Abstract

Pocket hematoma is a common and serious complication following cardiac implantable electronic device (CIED) implantation, contributing to significant morbidity and mortality. This study aimed to evaluate the efficacy of a novel pocket compression device in reducing pocket hematoma occurrence. We enrolled 242 patients undergoing CIED implantation, randomly assigning them to receive either the novel compression vest with a pressure cuff or conventional sandbag compression. Pocket hematomas were categorized as grade 1 (mild), grade 2 (moderate), or grade 3 (severe, requiring intervention or prolonged hospitalization). The primary endpoint, incidence of pocket hematoma 24 h post-procedure, did not significantly differ between the two groups (26.7% vs. 19.7%, p = 0.224). Rates of grade 2 hematoma were similarly low and comparable (2.5% vs. 0.8%, p = 0.368), with no grade 3 hematomas observed. Skin reactions and patient comfort were similar between groups. The sole predictor for hematoma occurrence was current oral anticoagulation use. In conclusion, our study found a low incidence of clinically significant pocket hematomas. The novel pocket compression device showed comparable efficacy to conventional methods, suggesting it as a viable alternative for reducing post-procedural complications without additional adverse effects.

Trial registration number: The study was registered in the Thai Clinical Trials Registry (TCTR) at https://www.thaiclinicaltrials.org/ , with the identification number TCTR20230913005, date of first trial registration 13/09/2023.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Over recent years, cardiac implantable electronic devices (CIEDs) consisting of permanent pacemakers (PPMs), implantable cardioverter defibrillators (ICDs), and cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) have become the standard care for various cardiac conditions, including bradyarrhythmia, prevention of sudden cardiac death, and treatment in patients with severe heart failure1,2.

Pocket hematoma is one of the most common postoperative complications after CIED implantation, with reported incidences ranging between 4 and 28.7%3,4,5,6. Device infection stands out as a particularly severe outcome of pocket hematoma. Previous studies have demonstrated an association between pocket hematoma and a higher rate of device-related infection, including pocket infection, endocarditis, and bloodstream infection7. Additionally, pocket hematoma has been linked to prolonged hospitalization, increased costs, and higher in-hospital mortality8.

To prevent pocket hematoma and its consequences, various pre-operative, intra-operative, and post-operative strategies have been employed to reduce the incidence. A previous study reported that maintaining uninterrupted warfarin before the operation significantly decreased the incidence of pocket hematoma compared to interrupting warfarin with heparin bridging9. Other intraoperative recommendations include meticulous cautery use, packing with antibiotic-soaked sponges, pocket irrigation, and the use of monofilament sutures10.

Pressure dressings have been utilized to apply compression over the surgical site to prevent hematoma. Recent studies indicate that pocket compression devices offer more consistent pressure on the surgical site compared to the conventional method using sandbag compression11. Furthermore, the use of pocket compression device has been associated with significantly lower rates of pocket hematoma3,4,5,12. Therefore, we have developed a pocket compression device using a one-shoulder vest with a pressure cuff to apply constant pressure to the surgical site. We aimed to assess the preventive effects of this pocket compression device on the incidence of pocket hematoma after CIED implantation compared to the conventional method.

Methods

Study design and population

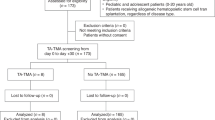

This prospective randomized open blinded endpoint (PROBE) study was conducted at Maharaj Nakorn Chiang Mai Hospital and Chiang Rai Prachanukroh Hospital. All patients aged over 18 years admitted for CIED implantation, including PPM, ICD, CRT, or pulse generator (PG) change, were eligible for the study. Exclusions comprised patients unwilling to cooperate while wearing a device, unable to wear a device, or incapable of attending follow-up appointments at 4-week intervals. The study protocol received approval from the ethics committee of the Faculty of Medicine, Chiang Mai University, approval number 427/2565, date of ethics approval 2/12/2022. The investigations were carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, including written informed consent of all participants. The study was registered in the Thai Clinical Trials Registry (TCTR) at https://www.thaiclinicaltrials.org/, with the identification number TCTR20230913005, date of first trial registration 13/09/2023.

The reported incidence of pocket hematoma in the pocket compression device group and the standard group was 13% and 31%, according to prior study by Fei and colleagues5. To achieve 80% power with an alpha of 0.05, we estimated that 82 patients per group were required.

Treatment protocol

All procedures were conducted by experienced electrophysiologists (EP) or EP fellows under staff supervision. Anticoagulation and antiplatelet therapy were maintained without interruption, and prophylactic antibiotics (first-generation cephalosporin or clindamycin for patients with penicillin allergy) were administered before the procedure. Intraoperatively, electrocautery was used, and absorbable sutures were employed for skin closure. Postoperative standard care involved applying pressure dressing with gauze and transparent waterproof wide-area adhesive tape.

Patients were randomly assigned to one of two treatment groups using a computer-generated, randomized arrangement. Randomization was pre-specified based on the current use of oral anticoagulants (OAC) or dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT). The control group received a 1-kg sandbag over the surgical area for 2 hours to maintain adequate pressure, while the experimental group utilized a pocket compression device. (Fig. 1) The device was crafted as a one-shoulder vest made from fabric and Velcro tape, featuring a pump wedge measuring 15 × 16 cm and a pressure cuff. To achieve optimal compressive pressure at 30 mmHg, equivalent to conventional 1-kilogram sandbag pressure dressing, the pressure cuff was manually inflated 12 times. Patients in the experimental group wore pocket compression vests for 16 to 24 h. (Fig. 2).

Study outcome

The primary outcome was the presence of pocket hematoma following CIED implantation at 24 hours post-operation. An assessor, blinded to the intervention, examined the pocket on the day after the operation and again at the 4-week follow-up. The pocket compression device was removed at the medical ward before assessing for pocket hematoma at the cardiac pacing clinic. The severity of pocket hematoma was classified on a 3-grade scale. Grade 1 pocket hematoma was defined as ecchymosis or mild effusion in the pocket without swelling or pain to the device-pocket. Grade 2 pocket hematoma was characterized by a moderate effusion in the pocket leading to swelling, causing functional impairment or pain to the device-pocket, or any palpable mass protruding ≥ 2 cm but < 4 cm. Grade 3 pocket hematoma was defined as any hematoma protruding more than 4 cm or requiring reoperation and/or resulting in the prolongation of hospitalization and/or necessitating the interruption of OAC13,14.

The secondary outcomes included the incidence of pocket hematoma at the 4-week follow-up period, adverse skin reactions, the patient-comfort scale, and the identification of independent predictors of pocket hematoma. A Visual Analog Scale (VAS) was utilized to assess patient comfort during the compression application period15. The VAS featured a 100-mm-long horizontal line, with the left end marked ‘0’ for ‘very uncomfortable’ and the right end marked ‘10’ for ‘very comfortable’16. The VAS for patient comfort was measured at 24 hours following device application.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were conducted on an intention-to-treat basis. Demographic variables were compared between groups using a t-test for normally distributed values, and the Mann–Whitney U test was employed for non-normally distributed values. Proportions were compared using the Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. Continuous variables were presented as mean ± SD or median ± interquartile range (IQR) when appropriate, while categorical variables were reported as percentages. In multivariate analysis, adjustments were made for potential covariates, including age, sex, body mass index (BMI), co-morbidities, type of CIED, type of antithrombotic agents, type of pocket, procedure duration, and the use of the pocket compression device, in assessing the occurrence of pocket hematoma. Variables with a p-value < 0.10 in univariate analysis were included in the multivariate model. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The statistical software package SPSS version 27 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA, https://www.ibm.com/products/spss-statistics) was used for statistical analysis.

Results

All 262 consecutive patients who underwent CIED implantation between January and November 2023 were enrolled in our study. Sixteen patients were excluded, and data on the primary outcome was lacking for four patients. Consequently, the analysis included the remaining 242 patients.

The median duration of pocket compression device application was 15 (IQR 13, 17) hours, while all patients in the control group received sandbag compression for 2 hours. The baseline demographic data were comparable between the groups. The presence of concurrent use of antithrombotic agents was also similar between the experimental and standard groups, consisting of warfarin (23.3% vs. 20.5%, p = 0.643), direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) (7.5% vs. 9.0%, p = 0.816), DAPT (9% vs. 9%, p = 1.000), single aspirin therapy (24.2% vs. 25.4%, p = 0.882), and single clopidogrel therapy (9.2% vs. 7.4%, p = 0.648). There were no statistically significant differences in coagulation laboratory profiles, including platelet count and International Normalized Ratio (INR) levels. The CIEDs were placed in prepectoral pocket in majority of the patients. Additional data are shown in Table 1.

At the 24-hour postoperative evaluation, there was no statistically significant difference observed in the incidence of pocket hematoma, the primary outcome, between the groups (26.7% vs. 19.7%, p = 0.224). The grading of pocket hematoma predominantly falls within grade 1. We observed only 4 patients with grade 2 pocket hematoma, and there were no incidences of grade 3 pocket hematoma (Table 2). At the 4-week follow-up interval, a minor incidence of hematoma was observed. Regarding safety outcomes, there were no major adverse skin reactions, and the patient comfort score was comparable between both groups.

In patients with concurrent use of OAC or DAPT, hematoma occurred more frequently compared to those using only single antiplatelet therapy or no concurrent use of antithrombotic medications (34.8% vs. 16.0%, p < 0.001) (Fig. 3). The univariate analysis aiming at identifying the predictive factors for pocket hematoma showed that the use of OAC was associated with the increased risk of pocket hematoma (OR 2.800, 95% CI 1.518–5.164, p < 0.001). There is a trend for chronic kidney disease (CKD) to be associated with a higher risk of pocket hematoma (OR 2.00, 95% CI 0.99–4.01, p = 0.051), however, this did not reach statistical significance. Notably, the use of DAPT was not associated with increased risk of pocket hematoma. (OR 1.895, 95% CI 0.614–5.848, p = 0.266).

After multivariate analysis adjusting with variables with a p-value < 0.10, including the use of OAC and CKD, the utilization of OAC emerged as the sole independent factor associated with the occurrence of pocket hematoma (adjusted OR 2.75, 95% CI 1.44–5.26, p = 0.002). Additional adjustments were made for potential covariates, including age, sex, BMI, comorbidities, type of CIED, type of antithrombotic agents, type of pocket, procedural duration, and the use of a pocket compression device. Following these adjustments, the use of OAC remained an independent predictor of pocket hematoma occurrence (adjusted OR 2.73, 95% CI 1.40–5.32, p = 0.03).

Discussion

This prospective randomized study aimed to evaluate the efficacy of a newly designed pocket compression device in reducing the incidence of pocket hematoma following CIED implantation compared to the conventional pressure dressing method using a 1-kg sandbag. In contrast to previous clinical studies3,4,5,12, our findings indicate that there was no statistically significant difference in the rate of hematoma occurrence between the compression device group and the control group.

A previous study by Kiuchi and colleagues evaluated the effectiveness of a pocket compression device resembling the design of our own compression device11. They used a portable interface pressure sensor to precisely measure the pressure between the body and contact surfaces. In contrast, our design uses a more widely available pump wedge to apply pressure over the pocket area without employing a pressure sensor. The absence of pressure monitoring capabilities leaves room for potential fluctuations in the pressure of the pump wedge over time. This could lead to inadequate pressure application, thereby potentially limiting the efficacy of the device due to technical inaccuracies. Furthermore, in our study, patients who used the sandbag compression for 2 hours reported similar comfort levels to those who used the pocket compression device for 16–24 hours. This suggests that the pocket compression device may have minimal impact on discomfort, regardless of the total duration of use.

Importantly, in our study of 242 patients, we observed a very low incidence of grade 2 hematoma (1.6%), and no patients developed grade 3 hematoma. Prior studies have reported the rates of grade 2 and grade 3 hematoma ranging from 4 to 6% to 1–7% respectively4,5,6. One possible explanation is that the very low incidence of significant hematoma in our study may have been influenced by the Hawthorne effect. The key insight of the Hawthorne effect is that individuals alter their behavior when they perceive they are under observation17. The Hawthorne effect may be more prominent in our study due to closer patient monitoring, frequent interactions with the healthcare team, and heightened adherence to care protocols. These conditions likely fostered greater awareness and compliance among patients and providers, reducing complications like grade 2 and 3 hematomas. In contrast, other studies may have differed in monitoring intensity, patient-provider interactions, or emphasis on protocol adherence, leading to a less pronounced Hawthorne effect. Our findings underscore the importance of meticulous care to prevent intraoperative bleeding during CIED implantation, regardless of pocket compression measures.

Previous retrospective studies demonstrated a correlation between the continuation of DAPT and OAC during surgery and the occurrence of postoperative pocket hematoma18,19. Tompkins and colleagues conducted a review of bleeding complications in 1388 patients undergoing ICD or PPM implantation. Their findings revealed that the combination of aspirin and clopidogrel significantly elevated the risk of bleeding compared to individuals not on antiplatelet therapy. Our findings align with previous research, suggesting that patients continuing OAC, whether with warfarin or DOACs, have an increased incidence of pocket hematoma compared to those without antithrombotic therapy. Nevertheless, we did not demonstrate an association between continuing DAPT and an increased risk of pocket hematoma.

Several limitations should be acknowledged. Firstly, both efficacy and safety outcomes were subjectively measured. However, we attempted to mitigate this limitation by using a standardized definition of pocket hematoma and restricting the number of observers involved in the assessment process. Secondly, we assessed the incidence of hematoma at 24 hours post-operation. The occurrences of hematoma after discharge may be underestimated, as our study did not actively monitor patients post-discharge for this complication until the 4-week follow-up. Thirdly, the decision to compare the compression device to the sandbag method was based on its historical use in our institution and its status as a standard practice at the time of the study. Comparison of compression device to other commonly used dressing methods, such as pressure dressings without the sandbag may provide a more comprehensive analysis of the device’s efficacy. In addition, the decision to have the pocket compression device worn for 16–24 hours and the sandbag compression for only 2 hours was based on the practical considerations and clinical protocols in place at the time of the study. The compression device was designed for extended use, whereas the sandbag method was intended as a temporary solution, applied for a shorter duration. This difference in the duration of application could introduce bias, as the extended wear time for the compression device may influence patient comfort and outcomes. Fourthly, our pocket compression device was tested only for transvenous CIEDs. Therefore, these results cannot be extrapolated to extravascular devices, such as the subcutaneous ICD and extravascular ICD.

Conclusions

Our novel pocket compression device demonstrated a similar effect on the occurrence of pocket hematoma compared to the conventional sandbag compression. Notably, our study revealed a very low incidence of clinically significant pocket hematoma. The importance of our results underscores the need for careful attention to prevent intraoperative bleeding during CIED implantation, regardless of the pocket compression measures employed.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Glikson, M. et al. ESC Guidelines on cardiac pacing and cardiac resynchronization therapy. Europace Eur. Pacing Arrhythm. Card. Electrophysiol. J. Work. Gr. Card. Pacing Arrhythm. Card. Cell. Electrophysiol. Eur. Soc. Cardiol. 24, 71–164. https://doi.org/10.1093/europace/euab232 (2022).

Al-Khatib, S. M. et al. 2017 AHA/ACC/HRS Guideline for management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the Prevention of Sudden Cardiac death: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 72, e91–e220. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2017.10.054 (2018).

Chien, C. Y. et al. Effectiveness of a Non-taped Compression Dress in patients receiving Cardiac Implantable Electronic devices. Acta Cardiol. Sin. 35, 320–324. https://doi.org/10.6515/acs.201905_35(3).20190107a (2019).

Awada, H., Geller, J. C., Brunelli, M. & Ohlow, M. A. Pocket related complications following cardiac electronic device implantation in patients receiving anticoagulation and/or dual antiplatelet therapy: prospective evaluation of different preventive strategies. J. Interv. Card. Electrophysiol. Int. J. Arrhythm. Pacing. 54, 247–255. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10840-018-0488-y (2019).

Fei, Y. P. et al. Effect of a Novel Pocket Compression device on hematomas following Cardiac Electronic device implantation in patients receiving direct oral anticoagulants. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 9, 817453. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcvm.2022.817453 (2022).

Hu, J., Zheng, J., Liu, X., Li, G. & Xiao, X. Effect of a pocket compression device on hematomas, skin reactions, and comfort in patients receiving a cardiovascular implantable electronic device: a randomized controlled trial. J. Interv. Card. Electrophysiol. Int. J. Arrhythm. Pacing. 63, 275–281. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10840-021-00973-5 (2022).

Essebag, V. et al. Clinically significant Pocket Hematoma increases long-term risk of device infection: Bruise Control Infection Study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 67, 1300–1308. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2016.01.009 (2016).

Sridhar, A. R. et al. Impact of haematoma after pacemaker and CRT device implantation on hospitalization costs, length of stay, and mortality: a population-based study. Europace Eur. Pacing Arrhythm. Card. Electrophysiol. J. Work. Gr. Card. Pacing Arrhythm. Card. Cell. Electrophysiol. Eur. Soc. Cardiol. 17, 1548–1554. https://doi.org/10.1093/europace/euv075 (2015).

Birnie, D. H. et al. Pacemaker or defibrillator surgery without interruption of anticoagulation. N. Engl. J. Med. 368, 2084–2093. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1302946 (2013).

Baddour, L. M. et al. Update on cardiovascular implantable electronic device infections and their management: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 121, 458–477. https://doi.org/10.1161/circulationaha.109.192665 (2010).

Kiuchi, K. et al. Novel Compression Tool to Prevent hematomas and skin erosions after device implantation. Circul. J. Off. J. Jpn. Circul. Soc. 79, 1727–1732. https://doi.org/10.1253/circj.CJ-15-0341 (2015).

Turagam, M. K., Nagarajan, D. V., Bartus, K., Makkar, A. & Swarup, V. Use of a pocket compression device for the prevention and treatment of pocket hematoma after pacemaker and defibrillator implantation (STOP-HEMATOMA-I). J. Interv. Card. Electrophysiol. Int. J. Arrhythm. Pacing. 49, 197–204. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10840-017-0235-9 (2017).

Birnie, D. H. et al. Continued vs. interrupted direct oral anticoagulants at the time of device surgery, in patients with moderate to high risk of arterial thrombo-embolic events (BRUISE CONTROL-2). Eur. Heart J. 39, 3973–3979. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehy413 (2018).

F, D. E. S., Miracapillo, G., Cresti, A., Severi, S. & Airaksinen, K. E. Pocket Hematoma: a call for definition. Pacing Clin. Electrophysiol. PACE. 38, 909–913. https://doi.org/10.1111/pace.12665 (2015).

Lattuca, B. et al. Impact of video on the understanding and satisfaction of patients receiving informed consent before elective inpatient coronary angiography: a randomized trial. Am. Heart J. 200, 67–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ahj.2018.03.006 (2018).

Lee, G. J. et al. A pilot study comparing 2 oxygen delivery methods for patients’ comfort and administration of oxygen. Respir. Care. 59, 1191–1198. https://doi.org/10.4187/respcare.02937 (2014).

The Hawthorne effect. Occup. Med. 56, 217. https://doi.org/10.1093/occmed/kqj046 (2006).

Thal, S. et al. The relationship between warfarin, aspirin, and clopidogrel continuation in the peri-procedural period and the incidence of hematoma formation after device implantation. Pacing Clin. Electrophysiol. PACE. 33, 385–388. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-8159.2009.02674.x (2010).

Tompkins, C. et al. Dual antiplatelet therapy and heparin bridging significantly increase the risk of bleeding complications after pacemaker or implantable cardioverter-defibrillator device implantation. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 55, 2376–2382. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2009.12.056 (2010).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all staffs in the Northern Cardiac Center and Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Chiang Mai University for the study’s cooperation.

Funding

This work was supported by the Faculty of Medicine Endowment Fund for medical research (Grant No.101/2566), Faculty of Medicine, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai, Thailand. The funding sources had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.P. (Narawudt) performed conception or design of the work and statistical analysis, wrote the manuscript, tables, and figures. J.Y. wrote the manuscript, tables, and figures. N.P. (Natnicha), T.N., A.P. revising it critically for important intellectual content. S.G., C.P., C.T. collected data and re-checked the data prior to the analysis. W.W. substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work, or the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of the data for the work. All authors agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Prasertwitayakij, N., Yanyongmathe, J., Pongbangli, N. et al. Effect of pocket compression device on pocket hematoma after cardiac implantable electronic device implantation. Sci Rep 15, 3214 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87735-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87735-9