between groups compared using the chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test. Quantitative variables were expressed as the mean and standard deviation, and they were compared using the t test or Mann–Whitney U test.

Univariate and multivariate (backward stepwise) Cox regression analyses were employed to assess the prognostic value of various clinicopathological factors. A predictive model was then constructed based on selected variables. The predictive accuracy of this model was evaluated through ROC curves and calibration curves. Additionally, decision curve analysis and clinical impact curves were used to assess the clinical benefits of the model.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to limitations of ethical approval involving the patient data and anonymity but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Change history

20 March 2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93430-6

Abbreviations

- APACHE:

-

Acute physiologic assessment and chronic health evaluation

- BALF:

-

Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- ICU:

-

Intensive care unit

- IPA:

-

Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- PaO2/FiO2 :

-

Arterial oxygen partial pressure/fractional inspired oxygen

- ROC:

-

Receiver operating characteristic

- SOFA:

-

Sequential organ failure assessment

References

Naaraayan, A., Kavian, R., Lederman, J., Basak, P. & Jesmajian, S. Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis - case report and review of literature. J. Community Hosp. Intern. Med. Perspect. 5 (1), 26322. https://doi.org/10.3402/jchimp.v5.26322 (2015).

Lee, W. C. et al. Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis among patients with severe community-acquired pneumonia and influenza in ICUs: a retrospective cohort study. Pneumonia (Nathan). 16 (1), 10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41479-024-00129-9 (2024).

Tavakoli, M. et al. National trends in incidence, prevalence and disability-adjusted life years of invasive aspergillosis in Iran: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Expert Rev. Respir Med. 13 (11), 1121–1134. https://doi.org/10.1080/17476348.2019.1657835 (2019).

Rubio, P. M. et al. Increasing incidence of invasive aspergillosis in pediatric hematology oncology patients over the last decade: a retrospective single centre study. J. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 31 (9), 642–646. https://doi.org/10.1097/MPH.0b013e3181acd956 (2009).

Bassetti, M., Peghin, M. & Vena, A. challenges and solution of invasive aspergillosis in non-neutropenic patients: a review. Infect. Dis. Ther. 7 (1), 17–27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40121-017-0183-9 (2018).

Bassetti, M. et al. How to manage aspergillosis in non-neutropenic intensive care unit patients. Crit. Care. 18 (4), 458. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-014-0458-4 (2014).

Song, L. et al. Investigation of risk factors for invasive pulmonary aspergillosis among patients with COVID-19. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 20364. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-71455-7 (2024).

Prattes, J. et al. Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis complicating COVID-19 in the ICU - a case report. Med. Mycol. Case Rep. 31, 2–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mmcr.2020.05.001 (2021).

Dai, Z., Zhao, H., Cai, S., Lv, Y. & Tong, W. Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in non-neutropenic patients with and without underlying disease: a single-centre retrospective analysis of 52 subjects. Respirology 18 (2), 323–331. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1843.2012.02283.x (2013).

Garbino, J. et al. Survey of aspergillosis in non-neutropenic patients in Swiss teaching hospitals. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 17 (9), 1366–1371. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-0691.2010.03402.x (2011).

Park, S. Y. et al. Computed tomography findings in invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in non-neutropenic transplant recipients and neutropenic patients, and their prognostic value. J. Infect. 63 (6), 447–456. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinf.2011.08.007 (2011).

Bulpa, P., Dive, A. & Sibille, Y. Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur. Respir J. 30 (4), 782–800. https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00062206 (2007).

Blot, S. I. et al. A clinical algorithm to diagnose invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in critically ill patients. Am. J. Respir Crit. Care Med. 186 (1), 56–64. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201111-1978OC (2012).

Cornillet, A. et al. Comparison of epidemiological, clinical, and biological features of invasive aspergillosis in neutropenic and nonneutropenic patients: a 6-year survey. Clin. Infect. Dis. 43 (5), 577–584. https://doi.org/10.1086/505870 (2006).

Khan, S. et al. Distribution of aspergillus species and risk factors for aspergillosis in mainland China: a systematic review. Ther. Adv. Infect. Dis. 11, 20499361241252537. https://doi.org/10.1177/20499361241252537 (2024).

Lucio, J. et al. Distribution of aspergillus species and prevalence of azole resistance in clinical and environmental samples from a Spanish hospital during a three-year study period. Mycoses 67 (4), e13719. https://doi.org/10.1111/myc.13719 (2024).

Mohamadnia, A. et al. Molecular identification, phylogenetic analysis and antifungal susceptibility patterns of Aspergillusnidulans complex and aspergillusterreus complex isolated from clinical specimens. J. Mycol. Med. 30 (3), 101004. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mycmed.2020.101004 (2020).

Chen, B. et al. Virulence capacity of different aspergillus species from invasive pulmonary aspergillosis. Front. Immunol. 14, 1155184. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2023.1155184 (2023).

Balajee, S. A., Gribskov, J. L., Hanley, E., Nickle, D. & Marr, K. A. Aspergillus lentulus sp. nov., a new sibling species of A. Fumigatus. Eukaryot. Cell. 4 (3), 625–632. https://doi.org/10.1128/ec.4.3.625-632.2005 (2005).

Villar, J. et al. PaO2/FIO2, and Plateau pressure score: a proposal for a simple outcome score in patients with the Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. Crit. Care Med. 44 (7), 1361–1369. https://doi.org/10.1097/ccm.0000000000001653 (2016). Age.

Bein, T. et al. The standard of care of patients with ARDS: ventilatory settings and rescue therapies for refractory hypoxemia. Intensive Care Med. 42 (5), 699–711. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-016-4325-4 (2016).

Upton, A., Kirby, K. A., Carpenter, P., Boeckh, M. & Marr, K. A. Invasive aspergillosis following hematopoietic cell transplantation: outcomes and prognostic factors associated with mortality. Clin. Infect. Dis. 44 (4), 531–540. https://doi.org/10.1086/510592 (2007).

Parimon, T., Madtes, D. K., Au, D. H., Clark, J. G. & Chien, J. W. Pretransplant lung function, respiratory failure, and mortality after stem cell transplantation. Am. J. Respir Crit. Care Med. 172 (3), 384–390. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.200502-212OC (2005).

Toh, H. S., Jiang, M. Y. & Tay, H. T. Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in severe complicated influenza A. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 112 (12), 810–811. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfma.2013.10.018 (2013).

Ferrer, M. et al. Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia and PaO(2)/F(I)O(2) diagnostic accuracy: changing the paradigm? J. Clin. Med. 8 (8), 1217. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm8081217 (2019).

Biyun, L., Yahui, H., Yuanfang, L., Xifeng, G. & Dao, W. Risk factors for invasive fungal infections after haematopoietic stem cell transplantation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 30 (5), 601–610. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmi.2024.01.005 (2024).

Cutolo, M. et al. To treat or not to treat rheumatoid arthritis with glucocorticoids? A reheated debate. Autoimmun. Rev. 23 (1), 103437. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autrev.2023.103437 (2024).

Kew, K. M. & Seniukovich, A. Inhaled steroids and risk of pneumonia for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. Cd010115 (2014). (2014). (3) https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD010115.pub2

Lewis, R. E. & Kontoyiannis, D. P. Invasive aspergillosis in glucocorticoid-treated patients. Med. Mycol. 47 (Suppl 1), S271–281. https://doi.org/10.1080/13693780802227159 (2009).

Huang, C., Lin, L. & Kuo, S. Risk factors for mortality in Stenotrophomonas maltophilia bacteremia - a meta-analysis. Infect. Dis. (Lond). 56 (5), 335–347. https://doi.org/10.1080/23744235.2024.2324365 (2024).

Cilloniz, C. et al. Risk factors associated with mortality among elderly patients with COVID-19: data from 55 intensive care units in Spain. Pulmonology 29 (5), 362–374. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pulmoe.2023.01.007 (2023).

Chen, F. et al. Dynamic monitor of CT scan within short interval in invasive pulmonary aspergillosis for nonneutropenic patients: a retrospective analysis in two centers. BMC Pulm Med. 21 (1), 142. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12890-021-01512-8 (2021).

Garg, A., Bhalla, A. S., Naranje, P., Vyas, S. & Garg, M. Decoding the guidelines of Invasive Pulmonary aspergillosis in critical care setting: imaging perspective. Indian J. Radiol. Imaging. 33 (3), 382–391. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0043-57004 (2023).

Bassetti, M. et al. Invasive fungal diseases in adult patients in intensive care unit (FUNDICU): 2024 consensus definitions from ESGCIP, EFISG, ESICM, ECMM, MSGERC, ISAC, and ISHAM. Intensive Care Med. 50 (4), 502–515. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-024-07341-7 (2024).

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82360022, to Jinyuan Zhu) and the Key Research and Development Project of Ningxia Province (No. 2022BEG03102, to Jinyuan Zhu).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

FL was responsible for the research design, data collection, and manuscript writing. WC was responsible for data collection and manuscript writing. HQ contributed to the research design and data collection. YHY and YY both participated in data collection and provided supportive contributions. ZW critically revised the manuscript content. JZ was involved in the research design and critically revised the manuscript content.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki and was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the General Hospital of Ningxia Medical University (Approval No. KYLL-2024-0954). All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. The written informed consent to participate was obtained from all the patients.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this Article was revised: In the original version of this Article, Jinyuan Zhu was omitted as a co-corresponding author. Correspondence and requests for materials should also be addressed to zhujy1208@126.com.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, F., Chen, W., Qi, H. et al. Clinical characteristics and prognosis of patients treated as invasive pulmonary aspergillosis outside of severe immunosuppression. Sci Rep 15, 3379 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87605-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87605-4