Abstract

The Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment (GRACE) mission provides original observations to different institutions for the production of various monthly time-variable gravity field models (TVGFMs). Aiming to optimize the signal-to-noise ratio of TVGFMs, we determine to combine them in the spatial domain. This combination comprises two approaches: one combines spherical harmonic coefficient (SHC) solutions, and the other combines SHC and mascon (mass concentration) solutions together. For each approach, we employ four old weighting schemes and one new scheme named oceanic accuracy weighting. We then assessed the combined models through both internal and external validations. In external validation, we compare the Caspian Sea level changes derived from the combined models with those obtained from satellite altimeter. Our results reveal an improvement of the SHC combination using variance component estimation (VCE) weighting compared to any single SHC solution. Moreover, we found enhanced performance in the combined models with the incorporation of mascon solutions, particularly employing the oceanic accuracy weighting. These findings underscore the efficacy of model combination in improving performance, and emphasize the importance of selecting appropriate weighting strategies for integrating GRACE solutions. Specifically, we recommend VCE weighting scheme for combining SHC solutions only and oceanic accuracy weighting scheme for integrating mascon and SHC solutions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment (GRACE) and its successor GRACE Follow-on (GRACE-FO) have revolutionized the observation of Earth’s surface mass changes in a large scale with consistent spatiotemporal resolution1,2,3. The most frequently utilized GRACE/GRACE-FO Level-2 monthly gravity field solutions are typically represented as spherical harmonic coefficients (SHCs), which are regularly provided by three official processing centers within the GRACE/GRACE-FO Science Data System (SDS) (i.e., Center for Space Research at the University of Texas (CSR), Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), and German Research Center for Geosciences (GFZ))4,5,6 and other processing centers (e.g., Astronomical Institute of the University of Bern (AIUB) and Institute of Geodesy at Graz University of Technology (ITSG))7,8. On the other hand, the GRACE/GRACE-FO Level-3 monthly solutions known as mass concentration blocks (mascon)9,10 are also generated by CSR, JPL, and GSFC (Goddard Space Flight Center), which are directly represented as gridded terrestrial water storage (TWS) changes. GRACE/GRACE-FO products find extensive applications across various Earth science disciplines, including geodesy, hydrology, oceanography, atmospheric science, and glaciology11,12,13,14,15,16. Moreover, the precise GRACE/GRACE-FO time-variable gravity field model(TVGFM) is invaluable for enhancing the orbit determination of low-orbit satellites, underscoring the importance of refining existing TVGFMs17.

Before presenting the motivation for our work, it is essential to clarify the limitations and advantages of GRACE/GRACE-FO monthly SHC and mascon solutions. Both can provide vertically integrated mass changes on the Earth’s surface. However, to extract surface mass changes, SHC solutions require complex postprocessing, e.g., Gaussian smoothing18, de-striping19, leakage correction20, and GIA correction21. In contrast, mascon solutions, which do not require postprocessing as the regularization is incorporated into the solving process from Level-1B data to Level-3 solutions, are more user-friendly for non-geodetic users and have extensive applications in the study of hydrological processes. Aside from that, Bhanja et al.22 found that mascon solutions outperform SHC solutions in recovering the trends of groundwater storage anomalies within most of river basins in India. Scanlon et al.23 concluded that mascon solutions perform as well as or even better than SHC solutions in basins larger than 40,000 km2. Although mascon solutions offer many advantages, their high spatiotemporal resolution remains controversial, and existing studies indicate that mascon does not have a definitive advantage over SHC solutions worldwide. In certain basins of small size, mascon fails to detect clear signals while SHC solutions can reveal pronounced geophysical signals. Zhang et al.24 showed that mascon solutions fail to detect the abrupt water level changes in Longyang reservoir and have poorer performance compared to SHC solutions in subregions of Tianshan. They also recommended to carefully use mascon solutions in small basins (< 100,000 km2). Chen et al.25 investigated Caspian Sea level (CSL) changes using multisource data and compared mascon-based and SHC-based CSL changes with those derived from satellite altimetry observations. Their findings indicate that the forward-modeled gridded spherical harmonic products have better correlation with satellite altimetry observations but CSR and JPL mascon solutions are still impacted by leakage errors.

Based on the limitations and advantages of mascon and SHC solutions, we are motivated to combine two forms of GRACE solutions, aiming to generate an ensemble solution that mitigates shortcomings while leveraging the advantages of the participating solutions. Previous studies have also proven the validity of simultaneously combing mascon and SHC solutions. Sakumura et al.26 creatively generated ensemble SHC solution in the spectral domain using multiple monthly gravity field solutions with equal uncertainties from different processing centers, demonstrating effectiveness in reducing noise in individual solutions. Jean et al.27 employed VCE (variance component estimation) in the spectral domain to assign weights to various models for their combination. Moreover, Meyer et al.28,29 combined GRACE monthly gravity field models on the level of normal equation. Yan et al.30 combined GRACE monthly mascon and SHC solutions to thoroughly investigate a drought event in eastern China in 2019. Gao et al.31 quantified the uncertainty of the mascon-derived and SHC-derived TWS changes by using the generalized three-cornered hat method and generated a higher-quality ensemble solution. However, the impact of different weighting strategies on the TWS ensemble solution and whether the performance of final combined solution is influenced by the individual solutions’ shortcomings or advantages have not been thoroughly investigated.

It should be noted that the abovementioned combination methods are based on the combination of different TVGFMs originated from the same GRACE/GRACE-FO Level-1B observations, and there must be a high degree of correlation between the TVGFMs, while the above combination methods do not take into account the correlation of individual models. This does not appear to be mathematically valid. But different agencies exploit different data pre-processing approaches, different background force models, and different parameterization strategies, resulting in different noise patterns in individual models. We therefore consider different TVGFMs to be more or less independent. The above combinations as well as the combinations to be carried out in this manuscript are all based on this assumption. This assumption is also often used for intra-technique combinations within ITRF (International Terrestrial Reference Frame)32. The effect of correlation between models on the combined model is beyond the scope of this manuscript.

We also conducted a close-loop simulation study (Text S1). Through the simulation study, we could validate that the normally distributed random errors could be reduced after combination through VCE strategy even if the strong correlation exists among the individual models, though the systematic errors may not be easily reduced. The conclusions drawn from this simulation match well with the conclusions of the real calculations. We further investigated the characteristic of the differences between the CSR and ITSG SHC solutions (Fig. S2). The results show that most of the differences follow a normal distribution, indicating that the differences are as likely to be eliminated as random errors in the combination.

In this study, we generated various TWS combination solutions using one new and four established weighting schemes on the level of solutions, analyzing the final combinations in terms of noise level and correlation with external observations and demonstrating the impact of different weighting strategies on the final combined solution. To demonstrate the impact of mascon solutions on the combined solutions, we established two control groups: one containing only SHC solutions and the other including both SHC and mascon solutions. Both groups used the same weighting strategy for combination and were assessed with identical criteria to evaluate the noise and signal characteristics of the final combined solutions. To evaluate noise levels, we calculated statistical values of the non-seasonal and non-trend residuals in the open ocean region for each model. This metric also serves as an innovative weighting scheme designed to leverage the advantages of mascon solutions compared to previous methods. Additionally, we assessed both individual and combined solutions in the Caspian Sea. Through this comparison, we aim to determine whether the combination solutions lean toward the shortcomings or advantages of the individual solutions. In other words, we will assess whether the shortcomings in individual solutions can be mitigated by the advantages of others, ultimately resulting in a combination solution with superior global performance.

The article is structured as follows. “Data” section describes the data sets used in this study. In “Materials and methods” section, we show the details of the weighting schemes and the process of constrained forward modeling. In “Results and discussion” section, we apply the internal and external validation to evaluate the performance of the individual and combined models. We estimate the noise level of each model in internal validation. Meanwhile, we assess the quality of each model by comparing the CSL change obtained from TVGFM with those derived from satellite altimetry observations in external validation. “Conclusions” section presents conclusions.

Data

GRACE SHC solutions

This study uses SHC solutions released by five institutions: CSR, JPL, GFZ, AIUB, and ITSG. Due to the discrepancy between the SHCs of AIUB release 2 with 90 degree and the SHCs of other institutions up to degree 96, the study chooses to conduct the experiment using SHCs from each institution within degree 60. Furthermore, the AIUB release 2 spans from March 2003 to March 2014, and the study is conducted within that timeframe. Detailed information about each SHC solution is presented in Table S1.

Each SHC solution undergoes preprocessing, followed by post-processing to convert the SHCs in the spectral domain to equivalent water height (EWH) on grids in the spatial domain. For the preprocessing, on the one hand, the physical parameters need to be standardized, including the gravitational constant and the Earth’s equatorial radius. This standardization involves multiplying each model’s SHCs by a scale factor28. On the other hand, if a model has missing data in a certain month, the corresponding data from other models in the same month is excluded to ensure that each model has the same number of data points. In the post-processing, several steps are undertaken:

-

(1)

The addition of degree 1 terms33 and replacement of C2034 for each SHC solution.

-

(2)

Removal of the mean field for each model from 2004.0 to 2009.999.

-

(3)

Application of a Gaussian filter with a radius of 300 km35. Decorrelation filtering is not applied in this study because excessive smoothing would weaken the signal, making it unfavorable for comparison with mascon solutions19.

-

(4)

GIA (glacial isostatic adjustment) correction21,36 is not considered as its effect is small in the Caspian Sea.

-

(5)

Performance of spherical synthesis to obtain EWH.

Although the true resolution of GRACE is roughly \(3^\circ \times 3^\circ\), the EWH is represented on grids of \(0.5^\circ \times 0.5^\circ\) for convenient comparison and analysis with mascon solutions. During the inversion of the Caspian Sea level change in this study, a constrained forward modeling is applied to recover the signals attenuated by leakage errors, following the approach of Chen et al.25.

GRACE mascon solutions

The mascon products used in this paper include CSR RL06.2 mascon9 and JPL RL06.1 mascon1,10,37. For release 06 of the Level-3 products, both CSR and JPL employ observations and background models of equivalent quality. While CSR RL06.2 mascon introduces enhancements such as refined handling of original observations and constraints over the Arctic Ocean compared to CSR RL06 mascon, overall consistency is maintained between the two versions, and they align with JPL RL06.1 mascon in terms of quality. Notably, we can find mascon products, from CSR and JPL, that do not recover GAD (G: Geopotential coefficients, A: Average of any background model over a time period, D: bottom-pressure over oceans, zero over land) in the oceanic region, which is consistent with the EWH inversed from SHC solutions in the oceanic area. To maintain consistency with the SHC solutions, GIA correction in the mascon solutions have been eliminated in this study. The GSFC mascon solution38,39 restores GAD in the oceanic region but does not provide GAD grid data for correction. In the oceanic region, it does not match the EWH inversed from SHC solutions, so this study does not consider using GSFC’s mascon products. The spatial resolution of CSR mascon (CSR MC) is \(0.25^\circ \times 0.25^\circ\), and it is need to be resampled to \(0.5^\circ \times 0.5^\circ\) in this study. JPL mascon (JPL MC) is released on \(0.5^\circ \times 0.5^\circ\) latitude and longitude grids, but the actual resolution of the product is \(3^\circ \times 3^\circ\). Table S2 shows the detailed information of mascon solutions.

Caspian Sea level change from satellite altimeter

HYDROLARE, supervised by the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) and developed by the Laboratoire d’Etude en Géophysique et Océanographie Spatiale (LEGOS) and the State Hydrological Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences (SHI), is a lake data center that provides time series of water level changes for lakes and reservoirs through the HYDROWEB website. These water level changes for lakes, wetlands, and inland seas are derived from multi-source satellite altimetry data, including satellites such as Topex/Poseidon, Jason-1/2, ENVISAT, ERS-1/2, and GFO40. The time series of water level changes for the Caspian Sea used in this study are obtained from HYDROWEB. The obtained time series for the Caspian Sea level changes are available on a monthly basis from March 2003 to October 2011, with one value per month. However, from November 2011 to March 2014, there are three values per month. In these months, we choose to average the multiple values to obtain one value per month. The Caspian Sea level change obtained through satellite altimetry serves as a reference value to assess the performance of the GRACE solutions.

Hydrology data

NASA(National Aeronautics and Space Administration)'s Global Land Data Assimilation System (GLDAS) is dedicated to utilizing an advanced land surface modeling and data assimilation system to integrate satellite and ground-based observational data products to produce optimal values for land surface states and fluxes41. GLDAS-2, comprising versions 2.0, 2.1, and 2.2, drives three land surface models: Noah, Catchment (CLSM), and VIC. This study utilizes the monthly output of the Noah model from GLDAS-2.1, specifically the GLDAS_NOAH10_M 2.1 dataset, with a spatial resolution of \(1^\circ \times 1^\circ\). The required physical quantity for the study is the soil moisture from 0 to 200 m in the Noah model, which needs to be resampled to \(0.5^\circ \times 0.5^\circ\) resolution. This quantity is used to simulate the hydrological change signal around the Caspian Sea. When using GRACE to recover the Caspian Sea level changes, it’s imperative to remove the influence of the hydrological signal around the Caspian Sea.

Temperature and salinity data

When utilizing the TVGFM to invert the Caspian Sea level changes, it’s crucial to account for steric changes induced by temperature and salinity variations in the Caspian Sea. In this study, the employed temperature and salinity dataset is EN.4.2.2, released by the UK Met Office Hadley Centre42. This dataset integrates data from four sources: Argo, ASBO (Arctic Synoptic Basin-wide Oceanography project), GTSPP (Global Temperature and Salinity Profile Program), and WOD18 (World Ocean Database 2018), which is subjected to quality control and objective analysis. During quality control, duplicate data is eliminated, and corrections are applied for instrument biases present in the data. Instrument biases requiring correction include those of XBT (expendable bathythermograph) and MBT (mechanical bathythermograph). EN.4.2.2 encompasses four distinct datasets, each corresponding to different instrument bias correction schemes. The correction scheme employed for the dataset in this study involves utilizing the method proposed by Cowley et al.43 for correcting XBT instrument errors and the method proposed by Levitus et al.44 for correcting MBT instrument errors. It’s important to note that a mean field from 2004.0 to 2009.999 was removed from steric changes in this study, which is a common processing method used for Caspian Sea level change from satellite altimeter and hydrology data from GLDAS-Noah.

Materials and methods

Weighting scheme

In this study, the combination of TVGFMs were categorized into two groups: one group for combining SHC solutions and the other for combining mascon and SHC solutions. Within these groups, five distinct weighting strategies were employed. Each weighting strategy determined the weight assigned to each model on a monthly basis, aligning with the temporal resolution of GRACE solutions. Following the weighting process, the combined results for each grid point in various months are represented as weighted arithmetic means as follows:

where \(\overline{X}_{\lambda ,\varphi }^{t}\) represents the combined EWH at longitude \(\lambda\), latitude \(\varphi\), and month \(t\). \(X_{\lambda ,\varphi }^{t,i}\) represents the EWH at longitude \(\lambda\), latitude \(\varphi\), and month \(t\) in the \(i\)th model, and \(w_{\lambda ,\varphi }^{t,i}\) represents the corresponding weight of \(X_{\lambda ,\varphi }^{t,i}\) in combination. \(N\) means the number of models. The five weighting strategies are shown in Table 1.

Arithmetic mean

Equal-weight combination represents the simplest and most direct method for combining models. Based on the assumption of uniform accuracy across all models, equal weights are assigned to each model. In practice, this involves calculating the average value of each model at each grid for the corresponding month to derive the combined solution, i.e., \(w_{\lambda ,\varphi }^{t,i} = 1\) in Eq. (1).

Grid-wise weighting

The grid-wise weighting involves subtracting the equal-weight combination result from each model point by point. The reciprocal of the square of the difference serves as the weight for the corresponding grid point. Assuming that the mean values of all models are optimal in every grid point, models that exhibit larger differences with respect to mean values receive smaller weights during combination. This method assigns weights to each grid point, resulting in different weights for different grid points within the same model. The formulation is as follows:

where \(w_{\lambda ,\varphi }^{t,i}\) is the weight corresponding to \(X_{\lambda ,\varphi }^{t,i}\), \(\overline{X}_{\lambda ,\varphi }^{t}\) represents the arithmetic mean value at longitude \(\lambda\), latitude \(\varphi\), and month \(t\) as shown in Eq. (1).

Field-wise weighting

The process of field-wise weighting entails computing the point-to-point difference between individual models and the equal-weight combination. Subsequently, the differences across global regions for each model are summed, serving as the basis for weighting. As only one weight is assigned to each monthly solution using this method, it is referred to as field-wise weighting, which dramatically reduces the number of weights associated with each model. Specific calculation details are outlined in Eq. (3).

As the above equation shows, \(N_{grid}\) represents the total number of grids in the global region. \(\lambda_{\max }\) and \(\lambda_{\min }\) represent the maximum and minimum of longitude. \(\varphi_{\max }\) and \(\varphi_{\min }\) represent the maximum and minimum of latitude. \(w^{t,i}\) represents the weight of the \(i\) th model in the \(t\) th month.

Weighting by VCE

In practical application, the VCE weighting involves recalculating the weights of observations using adjusted residuals, which are then applied to adjust the observation equations45,46,47. Through a finite number of iterations, appropriate observation weights are obtained. Jean et al.27 employed VCE in the spectral domain to assign weights to various models for their combination. In spectral domain combination, the SHCs of each model serve as virtual observations, while the SHCs of the combined model are treated as unknowns to be estimated. In our study, we employed VCE to determine suitable weights for combining various models in the spatial domain. In spatial domain combination, the EWHs on a grid from each model are designated as virtual observations, while the EWHs of the combined model are treated as unknowns to be estimated, forming an observation equation for adjustment. Through a finite number of adjustment iterations and weightings, reasonable weights for each model are determined. For specific details regarding the VCE method, please refer to Text S2.

Oceanic accuracy weighting

Due to the presence of distinct nuisance signals in mascon and SHC solutions, both field-wise and VCE weighting methods encounter challenges in effectively incorporating mascon solutions. Consequently, the benefits of mascon solutions are not adequately integrated into the combined models. To tackle this issue, our study devises a weighting strategy based on the accuracy of each model. Model accuracy is evaluated using the known noise level of each model which has been assessed based on residuals in the oceanic region (Fig. 12). A lower noise level indicates higher model accuracy and is assigned a larger weight, and vice versa. Accordingly, the weight can be calculated as follows:

where \(w^{t,i}\) is the weight for the \(i\)th model at \(t\)th month and \(RMS^{t,i}\) represents the corresponding RMS (Root Mean Square) computed by the residuals in the open ocean.

Internal validation

During the TVGFM inversion process, high-frequency non-tidal mass changes in the atmosphere and ocean are removed using atmospheric and oceanic de-aliasing (AOD) models48. Residual mass change signals over the oceans primarily represent noise, along with true ocean mass changes associated with net water mass exchanged with land. In the study of time-variable gravity field uncertainty by Chen et al.49, barystatic sea level change (BSLC) is considered to be caused by land-sea water mass exchange. Consequently, gravity-induced sea level change can reflect mass changes on land. Under the assumption that the ocean and land have similar noise levels, the assessment of errors in the oceanic region can be utilized to estimate the uncertainty of TWS changes. Thus, the problem of assessing the accuracy of the TVGFM is transformed into estimating the noise level in the ocean. The oceanic noise level can be determined by analyzing the residual after removing the BSLC50, which primarily exists in the form of seasonal and long-term signals. In this study, Eq. (5) is employed to fit and remove seasonal and long-term signals. The remaining residuals, after removing the main signals, are used to calculate the RMS, which serves as an indicator of the TVGFM accuracy.

Here, \(H\) is EWH at latitude \(\varphi\), longitude \(\lambda\), \(\beta_{0}\) represents a bias, \(\beta_{1}\) represents the linear trend, \(\beta_{2}\) is the annual amplitude, and \(\beta_{3}\) is the semi-annual amplitude. The annual and semi-annual variations are collectively referred to as seasonal changes. \(w_{1}\), \(w_{2}\) and \(\varphi_{1}\), \(\varphi_{2}\) represent the annual and semi-annual frequencies and phases, respectively. \(\varepsilon\) is the difference between the fitted value and the observed value, also known as observation residual.

External validation

In the absence of true TWS changes, we decide to introduce Caspian Sea level changes derived from satellite altimetry as reference values to assess the performance of GRACE solutions51. This subsection describes the methods used to invert the CSL changes separately using GRACE SHC and mascon solutions.

Caspian Sea level changes inverted from SHC solutions

When representing the GRACE gravity field as SHCs, truncation errors arise. Additionally, Gaussian filtering is applied during post-processing, further contributing to deviations from true TWS changes. These deviations are referred to as “leakage errors”. Leakage errors can be categorized into external and internal types. In the context of the Caspian Sea, external leakage error occurs when signals from the Caspian Sea propagate outward, resulting in a weakening of the signal within the Caspian Sea itself. On the other hand, internal leakage error involves signals from surrounding areas leaking into the Caspian Sea. While internal leakage has a minimal effect on the signal amplitude, it mainly introduces phase deviations in the signal compared to the true signal. To restore the signal attenuated by external leakage error, this study employs the constrained forward modeling method52. This approach confines the signal within the area of interest, ensuring that signals in surrounding regions remain unaffected, under the condition of the known geography of the Caspian Sea25. To address internal leakage error, hydrological change signals around the Caspian Sea are simulated using the soil water component of the GLDAS-Noah model. Signals simulated within a 200 km radius around the Caspian Sea are then removed from the CSL changes, serving as a correction for internal leakage error. Additionally, variations in water temperature and salinity may induce steric changes in the CSL that are not captured by GRACE. To account for this, steric changes are incorporated into the leakage error-corrected results to obtain the overall CSL changes.

Using the SHC solution from CSR as a case study, we illustrate the entire process of inverting the CSL changes, which will be consistently applied with other SHC solutions. Initially, we address signal attenuation induced by external leakage error through the constrained forward modeling approach. Long-term trends are selected as the focal points for constrained forward modeling. These trends are less susceptible to noise contamination compared to individual monthly data. Therefore, they serve as suitable targets for the constrained forward modeling process52.

Figure 1 depicts the convergence of the trend within the Caspian Sea and the discrepancy between the modeled and observed trends as the number of iterations increases during constrained forward modeling. In Fig. 1a, the initial value of the average trend within the Caspian Sea stands at − 2.7 cm/a. As iterations progress, the trend gradually converges, reaching an approximate value of − 6.7 cm/a upon convergence of the constrained forward modeling process. We assume that seasonal and longer time-scale variations in GRACE estimates are subject to the same leakage bias ratio as trend (2.7/6.7). Thus, we adjust the GRACE CSL change by the reciprocal (6.7/2.7) to eliminate external leakage bias. Figure 2 showcases the spatial distribution of the trend of CSL change before and after constrained forward modeling. In Fig. 2a, the spatial distribution of the long-term trend of CSL change before modeling is presented. Due to leakage errors, the signal is dispersed both within and outside the Caspian Sea, with signal intensity weaker by an order of magnitude compared to signals shown in Fig. 2b. This comparison demonstrates that the constrained forward modeling effectively confines and restores the signal content within the area of interest.

Using the data of January 2005 as a reference, Fig. 3 illustrates the spatial distribution of soil water storages around the Caspian Sea and steric changes in the CSL. In Fig. 3a, the spatial distribution of four-layer soil water extracted from the GLDAS-2.1 Noah model is presented, representing the hydrological signals surrounding the Caspian Sea. It is assumed that these surrounding soil water signals may leak into the Caspian Sea region during the post-processing stage, leading to biases in the inversion results of CSL changes. The hydrological signal’s magnitude is substantial, exerting a remarkable impact on the inversion of CSL changes. Figure 3b displays the spatial distribution of steric changes in the CSL calculated from EN.4.2.2 temperature and salinity data. Here, the magnitude of steric changes in the CSL is small, resulting in a minor impact on the inversion results of CSL changes. However, these steric changes are beneficial for refining the phase of CSL changes.

The CSL changes derived from different processing methods using GRACE data are analyzed to extract annual variations and linear trends using unweighted least squares. These results are then compared with observations from satellite altimetry (Table 2). The satellite altimeter observations reveal the CSL change with an annual amplitude of 17.67 cm, a semi-annual amplitude of 3.3 cm, and a linear trend of − 6.32 cm/a. In Table 2, the GRACE-derived CSL changes are obtained from SHC solutions provided by CSR, employing different processing strategies. Among these strategies, the strategy CSR SH (300 km + FM + Steric-SWS) exhibits the closest agreement with the satellite altimetry results. This strategy involves applying a 300-km Gaussian filtering, constrained forward modeling (FM) to recover the signal, subtracting soil water storage (SWS) around the Caspian Sea, and restoring steric changes in the CSL (Steric). The resulting CSL changes show an annual amplitude of 16.88 cm, an annual phase of 180.59°, a semi-annual amplitude of 3.36 cm, a semi-annual phase of 347.77°, and a trend of − 6.14 cm/a. Performance evaluation metrics provided in Table 3 further support the effectiveness of this strategy, indicating the highest correlation with satellite altimetry results.

Figure 4 also demonstrates that incorporating internal leakage corrections and steric changes leads to CSL changes derived from GRACE SHC solutions that are more aligned with those obtained from satellite altimetry. This alignment is notably improved compared to CSL changes derived solely from GRACE SHC solutions without accounting for internal leakage errors or steric changes in the CSL. These results emphasize the importance of considering hydrological signals around the Caspian Sea and steric changes when calculating CSL changes using GRACE SHC solutions.

In this study, we assess the quality of each model by comparing the CSL changes obtained from satellite altimetry (considered as reference values) with those derived from the GRACE TVGFM (considered as model values). To conduct a comprehensive analysis of the TVGFM quality and to facilitate comparison with external data, we utilize evaluation metrics such as the Pearson correlation coefficient (R), normalized root-mean-square error (NRMSE) and Nash–Sutcliffe efficiency (NSE)53,54. The R measures the linear correlation between model values and reference values, with a value closer to one indicating a higher correlation. NRMSE quantifies the residual variance between model values and reference values, with a lower value indicating better model performance. NSE assesses the relative magnitude of signal and noise, with a value closer to one indicating better model performance55. For further details on these evaluation metrics, please refer to Text S3.

The evaluation of different processing methods for CSL change is conducted by comparing them with satellite altimeter observations (Table 3). The comparison between the CSR SH (300 km + FM) and CSR SH (300 km + FM + Steric) strategies reveals the necessity of considering steric changes in the CSL when using GRACE TVGFM to calculate the CSL change. This refinement results in a closer approximation to the CSL changes obtained by satellite altimetry, with an increase in R by 0.023, an increase in NSE by 0.047, and a decrease in NRMSE by 0.017. Furthermore, comparing CSR SH (300 km + FM + Steric) with CSR SH (300 km + FM + Steric-SWS) strategies indicates that considering internal leakage error due to hydrological signals around the Caspian Sea further improves the inversion results, bringing them into closer alignment with satellite altimetry observations. The strategy (300 km + FM + Steric-SWS) is extended to other SHC solutions such as JPL SH, AIUB SH, GFZ SH, and ITSG SH.

Caspian Sea level changes inverted from mascon solutions

During the inversion process of GRACE mascon solutions, different institutions have employed various methods to correct leakage errors. For instance, the JPL MC solution utilizes a coastline resolution improvement filter to mitigate leakage errors from both the ocean and land37. On the other hand, the CSR MC solution corrects leakage errors using a regularization matrix, solely relying on GRACE information without external models. However, the Caspian Sea, being an inland sea, is not explicitly considered in mascon solutions when correcting the land–ocean leakage error. Consequently, leakage errors persist in the Caspian Sea region in mascon solutions. Figure 5 illustrates the trends in the Caspian Sea, revealing a notable signal present around the Caspian Sea. However, given that the Caspian Sea is situated in an arid region, significant hydrological signals should not be observed in its vicinity. This suggests that the existing signal around the Caspian Sea is likely caused by leakage from the Caspian Sea, indicating that leakage errors persist in mascon solutions in this region.

When inverting the CSL using mascon solutions, it’s crucial to address leakage errors. Therefore, we adopt the same method as Chen et al.25 to invert the CSL changes using mascon solutions. In this process, we expand the boundary of the Caspian Sea outward by 200 km, as signals in mascon solutions are not entirely confined within the Caspian Sea (Fig. 5). We consider that the signal within 200 km outside the Caspian Sea is part of the Caspian Sea region signal. Additionally, considering the slight hydrological signals around the Caspian Sea, we utilize the four-layer soil moisture component in the Noah model to simulate these hydrological signals, as depicted in Fig. 3a. By removing this hydrological signal from the mascon solutions, the remaining signals around the Caspian Sea are attributed to leakage from the Caspian Sea, which should be incorporated into CSL changes. This step is called as leakage correction (LC). Additionally, the steric changes induced by salinity and temperature should also be considered when estimating the CSL changes by using the gravity observation (Fig. 6).

Results and discussion

Weighting results

The weighting results of the four weighting strategies, i.e., grid-wise weighting, field-wise weighting, VCE, and oceanic accuracy weighting, are shown in the following figures. Figure 7 illustrates the spatial distribution of weights assigned to various TVGFMs when combining SHC solutions without incorporating mascon solutions using grid-wise weighting. Each model’s weight indicates its proximity to the average value, with higher weights assigned to models exhibiting smaller deviations from the average. This closeness to the average can be interpreted as proximity to the “truth”, assuming the average approximates the true value. Adjusting the weights of each model based on its deviation from the average value is therefore reasonable. The spatial distribution of weights in Fig. 7 corresponds to the RMS values shown in Fig. 12. The RMS distribution of SHC solutions reveals that ITSG SH and CSR SH exhibit relatively lower RMS compared to other SHC solutions. Consequently, ITSG SH and CSR SH receive higher weights, while JPL SH, GFZ SH, and AIUB SH are assigned smaller weights, reflecting their larger RMS values. Characterized by smaller RMS values, models assigned higher weights are deemed closer to the true values and therefore have higher accuracy. This result suggests that the residuals obtained after removing seasonal and long-term signals partially reflect the accuracy of the models.

Spatial distribution of normalized weights (dividing the weights of each model by the sum of weights of all models in combination grid by grid) for each model in the combination of SHC solutions using grid-wise weighting. (a–e) represent weights corresponding to the GRACE SHC solutions of AIUB, CSR, GFZ, ITSG, and JPL. For ease of visualization and comparison, the weights corresponding to individual models were averaged over time from March 2003 to March 2014.

The analysis also reveals regional variations in weights for individual models, with some regions exhibiting higher weights and others lower weights compared to the overall weight level. To provide a more detailed examination, we delve into the grid-wise weights of each model from a global scale down to the Antarctic region (Fig. S3). Generally, ITSG SH and CSR SH possess high weights, but in the Weddell Sea region east of the Antarctic Peninsula, ITSG SH demonstrates higher weights, while CSR SH displays lower weights compared to the surrounding areas. Similarly, JPL SH and GFZ SH exhibit weight variations in the Weddell Sea compared to their surrounding regions. These findings suggest that, although certain models generally approximate the “true” value, there are notable deficiencies in local areas within these models. However, this deficiency can potentially be mitigated through model combination. The advantage of model combination becomes evident as the adjustment of weights for each model during the combination process enables the integration of more accurate components while reducing the influence of parts deviating from the true value. This underscores the potential of model combination to enhance overall accuracy by leveraging the strengths of individual models in different regions.

Figure 8 illustrates the spatial distribution of weights for the combination of SHC and mascon solutions. Notably, the weight distribution of CSR MC exhibits more pronounced regional differences. In this distribution, most regions in Asia, north Africa, and certain oceanic areas demonstrate higher weights, whereas regions in the western Antarctic, Antarctic Peninsula, and Greenland exhibit notably lower weights. Upon analyzing the RMS values of CSR mascon solutions from Fig. 12, a correlation emerges: regions with higher weights in CSR mascon solutions correspond to smaller RMS values, whereas regions with lower weights correspond to larger RMS values. RMS retains non-seasonal and non-trend signals as a statistical metric calculated using residuals after removing seasonal and linear trend signals. A larger RMS value indicates a higher proportion of non-seasonal and non-trend signals within the model. Consequently, as the proportion of these signals increases within each model, the corresponding weights decrease. This observation suggests that the true mass change signal tends to comprise seasonal and linear trend signals under the assumption that there are no apparent other mass change signals in the true signal.

The spatial distribution of normalized weights for each model in the combination of SHC and mascon solutions using grid-wise weighting, averaged from March 2003 to March 2014. (a–e) represent weights of GRACE SHC solutions of AIUB, CSR, GFZ, ITSG, and JPL. (f–g) represent weights of mascon solutions of CSR and JPL.

In the combination of SHC solutions with field-wise weighting, ITSG SH and CSR SH exhibit relatively higher weights, followed by JPL SH, GFZ SH, and AIUB SH (Fig. 9a). Notably, since April 2011, the thermal control system was turned off to prevent degradation of GRACE batteries, leading to environmental temperature fluctuations affecting the accelerometers’ normal operation56. Consequently, more substantial noise is introduced into the inverted SHC solutions. Analyzing the weight distribution of each model reveals that AIUB SH is particularly affected by changes in satellite equipment compared to other models, as its weight notably decreases from April 2011 onwards. Similarly, other models also experience effects from these equipment changes, resulting in a more similar distribution of weights of all models. This effect becomes more pronounced when mascon solutions are included (Fig. 9b). Despite the addition of mascon solutions, the relative size of weights among SHC solutions remains unchanged. However, between January 2013 and March 2014, the weights tend to become more consistent. Furthermore, it is evident that the weights of mascon solutions are smaller than those of any SHC solutions. This discrepancy suggests significant differences in the inversion methods between mascon and SHC solutions, resulting in variations in both noise and signal strength contained in the two forms of GRACE solutions. Given that the number of SHC solutions used in the combination exceeds the number of mascon solutions, the calculated average of all models tends to be numerically biased toward SHC solutions. Consequently, this numerical bias increases the disparity between mascon solutions and the average, leading to smaller weights assigned to mascon solutions.

Figure S4 illustrates the field-wise weights for each model when an equal number of SHC (i.e., AIUB SH and GFZ SH) and mascon solutions (i.e., CSR MC and JPL MC) are combined. Notably, when the number of SHC solutions decreases, the weight of mascon solutions increases. However, the relative size of weight between mascon and SHC solutions remains unchanged. These findings suggest that mascon solutions are perceived to deviate more from the “true” value and are consequently assigned a lower weight. One possible explanation for this phenomenon is that mascon solutions employ regularization during the gravity field inversion process, which has a stronger smoothing effect compared to the 300 km Gaussian filter used in conventional SHC solutions. As a result, the EWH value of mascon solutions may be smaller than that of conventional SHC solutions, leading to their lower weight allocation.

The weights obtained by VCE (Fig. 10) align with the field-wise weighting results. Specifically, ITSG SH and CSR SH exhibit relatively higher weights, whereas JPL SH, GFZ SH, and AIUB SH demonstrate relatively lower weights. Moreover, VCE-based weighting amplifies the discrepancies in weights among models compared to field-wise weighting. Notably, the weights of ITSG SH and CSR SH are reinforced, while those of other models are further diminished. Concerning the mascon solutions, it is observed that the weights of CSR MC and JPL MC are lower than those of any SHC solutions, potentially obscuring the advantages of mascon solutions. These findings indicate that neither field-wise nor VCE-based weighting adequately assign high weights to mascon solutions, despite their low noise levels. To address this issue, we introduce a new weighting scheme, i.e., the aforementioned oceanic accuracy weighting.

Figure 11 illustrates the weighting outcomes based on oceanic accuracy of each model. For the combination of SHC solutions, the weight distribution aligns with the results obtained from field-wise and VCE weighting. Specifically, ITSG SH and CSR SH exhibit higher weights compared to JPL SH, GFZ SH, and AIUB SH. However, in the combination of SHC and mascon solutions, the weight distribution diverges from the outcomes of field-wise and VCE weighting. Notably, the weights assigned to the two mascon solutions, namely CSR MC and JPL MC, surpass those of any SHC solutions. These elevated weights suggest that the mascon solutions with low noise levels capitalize on advantages in combination. Through oceanic accuracy weighting, we observed that the weights are inversely proportional to the noise levels of the models, which appears reasonable. Subsequent validation is required to ascertain whether assigning higher weights to mascon solutions is justified and contributes to enhancing the performance of the combined model.

Internal validation

In order to achieve gravity field models that preserve the original signals while minimizing random errors, we combine various TVGFMs using different weighting schemes. To assess whether the combination results meet our expectations, it is essential to conduct validations to evaluate the performance of the individual and combined models. To that end, we perform internal validation in this section. More specifically, we evaluate the accuracies of the models by calculating the RMS of residuals in the oceanic areas.

Accuracy of individual models

The global distribution of RMS values for both SHC and mascon solutions exhibits distinct patterns, indicating varying noise levels across different regions (Fig. 12). Analysis of the RMS of SHC solutions reveals several key findings. Regions with notably high noise levels include Greenland’s southwest, the Amazon basin, southeastern South America, the northern part of Sumatra, the Antarctic ice sheet, and the southeastern part of Africa. These areas exhibit apparent non-seasonal and non-trend signals after removing seasonal and long-term trend signals, contributing to elevated RMS values. Clear noise patterns in the north–south direction are evident, with higher noise levels observed in mid to low latitudes compared to high latitudes. This phenomenon may be attributed to the single north–south observation direction of gravity satellites, higher observation coverage in high latitudes, and limited effectiveness of the 300-km Gaussian filtering applied in this study in suppressing striping noise. Comparison of the RMS values among the five SHC solutions indicates that under the same post-processing conditions, CSR and ITSG exhibit markedly lower noise levels compared to AIUB, GFZ, and JPL. This suggests that the strategies employed by CSR and ITSG in handling noise during the inversion of the time-variable gravity field may be more optimal.

The spatial distribution of RMS values from mascon solutions reveals a notable similarity between CSR and JPL solutions, in contrast to the significant disparities observed among various SHC solutions. CSR and JPL mascon solutions demonstrate effective regularization strategies, evidenced by the minimal presence of north–south striping and leakage errors. Consequently, the RMS values in the oceanic region are relatively low, contrasting with higher RMS values observed in terrestrial regions, likely due to the strong hydrology signals present in lands within mascon solutions. These discrepancies between SHC and mascon solutions underscore the necessity of considering their respective characteristics and performance when conducting model combination, as they will influence the weights assigned to each solution.

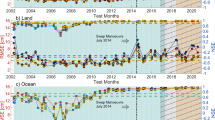

In the analysis, residuals in the oceanic region underwent latitude-weighted averaging each month to derive the weighted RMS time series, offering insights into the noise levels of each model spanning from March 2003 to March 2014, as depicted in Fig. 13. To mitigate the impact of land-sea leakage errors, the coastline was expanded 500 km seaward to encompass open ocean areas. The results revealed that CSR mascon solutions exhibit the lowest noise level among all models. Among the SHC solutions, ITSG SH demonstrates the lowest noise level, followed by CSR SH, JPL SH, GFZ SH, and AIUB SH, respectively.

Combination models from only SHC solutions

In this subsection, we present the accuracies of combined models derived from SHC solutions using five weighting schemes. We visualize the spatial distribution of residual EWH variability on a global scale for each combined model (Fig. 14). Across both oceans and continents, the RMS distribution of the five combined models generally remains consistent. Notably, over continents, the variability attributed to non-seasonal and non-trend mass change signal is retained, contributing to significant RMS values in specific basins such as the Amazon basin, western Antarctica, Greenland, and Sumatra. Conversely, over oceans, where minimal hydrological signal is anticipated, the residuals provide insight into the noise level of each model.

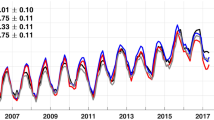

We calculate the global ocean RMS using the residual EWH variability in the oceanic region, as depicted in Fig. 15. It indicates that the CMB VCE model exhibits the lowest noise level, potentially attributed to the VCE method’s ability to determine model weights effectively and subsequently suppress noise more efficiently. Additionally, the mean of the RMS time series for each model is computed and displayed in the legend of Fig. 15. Comparing with the mean RMS of individual SHC solutions in Fig. 13, the performance of the combined models shows a significant improvement. Among the five combined models, both the CMB arithmetic and CMB grid models perform slightly less effectively than the ITSG SH. Conversely, both the CMB accuracy and CMB field models demonstrate equivalent accuracy to the ITSG SH model, while the CMB VCE model surpasses any individual model. Therefore, it can be inferred that the best-performing combined model is the CMB VCE, with a noise level reduction of 5% compared to ITSG SH and 14% compared to CMB arithmetic. These results suggest that directly combining TVGFMs in the spatial domain can effectively mitigate noise. Furthermore, VCE has shown superiority over other weighting strategies in combining SHC solutions, consistent with previous research findings in spectral combination27,29.

Combination models from mascon and SHC solutions

The objective of this subsection is to determine whether the integration of mascon solutions has a beneficial effect on the combined model. Furthermore, we aim to assess whether the performance of combined models under various weighting schemes is altered by their inclusion. From Fig. 16, it is evident that the RMS spatial distribution of the combined model CMB accuracy has undergone significant changes compared to Fig. 14d. This is attributable to the characteristics of the weighting scheme used by the CMB accuracy model, where mascon solutions are assigned larger weights during the combination process. Consequently, the RMS spatial distribution of the CMB accuracy model exhibits characteristics inclined towards mascon solutions. The primary features include the overall absence of clear north–south stripes and a notable reduction of sea-land signal leakage. Furthermore, the RMS in the oceanic region remains at a lower level. However, the RMS in the western Antarctic, Greenland, and other land regions has significantly increased compared to the case without the inclusion of mascon.

From the RMS time series in Fig. 17, it is evident that the inclusion of mascon solutions during the combination process leads to a reduction in the noise levels of the five combined models. Compared to the case where mascon solutions are not included in the combination (Fig. 15), the noise levels of the CMB arithmetic, CMB field, CMB grid, CMB accuracy, and CMB VCE models in Fig. 17 have been reduced by 24%, 5%, 25%, 37%, and 6%, respectively. This indicates that the inclusion of mascon solutions during the combination process can enhance the performance of the combined model, rather than reducing its accuracy. At the same time, we can observe that the noise level of the CMB accuracy model is the lowest among the five combined models. It indicates that the new weighting scheme, based on model accuracy, has more advantages in the combination of mascon and SHC solutions. The reason why previous weighting schemes could not demonstrate superiority in the combination of mascon and SHC solutions is that they overlook the inherent advantages of mascon solutions. So previous weighting schemes fail to assign sufficiently high weights to mascon solutions, which results in mascon solutions contributing too little to the combined model, and we can see that the combined model’s characteristics tend to be more biased towards SHC solutions. The new weighting strategy proposed in this study can overcome the shortcomings of previous weighting strategies and allow the combined model to further improve its performance by incorporating the advantages of mascon solutions.

Although the accuracy of the CMB accuracy model has surpassed that of most individual models shown in Fig. 13, it still falls short of CSR mascon. This could be attributed to the regularization method used in mascon solutions, which may excessively suppress non-seasonal and non-trend signals in the ocean region. Consequently, the residuals are minimal after extracting seasonal and long-term trend signals. When assessing model accuracy by calculating the RMS of residuals, mascon solutions achieve higher accuracy compared to SHC solutions. On the other hand, smoothing SHC solutions using a 300-km Gaussian filtering results in weaker suppression of non-seasonal and non-long-term trend signals compared to regularization methods. Assessing the noise level of SHC solutions using the same method may lead to a higher noise level, thus showing a significant difference in noise levels between mascon and SHC solutions. Therefore, from the view of noise reduction, it is this substantial difference between models that prevents the combined model from surpassing the optimal mascon (CSR MC) despite outperforming most of the models. However, the mass change signal of the combined model maybe closer to the true signal, which will be evaluated with external validation in the following section.

External validation for individual and combined models

Caspian Sea level changes inverted from GRACE solutions

The inverted CSL changes from various SHC solutions are depicted in Fig. 18a–f. It is observed that the ITSG SH and CSR SH models exhibit the best inversion performance, closely aligning with satellite altimetry observations. Although the overall trend of CSL changes from the GFZ SH, JPL SH, and AIUB SH models is consistent with satellite altimetry results, more noise is evident in the details. The evaluation metrics in Table 4 also indicate that CSR SH performs the best, followed by ITSG SH. JPL SH and AIUB SH are at a similar level, while the inversion results of GFZ SH are the poorest. Compared to GFZ SH, CSR SH’s R and NSE increase by 0.018 and 0.041 respectively, and NRMSE decrease by 0.023.

Figure 18g–h presents the outcomes of inverting the CSL changes using CSR MC and JPL MC. The results indicate that when considering the leakage errors in the Caspian Sea of the mascon solution, the inverted CSL changes align closely with the satellite altimetry results, suggesting the feasibility of this inversion strategy. Subsequently, the corrected mascon models are combined with SHC solutions to assess whether the performance of the combined model can be further enhanced compared to the combined model from only SHC solutions. Upon examination of Table 4, it is evident that CSR SH surpasses CSR MC in terms of R, NSE, and NRMSE. Additionally, CSR SH exhibits superior performance compared to JPL MC in terms of NSE and NRMSE. These findings imply that when inverting the CSL change, the SHC solutions may offer superior performance compared to the mascon solutions, aligning with the conclusions drawn by Chen et al.25.

Performance evaluation of combined models

Evaluation for combined models from only SHC solutions

Figure 19 illustrates the degree of agreement between the inverted CSL changes obtained by various combination models and the satellite altimetry data. Notably, we observe that the combination models using different weighting schemes yield similar outcomes. However, in comparison to the results from individual TVGFM depicted in Fig. 18, the combined models demonstrate greater consistency with the satellite altimetry data.

From the results presented in Table 5, it is evident that all combined models outperform the individual models listed in Table 4 across various metrics such as R, NSE, and NRMSE. This indicates that through the combination of individual models, we are able to obtain models of higher quality by employing five different weighting schemes. What is particularly noteworthy is the considerable improvement observed in the CMB VCE model among the five combined models derived from SHC solutions. In comparison to CSR SH, the CMB VCE model demonstrates increases in both R and NSE by 0.003 and 0.004, respectively, while also exhibiting a decrease in NRMSE by 0.003. Additionally, from Fig. 15, it is apparent that the accuracy of the CMB VCE model surpasses that of the other combined models. Taking into account both external and internal validation results, we advocate for the adoption of VCE as the preferred weighting scheme when combining the SHC solutions.

Evaluation for combined models from SHC and mascon solutions

The combination of mascon and SHC solutions using five weighting strategies allows for the assessment of the resulting combination models against satellite altimetry data. Figure 20 illustrates that the inversion results obtained from the CMB accuracy model demonstrate the highest level of agreement with satellite altimetry observations.

Table 6 provides a quantitative evaluation of the combination models from SHC and mascon solutions in terms of three metrics. Among the five combination models, the CMB accuracy model stands out as the best performer, achieving an R value of 0.989, an NSE of 0.976, and an NRMSE of 0.037. Moreover, when compared to mascon solutions in Table 4, the CMB accuracy model shows a 0.001 increase in R compared to JPL MC, along with a notable 0.007 increase in NSE and a 0.005 decrease in NRMSE compared to CSR SH. These results confirm that the combined model offers advantages over individual solutions, indicating an overall improvement in model performance following the combination process.

The optimal combination model for SHC solutions alone is identified as CMB VCE, with performance metrics of R, NSE, and NRMSE at 0.987, 0.973, and 0.039, respectively. However, when incorporating mascon solutions into the combination, the superior model emerges as CMB accuracy. Comparing these optimal combination models in two combination categories, CMB accuracy shown in Table 6 surpasses CMB VCE shown in Table 5 in all three metrics. This improvement underscores the enhanced performance achieved by including mascon solutions in the combination process. Notably, the shift in optimal weighting strategy from VCE to accuracy-based weighting in the combination of mascon and SHC solutions signifies a refinement in the integration of mascon advantages. The superior performance of the CMB accuracy model suggests that accuracy-based weighting better leverages the strengths of mascon solutions, resulting in further enhancements in overall model performance.

Conclusions

By combining SHC-based and mascon-based TWS in spatial domain, we generated TWS ensemble solutions based on five different weighting schemes, where four weighting schemes are designed in consideration of the solution difference and an innovative weighting scheme constructed according to the open ocean residual in each solution. To demonstrate the impact of mascon solutions on the combined solutions, we established two control groups: one containing only SHC solutions and the other including both SHC and mascon solutions. Both groups used the same weighting strategies for combination and were assessed in two study cases. In one case, we calculated the statistical value of open ocean residual to evaluate the noise level of combined and individual solutions. For another, we calculated the correlation with satellite altimetry-inferred CSL changes for each GRACE solution, which is considered as a reasonable validation.

In the results of the noise level evaluation, the group with only SHC solutions demonstrates that the combined solutions obtained using different weighting strategies exhibit noise levels nearly identical to those of ITSG SH with RMS value of 19 mm. However, the combined solutions show a significant improvement compared to other SHC solutions, indicating that the combined solution can absorb the advantageous aspects of the participating solutions. Additionally, although the CMB VCE improved by 1–3 mm in terms of RMS value compared to other combinations, no significant differences were observed between the different weighting strategies, which means the impact of different weighting schemes on combined solutions is minimum in this context. For the group with mascon and SHC solutions, we could observe that the combined solution CMB accuracy (RMS value of 12 mm) improved in noise reduction due to the mascon solutions with lower noise participated in the combination. This phenomenon further proves the conclusions that combined solutions can absorb good performance in the individual solutions. Moreover, it has been shown that the impact of different weighting schemes on combined solutions became more noticeable after mascon solutions participate in combination and a reasonable weighting scheme (e.g., oceanic accuracy weighting) can better combine GRACE solutions.

In comparing satellite altimetry-derived CSL changes, the results indicate that the correlation between CSL changes from the two geodetic techniques (i.e., satellite altimetry and gravimetry) improved following the integration of GRACE solutions in both groups with or without mascon solutions. In the group without mascon solutions, the combined solution CMB VCE outperformed all other combined solutions, achieving an R value of 0.987, an NSE of 0.983, and an NRMSE of 0.039. On the other hand, CMB accuracy in group with mascon solution showed highest correlation with satellite altimetry observation among all combined solutions, with R of 0.988, NSE of 0.976, and the NRMSE of 0.037. The combined solutions using different weighting schemes demonstrated the equal or better performance with the superior individual solution, providing evidence for the validity of combining GRACE solutions.

GRACE-derived TWS is essential for understanding hydrological processes and climate change, and combining TWS from different GRACE solutions is an effective method for enhancing TWS products. Building on previous studies, this work further validates the effectiveness of combining GRACE solutions and enhances our understanding of the noise level and signal retention of the combined solutions. In the Caspian Sea, where mascon and SHC solutions are regarded as differing in quality, we confirmed that the signal is not biased but is refined by the advantages of the participating solutions after combination. However, validating the global performance of combined solutions based solely on the Caspian Sea is insufficient. Therefore, future work should focus on investigating signal characteristics in various basins of different sizes and climate conditions. Moreover, the correlation between models derived from the same observations at the time of model combination deserves to be considered in the future.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

References

Landerer, F. W. et al. Extending the global mass change data record: GRACE follow-on instrument and science data performance. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2020GL088306 (2020).

Tapley, B. D., Bettadpur, S., Watkins, M. & Reigber, C. The gravity recovery and climate experiment: Mission overview and early results. Geophys. Res. Lett. 31, L09607 (2004).

Tapley, B. D. et al. Contributions of GRACE to understanding climate change. Nat. Clim. Change 9, 358–369 (2019).

Bettadpur, S. Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment Level-2 Gravity Field Product User Handbook (Center for Space Research at The University of Texas at Austin, 2018).

Dahle, C. et al. The GFZ GRACE RL06 monthly gravity field time series: Processing details and quality assessment. Remote Sens. 11, 2116 (2019).

Yuan, D. JPL Level-2 Processing Standards Document for Level-2 Product Release 06 (Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, 2018).

Kvas, A. et al. ITSG-Grace2018: Overview and evaluation of a new GRACE-only gravity field time series. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 124, 9332–9344 (2019).

Meyer, U., Jäggi, A., Jean, Y. & Beutler, G. AIUB-RL02: An improved time series of monthly gravity fields from GRACE data. Geophys. J. Int. 205, 1196–1207 (2016).

Save, H., Bettadpur, S. & Tapley, B. D. High-resolution CSR GRACE RL05 mascons. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 121, 7547–7569 (2016).

Watkins, M. M., Wiese, D. N., Yuan, D. N., Boening, C. & Landerer, F. W. Improved methods for observing Earth’s time variable mass distribution with GRACE using spherical cap mascons. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 120, 2648–2671 (2015).

Chambers, D. P. & Bonin, J. A. Evaluation of Release-05 GRACE time-variable gravity coefficients over the ocean. Ocean Sci. 8, 859–868 (2012).

Chen, J. et al. Quantification of ocean mass change using gravity recovery and climate experiment, satellite altimeter, and Argo floats observations. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 123, 10–212 (2018).

Loomis, B. D., Felikson, D., Sabaka, T. J. & Medley, B. High-spatial-resolution mass rates from GRACE and GRACE-FO: Global and ice sheet analyses. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 126, e2021JB023024 (2021).

Wang, J. et al. Recent global decline in endorheic basin water storages. Nat. Geosci. 11, 926–932 (2018).

Groh, A. et al. Evaluating GRACE mass change time series for the Antarctic and Greenland ice sheet—Methods and results. Geosciences 9, 415 (2019).

Luthcke, S. B. et al. Antarctica, Greenland and Gulf of Alaska land-ice evolution from an iterated GRACE global mascon solution. J. Glaciol. 59, 613–631 (2013).

Peter, H., Meyer, U., Lasser, M. & Jäggi, A. COST-G gravity field models for precise orbit determination of low earth orbiting satellites. Adv. Space Res. 69, 4155–4168 (2022).

Wahr, J., Molenaar, M. & Bryan, F. Time variability of the Earth’s gravity field: Hydrological and oceanic effects and their possible detection using GRACE. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 103, 30205–30229 (1998).

Swenson, S. & Wahr, J. Post-processing removal of correlated errors in GRACE data. Geophys. Res. Lett. 33, L08402 (2006).

Landerer, F. W. & Swenson, S. C. Accuracy of scaled GRACE terrestrial water storage estimates. Water Resour. Res. 48, W04531 (2012).

Peltier, W. R., Argus, D. & Drummond, R. Space geodesy constrains ice age terminal deglaciation: The global ICE-6G_C (VM5a) model. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 120, 450–487 (2015).

Bhanja, S. N., Mukherjee, A., Saha, D., Velicogna, I. & Famiglietti, J. S. Validation of GRACE based groundwater storage anomaly using in-situ groundwater level measurements in India. J. Hydrol. 543, 729–738 (2016).

Scanlon, B. R. et al. Global evaluation of new GRACE mascon products for hydrologic applications. Water Resour. Res. 52, 9412–9429 (2016).

Zhang, L. et al. Evaluation of GRACE mascon solutions for small spatial scales and localized mass sources. Geophys. J. Int. 218, 1307–1321 (2019).

Chen, J. L., Wilson, C. R., Tapley, B. D., Save, H. & Cretaux, J. F. Long-term and seasonal Caspian Sea level change from satellite gravity and altimeter measurements. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 122, 2274–2290 (2017).

Sakumura, C., Bettadpur, S. & Bruinsma, S. Ensemble prediction and intercomparison analysis of GRACE time-variable gravity field models. Geophys. Res. Lett. 41, 1389–1397 (2014).

Jean, Y., Meyer, U. & Jäggi, A. Combination of GRACE monthly gravity field solutions from different processing strategies. J. Geod. 92, 1313–1328 (2018).

Meyer, U. et al. Combination of GRACE monthly gravity fields on the normal equation level. J. Geod. 93, 1645–1658 (2019).

Meyer, U. et al. Combined monthly GRACE-FO gravity fields for a global gravity-based groundwater product. Geophys. J. Int. 236, 456–469 (2023).

Yan, X. et al. GRACE and land surface models reveal severe drought in eastern China in 2019. J. Hydrol. 601, 126640 (2021).

Gao, S., Hao, W., Fan, Y., Li, F. & Wang, J. A multi-source GRACE fusion solution via uncertainty quantification of GRACE-derived terrestrial water storage (TWS) change. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 128, e2023JB026908 (2023).

Kutterer, H., Krügel, M., & Tesmer, V. Towards an improved assessment of the quality of terrestrial reference frames. In Geodetic Reference Frames: IAG Symposium Munich, Germany, 9–14 October 2006) (Springer, 2009).

Sun, Y., Riva, R. & Ditmar, P. Optimizing estimates of annual variations and trends in geocenter motion and J2 from a combination of GRACE data and geophysical models. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 121, 8352–8370 (2016).

Loomis, B. D., Rachlin, K. E., Wiese, D. N., Landerer, F. W. & Luthcke, S. B. Replacing GRACE/GRACE-FO C30 with satellite laser ranging: Impacts on Antarctic Ice Sheet Mass Change. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2019GL085488 (2020).

Han, S.-C. et al. Non-isotropic filtering of GRACE temporal gravity for geophysical signal enhancement. Geophys. J. Int. 163, 18–25 (2005).

RichardPeltier, W., Argus, D. F. & Drummond, R. An Assessment of the ICE-6G_C (VM5a) glacial isostatic adjustment model” by Purcell et al. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 123, 2019–2028 (2018).

Wiese, D. N., Landerer, F. W. & Watkins, M. M. Quantifying and reducing leakage errors in the JPL RL05M GRACE mascon solution. Water Resour. Res. 52, 7490–7502 (2016).

Loomis, B. D., Luthcke, S. B. & Sabaka, T. J. Regularization and error characterization of GRACE mascons. J. Geod. 93, 1381–1398 (2019).

Han, S. C., Riva, R., Sauber, J. & Okal, E. Source parameter inversion for recent great earthquakes from a decade-long observation of global gravity fields. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 118, 1240–1267 (2013).

Cr E Taux, J. F. et al. SOLS: A lake database to monitor in the Near Real Time water level and storage variations from remote sensing data. Adv. Space Res. 47, 1497–1507 (2011).

Rodell, M. et al. The global land data assimilation system. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 85, 381–394 (2004).

Good, S. A., Martin, M. J. & Rayner, N. A. EN4: Quality controlled ocean temperature and salinity profiles and monthly objective analyses with uncertainty estimates. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 118, 6704–6716 (2013).

Cowley, R., Wijffels, S., Cheng, L., Boyer, T. & Kizu, S. Biases in expendable bathythermograph data: A new view based on historical side-by-side comparisons. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 30, 1195–1225 (2013).

Levitus, S. et al. Global ocean heat content 1955–2008 in light of recently revealed instrumentation problems. Geophys. Res. Lett. 36, L07608 (2009).

Koch, K.-R. & Kusche, J. Regularization of geopotential determination from satellite data by variance components. J. Geod. 76, 259–268 (2002).

Kusche, J. A Monte-Carlo technique for weight estimation in satellite geodesy. J. Geod. 76, 641–652 (2003).

Teunissen, P. J. & Amiri-Simkooei, A. Least-squares variance component estimation. J. Geod. 82, 65–82 (2008).

Flechtner, F., Thomas, M. & Dobslaw, H. Improved non-tidal atmospheric and oceanic de-aliasing for GRACE and SLR satellites. In System Earth via Geodetic-Geophysical Space Techniques (eds Flechtner, F. et al.) 131–142 (Springer, 2010).

Chen, J. et al. Error assessment of GRACE and GRACE follow-on mass change. J. Geophys. Res. Earth 126, e2021JB022124 (2021).

Dobslaw, H. et al. Gravitationally consistent mean Barystatic Sea level rise from leakage-corrected monthly GRACE data. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 125, e2020JB020923 (2020).

Ditmar, P. How to quantify the accuracy of mass anomaly time-series based on GRACE data in the absence of knowledge about true signal?. J. Geod. 96, 54 (2022).

Chen, J. L., Wilson, C. R., Li, J. & Zhang, Z. Reducing leakage error in GRACE-observed long-term ice mass change: a case study in West Antarctica. J. Geod. 89, 925–940 (2015).

Sun, Z., Long, D., Yang, W., Li, X. & Pan, Y. Reconstruction of GRACE data on changes in total water storage over the global land surface and 60 basins. Water Resour. Res. 56, e2019WR026250 (2020).

Moriasi, D. N. et al. Model evaluation guidelines for systematic quantification of accuracy in watershed simulations. Trans. ASABE 50, 885–900 (2007).

Nash, J. E. & Sutcliffe, J. V. River flow forecasting through conceptual models part I—A discussion of principles. J. Hydrol. 10, 282–290 (1970).

Klinger, B. & Mayer-Gürr, T. The role of accelerometer data calibration within GRACE gravity field recovery: Results from ITSG-Grace2016. Adv. Space Res. 58, 1597–1609 (2016).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 42474005, 42174014). We thank NASA for providing GRACE mascon and GLDAS models, CSR for providing GRACE mascon, ICGEM for providing spherical harmonic solutions, Hydroweb for providing time series for Caspian Sea level changes, Argo for providing temperature and salinity data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.Y. and K.Q. wrote the main manuscript, X.Y.W., B.Y., J.H.Z., and L.P. revised the manuscript, K.Q. designed the data processing code, J.W.S. and C.L. Checking grammar. All the authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

You, W., Qian, K., Wan, X. et al. Spatial-domain combination of GRACE monthly time-variable gravity models based on multiple weighting strategies and comparison of models’ performance in the Caspian Sea. Sci Rep 15, 3962 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87922-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87922-8