Abstract

Landslides are among the most frequent and dangerous geological disasters worldwide, making accurate landslide susceptibility mapping (LSM) crucial for effective disaster prevention. This study introduces a novel LSM framework by integrating random forest (RF), support vector machine (SVM), and catastrophe theory (CT), and applies it to the contiguous impoverished areas of Liangshan, Sichuan. First, we selected 12 factors representing both internal environmental and external triggering conditions to assess landslide susceptibility. The frequency ratio method was used to assess the correlation between historical landslides and these factors. Second, CT was integrated into the RF- and SVM-based LSM models, resulting in two integrated models (RF-CT and SVM-CT) for generating LSM in the region. Finally, the receiver operating characteristic curve was used to evaluate and compare the accuracy of the methods. The results show that the RF-CT and SVM-CT frameworks performed well, with a 10% improvement in the success rate (0.899 for RF-CT and 0.873 for SVM-CT), and a 5% improvement in the prediction rate (0.783 for RF-CT and 0.775 for SVM-CT) compared with the individual RF and SVM models. These findings provide valuable insights for disaster prevention, poverty alleviation, and sustainable development in the study area.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A landslide is the downward movement of rocks, soil, and organic material along a slope under the influence of gravity1. As a destructive natural disaster, landslides cause extensive damage to vegetation, infrastructure, and property, often resulting in loss of life2. China experiences one of the highest frequencies of landslides globally, particularly in mountainous regions where they hinder resource development and economic growth3,4. The contiguous impoverished areas of Liangshan, Sichuan (CIALS), serve as the core of the Jinsha River Hydropower Base and are a critical region for geological disaster early warning in the Yangtze River Basin. Since the reservoir’s construction and filling, significant changes in the area’s environmental and geological conditions have led to an increase in both the scale and frequency of landslides. These frequent events threaten homes, public infrastructure, and agricultural production, causing casualties and substantial property losses5. Post-disaster recovery often requires significant financial resources, but the region’s fragile economic foundation hampers effective reconstruction, exacerbating poverty in the CIALS. High-precision landslide susceptibility mapping (LSM) is essential for prioritizing governance and prevention measures in high-risk areas. It can help reduce the impact of landslides, enhance disaster resilience, and promote sustainable development6. Accurately LSM has thus become a critical priority for disaster management and regional economic development in CIALS.

LSM is an effective approach for reducing and mitigating future landslide-related losses7. It estimates the spatial probability of landslide occurrences, helping to identify high-risk areas. This knowledge is essential for understanding the causes of landslides, predicting future events, and providing a scientific basis for land use planning, major project site selection, and disaster prevention8. With advancements in Geographic information system (GIS) and Remote sensing (RS) technologies, large and complex spatial data can now be processed systematically and efficiently, providing valuable support for large-scale LSM9,10. Researchers have employed various data and methods for LSM, which generally fall into two categories: subjective weighting methods and mathematical model evaluations. Subjective weighting methods, while useful in specific regions, rely heavily on researchers’ knowledge, making them less generalizable11. These methods also struggle to handle high-dimensional, non-normal, and nonlinear data, limiting their adaptability12. Examples include the Delphi method and the Analytic hierarchy process. In contrast, mathematical model-based approaches, particularly those using machine learning (ML), are more objective, replicable, and adaptable to complex data. This has led to their increasing use in LSM. For example, Ngo et al.13 applied Recurrent neural networks and Convolutional neural networks to create a national-scale LSM for Iran, identifying key factors such as slope, geology, land use, and proximity to faults as primary drivers of landslides. Youssef et al.14 compared several advanced ML methods for LSM and found that Random forest (RF) and Linear discriminant analysis outperformed others. Zhang et al.15 developed an LSM model for mountainous areas using the SHapley additive interpretation and eXtreme gradient boosting algorithm, demonstrating better generalization for regions with similar characteristics. These studies have provided scientifically grounded insights into the spatial probability and dynamics of landslide occurrences, aiding prevention efforts. However, the choice of mapping method should be based on the specific characteristics of the study area and the selected evaluation criteria, as the generalization abilities of models can vary regionally.

Recently, mixed and integrated ML models have gained favor among researchers for their superior performance16,17,18. Support vector machine (SVM) is well-suited for handling small sample sizes and providing robust explanations, particularly due to its capacity to process high-dimensional data, generalize effectively, and tackle non-linear problems19. RF is advantageous because it incorporates multiple input factors without excluding any, leading to improved classification outcomes and higher predictive accuracy20. As a branch of nonlinear theory, catastrophe theory (CT) provides an objective approach to address discontinuous changes in natural and social systems, reducing human bias in decision-making and enhancing model generalization21. CT focuses on the phenomena and laws of transition from one stable state to another stable state. It effectively explains sudden phenomena in nature and has wide applications in physics, chemistry, biology, and engineering22. CT has been extensively applied in groundwater potential mapping23, environmental carrying capacity analysis24, and flood and drought risk assessments25. This demonstrates the feasibility of applying CT to landslide susceptibility mapping. Therefore, this study introduced CT when using SVM and RF models for LSM, proposing a new LSM framework and conducting a comparative analysis of its performance. Ultimately, the study aims to generate a reliable landslide occurrence probability distribution map for the CIALS. This map will provide a scientific foundation for comprehensive geological hazard prevention and control, while also supporting the region’s targeted poverty alleviation and ecological protection strategies of the Yangtze River Economic Belt.

Study area

The CIALS is located at 102°12’–103°53’ E and 26°50’–28°53’ N, covering approximately 7,800 square kilometers (Fig. 1). Situated in the transitional zone between the Sichuan Basin and the Yunnan-Guizhou Plateau, the region is deeply cut and eroded by the Jinsha River system. The topography slopes from west to east, with elevations ranging from 4,756 m to 301 m. The region experiences an average annual temperature of 11 °C and receives 500–1000 millimeters of rainfall annually. Its geological structure is complex, and the lithology primarily consists of soft strata and interlayered sandy mudstone from the Cretaceous, Jurassic, and Triassic periods of the Mesozoic Era. According to detailed geological hazard surveys in Sichuan Province, the CIALS contains 471 landslides, including 2 extra-large, 21 large, 112 medium, and 336 small ones.

Data source and conditioning factors

Data preparation and data processing

The data collected for this study include historical landslide inventories, Landsat images, DEM, rainfall data, geological maps, population distribution, and other relevant datasets (Table 1).

The data collection and processing methods are as follows: (1) In 2016, the Sichuan Institute of Geological Survey conducted a comprehensive investigation of landslides in the CIALS. The survey included remote sensing interpretation, field investigation, and data compilation. During the remote sensing phase, high-resolution images and DEMs were used to identify landslides based on key geomorphological features such as flow tracks, head scarps on open slopes, and exposed soil in forests. In the field, landslide data were collected and verified using handheld GPS devices and drones. These landslides were then digitized in ArcGIS software, with attributes such as location and information on threatened buildings, populations, and property. (2) Using the Google Earth Engine platform, Landsat images are employed to obtain the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) of the CIALS. To minimize the impacts of snow, shadows, and clouds, the maximum value synthesis method26 is applied, synthesizing the NDVI data from 2022 to 2024 and yielding the maximum NDVI values during this period. Additionally, land use data is derived from Landsat images using the SVM model, providing information on the distribution of human engineering activities in the CIALS. (3) DEM data is used to extract elevation, slope, plan curvature, relief degree, and water system data. (4) Rainfall data is interpolated into spatial data using Kriging interpolation27. (5) Population density is estimated based on night light data, land use data, and township population statistics28. (6) Peak ground acceleration (PGA) from earthquakes and geological data are processed as vector data, requiring only coordinate transformation. To ensure spatial alignment, all data is projected using the Gauss-Kruger system with a spatial resolution of 100 m × 100 m.

Landslide conditioning factors

Landslides result from the interaction of multiple factors, including geology, topography, meteorology, and human activities29. Currently, there is no unified standard for selecting conditioning factors in LSM. Therefore, based on existing research30,31,32,33 and available data, this study selects 12 conditioning factors from two categories: internal environmental factors and external triggering factors. 8 internal environmental factors were selected based on the following criteria: First, due to the significant altitude difference and deep-cut terrain of CIALS, four topographical factors, namely altitude, slope angle, slope aspect, and plane curvature, were chosen. Second, given the complex and fragmented lithology of the area and the development of geological structures, which are major contributors to landslides, lithology and distance to faults were selected as geological factors. Third, because the area is severely eroded by the Jinsha River system and shows significant spatial variation in vegetation within the dry hot valley, distance to rivers and NDVI were selected. Additionally, 4 external triggering factors were considered: First, frequent earthquakes in the area and surrounding areas are major causes of landslides, so PGA was selected to represent earthquake impact. Second, the concentrated and intense rainfall in the area is a key factor in triggering landslides. Third, there is a large population, most of whom live in river valleys. Large-scale human activities, such as the “Village-to-Village Project” and hydropower development, have induced numerous landslides. Therefore, population density and distance to engineering activities were selected.

When conducting LSM, it is of major importance to recognize the conditioning factors that can cause the landslide and the process that could trigger the movement. The frequency ratio (FR) method relies on the relationship between historical landslide distributions and various conditioning factors, revealing the correlation between landslide locations and these factors34. In this study, the FR method was used to analyze the spatial relationship between historical landslide locations and 12 conditioning factors, providing a basis for LSM modeling (Table 2).

Altitude

As gravity weakens with increasing altitude, loose materials at lower altitudes are more prone to collapse under gravitational force. Therefore, altitude plays a significant role in the distribution of geological hazards35. In this study, altitude was reclassified into 7 categories (Fig. 2a), each with 500-meter intervals, and it was found that the probability of landslides is highest below 2,000 m above sea level.

Slope angle

Slope angle plays a critical role in the formation, development, and susceptibility to landslides, and is widely recognized as a key input parameter in LSM by numerous studies36. In the CIALS, most landslides occur on slopes ranging between 10° and 30° (Fig. 2b).

Slope aspect

Slope aspect indirectly influences landslides and is a crucial factor in LSM37. In this study, slope aspect was reclassified into 9 categories (Fig. 2c), with most landslides concentrated in the east (67.5°–112.5°) and southeast (112.5°–157.5°) directions in the CIALS.

Plan curvature

Hillsides with concave plan curvature are more susceptible to landslides compared to those with convex curvature38. In this study, plan curvature values range from − 49.89 to 53.78 and have been reclassified into 6 categories (Fig. 2d).

Lithology

Lithology significantly influences slope stability, serving as a key factor in LSM39. In the CIALS, lithology is classified into 5 categories: hard rocks, harder rocks, softer rocks, soft rocks, and loose deposits (Fig. 2e). Landslides are predominantly found in regions characterized by softer rocks.

Distance to faults

Fault zones can significantly compromise the integrity and continuity of rock masses, thereby diminishing slope stability40. Additionally, these zones often contain abundant groundwater and exhibit high levels of geological activity, which can further reduce the shear strength of the surrounding rock. Consequently, the fault buffer zone is categorized into 5 classifications (Fig. 2f), and a distance to faults map is created with intervals of 1,000 m.

Distance to rivers

River down cutting creates steep walls or cliffs, making these regions susceptible to landslides41. Therefore, this study establishes 5 river buffer zone categories at intervals of 200 m (Fig. 2g). The analysis reveals that the probability of landslides is significantly higher within the first 200 m from the river compared to other regions.

NDVI

Vegetation plays a crucial role in slope stability by influencing the hydrological and mechanical properties of slopes, thereby impacting landslide occurrences42. In the CIALS, the NDVI values range from − 0.48 to 0.86 and are reclassified into 5 categories using the natural breaks method (Fig. 2h).

PGA

The CIALS is located at the junction of the Longnan-Mabian seismic belt and the Anning River Valley seismic belt in China. The PGA of earthquakes can reflect the seismic load (Fig. 2i), so it is the main external triggering factor43.

10 rainfall

Rainfall is a critical triggering factor for landslides, exerting both direct and indirect effects on their occurrence44. In this study, the annual average precipitation from 15 meteorological stations is utilized to create a rainfall map (Fig. 2j), which is then reclassified into 6 categories at 30-millimeter intervals.

11 Population density

Population density is a significant factor influencing the landslide occurrence45. Higher population density can impact the landscape and environment, potentially increasing landslide risk. Analysis of population density statistics and existing landslide distributions in the CIALS reveals a linear correlation between population density and the probability of landslide occurrence (Fig. 2k).

12 Distance to human engineering activities

Human engineering activities in the CIALS, including road construction, hydropower development, and urban expansion, have intensified, leading to increased damage to mountain slopes46. This trend contributes to slope instability, triggering numerous landslides and reactivating ancient ones. In this study, 5 buffer zone categories are established at intervals of 500 m (Fig. 2l), with landslides predominantly occurring within a distance of less than 500 m from these activities.

Methodology

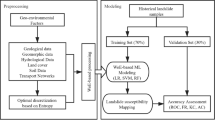

The technical approach of this study comprises 4 key steps (Fig. 3): (1) Sample generation: 10 groups of random samples were created from the historical landslide inventory, with each group divided into a training dataset (70%) and a validating dataset (30%). (2) Conditioning factors selection: Relevant landslide conditioning factors specific to the study area were identified. (3) Model integration: CT was integrated with both SVM and RF models through coordinate transformation and GIS technology to generate LSM. (4) Accuracy assessment: The accuracy and stability of the four methods (RF, SVM, RF-CT, and SVM-CT) were assessed using the Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve across the different random samples.

Support vector machine

SVM is a ML technique widely used for classification, regression, and anomaly detection, particularly effective with linearly inseparable and high-dimensional datasets47. It learns from labeled training data and aims to find the optimal hyperplane that best separates different classes (Fig. 4a). For linearly separable data, SVM identifies the maximum margin hyperplane, ensuring the greatest separation between classes. When the data is not linearly separable, SVM uses kernel functions to map the data into a higher-dimensional feature space, where it then finds the optimal hyperplane. Given a set of samples \(\:\left({x}_{i},{y}_{i}\right)\), the process for determining the optimal hyperplane in SVM is as follows:

In Eq. (1), \(\:\phi\:\) represents the weight vector defining the hyperplane, while \(\:{\delta\:}_{i}\) is the slack variable that permits misclassifications. The condition \(\:{\delta\:}_{i}\ge\:0\) indicates that each point is either on the correct side of the margin or within an acceptable error range. \(\:C\) is the penalty parameter. \(\:\theta\:\) denotes the offset of the hyperplane from the origin, and \(\:{y}_{i}\) is the label of the training data. The function \(\:\varnothing\:\left({x}_{i}\right)\) maps the input data \(\:{x}_{i}\) into a high-dimensional feature space, facilitating nonlinear classification.

Random forest

RF is an ensemble learning algorithm based on decision trees and is widely applied in tasks such as classification, regression, and feature selection48. The process of constructing an RF model involves several steps: First, the Bootstrap method is used to randomly sample with replacement from the original training dataset to create n new sample sets, each used to generate n decision trees. Second, at each resampling, a subset of features is randomly selected to build the decision tree. Finally, these decision trees are combined to form a “forest” (Fig. 4b). For classifying new data, the final classification is determined by the majority vote of all decision trees. RF models are highly capable of handling missing values and noisy data, and they are generally resistant to overfitting. They are also known for their robustness and accuracy when managing complex data49. Given these advantages, the RF model was chosen for this study to generate LSM for the CIALS.

LSM framework

In this study, intrinsic environmental factors and external triggering factors are calculated using ML (SVM and RF) algorithms to derive the intrinsic environmental index (IEI) and external triggering index (ETI), respectively. These indexes are used as control variables for constructing a landslide susceptibility framework based on the cusp catastrophe model (CCM) within CT50. The core task in constructing the landslide susceptibility framework is to establish the surface using the IEI, ETI and landslide susceptibility index (LSI). The correspondence between the equilibrium surface \(\:\left({x}_{1},{y}_{1},{y}_{2}\right)\) of the CCM and the surface \(\:\left(LSI,IEI,ETI\right)\) is determined through a coordinate transformation. This transformation ensures that the function with LSI, IEI and ETI meets the conditions of the cusp mutation type. Finally, based on the property that the mutations of CCM should occur in the cusp-shaped folding zone, the landslide susceptibility assessment formula is derived. The specific steps for constructing the framework are as follows:

Equation of the equilibrium surface

To accurately simulate the relationship between the control variables IEI and ETI and the state variable LSI, an equilibrium surface equation is established, referring to the equilibrium surface \(\:\left({x}_{1},{y}_{1},{y}_{2}\right)\) as determined by the CCM. The equation of the equilibrium surface is as follows:

In Eq. (2), all coefficients are non-zero constants. Let \(\:{x}_{1}={x}_{0}\) be a fixed value, then \(\:{y}_{1}\) and \(\:{y}_{2}\) exhibit a linear relationship, and the equilibrium surface consists of straight lines parallel to the \(\:{y}_{1}o{y}_{2}\) plane. As shown in Fig. 4c, \(\:{y}_{2}\) has a positive correlation with \(\:{x}_{1}\); however, when \(\:{y}_{2}\) reaches a certain range, a slight increase in \(\:{y}_{2}\) causes a sharp and discontinuous rise in \(\:{x}_{1}\).

Coordinate conversion of the equilibrium surface

In this study, let the spatial translation amount of equilibrium surface \(\:\left({x}_{1},{y}_{1},{y}_{2}\right)\) to \(\:\left(LSI,IEI,ETI\right)\) is denoted as \(\:\left({x}_{11},{y}_{11},{y}_{22}\right)\), and the rotation angle around the LSI-axis is \(\:\beta\:\), the transformation formula is given by:

According to Fig. 4c and Eq. (3), it is evident that the origin coordinates \(\:\left({x}_{11},{y}_{11},{y}_{22}\right)\) of the equilibrium surface \(\:\left(LSI,IEI,ETI\right)\) are on the equilibrium surface \(\:\left({x}_{1},{y}_{1},{y}_{2}\right)\). Therefore, the following equation holds:

Let \(\:a{x}_{11}^{3}+b{x}_{11}{y}_{1}={y}_{2}\) represent the IEI-axis. This line serves as the intersection between the plane passing through the origin of the new coordinate system and the equilibrium surface \(\:\left({x}_{1},{y}_{1},{y}_{2}\right)\). The new coordinate system is obtained by translating the original system and rotating by \(\:\beta\:\) degrees around the LSI-axis. Thus, the following equation applies:

New coordinate system

Perform peak analysis on IEI and ETI to obtain the mutation points \(\:{IEI}_{1}\), \(\:{IEI}_{2}\), \(\:{ETI}_{1}\), and \(\:{ETI}_{2}\). Since \(\:\left({LSI}_{1},{IEI}_{1},{ETI}_{1}\right)\) is the critical point where landslide susceptibility undergoes a mutation, and the origin of the coordinate system \(\:\left({x}_{1},{y}_{1},{y}_{2}\right)\) is also a critical point where a mutation exists. Therefore, for the point \(\:\left({LSI}_{1},{IEI}_{1},{ETI}_{1}\right)\) in the new coordinate system \(\:\left(LSI,IEI,ETI\right)\), make a plane perpendicular to the IEI-axis. This plane also passes through the origin of the coordinate system \(\:\left({x}_{1},{y}_{1},{y}_{2}\right)\). Then the mutation point \(\:\left({LSI}_{1},{IEI}_{1},{ETI}_{1}\right)\) in the coordinate system \(\:\left({x}_{1},{y}_{1},{y}_{2}\right)\) is \(\:\left({LSI}_{1}+{x}_{11},{ETI}_{1}sin\beta\:+{IEI}_{1}cos\beta\:+{y}_{11},{ETI}_{1}cos\beta\:-{IEI}_{1}sin\beta\:+{y}_{22}\right)\), and the direction vector of the LSI-axis is\(\:\left(0,cos\beta\:,sin\beta\:\right)\). Therefore, the equation of this plane is:

Substitute the mutation point\(({LSI}_{1}+{x}_{11},{ETI}_{1}sin\beta\:+{IEI}_{1}cos\beta\:+{y}_{11},{ETI}_{1}cos\beta\)\(-{IEI}_{1}sin\beta\:+{y}_{22})\) into Eq. (6), and solve it simultaneously with Eq. (5) to obtain:

In the coordinate system \(\:\left(LSI,IEI,ETI\right)\), a mutation will occur again at the point \(\:\left({LSI}_{2},{IEI}_{2},{ETI}_{2}\right)\), that is, point P in Fig. 4c. The coordinate point P\(({LSI}_{2}+{x}_{11},{ETI}_{2}sin\beta\) \(+{IEI}_{2}cos\beta\:+{y}_{11},{ETI}_{2}cos\beta\:-{IEI}_{2}sin\beta\:+{y}_{22})\) is the intersection and mutation point of the \(\:ETI\)-axis and the singular point set of the equilibrium surface. Therefore, there exist three roots (\(\:{x}_{11}\), \(\:{x}_{12}\) and \(\:{x}_{13}\)) for the equation \(\:{ETI}_{2}cos\beta\:-{IEI}_{2}sin\beta\:+{y}_{22}=a{x}_{1}^{3}+b{x}_{1}\left({ETI}_{2}sin\beta\:+{IEI}_{2}cos\beta\:+{y}_{11}\right)\), where two roots are equal \(\:\left({x}_{11}={x}_{13}\right)\), and satisfy the equation \(\:\left({x}_{1}-{x}_{11}\right)\left({x}_{1}-{x}_{12}\right)\left({x}_{1}-{x}_{13}\right)=0\). Solving this equation gives:

Set the coefficients of Eq. (8) equal to those of \({ETI}_{2}cos\beta\:-{IEI}_{2}sin\beta\) \(+{y}_{22}=a{x}_{1}^{3}+b{x}_{1}\left({ETI}_{2}sin\beta\:+{IEI}_{2}cos\beta\:+{y}_{11}\right)\), and substitute Eq. (5) to obtain the following equation:

Since landslide susceptibility gradually increases as the control variable coefficients increase within a certain range around point P, a transition in susceptibility occurs at point P. The magnitude of the transition from \(\:{x}_{11}\) to \(\:{x}_{12}\) is given by:

Landslide susceptibility assessment formula

By solving Eqs. (5), (3) and (2), obtain the expression of the new equilibrium surface \(\:\left(LSI,IEI,ETI\right)\). And through the Cardano formula, obtain the landslide susceptibility assessment formula established:

Parameter solving

-

(1)

Assign a random non-zero constant to \(\:b\), and use Eqs. (7), (9), and (10) to calculate the remaining 5 parameters \(\:\left(a,b,{x}_{11},{x}_{12},{y}_{11},{y}_{22}\right)\).

-

(2)

Using the 6 initially determined coefficients, derive the bifurcation curve equation \(\:\left({o}_{1}{m}_{1},{o}_{1}{n}_{1}\right)\). The equations for curves \(\:{o}_{1}{m}_{1}\) and \(\:{o}_{1}{n}_{1}\) are provided by Eqs. (12) and (13).

-

(3)

If more than 90% of the validating datasets lies outside the bifurcation curve \(\:\left({o}_{1}{m}_{1},{o}_{1}{n}_{1}\right)\), then the chosen value of \(\:b\) satisfies the solution requirements.

According to the distribution of IEI and ETI values, their mutation positions are identified through peak analysis (Fig. 5a,b). Following the parameter solution steps, it is observed that as the absolute value of \(\:b\) increases, the absolute values of \(\:a\), \(\:{y}_{11}\), and \(\:{y}_{22}\) initially rise, then decline, and eventually stabilize, while the values of \(\:{x}_{11}\) and \(\:{x}_{12}\) remain constant (Fig. 5c). When more than 90% of the landslide verification datasets are located far from the bifurcation curve, the range of acceptable values for \(\:b\) can be established (Fig. 5d). Furthermore, since the origin coordinates lie on the initial equilibrium surface, the parameters \(\:{x}_{11}\), \(\:{y}_{11}\), and \(\:{y}_{22}\) also satisfy Eq. (4). Consequently, the final value of \(\:b\) can be determined (Fig. 5e), allowing for the calculation of other parameter values for the landslide susceptibility framework (RF-CT and SVM-CT).

Verification and comparison

The ROC curve is a graphical representation of sensitivity, widely used in various fields, including LSM51,52. In the ROC curve, the Area under the curve (AUC) quantifies the uncertainty of model predictions while accounting for detection bias. This study utilizes the ROC curve, along with the spatial distribution of historical landslide datasets, to validate the results of the LSM.

This study utilize training and validating datasets to assess the framework’s performance. The training dataset is used to calculate the success rate, while the validating dataset assesses the prediction rate. Additionally, separate SVM and RF models are employed to generate landslide susceptibility maps based on landslide conditioning factors, enabling a comparative analysis with the framework developed in this study.

Result

Landslide susceptibility mapping

By substituting the IEI, ETI, and framework parameters into Eq. (11), we can derive the LSI for the CIALS. The natural breaks method categorizes the LSI into 5 classifications: Very Low, Low, Moderate, High, and Very High (Fig. 6). As illustrated in Fig. 7, the area classified as the Very high susceptibility zone is 644.57 km², representing 8.28% of the total area. The High susceptibility zone covers 1337.66 km², accounting for 17.19%. These two categories are primarily located in Ningnan County, in the southern part of the CIALS, as well as along the Jinsha River and its tributary valleys. The Moderate susceptibility zone spans 1937.16 km² (24.89%), the Low susceptibility zone covers 2342.62 km² (30.10%), and the Very low susceptibility zone encompasses 1520.37 km² (19.54%). These three categories are mainly found in mountainous areas with abundant vegetation, situated far from human activities. Overall, the spatial distribution patterns of the landslide susceptibility maps generated by the four methods are relatively consistent.

Model verification

According to the verification results of the ROC curve (Fig. 8), the LSM obtained using RF-CT shows the highest average success rate, with an AUC value of 0.899 and the lowest average standard error of 0.014. It also achieves the highest average prediction rate (AUC = 0.783) along with the lowest average standard error of 0.068. Overall, the LSMs derived from the four methods demonstrate relatively high accuracy. The average mapping success rates, from highest to lowest, are: RF-CT (0.899), SVM-CT (0.873), RF (0.761), and SVM (0.758). Similarly, the average prediction rates, from highest to lowest, are: RF-CT (0.783), SVM-CT (0.775), SVM (0.737), and RF (0.733). Notably, the average success rates of RF-CT and SVM-CT are approximately 10% higher than those of RF and SVM, while the average prediction rates exceed those of RF and SVM by about 5%.

Discussion

Accuracy analysis

The RF, SVM, RF-CT, and SVM-CT models are compared based on the generated LSMs. Qualitatively, the overall spatial distribution of Very high and High susceptibility zones shows a strong correlation with historical landslide locations. For a typical area (Fig. 6), while most landslides are concentrated in Very high and High susceptibility zones, the RF-CT and SVM-CT models generate smaller Very high and High susceptibility zones, and offering more detailed descriptions. Quantitatively, the average area of the classification categorizes of the 10 results was analyzed. The proportion of historical landslides in Very low and Low susceptibility zones for RF-CT and SVM-CT is 7.64% and 8.49%, respectively—significantly lower than 12.95% for RF and 16.77% for SVM. In Very high and High susceptibility zones, historical landslides account for 75.37% in RF-CT, 71.55% in SVM-CT, 67.30% in RF, and 63.69% in SVM. Similarly, the landslide density is higher for RF-CT (0.18 per km²) and SVM-CT (0.17 per km²) than for RF and SVM (both 0.16 per km²) in Very high and High susceptibility zones. Both qualitative and quantitative analyses show that RF-CT and SVM-CT outperform RF and SVM.

As shown in Fig. 7, regardless of the changes in the training and validating datasets, the changes in landslide susceptibility categories for RF-CT and SVM-CT are significantly smaller than those for the RF and SVM models. Figure 8c,d further confirms this result. From the training dataset, within the 95% confidence interval, there are significant differences in the AUC value ranges of the 10 sample groups. Specifically, the AUC value ranges for RF, SVM, RF-CT, and SVM-CT are 0.724–0.796 (range difference of 0.072), 0.723–0.792 (0.069), 0.879–0.918 (0.039), and 0.846–0.895 (0.049), respectively. On the validating dataset, the AUC values for RF, SVM, RF-CT, and SVM-CT range from 0.698 to 0.768 (0.070), 0.700-0.775 (0.075), 0.749–0.817 (0.061), and 0.745–0.806 (0.068), respectively. Regarding the change in AUC value ranges, on the training dataset, the AUC range for RF-CT is 45% narrower than that for RF, and for SVM-CT, it is 29% narrower than that for SVM. On the validating dataset, the AUC range for RF-CT is 11% narrower than that for RF, and for SVM-CT, it is 10% narrower than that for SVM.

These results indicate that integrating CT into RF- and SVM-based LSM models is not only feasible but also significantly improves the accuracy, stability and generalization of landslide susceptibility predictions.

The roles of RF, SVM and CT in the new framework

Existing studies indicate that hybrid and integrated ML algorithms enhance the accuracy of LSM16,53,54,55. The LSM framework developed in this study exhibits this characteristic, demonstrating significantly better performance than individual RF and SVM models. Although the mapping accuracy of RF is slightly higher than that of SVM, this aligns with current research findings56,57.

The integration of CT with RF and SVM offers a more robust prediction framework for assessing landslide occurrence probabilities. First, based on CT characteristics, conditional factors are categorized into internal environmental factors and external triggering factors, which are comprehensively analyzed by RF or SVM. This approach mitigates the uncertainties associated with traditional CT application methods (Catastrophe fuzzy membership functions, CFMFs) when determining the relative importance of conditional factors58. Second, RF’s inherent randomness reduces correlations among trees59, while SVM maximizes the margin between samples and the decision boundary60, addressing the dependency of CFMFs on the independence of conditional factors. Third, while RF generally lacks high generalization capability, the combined application of CT and RF enhances model training stability across different areas by stabilizing critical points using three variables61. Additionally, SVM can be resource-intensive when handling large datasets62, and categorizing factors into internal environmental factors and external triggering factors can improve SVM training efficiency.

In summary, landslide occurrence is a highly complex nonlinear process influenced by multiple environmental factors. SVM and RF are effective in addressing this complexity, while CT reveals the mutation characteristics of the process. CT provides a rational and mathematical framework that enables the integration of SVM and RF output results with historical landslide data (validating dataset) to identify the “mutation point” of landslide occurrence, thus deriving a landslide susceptibility assessment formula. This integration results in a more reliable and robust LSM technique compared to using SVM or RF alone. In addition, most LSMs rely on model parameter tuning, which often leads to strong performance in some regions but poor results in others63. This study uses 10 different random sample datasets to demonstrate that the proposed framework not only ensures high accuracy in LSMs but also offers stability, making it a universal model applicable to any area with relevant conditioning factors and historical landslide inventory data.

The limitations of the new framework

Although the new framework demonstrates “superior” performance, it also has certain limitations. First, to ensure that all data transition at point P during the framework construction, we selected the maximum value across all assessment units when setting the transition amount from \(\:{x}_{11}\) to \(\:{x}_{12}\) (Eq. 10), without considering the spatial characteristics, as the control variable is spatial data. Second, the conditioning factors form the basis of LSM, and any bias in these factors can affect the LSM results. For instance, the spatial interpolation method was used to convert annual precipitation data from meteorological stations into raster data. This method assumes that points closer in space are more likely to share similar characteristics50. However, using known point data to estimate unknown point data can affect the accuracy of LSM. Finally, when selecting conditional factors, we overlooked certain factors that are difficult to quantify or collect. For example, we did not account for the impact of policies, management, and prevention measures on landslide susceptibility.

Conclusions

In this study, we developed a new framework for predicting landslide occurrence probability by integrating RF, SVM, and CT. A typical area (CIALS) was selected for landslide susceptibility predicting, verification, and comparative analysis. The main conclusions are as follows:

-

(1)

Feasibility of CT integration: Introducing CT in conjunction with RF and SVM for LSM is effective. Both RF-CT and SVM-CT demonstrate excellent mapping performance, with success rates approximately 10% higher and prediction rates about 5% higher than those of RF and SVM.

-

(2)

Spatial distribution of susceptibility zones: In CIALS, the Very high susceptibility zone covers 644.57 km² (8.28% of the total area), the High susceptibility zone spans 1337.66 km² (17.19%), the Moderate susceptibility zone encompasses 1937.16 km² (24.89%), the low susceptibility zone is 2342.62 km² (30.10%), and the Very low susceptibility zone covers 1520.37 km² (19.54%). The spatial distribution patterns of landslide susceptibility derived from RF, SVM, RF-CT, and SVM-CT are relatively consistent and strongly correlate with the distribution of historical landslides.

-

(3)

Practical Implications: The research findings provide valuable references for disaster managers, poverty alleviation workers, and decision-makers in the CIALS. Governments and relevant organizations can utilize these results to avoid developing or conducting geological investigations in areas at risk of landslides. This proactive approach is one of the most effective strategies for reducing future losses of life and property, alleviating poverty, and enhancing sustainability.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are provided in Table 1 of the main text. The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Xu, Q. et al. Remote sensing for landslide investigations: A progress report from China. Eng. Geol. 321, 107156 (2023).

Casagli, N., Intrieri, E., Tofani, V., Gigli, G. & Raspini, F. Landslide detection, monitoring and prediction with remote-sensing techniques. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 4 (1), 51–64 (2023).

Deng, X., Zeng, M., Xu, D. & Qi, Y. Why do landslides impact farmland abandonment? Evidence from hilly and mountainous areas of rural China. Nat. Hazards. 113 (1), 699–718 (2022).

Zhang, S. et al. Fatal landslides in China from 1940 to 2020: Occurrences and vulnerabilities. Landslides 20 (6), 1243–1264 (2023).

Xiao, S. et al. Landslide damming threats along the Jinsha River, China. Engineering, (2024).

Shrestha, M., Noppradit, P., Shrestha, R. P. & Dahal, R. K. Understanding livelihood insecurity due to landslides in the mid-hill of Nepal: A case study of Bahrabise Municipality. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 104, 104399 (2024).

Sun, X. et al. A novel landslide susceptibility optimization framework to assess landslide occurrence probability at the regional scale for environmental management. J. Environ. Manage. 322, 116108 (2022).

Loche, M., Alvioli, M., Marchesini, I., Bakka, H. & Lombardo, L. Landslide susceptibility maps of Italy: Lesson learnt from dealing with multiple landslide types and the uneven spatial distribution of the national inventory. Earth Sci. Rev. 232, 104125 (2022).

Sonker, I. & Tripathi, J. N. Remote sensing and GIS-based landslide susceptibility mapping using frequency ratio method in Sikkim Himalaya. Quat. Sci. Adv. 8, 100067 (2022).

Patil, A. S. & Panhalkar, S. S. Remote sensing and GIS-based landslide susceptibility mapping using LNRF method in part of western ghats of India. Quat. Sci. Adv. 11, 100095 (2023).

Hodasová, K. & Bednarik, M. Effect of using various weighting methods in a process of landslide susceptibility assessment. Nat. Hazards. 105, 481–499 (2021).

Nhu, V. H. et al. Comparison of support vector machine, bayesian logistic regression, and alternating decision tree algorithms for shallow landslide susceptibility mapping along a mountainous road in the west of Iran. Appl. Sci. 10 (15), 5047 (2020).

Ngo, P. T. T. et al. Evaluation of deep learning algorithms for national scale landslide susceptibility mapping of Iran. Geosci. Front. 12 (2), 505–519 (2021).

Youssef, A. M. & Pourghasemi, H. R. Landslide susceptibility mapping using machine learning algorithms and comparison of their performance at Abha Basin, Asir Region, Saudi Arabia. Geosci. Front. 12 (2), 639–655 (2021).

Zhang, J. et al. Insights into geospatial heterogeneity of landslide susceptibility based on the SHAP-XGBoost model. J. Environ. Manage. 332, 117357 (2023).

Chen, Y., Ming, D., Ling, X., Lv, X. & Zhou, C. Landslide susceptibility mapping using feature fusion-based CPCNN-ML in Lantau Island, Hong Kong. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Observations Remote Sens. 14, 3625–3639 (2021).

Ado, M. et al. Landslide susceptibility mapping using machine learning: A literature survey. Remote Sens. 14 (13), 3029 (2022).

Ma, J. et al. Automated machine learning-based landslide susceptibility mapping for the three gorges reservoir area, China. Math. Geosci. 56 (5), 975–1010 (2024).

Huang, Y. & Zhao, L. Review on landslide susceptibility mapping using support vector machines. Catena 165, 520–529 (2018).

Arabameri, A., Pradhan, B., Rezaei, K. & Lee, C. W. Assessment of landslide susceptibility using statistical-and artificial intelligence-based FR–RF integrated model and multiresolution DEMs. Remote Sens. 11 (9), 999 (2019).

Sun, X. et al. Tracking sustainable development in mining towns: A novel framework integrating socioeconomic and eco-environmental perspectives through coupling coordination degree. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 109, 107641 (2024).

Chen, H. T., He, J., Wang, W. C. & Chen, X. N. Simulation of maize drought degree in Xi’an City based on cusp catastrophe model. Water Sci. Eng. 14 (1), 28–35 (2021).

Singh, L. K., Jha, M. K. & Chowdary, V. M. Assessing the accuracy of GIS-based multi-criteria decision analysis approaches for mapping groundwater potential. Ecol. Ind. 91, 24–37 (2018).

Wang, Y., Wang, Y., Su, X., Qi, L. & Liu, M. Evaluation of the comprehensive carrying capacity of interprovincial water resources in China and the spatial effect. J. Hydrol. 575, 794–809 (2019).

Ziarh, G. F., Asaduzzaman, M., Dewan, A., Nashwan, M. S. & Shahid, S. Integration of catastrophe and entropy theories for flood risk mapping in peninsular Malaysia. J. Flood Risk Manag. 14 (1), e12686 (2021).

Sun, X. F. et al. Spatiotemporal change of vegetation coverage recovery and its driving factors in the Wenchuan earthquake-hit areas. J. Mt. Sci. 18 (11), 2854–2869 (2021a).

Pellicone, G., Caloiero, T., Modica, G. & Guagliardi, I. Application of several spatial interpolation techniques to monthly rainfall data in the Calabria region (southern Italy). Int. J. Climatol. 38 (9), 3651–3666 (2018).

Bagan, H. & Yamagata, Y. Analysis of urban growth and estimating population density using satellite images of nighttime lights and land-use and population data. GIScience Remote Sens. 52(6), 765–780 (2015).

Lacroix, P., Handwerger, A. L. & Bièvre, G. Life and death of slow-moving landslides. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 1 (8), 404–419 (2020).

Vakhshoori, V. & Zare, M. Is the ROC curve a reliable tool to compare the validity of landslide susceptibility maps? Geomatics Nat. Hazards Risk. 9 (1), 249–266 (2018).

Chowdhuri, I. et al. Ensemble approach to develop landslide susceptibility map in landslide dominated Sikkim Himalayan region, India. Environ. Earth Sci. 79, 1–28 (2020).

Di Napoli, M. et al. Machine learning ensemble modelling as a tool to improve landslide susceptibility mapping reliability. Landslides 17 (8), 1897–1914 (2020).

Agboola, G., Beni, L. H., Elbayoumi, T. & Thompson, G. Optimizing landslide susceptibility mapping using machine learning and geospatial techniques. Ecol. Inf. 81, 102583 (2024).

Li, L. et al. A modified frequency ratio method for landslide susceptibility assessment. Landslides 14, 727–741 (2017).

Nakileza, B. R. & Nedala, S. Topographic influence on landslides characteristics and implication for risk management in upper Manafwa catchment. Mt. Elgon Uganda Geoenviron. Disasters. 7, 1–13 (2020).

Intrieri, E., Carlà, T. & Gigli, G. Forecasting the time of failure of landslides at slope-scale: A literature review. Earth Sci. Rev. 193, 333–349 (2019).

Cellek, S. The effect of aspect on landslide and its relationship with other parameters. In Landslides. IntechOpen (2021).

Ohlmacher, G. C. Plan curvature and landslide probability in regions dominated by earth flows and earth slides. Eng. Geol. 91 (2–4), 117–134 (2007).

Henriques, C., Zêzere, J. L. & Marques, F. The role of the lithological setting on the landslide pattern and distribution. Eng. Geol. 189, 17–31 (2015).

Qin, Y. et al. Spatial distribution of near-fault landslides along Litang fault zones, eastern tibetan Plateau. Geomorphology 455, 109189 (2024).

Zou, Y. et al. Factors controlling the spatial distribution of coseismic landslides triggered by the mw 6.1 Ludian earthquake in China. Eng. Geol. 296, 106477 (2022).

Sun, H. et al. Influence of spatial heterogeneity on landslide susceptibility in the transboundary area of the Himalayas. Geomorphology 433, 108723 (2023).

Shi, Y., Zhang, Z., Xue, C. & Feng, Y. Machine learning prediction of Co-seismic Landslide with Distance and Azimuth instead of Peak Ground Acceleration. Sustainability 16 (19), 8332 (2024).

Kirschbaum, D., Kapnick, S. B., Stanley, T. & Pascale, S. Changes in extreme precipitation and landslides over high mountain Asia. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47(4), e2019GL085347 (2020).

Pourghasemi, H. R., Moradi, H. R. & Fatemi Aghda, S. M. Landslide susceptibility mapping by binary logistic regression, analytical hierarchy process, and statistical index models and assessment of their performances. Nat. Hazards. 69, 749–779 (2013).

Li, Y., Wang, X. & Mao, H. Influence of human activity on landslide susceptibility development in the three gorges area. Nat. Hazards. 104, 2115–2151 (2020).

Abdullah, D. M. & Abdulazeez, A. M. Machine learning applications based on SVM classification a review. Qubahan Acad. J. 1 (2), 81–90 (2021).

Izquierdo-Verdiguier, E. & Zurita-Milla, R. An evaluation of guided regularized Random Forest for classification and regression tasks in remote sensing. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 88, 102051 (2020).

Shirvani, Z. A holistic analysis for landslide susceptibility mapping applying geographic object-based random forest: A comparison between protected and non-protected forests. Remote Sens. 12 (3), 434 (2020).

Sun, X. et al. Integrated decision-making model for groundwater potential evaluation in mining areas using the cusp catastrophe model and principal component analysis. J. Hydrology: Reg. Stud. 37, 100891 (2021).

Cantarino, I., Carrion, M. A., Goerlich, F. & Martinez Ibañez, V. A ROC analysis-based classification method for landslide susceptibility maps. Landslides 16, 265–282 (2019).

Wang, Y. et al. Utilizing deep learning approach to develop landslide susceptibility mapping considering landslide types. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 83 (11), 1–19 (2024).

Pham, B. T., Bui, D. T., Prakash, I. & Dholakia, M. B. Hybrid integration of Multilayer Perceptron neural networks and machine learning ensembles for landslide susceptibility assessment at Himalayan area (India) using GIS. Catena 149, 52–63 (2017).

Fang, Z., Wang, Y., Peng, L. & Hong, H. Integration of convolutional neural network and conventional machine learning classifiers for landslide susceptibility mapping. Comput. Geosci. 139, 104470 (2020).

Elkhrachy, I. et al. Landslide susceptibility mapping and management in Western Serbia: An analysis of ANFIS-and SVM-based hybrid models. Front. Environ. Sci. 11, 1218954 (2023).

Agrawal, N. & Dixit, J. GIS-based landslide susceptibility mapping of the Meghalaya-Shillong Plateau region using machine learning algorithms. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 82 (5), 170 (2023).

Miao, F. et al. Landslide dynamic susceptibility mapping base on machine learning and the PS-InSAR Coupling Model. Remote Sens. 15 (22), 5427 (2023).

Kaur, L., Rishi, M. S., Singh, G. & Thakur, S. N. Groundwater potential assessment of an alluvial aquifer in Yamuna sub-basin (Panipat region) using remote sensing and GIS techniques in conjunction with analytical hierarchy process (AHP) and catastrophe theory (CT). Ecol. Ind. 110, 105850 (2020).

Hu, J. & Szymczak, S. A review on longitudinal data analysis with random forest. Brief. Bioinform. 24 (2), bbad002 (2023).

Pisner, D. A. & Schnyer, D. M. Support vector machine. In Machine Learning (eds Pisner, D. A. & Schnyer, D. M.) 101–121 (Academic, 2020).

Papacharalampous, A. E. & Vlahogianni, E. I. Modeling microscopic freeway traffic using cusp catastrophe theory. IEEE Intell. Transp. Syst. Mag. 6 (1), 6–16 (2014).

Gaye, B., Zhang, D. & Wulamu, A. Improvement of support vector machine algorithm in big data background. Math. Probl. Eng. 2021 (1), 5594899 (2021).

Sun, D., Xu, J., Wen, H. & Wang, D. Assessment of landslide susceptibility mapping based on bayesian hyperparameter optimization: A comparison between logistic regression and random forest. Eng. Geol. 281, 105972 (2021).

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42401387), Department of Science and Technology of Sichuan Province (2020YFS0530), and Natural Science Foundation of Sichuan Province (2024NSFSC0786).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.Z. and Y.Z. are co-first authors of the article. Conceptualization, W.Z., Y.Z. and S.L; methodology, W.Z. and Y.Z.; software, W.Z. and S.L.; validation, W.Z. and Y.Z.; formal analysis, Y.Z.; investigation, W.Z. and Y.Z.; data curation, W.Z.; writing— original draft preparation, Y.Z.; writing—review and editing, W.Z., Y.Z., X.S. and H.D.; visualization, Y.Z.; supervision, X.S. and S.L; funding acquisition, X.S. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, W., Zhou, Y., Liang, S. et al. A new framework for landslide susceptibility mapping in contiguous impoverished areas using machine learning and catastrophe theory. Sci Rep 15, 10620 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88070-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88070-9

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Assessing landslide susceptibility mapping in the Sikkim Himalayas using an ensemble machine learning approach

Discover Geoscience (2026)

-

Decoding Landslide Susceptibility in Wayanad District of Kerala, India, Using Machine Learning Approach

Earth Systems and Environment (2025)

-

Assessing Consistency and Inconsistency in Landslide Susceptibility Mapping: Quality Criteria and Pixel-Level Analysis in a Case Study from the Alborz Mountains, North of Tehran, Iran

Natural Hazards (2025)