Abstract

Establishing and maintaining colonies of imported fire ants (IFA) (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in the laboratory are crucial for research. Dehydration is one of the major mortality factors in IFA, and the ants tend to relocate from dry to moist places. In our laboratory, we developed a moisture differential technique to extract fire ant colonies from mound materials. In this technique, the shoveled mound soil was dried by spreading in trays at room temperature. Standard glass test tubes half filled with water and plugged with cotton were placed in drying trays to provide a moist habitat. The gradual loss of moisture created a differential between the moist cotton in test tubes and drying soil in trays. Once the soil dried out, IFA moved from trays to moist cotton in the test tubes to avoid dehydration. All stages including the queens were successfully extracted using this technique. In a comparative study, this method recovered 52% more colony mass of hybrid fire ants than the standard water dripping method. Post separation colony survival was also significantly higher in this method as compared to the water dripping method. In addition to separating and maintaining IFA colonies, the moisture differential technique may have additional applications, especially in conducting behavioral bioassays where workers with active digging behavior are needed. Maintenance of laboratory colonies consisting of all life stages in plastic bottles using this new method mimics the field populations that are required to conduct behavioral bioassays.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Red imported fire ant (RIFA; Solenopsis invicta Buren), black imported fire ant (BIFA; S. richteri Forel) (Hymenoptera: Formicidae), and their reproductively functional hybrid (HIFA), hereafter collectively referred as the imported fire ants (IFA), are significant pests of agricultural, urban, and natural habitats1,2,3,4,5,6. IFA is also considered a major public health concern because of the nuisance caused through painful stings7. Imported fire ants invaded the United States from their native South America in the mid-1900s. Now, at least 367 million acres in the United States are reported to be infested by IFA8, resulting in $6.7 billion losses, annually9.

Among these imported fire ants, RIFA is a serious concern as an invasive species that has extended its range beyond the United States because of its strong adaptive and reproductive capacity10,11,12. More than twenty countries and territories around the world are reported to have the presence of RIFA including Australia, China, New Zealand, Japan, South Korea, and the Caribbean islands13,14,15,16,17. Changing climate, massive international trade and interconnected transportation systems are likely to exacerbate the risk of RIFA invasion around the globe18,19. Global projections based on ecological niche models suggest that BIFA can also become an aggressive invader with broader potential in East Asia, South Africa and eastern North America20, however BIFA and HIFA are yet to expand their invasive range beyond United States.

Laboratory colonies of IFA are crucial to study their biology, ecology, toxicology, and behavior as workers, brood, and queens may be required in large numbers. Since IFA are mound building ants, colony fragments are usually collected by shoveling the mound topsoil along the ants in open escape-proof buckets21. Ants must be extracted from the mound soil and maintained under the laboratory using artificial set ups21,22,23,24,25. The common method used by fire ant researchers to separate the ants from soil is the water dripping method, which was originally described by Jouvenaz, et al.26 and later modified by Chen and Wei27. The method is based on the worker ant rafting behavior to avoid drowning when flooded28. In rafting, the workers link their bodies and appendages together to make a ball-shaped floating structure used to move out of water or float as a mat29. These floating rafts of ants are then scooped out. For their subsequent maintenance, escape-proof plastic containers having moist Plaster of Paris made artificial nests are commonly used. There is a frequent need to replace old colonies, when extracted and maintained using these traditional procedures.

The water dripping method is believed to extract enough ants to be used in a short period of time. Other than Chen and Wei27 who reported significant brood losses in using standard water dripping procedure, there are no reports that have described these challenges faced during the process of colony extraction. We are running a natural products screening program, and our behavioral bioassays require workers with active digging behavior. We bring fire ant colonies from the field that are separated from soil/debris and maintained in the laboratory soil. Under traditional procedures, we observed a significant loss of colony during recovery with a high post-recovery mortality and changes occur in worker digging behavior within a few days of recovery. Even the acclimatized ants lose their digging activity and congregate in the arena when released in digging bioassays. To address the challenges faced during colony extraction and rearing, we need monthly replacement of colonies, which is very labor intensive and challenging to handle.

To address the colony losses during extraction, we developed an alternative method, referred to here as moisture differential technique, which can successfully be employed to separate colonies from soil/debris with minimal losses. This method was adopted from Markin25 with some modifications to handle large colonies which was not possible under the original method. This technique implicates the post extraction maintenance of fire ant colonies for an extended period under the laboratory conditions. This paper presents the moisture differential technique by comparing its efficiency with that of water dripping method to extract the fire ant colonies and discusses additional applications of this method in establishing/maintaining laboratory colonies and conducting behavioral bioassays.

Materials and methods

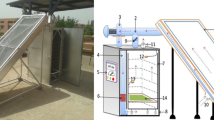

Moisture differential method

The colonies of RIFA, BIFA and HIFA were collected in the morning hours of late fall 2022 and early spring 2023 by digging the mounds and placing the dirt and debris in big buckets lined with talcum powder to prevent their escape. These ant colonies were brought to the laboratory and maintained by feeding crickets and 25% honey-water solution. The ants were kept in collection buckets until they started the normal digging process. After 2–5 days, the mound material was spread in thin layers in plastic trays lined with Insect a Slip and dried under the laboratory conditions at 32 ± 2 °C temperature; 50 ± 10% relative humidity; 12:12 h (L: D) photoperiod. Six to eight standard glass test tubes half filled with water and plugged with cotton were placed in each tray. As the soil dried, the ants moved from drying soil/debris to the test tubes placed in the trays. A comparative study was conducted to estimate the differences in colony mass recovery between water dripping and moisture-differential methods. Given the serious health risks posed by fire ant bites, extra care is needed when working with fire ants in and outside the laboratory environments.

Colony recovery and mortality comparisons

A comparative study was conducted to compare water dripping and moisture differential methods using HIFA colonies. The contents of individual field collected colonies were thoroughly mixed to ensure uniform distribution of fire ants and divided into two equal halves. In order to confirm that the fire ants were uniformly distributed across both halves being compared, five colonies, each split into two equal halves, were extracted using the standard water dripping method. The recovered colony mass showed a non-significant difference for both the halves across five colonies (t = 0.9147; df = 4; P = 0.4121; Fig. 1). These data confirmed that the mixing of colony materials resulted in a uniform spread of ants across both halves of a colony. After establishing the uniformity of distribution, a separate study was conducted to compare colony mass recovery between water dripping and moisture differential methods. The comparative study extracted a total of three field collected colonies, each divided into two equal halves, as described above. Overall, a total of six portions were prepared from three colonies. One half of each of three individual colonies was separated by the dripping method set at a dripping speed of 200–300 drops/minute and the other half by moisture differential method. In the water dripping method, floating rafts were collected and transferred to a rearing container and then the brood buried in debris was floated by manually stirring the submerged soil using a stick. Brood along the dirt/debris that floated over the water surface was collected, screened through a mesh sieve covered with filter paper, and released in the trays with workers. The workers moved the live brood to the colony while the dead ants were placed in refuse piles. The container with left-over mound materials was positioned vertically to drain the water. The left-over workers in the container recovered the buried brood from the submerged soil. The leftover workers were allowed 48–72 h to dig through the submerged soil to rescue the brood. The images and videos of the live and dead brood were recorded. Extracted colonies from both of these methods were subsequently maintained in rearing trays with moisture tubes and 25% sugar-water solution for up to five days to settle.

The number of test tubes filled with ants were counted and piles of dead workers were video recorded for qualitative mortality assessment. The test tubes filled with ants were emptied in a tray lined with black nylon sheet and subsequently transferred into a plastic cup lined with Insect a Slip. Each cup with ants was weighed and colony mass was determined in both methods. Data from these two methods were then compared across three HIFA colonies using the t-test at a 5% level of significance (GraphPad Prism, Version 10).

Maintenance of Ant Laboratory colonies

Mounds provide a suitable microenvironment conducive for colony development. The soil temperature varies within the mound at various depths and the workers move the brood along the vertical planes inside the mounds to optimize thermoregulation30. Movement of the colony at different depths also depends on the soil temperature and moisture levels30,31,32. To ensure normal digging and nesting activities for laboratory bioassays, we modified our rearing system which consisted of a plastic tray, a 2 L plastic beverage bottle with cut top and 4, 1 cm circular holes drilled at the bottom to serve as entry points for ants to move in/out. The bottle was filled with moistened soil and positioned vertically in a tray with 25% sugar-water solution and crickets as food in the tray. The sand in the bottle was moistened weekly by adding 100 mL of water. The moist sand in the bottle provides the workers with a suitable habitat for digging and nesting. This method ensures a regular supply of workers with active digging behavior for use in behavioral bioassays.

Results

In the moisture differential method, gradual evaporation of soil moisture caused the soil to dry out slowly. With the gradual loss of moisture, the workers gathered the brood and accumulated in humid areas of the drying trays to avoid dehydration (Fig. 2 (left); Supp. Video S1). After the complete evaporation of the soil moisture, the ants completely moved to the moist cotton in the test tubes which provided microenvironment conducive for their survival and development. In many cases, early and late stages of the brood were positioned separately within the same tube (Fig. 2 (right); Supp. Video S2). Ants in these tubes were then transferred to rearing containers. The moisture differential method successfully separated RIFA, BIFA and HIFA colonies within 48–72 h.

Set up used to collect imported fire ants from mound soil/debris after gradual drying into standard test tubes (18 × 150 mm) with moist cotton. The presence of alates (left) and the brood (right) is visible. Note the position of young (red round circle) and late brood (red arrows pointing toward larvae and pupae).

Brood losses in modified water dripping

While Chen and Wei27 modification of dripping method recovered significantly more brood than the original water dripping method, a significant mass of brood (larve/pupae) still remained unrecovered (Fig. 3) that was later recovered by the workers from the leftover material in the submerged soil (Supp. Video S3, S4).

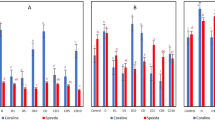

Colony mass recovery

About 52% more colony mass was recovered in the moisture differential method as compared to water dripping method (t = 6.72; df = 2; P = 0.021; Fig. 4b). Number of ant filled test tubes in moisture differential method were approximately double the numbers of ant filled tubes in water dripping method (t = 8.00; df = 2; P = 0.0153; Fig. 4a). Figure 5 presents individual weight of colonies recovered by these two methods. The recoverd mass of three colonies ranged between 24.75 and 32.46 g and 8.55 to 18.14 g in the new method and water dripping method, respectively. Post separation mortality in water dripping method was notably higher than the new method. HIFA colonies extracted through new method were exceptionally clean, and resulted in overall less colony mortality during and post recovery as compared to water dripping method, which showed very high mortality and contained a lot of debris (Fig. 5). Getting rid of unwanted debris may be a challenge in the water dripping method when large colonies have to be handled.

The comparison of ant filled tubes (a) and mean colony weights recovered (b) by water dripping and moisture differential methods. SEM are the standard errors of means. Three colonies of HIFA were collected by shovelling the mounds. Three different colonies were put in three different trays and whole colony contents from each tray were subdivided into two halves after thorough mixing. One half of each colony was separated using water dripping method and the other half by moisture different method. Both methods were thus tested with three different colonies of HIFA (n = 3 per method).

Recovery of HIFA colonies in glass tubes in moisture differential method (left) and water dripping method (right) at 5-d post-release in these trays. Soil/debris of colony dug from the field was thoroughly mixed and separated into two equal halves. Note the number of tubes, combined colony weight (g), dirt/debris, and dead piles indicated by red arrows, in each tray. New glass tubes were added to these trays to collect the colony individuals. Additional tubes were added depending on the colony size.

Maintaining laboratory colonies

To avoid dehydration, IFA needs moist and humid conditions. Vertically positioned moist soil filled bottles were successfully colonized by the fire ants and workers were observed to perform their normal digging/nesting activities in these containers (Fig. 6). Collection of fire ant workers for bioassays was also easy. We simply poked the soil in the plastic bottle from the top with a stick and held it vertically to let the ants crawl on the stick. These sticks are then shaken into the desired containers to collect the workers. With this set up which mimics the natural mound conditions, we were able to effectively maintain fire ant colonies for use in digging bioassays. Immatures and alates are easily extracted from these bottles by manipulating the moisture condition in and outside the bottles. With this advancement, we can keep fire ant colonies active for more than 6 months.

Discussion

Establishing and properly maintaining laboratory colonies of IFA is an essential requirement of research. Different methods, including the water dripping method, are used to extract the ants from the mound materials/debris. Markin25 used the soil drying technique to separate RIFA colonies from the mound soil. They used trap nests made up of Plaster of Paris to create moisture nesting chambers while heated wires were used to prevent the ants from escaping during the drying process. Ants in the moist chambers were anesthetized by exposing them to carbon dioxide and collected using glass tubing. This method was very complicated, logistically difficult to handle and could not handle large colonies because keeping the nest traps moist was a big challenge. In the moisture differential method, water filled glass tubes were used to provide a suitable habitat for ants to gather their brood and colonize while the soil and debris dried out slowly. Once collected in glass tubes, the release of ants to other containers used for maintaining the colonies is very simple and does not need any complicated procedures. Since glass tubes can hold moisture for at least a month, this procedure ensures clean extraction of ant colonies from debris and is more cost-effective and sustainable than the commonly used water dripping method.

The conventional water dripping method caused significant losses of colony individuals and an observed high post-extraction mortality. The causes of this high post extraction colony mortality in water dripping method are not fully known. This high mortality may be because the dead individuals are carried by rafting workers that had to be moved to refuse piles, their elevated alkaloid levels33 or changes in metabolic rates of rafting individuals34. Since separation of brood from workers was not possible, the brood losses were assessed qualitatively only. The losses were much higher in the water dripping method than this new method. As the workers have to carry the brood, in the dripping method which required 2–3 h to separate a colony, the recovery of brood will depend on the worker to brood ratio because one worker will normally carry one individual. The presence of large larvae which are more buoyant and critical during raft formation may be another important factor to consider in the colony mass recovery when flooded35. Based on these findings, while the water dripping method may be able to rapidly extract masses, extraction is required from more colonies due to losses being higher during the extraction process. In contrast to the water dripping, the new method presents a more sustainable and cost-effective alternative as it is very simple, very clean, handy, and recovers more colony mass within 48–72 h under standard laboratory conditions. This variation for extraction time among fire ant species and hybrids could be the result of differences in their responses to abiotic stressors, such as temperature, heat and desiccation36,37. Variation among soil types and its moisture content may be another important contributing factor for this variation as different ants were collected from different places. Based on this, scaling up the method for large numbers of colonies and according to different fire ants requires the use of many drying trays and removing and spreading the soil in thin layers under the standard laboratory conditions. Speed of recovery under this new method can be improved by manipulating the drying process according to requirements of fire ant species and hybrids. This method may be used only under standard controlled conditions as extreme temperatures or humidity may have adverse impacts, such as insects may desiccate or die or may deviate from their normal behavior.

Traditional colony extraction and maintenance set ups lead to high subsequent mortality, thereby increasing labor and maintenance costs. Since ants are soil dwelling creatures, maintaining ant colonies in soil filled containers will provide ants with a natural type of micro-environment conductive for their development that will ensure continuation of normal digging behavior. This study did not compare digging activity over an extended period between these two methods. Further studies will be conducted to determine the length of time the ants will maintain their digging activity under water dripping versus this alternative method. Future studies should also compare long-term impacts of these methods on worker foraging behavior and other key indicators including aggressiveness, walking speed, grasping ability, that are critical to the survival of ant colonies38,39. With this additional information, the suitability of this method toward the goal of sustainable laboratory colonies management can be determined.

While the moisture differential method was conceived and developed during our process of establishing the laboratory colonies for our natural product screening program, the method may have additional uses. By manipulating moisture contents, the ants can be made to move from one to the other location. This moisture-guided behavior may be used to test digging or nesting activities on the treated surfaces. For example, the effectiveness of natural products as quarantine treatments may be determined by residual bioassays. Chemicals through long-term suppressive effects on worker nesting or digging abilities may eliminate fire ant infestations from treated areas. We have successfully used this method to manipulate ant movement in our residual bioassays, where in the presence of equal levels of moisture in treated versus untreated control, the ants enter the control. As the moisture dries, we only apply moisture to the treated surface while dried sand in control becomes unsuitable for survival. This leaves workers with a choice to avoid dehydration by entering the treatment but if repellency/toxicity is too high to prevent the entrance the ants dehydrate and die in trays. As such the spread of IFA through transportation of nursery stocks from one place to another may be reduced in quarantine systems. The small laboratory colonies of IFA, including brood, alates and queens, can be established in plastic bottles and individuals may be removed as per need by employing the moisture differential method. This method will be highly useful in conducting different studies related to understanding life history parameters, behavior and physiology of imported fire ants. We will be continuously working to find the additional applications of this method in fire ant research.

Conclusion

The moisture differential method recovered more mass of fire ant colonies than water dripping method. A notable reduction in the subsequent colony mortality was observed in the moisture differential method as compared to the water dripping method. Based on these differences, this new method appears to be more efficient and convenient for the extraction and subsequent maintenance of fire ant colonies under laboratory conditions. As by manipulating the ants to move or relocate, this method may be used to maintain small ant colonies and conduct various types of behavioral bioassays by regulating ant movement. Further research will be continued to explore additional uses of this method.

Data availability

All data from this study are included within this manuscript.

References

Morrison, J. E. Jr, Williams, D. F., Oi, D. H. & Potter, K. N. Damage to dry crop seed by red imported fire ant (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). J. Econ. Entomol. 90, 218–222 (1997).

Lard, C., Willis, D. B., Salin, V. & Robison, S. Economic assessments of red imported fire ant on Texas’ urban and agricultural sectors. Southwest. Entomol. 25, 123–137 (2002).

Wu, D., Zeng, L., Lu, Y. & Xu, Y. Effects of Solenopsis invicta (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) and its interaction with aphids on the seed productions of mungbean and rapeseed plants. J. Econ. Entomol. 107, 1758–1764 (2014).

Vinson, S. B. Impact of the invasion of the imported fire ant. Insect Sci. 20, 439–455 (2013).

Gibbons, L. & Simberloff, D. Interaction of hybrid imported fire ants (Solenopsis invicta× S. richteri) with native ants at baits in southeastern Tennessee. Southeast. Nat. 4, 303–320 (2005).

Siddiqui, J. A. et al. Impact of invasive ant species on native fauna across similar habitats under global environmental changes. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. 28, 54362–54382 (2021).

Lopez, D. J. et al. The human health impacts of the red imported fire ant in the Western Pacific Region context: a narrative review. Trop. Med. Infect. Disease. 9, 69 (2024).

Kemp, S. F., DeShazo, R. D., Moffitt, J. E. & Williams, D. F. Buhner II, W. A. Expanding habitat of the imported fire ant (Solenopsis invicta): a public health concern. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 105, 683–691 (2000).

Tschinkel, W.R. The Fire Ants; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2006; pp. 723 (2006).

Wang, H. et al. Impacts of changing climate on the distribution of Solenopsis invicta Buren in Mainland China: exposed urban population distribution and suitable habitat change. Ecol. Ind. 139, 108944 (2022).

Morrison, L. W., Porter, S. D., Daniels, E. & Korzukhin, M. D. Potential global range expansion of the invasive fire ant, Solenopsis invicta. Biol. Invasions. 6, 183–191 (2004).

Chen, J., Rashid, T. & Feng, G. A comparative study between Solenopsis invicta and Solenopsis richteri on tolerance to heat and desiccation stresses. PLoS ONE. 9, e96842 (2014).

Davis, L. R. Jr, Van der Meer, R. K. & Porter, S. D. Red imported fire ants expand their range across the West Indies. Fla. Entomol., 735–735 (2001).

Sung, S., Kwon, Y. S., Lee, D. K. & Cho, Y. Predicting the potential distribution of an invasive species, Solenopsis invicta Buren (Hymenoptera: Formicidae), under climate change using species distribution models. Entomol. Res. 48, 505–513 (2018).

Sutherst, R. W. & Maywald, G. A climate model of the red imported fire ant, Solenopsis invicta Buren (Hymenoptera: Formicidae): implications for invasion of new regions, particularly Oceania. Environ. Entomol. 34, 317–335 (2005).

Zeng Ling, Z. L., Lu YongYue, L. Y., He XiaoFang, H. X. & Zhang WeiQiu, Z. W. Liang GuangWen, L. G. Identification of red imported fire ant, Solenopsis invicta, to invade mainland China and infestation in Wuchuan, Guangdong. Chin. Bull. Entomol. 42, 144–148 (2005).

Zhang, R., Li, Y., Liu, N. & Porter, S. D. An overview of the red imported fire ant (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in mainland China. Fla. Entomol. 90, 723–731 (2007).

Li, D. et al. Climate change and international trade can exacerbate the invasion risk of the red imported fire ant Solenopsis invicta around the globe. Entomol. Generalis. 43, 315–323 (2023).

Ascunce, M. S. et al. Global invasion history of the fire ant Solenopsis invicta. Science 331, 1066–1068 (2011).

Peterson, A. & Nakazawa, Y. Environmental data sets matter in ecological niche modelling: an example with Solenopsis invicta and Solenopsis richteri. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 17, 135–144 (2008).

Banks, W. A. et al. (USDA SEA AATS-S-21, (1981).

Khan, A., Green, H. & Brazzel, J. Laboratory rearing of the imported fire ant. J. Econ. Entomol. 60, 915–917 (1967).

Bishop, P. et al. Simple nests for culturing imported fire ants [Solenopsis invicta, Solenopsis richteri, biological control]. J. Ga. Entomol. Soc. (1980).

Williams, D., Lofgren, C. & Lemire, A. A simple diet for rearing laboratory colonies of the red imported fire ant. J. Econ. Entomol. 73, 176–177 (1980).

Markin, G. P. Handling techniques for large quantities of ants. J. Econ. Entomol. 61, 1744–1745 (1968).

Jouvenaz, D., Allen, G., Banks, W. & Wojcik, D. P. A survey for pathogens of fire ants, Solenopsis spp., in the southeastern United States. Fla. Entomol., 275–279 (1977).

Chen, J. & Wei, X. An improved method for fast and efficient fire ant colony separation. Proceedings of Annual Red Imported Fire Ant Conference. Gulfport, Mississippi, 173-175 (2005).

Mlot, N. J., Tovey, C. A. & Hu, D. L. Fire ants self-assemble into waterproof rafts to survive floods. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 108, 7669–7673 (2011).

Goddard, J. & de Shazo, R. D. Envenomation from flood-related fire ant rafting: a cautionary note. Am. J. Med. 136, 937–940 (2023).

Penick, C. A. & Tschinkel, W. Thermoregulatory brood transport in the fire ant, Solenopsis invicta. Insectes Soc. 55, 176–182 (2008).

Pranschke, A. & Hooper-Bui, L. Influence of abiotic factors on red imported fire ant (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) mound population ratings in Louisiana. Environ. Entomol. 32, 204–207 (2003).

Xu, Y., Zeng, L., Lu, Y. & Liang, G. Effect of soil humidity on the survival of Solenopsis invicta Buren workers. Insectes soc. 56, 367–373 (2009).

Haight, K. L. Defensiveness of the fire ant, Solenopsis invicta, is increased during colony rafting. Insectes Soc. 53, 32–36 (2006).

Ko, H., Komilian, K., Waters, J. S. & Hu, D. L. Metabolic scaling of fire ants (Solenopsis invicta) engaged in collective behaviors. Biol. Open. 11, bio059076 (2022).

Adams, B. J., Hooper-Bùi, L. M. & Strecker, R. M. O´ Brien, D. M. raft formation by the red imported fire ant, Solenopsis invicta. J. Insect Sci. 11, 171 (2011).

Chen, J., Rashid, T. & Feng, G. A comparative study between Solenopsis invicta and Solenopsis richteri on tolerance to heat and desiccation stresses. PLoS One. 9, e96842 (2014).

James, S. S., Pereira, R. M., Vail, K. M. & Ownley, B. H. Survival of imported fire ant (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) species subjected to freezing and near-freezing temperatures. Environ. Entomol. 31, 127–133 (2002).

Lai, L. C., Hua, K. H. & Wu, W. J. Intraspecific and interspecific aggressive interactions between two species of fire ants, Solenopsis geminata and S. Invicta (Hymenoptera: Formicidae), in Taiwan. J. Asia. Pac. Entomol. 18, 93–98 (2015).

Roeder, K. A., Prather, R. M., Paraskevopoulos, A. W. & Roeder, D. V. The economics of optimal foraging by the red imported fire ant. Environ. Entomol. 49, 304–311 (2020).

Acknowledgements

We are thankful to Dr. Jian Chen, USDA-ARS, Stoneville, Mississippi for identifying the fire ants.

Funding

This research was funded in part by USDA-ARS, grant No. 58-6066-1-025.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, FMS and AA; methodology, FMS and A.A; software FMS and AA; validation, FMS and AA; formal analysis, FMS and AA; investigation, FMS and AA; resources, IAK; data curation, AA; writing—original draft preparation FMS, and AA; writing—review and editing, FMS, AA, and IAK; visualization, AA; supervision, AA; project administration, AA.; funding acquisition, IAK. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shah, F.M., Khan, I.A. & Ali, A. A moisture differential technique for extraction and maintenance of imported fire ant colonies under laboratory conditions. Sci Rep 15, 3742 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88116-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88116-y