Abstract

The mutant waxy allele (wx1) is responsible for increased amylopectin in maize starch, with a wide range of food and industrial applications. The amino acid profile of waxy maize resembles normal maize, making it particularly deficient in lysine and tryptophan. Therefore, the present study explored the combined effects of genes governing carbohydrate and protein composition on nutritional profile and kernel physical properties by crossing Quality Protein Maize (QPM) (o2o2/wx1+wx1+) and waxy (o2+o2+/wx1wx1) parents. Selected homozygous genotypic classes from F2 populations showed that double mutants (o2o2/wx1wx1) had the highest amount of lysine (mean: 0.396%), tryptophan (mean: 0.099%), and amylopectin (mean: 98.56%) than respective single mutants (o2o2/wx1+wx1+: lysine: 0.338%, tryptophan: 0.083%, amylopectin: 74.66%; o2+o2+/wx1wx1: lysine: 0.223%, tryptophan: 0.040%, amylopectin: 95.21%). The wx1 was found to impart an enhanced effect on the lysine and tryptophan, while o2 complemented enhanced amylopectin content in the population in the o2+o2+ and wx1+wx1+ genotypic background, respectively, besides o2o2wx1wx1 genotypes. The pattern of kernel hardness observed based on average genotypic values was o2+o2+/wx1+wx1+ (401.28 N) < o2+o2+/wx1wx1 (330.99 N) < o2o2/wx1wx1 (304.28 N) < o2o2/wx1+wx1+ (210.96 N). Therefore, with the distinctive effects of wx1 and o2, improving lysine, tryptophan, and amylopectin while maintaining kernel hardness is feasible while breeding for o2o2/wx1wx1 germplasm and enhancing the utilization spectrum of waxy maize.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The myriad applications of maize have established it as a popular third leading cereal crop cultivated across diverse ecologies in more than 170 countries, while India’s contribution to the total area and global production of maize is ranked 4th and 6th, respectively1. Apart from being a model crop in genetic studies for decades, maize has achieved significant economic success due to its exclusive specialty traits. These traits enhance its value across end uses, primarily as feed and raw material in industrial applications and food2. Waxy maize, a specialty corn, forms a major part of the diet as a breakfast item and a vegetable in Southeast Asian countries, due to the sticky quality of grains3. Despite amylopectin being a primary component in all maize types, waxy maize is characterized by lesser amylose content (0 to 8%) and very high amylopectin, which therefore, imparts higher viscosity, and is commonly referred to as glutinous maize4. The wide industrial applications of waxy maize are attributable to highly crystalline starch structures characterized by tandem linked clusters and low retrogradation tendencies5. The normal maize starch, however, containing 25–28% amylose with the least viscosity has specific applications in drug delivery, dietary fiber, and emulsion stability6,7,8. In the food sector, waxy maize starch is preferred as thickeners, fillers, and food additives, while in the paper industry, it is used as a sizing agent9, besides being used as an oil recovery agent through waxy starch nanocrystals10. Furthermore, waxy maize-derived amylopectin is a preferred source to restore glycogen in professional athletes2.

Among several genes affecting kernel starch composition, the key genes are amylose extender1 (ae1), dull1 (du1), sugary1 (su1), shrunken2 (sh2) and waxy1 (wx1)9. Waxy maize kernels have a key distinguishing feature where kernels are dull and waxy in appearance imparted by a mutation in Waxy1 (wx1+) gene on the long arm of chromosome 911. Globally, several natural mutant alleles have been identified at the wx1+ locus across diverse Chinese landraces and global collections12,13. The wx1 mutant imparts reduced activity of granule-bound starch synthase-I (GBSS-I), involved in the synthesis of amylose from ADP-glucose14. The wx1 blocks this conversion, leading to enhanced accumulation of amylopectin, sometimes up to 100% in the endosperm, resulting in excellent nutritional and economic values. However, normal maize-based food is deficient in the whole range of essential amino acids, especially, lysine (< 0.25% in flour) and tryptophan (< 0.6% in flour), diminishing the protein quality15. Adding to this significant flaw, humans and other monogastric livestock need supplementation of essential amino acids through diet16. Therefore, malnutrition persists in masses dependent on maize-based foods17. Deficiency of lysine causes systemic protein-energy deficiency, impaired fatty acid metabolism, abnormal absorption of intestinal calcium, and anemia, while the depletion of tryptophan is manifested as impaired skeletal development, reduced growth rate, increased pain sensitivity, and anxiety18. Several approaches like commercial fortification, supplementation, and dietary diversity have been suggested to combat malnutrition, among which crop-biofortification is a safe, sustainable, and socially profitable strategy19.

The mutant Opaque2 (o2+) loci on the short arm of chromosome 7, resulting in a non-functional transcription factor (bZIP family), rebalances the endospermic proteome through reducing zeins, which correspondingly enriches lysine-rich non-zeins20. However, the negative phenotypic effects like chalky endosperm, low test weight, and post-harvest processing challenges associated with o2 were overcome by combining o2 with endosperm and amino acid modifier loci, leading to the development of quality protein maize (QPM)15. The alpha zeins (19 and 22 kDa) regulate the size of protein bodies (PB), while the gamma zeins (27 kDa) regulate the shape and formation of PBs16. The recurrent selection for modifier loci enhanced kernel hardness with increased 27 kDa gamma-zeins in QPM lines16. Therefore, germplasm combining o2 which highly enhances protein quality, with wx1 responsible for increased amylopectin in maize starch, would be a promising resource for alleviating malnutrition through improving the nutritional profile of waxy maize and expanding its application spectrum. The phenotypic effect of multiple gene interactions has been studied for o2/sh2, resulting in collapsed, opaque endosperm, bt2/su1, resulting in shrunken tarnished endosperm, and ae1/su1/su2, resulting in partially wrinkled tarnished endosperm21. However, since wx1 modifies starch composition in maize, while o2 affects the accumulation of PBs, a detailed investigation of the interactive impact on the corresponding nutritional profile and endosperm hardness has remained unexplored.

The specialty maize breeding program in ICAR-Indian Agricultural Research Institute (IARI), New Delhi has developed diverse waxy and QPM maize inbreds by leveraging marker-assisted selected (MAS) across multiple breeding pipelines9. The study was, therefore, formulated to understand (i) the synergistic impact of wx1 and o2 on corresponding quality attributes (lysine, tryptophan, and amylopectin) and (ii) kernel texture (hardness, and visual appearance) in a set of diverse populations developed from several cross combinations, for its application in maize breeding programs.

Materials and methods

Plant materials

The study was conducted on experimental material consisting of populations developed by crossing QPM inbreds viz. PMI-PV5, PMI-PV9 (o2/wx1+; favorable opaque2 allele and unfavorable waxy1 allele), with waxy maize inbreds viz. PMI-waxy-105, PMI-waxy-106, and PMI-waxy-108 (o2+/wx1; with favourable waxy1 allele and unfavourable opaque2 allele). A total of four crosses viz. PMI-PV5 × PMI-waxy-108, PMI-PV9 × PMI-waxy-108, PMI-waxy-106 × PMI-PV9, and PMI-waxy-105 × PMI-PV9 were attempted during spring season 2022 at IARI Experimental Farm, New Delhi (28.63° N, 77.12° E, 229 m MSL). The F1s from these four crosses were grown during the rainy season of 2022 at IARI Experimental Farm, New Delhi, and selfed to generate F2 generation, which was further selfed to derive F2:3 seeds that were used as the base material for the present study.

Selection of F2 genotypes

The four F2 populations derived from crosses viz. PMI-PV5 × PMI-waxy-108 (hereafter Pop1), PMI-PV9 × PMI-waxy-108 (hereafter Pop2), PMI-waxy-106 × PMI-PV9 (hereafter Pop3), and PMI-waxy-105 × PMI-PV9 (hereafter Pop4), were grown at the experimental farm of IIMR-Winter Nursery Centre (WNC), Hyderabad (17°19′ N, 78°25′ E, 542.6 MSL) during winter season of 2023. Genomic DNA was extracted from the leaves of 3-week-old seedlings using the cetyl trimethyl ammonium bromide (CTAB) method22. The populations were screened for o2o2 and wx1wx1 genotypes using gene-based simple sequence repeats (SSR) markers phi057 and phi027, respectively. The nucleotide sequence of primers and bin location were retrieved from the maize genome database (www.maizegdb.org) and the primers were custom synthesized (Sigma Tech., USA). The polymerase chain reactions (PCR) were carried out in a final volume of 20 µl with the primers under the standard protocols followed in the Maize Genetics Unit, Division of Genetics, IARI, New Delhi23. The amplification conditions were as follows: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 5 min, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 45 s, primer annealing ranging between 55 and 60 °C for 45 s, and primer extension at 72 °C for 45 s and a final extension at 72 °C for 8 min. The amplified products were resolved at a voltage of 100 V using 4.0% SeaKem low electroendosmosis agarose gel (Lonza, Rockland, ME, USA)23. The F2 plants homozygous for different classes of o2 and wx1 (o2+o2+/wx1+wx1+, o2o2/wx1+wx1+, o2+o2+/wx1wx1, and o2o2/wx1wx1) were selected from the populations based on genotyping profile (Table 1). Among the o2-based lines, F2:3 kernels with 25–50% opaqueness were selected for further analysis, as is the requirement in the breeding for QPM cultivars. The F2:3 kernels from the three selected homozygous lines (-A, -B, and -C) in each genotypic class were subjected to further experimental studies along with the parents contrasting for opaque2 and waxy1 gene(Table 1).

Analysis of lysine and tryptophan content

The lysine and tryptophan content were estimated based on the protocol standardized by Sarika et al.24, using the UHPLC technique (Dionex Ultimate 3000 System, Thermo Scientific, Massachusetts, USA). Dried seed powder of 20 mg and 30 mg was used for the estimation of lysine and tryptophan, respectively. For lysine, the samples were processed in three steps viz. hydrolysis, neutralization, and derivatization, while in the case of tryptophan, the samples were hydrolyzed followed by the neutralization step only. The mobile phase for lysine consisted of buffer (tetra-methyl ammonium chloride and sodium acetate trihydrate) and organic phase (acetonitrile and methanol) 49:1 (v/v) in the ratio of 9:1 (v/v) and 1:9 (v/v). In the case of tryptophan mobile phase consisted of water and acetonitrile in the ratio of 95:5. Samples were eluted through analytical column Acclaim 120 C18 column (5 μm, 120 Å, 4.6 × 150 mm) having column temperature 25˚C with a flow rate of 1.0 and 0.7 ml/min, and detected using RS 3000 photodiode array (PDA) detector at wavelength 265 and 280 nm, respectively. The samples were analyzed in triplicates. The final concentration of lysine and tryptophan was estimated by standard regression using dilutions of external standards (AAS 18-5ML, Sigma Aldrich).

Analysis of amylopectin content

Amylopectin was estimated by subtracting the percent amylose from 10023. The estimation of amylose content was carried out by the protocol outlined by Redappa et al.25. Well-ground seed powder of 100 mg was taken in triplicates and treated with 500 µl of 80% ethanol. The samples were vortexed and centrifuged for 5 min at 10,000 rpm and the supernatant was separated. The residue of the samples was treated with 500 ul of 0.1 M NaCl solution containing 10% toluene and centrifuge at 10,000 rpm for 5 min. This step was repeated until the supernatant was clear of the white layer. The pellet was cleaned by adding 80% ethanol, and the residue was dried in an incubator at 80 °C for 3–4 h. The obtained residue consists of starch having an impurity of 5%. From the obtained starch 25 mg of residue was taken in a 50 ml tube with an addition of 2.25 ml of 1 M NaOH and 250 µl of 80% ethanol. The sample was incubated in a hot boiling water bath for 15 min with regular mixing. After removing starch, the solution was cooled at room temperature, and the volume made up to 25 ml with distilled water. From that volume, 1.25 ml was taken with the addition of 100 µl 1 M NaOH, 150 µl 1 N acetic acid, and 500 µl KI solution and made up to 25 ml. Absorbance was measured at 620 nm after incubation of 20 min.

Evaluation of kernel hardness properties

The harvested seeds from F2 plants, dried to 11–12% moisture, were analyzed for kernel hardness using TA. HD plus Connect Texture Analyzer (Stable Micro Systems, UK) fitted with a 250 kg load cell using a 30 mm cylindrical probe in compression mode. Fifteen replications were performed for each selected genotype from F2:3 seeds. The force required to impart the initial split in the kernel was recorded in N. The test settings used to record kernel hardness are as follows - test speed: 1 mm/s, trigger force: 0.25 N, travel distance of the probe: 1.5 mm. The force required to break the kernel (hardness) was accessed from the force-displacement curve using software (Exponent Connect Lite, Stable Micro Systems, UK)26.

Statistical analysis

The amplicons were scored as A and B for opaque2 alleles (o2 and o2+) and C and D for waxy1 alleles (wx1 and wx1+) using the software AlphaView v3.3.0 (http://www.cellbiosciences.com). The data was subjected to analysis of variance (ANOVA), descriptive statistics, and least significant difference test (LSD) using packages “stats” and “agricolae”. The ANOVA model on F2 genotypes was carried out following the factorial completely randomized design approach for lysine, tryptophan, and amylopectin. The data was visually represented using “ggplot2” package of R software v.4.2.2.

Results

Genotyping of F2 populations for target genes

The F1 plants developed from the four crosses were verified for heterozygosity using genic SSR markers, phi057 for o2, and phi027 for wx1 alleles. A total of 90–102 plants were obtained in F2 populations across four crosses and were screened for the allelic profile of o2 and wx1. The SSR marker phi057 showed a 165 bp amplicon for the o2 allele and a 153 bp amplicon for the o2+ allele, while marker phi027 produced amplicons of 158 bp for the wx1+ allele and 140 bp for the wx1 allele (Fig. 1). The original gel images of the genotyping are provided in Figure S1 and S2. The populations showed a co-dominant segregation pattern for SSR markers, which segregated in Mendelian segregation pattern of 1:2:1 and 9:3:3:1 for individual locus and combined for o2 and wx1, respectively (p < 0.05) (Table 2). A total of 19, 25, 24, and 23 plants were found to be homozygous for genotypic classes o2+o2+/wx1+wx1+, o2o2/wx1+wx1+, o2+o2+/wx1wx1, and o2o2/wx1wx1 across all the populations. The F2 plants homozygous for genotypic classes o2+o2+/wx1+wx1+, o2o2/wx1+wx1+, o2+o2+/wx1wx1, and o2o2/wx1wx1 across all the populations were selected for evaluation of the segregating effect of o2 and wx1 on lysine, tryptophan, amylopectin and kernel hardness. Kernels from three homozygous plants with the best ear characteristics from each genotypic class across populations were subjected to further studies including estimation of lysine, tryptophan, amylopectin, endosperm opaqueness, and kernel hardness.

Selection for different genotypic classes (a) opaque2 and (b) waxy1 genes in the F2 population of Pop1. Selected homozygous genotypes (1) o2+o2+/wx1+wx1+, (2) o2o2/wx1+wx1+, (3) o2+o2+/wx1wx1, and (4) o2o2/wx1wx1. P1 and P2 represents parents with o2o2/wx1+wx1+ and o2+o2+/wx1wx1 genotype, respectively.

Variation for the lysine and tryptophan among the genotypic classes

The results showed that significant differences (p < 0.01) exist among populations and genotypes within each of the four populations for lysine and tryptophan, with genotypes contributing > 90% of the variation (Table 3). The lysine content ranged between 0.201% (Pop1-o2+/wx1+-C) in Pop1 to 0.394% (Pop1-o2/wx1-A), while the percent tryptophan ranged between 0.026% (Pop1-o2+/wx1+-A) to 0.102% (Pop1-o2/wx1-B) (Table 4). The selected genotypes from population Pop2 recorded lysine content differing between 0.198% (Pop2-o2+/wx1+-A) to 0.393% (Pop2-o2/wx1-B), whereas the tryptophan content ranged between 0.026% (Pop2-o2+/wx1+-A) to 0.95% (Pop2-o2/wx1-A). The genotypes from Pop3 recorded the highest level of lysine at 0.405% (Pop3-o2/wx1-A), and the highest level of tryptophan at 0.113% (Pop3-o2/wx1-C). The genotypes from Pop4 recorded the highest lysine content among all the populations. The highest lysine content in Pop4 ranged between 0.208% (Pop4-o2+/wx1+-B) to 0.415% (Pop4-o2/wx1-A) while the tryptophan content ranged between 0.029% (Pop4-o2+/wx1+-A) to 0.101% (Pop4-o2/wx1-A). The lysine content in QPM parents varied between 0.327% (Pop2-P1-o2/wx1+) to 0.353% (Pop4-P2-o2/wx1+), while the tryptophan content ranged from 0.086% (Pop2-P1-o2/wx1+) to 0.093% (Pop3-P2-o2/wx1+) (Table 4).

Variation for the amylopectin content among the genotypic classes

The ANOVA revealed that the genotypes differed significantly for amylopectin content in populations (Table 3). Overall, the amylopectin differed between 68.9% (Pop2-o2+/wx1+-A) to 99.2% (Pop3-o2/wx1-B). The genotypes in Pop1 recorded amylopectin ranging between 69.3% (Pop1-o2+/wx1+-A) to 98.4% (Pop1-o2/wx1-B) (Table 4), while Pop2 differed for amylopectin content from 68.9% (Pop2-o2+/wx1+-A) to 98.7% (Pop2-o2/wx1-B). The Pop3 recorded the highest level of amylopectin at 99.2% in genotype Pop3-o2/wx1-B, while 70.3% was the lowest in Pop3-o2+/wx1+-A. The genotypes in Pop4 varied for amylopectin content from 69.3% (Pop4-o2+/wx1+-C) to 98.4% (Pop4-o2/wx1-C). Among the parents, the amylopectin ranged from 73.8% (Pop2-P1-o2/wx1+) to 95.9% (Pop1-P2-o2+/wx1) (Table 4).

Association of lysine and tryptophan with o2 and wx1 alleles

The average lysine and tryptophan content in the single mutants o2o2/wx1+wx1+ and wild-type progenies o2+o2+/wx1+wx1+ genotypes were equivalent to the QPM (> 0.25%) and non-QPM (< 0.25%) parents, respectively. However, the lysine and tryptophan differed concerning the presence of homozygous wx1 alleles (Fig. 2a, b). The double mutants were characterized with the average highest amount of lysine (o2o2/wx1wx1: 0.396%) and tryptophan (o2o2/wx1wx1: 0.099%) across crosses, in relation to single mutants (o2o2/wx1+wx1+: lysine: 0.338%, tryptophan: 0.083%) and QPM parents (o2o2/wx1+wx1+: lysine: 0.339%, tryptophan: 0.091%). This trend was also visible in the o2+o2+ progenies segregating for wx1 across populations, where the progenies possessed average higher lysine (o2+o2+/wx1wx1: 0.223%) and tryptophan (o2+o2+/wx1wx1: 0.040%) than progenies with wild-type alleles (o2+o2+/wx1+wx1+: lysine: 0.206%, tryptophan: 0.029%) (Fig. 2a, b). Therefore, the wx1 was found to enhance the lysine and tryptophan content in the population in the background of the o2+o2+ genotypic constitution, thus affecting the nutritional profile of maize.

Association of amylopectin with o2 and wx1 alleles

Across the populations, the amylopectin content in wx1wx1 progenies was significantly higher (> 90%) than in non-waxy (wx1+wx1+) progenies. Furthermore, the wx1wx1 progenies possessed equivalent amylopectin with the waxy parents (> 90%), however, differed in the presence of homozygous o2o2 or o2+o2+ (Fig. 2c). The average amylopectin content was higher in o2o2/wx1wx1 genotypes (98.56%) compared to o2+o2+/wx1wx1 genotypes in F2 (95.20%) and waxy parents (o2+o2+/wx1wx1: 95.40%). The amylopectin content was also found to be higher in o2o2/wx1+wx1+ genotypes (74.66%) than in o2+o2+/wx1+wx1+ genotypes (70.23%) (Fig. 2c). Therefore, the o2 allele was found to enhance the amylopectin content in wx1+wx1+ and wx1wx1 genotypes, leaving a synergistic effect with the wx1 allele.

Variation for kernel physical properties among the genotypic classes

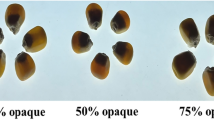

The F2:3 kernels differed for endosperm vitreousness and dullness across the homozygous genotypes. The waxy genotypes (o2o2/wx1wx1 and o2+o2+/wx1wx1) had extremely dull endosperm, restricting the light transmission. However, opaque regions, respective of the selection for 25–50% opaqueness could be observed in the o2o2/wx1wx1 genotypes. The wild-type kernels (o2+o2+/wx1+wx1+) were highly vitreous, while the endosperm was slightly opaque in the o2o2/wx1+wx1+ genotypes (Fig. 3).

Light box-based testing of different homozygous genotypic classes segregating for o2 and wx1. Top row, genotypes selected for white seeds (a) o2+o2+/wx1+wx1+, (b) o2o2/wx1+wx1+, (c) o2+o2+/wx1wx1, (d) o2o2/wx1wx1. Bottom row, genotypes selected for yellow seeds (e) o2+o2+/wx1+wx1+, (f) o2o2/wx1+wx1+, (g) o2+o2+/wx1wx1, (h) o2o2/wx1wx1.

The parents and the different genotypic classes for respective populations revealed differential test performance for endosperm hardness. The force required to impart the first crack in the kernels of the waxy parent ranged between 320.45 N (Pop3-P1-o2+o2+/wx1wx1) to 347.96 N (Pop1-P2-o2+o2+/wx1wx1). The waxy parents (o2+o2+/wx1wx1) recorded higher force for the initial kernel crack than the QPM parents (o2o2/wx1+wx1+), where the average force required to induce the first break in waxy parents was 332.36 N (Fig. 4). The QPM parents could endure only an average of 234.12 N breaking force for the first crack in kernels. Whereas, the wild-type F2:3 grains were the hardest among the populations (mean: 401.28 N), followed by waxy genotypes (mean: 330.99 N) and the double mutant genotypes (mean: 304.28 N). The o2 genotypes showed the least hardness similar to QPM parents requiring an average of 210.96 N force for breaking kernels (Fig. 4). The o2 genotypes segregating for wx1+ differed by an approximate 100 N of break force for kernel hardness, while the double mutant F2:3 genotypes differed by nearly 200 N of break force from the wild type genotypes (o2+o2+/wx1+wx1+). Therefore, the wx1 allele improves kernel hardness in the QPM genotypes (o2o2) (Fig. 4).

Discussion

The distinctive properties of waxy maize conferred by its high amylopectin value due to the wx1 locus, have widened its utilization beyond normal maize in diverse food, textile, pharmaceutical, and coating industries27. A global waxy maize starch SWOT and PESTLE analysis identified that it was valued at US$ 3.68 Bn in 2022. The same report predicts that is expected to reach US$ 6.49 Bn by 2033 at a compound annual growth rate of 5.8% (https://www.transparencymarketresearch.com/). The current climate crisis poses a long-term threat to food security whose effect would be prominent on nutrition. A new report by the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) predicts an addition of 25 million children to the existing victims of malnourishment by 2050 just due to climate change alone28. Waxy maize has many excellent characteristics in terms of its nutritional and economic value, which could be combined with other nutritional quality genes like o2 or conversely to deliver a promising utilization spectrum. Therefore, here we studied the extent of change in lysine, tryptophan, amylopectin, and kernel hardness due to the synergistic action of o2 and wx1.

Assessment of genetic variation for the grain quality traits

The specialty corn breeding program at IARI, New Delhi has identified through MAS and developed diverse waxy maize germplasm through wx1 introgression14. The cereal proteins are limited in lysine (< 2%), which needs to be supplemented to meet the recommended intake set by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. The o2 mutant reorients the amino acid profile through proteome balancing, resulting in enhanced lysine and tryptophan16. The wx1, a natural mutation identified by Emerson and colleagues29, is a locus solely responsible for causing waxy maize development and a promising resource for nutritional quality enhancement9. To leverage the combined effects of these loci, in our study, the elite waxy inbreds were crossed with parents of superior QPM hybrids to combine o2 and wx1 in diverse genotypic classes in F2. The populations segregating for o2 and wx1 displayed significant variation for lysine, tryptophan, amylopectin, and kernel hardness among the four genotypic classes (o2+o2+/wx1+wx1+, o2o2/wx1+wx1+, o2+o2+/wx1wx1, and o2o2/wx1wx1), signifying the differential impact of both the genes individually on the corresponding traits. Compared to normal non-QPM maize (0.25% lysine; 0.06% tryptophan), the extent of lysine in the populations recorded 1.66-fold higher, while there was 1.82-fold higher tryptophan in the double mutants. Similarly, the study also identified a 1.32-fold enrichment of amylopectin in the population against 75% of amylopectin usually found in normal maize. The waxy maize lines with an average of 98% amylopectin, developed from parental inbreds of superior commercial hybrids by Talukder et al.2, showed enhanced germination and seedling vigor performance over normal maize. Since waxy maize is a paramount staple food in many regions of the world, preferred as a vegetable or a breakfast item, and across diverse food segments, the populations of the present study are promising germplasm to alleviate malnutrition and the detrimental effect of climate change.

Effect of o2 and wx1 on lysine and tryptophan in the maize grains

The o2 genotypes (o2o2/wx1+wx1+ and o2o2/wx1wx1) recorded significantly improved levels of lysine and tryptophan than wild-type genotypes (o2+o2+/- -). Most importantly, the recessive o2 mutant, besides its multifarious functions, co-ordinately disrupts the accumulation of zeins and the activity of lysine-ketoglutarate reductase causing reduced transcription levels of concerned genes as low as three times30. Therefore, the lysine content increases due to reduced degradation of lysine and enhanced synthesis of non-zein lysine-rich proteins. Several previous reports on the molecular dissection of o2 mutations agree with the mechanism of protein quality enhancement in maize. Mehta et al.31, Baveja et al.32, and Talukder et al.33, reported reduced expression of o2 in the endosperm at maturity, correlating with enhanced lysine and tryptophan at 40 days after pollination (DAP). The double mutant genotypes from this study having both o2 and wx1 showed highly enhanced lysine and tryptophan content in the endosperm (nearly 2-fold) against single mutant genotypes (o2o2/wx1+wx1+). Interestingly, the waxy mutant genotypes (o2+o2+/wx1wx1) recorded significantly enhanced lysine and tryptophan than wild-type genotypes. The observations follow several similar observations reported by Zhang et al.34, Yang et al.35, and Talukder et al.33. The introgression of o2 in the wx1 background alters the expression of several genes. Wang et al.36, reported differential expression of 14 genes associated with molecular functions (catalytic activity, and signal transducing activity) and 15 genes related to biological processes (including metabolic process, and cellular process) in o2o2/wx1wx1 genotypes compared to single mutants (o2o2/wx1+wx1+). Genes Zm00001d012262.1 (lysine/histidine-specific amino acid transporter), Zm00001d030185.1 (involved in tryptophan metabolism), Zm00001d033483.1 (ZmDHN13 protein), and Zm00001d011063.1 (encodes a sulfur-rich protein) are the key genes specifically upregulated and Zm00001d020984.1, involved in lysine degradation pathway are down-regulated in o2o2/wx1wx1 endosperm compared to o2o2/wx1+wx1+, therefore enhancing lysine biosynthesis and transport35. Enhancement of lysine content in maize was earlier reported to be correlated with transcript levels of elongation factor 1-alpha (EF-1α)37. The gene Zm00001d029385.1, encoding elongation factor 1-alpha (EF-1α) in addition to Zm0001d03471.1, encoding elongation factor 2, were also identified to be upregulated in o2o2/wx1wx1 than in o2o2/wx1+wx1+ genotypes36. Furthermore, wx1 introgression with o2 could modify amino acid profile of the maize endosperm. Genes involved in amino acid transport were also found to be upregulated in previous studies. For example, Zm00001d012262.1 (LHT1 transporter) was upregulated in o2o2/wx1wx1 genotypes. Therefore, this could be associated with enhanced endosperm lysine content based on increased lysine transport36. Zhou et al.4, reported down-regulation of free amino acids (leucine, serine, and alanine) derived from glycolytic intermediates. With the significant reduction in such abundant amino acids in double mutant against wild-type endosperm, the minor amino acids, especially lysine, are predestined to increase. Our study, therefore, phenotypically validates the most probable role of these earlier reported genes.

Accumulation of grain amylopectin across genotypic classes

The higher accumulation of amylopectin in the endosperm is majorly attributed to mutations in the wx1+ gene. The effective utilization of mutant wx1 through MAS resulted in the development of diverse high amylopectin inbreds (recurrent inbreds: HKI161, HKI163, HKI193-1, HKI193-2, Kwi1, Kwi9, and QCL5019) in maize23,33. Respective of the trait, Talukder et al.33, and Zhou et al.4 observed a negative relationship with the expression of wx1 in the mutants at 20, 30, and 40 DAP. The introgression of o2 in the wx1 background not only affects the proteome by affecting prolamin components but also influences the expression of genes involved in the metabolism of amino acids, stress response factors, signal transduction, and interestingly, starch35. The waxy genotypes across the populations had amylopectin content in the 95 to 99% range, which is nearly equivalent to the waxy parents, and approximately 40% higher than non-waxy genotypes (o2o2/wx1+wx1+, o2+o2+/wx1+wx1+) and QPM parents (o2o2/wx1+wx1+). However, in the present study, the double mutants had > 4% amylopectin than single mutants (o2+o2+/wx1wx1). Talukder et al.33, and Sinkangam et al.38, also found that QPM-waxy maize lines had 98.5% amylopectin against 93–96% amylopectin in the waxy lines. Interestingly, we also observed that the o2o2/wx1+wx1+ genotypes also recorded > 6% higher amylopectin than wild-type genotypes. Proteomic analysis in previous reports revealed that introgression of the o2 allele causes changes in starch-protein balance through differential expression of corresponding genes4. The o2 mutation causes regulatory changes in wx1 and affects the transcriptional function of wx1+39. Several starch biosynthesis genes (ADPase: glucose-1-phosphate adenylyltransferase, and SBE IIb: 1,4-α-glucan-branching IIb) showed altered expression in o2o2/wx1wx1 genotypes, where ADPase was upregulated, while SBE IIb was downregulated in o2o2/wx1wx1 genotypes36. Moreover, the double mutant genotypes exhibit reduced intermediate-length α-1,4-linked glucose chains, causing the development of relatively tight linkages between starch granules. Since recessive genes involved in starch, protein, and sugar metabolism, with their interactive genetic effects impart specific phenotypic changes, therefore the enhanced amylopectin in the wx1 introgressed QPM genetic backgrounds could be explained. As SBE IIb is associated with the formation of α-1,6-linkages in glucose, changes in amylopectin content with coordinated relation to changes in expression levels of SBE IIb and GBSS I could be effectively elucidated in o2-wx1 near-isogenic line (NIL) pairs40. Mutation in o2+ was found to affect starch and protein composition, which however can be further well-characterized using NILs40. Moreover, the change in amylopectin in double mutants over single mutants could also be attributed to different modifier loci or QTL governing starch fractions in maize endosperm41.

Synergistic impact of the o2 and wx1 genes on kernel hardness

Grain hardness is a measure of kernel density. In our study, the wild-type genotypes exhibited an average of 21.23%, 83.13%, and 31.87% higher grain hardness over o2+o2+/wx1wx1, o2o2/wx1+wx1+, and o2o2/wx1wx1 genotypes. However, the o2 single mutant genotypes (o2o2/wx1+wx1+) recorded the lowest grain break force (N), indicating the pleiotropic nature of o2 mutation, which includes reduced seed weight, reduced grain yield, unacceptable kernel phenotype (dull, soft, and chalky), greater damage by the stored grain pests, and greater kernel breakage. The reduction in 19- and 22-kD α-zeins in o2o2 genotypes reduces protein body expansion, significantly impacting the tight packaging of starch granules in the protein matrix. However, with the selection for endosperm modification (25-50% opaqueness) in QPM breeding programs, as practiced in the selection of genetic material in the present study, the vitreousness endosperm is majorly contributed by enhanced 27-kD γ-zeins, thus increasing the protein body initiation and therefore, grain hardness4.

The grain hardness of waxy mutants (o2+o2+/wx1wx1 and o2o2/wx1wx1) did not show a wide difference (8.07% on average). Therefore, similar hardness was observed among o2+o2+/wx1wx1 and o2o2/wx1wx1, while a high reduction in grain hardness in o2+o2+/wx1wx1 against wild-type genotypes demonstrates that wx1, besides o2 influences differential grain hardness. In our study, the wx1 allele was found to be positively correlated with kernel hardness in the o2o2 background, which was similarly reported in a previous study by Babu et al.42. Amylopectin is associated with high crystallinity and better highly packed double helices43. Wet milling and starch extraction from amylopectin-rich waxy maize kernels is relatively easier than normal maize44. Another specialty corn, high amylose maize, attributed to ae1 mutation is characterized by very hard high amylose kernels45. Whereas the gelatinization temperature of waxy maize is less, compared to normal maize12, the relationship between gelatinization temperature and kernel hardness is positive, where hard kernels with high amylose content impart higher compaction, and therefore, require more time and energy to gelatinize43. Moreover, the structure of starch granules contains solely amylopectin-rich semi-crystalline regions alternating with amylose-rich amorphous regions also containing c-type amylopectin46. Disruption of the natural structure in waxy maize kernels could additionally contribute to weakened kernels in o2+o2+wx1wx1 genotypes.

Zhou et al.4, reported a closer arrangement of starch granules and compact packaging of starch grains in the protein matrix, giving higher vitreousness in kernels of o2o2/wx1wx1 than o2o2/wx1+wx1+. In o2o2/wx1wx1 germplasm selected for better endosperm vitreousness, the cells accumulate a very large number of smaller protein bodies, imparting more hardness to kernels, similar to the action of increased expression of 27-kDa γ-zein. The scanning electron microscopy by Wang et al.36 found a high density of starch granules in the protein matrix in o2o2/wx1wx1 genotypes compared to the relatively dispersed arrangement found in o2+o2+/wx1wx1 and o2o2/wx1+wx1+. Additionally, the introgression of o2 in the wx1 genotypic background caused starch and proteomic changes, which are yet to be well-characterized at the molecular level4,36. Therefore, the extensive alteration of the endosperm proteome might also upregulate the genes involved in the folding and maintenance of proteins in the endoplasmic reticulum47. Furthermore, the estimation of physiochemical properties of the starch molecules would decipher any changes in the extent of polymerization of components of starch. Therefore, the interactive effect of o2 and wx1 on kernel hardness rendered by any changes in the chain length could be studied from high-performance anion-exchange chromatography (HPAEC), which is an avenue to be explored48.

Utilization of the novel germplasm in the maize quality breeding program

Breeding-based biofortification is an efficient, economically feasible, and environmentally sustainable approach for meeting long-neglected energy needs. In the face of great economic feats, malnutrition is a worldwide concern, such that 88% of countries experience a high level of malnutrition49. Biofortification is associated with 12 of the 17 sustainable development goals, therefore, addressing malnutrition with biofortification results in 16 times of economic benefits50. Several biofortified maize hybrids, developed through diverse breeding approaches across various platforms, are enriched for lysine, tryptophan, provitamin A, and vitamin E9,51. The present study on the effects of o2 and wx1 on lysine, tryptophan, amylopectin, and grain hardness indicates the possibility of independent enhancement of lysine and tryptophan in amylopectin rich waxy maize, unaccompanied by any antagonistic effect between them. With the promise of an expanded utilization spectrum of the waxy maize across diverse industries, breeding for QPM-waxy hybrids is beneficial over the dent/flint corn-based QPM germplasm52. Furthermore, improved cellulosic technologies are currently focused on using maize as an important raw material, besides sugarcane, in bioethanol production which has been placed among the top priorities of the Government of India as an ethanol blending program53. Waxy corn is characterized by higher starch-ethanol conversion efficiency (93.0%) than that of normal corn (88.2%)54. Therefore, with a higher starch-to-glucose conversion ratio in the amylopectin component, waxy maize forms a promising crop for achieving higher biofuel demands.

Conclusions

The study on the effect of o2 and wx1 on quality and kernel physical traits identified the synergistic impact of double mutants leading to significant enrichment of lysine, tryptophan, and amylopectin in the endosperm. The single mutant lines homozygous for o2 and wx1 were correlated with enhanced levels of the essential amino acids and amylopectin. The variation for kernel hardness, associated with genotypic combinations revealed that biofortification efforts for QPM + waxy maize would provide a phenotype that behaves synergistically for quality and kernel hardness as well. The diverse genotypes from this study could be further selected to develop o2 and wx1 NILs to derive appropriate information on the regulatory mechanism in diverse o2+o2+/wx1+wx1+, o2o2/wx1+wx1+, o2+o2+/wx1wx1, and o2o2/wx1wx1 through comprehensive molecular dissection of transcriptome and proteome.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript. The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are provided in the manuscript.

Change history

27 March 2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93287-9

References

FAOSTAT. May (2024). http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QC/visualize (Retrieved 3.

Talukder, Z. A. et al. High amylopectin in waxy maize synergistically affects seed germination and seedling vigour over traditional maize genotypes. J. Appl. Genet. 1-12 https://doi.org/10.1007/s13353-024-00877-w (2024).

Devi, E. L. et al. Microsatellite marker-based characterization of waxy maize inbreds for their utilization in hybrid breeding. 3 Biotech. 7, 316 (2017).

Zhou, Z. et al. Introgression of opaque2 into waxy maize causes extensive biochemical and proteomic changes in endosperm. PLoS One. 11, 8. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0158971 (2016).

Martens, B. M. J., Walter, J. J., Gerrits, E., Henk & MAM, Bruininx. & Schols. Amylopectin structure and crystallinity explains variation in digestion kinetics of starches across botanic sources in an in vitro pig model. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 9, 1–13 (2018).

Li, N. et al. Natural variation in ZmFBL41 confers banded leaf and sheath blight resistance in maize. Nat. Genet. 51 (10), 1540–1548 (2019).

Guo, L., Li, J., Gui, Y., Zhu, Y. & Cui, B. Improving waxy rice starch functionality through branching enzyme and glucoamylase: role of amylose as a viable substrate. Carbohydr. Polym. 230, 115712 (2020).

Obadi, M., Qi, Y. & Xu, B. High-amylose maize starch: structure, properties, modifications and industrial applications. Carbohydr. Polym. 299, 120185 (2023).

Hossain, F. et al. Genetic Improvement of Specialty corn for Nutritional Quality Traits. In Maize Improvement (eds Wani, S.H. et al.) (Springer International Publishing, 2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-21640-4_11.

Li, C., Li, Y., Sun, P. & Yang, C. Starch nanocrystals as particle stabilisers of oil-in‐water emulsions. J. Sci. Food Agric. 94 (9), 1802–1807 (2014).

Huang, B. Q., Tian, M. L., Zhang, J. J. & Huang, Y. Waxy locus and its mutant types in Maize Zea mays L. AGR SCI. CHINA. 9 (1), 1–10 (2010).

Bao, J. D. et al. Identification of glutinous maize landraces and inbred lines with altered transcription of waxy gene. Mol. Plant. Breed. 30, 1707–1714 (2012).

Sun, T. & Wu, X. Structure characteristics of mutation sites in two waxy alleles from Yunnan waxy maize (Zea mays L. var. Certaina Kulesh) landraces. Plos One 18(9), e0291116. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0291116 (2023).

Hossain, F. et al. Molecular analysis of mutant granule-bound starch synthase-I (waxy1) gene in diverse waxy maize inbreds. 3 Biotech. 9, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13205-018-1530-6 (2019).

Prasanna, B. M., Vasal, S. K. & Kassahun, B. Singh, N.N. Quality protein maize. Curr. Sci. 81 (25), 1308–1319 (2001).

Prasanna, B. M. et al. Molecular breeding for nutritionally enriched maize: status and prospects. Front. Genet. 10, 509029 (2020).

Nuss, E. T. & Tanumihardjo, S. A. Quality protein maize for Africa: closing the protein inadequacy gap in vulnerable populations. Adv. Nutr. 2 (3), 217–224 (2011).

Tomé, D. et al. Impact of low protein and lysine-deficient diets on bone metabolism (P08-072-19). Curr. Dev. Nutr. 3, nzz044–P08 (2019).

Lividini, K., Fiedler, J. L., De Moura, F. F., Moursi, M. & Zeller, M. Biofortification: a review of ex-ante models. Glob Food Secur. 17, 186–195 (2018).

Mertz, E. T., Bates, L. S. & Nelson, O. E. Mutant gene that changes protein composition and increases lysine content of maize endosperm. Science 145 (3629), 279–280. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.145.3629.279 (1964).

Boyer, C. D. & Hannah, L. C. Kernel mutants of corn. In Specialty Corns (Hallauer, A.R.) (CRC, Boca Raton, Florida, 2000). https://doi.org/10.1201/9781420038569.

Murray, M. G. & Thompson, W. Rapid isolation of high molecular weight plant DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 8 (19), 4321–4326 (1980).

Talukder, Z. A. et al. Enrichment of amylopectin in sub-tropically adapted maize hybrids through genomics-assisted introgression of waxy1 gene encoding granule-bound starch synthase (GBSS). J. Cereal Sci. 105, 103443 (2022).

Sarika, K. et al. Exploration of novel opaque16 mutation as a source for high lysine and tryptophan in maize endosperm. Indian J. Genet. 77 (01), 59–64 (2017).

Reddappa, S. B. et al. Development and validation of rapid and cost-effective protocol for estimation of amylose and amylopectin in maize kernels. 3 Biotech. 12 (3), 62 (2022).

Onyango, C., Mutungi, C., Unbehend, G. & Lindhauer, M. G. Rheological and textural properties of sorghum-based formulations modified with variable amounts of native or pregelatinised cassava starch. LWT - Food Sci. Technol. 44 (3), 687–693 (2011).

Xie, A. J., Li, M. H., Li, Z. W. & Yue, X. Q. A preparation of debranched waxy maize starch derivatives: Effect of drying temperatures on crystallization and digestibility. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 264, 130684 (2024).

Global food policy report. International Food Policy Research Institute. Food Systems for Healthy Diets and Nutrition (International Food Policy Research Institute, 2024). https://hdl.handle.net/10568/141760

Emerson, R. A., Beadle, G. W. & Fraser, A. C. A summary of linkage studies in maize. (1935).

Hurst, J. P. et al. Editing the 19 kDa alpha-zein gene family generates non‐opaque2‐based quality protein maize. Plant. Biotechnol. J. 22 (4), 946–959 (2024).

Mehta, B. K. et al. Expression analysis of β-carotene hydroxylase1 and opaque2 genes governing accumulation of provitamin-A, lysine and tryptophan during kernel development in biofortified sweet corn. 3 Biotech. 11 (7), 325 (2021).

Baveja, A. et al. Expression analysis of opaque2, crtRB1 and shrunken2 genes during different stages of kernel development in biofortified sweet corn. J. Cereal Sci. 105, 103466 (2022).

Talukder, Z. A. et al. Recessive waxy1 and opaque2 genes synergistically regulate accumulation of amylopectin, lysine and tryptophan in maize. J. Food Compos. Anal. 121, 105392 (2023).

Zhang, W. L. et al. Increasing lysine content of waxy maize through introgression of opaque-2 and opaque-16 genes using molecular assisted and biochemical development. PLoS One. 8, e56227. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0056227 (2013).

Yang, Q. et al. CACTA-like transposable element in ZmCCT attenuated photoperiod sensitivity and accelerated the postdomestication spread of maize. PNAS 110 (42), 16969–16974 (2013).

Wang, W. et al. Molecular mechanisms underlying increase in lysine content of waxy maize through the introgression of the opaque2 allele. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20, 684. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20030684 (2019).

Carneiro, N. P., Hughes, P. A. & Larkins, B. A. The eEFlA gene family is differentially expressed in maize endosperm. Plant. Mol. Biol. 41, 801–814. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1006391207980 (1999).

Sinkangam, B. et al. Integration of quality protein in waxy maize by means of simple sequence repeat markers. Crop Sci. 51, 2499–2504 (2011).

Li, X. Y. & Liu, J. L. The effects of maize endosperm mutant genes and gene interactions on kernel components II. The interactions of o2 with su1, sh2, bt2 and wx genes. Acta Agron. Sin. 19, 460–467 (1993).

Zhang, Z., Zheng, X., Yang, J., Messing, J. & Wu, Y. Maize endosperm-specific transcription factors O2 and PBF network the regulation of protein and starch synthesis. PNAS 113 (39), 10842–10847 (2016).

Lin, F. et al. QTL mapping for maize starch content and candidate gene prediction combined with co-expression network analysis. Theor. Appl. Genet. 132, 1931–1941 (2019).

Babu, B. K., Agrawal, P. K., Saha, S. & Gupta, H. S. Mapping QTLs for opaque2 modifiers influencing the tryptophan content in quality protein maize using genomic and candidate gene-based SSRs of lysine and tryptophan metabolic pathway. Plant. Cell. Rep. 34, 37–45 (2015).

Dominguez-Ayala, J. E., Ayala-Ayala, M. T., Velazquez, G., Espinosa-Arbelaez, D. G. & Mendez-Montealvo, G. Crystal structure changes of native and retrograded starches modified by high hydrostatic pressure: physical dual modification. Food Hydrocoll. 140, 108630 (2023).

Dorantes-Campuzano, M. F. et al. Effect of maize processing on amylose-lipid complex in pozole, a traditional Mexican dish. Appl. Food Res. 2 (1), 100078 (2022).

Reddappa, S. B. et al. Genetic Analysis of Accumulation of Amylose and resistant starch in Subtropical Maize hybrids. Starch-Stärke 76, 2300147. https://doi.org/10.1002/star.202300147 (2024).

Dome, K., Podgorbunskikh, E., Bychkov, A. & Lomovsky, O. Changes in the crystallinity degree of starch having different types of crystal structure after mechanical pretreatment. Polymers 12 (3), 641 (2020).

Kirst, M. E., Meyer, D. J., Gibbon, B. C., Jung, R. & Boston, R. S. Identification and characterization of endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation proteins differentially affected by endoplasmic reticulum stress. Plant. Physiol. 138 (1), 218–231 (2005).

Chen, F. et al. The underlying physicochemical properties and starch structures of indica rice grains with translucent endosperms under low-moisture conditions. Foods 11 (10), 1378. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods11101378 (2022).

Global Nutrition Report. Shining a Light to spur Action on Nutrition (Development Initiatives, 2018).

Global food policy report. Food Systems for Healthy Diets and Nutrition (International Food Policy Research Institute, 2016).

Katral, A. et al. Enrichment of kernel oil and fatty acid composition through genomics-assisted breeding for dgat1-2 and fatb genes in multi-nutrient rich maize. Plant J. 119, 2402–2422. https://doi.org/10.1111/tpj.16926 (2024).

Mishra, S.J. et al. Genomics-assisted stacking of waxy1, opaque2, and crtRB1 genes for enhancing amylopectin in biofortified maize for industrial utilization and nutritional security. Funct. Integr. Genomics. 25, 18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10142-024-01523-8 (2025).

Sarwal, R. et al. Roadmap for Ethanol Blending in India 2020-25. NITI Aayog. Ministry of Petroleum and Natural Gas (Government of India, 2021).

Yangcheng, H., Jiang, H., Blanco, M. & Jane, J. L. Characterization of normal and waxy corn starch for bioethanol production. J. Agric. Food Chem. 61 (2), 379–386 (2013).

Acknowledgements

Division of Genetics, ICAR-IARI, New Delhi is duly acknowledged for providing the required field and lab facilities for undertaking the work.

Funding

This research was funded by DBT-NER project on Marker-assisted introgression of waxy1 allele for development of high amylopectin maize genotypes Grant No. [BT/PR25257/NER/95/1101/2017], and CRP-MB funded project on Molecular breeding for improvement of tolerance to biotic and abiotic stresses, yield and quality traits in crops-Maize component grant number [12-143 C]”.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization V.M. and F.H.; Methodology, S.J.M., I.G., R.U.Z., G.C., A.K.V.T., Z.A.T.; Software, R.U.Z., and I.G.; Validation, S.J.M.; Formal Analysis, S.J.M., and I.G.; Investigation, S.J.M.; Resources, F.H., and V.M.; Data Curation, S.J.M., and V.M.; Writing – Original Draft Preparation, S.J.M., and I.G.; Writing – Review & Editing, V.M., and F.H.; Visualization, I.G., V.M., F.H.; Supervision, V.M., F.H., and J.K.; Project Administration, V.M., F.H., E.L.D., and K.S.; Funding Acquisition, F.H. and V.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this Article was revised: The original version of this Article contained an error in the Figure 3 legend. It now reads: “Light box-based testing of different homozygous genotypic classes segregating for o2 and wx1. Top row, genotypes selected for white seeds (a) o2+o2+/wx1+wx1+, (b) o2o2/wx1+wx1+, (c) o2+o2+/wx1wx1, (d) o2o2/wx1wx1. Bottom row, genotypes selected for yellow seeds (e) o2+o2+/wx1+wx1+, (f) o2o2/wx1+wx1+, (g) o2+o2+/wx1wx1, (h) o2o2/wx1wx1.”

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mishra, S.J., Gopinath, I., Muthusamy, V. et al. Unraveling the interactive effect of opaque2 and waxy1 genes on kernel nutritional qualities and physical properties in maize (Zea mays L.). Sci Rep 15, 3425 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87666-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87666-5