Abstract

The stability design of soil structures, such as retaining walls, has traditionally relied on deterministic analyses that use averaged soil parameters. However, modern computational advances, particularly Monte Carlo simulations (MCs), have highlighted the limitations of this approach. Engineers are now increasingly focused on understanding the probability of failure (PF) associated with specific safety factors. This study explores the impact of spatial variability in soil properties, specifically the friction angle and unit weight, on PF. By applying log-normal distributions and spatial correlation lengths, extensive MC simulations were combined with finite element limit analysis to establish relationships between safety factors and PF. This research makes several contributions to geotechnical engineering. It integrates MC simulations with finite element limit analysis to provide a statistically robust framework for evaluating PF in soil structures. The use of adaptive finite element meshes introduces new insights into failure mechanisms, addressing gaps in existing studies. Additionally, the study presents a set of parametric design charts that enable practitioners to estimate PF for specific safety factors effectively. These findings provide practical tools for design engineers, supporting better decision-making and increasing confidence in design outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The estimation of passive earth pressures is a cornerstone in the stability analysis of soil-structure interaction1. Accurate predictions are critical for the safe and reliable design of geotechnical structures. Traditional approaches, including such as Coulomb theory2, Rankine theory3,4, and Log-spiral earth pressure theory5,6, have long provided insights into passive earth pressures by leveraging limit equilibrium principles. However, these methods inherently rely on simplified assumptions, which often do not capture the complexities of real-world conditions. Recent advancements, such as the conservative solution proposed by Nguyen7, Nguyen and Shiau8, have improved predictions of passive earth pressures in cohesionless backfills by accommodating wall geometries, backfill configurations, and variable wall-soil friction angles. Despite these developments, such methods assume idealized homogeneity in soil properties, an assumption rarely met in practice due to the inherent spatial variability of natural soils9.

The impact of spatial variability on geotechnical stability has been a topic of growing interest in recent years. Early work by Fenton et al.10 used random field theory and finite element methods to investigate the influence of spatial variability on lateral thrust in retaining walls, albeit under the assumption of isotropic soil conditions. Subsequent studies expanded this scope by incorporating anisotropic variability. Soubra et al.11 and Rahman and Nguyen12 extended the analysis to shallow footings, considering anisotropic spatial variability in both cohesion and friction angle. Similarly, Vessia et al.13 treated these parameters as anisotropic non-normal random fields for strip footings, further highlighting the importance of stochastic approaches in geotechnical analysis. Haldar and Babu14 explored isotropic spatial variability in laterally loaded pile foundations, while Babu et al.15 and Dodagoudar et al.16 investigated its effects on slope stability and reinforced retaining walls, respectively.

Recent advancements in geotechnical analysis have emphasized the importance of incorporating spatial variability into design models. Javankhoshdel and Bathurst17,18 made significant contributions by investigating the effects of cross-correlation between soil parameters on slope stability. Their work demonstrated that accounting for correlations between properties such as cohesion, friction angle, and unit weight can reduce the probability of failure (PF), resulting in more realistic and less conservative design predictions. Their studies also showed that negative cross-correlations can lower PF for both internal and external failure mechanisms in reinforced slopes. Building on this, Javankhoshdel et al.19 developed a closed-form solution to calculate the reliability index of a limit state function, considering uncertainties in load and resistance terms. Bathurst and Javankhoshdel20 provided a general solution for the probability of failure in simple limit state functions, emphasizing the role of bias and correlations in assessing geotechnical safety. These contributions have advanced the understanding of probabilistic stability, providing engineers with improved design tools.

Probabilistic modeling has further advanced through the integration of Random Finite Element Methods (RFEM) and Monte Carlo simulations. Zhu et al.21 assessed the limit load of passive trapdoors in spatially variable clay, while Dasgupta et al.22 examined active lateral thrust in anisotropic soils. Cheng et al.23,24 conducted comprehensive studies on helical piles and anchors, investigating torque-capacity correlations and uplift behavior in spatially variable soils. Their findings highlight the critical role of soil variability in influencing failure mechanisms and probabilistic design frameworks. Similarly, Chen et al.25 addressed tunneling in non-uniform soils, emphasizing that neglecting spatial variability can lead to underestimated probabilities of failure. These studies underscore the need for probabilistic approaches to address spatial variability in a range of geotechnical applications. RFEM, though powerful for modeling spatially variable soils, has significant limitations. It is computationally intensive, especially for large-scale problems or fine meshes. Its accuracy depends on the quality of random field data and assumes statistical independence, which may not be realistic in complex geotechnical scenarios. These issues highlight the need for more efficient methods like Random Adaptive Finite Element Limit Analysis (RFELA), which optimizes computational efficiency through adaptive meshing, making it ideal for large-scale or highly variable soil applications.

Despite these advancements, a comprehensive set of design charts linking safety factors with the likelihood of failure remains absent from practical use. This critical research gap underscores the urgency for further exploration. It is imperative to provide engineers with essential tools that seamlessly integrate spatial variability, safety factors, and failure probabilities. Our research aims to meet this demand in the complex realm of spatially variable soils. Valuable guidance is offered to the geotechnical engineering community as they navigate the intricate contours of spatially random sands. Random Adaptive Finite Element Limit Analysis (RAFELA), grounded in the OPTUM CE package, represents a robust method that has demonstrated its effectiveness in various geotechnical problems of stability evaluation. For instance, it accurately estimates lateral earth thrust on retaining walls with uniform soil, as demonstrated in prior research by Nguyen and Shiau26. Furthermore, RAFELA has played a pivotal role in the recent work of Shiau on the probabilistic stability design charts in spatially variable clays27.

In this study, practical parameters have been selected for a series of sensitivity studies, leading to the creation of PF charts that encompass a broad range of influential design factors. Furthermore, we offer selected examples of failure mechanisms through Monte Carlo Simulations, giving insights and discussions regarding the fundamental role of random fields in shaping soil failures. This study provides a clearer path forward in addressing the complexities associated with spatially random soils, ultimately enabling better decision-making process in a design process.

Finite element limit analysis (FELA)—deterministic

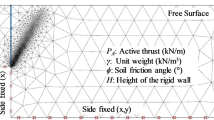

A typical deterministic example of adaptive finite element meshing for the classical passive earth pressure problem is presented in Fig. 1. The rigid wall has a height (H). The face of the rigid wall has a normal compressive pressure (pp) acting inwardly towards the soils to induce a passive failure. The wall-soil interface roughness is taken as perfectly smooth (R = 0) to perfectly rough (R = 1). The backfill sand is considered as a rigid-perfectly plastic Mohr-Coulomb material of a unit weight (γ) and an internal friction angle (φ = 0), while the rigid wall is a rigid elastic material. The standard boundary condition applies to the problem: the two sides are fixed in the normal direction, while the bottom side is fixed in both x and y directions26.

For the deterministic analysis, Shiau and Al-Asadi28,29, Shiau et al.30,31, and Nguyen and Shiau26 has recently reported rigorous upper and lower bound solutions using the three-stability factors approach, i.e., (Fc, Fs, and Fγ). In their study, Terzghi’s bearing capacity equation was modified and the principle of superposition was used to determine limit loads Pp (expressed as pressure in kPa) for a wide range of problems involving cohesion, frictional angle, and surcharge. See Eq. (1).

Following this approach, the current backfill sand problem can be simplified, and a critical stability number (Nc) can be defined as shown in Eq. (2) since c = 0 and σs = 0. Note that, this Nc (Fγ) needs to be timed by 2 to be compatible with the classical passive coefficients (Kpγ), i.e., Kpγ = 2Fγ.

In this section, we aim to validate the upper bound limit analysis model for the deterministic analysis, so that it can be expanded to later random field analysis with confidence in modelling. The proposed upper bound analysis is a nonlinear optimisation problem, which searches a kinematically admissible velocity field, while equating external and internal powers32. The adaptive scheme in Lyamin et al.33 is adopted to improve the accuracy of upper bound solutions. This adaptive scheme considers the internal dissipation calculated from the deviatoric stresses and strain rates (or called as shear power) as the control variable. In all numerical runs of the paper, three iterations of adaptive meshing were used, with the number of elements ranging from 3000 to 5,000 as suggested in OptumCE G2 34. To ensure the accuracy and reliability of the results, a convergence study was conducted, demonstrating that the chosen number of elements and adaptive iterations provided sufficiently accurate solutions while balancing computational efficiency. The convergence study confirmed that the selected range of elements and the level of adaptive iterations were adequate for the analyses performed. For the deterministic scenario, the maximum error, calculated as (upper bound -lower bound)/ (upper bound + lower bound), was found to be less than±1%.

Table 1 provides a valuable snapshot of the obtained results in comparison to those derived from well-established methods with input parameters: H = 4.5 m, c = 0, ϕ = 30˚, γ = 18 kN/m3. This comparative analysis not only instils a sense of greater confidence in the accuracy and reliability of our findings but also serves as a crucial foundation for the subsequent in-depth exploration involving random field studies and thousands of Monte Carlo simulations in the following section.

Finite element limit analysis (FELA)—random field

Random field theory

In geotechnical engineering of random field analysis for the spatial variation of sand, it is common to use a lognormal distribution of soil friction angle (φ). This is to ensure that positive variables are always assigned. In comparison with normal distributions (see Eq. (3)), undesirable negative random variables for (φ) can always be avoided.

In Eq. (3), The parameter u is the mean, while the parameter σ is its standard deviation. Note that the log-normal distribution is simply derived as the exponential function of a normal distribution curve. Therefore, the lognormal distribution is expressed by Eq. (4), which is also known as the probability density function (PDF). See Eqs. (4)–(6).

where,

Shown respectively in Eqs. 5 and 6 are the mean (µ) and standard deviation (σ) of soil internal friction angle (φ). Note that the coefficient of variation (COV), defined as the standard deviation over the mean, is a useful parameter in practice, as it can be used to describe the probable range of soil variability.

The cumulative distribution function (CDF) is another way to describe the probability of a random variable, and it can be obtained by integrating the probability density function (PDF) in Eq. (4). This is shown in Eq. 7 where erfc is the complementary error function35,36.

The histogram shown in Fig. 2 is a convenient way to observe the probability of a random variable, such as the factor of safety (FoS). In this demonstration of (COV = 15%, SCLR = 0.6), one can conveniently observe the probability of FoS ≤ 1 by inspecting the CDF curve. In this case, it is approximately equal to 21%, which can also be estimated by using the area under the red PDF curve for (0 ≤ FoS ≤ 1).

Apart from the mean and the coefficient of variation (COV) stated above, it is important to characterize the spatial variability. The use of the scale of fluctuation (Ѳ) is common to facilitate the implementation of a random field in the two-dimensional space. A spatial correlation length (SCL) is defined in the exponential correlation function ρ, and it is represented by both SCLx and SCLy that are the x and y distances between two points in random soils. Equation (8) is used to describe the random field.

where \({\tau _{xij}}\) and \({\tau _{yij}}\) are the absolute horizontal and vertical distances between two discrete points (i, j).

Small values of SCLx, y would indicate a highly variable random field. As the value of SCLx, y is close to zero, impulsive and unpredictable random field can be expected, and every point in the random field may be independent from each other. In contrast, large values of SCLx, y would yield a smooth varying field. Theoretically speaking, the soil becomes homogeneous when the values of SCLx, y are immeasurably large. For the present study of passive earth pressures, SCLx = SCLy, i.e., the horizontal correlation length is equal to the vertical correlation lengths. Accordingly, a dimensionless ratio is adopted for the correlation length (SCLR) throughout the study, and it is defined as in Eq. (9).

where H is the height of the rigid wall (see Fig. 1).

A random field analysis needs a mean value of u and a standard deviation σ. It also requires the knowledge of spatial correlation lengths SCLx, y. With these, an expansion method, such as the Karhunen-Loeve (KL) method, is selected in the study to simulate reliable random fields for stability analyses using the finite element limit analysis. The method literally calculates the covariance of two random variables and assists in implementing thousands of random field realizations. Also note that both eigenvalues and eigenvectors of the covariance function are estimated by using the KL method. More details of the method can be found in Betz et al.37, Adhikari and Friswell38, Zheng et al.39.

(COV = 20, SCLR = 1)

One thousand Monte Carlo simulations (MCs) are selected, following those previous random field studies of soil variability35,36,40,41,42,43,44. Figure 3 shows a typical scatter plot for the stability number Nc with 1000 MCs. Each dot represents the resulting Nc from a FELA analysis with the corresponding random field relization. A total of one thousand Monte Carlo simulations (MCs, 1000 dots) are done. For this particular case (COV = 15%, SCLR = 0.6), the mean value of the one thousand Nc values is Nc, m = 1.518, i.e., the horizontal line drawn on the figure.

Another useful plot for general observation is the spatially random distribution of ϕ. A general observation of how the random field distribution may look would help in enhancing the modelling confidence as well as understanding the later probability interpretation. This is shown in Fig. 4 for the various seed numbers (Seed = 1; 500; and 1000) within the 1000 MCs. The selected case for this demonstration is for (COV = 20, SCLR = 1). “Seed” is used in the Monte Carlo simulations using the OptumCE code. It literally means the simulation number. Although these demonstration plots (Figs. 2, 3 and 4) are just for illustration purpose only, they do have a significant role in facilitating the tedious process of random field analyses.

The above random field theory has been implemented in the latest version of FELA program (Optum CE, G2). More details on the modelling will be discussed in the next section.

Random adaptive FELA

Random Finite Element Limit Analysis (RFELA) has been used for addressing issues concerning slope reliability and the probabilistic assessment of bearing capacity40,41,42. Nonetheless, most of the works involved the utilization of uniform meshes, a technique notorious for its time-consuming nature in the pursuit of precise boundary solutions. Random Adaptive Finite Element Limit Analysis (RAFELA) provides a groundbreaking innovation, seamlessly combines adaptive mesh refinement with finite element limit analysis to probabilistic challenges35,36,43,45.

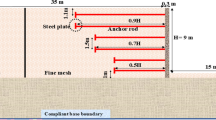

Using upper limit analysis, the present study employs two types of meshing schemes: adaptive meshes (Fig. 5) and uniform meshes (Fig. 6). Both schemes are utilized to investigate key probability of failure (PF) design parameters, including the coefficient of variation (COV), the spatial correlation length ratio (SCLR), and the factor of safety (FoS). Note that the meshes shown in Figs. 5 and 6 follow the same notations and boundary conditions as described earlier for the deterministic analysis. For the random field problem, only a perfectly smooth wall (R = 0) is considered to focus on the effects of spatial variability. To obtain accurate solutions of this problem, all the numerical models are created carefully to make sure that the domain is sufficiently large to avoid potential boundary effects. Apart from those modelling details explained in deterministic analysis, the Karhunen-Loeve (KL) expansion method and 1000 MCs are adopted in all analyses throughout the random field study of the paper.

Using the critical stability number (Nc) in Eq. (2), several sets of probabilistic design charts are presented for practical design uses considering the random field of soil properties. The selected range of the three parameters are: (1) COV = 5–30%; (2) SCLR = 0.2 to 2.0; (3) FoS = 0.5 to 2.5. Other parameters, such as the mean undrained shear strength (µsu), are taken as 30°, and the mean soil unit weight (γ) is 18 kN/m³. While the variability of γ is generally insignificant as established by past studies40,46,47, a higher COV of up to 30% was included in this study to perform a sensitivity analysis and explore its impact in extreme cases. Although typical COV values for ϕ are below 20% and for γ below 10%, these higher values were used to assess the influence of greater variability on the probability of failure (PF). This assumption is made for exploratory purposes, and it is recommended that practitioners apply site-specific, realistic variability ranges for ϕ and γ in practical design applications.

Using the critical stability number (Nc) in Eq. (2), several sets of probabilistic design charts are presented for practical design uses considering the random field of soil property. The selected range of the three parameters are: (1) COV = 5–30% (2) SCLR = 0.2 to 2.0; (3) FoS = 0.5 to 2.5. Other parameters such as the mean undrained shear strength (µsu) is taken as 30°, and the mean soil unit weight (γ) is 18 kN/m3.

It is important to note that the assumption of spatial variability may be more significant in certain conditions, such as in natural or poorly compacted soils. However, for retaining structures with compacted or engineered backfills, the effect of spatial variability may be minimal due to the low variability intentionally introduced during construction. In these cases, the influence of spatial variability on the factor of safety (FoS) and the probability of failure (PF) could be reduced. Therefore, while the presented design charts account for a wide range of soil conditions, engineers should consider the specific characteristics of the backfill when applying these results, particularly in instances where soil variability is controlled.

Mean critical stability number Nc, m

To deepen the understanding of the PF investigation, the mean critical stability numbers Nc, m is divided by the deterministic critical stability number Nc, d, and they are presented for various spatial correlation length ratios (SCLR) and coefficients of variation (COV), as shown in Figs. 7 and 8.

Numerical results shown in Fig. 7 are mainly for the adaptive meshing. Selected results of uniform meshing are also presented in the figure for comparison purpose, and they show a good agreement between the two solutions. In general, the ratio of (Nc, m/Nc, d) increases as the value of SCLR increases. This is observed for all values of COV. This trend can be attributed to the effect of spatial correlation on soil variability. As SCLR increases, the spatial variability of soil parameters, such as friction angle and unit weight, becomes more pronounced over larger spatial domains. This increased spatial correlation means that areas of high or low soil strength tend to cluster together, leading to more significant variations in the overall stability of the soil structure48. Nevertheless, there are two distinct regions to be discussed. Noting that the values of (Nc, m/Nc, d) fall below 1 when SCLR is smaller than approximately 0.65, the larger the COV the smaller the (Nc, m/Nc, d). In contrast, for SCLR > 0.65, the values of (Nc, m/Nc, d) are all above 1, and as SCLR further increases, the larger the COV the greater the (Nc, m/Nc, d). The increase in (Nc, m/Nc, d) with SCLR can be further explained by the theory of random fields, whereas spatial correlation length increases, the spatial variability of soil properties becomes more predictable over larger areas, leading to less extreme variations and more stable behavior in some regions. This can result in higher mean stability numbers when averaged over a larger area. Empirical evidence from studies by Griffiths and Fenton49 and Chakraborty and Dey50 supports this observation, showing that increased spatial correlation in soil properties can lead to higher average stability factors in soil-structure interaction problems.

Using the same data, Fig. 8 further study the relationships between (Nc, m/Nc, d) and COV for the various values SCLR. Our findings reveal a compelling consistency in numerical outcomes, underscoring the harmonious alignment between results obtained through uniform and adaptive meshing techniques. Overall, numerical results have shown that, for a given value of SCLR, |(Nc, m/Nc, d)-1| is the largest when COV = 30%. Knowing that a large value of COV means highly variable random soils, the absolute values of |(Nc, m/Nc, d)-1| should therefore be the largest when COV = 30%. The observed trend has significant implications for geotechnical design, as understanding how spatial correlation affects the mean stability number aids in designing more reliable and robust structures by considering the influence of spatial variability on stability predictions46. An interesting finding is that approximately a horizontal line may result along Nc, m/Nc, d =1 when SCLR is approximately equal to 0.65, This has suggested that, when SCLR = 0.65, the value of (Nc, m/Nc, d) is independent of COV% and it is equal to unity.

In validating the numerical methods, adaptive meshing techniques were employed alongside uniform meshing, demonstrating a high degree of consistency and accuracy. Convergence studies confirmed that the adaptive meshing provided robust results, even in scenarios with high soil property variability, as indicated by the largest absolute values of (Nc, m/Nc, d − 1) at COV = 30%. These findings are consistent with those in the literature, such as by Ali et al.44, reinforcing the validity of our approach.

The application of adaptive and uniform meshing within the Finite Element Method (FEM) ensured the robustness of the numerical results. The adaptive meshing technique, in particular, focused computational resources on areas with significant stress or deformation changes, leading to more precise results. Consistency across these techniques highlights the reliability of our numerical model, as supported by studies from Ali et al.44 and Lyamin et al.51. Additionally, the integration of Monte Carlo simulations enabled the assessment of spatial variability, further enhancing the reliability of the stability analysis.

Probabilistic Interpretation and PF

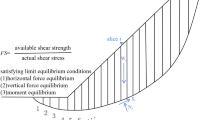

Earlier in the paper, a critical stability factor Nc for the passive sand problem was defined for deterministic analysis in Eq. (2). Therefore, for the probabilistic analysis in this section, a passive failure is identified as the calculated Nc value of each MCs (out of the 1000 MCs) is less than (Ncd/FoS), i.e., the deterministic Ncd over a designated value of FoS. See Eq. (9).

With Eq. (10), we can then calculate PF for a “designed” value of FoS. This can be simply done by counting the number of occurrences (or frequency) from Eq. 10 and dividing it by the total number of MCs (i.e., 1000 MCs in this paper). This process is further presented as in Eq. (11).

With the probabilistic interpretation in Eq. (11), we can then study the effects of the random field design parameters such as COV, SCLR, and FoS. It is important to be noted that the computational effort is now 1000 times more than a deterministic analysis. Numerical results for the study are presented in Figs. 9, 10, 11 and 12, and they are discussed next.

The variations of PF with COV for the various FoS = (0.5, 1, 1.25, 1.5, 2, and 2.5) are shown in Fig. 9. The selected study for this figure is for SCLR = 0.2. For a design of FoS = 0.5, the horizontal line along PF = 1.0 would simply mean a 100% probability of failure. This can certainly be understandable for such a low design factor of safety. A factor of safety of 0.5 represents a significantly under-designed scenario where the applied loads or stresses greatly exceed the soil’s capacity. Under these conditions, regardless of the COV, the probability of failure is expected to be 100% because the design is inherently unsafe. For a design of FoS = 1.0, the probability of failure PF increases from 52 to 65% for the range of COV%. This is an important finding that cannot be simply neglected, and it does highlight the importance of a random field study. As the design FoS further increases, it is interesting to see the zero PF shown for (FoS = 1.25 when COV ≤ 12%) and (FoS = 1.5 when COV ≤ 22%), after which PF increases with increasing COV. As the FoS increases to 1.25 and 1.5, the probability of failure decreases significantly and becomes zero when the COV falls below certain thresholds. This behavior is consistent with the principle that increasing the factor of safety improves the robustness of the design. When the variability in soil properties (COV) is sufficiently low, the increased FoS ensures that the soil’s capacity is more than adequate to withstand the applied loads, thus reducing the probability of failure to zero. Finally, for FoS = 2.0 and 2.5, numerical results have all shown zero PF, irrespective of the range of COV values investigated. For these higher FoS values, the probability of failure remains zero across all COV values. This is because these high factors of safety provide a significant margin of safety, making the design robust against variability in soil properties. Even with a high COV, the design remains safe due to the conservative nature of such high FoS values. The reported results have shown a good understanding of PF trends, and they would enhance the confidence in producing all later PF results.

It is a commonly held expectation that an increase in the design factor of safety (FoS) would inherently lead to a decrease in the probability of design failure (PF). This anticipated trend is vividly depicted in Fig. 10, which illustrates the variations of PF concerning different FoS values across various spatial correlation lengths (SCLR). For the purposes of this study, a COV of 30% was chosen. Notably, the intersection point of all curves occurs at approximately FoS = 1.2, which corresponds to a PF of approximately 51%. An intriguing observation becomes known when considering the effect of SCLR. For FoS values greater than or equal to 1.2, a larger SCLR leads to a higher PF, highlighting a reversed effect. Conversely, for FoS values less than or equal to 1.2, a smaller SCLR corresponds to a higher PF, revealing a contrasting relationship. This observation highlights the influence of SCLR on the probability of failure and underscores the importance of selecting appropriate design parameters in geotechnical engineering. Figure 11 presents the same dataset as Fig. 10 but offers a slightly different perspective by interchanging the COV and SCLR values. Noting that an increase in COV generally results in a higher PF and all curves tend to converge toward a constant PF value of approximately 0 at various FoS design levels. This analysis emphasizes that even in designs with higher factors of safety, it is crucial to consider both spatial correlation and coefficient of variation to accurately predict the probability of failure and ensure robust geotechnical designs. This analysis sheds light on the influence of COV and SCLR values on the PF, offering valuable insights for geotechnical design considerations.

The numerical results presented so far have convinced us to further prepare a comprehensive collection of PF design charts for practical uses, and these charts are to be discussed in the next section. Nevertheless, it is also important to examine and demonstrate some examples of associated failure mechanisms of random passive earth pressures. It is proposed to use the contour plots of principal strain differences |ε1 - ε3|, as that would provide information on the non-zero maximum shear strains. Although the presented “possible” failure mechanisms are only for illustration purposes, as they are only selected from the 1000 MCs scenarios, it may be important to be aware of the possible failure slip lines as a result of the very different scenarios during the 1000 MCs.

Figure 12 provides an insightful display of contour plots depicting the principal strain difference |ε1 - ε3| across a spectrum of spatial correlation lengths (SCLR). This selected presentation is for a constant coefficient of variation (COV) at 30% and a consistent seed number of 555. On the other hand, Fig. 13 offers a similar representation of this data but with a focus on varying seed numbers while keeping COV at 30% and SCLR at 0.6. What emerges as particularly captivating is the rich tapestry of “potential” failure mechanisms that unfolds from the extensive Monte Carlo simulations (MCs) and Finite Element Limit Analysis (FELA) investigations, as vividly illustrated in both Figs. 12 and 13. Among these mechanisms, one can discern the presence of multiple distinctive slip curves, staggered slip surfaces, and intriguing log-spiral patterns. These findings underline the significance of understanding the complex failure patterns that can occur in real-world scenarios, particularly when dealing with uncertain soil conditions. Such knowledge is crucial for ensuring the reliability and safety of geotechnical designs, especially in large-scale projects where the implications of failure are significant. It is of paramount significance to not only recognize but also understand the existence of these intricate failure patterns, especially when contemplating probability of failure designs for large-scale projects. Noting complexities of these failure modes becomes an essential knowledge in ensuring the reliability and safety of geotechnical designs with uncertainties.

Probabilistic design charts

The aspiration among geotechnical engineers to estimate the probability of failure for practical factor of safety (FoS) values has gained considerable attention in recent years. This desire is akin to meteorologists predicting the likelihood of rain in a weather report, where engineers seek to quantify the “probability” of various outcomes in their designs. In this section, the study approach adopts upper bound limit analysis alongside practical statistical data to present numerical results through design charts. These charts provide a valuable means to assess PF for a chosen FoS, ultimately enabling practitioners to make informed decisions and significantly improve their confidence in the design process.

The presented probabilistic design charts in Figs. 14, 15, 16, 17, 18 and 19 stand as indispensable tools for estimating PF across a range of FoS values spanning from 0.5 to 2.5. They successfully integrate soil variability parameters, specifically, the coefficient of variation (COV) and spatial correlation length (SCLR), into the design framework. To delve deeper, let’s examine the FoS = 0.5 design chart (Fig. 14), which corresponds to a relatively low FoS. Here, it becomes apparent that a small FoS would translate to a high probability of design failure. The figure clearly illustrates that, across all the considered combinations of COV and SCLR values, PF consistently exceeds 0.92 (or 92%). For the FoS = 1.0 design chart (see Fig. 15), a reduction in PF across various COV and SCLR values is expected, and PF now ranges between 50% and 62%, indicating improved design reliability while recognizing the presence of residual risk.

Further increases of FoS would decrease PF, as evidenced in Figs. 16, 17, 18 and 19. Noting that PF consistently experiences a decline, the probability of design failure drastically diminishes to less than 2%, irrespective of the chosen SCLR and COV values with FoS = 2.5, as shown in Fig. 19. However, an interesting trend was observed where, for FoS values greater than or equal to 1.2, a larger SCLR led to a higher PF. Conversely, for FoS values less than or equal to 1.2, a smaller SCLR resulted in a higher PF. This trend can be explained by the impact of spatial variability on soil behavior:

-

For FoS ≥ 1.2: A larger SCLR implies that soil variability is distributed over a larger area. This increased spatial variability introduces greater uncertainty into the analysis, which can lead to a higher PF despite the higher FoS. This phenomenon is supported by findings from studies such as those by Griffiths and Fenton49 and Popescu et al.52.

-

For FoS ≤ 1.2: A smaller SCLR, indicating more localized variability, can have a significant impact on PF. The lower robustness of the design means that localized variability can significantly affect failure probabilities. This observation aligns with theoretical studies by Griffiths and Fenton49 and empirical data from investigations by Srivastava and Babu53.

It can therefore be concluded that a larger FoS significantly attenuates the likelihood of design failure, aligning seamlessly with conservative design principles. Furthermore, these charts unveil another noteworthy trend: an increase in the coefficient of variation (COV) results in a higher probability of design failure (PF) across all SCLR values under consideration.

To illustrate the practical application of the PF charts, a practical example is presented next. For example, to determine the associated PF for a deterministic design characterized by a FoS of 1.5, the values of COV and SCLR are acquired through a site investigation, and in this hypothetical case, we assume COV is 15%, and SCLR is 1. Referring to Fig. 17, PF can be estimated as 0.045 or 4.5%. This calculation furnishes valuable insights into the reliability of the selected design parameters. It’s crucial to emphasize that the acceptable PF value in a design context can vary following the specific requirements and constraints of a project. Nonetheless, it is agreeable that a PF below 5% would provide a high level of confidence in the design’s reliability.

Conclusions

Griffiths et al.54 pioneered a study on the reliability of passive earth pressure in sands using elastoplastic finite element method. This problem was revisited in this paper using rigorous upper bound limit analysis technique with finite elements and random field Monte Carlo simulations. The technical investigation began with a comparison of two types of finite element meshes; namely the uniform and the adaptive meshes. It continued to investigate the trends of mean critical stability ratio (Nc, m/Nc, d) under various values of coefficient of variation (COV) and spatial correlation length rations (SCRL). The study was then followed by presenting the effects of COV, SCRL, and FoS on the predicted probability of failures (PF). Finally, several contour design charts were produced for quick references on the associated PF for a given factor of safety (FoS), as well as known values of COV and SCRL. The following conclusions can be drawn based on the current study.

-

Consistent results were observed when comparing the outcomes obtained from uniform and adaptive meshes, underscoring the robustness of our findings. Notably, the adaptive mesh, with its unique capability to reveal the final failure mechanism, offered a distinct advantage in enhancing our understanding of the studied phenomena.

-

The study for the mean critical stability ratio (Nc, m/Nc, d) under various COV and SCRL showed good trends with the parametric changes. Together with the presented histogram and selected cases for the demonstration of random variables distribution, it greatly enhanced the confidence of the random field study.

-

The utilization of contour plots, showcasing non-zero principal strain differences |ε1 - ε3| across varying values of spatial correlation length (SCRL) and distinct “seed” numbers, proved to be a highly effective method for elucidating numerous potential failure mechanisms across the extensive Monte Carlo simulations (MCs). These visual representations not only explained the diverse array of failure scenarios, but also provided invaluable insights into the intricate interplay of design factors influencing the soil stability.

-

An extensive array of parametric investigations, spanning across coefficient of variation (COV), spatial correlation length (SCRL), and factor of safety (FoS) were investigated. Notably, it became evident that the probability of failure (PF) exhibited an upward trajectory with increasing COV. Furthermore, the magnitude of FoS had a profound influence, with larger FoS values corresponding to greater PF, aligning closely with conservative design principles. The relationship between SCRL and PF, however, revealed a nuanced complexity: the outcome hinged on the specific interplay of FoS and COV values, with SCRL potentially triggering both increases and decreases in PF.

In this study, we introduced several innovative approaches that distinguish our work from previous research in this area. First, the integration of Monte Carlo simulations with finite element limit analysis provided a rigorous and statistically robust framework for evaluating the probability of failure (PF) in soil structures. Second, the use of adaptive finite element meshes in stochastic analyses offered new insights into failure mechanisms, contributing to a deeper understanding of the complex interplay between design parameters. Third, our comprehensive parametric studies have yielded valuable insights to the problem and provided practical tools for practitioners. The probability of design failure (PF) investigation process and the resulting PF design charts, presented in this paper, facilitate the connection between a chosen design factor of safety and the associated likelihood of design failure. These tools can be readily employed not only for the specific problem at hand but also for the exploration of random fields in a wide range of geotechnical stability issues. Fourth, the contour design charts developed in this study serve as practical tools for geotechnical engineers, enabling a more efficient and informed assessment of PF for various factors of safety (FoS). These charts represent a significant advancement in providing accessible design aids for practitioners.

The present study has certain limitations. The use of SCLx= SCLy in all analyses is not a rigorous approach in stochastic analysis, although this is the first assumption that we must make in the current study. Future work directions are to consider the effects of varying spatial correlation lengths in both directions. It was noted that, with a mean of 30 degrees of soil frictional angle and COV = 5–30%, some results shall be neglected as they are impractically small with large value of COV. Despite the common use of 1000 MCs in most published random field studies of geotechnical stability problems, it is recommended to increase the numbers in the future to achieve conservative solutions. In this study, there is no correlation between soil unit weight and internal friction angle. We simply adopted the same random parameters for both the soil unit weight and internal friction angle. Future work directions are to consider the correlation between soil unit weight and internal friction angle. The final recommendation for future work is to consider the effect of dilation angle in random field study.

Limitations and future work

The failure probability (PF) values in Figs. 14, 15, 16, 17, 18 and 19 are based on specific mean values of soil parameters used in the Monte Carlo simulations. If the mean values change, the PF values may no longer apply. Future work should focus on recalibrating the charts or conducting additional Monte Carlo simulations with varying mean values to ensure applicability for site-specific conditions. Additionally, incorporating cross-correlation between soil parameters, as discussed by Javankhoshdel and Bathurst18, and addressing the limitations of isotropic spatial variability by incorporating anisotropic models, as suggested by Luo, Bathurst, and Javankhoshdel55, could improve the accuracy and robustness of the analysis.

For FS values not presented in the charts, interpolation is applicable assuming a smooth relationship between FS and PF. However, caution is needed for extreme values, and further simulations or FEM analyses may be required for more accurate estimates. These advancements will enhance the practical use and reliability of the design charts.

Data availability

All data, models, or code that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CDF:

-

Cumulative distribution function

- COV:

-

Coefficient of variation

- FELA:

-

Finite Element Limit Analysis

- FoS:

-

Factor of safety

- KL:

-

Karhunen-Loeve

- MCs:

-

Monte Carlo simulations

- Nc :

-

The critical stability number

- Nc,d :

-

The deterministic critical stability number

- Nc,m :

-

The mean critical stability numbers

- PDF:

-

Probability density function

- PF:

-

Probability of Failures

- RAFELA:

-

Random Adaptive Finite Element Limit Analysis

- RF:

-

Random Field

- RFEM:

-

Random Finite Element Method

- SCLx, SCLy:

-

The x and y distances between two points in random soils

- SCLR:

-

Spatial correlation length ratio

- Pp:

-

Passive Thrust

- c:

-

The cohesion of soil

- Fc :

-

The factor of cohesion

- σs :

-

The surcharge

- Fs :

-

The factor of surcharge

- γ:

-

Unit weight

- Fγ :

-

The factor of unit weight

- ϕ:

-

The internal friction angle of soil

- Kpγ :

-

The classical passive coefficients

- R:

-

The roughness of retaining wall

- H:

-

The height of retaining wall

- µ:

-

The mean

- σ:

-

Standard deviation

- erfc:

-

The complementary error function

- \({\tau _{xij}}\),\({\tau _{yij}}\) :

-

The absolute horizontal and vertical distances between two discrete points (i, j)

- µsu :

-

The mean undrained shear strength

References

Duncan, J. M. & Mokwa, R. L. Passive Earth Pressures: Theories and Tests. Journal of Geotechnical and Geoenvironmental Engineering 127, 248–257. (2001). https://doi.org/10.1061/(asce)1090-0241127:3(248) (2001).

Coulomb, C. A. Essai sur une application des regles de maximis et minimis a quelques problemes de statique relatifs a 1’architecture. Mem. Div. Sav. Acad. (1773).

Rankine, W. J. M. II. On the stability of loose earth. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond., 9–27 (1857).

Xu, S. Y., Lawal, A. I., Shamsabadi, A. & Taciroglu, E. Estimation of static earth pressures for a sloping cohesive backfill using extended Rankine theory with a composite log-spiral failure surface. Acta Geotech. 14, 579–594. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11440-018-0673-2 (2018).

Shields, D. H. & Tolunay, A. Z. Passive pressure coefficients by method of slices. J. Soil. Mech. Found. Div. 99, 1043–1053. https://doi.org/10.1061/jsfeaq.0001968 (1973).

Terzaghi, K. Theoretical Soil Mechanics John Wiley and Sons Inc. New York 314 (1943).

Nguyen, T. Passive earth pressures with sloping backfill based on a statically admissible stress field. Comput. Geotech. 149, 104857. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compgeo.2022.104857 (2022).

Nguyen, T. & Shiau, J. Passive earth pressure in sand on inclined walls with negative wall friction based on a statically admissible stress field. Acta Geotech. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11440-024-02278-z (2024).

Phoon, K. K. et al. Geotechnical uncertainty, modeling, and decision making. Soils Found. 62, 101189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sandf.2022.101189 (2022).

Fenton, G. A., Griffiths, D. V. & Williams, M. B. Reliability of traditional retaining wall design. Géotechnique 55, 55–62. https://doi.org/10.1680/geot.2005.55.1.55 (2005).

Soubra, A. H., Abdel Massih, Y. & Kalfa, M. D. S. Bearing capacity of foundations resting on a spatially Random Soil. 66–73. (2008). https://doi.org/10.1061/40971(310)8

Rahman, M. M. & Nguyen, H. B. K. in The Sixth International Conference on Advanced Engineering Computing and Applications in Sciences. 53–58.

Vessia, G., Cherubini, C., Pieczyńska, J. & Puła, W. Application of random finite element method to bearing capacity design of strip footing. J. GeoEngineering. 4, 103–112 (2009).

Haldar, S. & Babu, G. L. S. Effect of soil spatial variability on the response of laterally loaded pile in undrained clay. Comput. Geotech. 35, 537–547. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compgeo.2007.10.004 (2008).

Babu, G. L. S., Reddy, K. R. & Srivastava, A. Influence of spatially variable Geotechnical properties of MSW on Stability of Landfill slopes. J. Hazard. Toxic. Radioactive Waste. 18, 27–37. https://doi.org/10.1061/(asce)hz.2153-5515.0000177 (2014).

Dodagoudar, G., Sayed, S. & Rajagopal, K. Random field modeling of reinforced retaining walls. Int. J. Geotech. Eng. 9, 229–238. https://doi.org/10.1179/1939787914y.0000000055 (2014).

Javankhoshdel, S. & Bathurst, R. J. Deterministic and probabilistic failure analysis of simple geosynthetic reinforced soil slopes. Geosynthetics Int. 24, 14–29. https://doi.org/10.1680/jgein.16.00012 (2017).

Javankhoshdel, S. & Bathurst, R. J. Influence of cross correlation between soil parameters on probability of failure of simple cohesive and c-ϕ slopes. Can. Geotech. J. 53, 839–853. https://doi.org/10.1139/cgj-2015-0109 (2016).

Javankhoshdel, S., Bathurst, R. J. & Cami, B. Influence of model type, bias and input parameter variability on reliability analysis for simple limit states with two load terms. Comput. Geotech. 97, 78–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compgeo.2018.01.002 (2018).

Bathurst, R. J. & Javankhoshdel, S. Influence of model type, bias and input parameter variability on reliability analysis for simple limit states in soil–structure interaction problems. Georisk: Assess. Manage. Risk Eng. Syst. Geohazards. 11, 42–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/17499518.2016.1154160 (2016).

Zhu, D., Griffiths, D. V., Huang, J., Gao, Y. & Fenton, G. A. Probabilistic analysis of shallow Passive Trapdoor in Cohesive Soil. J. Geotech. GeoEnviron. Eng. 145, 85–88. https://doi.org/10.1061/(asce)gt.1943-5606.0002051 (2019).

Dasgupta, U. S., Chauhan, V. B. & Dasaka, S. M. Influence of spatially random soil on lateral thrust and failure surface in earth retaining walls. Georisk: Assess. Manage. Risk Eng. Syst. Geohazards. 11, 247–256. https://doi.org/10.1080/17499518.2016.1266665 (2016).

Cheng, P., Guo, J., Yao, K. & Chen, X. Numerical investigation on pullout capacity of helical piles under combined loading in spatially random clay. Mar. Georesources Geotechnology. 41, 1118–1131. https://doi.org/10.1080/1064119x.2022.2120843 (2022).

Cheng, P., Liu, F., Chen, X., Zhang, Y. & Yao, K. Estimation of the installation torque–capacity correlation of helical pile considering spatially variable clays. Can. Geotech. J. 61, 2064–2074. https://doi.org/10.1139/cgj-2023-0331 (2024).

Chen, X. J. et al. Influence of cutterhead opening ratio on soil arching effect and face stability during tunnelling through non-uniform soils. Undergr. Space. 17, 45–59 (2024).

Nguyen, T. & Shiau, J. Revisiting active and Passive Earth pressure problems using Three Stability factors. Comput. Geotech. 163, 105759. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compgeo.2023.105759 (2023).

Shiau, J. & Keawsawasvong, S. Probabilistic Stability design charts for shallow Passive trapdoors in spatially variable clays. Int. J. Geomech. 23 https://doi.org/10.1061/ijgnai.gmeng-7902 (2023).

Shiau, J. & Al-Asadi, F. Two-dimensional tunnel heading stability factors F. F F Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 97, 103293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tust.2020.103293 (2020).

Shiau, J. & Al-Asadi, F. Determination of critical tunnel heading pressures using stability factors. Comput. Geotech. 119, 103345. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compgeo.2019.103345 (2020).

Shiau, J., Keawsawasvong, S. & Yodsomjai, W. Determination of support pressure for the design of Square Box culverts. Int. J. Geomech. 23 https://doi.org/10.1061/(asce)gm.1943-5622.0002620 (2023).

Shiau, J., Nguyen, T. & Ly-Khuong, D. Unraveling seismic uplift behavior of plate anchors in frictional-cohesive soils: a comprehensive analysis through stability factors and machine learning. Ocean Eng. 297, 116987. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oceaneng.2024.116987 (2024).

Sloan, S. W. Geotechnical stability analysis. Géotechnique 63, 531–571. https://doi.org/10.1680/geot.12.RL.001 (2013).

Lyamin, A. V., Sloan, S. W., Krabbenhøft, K. & Hjiaj, M. Lower bound limit analysis with adaptive remeshing. Int. J. Numer. Methods Eng. 63, 1961–1974. https://doi.org/10.1002/nme.1352 (2005).

OptumG, O. & Copenhagen Denmark: optum computational engineering. See (2020). https://optumce.com/. Accessed 1.

Wu, G., Zhao, H. & Zhao, M. Undrained stability analysis of strip footings lying on circular voids with spatially random soil. Comput. Geotech. 133, 104072. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compgeo.2021.104072 (2021).

Wu, G., Zhao, H., Zhao, M. & Zhu, Z. Stochastic analysis of dual tunnels in spatially random soil. Comput. Geotech. 129, 103861. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compgeo.2020.103861 (2021).

Betz, W., Papaioannou, I. & Straub, D. Numerical methods for the discretization of random fields by means of the Karhunen–Loève expansion. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 271, 109–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cma.2013.12.010 (2014).

Adhikari, S. & Friswell, M. I. Distributed parameter model updating using the Karhunen–Loève expansion. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 24, 326–339. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymssp.2009.08.007 (2010).

Zheng, Z., Beer, M. & Nackenhorst, U. An iterative multi-fidelity scheme for simulating multi-dimensional non-gaussian random fields. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 200, 110643. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymssp.2023.110643 (2023).

Kasama, K. & Zen, K. The Reliability Assessment for Slope Stability Considering the spatial variability of Soil Strength using Random Field Numerical Limit analyses. J. Soc. Mater. Sci. Japan. 59, 336–341. https://doi.org/10.2472/jsms.59.336 (2010).

Kasama, K. & Whittle, A. J. Bearing capacity of spatially Random Cohesive Soil using Numerical Limit analyses. J. Geotech. GeoEnviron. Eng. 137, 989–996. https://doi.org/10.1061/(asce)gt.1943-5606.0000531 (2011).

Huang, J., Lyamin, A. V., Griffiths, D. V., Krabbenhoft, K. & Sloan, S. W. Quantitative risk assessment of landslide by limit analysis and random fields. Comput. Geotech. 53, 60–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compgeo.2013.04.009 (2013).

Ali, A., Lyamin, A. V., Huang, J., Sloan, S. W. & Cassidy, M. J. Undrained stability of a single circular tunnel in spatially variable soil subjected to surcharge loading. Comput. Geotech. 84, 16–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compgeo.2016.11.013 (2017).

Ali, A. et al. Probabilistic stability assessment using adaptive limit analysis and random fields. Acta Geotech. 12, 937–948. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11440-016-0505-1 (2016).

Brahmi, N., Ouahab, M. Y., Mabrouki, A., Benmeddour, D. & Mellas, M. Probabilistic analysis of the bearing capacity of inclined loaded strip footings near cohesive slopes. Int. J. Geotech. Eng. 15, 732–739. https://doi.org/10.1080/19386362.2018.1496005 (2018).

Phoon, K. K. & Kulhawy, F. H. Characterization of geotechnical variability. Can. Geotech. J. 36, 612–624 (1999).

Pan, Q. & Dias, D. Probabilistic evaluation of tunnel face stability in spatially random soils using sparse polynomial chaos expansion with global sensitivity analysis. Acta Geotech. 12, 1415–1429. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11440-017-0541-5 (2017).

Alamanis, N. & Dakoulas, P. Impact of Soil Properties’ spatial correlation lengths and inclination on permanent slope displacements due to Earthquake Excitation. Appl. Sci. 13, 9868. https://doi.org/10.3390/app13179868 (2023).

Griffiths, D. V. & Fenton, G. A. Bearing capacity of spatially random soil: the undrained clay Prandtl problem revisited. Géotechnique 51, 351–359. (2001). https://doi.org/10.1680/geot.2001.51.4.351

Chakraborty, R. & Dey, A. Probabilistic slope stability analysis: state-of-the-art review and future prospects. Innovative Infrastructure Solutions. 7 https://doi.org/10.1007/s41062-022-00784-1 (2022).

Lyamin, A. V., Krabbenhoft, K. & Sloan, S. W. in Proceedings of the VI International Conference on Adaptive Modeling and Simulation. 448–455.

Popescu, R., Deodatis, G. & Nobahar, A. Effects of random heterogeneity of soil properties on bearing capacity. Probab. Eng. Mech. 20, 324–341. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.probengmech.2005.06.003 (2005).

Srivastava, A. & Babu, G. L. S. Effect of soil variability on the bearing capacity of clay and in slope stability problems. Eng. Geol. 108, 142–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enggeo.2009.06.023 (2009).

Griffiths, D. V., Fenton, G. A. & Ziemann, H. R. Reliability of passive earth pressure. Georisk: Assess. Manage. Risk Eng. Syst. Geohazards. 2, 113–121. https://doi.org/10.1080/17499510802178640 (2008).

Luo, N., Bathurst, R. J. & Javankhoshdel, S. Probabilistic stability analysis of simple reinforced slopes by finite element method. Comput. Geotech. 77, 45–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compgeo.2016.04.001 (2016).

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to the reviewers for their valuable feedback and constructive comments, which have significantly contributed to improving the quality and clarity of this manuscript. Their thoughtful suggestions on the methodology, literature review, and assumptions have been invaluable. We appreciate the time and effort they invested in reviewing our work and providing helpful guidance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Jim Shiau: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Supervision, Data Curation, Writing - Original Draft, Writing - Review & Editing, Supervision; Tan Nguyen: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Data Curation, Writing - Original Draft, Writing - Review & Editing, Validation, Supervision; Thinh Pham-Tran-Hung: Visualization, formal analysis, Methodology; Jun Sugawara: Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing - Review & Editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shiau, J., Nguyen, T., Pham-Tran-Hung, T. et al. Probabilistic assessment of passive earth pressures considering spatial variability of soil parameters and design factors. Sci Rep 15, 4752 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87989-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87989-3