Abstract

The objective of this study was to identify and characterize the fungal pathogens responsible for wilt diseases in solanaceous crops, specifically tomato, brinjal, and chili, in the Kashmir valley. Through both morphological and molecular analyses, including DNA barcoding of the ITS, TEF, RPB1, and RPB2 genomic regions, Fusarium incarnatum and Fusarium avenaceum were identified as the primary causal agents of wilt in tomato and brinjal, and chili, respectively. Pathogenicity tests confirmed the virulence of these pathogens, with typical wilt symptoms observed upon inoculation. This represents the first report of F. incarnatum and F. avenaceum as wilt pathogens in solanaceous crops in India. Phylogenetic analysis further confirmed the genetic variability of these pathogens, revealing their expanding host range. The findings underscore the growing adaptability of these Fusarium species to diverse agricultural systems and highlight the urgent need for targeted disease management strategies to mitigate the significant yield losses caused by Fusarium wilt in solanaceous vegetable production.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The family Solanaceae comprises several economically important flowering plants, including crops that serve various purposes such as food, medicine, and ornamentals. Among the most significant solanaceous vegetables are tomato, eggplant, and pepper, which are known for their numerous health benefits1. However, these crops are highly susceptible to a range of diseases, with fungal wilt being one of the most destructive, both in terms of incidence and yield loss2. In India, wilt disease in solanaceous crops has emerged as a severe threat, with disease incidence ranging from 5 to 93%, and yield losses between 45 and 60% due to the invasion of Fusarium pallidoroseum in the Kashmir valley3. Notably, Fusarium solani sp. melongenae has been confirmed as the causal agent of wilt in brinjal in Jammu and Kashmir4, and several other Fusarium species, including Fusarium chlamydosporum, Fusarium equiseti, and Fusarium flocciferum, have been recently reported as pathogens in chili and brinjal in the Kashmir region5,6. The occurrence of wilt disease in the Kashmir valley has been frequent, leading to yield losses ranging from 11.67 to 96.67%7. Fusarium wilt has thus become a major concern in solanaceous crops, especially as the pathogens responsible have diversified across different host species. The current study focuses on the incursion of these wilt-causing pathogens in the Kashmir valley, particularly the movement of Fusarium species between various host crops. Traditional identification of Fusarium pathogens based on morphological features, such as macroconidia, microconidia, and chlamydospores, has been insufficient due to the complex nature of the Fusarium genus8,9. Thus, DNA sequence-based identification has become an invaluable tool for accurately identifying Fusarium species. Molecular techniques, such as DNA barcoding using the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) and translation elongation factor (TEF) genomic regions, as well as the RPB1 and RPB2 genes, have provided clearer insights into the diversity of these pathogens8,10. Previous studies have used ITS as a DNA barcoding marker to identify Fusarium species, but it has been noted that ITS may not be reliable for closely related species11. Consequently, conserved genes like TEF have been increasingly employed for phylogenetic analyses in combination with ITS to better resolve species relationships12. For instance, the TEF gene has proven effective in distinguishing subspecies and has been used by several researchers to clarify species identities within the Fusarium genus11,13,14. In this investigation, we identified Fusarium avenaceum as the predominant wilt-causing pathogen in chili and Fusarium incarnatum as the primary pathogen in brinjal and tomato. This finding represents a new report of F. incarnatum and F. avenaceum as causal agents of wilt in solanaceous crops in India. The increasing rate of pathogen invasions, exacerbated by changes in agricultural practices, habitat disturbances, climate change, and pathogen introduction through trade, further complicates the management of these diseases. This study contributes to the understanding of Fusarium species’ geographical spread and their potential for cross-host infection in solanaceous crops.

Material and methods

Sample collection and maintenance of cultures

Diseased plants of chili, tomato, and brinjal, showing typical symptoms of wilt disease, were collected from different districts of the Kashmir region, including Pulwama, Srinagar, Baramulla, and Anantnag, during July and August 2020. Samples were randomly selected from various districts of the Kashmir valley. The tissue bit technique was used to isolate the fungus from the infected samples, which were then purified using the single-spore technique. The pure cultures obtained were maintained at 25 °C ± 1 °C and stored at 4 °C15.

Morphological and cultural characteristics of the isolated pathogen(s)

The pathogens were cultured on Potato Dextrose Agar (PDA) medium at 25 °C to obtain pure cultures, which were then subjected to morphological studies. Cultures that were 10–15 days old were used to prepare semi-permanent slides for microscopic observation. The key characteristics examined included the shape, size, and septation of microconidia, macroconidia, and mycelium.

Identification and pathogenicity test

The pathogens were identified based on their pathological and morphological characteristics. Seedlings of chili (cv. Kashmir Long-1), tomato (cv. Shalimar Hybrid Tomato-1), and brinjal (cv. Local Long) were uprooted and transplanted into the infected potting mixture. The plants were continuously monitored for symptom development until they eventually died, thereby fulfilling Koch’s postulates15,16.

DNA extraction

For DNA extraction, mycelia were crushed in 400 µl of extraction buffer using a mortar and pestle, and the resulting slurry was incubated at 65 °C for 1 h. After the addition of RNase and a subsequent incubation, sodium acetate was introduced, and the sample was chilled. The lysate was then centrifuged, and DNA was precipitated with isopropanol, pelleted, washed with 70% ethanol, air-dried, and resuspended in Tris–EDTA buffer.

PCR amplification

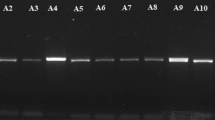

For PCR amplification, a 25 μl reaction mixture was prepared, with an initial denaturation at 95 °C for 8 min, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 15 s, annealing based on primer Tm, first extension at 72 °C for 1 min and a final extension at 72 °C for 25 min. PCR products were run on a 1% agarose gel with SYBER green dye in 1 × TAE buffer, visualized with a gel documentation system, and compared to a 100 bp DNA ladder. Amplified products from ITS, TEF, RPB1, (Tables 1, 2 and 3) and RPB2 primers were sequenced by Bionivid Technology for DNA barcoding to analyze genetic variability.

Sequencing and DNA barcoding

Amplified PCR products using ITS1F2 / ITS4R2 and TEF Fu3 F/ TEF Fu3, RPB1 and RPB2 were outsourced to Bionivid Technology [P] Limited, Bangalore. The genetic variability among collective samples was ascertained through DNA barcoding of ITS, TEF, RPB1 and RPB2 regions. A dendrogram was constructed using Cluster W software.

Results

Tomato and brinjal plants showing wilt symptoms were collected from various regions of Kashmir, including Anantnag, Srinagar, Pulwama, and Baramulla, during July and August 2020. The observed symptoms included yellowing of the plant, lesions on the roots and stems, and wilting or death of the plant. The collected samples were isolated on PDA medium, and pure cultures were maintained at 25 ± 1 °C and stored at 4 °C (Fig. 1a).

Morpho-cultural identification

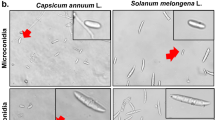

To identify the pathogen on the host, pure cultures were established on PDA medium, and both were analyzed based on their morphological characteristics. The key features studied included the shape, size, and septation of microconidia, macroconidia, and mycelium (Table 4). Fusarium incarnatum, isolated from tomato and brinjal, initially produced white colonies that gradually turned yellow at the agar base, with a growth of 90 mm after 18 days of incubation at 25 ± 1 °C. Microscopic observations revealed that the mycelium was branched and cylindrical, with a width of 3.20–4.20 µm. Microconidia were single-celled, hyaline, with 0–1 septa, and measured 10–12 × 3–4 µm. Macroconidia were sickle-shaped, hyaline, 4–5 septate, and measured 28–31 × 3–5 µm. Fusarium avenaceum, isolated from the chili host, initially produced white colonies that gradually turned brownish-yellow at the agar base. The fungal culture reached a growth of 90 mm after 18 days of incubation at 25 ± 1 °C. The average measurements indicated that the mycelium was branched and cylindrical, measuring 53–4.98 µm in diameter. Microconidia were curved, hyaline, with 0–2 septa, and measured 11–20.2 µm × 4–5 µm. Macroconidia were curved, hyaline, with 5–7 septa, and measured 49.9–78 × 3.6–4.7 µm (Fig. 1b).

Pathogenicity test

The seedlings of chili (cv. Kashmir Long-1), tomato (cv. Shalimar Hybrid Tomato-1), and brinjal (cv. Local Long) were potted in the greenhouse. Fusarium incarnatum, obtained from the respective crop plant, was used to infect the same potted plant to fulfill Koch’s postulates17,18. The incubation period for Fusarium incarnatum was recorded as four weeks for symptom development, while F. avenaceum took six weeks for symptom appearance (Fig. 2). Infected plants exhibited initial symptoms, with leaves discoloring from light green to yellow, followed by drooping, shriveling, and eventually death. The collar region of the plants was cut vertically, revealing brownish spots and discoloration in the vascular bundles, indicating wilt as the cause of death. The pathogens were re-isolated and inoculated from all infected plants. These were compared with the original pure culture inoculates, and the re-isolates resembled the original cultures based on morphological, cultural, and pathogenic characteristics.

DNA Extraction PCR amplification

DNA extraction of isolates followed by PCR amplification was performed for ITS1 and ITS4, TEF, RPB1 and RPB2 primer pairs, and the amplified products were run on 1% agarose gel (Fig. 3a–c). Amplified PCR products were outsourced for sequencing to Bionivid Technology [P] Limited, Bangalore. BLAST was used to find regions of similarity between the query sequence and the sequence present in the NCBI (www.ncbi.nlm.in) database. The sequences were successfully submitted and Accessioned in GenBank (Table 5). Fusarium incarnatum and Fusarium avenaceum have been first time reported as wilt pathogens of solanaceous host crops (Table 6).

Phylogenetic analysis

A dendrogram was generated using Cluster W software. The phylogenetic analysis using ITS, TEF and RPB1, RPB2 sequences were carried out (Fig. 4).

Discussion

The major solanaceous vegetable crops include tomato, eggplant, chili, and pepper1. These crops offer numerous health benefits and help combat various diseases. However, the most devastating disease, which is becoming increasingly widespread, is wilt, particularly in terms of incidence and yield loss. Fusarium wilt leads to 50–80% yield losses annually8. In the present study, fungi associated with wilt in tomato and brinjal were identified as Fusarium incarnatum, while Fusarium avenaceum was identified as the pathogen in chili, based on both morphological and molecular characteristics of the pathogens19. When artificially inoculated using the single-spore technique on the respective hosts, with rhizosphere inoculation on wilted plants, the fungal pathogens isolated from wilted plants exhibited typical disease symptoms. The plants developed initial symptoms by the second week of inoculation. The plants showed complete wilting, beginning with light green to yellowish discoloration of the leaves, followed by drooping, shriveling, and, finally, death of the entire plant by the sixth week of inoculation. Upon vertical cutting of the collar region, the vascular bundles showed brownish discoloration.

Amplification of the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region using genus- and species-specific ITS primers identified Fusarium incarnatum and Fusarium avenaceum using primer combinations such as K-Lab-FusOxy-ITS1F2 and Lab-FusOxy-ITS4R2. To further confirm these results, transcription elongation factor (TEF Fu3) amplification was performed with the TEF primer combination (TEF-Fu3-F and TEF-Fu3-R), as well as RPB1 and RPB2 genes. The PCR products of the ITS1-5.8S-ITS4 region, TEF Fu3, and RPB1 and RPB2 genes were sequenced, and the pathogens identified through sequencing were published in GenBank. Sequence alignment using Cluster W revealed that the similarity level among sequences was independent of their geographical origin20,21. Furthermore, Fusarium incarnatum has previously been reported in crops such as sorghum, rice, maize, and bell pepper, while Fusarium avenaceum has been identified in wheat and soybean22,23. In solanaceous crops, these species have been identified as wilt pathogens for the first time in India and the World, highlighting the diversifying nature of F. incarnatum and F. avenaceum with respect to their host crops, both within solanaceous crops and other host crops. In the phylogenetic study, the ITS, TEF, RPB1, and RPB2 genes were grouped into four distinct clusters. Sequences were compared with their respective hits retrieved from the NCBI database.

Conclusion

This study provides significant insights into the fungal pathogens causing wilt in major solanaceous crops, identifying Fusarium incarnatum and Fusarium avenaceum as the causal agents in tomato, brinjal, and chili, respectively. These findings were confirmed through morphological analysis, molecular characterization using ITS, TEF, RPB1, and RPB2 gene markers, and pathogenicity testing via artificial inoculation. The phylogenetic analysis and sequencing revealed that these pathogens, though previously reported in other crops like sorghum, rice, maize, wheat, and soybean, are reported for the first time in solanaceous crops in India. This highlights the expanding host range of F. incarnatum and F. avenaceum, suggesting their evolving adaptability to diverse agricultural systems. The study emphasizes the need for ongoing research and monitoring of Fusarium species to understand their host specificity, geographical distribution, and impact on solanaceous crops. Such efforts are crucial for developing targeted management strategies to mitigate the devastating yield losses caused by Fusarium wilt in solanaceous vegetable production.

Data availability

The sequencing data is available on the NCBI database. The sequence of ITS with accession numbers OM189449, OM189460, OM189456 were successfully deposited in GenBank (www.ncbi.nlm.in). The sequence of TEF has been provided Accession Numbers OM441190, OM441201, and OM441197 were successfully deposited in GenBank www.ncbi.nlm.in. The sequence of RPB1 and RPB2 with accession numbers OR484033, OR484034, OR484035, OR484036, OR640336 and OR640337 were successfully deposited in GenBank www.ncbi.nlm.in. The Fungal material was formally identified by Dr. Zahoor Bhat Plant Pathologist and Dr. Khalid Z. Masoodi Plant Biotechnologist. No voucher specimen is required to be deposited in a publicly accessible herbarium for this study.

References

Morris, W. & Taylor, M. The solanaceous vegetable crops: Potato, tomato, pepper, and eggplant. (2017).

Manda, R. R., Addanki, V. A. & Srivastava, S. Bacterial wilt of solanaceous crops. Int. J. Chem. Stud 8(6), 1048–1057 (2020).

Naik, M., Rani, G. & Madhukar, H. Identification of resistant sources against wilt of chilli (Capsicum annuum L.) caused by Fusarium solani (Mart.) Sacc. J. Mycopathol. Res 46(1), 93–96 (2008).

Lolpuri, Z., Management of fungal wilt complex of brinjal (Solanum melongena L.). Sc.(Ag.) Thesis, SK University of Agricultural Science and Technology. Kashmir, 63, (2002).

Parihar, T. J. et al. Fusarium chlamydosporum, causing wilt disease of chili (Capsicum annum L.) and brinjal (Solanum melongena L.) in Northern Himalayas: A first report. Sci. Rep. 12(1), 20392 (2022).

Parihar, T. J., et al., Fusarium flocciferum, causing wilt disease of chili (Capsicum annuum L.) in Northern Himalayas: A first report. Plant Disease, (2023).

WANI, A.H., Biological control of wilt of brinjal caused by Fusarium oxysporum with some fungal antagonists. Indian Phytopathology, 2012. 58(2): p. 228–231.

Hami, A. et al. Morpho-molecular identification and first report of Fusarium equiseti in causing chilli wilt from Kashmir (Northern Himalayas). Sci. Rep. 11(1), 3610 (2021).

O’Donnell, K. et al. DNA sequence-based identification of Fusarium: A work in progress. Plant Disease 106(6), 1597–1609 (2022).

Schoch, C. L. et al. Nuclear ribosomal internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region as a universal DNA barcode marker for Fungi. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 109(16), 6241–6246 (2012).

O’Donnell, K. et al. DNA sequence-based identification of Fusarium: Current status and future directions. Phytoparasitica 43, 583–595 (2015).

Ramdial, H. et al. Phylogeny and haplotype analysis of fungi within the Fusarium incarnatum-equiseti species complex. Phytopathology 107(1), 109–120 (2017).

Dita, M. A. et al. A molecular diagnostic for tropical race 4 of the banana Fusarium wilt pathogen. Plant pathology 59(2), 348–357 (2010).

Divakara, S. T. et al. Molecular identification and characterization of Fusarium spp. associated with sorghum seeds. J. Sci. Food Agric. 94(6), 1132–1139 (2014).

Ferniah, R. S. et al. Characterization and pathogenicity of Fusarium oxysporum as the causal agent of fusarium wilt in chili (Capsicum annuum L.). Microbiol. Indonesia 8(3), 5 (2014).

Davey, C. & Papavizas, G. Comparison of methods for isolating Rhizoctonia from soil. Can. J. Microbiol. 8(6), 847–853 (1962).

Sridhar, K., Rajesh, V. & Omprakash, S. A critical review on agronomic management of pests and diseases in chilli. Int. J. Plant Anim. Environ. Sci 4, 284–289 (2014).

Thomas, S., Kumar, D. & Ali, A. Marketing of Green Chilli in Kaushambi District of Uttar Pradesh, India. Int. J. Scientific Engin. Res., 47–48 (2015).

Booth, C., The genus Fusarium commonwealth mycological institute. Kew, Surrey, 237, (1971)

Ramdial, H., Hosein, F. & Rampersad, S. First report of Fusarium incarnatum associated with fruit disease of bell peppers in Trinidad. Plant Disease 100(2), 526–526 (2016).

Gupta, R. Foodborne infectious diseases. In Food Safety in the 21st Century, 13–28, (Elsevier, 2017)

Uhlig, S., Jestoi, M. & Parikka, P. Fusarium avenaceum—the North European situation. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 119(1–2), 17–24 (2007).

Chang, K. et al. First report of Fusarium proliferatum causing root rot in soybean (Glycine max L.) in Canada. Crop Protection 67, 52–58 (2015).

Acknowledgements

The cost of consumables and research incurred in the investigation was funded by PURSE grant and DST-SERB funding (SR/PURSE/2022/124) and CRG/2022/000207 to Dr. Khalid Z. Masoodi. We thank Dr. Zahoor A. Bhat, Professor, Division of Plant Pathology, SKUAST-Kashmir for Morphological identification and Prof. Nayeema Jabeen, Head, Division of Vegetable Science, SKUAST-Kashmir for providing vegetable seeds.

Funding

The cost of consumables incurred and equipment used in the investigation were funded by DST-PURSE grant and DST-ANRF, funding (SR/PURSE/2022/124) and CRG/2022/000207 to Dr. Khalid Z. Masoodi.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Funding acquisition K.Z.M. conceptualization K.Z.M. methodology, T.J.P. Supervision, K.Z.M. formal analysis, K.Z.M. data curation, T.J.P, K.Z.M, writing-original draft preparation, T.J.P, M.N. Bioinformatic analysis, K.Z.M, Review and editing K.Z.M., T.P., S.M., S.I.H., M.P., I.A.M., T.A., N.G., All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Molecular identification was done by Dr. K.Z. Masoodi. Voucher specimen have been deposited at K-Lab pathogen repository Division of Plant Biotechnology, SKUAST-K, Shalimar. The experimental research and field studies were carried out in the present investigation and plant collections are in accordance with local legislation and comply with institutional, national, and international guidelines.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Parihar, T.J., Naik, M., Mehraj, S. et al. Emergence of Fusarium incarnatum and Fusarium avenaceum in wilt affected solanaceous crops of the Northern Himalayas. Sci Rep 15, 3855 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87668-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87668-3