Abstract

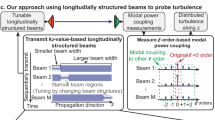

The impact of different turbulence on beams can be seen as optical distortions caused by refractive index fluctuations around vortices in turbulence. Therefore, from the perspective of transmission effects, the transmission outcomes of beam in different turbulences can be mutually equivalent. Since the mechanisms of beam propagation in compressible turbulence are not yet fully understood and the relevant theories are not well-established, a preliminary analysis of beam transmission in compressible turbulence is necessary. This analysis will help understand the medium characteristics of compressible turbulence, particularly its similarities and differences with atmospheric turbulence, before the optical effects of compressible turbulence are fully resolved. This paper establishes a connection between anisotropic atmospheric turbulence and compressible turbulence parameters by utilizing the mature solutions of beam in anisotropic atmospheric turbulence. We then employ the optical parameters of anisotropic atmospheric turbulence to represent those in compressible turbulence, leveraging existing solutions to assess beam transmission in compressible turbulence. Building upon the original equivalent method, we extend the dimension of transmission distance, ensuring that beams equivalence is maintained across different turbulence regimes. The results indicate that the equivalent method can effectively adapt to compressible turbulence. By using the equivalent structure function, it is possible to represent compressible turbulence parameters with the atmospheric refractive index structure constant. This method also works across different transmission distances. The method facilitates finding various solutions for beam in compressible turbulence.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Over the past few decades, significant advancements have been made in the study of beam transmission through atmospheric turbulence1,2,3,4, resulting in the development of numerous models of refractive index power spectrum and physical models of beam transmission in such conditions5,6,7,8,9. Atmospheric turbulence primarily degrades the performance of optical waves as they traverse turbulence vortices. The scintillation effect caused by turbulence can cause deep random fading of the optical signal at the detector, increase the bit error rate (BER) and potential signal interruptions. Scintillation index (SI) is a crucial metric for quantifying the scintillation phenomenon on beams due to turbulence and is widely employed to assess the quality of beam transmission10,11,12.

The advancement of aerospace technology has spurred extensive research into space target detection and high-speed aircraft13,14,15,16. When an aircraft flies at high speed (Ma > 1), the air surrounding an aircraft is compressed into shock waves, creating a boundary layer along aircraft’s surface. As the distance from the head increases, the boundary layer gradually becomes turbulent, and the medium around the aircraft becomes complex17. The turbulence near the surface of an aircraft differs significantly from atmospheric turbulence. Compressible turbulence generally satisfies the assumption that the air velocity is greater than the speed of sound and often occurs near the aircraft, which leads to compressible turbulence with a small range and strong fluctuation. The essential difference between compressible and atmosphere turbulence is that the velocity field divergence of compressible turbulence is not 0. The research of Xu, Guo, Mackey, Gao, et al. has shown the turbulence near the aircraft’s surface significantly impacts the quality of beam transmission18,19,20,21. Optical distortions caused by air disturbances are referred to as aero-optical effects. Compressible turbulence is distinguished by its short-range effects and large fluctuations in the refractive index. However, research on the transmission model of beam in compressible turbulence is relatively limited, and the transmission behavior of beams in compressible turbulence remains unclear. This gap in research is partly due to the compressibility in such turbulence, which arises from high fluid velocities, contrasting with classical atmospheric turbulence models that assume incompressible flow22. Therefore, before a rigorous physical model of beam transmission in compressible turbulence is established, it is essential to identify suitable methods to obtain transmission results that can help elucidate the beam’s evolution characteristics in such environments.

The research of Rabinovich, Garnier, Wu, Li, et al. indicates various turbulent media exhibit anisotropy23,24,25,26. Turbulence anisotropy reflects the degree of vortex distortion in different directions. Regardless of the type of anisotropic turbulence, beams will exhibit phenomena such as scintillation23, attenuation27, drift28, and expansion29 during transmission. If the existing formulas and results of anisotropic atmospheric turbulence can be used to correspond to the solutions of beam transmission in more complex turbulence, equivalent solutions can be obtained in advance before deriving the strict formulas for beam transmission in complex turbulence. Consequently, Yahya Baykal and Yalcin Ata have linked different turbulence parameters, using other turbulence parameters to represent atmospheric refractive index structure constant \(C_{n}^{2}\)30,31, with the goal of using \(C_{n}^{2}\) to equate other turbulence parameters, achieving the use of extensive solutions of beam transmission in atmospheric turbulence to find solutions for beam in other turbulence. The advantage of this approach lies in its ability to insert expressions for atmospheric structure parameters of anisotropic turbulence into existing physical solutions, thereby enabling the easy derivation of corresponding solutions for similar physical entities in other anisotropic turbulent environments. Thus, the equivalent method can also be applied to compressible turbulence. However, in the original method30, the transmission distances of the beam in both types of turbulence were considered consistent. In reality, though, compressible turbulence typically involves transmission distances on the meter scale, while atmospheric turbulence operates on the kilometer scale. The difference necessitates improving the equivalent method to adapt to turbulence parameters under different transmission distances.

In this paper, we use the scintillation index as an indicator of beam transmission results to establish the relationship between compressible turbulence and atmospheric turbulence. The equivalence indicator is not limited to the scintillation index; it can also include beam expansion, drift variance, and other parameters. This paper focuses on equivalence from a single perspective. By equating the effects caused by parameter changes in compressible turbulence and atmospheric turbulence on the beam, we use the extensive solutions of beam transmission in atmospheric turbulence to correspond to solutions in compressible turbulence, promoting the research of beam transmission behavior in compressible turbulence.

The first section provides an introduction to the background and implementation of the proposed method. The second section derives the scintillation index of light in compressible turbulence and details the theoretical framework of the equivalent method, which links the scintillation index of beam transmitted through atmospheric turbulence with that through compressible turbulence using the equivalent structure function. The third section presents a numerical analysis of the equivalent method to confirm its applicability across different transmission distances. The fourth section summarizes the findings of the paper.

Method

In this section, the expressions for the scintillation index of a Gaussian beam transmitted in anisotropic compressible turbulence and classical atmospheric turbulence under weak fluctuation conditions are given. The atmospheric optical turbulence parameters are used to equate the optical parameters of compressible turbulence, and the equivalent factor is obtained.

Under weak fluctuation conditions, the SI at the center of the Gaussian beam can be obtained from the variance of the logarithmic amplitude fluctuations, that is \(\sigma _{I}^{2}=4\sigma _{\chi }^{2}\)32. Under the Rytov approximation, the axial center SI of a Gaussian beam transmitted in anisotropic compressible turbulence can be expressed as32:

where \(\kappa\) is spatial wavenumber, \(\kappa ^{\prime}=\sqrt {\xi _{{x\left( {\text{C}\text{T}} \right)}}^{2}\kappa _{x}^{2}+\xi _{{y\left( {\text{C}\text{T}} \right)}}^{2}\kappa _{y}^{2}+\kappa _{z}^{2}}\), \({\kappa ^{\prime}_x},{\kappa ^{\prime}_y},{\kappa ^{\prime}_z}\) are the spatial wavenumbers in x, y, and z directions, respectively. ξx and ξy are anisotropic factors (According to the Markov approximation, the anisotropy perpendicular to the propagation axis is considered). If ξx = ξy = 1, turbulence is isotropic. \({\Phi _{n\left( {\text{C}\text{T}} \right)}}\) is the refractive index power spectral function of anisotropic compressible turbulence. \(\zeta =z/L\) is normalized distance, z is the distance on the propagation axis. L(CT) refers to the propagation distance of beam in compressible turbulence. k is optical wavenumber, \(k=2\uppi /\lambda\), \(\lambda\) is wavelength. Other parameters are expressed as

where F0 is the phase front radius of curvature and \({W_0}\) is the beam radius width. \({\Phi _{n\left( {\text{C}\text{T}} \right)}}\) is expressed as22,33

where \(\gamma\) is the ratio of specific heats for air, \({K_{GD}}\) is the Gladstone-Dale constant, \(\bar {\rho }\),\(\bar {T}\),\(\bar {P}\) is the average air density, temperature, and pressure, respectively. y is the distance of the turbulence from the aircraft, \(\bar {a}\)is the average value of sound velocity, \({B_P}\) is a dimensionless constant, \(\varepsilon\) is the turbulence dissipation rate, l is the characteristic length scale (l = L0/2π, L0 is outer scale of turbulence), R is the gas constant, \(\beta\)is a constant, and \(\chi\) is the average temperature dissipation rate.

For convenience in calculations, the constants of the refractive index spectrum of compressible turbulence can be set to

Meanwhile, simplify calculations using the following Eq.

Therefore, substituting Eqs. (3), (4), (5) and (6) into Eq. (1) yields

Integrating Eq. (7) with respect to q, we obtain

where \(\Gamma \left( \cdot \right)\) is Gamma function. Since Eq. (8) is rather complex, obtaining its analytical solution is difficult. Therefore, subsequent discussions will rely on its numerical solution. This also underscores the complexity of the formula for beam propagation in compressible turbulence and the necessity of using equivalent atmospheric turbulence parameters to explain the transmission results in compressible turbulence. The equivalent method will aid in comprehending the propagation behavior of beams in compressible turbulence.

Similarly, using Rytov theory, the SI of a Gaussian beam on axial center position during propagation in atmospheric turbulence can be expressed as

where L(AT) is the propagation distance of light in compressible turbulence, \({\Phi _{n\left( {\text{A}\text{T}} \right)}}\) is the atmospheric turbulence refractive index power spectral density function. Here, the basic form used is the anisotropic non-Kolmogorov spectrum, as described as32

where \(C_{n}^{2}\) represents the generalized atmospheric refractive index structure constant, which is a physical quantity measuring turbulence intensity. \(\alpha\) denotes the spectral power law. The refractive index spectrum assumes zero inner scale and infinite outer scale for turbulence. \(A\left( \alpha \right)\) is expressed as

Substituting Eq. (10) into Eq. (9), the expression for \(\sigma _{{I,\left( {\text{A}\text{T}} \right)}}^{2}\) as follows:

where 2F1 is the hypergeometric function, \(\sigma _{R}^{2}\) is Rytov variance, which is expressed as34

The Rytov variance fundamentally corresponds to the SI of a plane wave propagating in weak fluctuating turbulence. To find the equivalent factor, we need to equate Eq. (8) with Eq. (12), that is \(\sigma _{{I\left( {\text{C}\text{T}} \right)}}^{2}=\sigma _{{I\left( {\text{A}\text{T}} \right)}}^{2}\). Therefore, according to Eqs. (12) and (13), \(\sigma _{{I\left( {\text{A}\text{T}} \right)}}^{2}\) can be decomposed into the product of \(C_{n}^{2}\) and an equivalent factor D(\(\sigma _{{I\left( {\text{A}\text{T}} \right)}}^{2}=C_{n}^{2}D\)), yielding:

The equivalent method uses parameters of compressible turbulence to characterize the effect on SI analogous to atmospheric turbulence parameters through an equivalent factor. Additionally, compared to the original equivalent method, a new dimension of propagation distance has been introduced. This is because beams propagate shorter distances in compressible turbulence and longer distances in atmospheric turbulence. The comparison between the proposed method and the original method is shown in Table 1. Therefore, improving the equivalent method is necessary to adapt to turbulent environments with different transmission distances. However, this improved method also has limitations. It cannot equivalently account for SI variations beyond the beam center, primarily due to the different diffraction effects experienced by beam at various transmission distances.

Results

The parameters to analyze the characteristics of wave propagation are given as \(\lambda =1.06{\kern 1pt} {\kern 1pt} \upmu \text{m}\), the characteristic scale l is related to the external scale, l = L0/2π, we let l = 0.4 m. The thickness of compressible turbulence near the aircraft is generally less than 1.0 m, so we choose the optical wave transmission distance L(CT) within 1.0 m. Parameter \(\Theta\) in Gaussian beam satisfies \(0<\Theta <1\), so \(\bar {\Theta }\) satisfies \(0<\bar {\Theta }<1\), we make\(\bar {\Theta }\) = 0.5. \(R{\text{=}}8.31\text{J} \cdot {\left( {\text{m}\text{o}\text{l} \cdot \text{K}} \right)^{-1}}\) is the thermodynamic constant.\({B_p}\), \(\varepsilon\), \(\beta\), \(\chi\) are all from Refs35,36. , \({B_p} \approx 8\),\(\varepsilon {\text{=0}}{\text{0.5}}{\kern 1pt} {\kern 1pt} {{\text{m}}^2} \cdot {{\text{s}}^{{\text{-}}3}}\) ,\(\beta {\text{=}}0.8\), and\(\chi \approx 1{\kern 1pt} {\kern 1pt} {\text{K}^2} \cdot {{\text{s}}^{ - 1}}\). y is the distance of the turbulence from the wall, we do not consider the influence of the turbulent dissipation region, so y is approximately the transmission distance L(CT), \(y \approx {L_{\left( {\text{C}\text{T}} \right)}}\).

Figure 1 shows the effect of L(AT) (atmospheric transmission distance) on the atmospheric refractive index structure constant within the equivalent factor. It means that under the condition of a fixed transmission distance and turbulence parameters in anisotropic compressible turbulence, any point on the curve in Fig. 1 can be used to equate the optical parameters of compressible turbulence (LCT = 1.0 m, C2 = 10–10 m-2/3) with the optical parameters of atmospheric turbulence. From Fig. 1, it can be seen that increasing the anisotropy of the turbulence can effectively reduce the required \(C_{n}^{2}\) and the transmission distance in the equivalent factor. This indirectly indicates that increasing the turbulence anisotropy can effectively reduce the scintillation effect caused by turbulence on the beam. Moreover, with the required equivalent compressible turbulence parameters remaining constant, the atmospheric parameter \(C_{n}^{2}\) inversely changes with L(AT), meaning \(C_{n}^{2}\) and L(AT) can be interconverted.

Figure 2 shows the change in \(C_{n}^{2}\) caused by variations in L(CT) for a fixed atmospheric transmission distance. Compared to the original equivalent method, the improved method allows the transmission distance in the equivalent turbulence parameters to vary, meaning the transmission distances in the two types of turbulence can be different. Therefore, under the condition of a constant equivalent factor, increasing the transmission distance L(CT) of the equivalent turbulence parameters will increase the atmospheric refractive index structure constant \(C_{n}^{2}\). L(CT) and \(C_{n}^{2}\) are positively correlated, which physically means that increasing the transmission distance of the beam in compressible turbulence will enhance the scintillation effect of the turbulence on the beam, thereby increasing the equivalent parameters and the scintillation index of the beam transmitted in atmospheric turbulence. Moreover, increasing the anisotropy factor of the turbulence can still effectively reduce the required \(C_{n}^{2}\) in atmospheric turbulence.

Figure 3 shows the variation of the equivalent atmospheric turbulence parameter \(C_{n}^{2}\) with the compressible turbulence parameter C2 for a fixed transmission distance in both types of turbulence. When the transmission distances in the two types of turbulence are not equal, the improved equivalent method still retains the functionality of the original method. That is, with the equivalent factor remaining constant, the turbulence parameters of the two types of turbulence intensities (C2 and \(C_{n}^{2}\)) can still be mutually measured. It means that the impact caused by changes in turbulence intensity C2 during beam transmission in compressible turbulence can be mapped to changes in \(C_{n}^{2}\) during beam transmission in atmospheric turbulence.

From Figs. 1, 2 and 3, it can be observed that increasing the anisotropic factors of the turbulence can effectively reduce the scintillation effect, leading to a decrease in the equivalent parameters. We attribute the emergence of particular phenomenon to two reasons: (a) When considering the turbulent vortex as a lens, an increase in the anisotropic factor leads to an increase in the lens’s radius of curvature. This reduces the lens’s impact on the beam’s transmission path. (b) The SI in anisotropic compressible turbulence is related to the vortex structure. Increasing the anisotropic factor enlarges the vortex structure, creating regions of low air density within the vortex. Low density results in a lower refractive index. Numerous vortices with higher anisotropic factors tend to produce continuous, low-density turbulent regions along the propagation path. These continuous low-density turbulence regions improve the SI performance of the beam.

To further illustrate the applicability of using atmospheric parameters to equivalently represent compressible turbulence parameters, we can discuss the results of SI under different turbulence parameters and then use the corresponding turbulence environment with the same SI as the equivalent parameters. Figure 4 shows the variation of SI with L(AT) and \(C_{n}^{2}\), while Fig. 5 shows the variation of SI with L(CT) and C2. We use a constant SI (SI = 0.4) to illustrate the situation. The intersection of the plane \(\sigma _{{I,\left( {\text{C}\text{T}} \right)}}^{2}=\sigma _{{I,\left( {\text{A}\text{T}} \right)}}^{2}=\)0.4 [Fig. 4(a) and Fig. 5(a)]is shown in Fig. 4(b) and Fig. 5(b). The black line in Fig. 4(a) represents the intersection of the atmospheric turbulence parameters L(AT) -\(C_{n}^{2}\) on the plane \(\sigma _{{I,\left( {\text{A}\text{T}} \right)}}^{2}\)= 0.4, and the red line in Fig. 5(a) represents the intersection of the compressible turbulence parameters L(CT) - C2 on plane \(\sigma _{{I,\left( {\text{C}\text{T}} \right)}}^{2}\)= 0.4. Thus, any point on the red line can be equivalently represented by any point on the black line, with the corresponding SI being constant. It means that any combination of L(CT) and C2 on the red line can be equivalently represented by any combination of L(AT) and \(C_{n}^{2}\) on the black line. This equivalence is not unique, a combination of compressible optical turbulence parameters can be equivalently represented by numerous combinations of atmospheric turbulence parameters, and vice versa. The mutual equivalence relationship means that for a measured scintillation index in compressible turbulence, one can directly use the intersection plane SI = constant to obtain the required equivalent atmospheric turbulence parameters. Therefore, the improved equivalent turbulence parameter method not only incorporates the dimension of transmission distance but also significantly enhances the applicability of the equivalent method.

Conclusion

In this paper, we developed an improved equivalent turbulence method to represent anisotropic atmospheric turbulence structure parameters in anisotropic compressible turbulence. The method equates the optical parameters in compressible turbulence to those in atmospheric turbulence using the SI as an indicator. The improved equivalent method liberates beam from the constraint of equal transmission distances between two types of turbulence, adapting to the characteristics of compressible turbulence with a small range and significant turbulence disturbance. By extending the dimension of transmission distance, the equivalent method simplifies complex derivations and calculations needed to obtain beam transmission results in anisotropic compressible turbulence, aiding in finding solutions for light in compressible turbulence. The results indicate that increasing the distance over which a beam travels through the atmosphere turbulence increases the equivalent structure constant, thereby reducing the equivalent \(C_{n}^{2}\). Increasing the distance and turbulence intensity of beam propagation in compressible turbulence significantly enhances the equivalent \(C_{n}^{2}\). Increasing the anisotropy of turbulence effectively reduces the equivalent \(C_{n}^{2}\) required. In summary, we use the optical solution of atmospheric turbulence to equate the optical solution of compressible turbulence, and obtains the transmission results of beam in compressible turbulence in a simpler way, which helps to clear the transmission behavior of beam in compressible turbulence.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Kaushal, H. & Kaddoum, G. Optical communication in space: challenges and mitigation techniques. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tut. 19, 57–96. https://doi.org/10.1109/COMST.2016.2603518 (2017).

Jumper, E. J. & Gordeyev, S. Physics and measurement of aero-optical effects: past and present. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 49, 419–441. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-fluid-010816-060315 (2017).

Khalighi, M. A. & Uysal, M. Survey on free space optical communication: a communication theory perspective. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tut. 16, 2231–2258. https://doi.org/10.1109/COMST.2014.2329501 (2014).

Wu, X., Wang, C., Kong, Y. & Wu, K. Beam intensity and spectral coherence of Hermite-Cosine-Gaussian rectangular multi-gaussian correlated Schell-model beam in oceanic turbulence. Heliyon 9, e18374. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e18374 (2023).

An, K. The local structure of turbulence in incompressible viscous fluid for very large Reynolds’ numbers. Dokl. Akad. Nauk. SSSR 30, 299–303 (1941).

Toselli, I., Andrews, L., Phillips, R. & Ferrero, V. Angle of arrival fluctuations for free space laser beam propagation through non Kolmogorov turbulence. Proc. SPIE Int. Soc. Opt. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1117/12.719033 (2007).

Andrews, L. C. An analytical model for the refractive index power spectrum and its application to optical scintillations in the atmosphere. J. Mod. Opt. 39, 1849–1853. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500349214551931 (1992).

H. R. Models of the scalar spectrum for turbulent advection. J. Fluid Mech. 88, 541–562. https://doi.org/10.1017/S002211207800227X (1978).

Tatarskii, V. I. The effects of the turbulent atmosphere on wave propagation, Israel Program for Scientific Translations, U.S. Dept. of Commerce, NTIS No. TT 68-504-64 (1971).

Kolosov, V. V., Kulikov, V. A. & Polnau, E. Dependence of the probability density function of laser radiation power on the scintillation index and the size of a receiver aperture. Opt. Express 30, 3016–3034. https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.444958 (2022).

Beason, M., Gladysz, S. & Andrews, L. Comparison of probability density functions for aperture-averaged irradiance fluctuations of a gaussian beam with beam wander. Appl. Opt. 59, 6102–6112. https://doi.org/10.1364/AO.391938 (2020).

Aksenov, V. P., Dudorov, V. V., Kolosov, V. V. & Venediktov, V. Y. Probability distribution of intensity fluctuations of arbitrary-type laser beams in the turbulent atmosphere. Opt. Express 27, 24705–24716. https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.27.024705 (2019).

Sutton, G. W. Aero-optical foundations and applications. AIAA J. 23, 1525–1537. https://doi.org/10.2514/3.9120 (1985).

Wyckham, C. M. & Smits, A. J. Aero-optic distortion in transonic and hypersonic turbulent boundary layers. AIAA J. 47, 2158–2168. https://doi.org/10.2514/1.41453 (2009).

Liu, Y. et al. Influence of non-uniform airflow on optical deformation measurement in subsonic conditions. Opt. Lasers Eng. 122, 254–264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.optlaseng.2019.06.009 (2019).

Dai, S. et al. Tunable narrow-linewidth 226 nm laser for hypersonic flow velocimetry. Opt. Lett. 45, 2291–2294. https://doi.org/10.1364/OL.390347 (2020).

Lee, C. & Chen, S. Recent progress in the study of transition in the hypersonic boundary layer. Natl. Sci. Rev. 6, 155–170. https://doi.org/10.1093/nsr/nwy052 (2019).

Xu, L., Xin, Y., Zhou, Z., Ren, T. & Han, B. Propagation characteristics of orbital angular momentum and its time evolution carried by a Laguerre-Gaussian beam in supersonic turbulent boundary layer. Opt. Express 28, 4032–4047. https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.382421 (2020).

Guo, G., Zhu, L. & Bian, Y. Numerical analysis on aero-optical wavefront distortion induced by vortices from the viewpoint of fluid density. Opt. Commun. 474. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.optcom.2020.126181 (2020).

Mackey, L. E. & Boyd, I. D. Assessment of hypersonic flow physics on aero-optics. AIAA J. 57, 3885–3897. https://doi.org/10.2514/1.J057869 (2019).

Gao, Q., Yi, S., Jiang, Z., He, L. & Zhao, Y. Hierarchical structure of the optical path length of the supersonic turbulent boundary layer. Opt. Express 20, 16494–16503. https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.20.016494 (2012).

Xie, J., Bai, L., Wang, Y. & Guo, L. Refractive index fluctuation spectrum of lightwave propagation in supersonic compressible turbulent flow. Wave Random Complex, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/17455030.2022.2032473 (2022).

Rabinovich, W. S., Mahon, R. & Ferraro, M. S. Optical scintillation in a maritime environment. Opt. Express 31, 10217. https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.484922 (2023).

Garnier, J. & Sølna, K. Scintillation of partially coherent light in time-varying complex media. J. Opt. Soc. Am. A 39, 1309. https://doi.org/10.1364/JOSAA.453358 (2022).

Wu, X., Mao, X. & Wu, K. Propagation of Lorentz-Gaussian elliptical multi-gaussian correlated Schell-Model beam in anisotropic turbulence. Heliyon 9, e13501. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e13501 (2023).

Li, J., Yang, S., Guo, L. & Cheng, M. Anisotropic power spectrum of refractive-index fluctuation in hypersonic turbulence. Appl. Opt. 55, 9137–9144. https://doi.org/10.1364/AO.55.009137 (2016).

Zang, Q. et al. Laboratory simulation of laser propagation through plasma sheaths containing ablation particles of ZrB2-SiC-C during hypersonic flight. Opt. Lett. 42, 687–690. https://doi.org/10.1364/OL.42.000687 (2017).

Chen, M. et al. Simulating non-kolmogorov turbulence phase screens based on equivalent structure constant and its influence on simulations of beam propagation. Results Phys. 7, 3596–3602. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rinp.2017.09.034 (2017).

Song, Y., Zhang, B. & He, A. Algebraic iterative algorithm for deflection tomography and its application to density flow fields in a hypersonic wind tunnel. Appl. Opt. 45, 8092–8101. https://doi.org/10.1364/AO.45.008092 (2006).

Baykal, Y., Ata, Y. & Gokce, M. C. Structure parameter of anisotropic atmospheric turbulence expressed in terms of anisotropic factors and oceanic turbulence parameters. Appl. Opt. 58, 454–460. https://doi.org/10.1364/AO.58.000454 (2019).

Baykal, Y. Expressing oceanic turbulence parameters by atmospheric turbulence structure constant. Appl. Opt. 55, 1228–1231. https://doi.org/10.1364/AO.55.001228 (2016).

Andrews, L. & Phillips, R. Laser Beam Propagation Through Random Media. https://doi.org/10.1117/3.626196 (SPIE, 2005).

Xie, J., Bai, L., Wang, Y. & Guo, L. Transmittance and energy transfer of Gaussian Beam propagation in anisotropic compressible turbulence. Wave Random Complex 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/17455030.2022.2157514 (2022).

Andrews, L. C., Phillips, R. L. & Crabbs, R. Propagation of a Gaussian-beam wave in general anisotropic turbulence, Laser Communication and Propagation through the Atmosphere and Oceans III. https://doi.org/10.1117/12.2061892 (2014).

Gotoh, T. & Fukayama, D. Pressure spectrum in homogeneous turbulence. Phys. Rev. Lett. 86, 3775–3778. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.86.3775 (2001).

Kaiser, R. & Fedorovich, E. Turbulence spectra and dissipation rates in a wind tunnel model of the atmospheric convective boundary layer. J. Atmos. Sci. 55, 580–594 (1998).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of Fujian Province (2024J01901) and Sanming University’s Scientific Research Initiation Grants for Introduced High-level Talents (project no. 24YG06).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Wenjie Wu: Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Project administration; Jingyu Xie: Investigation, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization, Software, Data Curation, Writing-Original Draft, Validation, Conceptualization; Lu Bai: Resources, Validation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, W., Xie, J. & Bai, L. Improved equivalent optical turbulence method for anisotropic compressible and atmospheric turbulence under different beam transmission distances. Sci Rep 15, 3394 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87849-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87849-0