Abstract

Lipocalin-2 (LCN2) has three main variants; polyaminated (hLCN2) and non-polyaminated (C87A and R81E). The polyaminated form is proposed to positively influence energy control, whereas the non-polyaminated forms negatively impact energy control in mice. Glucocorticoids negatively affect glucose regulation and exercise has a positive effect. We hypothesise that glucocorticoids will suppress, while exercise will increase hLCN2, and decrease C87A and R81E, which will be associated with improved insulin sensitivity. In a randomised crossover design, nine young healthy men (aged 27.8 ± 4.9 years; BMI 24.4 ± 2.4 kg/m2) completed 30 min of high-intensity aerobic exercise (90–95% heart rate reserve) after glucocorticoid or placebo ingestion. Blood was collected and analyzed for LCN2 and its variants levels at baseline, immediately, 60 min and 180 min post-exercise. Insulin sensitivity was assessed using hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp. A main effect, increase in LCN2 was detected for prednisolone ingestion (overall treatment effect p = 0.001), but not LCN2 variants (all p > 0.05). Main effects for time were observed for exercise for LCN2 and all variants (overall time effect all p < 0.02). Regardless of treatment, LCN2, C87A, R81E, and hLCN2 increased immediately after exercise compared with baseline (all p < 0.04). C87A, but not LCN2 or its other variants, remained elevated at 180 min post-ex (p = 0.007). LCN2, but not its variants, was elevated in response to prednisolone ingestion. LCN2 and its variants are transiently increased by acute exercise, but this increase was not related to insulin sensitivity. The clinical implication of elevated LCN2 and its variants post-exercise on satiety and energy regulation, as well as the mechanisms involved warrant further investigation.

Clinical trial registration: www.anzctr.org.au, ACTRN12615000755538.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Lipocalin-2 (LCN2), also known as neutrophil gelatinase–associated lipocalin, is an important protein for satiety and energy regulation that is implicated in bone-muscle-fat interaction. It is expressed by multiple cell-types including adipocytes, osteoblasts, and renal tubular cells1. Circulating LCN2 is an established marker of kidney injury2 and more recently, it has also been suggested as a marker of cardio-metabolic disease independent of kidney disease3. Chronically elevated circulating LCN2 levels are associated with cardio-metabolic diseases related to impaired insulin sensitivity such as diabetes, obesity, and metabolic syndrome4,5. Other models of insulin resistance, such as glucocorticoid treatment6, can also lead to the upregulation of LCN2 in chondrocyte and adipocyte human primary cells7,8. Secretion of LCN2 is known to be upregulated in adipose tissue in pathological states, such as type 2 diabetes, though its exact role and mechanisms remain unclear9. As such, LCN2 has been positioned as a negative regulator of energy homeostasis and a contributor to insulin resistance.

Despite the link between increased circulating levels of LCN2 and cardio-metabolic disease, findings are not always consistent. Increased LCN2 does not always have negative consequences. For example, bone-derived LCN2 may suppress appetite and improve energy metabolism1. Similarly, acute exercise leads to a transient increase in circulating LCN210,11, yet acute exercise and muscle contraction are well-known to stimulate glucose uptake and increase insulin sensitivity for up to 24–48 h following exercise12. As such, LCN2 may also be integral to maintaining energy homeostasis and insulin sensitivity.

It is possible that some of the inconsistencies surrounding the role of LCN2 in cardio-metabolic risk are driven by differential expression of LCN2 in multiple tissue types. This has led to the identification of three variants in humans. The hLCN2 variant (polyaminated) is secreted by osteoblasts and has a positive effect on glucose regulation and appetite, and the C87A (non-polyaminated form) and R81E (altered ligand binding) are secreted by adipocytes and have a negative effect on glucose regulation1,3. It is suggested that polyamination of the protein promotes its clearance from circulation and is linked to positive health outcomes whereas in pathological cardio-metabolic states, non-polyaminated LCN2 levels are increased13. Yet how these forms respond to pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatments in humans is not clear.

Glucocorticoids are known to have a global effect on metabolism and inflammation. Insulin sensitivity is reduced systemically and locally at the liver, muscle and adipose in response to glucocorticoid use14. Insulin resistance stimulated by glucocorticoid use was previously shown to be moderated by osteoblast-derived hormones in mice15. We previously reported that glucocorticoids can be used to induce a state of acute insulin resistance and examine the link between glucose regulation and bone-muscle-fat interaction in humans. Specifically, undercarboxylated osteocalcin, another hormone implicated in bone-muscle-fat interaction, was decreased at rest and following high-intensity exercise in response to glucocorticoid ingestion in healthy males16. Whether other hormones released by bone, such as LCN2, are involved in glucose regulation is not yet clear. This information will help us to elucidate whether LCN2 is a modifiable factor involved in cardio-metabolic risk.

The primary aim of this study was to investigate whether LCN2 and its variants are acutely modified by glucocorticoid ingestion (an acute model of insulin resistance) and aerobic exercise (an acute model of enhanced insulin sensitivity). The secondary aim was to determine whether LCN2 variant ratios are acutely modified in response to glucocorticoid ingestion and aerobic exercise. As glucocorticoids (negatively) and exercise (positively) affect osteoblast function, we hypothesise that glucocorticoids will suppress circulating levels of hLCN2, while exercise following glucocorticoids will increase hLCN2 and decrease C87A and R81E levels, which will be associated with increased insulin sensitivity.

Methods

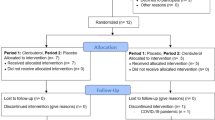

This study is a randomised crossover design, examining the effect of high-intensity exercise and prednisolone ingestion on bone-muscle-fat interaction and glucose regulation16. Nine healthy, young adult men were recruited from the general population. Exclusion criteria included: major disease such as medications affecting bone metabolism or insulin secretion and/or sensitivity, osteoporosis, people with metabolic diseases including diabetes and other metabolic diseases, cardiovascular diseases, chronic kidney disease, endocrine conditions such as thyroid dysfunction, musculoskeletal conditions affecting daily function and medications or supplements that may influence research outcomes such as warfarin, glucocorticoids and vitamin K supplementation. Participants provided informed consent following verbal and written communication of the study. The study was approved by the Victoria University Human Research Ethics Committee (HRE14-099) and was registered with Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (ACTRN12615000755538, registered 21/07/2015). This complied with ethical principles for medical research per the Declaration of Helsinki.

Graded exercise test

Participants completed a graded exercise test (GXT) to measure VO2peak, peak power, and peak heart rate (HR) on a cycle ergometer (Lode Excalibur Sport; Lode Medical Technology, Groningen, The Netherlands) which was used to prescribe the exercise intensity for the subsequent exercise sessions (experimental phase)16. Gas exchange was measured via indirect calorimetry (Quark CPET; Cosmed, Rome, Italy). Participants were then randomised to complete a placebo treatment session and a prednisolone treatment session, in a crossover fashion.

Experimental phase (placebo and prednisolone ingestion)

Following the screening assessments, participants completed a food diary 24 h prior to their first experimental session which they were then asked to replicate prior to their second experimental session. The full experimental protocol was reported previously17. In brief, participants ingested either a prednisolone or identical placebo capsule in a randomised order 12 h prior to visiting the laboratory at Victoria University. Participants and researchers were blinded to the intervention arm. Participants arrived after an overnight fast and completed a high-intensity interval exercise (HIIE) session on a cycle ergometer. Target heart rate during exercise was determined via the Karvonen heart rate reserve (HRR) method: (% exercise intensity × (HRpeak – HRrest)) + HRrest. The session included a six min warm-up (50–60% HRR) followed by 4 × 4 min high-intensity bouts (90–95% HRR) interspersed with 2 min of active recovery (50–60% HRR). Insulin sensitivity was assessed by a 2-hour hyperinsulinaemic-euglycaemic clamp beginning 3 h after exercise, as previously reported16. Blood glucose was assessed every 5 min using a glucose analyzer (YSI 2300 STAT Plus, YSI Inc., OH, USA). Glucose infusion rates (GIR) were calculated during steady state, defined as the last 30 min of the insulin clamp. Blood samples collected at 90 min and 120 min of the clamp were used to determine insulin for the assessment of insulin sensitivity. Participants then had a seven-day washout period before undertaking the alternative treatment (placebo or prednisolone) and completing an otherwise identical experimental session.

Blood sampling and analysis

Venous blood samples were collected from an antecubital vein via cannulation. Blood samples were collected at baseline, immediately post-exercise, 60 min and 180 min post-exercise for LCN2 analysis. Blood clotted for 10 min in serum separator vacutainers, then serum was collected after centrifugation (10 min at 3500 rpm, 4 °C) and stored at -80 oC.

Fasting blood samples were analyzed for insulin and HbA1c at Austin Health Pathology (Melbourne, Australia) following standard commercial protocols. Glucose was measured using an automated analysis system (YSI 2300 STAT Plus® Glucose & Lactate Analyser).

The levels of LCN2 in serum samples were measured using a commercially available ELISA kit (Product #ab215541, Abcam, Cambridge, UK), according to the manufacturer’s guidelines. LCN2 was analyzed at baseline, 0 min (immediately) post-exercise and 180 min post-exercise. The hLCN2, C87A and R81E variants were analyzed at the aforementioned three time points in addition to 60 min post-exercise. As previously reported, LCN2 variants were analyzed in triplicates using an in-house assay18. Immunizing New Zealand female rabbits generated polyclonal antibodies against hLcn2, C87A, or R81E which were then purified using affinity chromatography. Further detail on the method for developing the recombinant antigens for each variant was previously published4,19,20,21 Specific sandwich ELISA kits were developed for each LCN2 variant using neutralizing antibodies. In the ELISA assay, serum samples were diluted at a ratio of 1:100 and added to the coated ELISA plates along with recombinant protein standards. After incubation and washing, biotinylated antibodies specific to the LCN2 variants were performed, followed by streptavidin-conjugated horseradish peroxidase and substrates. The immune complexes formed were detected using a plate reader (BioTek Instruments Inc., Winooski, VT, USA) measuring the absorbance at 450 nm. The intra- and inter-assay variations were evaluated by measuring three different samples in ten replicates by a single assay, or in duplicate by five consecutive assays, respectively. The intra- and inter- assay CVs were 2.0–2.2%, 1.1–1.9% and 1.0–1.8% for the ELISA of hLcn2, C87A and R81E, respectively. The sensitivities of the three assays were 0.268 ng/ml, 0.202 ng/ml and 0.266 ng/ml, respectively. The ELISA spike recovery was 84.15%, 72.06% and 92.06%, for hLcn2, C87A and R81E, respectively.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics (version 29, 2022, Armonk, NY: IBM Corp), R Studio version 4.3.0 and GraphPad Prism statistical analysis software (version 10.0.3, 2023, GraphPad, La Jolla, CA, USA). Data were analyzed for skewness and kurtosis, and histograms were visually assessed for normality. One participant had insufficient sample quality for the baseline placebo and post-exercise placebo samples for the C87A variant. These data points were confirmed statistical outliers using extreme studentized deviate test (p < 0.05) and therefore excluded. Additionally, one participant had insufficient sample quantity for analysis at the 180 min time-point for placebo and prednisolone conditions. LCN2 variant ratios were calculated as previously reported18. We used paired t-tests to compare baseline LCN2 levels, variant levels, and variant ratios in response to treatment. Linear mixed models were used to determine the effect of treatment condition (treatment; placebo and prednisolone) in response to acute exercise (time; baseline and immediately post, 60 and 180 min post-exercise) and to determine the interaction between time and treatment (between-group differences). Participant codes were used as a random effect to account for repeated measures. To determine the effect of acute exercise in each treatment condition (within-group changes), estimated marginal means were calculated from the linear mixed models. The level of significance was set at 95% (p ≤ 0.05) for statistical analyses.

Results

Nine healthy young men completed the study (age 27.8 ± 4.9 years; BMI 24.4 ± 2.4 kg/m2; VO2peak 46.1 ± 9.5 mL/kg/min; HbA1c 5.2 ± 0.2%).

Prednisolone ingestion did not significantly change the baseline levels of LCN2, any of the variants, or the ratios compared with placebo (all p > 0.05; Table 1).

Effect of prednisolone and exercise on LCN2 and LCN2 variants

Linear mixed models for LCN2 and its variants are presented in Fig. 1.

Absolute values pre- and post-exercise expressed as mean and SEM (ng/mL) for (A) LCN2 (Abcam), (B) hLCN2, (C) C87A, (D) R81E. *p < 0.05 exercise time-point significantly different compared to baseline in linear mixed model analyses. #p < 0.05 exercise time-point significantly different compared to baseline for the same condition in post-hoc analysis. &p < 0.05 exercise time-point significantly different compared to immediately post-exercise for the same condition in post-hoc analysis. No interaction effects were detected in LCN2 or its variants (all p > 0.05).

Main effects for time (p < 0.001) and treatment (p = 0.001) were detected for LCN2. Main effects for time, but not treatment, were detected for all variants: hLCN2 (p = 0.023), C87A (p < 0.001) and R81E (p = 0.002). No time by treatment interactions were observed for LCN2 and its variants (all p > 0.05). Circulating levels of LCN2, hLCN2, C87A and R81E significantly increased immediately post-exercise compared with baseline (p < 0.001, p = 0.041, p < 0.001, p = 0.012, respectively) (Fig. 1A-D). C87A was significantly elevated at 180 min post-exercise compared with baseline (p = 0.007, Fig. 1C). No significant differences were observed for LCN2, hLCN2 or R81E 180 min post-exercise compared with baseline (all p > 0.05). LCN2 and all variants were not significantly correlated with indices of glucose metabolism (fasting glucose, fasting insulin, HOMA-IR at baseline, m-value and glucose infusion rate post-exercise, all p > 0.05).

Within-groups differences are presented in Fig. 1 and in supplementary Table 1. LCN2 significantly increased post-exercise compared with baseline within both the placebo and prednisolone ingestion conditions (p < 0.001 for both), increased at 180 min post-exercise compared with baseline within the prednisolone condition (p = 0.048), and decreased at 180 min post-exercise compared with immediately post-exercise within both placebo and prednisolone conditions (p < 0.001 for both, Fig. 1A).

C87A was significantly increased immediately post-exercise (p = 0.004) and remained elevated 180 min post-exercise compared with baseline in the placebo condition (p = 0.033, Fig. 1C). A trend for an increase in C87A immediately post-exercise compared with baseline was observed in the prednisolone condition (p = 0.057).

LCN2 variant ratios

No significant changes were observed for hLCN2/C87A (Fig. 2A; main effect for time p = 0.140 and treatment p = 0.770), hLCN2/R81E (Fig. 2B; main effect for time p = 0.351 and treatment p = 0.682), or C87A/R81E ratios (Fig. 2C; main effect for time p = 0.186 and treatment p = 0.679).

Discussion

The present study focused on the response of LCN2 and its variants to glucocorticoid ingestion and acute exercise in young healthy men. We report that circulating LCN2 and all variants transiently increased immediately post-exercise, after which levels returned to baseline levels except for C87A which remained elevated 180 min post-exercise. Acute glucocorticoid ingestion had an overall main effect on LCN2 (elevated levels), but not its variants. The clinical importance of elevated LCN2 and its variants post-exercise, and the mechanisms involved, should be explored in future studies.

LCN2 is a protein implicated in bone-muscle-fat crosstalk and is released by multiple tissues. It is suggested that under normal physiological conditions, LCN2 is predominantly polyaminated and released by osteoblasts, whereas in pathological states expression is increased in other tissues including adipose22. Whilst it is an established marker of kidney injury, the role of LCN2 in cardio-metabolic dysfunction is less clear22. It is suggested that LCN2 may be implicated in glucose regulation and insulin sensitivity4. Higher circulating LCN2 levels are associated with increased cardio-metabolic risk and disease such as diabetes and metabolic syndrome in observational human studies4,5. However, LCN2 is suggested to be a potential regulator of insulin sensitivity and is suggested to be tissue specific1,23. LCN2 exists as multiple variants in humans including hLCN2 (polyaminated), C87A (non-polyaminated) and R81E (altered ligand-binding). A vast majority of the current literature does not differentiate between these variants, which have different pathophysiological implications. Previous work suggests hLCN2 may be associated with “normal” physiological function, whilst increased C87A and R81E may be associated with pathological processes18. This paper examines for the first time, the effect of glucocorticoids and acute exercise on LCN2 variant levels in humans.

LCN2 response to acute glucocorticoid ingestion

We previously reported increased fasting glucose, insulin and HOMA-IR in this cohort in response to acute glucocorticoid treatment, indicative of reduced insulin sensitivity16. Glucocorticoid treatment is known to reduce insulin sensitivity systemically and at the liver, muscle and adipose tissue14. In the current study, we discovered that the response of LCN2 to exercise was not altered by glucocorticoids ingestion. This was observed despite an overall elevation of LCN2 levels (but not its variants) with the administration of prednisolone. This is in contrast to previous adipose cell line experiments that found an up-regulation of LCN2 in response to glucocorticoid ingestion was significant for pre-menopausal women, but not men8. It was suggested that these sex-differences may be attributed to a role of oestrogen in the regulation of LCN2 expression from adipose tissue8. It will be important to consider the role of sex hormones in future exercise studies examining the LCN2 response. Additionally, a study in people with type 2 diabetes reported that higher circulating LCN2 levels were associated with reduced insulin sensitivity, whereas 8-weeks of treatment with the glucose lowering medication rosiglitazone decreased LCN2 levels and was linked with improved insulin sensitivity4. As such, it is possible that a greater link between LCN2 and insulin sensitivity will be seen in those with a state of chronic reduced insulin sensitivity or, in other words, those that are insulin resistant (e.g., type 2 diabetes).

LCN2 response to acute exercise

The LCN2 gene encoding LCN2 protein is a mechanoresponsive gene that is upregulated in animal and human models in response to chronic low mechanical load, such as bed-rest models24. An important finding of the current study was that LCN2 and the variants increased immediately in response to HIIE, followed by a return to levels similar to baseline in LCN2 and all variants by 180 min post-exercise. The C87A variant was an exception to this return to baseline levels, remaining significantly elevated compared to baseline at 180 min post-exercise. Previous studies reported that total serum LCN2 levels increased immediately post-acute aerobic exercise (graded exercise test, “Gran Sasso d’Italia” vertical run, 60 min moderate-intensity cycling), aligning with the post-exercise increase in the current study10,25,26. The increase in LCN2 following exercise may be important from a physiological point of view. Chronically elevated LCN2 may be related to an increased risk of cardio-metabolic diseases, but it is possible that acute increase in LCN2 and/or it variants may help facilitate glucose regulation which is critical to managing the stress of exercise. In obese animal models, LCN2 levels are proposed as a protective mechanism against the development of insulin resistance23. We previously reported a similar phenomenon for oxidative stress-mediated muscle cell signalling27. Chronic systemic oxidative stress leads to cell signalling that is associated with insulin resistance and cardio-metabolic disease27. However, these same signalling pathways are activated by acute exercise and are associated with enhanced insulin sensitivity in middle-aged obese men27. Furthermore, as is the case with chronic systemic oxidative stress which decreases with exercise training, it is possible that transient acute exposure to LCN2 (e.g. exercise) can, over time (e.g., exercise training), lead to decreased chronic systemic LCN2. An observational study reported that those who engaged in regular physical activity and those with higher energy expenditure have lower circulating levels of LCN228. This hypothesis should be tested in the future.

Whilst LCN2 increases in response to acute exercise were previously reported in both healthy weight and obese people, baseline levels were higher, and the magnitude of the increase was greater in people who are obese10. We previously reported higher BMI and fat mass were associated with increased circulating LCN2 in older women5. As LCN2 changes with acute exercise did not significantly differ following prednisolone ingestion, a state of transient insulin resistance, it is possible that exercise-mediated responses occur via metabolic pathways independent of insulin. As such, it is possible that LCN2 may play a role, at least in part, in contraction-mediated glucose uptake. It was previously reported that LCN2 levels were higher following high-glucose ingestion if exercise was performed beforehand26. This hypothesis should be tested in future studies. Given the relationships between LCN2 and fat mass, it is possible this relationship is mediated by a pathway directly related to excess adiposity, however, this is beyond the scope of the current study as our population includes healthy men with “healthy weight” BMI (mean 24.4 kg/m2).

LCN2 variants response to exercise

In humans, three LCN2 variants have been identified through their post-translational modifications (polyaminated; hLCN2, non-polyaminated; C87A, altered ligand binding; R81E)18. Interestingly, all variants of LCN2 were upregulated immediately in response to HIIE in this study. This suggests that all LCN2 variants may be translated by processes stimulated in response to acute HIIE. As LCN2 has previously been established as an inflammatory mediator29, and acute exercise is known to cause a transient inflammatory response30, these observations in the variants for the current study may be linked to its inflammatory role. Future mechanistic studies are required to confirm this link, and extend this to determine how transient acute phase responses to exercise for LCN2 variants relate to chronic responses. Bone-derived LCN2 (hLCN2) has previously been reported to play a key role in positively regulating glucose metabolism, as opposed to adipocyte-derived LCN2 (C87A and R81E). Interestingly, C87A was significantly elevated at 180 min post-exercise compared to baseline, whereas LCN2, hLCN2 and R81E returned to baseline levels. Further studies are needed to determine the cardio-metabolic implications of this acutely sustained elevation of the C87A variant.

LCN2 variant ratios response to glucocorticoid ingestion and acute exercise

hLCN2/C87A, hLCN2/R81E and C87A/R81E ratios did not significantly change in response to exercise or glucocorticoid treatment. This is the first time LCN2 variant ratios have been examined in response to exercise, and only one previous study, of observational design, reports LCN2 variant ratios18. The clinical importance of the LCN2 ratios may hold the key for early identification of people who are at risk for cardio-metabolic disease. For instance, previous studies examining cholesterol and cholesterol forms demonstrated that the ratio between the “good” cholesterol (HDL) and the “bad” cholesterol (LDL) is better at predicting cardio-metabolic risk compared with the use of each form alone31. It is possible that with LCN2 variants, like cholesterol, the proportions of the variants relative to one another may be a more useful cardio-metabolic indicator and should be investigated in larger cohorts. We previously reported all LCN2 variant ratios were significantly positively correlated with BMI, heart rate and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, and negatively correlated with adiponectin and urinary aldosterone18. It is possible that significant changes were not observed in our study as only young, healthy men were included. Therefore, further studies across different populations are needed to elucidate whether the variant ratios play a significant role in exercise-stimulated processes, as well as pathological processes.

Limitations

This study has some potential limitations. Due to invasive procedures involved in the larger study, i.e. muscle biopsies, the sample size is relatively small. As such, this study should be viewed as hypothesis generating. Based on our findings, it appears that acute exercise, and, to a lesser effect, glucocorticoid treatment, influences LCN2 levels in young, healthy males. Further studies would be needed to understand whether similar trends are observed in women and in clinical populations with chronic cardio-metabolic dysregulation as well as bone disease, such as osteoporosis. Of importance, the assays for the LCN2 variants analysis are polyclonal. It will be important to develop a monoclonal assay to improve the specificity of LCN2 variant analysis to further validate our results. Cause and effect cannot be determined in the current study due to the study design. Whilst the mechanism of LCN2 in glucose regulation and with exercise are currently unknown, previous work has found that LCN2 upregulation post acute-exercise positively correlated with Wnt pathway regulator, DKK1-1, that is implicated in glucose metabolism9,25. This potential mechanism should be explored in future studies.

Conclusion

In conclusion, acute exercise transiently increases circulating levels of LCN2 and its variants in young, healthy men. The ingestion of glucocorticoids leads to an increase in circulating LCN2, but not the variants, without affecting the exercise-induced response. This study is an important first step in uncovering the responses of LCN2 variants to exercise and pharmacological treatments which may enable us to target LCN2 in the future in clinical settings. LCN2 demonstrates potential to be used as a modifiable risk factor following exercise that may be used in clinical practice.

Data availability

Data availability: Data will be made available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author for the purposes of reproducing the results or replicating the procedures. This material will be available on request and approval of Victoria University Human Ethics Committee.

References

Mosialou, I. et al. MC4R-dependent suppression of appetite by bone-derived lipocalin 2. Nature 543 (7645), 385–390. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature21697 (2017).

Albert, C. et al. Neutrophil Gelatinase-Associated Lipocalin measured on Clinical Laboratory platforms for the prediction of Acute kidney Injury and the Associated need for Dialysis Therapy: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Am. J. Kidney Diseases: Official J. Natl. Kidney Foundation. 76 (6), 826–841e1. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2020.05.015 (2020).

Li, D., Yan Sun, W., Fu, B., Xu, A. & Wang, Y. Lipocalin-2—The myth of its expression and function. ;127(2):142–151. (2020). https://doi.org/10.1111/bcpt.13332

Wang, Y. et al. Lipocalin-2 is an inflammatory marker closely associated with obesity, insulin resistance, and hyperglycemia in humans. Clin. Chem. Jan. 53 (1), 34–41. https://doi.org/10.1373/clinchem.2006.075614 (2007).

Bauer, C. et al. Circulating lipocalin-2 and features of metabolic syndrome in community-dwelling older women: a cross-sectional study. Bone 176, 116861. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bone.2023.116861 (2023).

Li, J-X. & Cummins, C. L. Fresh insights into glucocorticoid-induced diabetes mellitus and new therapeutic directions. Nat. Reviews Endocrinol. 18 (9), 540–557. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41574-022-00683-6 (2022).

Owen, H. C., Roberts, S. J., Ahmed, S. F. & Farquharson, C. Dexamethasone-induced expression of the glucocorticoid response gene lipocalin 2 in chondrocytes. Am. J. Physiology-Endocrinology Metabolism. 294 (6), E1023–E1034. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpendo.00586.2007 (2008).

Kamble, P. G. et al. Lipocalin 2 produces insulin resistance and can be upregulated by glucocorticoids in human adipose tissue. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 427, 124–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mce.2016.03.011 (2016).

Jaberi, S. A. et al. Lipocalin-2: structure, function, distribution and role in metabolic disorders. Biomed. Pharmacother. 142, 112002. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2021.112002 (2021).

Damirchi, A., Rahmani-Nia, F. & Mehrabani, J. Lipocalin-2: response to a progressive treadmill protocol in obese and normal-weight men. Asian J. Sports Med. 2 (1), 44–50. https://doi.org/10.5812/asjsm.34821 (2011).

Wołyniec, W., Ratkowski, W., Renke, J. & Renke, M. Changes in novel AKI biomarkers after Exercise. A systematic review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21 (16). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21165673 (2020).

Cartee, G. D. Mechanisms for greater insulin-stimulated glucose uptake in normal and insulin-resistant skeletal muscle after acute exercise. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metabolism. 309 (12), E949–E959. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpendo.00416.2015 (2015).

!!! INVALID CITATION !!! [14].

Geer, E. B., Islam, J. & Buettner, C. Mechanisms of glucocorticoid-Induced insulin resistance: focus on adipose tissue function and lipid metabolism. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. North Am. 43 (1), 75–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecl.2013.10.005 (2014).

Brennan-Speranza, T. C. et al. Osteoblasts mediate the adverse effects of glucocorticoids on fuel metabolism. J. Clin. Investig. 122 (11), 4172–4189. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI63377 (2012).

Parker, L. et al. Glucocorticoid-Induced insulin resistance in men is Associated with suppressed undercarboxylated osteocalcin. ;34(1):49–58. (2019). https://doi.org/10.1002/jbmr.3574

Levinger, I. et al. A single dose of Prednisolone as a modulator of undercarboxylated osteocalcin and insulin sensitivity Post-exercise in Healthy Young men: a study protocol. JMIR Res. Protocols. 5 (2), e78. https://doi.org/10.2196/resprot.5119 (2016).

Li, D. et al. Lipocalin-2 variants and their relationship with cardio-renal risk factors. Front. Endocrinol. 12, 781763. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2021.781763 (2021).

Song, E. et al. Deamidated lipocalin-2 induces endothelial dysfunction and hypertension in dietary obese mice. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 3 (2), e000837. https://doi.org/10.1161/jaha.114.000837 (2014).

Yang, K. et al. Measuring non-polyaminated lipocalin-2 for cardiometabolic risk assessment. ESC Heart Fail. 4 (4), 563–575. https://doi.org/10.1002/ehf2.12183 (2017).

Sun, W. Y. et al. Lipocalin-2 derived from adipose tissue mediates aldosterone-induced renal injury. JCI Insight. 3 (17). https://doi.org/10.1172/jci.insight.120196 (2018).

Lin, X. et al. Roles of bone-derived hormones in type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular pathophysiology. Mol. Metab. 40, 101040. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molmet.2020.101040 (2020).

Guo, H. et al. Lipocalin-2 deficiency impairs thermogenesis and potentiates diet-induced insulin resistance in mice. Diabetes 59 (6), 1376–1385. https://doi.org/10.2337/db09-1735 (2010).

Rucci, N. et al. Lipocalin 2: a new mechanoresponding gene regulating bone homeostasis. J. Bone Min. Res. 30 (2), 357–368. https://doi.org/10.1002/jbmr.2341 (2015).

Ponzetti, M. et al. Lipocalin 2 increases after high-intensity exercise in humans and influences muscle gene expression and differentiation in mice. J. Cell. Physiol. 237 (1), 551–565. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcp.30501 (2022).

Parker, L. et al. Prior aerobic exercise mitigates the decrease in serum osteoglycin and lipocalin-2 following high-glucose mixed-nutrient meal ingestion in young men. Am. J. Physiology-Endocrinology Metabolism. 323 (3), E319–E332. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpendo.00025.2022 (2022).

Parker, L. et al. Acute High-Intensity interval Exercise-Induced Redox Signaling is Associated with enhanced insulin sensitivity in obese middle-aged men. Front. Physiol. 7, 411. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2016.00411 (2016).

Lim, W. H. et al. Circulating lipocalin 2 levels predict fracture-related hospitalizations in Elderly women: a prospective cohort study. J. bone Mineral. Research: Official J. Am. Soc. Bone Mineral. Res. 30 (11), 2078–2085. https://doi.org/10.1002/jbmr.2546 (2015).

Bhusal, A. et al. Paradoxical role of lipocalin-2 in metabolic disorders and neurological complications. Biochem. Pharmacol. 169, 113626. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bcp.2019.113626 (2019).

Pedersen, B. K. & Hoffman-Goetz, L. Exercise and the Immune System: Regulation. Integr. Adaptation. 80 (3), 1055–1081. https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.2000.80.3.1055 (2000).

Millán, J. et al. Lipoprotein ratios: physiological significance and clinical usefulness in cardiovascular prevention. Vasc. Health Risk Manag. 5, 757–765 (2009).

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The salary of MS is supported by a Career Advancement Fellowship from the Royal Perth Hospital Research Foundation and an Emerging Leader Fellowship by the Future Health Research and Innovation Fund, Department of Health (Western Australia). JRL is supported by a National Heart Foundation Future Leader Fellowship (ID: 102817). LP is supported by a NHMRC & National Heart Foundation Early Career Fellowship (GNT1157930).

Funding

This study was partially funded by IL previous heart foundation fellowship (ID: 100040).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Author contributions: Conceptualization: CB, DLH, PRE, LP, IL. Investigation: QS, HL, DK, XL, AG, YW, LP, IL. Methodology: AG, LP, IL. Formal analysis: CB, RKP, MS. Writing – original draft: CB, IL. Supervision: MW, MS, JRL, LP, IL. Project administration: LP, IL. Writing – review and editing: RKP, QS, HL, DK, MW, XL, AG, DLH, PRE, MS, JRL, YW, LP, IL. All authors reviewed and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare the following competing interests: PRE is supported by an NHMRC Investigator grant (GNT1197958). He has received research funding from Amgen, Alexion and Sanofi, and honoraria from Amgen, Alexion and Kyowa Kirin. DLH has received research funds, consultation fees, advisory board payments or educational grants from Abbott, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, CSL-Seqiris, Kaneda, Lundbeck, Merck, Novartis, Regeneron, Sanofi, Servier, and Vifor. Other authors state that they have no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bauer, C., Patten, R.K., Sun, Q. et al. The effect of prednisolone ingestion and acute exercise on lipocalin-2 and its variants in young men: a pilot randomised crossover study. Sci Rep 15, 4453 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88115-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88115-z