Abstract

This study aimed to evaluate the usefulness of amplicon-based real-time metagenomic sequencing applied to cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) for identifying the causative agents of bacterial meningitis. We conducted a 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing using a nanopore-based platform, alongside routine polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing or bacterial culture, to compare its clinical performance in pathogen detection on CSF samples. Among 17 patients, nanopore-based sequencing, multiplex PCR, and bacterial culture detected potential bacterial pathogens in 47.1%, 0%, and 47.1% samples, respectively. Nanopore-based sequencing demonstrated a sensitivity of 50.0%, specificity of 55.6%, positive predictive value of 50.0%, negative predictive value of 55.6%, and overall accuracy of 47.1%, compared to the gold standard method for bacterial culture. In 44.4% (4/9) of culture-negative cases, nanopore-based sequencing detected potentially causative pathogens, whereas four (23.5%) patients were positive only in culture. Using nanopore-based sequencing alongside bacterial culture increased the positivity rate from 47.1 to 70.6%. However, these values may be overestimated due to challenges in distinguishing significant pathogens from background noise. Meanwhile, the bioinformatics module in EPI2ME reduced the turn-around time to 10 min. Nanopore-based metagenomic sequencing is expected to serve as a complementary tool for pathogen detection in CSF samples by facilitating rapid and accurate diagnosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The rapid and accurate identification of pathogenic microorganisms in patients with infectious diseases is a fundamental element of optimized care for treatment and epidemiological surveillance1. Despite dramatic advances in diagnostic technology, many patients suspected of having an infectious disease continue to receive empirical antibiotics instead of definitive antibiotics against the identified causative bacteria.

For over 100 years, time-consuming microbial cultures have been the gold standard for identifying the causative agents of many infectious diseases. However, the constant demand for faster, more accurate, and user-friendly testing methods in clinical settings has led to remarkable developments in molecular diagnostics2. Introducing these tests for rapid, on-demand use at point-of-care outside well-equipped large-scale laboratories is challenging3.

The MinION sequencer, a third-generation sequencing platform produced by Oxford Nanopore Technologies, can generate real-time sequencing data for long reads on a simple, portable, low-cost platform4. Thus, it has long-term potential as a point-of-care test for infectious diseases in clinical settings5. Nanopore sequencing has been successfully used to investigate outbreaks caused by emerging or reemerging pathogens6,7.

Acute bacterial meningitis, which can rapidly deteriorate, is a life-threatening medical emergency requiring timely medical attention8. Although cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) culture is the gold standard for diagnosing bacterial meningitis, polymerase chain reaction (PCR), which plays an auxiliary role in CSF analysis, can be more useful, particularly in patients receiving antibiotic treatment before lumbar puncture9. Studies on sequencing-based diagnosis of meningitis are ongoing worldwide10,11,12. Previous studies evaluating the clinical performance of nanopore-based sequencing have suggested the potential of MinION for on-site diagnosis of meningitis12,13,14,15,16,17,18. However, whether this platform can be applied clinically remains unclear.

This study aimed to detect the suspected causative pathogens in CSF samples of patients using nanopore-based metagenomic sequencing and compare the clinical performance of nanopore-based sequencing directly applied to CSF with routine culture methods or commercial multiplex molecular panels for pathogen detection.

Results

Clinical characteristics of patients

CSF samples were collected from 17 hospitalized patients with suspected meningitis. The mean age of the patients was 56 years (range, 23–85 years), with 58.8% being male. The clinical characteristics of these patients, including diagnosis, blood-culture results, CSF cell counts, and glucose and protein levels, are summarized in Table 1.

Pathogens identified using MinION-based metagenomic sequencing

After 5 h of sequencing, 1,041,355 reads were obtained, 155,893 (15.0%) of which were sorted into 17 samples based on the barcodes designed for SQK-NBD114.24. The average length of the sequencing reads with barcodes was 1331 base pairs (bp). For each sample, the EPI2ME 16S analysis software predicts the bacterial species at different calculation times. The details of the bacterial species identified at ≥ 0.048% of the proportion of the entire reads at 5 h are shown in Table 2.

The sequencing results for three of the eight culture-positive samples were consistent with those obtained using conventional culture-based methods. However, one of the eight culture-positive samples showed different bacteria compared with the results obtained using the culture-based method, and no bacteria were detected in the other four culture-positive samples. In addition, two culture-positive samples containing multiple bacterial species were detected with reads ≥ 0.048%. Four of the nine culture-negative samples—Cutibacterium acnes, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Shingomonas echinoides, Enterococcus faecalis, Enterococcus avium, and Enterococcus hirae—were detected by MinION sequencing; these were the bacteria that were duplicated more than twice among the three repeated results and ranked in the top three. In contrast, the negative control yielded 4–11 bacterial reads per run. Among the bacterial reads, Methylobacterium hispanicum, C. acnes, Enterococcus faecium, E. hirae, Streptococcus agalactiae, Staphylococcus roterodami, and Staphylococcus saccharolyticus were predominant in the samples from the same run.

Diagnostic performance of MinION-based metagenomic sequencing

Examination of CSF specimens collected from 17 patients with potentially pathogenic bacteria revealed a positivity rate of 47.1% (8/17) using MinION sequencing. Based on the gold standard culture results, of the eight culture-positive samples, four (50.0%) were identified as positive using the MinION sequencer, and the pathogens were completely consistent in three (75.0%) of these patients, ranking among the top in all three repetitions. One sample (patient 15 in Table 2) exhibited different bacteria, C. acnes, compared to the culture results, which was a common contaminant during a lumbar puncture. Of the four remaining samples, one sample (patient 13 in Table 2) showed partial concordance, matching the culture results only once in three replicates. No bacteria were detected in the other three samples owing to < 0.048% background noise filtering. Finally, it showed a sensitivity of 50.0% (95% confidence interval [CI] 15.7–84.3%) with a positive predictive value of 50.0% (95% CI 26.8–73.2%). Among the nine culture-negative samples, four (44.4%) displayed positive potential pathogen results, resulting in a specificity of 55.6% (95% CI 21.2–86.3%) and a negative predictive value of 55.6% (95% CI 33.6–75.6%). Herpes simplex virus (HSV) and varicella-zoster virus (VZV) were detected in two CSF samples using routine PCR-based testing.

Of the 17 samples, nine were exposed to antibiotics before CSF examination. Among the nine samples, potentially causative pathogens were detected in six and three samples using conventional culture methods and nanopore sequencing, respectively. Additionally, the pathogen was identified using nanopore sequencing in only one culture-negative sample (patient 9 in Table 2). However, there were discrepant results between blood culture and 16S rDNA sequencing.

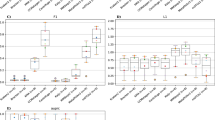

Turn-around time for Nanopore MinION sequencing

To assess the sequencing time required to identify the causative bacterial species, sequencing data at seven different time points (3 min, 5 min, 10 min, 30 min, 1 h, 3 h, and 5 h) from the beginning of MinION sequencing are summarized (Table 3). All major bacterial species considered potentially causative pathogens were detected within 10 min of sequencing (Table 3). The minimum time required for the nanopore sequencing process in our study was as follows: 1.5 h for DNA extraction, 2.5 h for 16S rDNA PCR and purification, 2.3 h for library preparation, 10 min for sequencing, and 10 min for bioinformatics analysis. A single run of Nanopore MinION sequencing detected potentially causative pathogens at the species level within an average of 1 h.

Discussion

Our study suggests that nanopore sequencing can overcome the limitations of classical diagnostic techniques by improving pathogen recognition and rapidly detecting pathogens directly in clinical samples as a potential point-of-care testing device. However, the low sensitivity, specificity, and relatively high error rates make it challenging to improve the reliability of nanopore sequencing.

In our study, nanopore sequencing was helpful in detecting bacteria at the species level in CSF samples. Although such a high resolution may increase the risk of false-positive detections, nanopore sequencing takes potential advantage of the real-time detection of unknown or uncultivable bacterial species. However, when analyzing specimens exposed to antibiotics before CSF testing, our findings demonstrated that nanopore sequencing did not show better clinical performance than conventional culture-based testing. This is thought to be caused by unidentified technical limitations within the workflow rather than simply a problem with the amount of purified DNA or the total read count. In our analysis, after conducting the experiment three times on 17 samples, an average of 20,418 (range, 2,376–55,879) reads per sample was obtained; however, the number of reads matched with the potentially causative pathogens averaged 3,413 (range 0–51,168). In other words, only 0.048–31.01% of the total reads identified in each specimen were associated with causative pathogens. A critical limitation of nanopore sequencing is the need for relatively large amounts of samples19. Several studies have suggested the utility of nanopore sequencing for pathogen detection in diverse clinical specimens with high pathogen loads20,21,22.

In our study, the nanopore sequencing approach alone showed a sensitivity of 50.0%, specificity of 55.6%, positive predictive value of 50.0%, and negative predictive value of 55.6%, based on the gold standard of bacterial culture. Our analysis set the criteria for a positive result based on the presence of bacteria ranked in the top three at least twice among triplicates. These criteria could have reduced the chance of false positives. Previous studies have not accurately evaluated the clinical performance of nanopore sequencing; however, the overall consistency between nanopore sequencing and the gold standard of bacterial culture ranged from 66.7–70%, which was better than the 47.1% in our study15,16,23. Particularly, implementing a molecular-based approach as a diagnostic tool complementary to conventional culture-based methods may increase the yield of pathogen detection, as the positivity rate improved from 47–70% and 40–57% in our study and a previous study, respectively16. However, in culture-negative cases, the possibility that pathogens detected by nanopore sequencing are contaminants should also be considered.

As shown in our study, multiplex PCR-based testing plays a limited role in identifying the causative bacteria in various types of meningitis. However, they are useful for identifying potential pathogens for viral meningitis/encephalitis cases, such as in the cases where HSV type 1 and VZV were detected in patients 2 and 3, respectively. However, the strength of nanopore sequencing is its ability to identify pathogens that are not included in multiplex PCR-based testing and have not been previously suspected in patients. If supported by more extensive and user-friendly bioinformatics platforms, its auxiliary application may allow ultrafast identification of pathogenic microorganisms on-site, including difficult-to-cultivate and rare pathogens. Nanopore sequencing of multiple samples can be simultaneously performed by applying different barcodes to each sample.

The most notable advantage of nanopore sequencing is its rapid turnaround time. In our study, nanopore sequencing significantly reduced the lead time required to identify pathogens to 7 h compared to conventional culture studies, which generally require > 72 h. Meanwhile, the minimum sequencing time for pathogen detection was 10 min. Sequencing data were analyzed at seven different time points (3 min, 5 min, 10 min, 30 min, 1 h, 3 h, and 5 h) from the beginning of the MinION sequencing. In all cases, the amount of information that aligned with the pathogens remained unchanged after 10 min of nanopore sequencing. Rapid identification of the pathogen will enable early administration of optimal antibiotics, which will improve clinical outcomes, attenuate the drivers of antimicrobial resistance, and contribute to reducing medical costs by avoiding unnecessary tests.

Our study has some limitations. First, it had a small sample size owing to the limited number of patients with suspected meningitis who were admitted to the hospital. Second, the diagnostic workflow relied heavily on reference databases of previously sequenced microorganisms and incomplete computational resources. Therefore, the sequencing library preparation workflow needs to be continuously improved to achieve precise pathogen identification in clinical practice. To ensure the accuracy and reliability of species identification, alternative classification software or pipelines may be attempted. Third, this protocol requires high-purity and high-concentration DNA for reliable sequencing. However, owing to the nature of CSF samples, the amount of nucleic acids in CSF samples may be very small, which can impact the ability to generate 16S rDNA amplicons and result in low-quality libraries and sequencing data. Furthermore, avoiding DNA loss during the experiment was difficult, and the space or processes used were not sterile. Each step of the process must be standardized and validated. Fourth, samples with pathogens identified using culture or nanopore sequencing were not validated using a third assay. Distinguishing clinically significant pathogens from contamination or colonization amid background noise remains challenging. In addition, barcode bleedover, the relatively lower read accuracy of Oxford Nanopore data compared to other NGS platforms, and the misassignment of reads during bioinformatics analysis can impede the accurate identification of pathogens. This study serves as a cornerstone for future prospective, large-scale studies exploring the clinical value of this approach in routine practice.

Conclusion

In addition to routine laboratory diagnostic procedures, nanopore sequencing may complement rapid pathogen identification, especially those that are difficult to culture. In addition to improving diagnostic speed and accuracy, the development of more miniaturized and cost-effective nanopore sequencing tools is expected to expand the scope of clinical applications. However, large-scale trials and further translational research in clinical settings are needed to validate these findings.

Materials and methods

Hospital setting and study design

This retrospective study was conducted in a 1,048-bed university-affiliated hospital in Korea from July 2020 to July 2023. The Institutional Review Board of Korea University Anam Hospital (Approval no. 2020AN0208) approved the study design and methods. This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical guidelines and regulations of the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from patients or their guardians.

Patients and clinical samples

Clinical CSF samples were obtained via lumbar puncture, performed by healthcare workers based on patients’ clinical indications. The pathogen detection workflow for the CSF specimens is shown in Fig. 1. Specimens were sent to a routine clinical diagnostic laboratory. All CSF samples were manually counted for white and red blood cells, polymorphonuclear leukocytes, and lymphocytes using a hemocytometer. CSF glucose and protein levels were measured using an AU5800 Series Clinical Chemistry Analyzer (Beckman Coulter Inc., Fullerton, CA, USA). They were tested to identify the causative agents of meningitis based on the clinical standard operating protocol, using routine culturing methods and multiplex PCR-based testing. Routine cultures were performed by inoculating into blood agar or chocolate agar plate under aerobic conditions or thioglycollate broth under anaerobic conditions and incubating at 37 ℃ for 48 h24. If bacteria grew in the medium, a subsequent test using a MicroScan WalkAway-96 Plus system (Beckman Coulter, Inc., CA, USA) was performed to identify the strain; otherwise, it was labeled as “no growth.” Multiplex PCR-based testing can detect the following five bacteria of Streptococcus pneumoniae, Hemophilus influenza type B, Neisseria meningitidis, Group B Streptococcus, Listeria monocytogenes, as well as seven viruses of HSV, Enterovirus, VZV, Epstein Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, and human herpesvirus, using traditional PCR (SEEAMP™ PCR system, Seegene, China) or RT-qPCR (Exicycler™ 96, Bioneer, Korea)25,26. However, multiplex PCR could not be performed for all patients owing to the limited number of specimens obtained and the lack of patient consent owing to the test’s cost.

Schematic of the nanopore sequencing workflow for identification of the causative pathogens in CSF samples of patients suspected of meningitis. (A) WBC and RBC counts and glucose and protein levels were analyzed for clinical samples of CSF. (B) After CSF analysis, the multiplex PCR-based testing determined whether they harbored the following bacteria: Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenza type B, Neisseria meningitidis, Group B Streptococcus, and Listeria monocytogenes. (C) Per routine diagnosis, conventional culture tests were performed on all CSF and blood samples. After that, for bacterial identification, they were initially analyzed using MALDI-TOF MS. According to the results, they were subsequently double-checked by the automated bacterial identification and susceptibility testing system. (D) The 16 s rRNA amplicon-based metagenomic sequencing was performed using MinION nanopore sequencing through DNA extraction, PCR amplification of the 16s rDNA gene, and library preparation. MinION-generated data was analyzed based on the NCBI database using the EPI2ME online software. Abbreviations: CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; MALDI-TOF MS, matrix-assisted laser desorption-ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry; RBC, red blood cell; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; WBC, white blood cell.

According to routine culturing methods, bacterial species were identified using matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF Biotyper® Sirius IVD version 4.2.100; Bruker Daltonics GmbH, Bremen, Germany). In parallel with strain identification using MALDI-TOF MS, a MicroScan WalkAway-96 Plus system (v4.43; Beckman Coulter, Inc., Fullerton, CA, USA) and an Automated Microbial Identification and Susceptibility Test System VITEK 2® MS (v9.02; bioMérieux, Marcy-l’Étoile, France) were used for re-confirmation of gram-positive cocci and gram-negative bacilli identification, respectively. Simultaneously, the specimens were divided into 1-mL aliquots and frozen at –80 ℃ for retrospective nanopore metagenomic sequencing until they were used prior to DNA preparation. Nanopore sequencing of all samples was performed in triplicates.

Preparation of DNA libraries

A DNA extraction protocol combining rapid mechanical and chemical lysis was performed as follows: First, each 1-mL aliquot of CSF was centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 5 min, and 800 µL of supernatant was discarded. In the remaining solution, 500 µL of DNA extraction buffer (1 M NaCl, 8 mL; 1 M Tris–HCl [pH 8.0], 8 mL; 0.5 M EDTA [pH 8.0], 1.6 mL; distilled water, 22.4 mL), 210 µL of 20% SDS, and 0.25 g (250 µL) of 0.1 mm zirconia/silica beads (BioSpec Products™; Bartlesville, CA, USA) were added and incubated for 30 min at room temperature. After incubation, 500 µL of phenol–chloroform-isoamyl alcohol was added to the reaction solution and mixed thoroughly for 10 min with Vortex-Genie 2 (Scientific Industries, Inc., Bohemia, NY, USA) and centrifuged at 8,000 rpm for 3 min. Then, DNA purification was processed with a MagListo® 5 M Genomic DNA Extraction Kit (Bioneer, Daejeon, South Korea) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and the extracted DNA was quantified using a Qubit 4.0 fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

For each sample, PCR amplification of 16S rDNA was conducted using the LongAmp® Taq 2X Master Mix (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. In brief, the PCR of the 16S rDNA gene with universal primers 27F (5′-AGAGTTTGATCMTGGCTCAG-3′) and 1492R (5′-TACGGYTACCTTGTTACGACTT-3′) contained 12.5 µL of LongAmp® Taq 2X Master Mix, 1 µL of all primers (10 pmol/µL), and 2 µL of eluted DNA, brought up to a final volume of 25 µL with nuclease-free water. The PCR cycle condition was an initial denaturation at 94 ℃ for 1 min; 35 cycles of 95 ℃ for 20 s, 55 ℃ for 30 s, and 65 ℃ for 75 s (50 s/kb); and a final extension at 72 ℃ for 10 min. All PCR reactions were performed using a T100 thermal cycler (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). All PCRs were performed with a negative control (distilled water) and a positive control (bacterial genomic DNA; Klebsiella pneumoniae). Further, all PCR products were purified with AMPure XP Beads (Beckman Coulter Inc., Fullerton, CA, USA).

The products were electrophoresed on a 1.5% agarose gel containing RedSafe™ Nucleic Acid Staining Solution (20.000×) (Intron Biotechnology, Boston, MA, USA) and visualized using a PrepOne™ Sapphire Blue LED Illuminator (Embi Tec, San Diego, CA, USA). When the PCR product of the negative control showed a PCR-positive band, indicating contamination, PCR was repeated from the beginning.

16S rRNA amplicon-based metagenomic sequencing

To identify bacterial pathogens in CSF specimens within a short time using a simple procedure, the MinION nanopore sequencer was applied to clinical specimens in three consecutive runs per specimen. Up to 200 ng of each purified DNA fragment was used for barcoding and the preparation of sequencing libraries using the Native Barcoding Kit 24 V14 (SQK-NBD114.24; Oxford Nanopore Technologies, Oxford, UK) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

For sequencing on a MinION device, the DNA library was loaded into a MinION flow cell (FLO-MIN114, R10.4.1 version) with 1,400 available pores. Finally, raw data acquisition and live base-calling were performed in super-accuracy mode using the MinKNOW Oxford Nanopore Technologies software (v23.11.4). The experiment was repeated three times for each of the 17 samples using a new barcode from 16s rDNA amplicon generation through library preparation and sequencing. This protocol allows up to 24 CSF samples to be sequenced in a single MinION flow cell. After sequencing, the flow cell was cleaned using a Flow Cell Wash Kit (EXP-WSH004; Oxford Nanopore Technologies, Oxford, UK) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Analysis of MinION sequence data

Raw nanopore data from the FAST5 reads were continuously collected during sequencing. FASTQ generation was performed using the ONT Dorado software (v7.2.13), and each FASTQ file per Oxford Nanopore Technologies barcode data was used for downstream analysis.

To identify the species, the dataset of each FASTA read was analyzed in real-time using Fastq 16S via EPI2ME Agent (v3.7.3; Metrichor, Oxford, UK) (https://epi2me.nanoporetech.com/user), cloud-based analysis, and a taxon prediction program. The Fastq 16S workflow used read mapping to reference sequences in the National Centre for Biotechnology Information database to identify bacterial species. The proportion of sorted reads mapped to a bacterial reference was used to determine potential pathogens in each sample. Bacterial reads from clinical samples detected in lower proportions than those in the corresponding negative controls were excluded from further analysis. In contrast, the highest ratio of read counts for isolated bacteria to total read counts identified in the negative control was 0.047%. Thus, they were considered background noise due to their < 0.048% abundance.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript. Data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Galar, A. et al. Clinical and economic evaluation of the impact of rapid microbiological diagnostic testing. J. Infect. 65, 302–309. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinf.2012.06.006 (2012).

Liu, Q. et al. Advances in the application of molecular diagnostic techniques for the detection of infectious disease pathogens (review). Mol. Med. Rep. 27, 104. https://doi.org/10.3892/mmr.2023.12991 (2023).

Chen, H., Liu, K., Li, Z. & Wang, P. Point of care testing for infectious diseases. Clin. Chim. Acta. 493, 138–147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cca.2019.03.008 (2019).

Lu, H., Giordano, F. & Ning, Z. Oxford nanopore MinION sequencing and genome assembly. Genom. Proteomics Bioinform. 14, 265–279. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gpb.2016.05.004 (2016).

Zhang, L. L., Zhang, C. & Peng, J. P. Application of nanopore sequencing technology in the clinical diagnosis of infectious diseases. Biomed. Environ. Sci. 35, 381–392. https://doi.org/10.3967/bes2022.054 (2022).

Quick, J. et al. Real-time, portable genome sequencing for Ebola surveillance. Nature. 530, 228–232. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature16996 (2016).

Kafetzopoulou, L. E. et al. Metagenomic sequencing at the epicenter of the Nigeria 2018 Lassa fever outbreak. Science 363, 74–77. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aau9343 (2019).

GBD 2019 Meningitis Antimicrobial Resistance Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of meningitis and its aetiologies, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet Neurol. 22, 685–711. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(23)00195-3 (2023).

Sharma, N. et al. Clinical use of multiplex-PCR for the diagnosis of acute bacterial meningitis. J. Family Med. Prim. Care. 11, 593–598. https://doi.org/10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_1162_21 (2022).

Miller, S. et al. Laboratory validation of a clinical metagenomic sequencing assay for pathogen detection in cerebrospinal fluid. Genome Res. 29, 831–842. https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.238170.118 (2019).

Zhang, X. X. et al. The diagnostic value of metagenomic next-generation sequencing for identifying Streptococcus pneumoniae in paediatric bacterial meningitis. BMC Infect. Dis. 19, 495. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-019-4132-y (2019).

Wilson, M. R. et al. Clinical metagenomic sequencing for diagnosis of meningitis and encephalitis. N. Engl. J. Med. 380, 2327–2340. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1803396 (2019).

Moon, J. et al. Rapid diagnosis of bacterial meningitis by nanopore 16S amplicon sequencing: A pilot study. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 309, 151338. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmm.2019.151338 (2019).

Jang, Y. et al. Nanopore 16S sequencing enhances the detection of bacterial meningitis after neurosurgery. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 9, 312–325. https://doi.org/10.1002/acn3.51517 (2022).

Bouchiat, C. et al. Improving the diagnosis of bacterial infections: Evaluation of 16S rRNA nanopore metagenomics in culture-negative samples. Front. Microbiol. 13, 943441. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2022.943441 (2022).

Pallerla, S. R. et al. Diagnosis of pathogens causing bacterial meningitis using nanopore sequencing in a resource-limited setting. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 21, 39. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12941-022-00530-6 (2022).

Horiba, K. et al. Performance of nanopore and illumina metagenomic sequencing for pathogen detection and transcriptome analysis in infantile central nervous system infections. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 9, 504. https://doi.org/10.1093/ofid/ofac504 (2022).

Morsli, M. et al. Real-time metagenomics-based diagnosis of community-acquired meningitis: A prospective series, southern France. EBioMedicine. 84, 104247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ebiom.2022.104247 (2022).

Chapman, R. et al. Nanopore-based metagenomic sequencing in respiratory tract infection: A developing diagnostic platform. Lung. 201, 171–179. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00408-023-00612-y (2023).

Ashikawa, S. et al. Rapid identification of pathogens from positive blood culture bottles with the MinION nanopore sequencer. J. Med. Microbiol. 67, 1589–1595. https://doi.org/10.1099/jmm.0.000855 (2018).

Charalampous, T. et al. Nanopore metagenomics enables rapid clinical diagnosis of bacterial lower respiratory infection. Nat. Biotechnol. 37, 783–792. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-019-0156-5 (2019).

Yang, L. et al. Metagenomic identification of severe pneumonia pathogens in mechanically-ventilated patients: A feasibility and clinical validity study. Respir. Res. 20, 265. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-019-1218-4 (2019).

Nakagawa, S. et al. Rapid sequencing-based diagnosis of infectious bacterial species from meningitis patients in Zambia. Clin. Transl. Immunol. https://doi.org/10.1002/cti2.1087 (2019).

Dunbar, S. A., Eason, R. A., Musher, D. M. & Clarridge, J. E. Microscopic examination and broth culture of cerebrospinal fluid in diagnosis of meningitis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36, 1617–1620. https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.36.6.1617-1620.1998 (1998).

Corless, C. E. et al. Simultaneous detection of Neisseria meningitidis, Haemophilus influenzae, and Streptococcus pneumoniae in suspected cases of meningitis and septicemia using real-time PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39, 1553–1558. https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.39.4.1553-1558.2001 (2001).

Tavakolian, S. et al. Detection of Enterovirus, Herpes Simplex, Varicella Zoster, Epstein-Barr and Cytomegalovirus in cerebrospinal fluid in meningitis patients in Iran. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcla.23836 (2021).

Funding

This work was supported by grants from Yuhan Co., Seoul, Korea (Grant number: Q2021541) and the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI), funded by the Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea (Grant number: HI23C1297). Funding sources played no role in the study design, data collection, data analysis, decision to publish, or manuscript preparation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YHS: Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Visualization, Validation, Writing – Review & Editing; YKJ: Methodology, Investigation, Writing – Review & Editing; HJL: Methodology, Investigation, Writing – Review, & Editing; SMP: Methodology, Investigation, Writing – Review & Editing; JWSu: Resources, Investigation, Writing – Review & Editing; JYK: Resources, Investigation, Writing – Review & Editing; JWSo: Resources, Investigation, Writing – Original draft; YKY: Conceptualization, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Writing – Original draft, Writing – Review & Editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The study design and methods were approved by the Institutional Review Board of Korea University Anam Hospital (Approval No. 2020AN0208).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sung, Y.H., Ju, Y.K., Lee, H.J. et al. Clinical performance of real-time nanopore metagenomic sequencing for rapid identification of bacterial pathogens in cerebrospinal fluid: a pilot study. Sci Rep 15, 3493 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87858-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87858-z