Abstract

Acoustical properties are essential for understanding the molecular interactions in fluids, as they influence the physicochemical behavior of liquids and determine their suitability for diverse applications. This study investigated the acoustical parameters of silver nanoparticles (Ag NPs), reduced graphene oxide (rGO), and Ag/rGO nanocomposite nanofluids at varying concentrations. Ag NPs and Ag/rGO nanocomposites were synthesized via a Bos taurus indicus (BTI) metabolic waste-assisted method and characterized using advanced techniques, including XRD, TEM, Raman, DLS, zeta potential, and XPS. The synthesized nanocomposites were evaluated for their acoustical, antioxidant, and plant growth-regulatory properties. Acoustical analysis revealed a linear relationship between the nanofluid concentration and density, with key parameters such as adiabatic compressibility, apparent molar compressibility, and apparent molar volume increase at lower concentrations. Irregular changes in ultrasonic velocity and other parameters at 0.025 mol/dm3 suggest unique nanoparticle-solvent interactions. The Ag/rGO nanocomposites exhibited superior antioxidative potential compared to Ag NPs, with DPPH scavenging activity reaching 65.69% and ABTS scavenging activity reaching 65.01% at 100 µg/mL. Plant growth studies have demonstrated enhanced germination rates (100% in spinach and 40% in fenugreek) and improved root and shoot elongation at 0.0025–0.005 mol/dm3. This study bridges the gap in understanding the acoustical and multifunctional properties of nanocomposites for biomedical, agricultural, and environmental applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nanofluids, a revolutionary class of colloidal mixtures, have transformed the landscape of industrial and technological applications owing to their exceptional thermophysical properties1. These fluids, which are composed of nanoparticles dispersed in base liquids such as water or oils, exhibit significant enhancements in heat transfer, thermal conductivity, and viscosity1,2. Such attributes overcome the limitations of traditional base and bulk fluids, enabling their use in a broad spectrum of applications including electronics cooling3,4,5, air conditioning6, nuclear reactor systems7, and biomedical fields8,9,10. Although extensive research has focused on the thermophysical properties of nanofluids, their acoustical properties remain relatively unexplored.

Acoustics, the study of sound wave propagation, provides insights into molecular interactions, structural dynamics, and physicochemical changes within liquid mixtures11,12,13. These investigations are fundamental for understanding and optimizing the behavior of nanofluids in advanced technological applications such as ultrasonic imaging and sound absorption14. While the potential of nanotechnology has led to significant advancements in ultrasonics and the introduction of novel materials and devices for ultrasound-based investigations, the study of acoustical properties in nanomaterials remains an emerging field. For instance, Thirumaran and Jayalakshmi studied the molecular interactions of n-alkanols with cyclohexane and DMF at 303 K, demonstrating the value of such investigations15. Similarly, studies on the acoustical properties of Ag NPs16 and CuO NPs17 in aqueous solutions of various glycols highlight the growing interest in this area. These studies underscore the relevance of acoustical investigations for understanding the interaction mechanisms and physicochemical behaviors of nanomaterials. Despite the potential for these applications, systematic studies on the acoustical properties of nanomaterials, especially functional nanocomposites, are limited.

In recent years, bio-inspired approaches to synthesize nanomaterials have gained attention because of their eco-friendliness and cost-effectiveness. Leveraging biological resources as reducing agents offers a sustainable alternative to conventional chemical synthesis that often involves hazardous substances and energy-intensive processes18. Bos taurus indicus (BTI) metabolic waste has been proven to be a potent reducing and stabilizing agent because of its rich composition of urea, creatinine, uric acid, and other bioactive compounds19. Our research group has previously employed this biological resource for synthesizing various nanomaterials, including Ag NPs20, Pd NPs21, Au NPs19, Co2O4 NPs22, CuO NPs23, Ag/rGO nanocomposites24 and trimetallic NPs25. These materials have demonstrated significant potential for applications in catalysis, biomedicine, and environmental remediation19,20,21,22,23,24,25.

This study presents a modified synthesis of Ag/rGO nanocomposites using BTI metabolic waste. Unlike previous methods19,20,21,22,23,24,25, which rely on the surfactant cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) for stabilization, this approach eliminates CTAB to address its known toxicity, ensuring a safer and greener synthesis pathway. The resulting nanocomposites exhibited enhanced dispersion and stability, opening avenues for their application in catalysis, diagnostics, and sustainable agriculture. Additionally, the antioxidant potential of the Ag/rGO nanocomposites, initially explored through the ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP) assay, was further evaluated using a suite of methods, including ferrous ion chelating activity (FICA), DPPH, and ABTS assays. These comprehensive evaluations provided valuable insights into their antioxidative efficacy and potential biomedical applications. By systematically investigating the acoustical properties of Ag NPs, rGO, and their nanocomposites across various concentration ranges, this study aims to advance the understanding of nanomaterial behavior in sound wave propagation and its implications for applications in catalysis, diagnostics, and nanodrug delivery. This work bridges critical knowledge gaps and highlights the transformative potential of bio-inspired nanomaterials in addressing contemporary challenges across the biomedical, environmental, and agricultural domains.

Materials and methods

Chemicals

Chemicals supplied by SD Fine Chemicals, India Ltd., and procured through Unique Biological Pvt. Ltd., Kolhapur, included sulfuric acid (H2SO4, 98%), potassium permanganate (KMnO4, 99.5%), graphite flakes (size 100 microns, 99.5%), ethanol (99%), cetyl-trimethyl ammonium bromide (CTAB, 99%), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2, 30% w/v), phosphoric acid (H2PO4, 85%), hydrochloric acid (HCl, 36.5%), and silver nitrate (AgNO2, 99.9%). Additional chemicals used were procured from Sigma-Aldrich, Bangalore, India, and included sodium hydroxide (NaOH), methanol, potassium persulfate, ferrous sulfate (FeSO4·7 H2O), ferrozine, acetic acid, sodium acetate, ascorbic acid, ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), 2,4,6-tri-(2-pyridyl)-5-triazine (TPTZ), and iron (III) chloride hexahydrate (FeCl2·6 H2O). Dyes and reagents such as 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH), dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), and 2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) (ABTS) were also sourced from Sigma-Aldrich. All chemicals were used as received without any further purification. Freshly discharged liquid metabolic waste (urine) from a healthy and fully vaccinated Gir cow (Bos taurus indicus, A-2 variety) was used in this study. Urine was donated by the cattle owner, Mr. Dhanaji Parasharam Sarvalkar, located at coordinates 16.7050° N and 74.2433° E.

Synthesis of Ag NPs, rGO, and Ag/rGO nanocomposites

For the synthesis of Ag NPs, the Bos taurus indicus (BTI) urine-mediated method was developed by Sarvalkar et al.20, with a few modifications24. A 0.1 M solution of AgNO2 was prepared in 100 mL double distilled water (DDW). Then, 25 mL of freshly collected BTI urine was added dropwise under constant stirring, resulting in the formation of a brownish solution. Next, 15 mL of a 0.1% (w/v) CTAB solution was added to the mixture as a capping agent. The nanoparticles were collected by centrifugation and each cycle was performed at 5000 rpm for 10 min. The collected material was washed with DDW and ethanol was used to remove excess cationic surfactants. The samples were oven-dried at 60 °C for 12 h, followed by annealing at 200 °C for 1 h. Finally, the material was ground into a fine powder and stored for further characterization and application.

Graphene oxide (GO) was synthesized using the improved Hummers method developed by Marcano et al.26, and reduced graphene oxide (rGO) was prepared through chemical reduction using hydrazine hydrate as the reducing agent27. The detailed synthesis procedures for GO and rGO are provided in the supplementary information. To prepare the Ag/rGO nanocomposite, the BTI-mediated method by Kumbhar et al.24 was followed with slight modifications. Solution A was prepared by dissolving 1.69 g of AgNO2 in 90 mL of DDW. Solution B was prepared by dispersing 0.107 g (10% w/w) rGO in 10 mL DDW using a bath sonicator for 30 min. After sonication, Solution B was mixed with Solution A. Subsequently, 25 mL of BTI urine was added dropwise to the reaction mixture under constant stirring, resulting in the formation of a black-brownish solution. Unlike the method reported by Kumbhar et al.24, CTAB, a capping agent, was excluded from this process. The reaction mixture was centrifuged at 5000 rpm to separate the nanoparticles. The collected material was washed with water and ethanol, oven-dried at 60 °C, and stored for further characterization and application.

Preparation of nanofluid

Methods such as pH adjustment (by adding a dispersant), magnetic stirring, ultrasonication (with notable differences in effectiveness between bath and probe ultrasonication), or combinations of these techniques are commonly used28. Ultrasonication improves the stability, thermophysical properties, and performance of nanofluids and prevents the sedimentation and aggregation of nanomaterials. However, the optimal duration of sonication can vary depending on the specific nanomaterials used29,30,31,32,33. Magnetic stirring is the preferred method for dispersing nanomaterials in low concentrations. Ag NPs are insoluble in water; hence, they are obtained as colloidal dispersions. The nanofluids were prepared in water at various concentrations by simply placing the colloidal solution in a sonicator bath for 30 min to ensure proper dispersion and prevent agglomeration. Aqueous nanofluids of rGO and Ag/rGO nanocomposites at various concentrations were prepared by ultrasonication. The ultrasonic velocities of the nanofluids were determined at concentrations of 0.1, 0.05, 0.025, 0.0125, and 0.00625 mol/dm3 by using a nanofluid interferometer.

Material characterization

The crystalline structures of the Ag NPs and Ag/rGO nanocomposites were characterized using a Bruker D8 Advance X-ray diffractometer (XRD). Raman analysis, in the range of 100–3200 cm−1, was performed using a Renishaw Raman spectroscopy to investigate the molecular structure, defects, and chemical bonding in the Ag NPs and Ag/rGO nanocomposite. The morphology was analyzed by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) using a JEM 2100 Plus (JEOL). The particle size and surface charge were measured using an Anton Paar Litesizer 500 particle size analyzer. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), utilizing the JPS 9030 model from JEOL, was used to analyze the elemental compositions and chemical bonding of the synthesized nanomaterials. The acoustical parameters were measured using a nanofluid ultrasonic interferometer, and the densities of the solutions were measured with a densitometer. The ultrasonic velocity of the as-synthesized nanomaterial dispersion solutions was measured using a nanofluid interferometer [Model NF-10 (2 MHz), Mittal Enterprises, Delhi]. The nanofluid interferometer generated sound waves in the nanofluids at different concentrations. This instrument employs a piezoelectric transducer to generate ultrasound waves at a specified frequency, and the wavelength was measured with high precision using a digital micrometer accurate to within ± 0.001 mm.

Calculations

The experimentally determined values of the ultrasonic velocity and density were used to evaluate the values of the parameters of the acoustic properties using Eqs. (1) and (2)34.

where ρo, ρs, Uo, and Us are the density and ultrasonic velocity of pure solvent and solution, respectively. βs is the adiabatic compressibility35,36 for solution and βo is the adiabatic compressibility for solvent. The intermolecular free length (Lf), specific acoustical impedance (Z), and relative association (RA) were calculated using Eqs. (3)–(5).

where K is the temperature dependent constant known as Jacobson constant37.

The apparent molar volume (φv) can be calculated by the Eq. (6),

where m is the molality of the solute and M is the molecular weight of the solute. The apparent molar compressibility (φk) can be calculated by Eq. (7),

A nanofluid ultrasonic interferometer was used to measure the velocity of ultrasonic waves in liquids. The system employs a high-frequency generator to excite a quartz crystal located at the base of the measuring cell. This cell, featuring double-wall construction, maintained a constant temperature throughout the experiment. Ultrasonic waves were reflected back from a movable plate, creating standing waves between the quartz crystal and reflector plate. Adjustments were made using a micrometer screw to accurately record the maxima and minima of the anode current readings. The distance (d) between successive maxima and minima was measured using a known frequency to determine the ultrasonic velocity. Additionally, the compressibility of the liquid was calculated based on its density.

Antioxidant study of nanomaterials

Ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP) assay

The ability to reduce ferric ions was assessed using the FRAP assay following the methodology described by Benzie and Strain38. FRAP reagent was prepared by mixing 5 mL of 20 mM FeCl3, 50 mL of 0.3 M acetate buffer (pH 3.6), and 5 mL of 10 mM TPTZ in 40 mM hydrochloric acid (HCl), and diluting it to a total volume of 1900 µL for the reaction mixture. A nanomaterial suspension (100 µL) was added to this mixture at various concentrations (20–100 µg/mL). The reaction setup was incubated at 37 °C for 15 min, and the reduction of ferric ions was quantified by measuring absorbance at 593 nm using UV-vis spectroscopy.

Ferrous ion chelating activity (FICA) assay

The iron-chelating activities of Ag NPs and Ag/rGO nanocomposites were evaluated using a modified method proposed by Ebrahimzadeh et al.39. The procedure involved mixing 1850 µL of DDW, 100 µL of 5 mM ferrozine solution, and 1000 µL of nanomaterial suspensions at varying concentrations (20–100 µg/mL) with 50 µL of 2 mM ferrous sulfate solution. The mixed solution was allowed to equilibrate for 10 min at 28 ± 2 °C. After incubation, the absorbance of the solution was measured at 562 nm to assess the formation of the ferrozine-ferrous ion (ferrozine-Fe2+) complexes. The calculation of the inhibition percentage (%) of ferrozine-Fe2+ complex formation is facilitated by Eq. (8).

where As absorbance of the solution, which corresponds to the concentration of the added sample, and Ac is the absorbance of the control solution.

DPPH and ABTS assay

The generation of free radicals during oxidative stress, a phenomenon linked to various pathologies, can be mitigated by antioxidant molecules. The antioxidant potential of Ag NPs and Ag/rGO nanocomposites was evaluated using the DPPH assay, a standard method for assessing free radical scavenging abilities, performed in accordance with the adapted Brand-Williams method40. In the experimental setup, 40 µL of the nanomaterials were mixed with 3 mL of DPPH solution at concentrations ranging from 20 to 100 µg/mL to initiate the antioxidant reaction. The mixture was incubated for 30 min and protected from light to prevent oxidation. The extent of DPPH radical reduction was quantified by measuring the absorbance at 517 nm using UV–vis spectroscopy.

ABTS assay was performed to evaluate the antioxidative capacity of the nanomaterials by measuring their ability to scavenge ABTS radical cations. For the analysis, 200 µL of Ag NPs or Ag/rGO nanocomposite suspension was mixed with 2800 µL of ABTS solution. The ABTS working solution was prepared by incubating a 1:1 mixture of 7 mM ABTS solution and 2.45 mM potassium persulfate solution in the dark for 20 h, allowing the generation of ABTS radical cations. The reagent was diluted to an absorbance of approximately 1 nm at a wavelength of 734 nm. After the reaction mixture was incubated at 30 °C for 10 min, radical scavenging activity (RSA) was quantified by measuring the absorbance. Ascorbic acid was used as a reference standard. Radical scavenging activity (RSA) was determined using Eq. (9).

Results and discussions

Structural characterization of Ag NPs and Ag/rGO nanocomposites

Figure 1 shows the XRD patterns used to analyze the crystalline structures of the Ag NPs and the Ag/rGO nanocomposites. For the Ag NPs and Ag/rGO nanocomposites show similar hkl values of (111), (200), (220), (311), and (222), corresponding to 2θ values of 38.27°, 44.4°, 64.5°, 77.5°, and 81.6°, respectively. The values correspond to the facets of a face-centered cubic (FCC) structure, matching JCPDS card no. 01-089-372220,41. An additional peak at 22.81° in the XRD pattern of the Ag/rGO nanocomposite corresponds to an interplanar spacing of 0.78 nm, associated with the (002) plane of rGO42. The crystallite sizes of the Ag NPs and Ag/rGO nanocomposites are provided in Tables S1 and S2, respectively. Figure 2 shows TEM micrographs of the Ag NPs and Ag/rGO nanocomposite. Figure 2a, b show the TEM micrographs of the Ag NPs, revealing their sizes ranging from 50 to 500 nm with a relatively spherical shape. Figure 2c, d display the TEM micrographs of the rGO nanosheets, which exhibit a flake-like morphology with surface wrinkles. The Ag NPs were distributed across the rGO nanosheets, clearly demonstrating the formation of a nanocomposite structure.

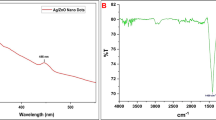

Figure S1 shows the Raman spectroscopy analysis, conducted in the range of 100–3250 cm−1, used to characterize Ag NPs and Ag/rGO nanocomposites. The spectra revealed prominent peaks at 1363 cm−1 (D band) and 1556 cm−1 (G band), corresponding to the symmetric and asymmetric C = O stretching vibrations of the carboxylate group and ν (N = N) aliphatic vibrations, respectively43. Additionally, significant peaks were observed at 237 cm−1, 468 cm−1 attributed to N-C-S vibrational stretching43,44, and 702–706 cm−1 associated with ν C-N-C vibrational stretching45.

Figure S2 a, b illustrate the hydrodynamic diameters of the synthesized nanomaterials. The nano-synthesized Ag NPs (Fig. S2a) exhibit an average hydrodynamic diameter of 258.4 nm with a polydisperse particle distribution, ranging from 118.34 to 395.3 nm. The Ag/rGO nanocomposite (Fig. S2b) had an average hydrodynamic diameter of 833.7 nm, with a size distribution ranging from 200 to 10,000 nm, attributed to the presence of rGO nanosheets46. Notably, the Ag/rGO nanocomposite shows a smaller particle size compared to the previously reported values by Kumbhar et al.24, likely due to the exclusion of CTAB in this synthesis. CTAB may have contributed to the aggregation of rGO sheets, resulting in an increased particle size in an earlier report24. In this study, the BTI-assisted Ag NPs and Ag/rGO nanocomposites exhibited zeta potential values of − 18.4 mV and 33.0 mV, respectively, as shown in Figure S3. The higher zeta potential value of the Ag/rGO nanocomposites indicates enhanced electrostatic stability compared to that of the Ag NPs. The colloidal stability of Ag NPs is primarily attributed to the capping agent and biomolecules present in the BTI urine, which prevent particle agglomeration. In contrast, the enhanced stability of the Ag/rGO nanocomposites is due to the combined effects of biomolecular capping and the structural support provided by the rGO nanosheets. The rGO nanosheets facilitated a more uniform dispersion, thereby improving the overall stability and preventing the precipitation of the nanocomposites in the colloidal suspension47.

Figure 3a–f shows the XPS spectra of the synthesized Ag NPs and Ag/rGO nanocomposites, providing insights into their surface chemical compositions and electronic states. The survey scan, shown in Fig. 3a, indicates the presence of silver as the dominant element, with minimal contamination from other elements. The deconvoluted spectra, depicted in Fig. 3b, display distinct peaks at 374.4 eV and 368.3 eV, corresponding to the Ag 3d3/2 and Ag 3d5/2 core levels, respectively. These peaks confirm the presence of metallic silver (Ag⁰) with high purity25. XPS analysis of the Ag/rGO nanocomposite revealed the successful integration of metallic Ag NPs with rGO nanosheets. The survey scan shown in Fig. 3c confirms the presence of Ag, C, and O, indicating the overall composition. The deconvoluted spectra, as shown in Fig. 3d, exhibit distinct peaks at binding energies of 374.34 eV and 368.23 eV for Ag 3d3/2 and Ag 3d5/2, respectively, confirming the metallic state of silver. The deconvoluted C 1s spectra, illustrated in Fig. 3e, identifies various functional groups with binding energies at 284.5 eV (C–C), 285.48 eV (C-OH), and 288.38 eV (C-O-C and C = O). The O 1s spectrum in Fig. 3f further confirms the presence of oxygen-containing groups, with peaks at the binding energies of 530.57 eV (C = O) and 531.81 eV (C-OH)48,49. These results highlight the specific chemical environment and stability of the nanomaterial, thereby enhancing its potential for various applications.

Measurements and analysis of acoustical parameters

Figure 4a, b shows the measurements of density and ultrasonic velocity for Ag NPs, rGO, and Ag/rGO nanocomposites, highlighting the impact of varying concentrations on the acoustical parameters of these systems. The acoustical parameters of the Ag NPs, rGO, and Ag/rGO nanocomposites were analyzed by measuring the density and ultrasonic velocity at various concentrations (0.1, 0.05, 0.025, 0.0125, and 0.00625 mol/dm3). These results are summarized in Table S3a–c for the densities and ultrasonic velocities, while Tables S4a–c detail the corresponding acoustic parameters. The results demonstrated distinct trends in the ultrasonic velocity, density, and acoustic parameters with varying concentrations. For Ag NPs (Tables S3a, S4a), density decreased linearly with concentration, except for irregular changes observed at 0.05 mol/dm3, where ultrasonic velocity exhibited a rapid increase. The acoustical impedance decreased with concentration, whereas parameters such as apparent molar volume, apparent molar compressibility, intermolecular free length, and relative association showed regular increases, indicating enhanced molecular interactions at lower concentrations. For rGO nanofluids (Table S3b), density irregularly decreased with concentration, except for a rapid decrease at 0.05 mol/dm3, while ultrasonic velocity initially decreased and then increased at lower concentrations. Table S4b shows a decrease in impedance and adiabatic compressibility with decreasing concentration, but the apparent molar compressibility and apparent molar volume displayed irregular increases. The intermolecular free length increased regularly until 0.025 mol/dm3 and then decreased, whereas the relative association decreased slightly at lower concentrations, highlighting complex molecular interactions50. The Ag/rGO nanocomposite nanofluids (Table S4c) exhibited regular decreases in density and irregular decreases in ultrasonic velocity with a smooth increase at lower concentrations. Table S4c indicates a decrease in impedance with decreasing concentration up to 0.025 mol/dm3, followed by a smooth increase. Adiabatic compressibility followed a similar trend, while apparent molar volume and apparent molar compressibility showed continuous increases at lower concentrations. The intermolecular free length exhibited irregular increases, and the relative association increased slightly at lower concentrations, demonstrating enhanced dispersion and interaction stability51.

Figure 5a–f highlights the relationship between density, ultrasonic velocity, and acoustical parameters [adiabatic compressibility (βs), apparent molar volume (φv), and apparent adiabatic compressibility (φK)] across different concentrations. At lower concentrations, decreased density and increased ultrasonic velocity led to enhanced compressibility and molar volume, attributed to better particle dispersion and solute-solvent interactions52. Irregularities at 0.025 mol/dm3 were likely caused by structural changes and unique molecular interactions. Intermolecular free length and relative association decreased irregularly due to closer molecular packing facilitated by higher ultrasonic velocity.

Plot between concentrations verses acoustical parameters (a) Adiabatic compressibility (βs), (b) Apparent molar volume (φv), (c) Apparent molar compressibility (φk), (d) Intermolecular free length (Lf), (e) Relative association (RA), and (f) Specific acoustic impedance (Z) of Ag NPs, rGO and Ag/rGO nanocomposites.

These findings align with the results reported by Ramteke et al.12 and emphasize the role of solute concentration in influencing the acoustical properties. Lower concentrations resulted in enhanced particle-solvent interactions, improving dispersion and stability, while higher concentrations led to aggregation and reduced molecular interaction sites. The behavior of acoustical parameters reflects the balance between particle-particle and particle-solvent interactions53,54, which are critical for applications in catalysis, sensing, and drug delivery55,56. The observed trends underscore the potential of these nanomaterials in advanced acoustic and material science applications. The irregular results at higher concentrations may also stem from the limited solubility of Ag NPs, rGO, and their nanocomposites in water, further affecting their molecular interactions and acoustical properties.

Study of plant growth regulation

This study examined the effects of Ag NPs and Ag/rGO nanocomposites on Spinacia oleracea L. (spinach) and Trigonella foenum-graecum L. (fenugreek) plants, focusing on plant growth regulators (PGRs). Parameters such as germination percentage, survival rate, shoot length, root length, and seedling height were analyzed. The results are detailed in Tables 1 and 2 for spinach and fenugreek, respectively. The study employed solutions of 0.01, 0.005, and 0.0025 mol/dm3, prepared by soaking 10 healthy seeds of each plant for 8 h. After soaking, the seeds were transferred to Petri dishes for germination and observed for 5 days. Germinated seeds were transplanted into fertile soil after 10 days, and the PGR parameters were measured.

The general order of plant growth regulation was found to be:

-

(a)

For Spinach oleracea L- control > Ag/rGO nanocomposite > Ag NPs.

-

(b)

For Trigonella foenum graecum L.- Ag/rGO nanocomposite > Ag NPs > control.

The data show that the Ag NPs and Ag/rGO nanocomposites function effectively as plant growth regulators. The average values for parameters such as germination percentage, survival rate, seedling height, and shoot length were highest in the nanocomposite treatment, followed by Ag NPs, and lowest in the control group. The effectiveness of the Ag/rGO nanocomposite treatment was particularly significant for seed germination in fenugreek and spinach, demonstrating its potential as an advanced method for promoting growth in beneficial crop plants. Ag NPs influence plant growth and development through their interactions with PGRs. The germination rates of spinach and fenugreek seeds exhibited a concentration-dependent response, as shown in Figs. S4a and S5a. At lower concentrations (0.005 and 0.0025 mol/dm3), germination rates increased to 100% for spinach and 40% for fenugreek, likely because of the antimicrobial properties of Ag NPs, which reduced microbial load and enhanced seed viability. However, at higher concentrations (0.01 mol/dm3), germination rates declined, possibly due to the phytotoxic effects of Ag NPs at elevated levels.

Growth parameters, such as root and shoot length, followed a similar trend. At low to moderate concentrations (0.0025–0.005 mol/dm3), root and shoot elongation was promoted in both spinach and fenugreek, as shown in Figs. S4b and S5b. This effect may be attributed to the modulation of auxin and gibberellin levels by Ag NPs, enhancing cell division and elongation. At higher concentrations, root and shoot lengths were adversely affected, likely due to hormonal imbalance and disrupted cellular metabolism57. The Ag/rGO nanocomposite exhibited synergistic effects, combining the antimicrobial properties of Ag NPs and nutrient uptake facilitation by rGO. At low to moderate concentrations (0.0025–0.005 mol/dm3), germination rates were 100% for spinach and 40% for fenugreek, with enhanced seedling development. However, at higher concentrations, germination rates decreased for spinach, but increased to an average of 70% for fenugreek, likely due to species-specific responses. The nanocomposite positively influenced root and shoot growth at lower concentrations, whereas higher concentrations caused reduced growth, likely due to the combined phytotoxic effects of both nanomaterials57,58.

Notably, the synthesis of Ag/rGO nanocomposites did not involve CTAB, a capping agent commonly used for Ag NPs. CTAB, a hazardous chemical, may contribute to the aggregation of rGO sheets and potentially affect plant growth. The absence of CTAB in the Ag/rGO nanocomposite synthesis likely enhanced its biocompatibility and effectiveness compared with the Ag NPs synthesized with CTAB. The improved dispersion and reduced toxicity of the nanocomposite, combined with its synergistic properties, underscore its potential as a safer and more effective plant growth regulator. The Ag/rGO nanocomposites demonstrated enhanced performance at lower concentrations (0.0025–0.005 mol/dm3) and enhanced germination, seedling growth, and plant development. At higher concentrations, the effects were mixed, resembling those of Ag NPs. These findings highlight the potential of Ag/rGO nanocomposites as advanced plant growth regulators for agricultural applications59.

Antioxidant study

The study demonstrated a positive correlation between sample concentration and antioxidant capacity, as evidenced by the FRAP activity of the as-synthesized nanomaterials60. As shown in Fig. 6a, the absorbance values increased with increasing concentrations, confirming a dose-dependent enhancement in antioxidant activity. Spectrophotometric measurements at 593 nm revealed a linear increase in the FRAP activity across the tested concentration range (20–100 µg/mL). Ascorbic acid displayed the highest antioxidant potential, with the absorbance values escalating from 0.59 to 2.10. Similarly, Ag NPs and Ag/rGO nanocomposites exhibited increases from 0.46 to 0.85 and 0.51 to 1.12, respectively. This consistent increase suggests that higher concentrations of these nanomaterials provide more reducing agents, facilitating the conversion of Fe3+⁺ ions to Fe2+ ions. These findings highlight the dose-dependent antioxidative properties of the samples, with a linear relationship between concentration and FRAP activity61,62.

Nanomaterials are highly valued for their ability to chelate ferric (Fe3+) and ferrous (Fe2+) ions, making them crucial for applications such as water treatment, protection against metal toxicity, and medical interventions63. The FICA assay measures the capacity of compounds to bind ferrous ions, thereby evaluating their antioxidative efficacy by preventing the formation of harmful hydroxyl radicals through ferrous ion complexation64,65. Figure 6b illustrates the chelating activity of various substances across a concentration range of 20–100 µg/mL, revealing a progressive increase in the chelation efficiency. EDTA, used as a control, demonstrated the highest ferrous ion chelating efficiency, reaching 93.42% at 100 µg/mL. The Ag NPs and Ag/rGO nanocomposites also exhibited notable chelating activities, with values of 54.3% and 73.4%, respectively, at the same concentration. These results highlight the dose-dependent chelating activity of nanomaterials and their significant antioxidative potential, highlighting their importance in combating oxidative stress and mitigating metal-induced toxicity.

Figure 6c, d presents a comparative analysis of the antioxidant efficacy of the synthesized nanomaterials relative to ascorbic acid, a standard antioxidant. Antioxidants play a vital role in biological systems by neutralizing free radicals, which can compromise the cellular integrity and functionality66. DPPH and ABTS assays are widely used to measure the antioxidant activity. The DPPH assay involves the formation of a violet DPPH− radical, whereas the ABTS assay evaluates activity in both lipophilic and hydrophilic environments by generating a green/blue ABTS+ radical cation66. Both methods rely on the single-electron transfer-proton transfer (SPLET) mechanism in aqueous solutions, emphasizing the interaction between radicals and antioxidants and the partial ionization of phenols67. Notably, the reaction kinetics of these assays vary, affecting the observed rates of antioxidant reactivity66,68. The antioxidative properties of the Ag NPs and Ag/rGO nanocomposites were assessed using these assays. At a concentration of 100 µg/mL, the DPPH scavenging activity was 89.95% for ascorbic acid, 39.67% for Ag NPs, and 65.69% for Ag/rGO nanocomposites. Similarly, the ABTS scavenging activities were 94.21%, 56.52%, and 65.01% for ascorbic acid, Ag NPs, and Ag/rGO nanocomposites, respectively. The significant decolorization of the DPPH assay’s characteristic dark violet color, along with reduced absorbance, highlighted the effective free radical scavenging capabilities of the tested substances. This reduction in absorbance intensity underscores the proficiency of these materials as electron donors, efficiently neutralizing electron-deficient species and establishing their role as potent antioxidants22,24.

Conclusions

This study provides a comprehensive analysis of the acoustical, antioxidant, and plant growth regulatory properties of Ag NPs, rGO, and their nanocomposites synthesized through a surfactant-free approach using Bos taurus indicus metabolic waste. Notably, surfactant-free synthesis also reduced the particle size of Ag/rGO nanocomposites, enhancing their dispersion, stability, and reactivity. A linear relationship between the concentration and density in the nanofluids was observed, while the ultrasonic velocity exhibited irregular changes. Key acoustical parameters, including adiabatic compressibility, apparent molar compressibility, and apparent molar volume, consistently increased with decreasing concentration. Conversely, parameters such as the intermolecular free length, relative association, and acoustic impedance showed irregular decreases. The irregular behavior observed at 0.025 mol/dm3 suggests unique structural or interaction changes, likely driven by complex nanoparticle-solvent interactions. The enhanced acoustical properties of the Ag/rGO nanocomposites indicate their potential applications in advanced acoustic technologies, including sound absorption, ultrasonic imaging, and communication systems.

Antioxidant studies revealed significant free radical scavenging abilities for both Ag NPs and Ag/rGO nanocomposites, as demonstrated by the FRAP, FICA, DPPH, and ABTS assays. The superior antioxidant activity of Ag/rGO nanocomposites compared to Ag NPs underscores their potential to mitigate oxidative stress-induced biological damage and contribute to the development of therapeutic agents for chronic diseases. Additionally, the application of Ag NPs and Ag/rGO nanocomposites as plant growth regulators at low concentrations introduces a novel approach to enhance crop yield and optimize agricultural practices. The multifunctional nature, reduced particle size, and superior antioxidant properties of these nanocomposites highlight their potential for diverse applications across the biomedical, agricultural, and environmental domains. Future research should focus on evaluating the long-term stability, environmental impact, and biocompatibility of these nanocomposites for various applications. Furthermore, exploring combinations with other nanomaterials to enhance their multifunctional properties can pave the way for advancements in sustainable and innovative nanotechnology.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Babar, H. & Ali, H. M. Towards hybrid nanofluids: Preparation, thermophysical properties, applications, and challenges. J. Mol. Liq. 281, 598–633 (2019).

Wan, M., Yadav, R. R., Yadav, K. L. & Yadav, S. B. Synthesis and experimental investigation on thermal conductivity of nanofluids containing functionalized Polyaniline nanofibers. Exp. Therm. Fluid Sci. 41, 158–164 (2012).

Bahiraei, M. & Heshmatian, S. Electronics cooling with nano fluids: a critical review. Energy Convers. Manag. 172, 438–456 (2018).

Raihan, A., Ali, I. & Salam, B. A review on nanofluid: Preparation, stability, thermophysical properties, heat transfer characteristics and application. SN Appl. Sci. 2, 1–17 (2020).

Kuram, E., Bagherzadeh, A. & Budak, E. Application of cutting fluids in micro-milling—A review. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 133, 1 (2024).

Ahmed, F. & Khan, W. A. Efficiency enhancement of an air-conditioner utilizing nanofluids: an experimental study. Energy Rep. 7, 575–583 (2021).

Tao, Q., Zhong, F., Deng, Y., Wang, Y. & Su, C. A review of nanofluids as coolants for thermal management systems in fuel cell vehicles. Nanomaterials 13, 1 (2023).

Yang, C. H. et al. Microfluidic assisted synthesis of silver nanoparticle–chitosan composite microparticles for antibacterial applications. Int. J. Pharm. 510, 493–500 (2016).

Yu, W. & Xie, H. A review on nanofluids: Preparation, stability mechanisms, and applications. J. Nanomater. 2012, 1 (2012).

Rashin, M. N. & Hemalatha, J. Acoustical studies of the intermolecular interaction in copper oxide-ethylene glycol nanofluid. Adv. Nanomater. Nanotechnol. 143, 225–229 (2013).

Das, N., Kumar Praharaj, M. & Panda, S. Exploring ultrasonic wave transmission in liquids and liquid mixtures: a comprehensive overview. J. Mol. Liq. 403, 124841 (2024).

Ramteke, A. A. et al. Study of acoustical properties of lead oxide nanoparticle in different solvent mixtures at 305 K by using nanofluid interferometer. Macromol. Symp. 400, 1–6 (2021).

Agostino, F. J. & Krylov, S. N. advances in steady-state continuous-flow purification by small-scale free-flow electrophoresis. Trends Anal. Chem. 72, 68–79 (2015).

Mahbubul, I. M., Elcioglu, E. B., Saidur, R. & Amalina, M. A. Optimization of ultrasonication period for better dispersion and stability of TiO2–water nanofluid. Ultrason. Sonochem. 37, 360–367 (2017).

Thirumaran, S., Mathammal, R. & Thenmozhi, P. Acoustical and thermodynamical properties of ternary liquid mixtures at 303.15 K. Chem. Sci. Trans. 1, 674–682 (2012).

Taneja, L. & Dahiya, N. Ultrasonic study of silver nanoparticles for various applications. Integr. Ferroelectr. 184, 101–107 (2017).

Kumar, M., Sawhney, N., Sharma, A. K. & Sharma, M. Acoustical and thermodynamical parameters of aluminium oxide nanoparticles dispersed in aqueous ethylene glycol. Phys. Chem. Liq. 55, 463–472 (2017).

Sarvalkar, P. D. et al. A review on multifunctional nanotechnological aspects in modern textile. J. Text. Inst. 1, 1–18 (2022).

Pawar, C. A. et al. A comparative study on anti-microbial efficacies of biologically synthesized nano gold using Bos taurus indicus urine with pharmaceutical drug sample. Curr. Res. Green. Sustain. Chem. 5, 100311 (2022).

Sarvalkar, P. D. et al. Bio-mimetic synthesis of catalytically active nano-silver using Bos taurus (A-2) urine. Sci. Rep. 11, 16934 (2021).

Prasad, S. R. et al. Bio-inspired synthesis of catalytically and biologically active palladium nanoparticles using Bos taurus urine. SN Appl. Sci. 2, 754 (2020).

Karvekar, O. S. et al. Bos taurus (A–2) urine assisted bioactive cobalt oxide anchored ZnO: a novel nanoscale approach. Sci. Rep. 12, 15584 (2022).

Padvi, M. N. et al. Bos taurus urine assisted biosynthesis of CuO nanomaterials: A new paradigm of antimicrobial and antineoplatic therapy. Macromol. Symp. 392, 1900172 (2020).

Kumbhar, G. S. et al. Synthesis of a Ag/rGO nanocomposite using Bos taurus indicus urine for nitroarene reduction and biological activity. RSC Adv. 12, 35598–35612 (2022).

Sarvalkar, P. D. et al. Bio-inspired synthesis of biologically and catalytically active silver chloride-anchored Palladium/Gold/Silver trimetallic nanoparticles. Catal. Commun. 1, 106897. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catcom.2024.106897 (2024).

Marcano, D. C. et al. Improved synthesis of graphene oxide. ACS Nano 4, 4806–4814 (2010).

Adarsh Rag, S., Selvakumar, M., Bhat, S., Chidangil, S. & De, S. Synthesis and characterization of reduced graphene oxide for supercapacitor application with a biodegradable electrolyte. J. Electron. Mater. 49, 985–994 (2020).

Ali, H. M. et al. Preparation techniques of TiO2 nanofluids and challenges: a review. Appl. Sci. 8, 1 (2018).

Adio, S. A., Sharifpur, M. & Meyer, J. P. Influence of ultrasonication energy on the dispersion consistency of Al2O3–glycerol nanofluid based on viscosity data, and model development for the required ultrasonication energy density. J. Exp. Nanosci. 11, 630–649 (2016).

Afzal, A., Nawfal, I., Mahbubul, I. M. & Kumbar, S. S. An overview on the effect of ultrasonication duration on different properties of nanofluids. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 135, 393–418 (2019).

Asadi, A. & Alarifi, I. M. Effects of ultrasonication time on stability, dynamic viscosity, and pumping power management of MWCNT-water nanofluid: an experimental study. Sci. Rep. 10, 1–10 (2020).

Mahbubul, I. M., Saidur, R., Amalina, M. A., Elcioglu, E. B. & Okutucu-Ozyurt, T. Effective ultrasonication process for better colloidal dispersion of nanofluid. Ultrason. Sonochem. 26, 361–369 (2015).

Sandhya, M., Ramasamy, D., Sudhakar, K., Kadirgama, K. & Harun, W. S. Ultrasonication an intensifying tool for preparation of stable nanofluids and study the time influence on distinct properties of graphene nanofluids—A systematic overview. Ultrason. Sonochem. 73, 105479 (2021).

Ramteke, A., Narwade, M. L. & Mahavidhyalaya, V. Studies in acoustical properties of chloro subsitituted pyrazoles in different concentration and different percentages in dioxane–water mixture. 4, 254–261 (2012).

Balakrishnan, J., Balasubramanian, V., Rajesh, S. & Sivakumar, M. Acoustic study of atropine sulphate in water of various concentrations at 35°C using ultrasonic interferometer. J. Chem. Pharm. Res. 4, 4283–4288 (2012).

Chanamai, R. & Julian McClements, D. Ultrasonic attenuation of edible oils. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 75, 1447–1448 (1998).

Crombie, L. Amides of vegetable origin. Part V. Stereochemistry of conjugated dienes. J. Chem. Soc. 1, 1 (1953).

Benzie, I. F. F. & Strain, J. J. The ferric reducing ability of plasma (FRAP) as a measure of ‘antioxidant power’: the FRAP assay. Anal. Biochem. 239, 70–76 (1996).

Ebrahimzadeh, M. A., Pourmorad, F. & Bekhradnia, A. R. Iron chelating activity, phenol and flavonoid content of some medicinal plants from Iran. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 7, 3188–3192 (2008).

Brand-Williams, W., Cuvelier, M. E. & Berset, C. Use of a free radical method to evaluate antioxidant activity. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 28, 25–30 (1995).

Belachew, N., Meshesha, D. S. & Basavaiah, K. Green syntheses of silver nanoparticle decorated reduced graphene oxide using l-methionine as a reducing and stabilizing agent for enhanced catalytic hydrogenation of 4-nitrophenol and antibacterial activity. RSC Adv. 9, 39264–39271 (2019).

Sarvalkar, P. D. et al. Synthesized rGO / f-MWCNT-architectured 1-D ZnO nanocomposites for azo dyes adsorption, photocatalytic degradation, and biological applications. Catal. Commun. 187, 106846 (2024).

Hsu, K. C. & Chen, D. H. Microwave-assisted green synthesis of Ag/reduced graphene oxide nanocomposite as a surface-enhanced Raman scattering substrate with high uniformity. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 9, 1–9 (2014).

Xiong, R., Hu, K., Zhang, S., Lu, C. & Tsukruk, V. V. Ultrastrong freestanding graphene oxide nanomembranes with surface-enhanced Raman scattering functionality by solvent-assisted single-component layer-by-layer assembly. ACS Nano 10, 6702–6715 (2016).

Vuong, L. D., Luan, N. D. T., Ngoc, D. D. H., Anh, P. T. & Bao, V. V. Q. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles from fresh leaf extract of Centella asiatica and their applications. Int. J. Nanosci. 16, 1–8 (2017).

Noor, N. et al. Durable antimicrobial behaviour from silver-graphene coated medical textile composites. Polymer (Basel) 11, 1–21 (2019).

Ahamed, M., Akhtar, M. J., Majeed Khan, M. A. & Alhadlaq, H. A. A novel green preparation of ag/rgo nanocomposites with highly effective anticancer performance. Polymer (Basel) 13, 1–14 (2021).

Tawade, A. K. et al. Enhanced supercapacitor performance through synergistic electrode design: reduced graphene oxide-polythiophene (rGO-PTs) nanocomposite. Chem. Eng. J. 492, 151843 (2024).

Wang, R., Wang, Y., Xu, C., Sun, J. & Gao, L. Facile one-step hydrazine-assisted solvothermal synthesis of nitrogen-doped reduced graphene oxide: reduction effect and mechanisms. RSC Adv. 3, 1194–1200 (2013).

Nithya, G., Thanuja, B. & Kanagam, C. C. Study of intermolecular interactions in binary mixtures of 2′-chloro-4-methoxy-3-nitro benzil in various solvents and at different concentrations by the measurement of acoustic properties. Ultrason. Sonochem. 20, 265–270 (2013).

Park, J. O. et al. Aggregation of Ag nanoparticle based on surface acoustic wave for surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy detection of dopamine. Anal. Chim. Acta 1285, 342036 (2024).

Reichel, H. et al. Nucleation and growth of plasma sputtered silver nanoparticles under acoustic wave activation. Appl. Surf. Sci. 669, 1 (2024).

Wu, H. et al. Efficient molecular approach to quantifying solvent-mediated interactions. Langmuir 33, 11817–11824 (2017).

Batista, C. A. S. & Larson, R. G. Kotov, N. A. Nonadditivity of nanoparticle interactions. Science 350, 1 (2015).

Minelli, G., Puglisi, G. E. & Astolfi, A. Acoustical parameters for learning in classroom: a review. Build. Environ. 208, 108582 (2022).

Pourmehran, O., Cazzolato, B., Tian, Z. & Arjomandi, M. Acoustically-driven drug delivery to maxillary sinuses: Aero-acoustic analysis. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 151, 105398 (2020).

Wang, L. et al. Silver nanoparticles regulate Arabidopsis root growth by concentration-dependent modification of reactive oxygen species accumulation and cell division. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 190, 110072 (2020).

Hatami, M., Hosseini, S. M., Ghorbanpour, M. & Kariman, K. Physiological and antioxidative responses to GO/PANI nanocomposite in intact and demucilaged seeds and young seedlings of Salvia mirzayanii. Chemosphere 233, 920–935 (2019).

Soni, S., Jha, A. B., Dubey, R. S. & Sharma, P. Nanowonders in agriculture: unveiling the potential of nanoparticles to boost crop resilience to salinity stress. Sci. Total Environ. 925, 171433 (2024).

Payne, A. C., Mazzer, A., Clarkson, G. J. J. & Taylor, G. Antioxidant assays—consistent findings from FRAP and ORAC reveal a negative impact of organic cultivation on antioxidant potential in spinach but not watercress or rocket leaves. Food Sci. Nutr. 1, 439–444 (2013).

Amarowicz, R. & Pegg, R. B. Natural antioxidants of plant origin. Adv. Food Nutr. Res. 90, 1–81 (2019).

Bitencourt, P. E. R. INC, Nanoparticle Formulation of Syzygium cumini, Antioxidants, and Diabetes: Biological Activities of S. cumini Nanoparticles. Diabetes: Oxidative Stress and Dietary Antioxidants. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-815776-3.00035-8 (2020).

Sarvalkar, P. D. et al. Biogenic synthesis of Co3O4 nanoparticles from Aloe barbadensis extract: antioxidant and antimicrobial activities, and photocatalytic degradation of azo dyes. Results Eng. 22, 102094 (2024).

Bonvin, D., Bastiaansen, J. A. M., Stuber, M., Hofmann, H. & Ebersold, M. M. Chelating agents as coating molecules for iron oxide nanoparticles. RSC Adv. 7, 55598–55609 (2017).

Sathishkumar, K. et al. Free radicals and antioxidant protocols. Free Radic. Antioxid. Protoc. 610, 51–61 (2010).

Ilyasov, I. R., Beloborodov, V. L., Selivanova, I. A. & Terekhov, R. P. ABTS/PP decolorization assay of antioxidant capacity reaction pathways. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21 (2020).

Wang, Y. et al. Enrichment, analysis, identification and mechanism of antioxidant components in Toona Sinensis. Chin. J. Anal. Chem. 51, 100198 (2023).

Platzer, M. et al. Common trends and differences in antioxidant activity analysis of phenolic substances using single electron transfer based assays. Molecules 26 (2021).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the support of Department of Chemistry and Science Instrumentation Facility Centre (funded by DST-FIST, New Delhi), Devchand College Arjunnagar, Dist. Kolhapur (M.S.) India for provides the instrument to carry out the measurement of acoustical properties and germination study. We are also thankful to School of Nanoscience and Biotechnology, Shivaji University Kolhapur, (M.S.) India for providing necessary laboratory facilities to synthesis the materials and utilize the facilities for characterizations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: AAR. Performed the experiments: AAR, PDS and ASJ. Data analysis: AAR, PDS, NRP and ARY. The original manuscript was written by: AAR and PDS. Examined and amended the manuscript: AAR, NRP and KKS.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sarvalkar, P.D., Jagtap, A.S., Prasad, N.R. et al. Bio-inspired preparation of Ag NPs, rGO, and Ag/rGO nanocomposites for acoustical, antioxidant, and plant growth regulatory studies. Sci Rep 15, 3281 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87705-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87705-1