Abstract

We investigate the synergistic effects of chromocene intercalation (GeS–Cr\((\mathrm {C_5H_5})_2\)) and randomly distributed sulfur vacancies on the optoelectronic properties of atomically thin GeS using advanced first-principles many-body simulations. We demonstrate the emergence of a magnetic ground state in GeS, driven by weak chemical interactions between the GeS host and the intercalated organometallic chromocene. Using large-scale, first-principles many-body simulations that account for randomly distributed sulfur vacancies and the dielectric screening within the hybrid material, we show the tunability of the optoelectronic features. Specifically, we observe enhanced absorption in the range of \(\sim\) 0.21 to 3.5 eV, including absorption below the bandgap threshold as the vacancy concentration is tuned between 1 and 5%. The emergent Lifshitz tails are in excellent agreement with our numerical calculations. The predicted features and tunability underscore the potential of defect engineering for applications in magneto-optics and high-density data storage, where precise manipulation of light with magnetic fields is crucial for advanced applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Recent advances in two-dimensional (2D) materials have opened new avenues for technological innovation across a range of applications, from electronics and optoelectronics to energy storage and quantum information processing1,2,3. Among these materials, group IV monochalcogenides such as germanium sulfide (GeS)4 are particularly notable for their exceptional optoelectronic properties, which include a strong light-matter interaction that manifests itself in substantial absorption in the visible light and near-infrared spectra, along with high carrier mobility. These characteristics are crucial for the development of efficient, next-generation electronic devices5,6,7,8. Moreover, these properties can be further tailored through doping, defect engineering, or intercalation—the insertion of atoms, ions, or molecules into the van der Waals gaps of layered materials9,10. Intercalation has emerged as a particularly innovative technique for designing exotic materials and is predominantly a well-studied approach for 2D structures that feature natural van der Waals gaps between vertically stacked layers. It has proven to be an effective and controlled method for enhancing the properties of materials through engineered structural modifications6,7,8,9,10,11. For instance, the optoelectronic properties of Group IV-based hybrid materials have shown significant improvement following intercalation, including substantial enhancements in ultrafast near band-edge photoconductivity and the emergence of intermediate band states12. The intercalation of organically active molecules has recently emerged as a powerful technique to further enhance the optoelectronic features of a variety of 2D materials13,14,15,16. Organometallics are particularly interesting due to their ability to introduce novel electronic states and functionalities within the host material, thus expanding their utility in advanced optoelectronic applications11,17. However, to support the development of any practical applications, we also need to develop a better understanding of the role and impact of randomly distributed native impurities, such as chalcogen vacancy in quantum material. Although the effect of chalcogen vacancies is well-studied in GeS single layers and bulk materials where deep trap states are realized18,19,20, its interplay with intercalation has not been explored to guide experimentation and device fabrication.

In this letter, we design a hybrid quantum material, chromocene-intercalated GeS (GeS–Cr\((\mathrm {C_5H_5})_2\)), achieved by intercalating chromocene (Cr\((\mathrm {C_5H_5})_2\)) into the van der Waals gap of vertically stacked atomically thin layers of 2D GeS. Chromocene is among the metallocene family of organometallics consisting of a chromium atom sandwiched between two cyclopentadienyl (Cp\(_2\)) rings, which introduce unique electronic modifications to the host lattice post-intercalation16. Our advanced many-body simulations reveal several novel features atypical of pristine GeS, which indicate promising material for next-generation device applications. Firstly, the intercalation of Cr\((\mathrm {C_5H_5})_2\) induces a magnetic ground state accompanied by the emergence of a characteristic flat band in proximity to the Fermi level. The presence of this flat band with magnetic behavior is crucial as it suggests strong electron correlations that stabilize the magnetic order, potentially leading to new quantum phases and enhancing electron–electron interactions. Such properties are particularly valuable for applications in quantum computing and magnetic sensors, where control over quantum states and their coherence is essential. Secondly, we demonstrate that randomly distributed sulfur vacancies significantly impact the optoelectronic properties of the material. Specifically, these vacancies enhance the magnetic behavior and increase band-to-band absorption, including the emergence of low excitonic excitation states below the bandgap. This could be particularly advantageous for solar cell applications that benefit from a large absorption in the range \(\sim 0.21-3.5\) eV. The enhanced absorption coupled with low-energy excitonic states allows for efficient light harvesting and charge separation, which are critical for high-efficiency solar cells. Moreover, the novel properties induced by sulfur vacancies extend the utility of GeS–Cr\((\mathrm {C_5H_5})_2\); the ability to manipulate spin states without the need for external magnetic fields can lead to more energy-efficient devices. Similarly, the enhanced magnetic properties and stability provided by these vacancies could improve the performance and durability of magnetic data storage devices.

Computational method

A significant challenge in our investigation is that modeling low disorder concentrations is computationally intractable using the many-body approaches such as GW method, and random defects cannot be incorporated within a DFT-based formalism. To accurately describe many-body effects and exciton structures in the presence of random defects, we adopt an approach based on the dynamical mean-field theory. The first-principles-based typical medium dynamical cluster approximation (TMDCA) maps a disordered lattice onto an effective medium through a set of self-consistency equations21,22,23. We have solved the Bethe-Salpeter Equation (BSE) to obtain the absorption spectra from our self-consistent TMDCA calculations, which account for both sulfur vacancies and electron–electron interactions. To capture the physics of random defects and electron–electron interactions, we utilize the Anderson-Hubbard model:

where \(\hat{H}_0\) is the Hamiltonian of the pristine crystal, \(V_{i\sigma }^\alpha\) denotes the disorder potential, \(\hat{n}_{i\sigma }^\alpha\) is the number operator, and \(U = 6.0\) eV is the Hubbard parameter. The primes on the sums indicate that the disorder affects only the sulfur orbitals, while the electron–electron interactions are confined to the Cr-d states.

Results and discussion

To simulate intercalated GeS–Cr\((\mathrm {C_5H_5})_2\), we performed structural relaxation and electronic structure calculations using the VASP electronic structure suite24, describing electron and ion interactions using the projector augmented wave method25. Our model consists of a \(2 \times 2 \times 1\) bilayer GeS, optimized using the Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof exchange-correlation functional26. All calculations were carried out with a 500 eV kinetic energy cutoff, using a \(3 \times 3 \times 1\) \(\Gamma\)-centered k-point grid for Brillouin zone sampling, and included van der Waals interactions via the DFT-D3 parameterization27.

Subsequently, self-consistent quasiparticle Green’s function and screened Coulomb interaction (sqGW) calculations were performed, incorporating local field effects beyond the random phase approximation using an energy cutoff of 160 eV. The obtained quasiparticle wavefunction from our sqGW was used to optimize the \(U\) value (\(\sim 6.0\) eV), which was then employed to perform DFT+\(U\) calculations applied in WANNIER9028 to obtain \(\hat{H}_0\) via a downfolding method. For the GeS–Cr\((\mathrm {C_5H_5})_2\) hybrid system, our focus is on the Ge-\(s\) and \(p\) orbitals, S-\(s\) and \(p\) orbitals, and Cr-\(d\) orbitals, which dominate the states around the Fermi level. These states were downfolded and used to construct \(\hat{H}_0\) to capture the low-energy Hilbert space within the range of \([-5.2, 5.2]\) eV around the Fermi level. The obtained effective Hamiltonian, \(\hat{H}_0\), shows excellent agreement with the first-principles calculations from which it was derived. The 133 bands generated by the 64 \(s\) and \(p\) orbitals on the Ge atom, the 64 \(s\) and \(p\) orbitals on the S atom, and the 5 \(d\) orbitals on the Cr atom accurately reflect the structure of the DFT + \(U\) bands around the Fermi level (Figure S1a & S2a). Although the TMDCA formalism self-consistently incorporates spatial correlations, due to the large number of orbitals and the difficulty in converging the exciton features, we present results obtained using a single-site cluster and a hexagonal grid of \(10 \times 10 \times 1\) k-points.

The randomly distributed sulfur vacancies are modeled through the disorder potential \(V_{i\sigma }^\alpha\) in Eq. (1). Assuming no explicit orbital and spin dependence, this disorder potential simplifies to a site potential \(V_i\). We generate this site potential from a two-point distribution with \(V_i \in \{0, V_\text {vac}\}\), where the potentials correspond to nonvacant and vacant sites, respectively. To prevent electron occupation at vacant sites, we set \(V_\text {vac}\) to be much higher than the material bandwidth, with the probability of vacancy given by the sulfur vacancy concentration parameter \(\delta\)22.

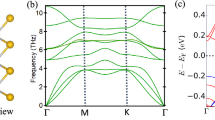

Electronic structure of GeS-based quantum material: (a) Band structure of Cr\((\mathrm {C_5H_5})_2\) intercalated GeS bilayer with spin-up and spin-down channels represented by red and blue curves, respectively, and (b) total density of states with and without 2% sulfur vacancy concentration for GeS–Cr\((\mathrm {C_5H_5})_2\). The Fermi level is shifted to 0 eV. Note that the TMDCA spectra are the normally, averaged ones obtained within the typical medium.

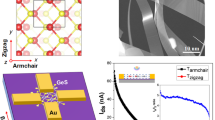

Structural and stability analysis The intercalated quantum material was computationally synthesized by positioning a metallocene end-to-end parallel to the c-axis within a \(2\times 2\times 1\) AA-stacked GeS system size, characterized by the orthorhombic crystal structure symmetry of Pnma and space group number 62 (Fig. 1). Upon relaxation, the structure transitioned to a \(Pmn2_1\) symmetry with space group number 31. This orientation of the intercalant has been previously identified as the energetically favorable configuration10,11. Post-intercalation, the optimized bilayer structure exhibited lattice constants a = 3.70 Å and b = 4.31 Å. The Ge-S bond lengths are \(d_1\sim \,\)2.42 Å and \(d_2\sim \,\)2.49 Å in the zigzag and armchair directions, respectively, which showed negligible changes from the pristine material, indicating minimal distortion of the host lattice upon intercalation16. Additionally, the van der Waals gap increased to 9.67 Å, aligning well with the physical dimensions of the chromocene molecule (3.69 Å) inserted into the vdW gap of the bilayer. This correlates with the expanded monolayer separation and is consistent with prior findings10,11,29,30.

Mechanical and energetic stability are pivotal in evaluating the feasibility of materials for experimental synthesis and device integration. We utilized the ELASTool code31,32,33 to examine the mechanical stability of our synthesized material. The analysis revealed robust mechanical properties, with 2D Young’s modulus and stiffness parameters comparable to those of the host material in Table S1 in the Supplementary Material. To assess energetic stability, total energy calculations were conducted to determine the intercalation energy, \(E_i = (E_{\text {Hyb}} - E_{\text {2D}} - E_{\text {M}})\), where \(E_{\text {Hyb}}\), \(E_{\text {2D}}\), and \(E_{\text {M}}\) represent the total energies of the ground state of the intercalated hybrid material, pristine bilayer GeS and chromocene, respectively, \(E_i\) provides a measure of the energy required to insert a guest specie into a host material. Our findings reveal \(E_i \sim 0.54\) eV, indicating a very low energy cost for the insertion of the chromocene into the van der Waals gap of the AA-stacked bilayer. This low value suggests that the intercalation process is potentially spontaneous, further underscoring the potential for experimental synthesis.

Electronic and magnetic properties. The intercalation of Cr\((\mathrm {C_5H_5})_2\) into GeS significantly alters the electronic and magnetic properties of the host material. As shown in Fig. 2, the electronic structure of GeS, intercalated with approximately \(3\%\) concentration of Cr\((\mathrm {C_5H_5})_2\), is characterized by notable changes in both the band structure (Fig. 2a) and the density of states (Fig. 2b). Pristine GeS typically exhibits a nonmagnetic ground state with a quasiparticle bandgap for the bilayer host of approximately 2.20 eV (see Figure S3); however, Cr\((\mathrm {C_5H_5})_2\)-intercalated GeS displays a magnetic moment of approximately \(1.86\,\mu _B\), mainly from the Cr-d states (see Table S2), and is accompanied by an enhanced quasiparticle bandgap of \(\sim 3.23\) eV and a characteristic flat band near the Fermi level16.

The magnetic ground state of the hybrid structure arises from nonlocal dynamics in the crystal. Within the local environment of Cr\((\mathrm {C_5H_5})_2\), Cr is known to violate the 18-electron rule due to uncompensated Cr-d electrons. Primarily, the interactions between the uncompensated electrons on Cr d orbitals and the valence band states of GeS, predominantly composed of S-s and p and Ge-p states, play a crucial role. Crystal field analysis, supported by the atomic and orbital-resolved density of states (Figure S1b & S2b), reveals significant hybridization resulting from the proximity of chromocene to the GeS layers (Fig. 1b). The d orbitals of Cr, having acquired electron density from the Cp\(_2\) rings through the donation of \(d-\pi\) electrons, subsequently donate electron density to the adjacent S atoms in the GeS layers. This interaction leads to the partial filling of states near the Fermi level, thereby altering the local electronic structure, a signature of spontaneous symmetry breakage in the system. Similarly, back-donation occurs from the Cr-d orbitals to the empty or partially filled states of GeS. The polarization of the spins is a signature of this symmetry breakage, resulting from the combined effects of electronic and exchange interactions. These interactions cause the magnetic moments of the hybrid to align in a particular direction, leading to a magnetic solution. The rearrangement of electron density in the local environment of the central Cr atom, due to electronic interactions between the intercalant and the GeS lattice, is the source of the hybrid’s magnetic properties. Furthermore, the unpaired electrons in the Cr 3d orbitals experience exchange interactions with the electrons in the GeS lattice, leading to preferential spin alignment and the introduction of new localized spin-polarized electronic states, which are evident from the flat band observed in the electronic band structure (Fig. 2a). The inherent magnetism introduced by intercalation, along with the resultant modification of the density of states, holds considerable promise for high-performance applications in electrophotonics. The ability to induce and control magnetic properties in otherwise nonmagnetic 2D materials such as GeS through chromocene intercalation paves a new pathway for the design and development of advanced functional materials.

Recent experiments have demonstrated that intrinsic native defects, such as vacancies, are prevalent in chalcogen-based materials such as MoS\(_2\)34,35,36,37,38. These findings have led us to model the effects of a low sulfur vacancy concentration (1–\(5\%\)) in our hybrid quantum material. Traditional many-body simulations, such as GW, often find such low concentrations intractable. However, the application of a first-principles-based TMDCA has enabled the simulation of these effects, incorporating 133 orbitals, thus facilitating large-scale computational modeling. Our TMDCA simulations reveal a substantial spectral weight transfer to the localized flat bands in the spin-down channel, indicative of strong electronic interactions modified by the presence of vacancies. Typically, Anderson-localized states, which emerge in disordered systems, might become delocalized in the presence of strong Coulomb interactions due to the interplay between Mott physics (which promotes electron localization due to electron–electron interaction) and Anderson localization (which results from disorder). In our study, rather than leading to delocalization, we observe an enhancement of the localized states, characterized by a significant increase in the density of states within the spin-down channel (Fig. 2b). This enhancement suggests a dominating influence of the disorder-induced localization over the Coulomb interaction-induced delocalization in our material system. Additionally, we observed a reduction in the quasiparticle bandgap, possibly due to increased localization and the modification of the local environment by sulfur vacancies. Furthermore, varying the concentration of sulfur vacancies resulted in minor changes in the spin polarization. This included spectral weight transfers to the Fermi energy, as shown in Figure S5. These findings underscore the complex interplay between disorder and electronic interactions in 2D quantum materials and highlight the potential of engineered vacancies to tailor the electronic properties of intercalated materials for advanced optoelectronic applications.

Optical properties. To investigate the absorption features of GeS–Cr\((\mathrm {C_5H_5})_2\), we employed many-body approaches, sqGW-BSE and TMDCA-BSE for the system without and with random S vacancy, respectively. Within the TMDCA, the screening caused by electron polarization resulting from excitations within the material is described by the susceptibility, \(\chi (\omega )\)22, which is related to the complex dielectric function, \(\varepsilon (\omega )\), through the equation \(\chi (\omega ) = \epsilon (\omega ) - \mathbbm {I}\), where \(\mathbbm {I}\) is the identity matrix. Both sqGW-BSE and TMDCA-BSE take into account electron-hole interactions, which are essential to properly characterize transport dynamics in 2D-based systems. The absorption spectra are characterized by the dynamical complex dielectric function, \(\varepsilon (\omega )=\varepsilon _1{(\omega )}+i\varepsilon _2{(\omega )}\) with \(\varepsilon _1\) (dispersive) and \(\varepsilon _2\) (absorptive) as the real and imaginary parts, respectively. We note that within the TMDCA, the dynamical complex dielectric function is calculated using the averaged lattice and cluster Green’s functions derived from the typical medium. This approach is essential, as only these averaged Green’s functions preserve sum rules and accurately represent the material’s physical properties. Unlike the typical density of states, which does not conserve sum rules, the averaged lattice Green’s functions reflect the true underlying dynamics, allowing for precise computation of quantities such as the complex dielectric function21,22.

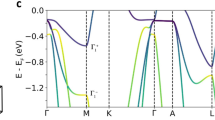

Absorption spectra of GeS-based quantum materials: (a) Imaginary part of the complex dielectric function for pristine GeS and GeS–Cr\((\mathrm {C_5H_5})_2\) (calculated with sqGW-BSE) and GeS–Cr\((\mathrm {C_5H_5})_2\) with 2% sulfur vacancy concentration (calculated with TMDCA-BSE) and (b) defect-engineering at various sulfur vacancy concentrations, \(\delta\), obtained with Eq. 2. Increasing the concentration \(\delta\) of sulfur vacancies leads to enhancement of the generation of free electron-hole pairs and hence increases the optical absorption below the optical bandgap \(E_g=2.42\) eV.

We present in Fig. 3a, the imaginary part of the dielectric function for pristine bilayer GeS, intercalated GeS, and intercalated GeS with a 2% concentration of random sulfur vacancies. Furthermore, using the electronic band gap of the quasiparticle derived from our DFT+sqGW calculations, we estimate the exciton binding energy \(E_b\) to be 0.46 eV for the pristine bilayer and 0.81 eV for the intercalated structure, which is in agreement with our previous study. These results underscore the significant impact of intercalation on the optical and electronic properties of GeS. The computed \(E_b\) values are the upper limit of experimental values, which are in the range of 0.2–0.8 for transition metal chalcogenides, presumably because our calculations do not take into account screening from substrates. Intriguingly, pristine GeS, a non-magnetic semiconductor, exhibits superior low-energy optical excitations, which diminish post-intercalation. Nevertheless, the introduction of a magnetic moment by Cr in the intercalated GeS enhances its properties, making it particularly relevant for various advanced technological applications. This significance is emphasized by the enhancement of the absorption \(\varepsilon _2\), which results from the complex interplay between the degrees of freedom of the vacancy and the magnetic properties induced by the intercalant. The introduction of sulfur vacancies into GeS–Cr(Cp)\(_2\) leads to a significant enhancement of the absorption spectra in both the near-infrared and visible regimes. Specifically, the absorption coefficient of the intercalated structure increases tenfold at the onset of absorption with a 2% sulfur vacancy concentration (Figure S6). In addition to the major contribution to the excitation energy above the bandgap edge associated with the generation of free electron-hole pairs, the imaginary part of the dielectric function is characterized by quasiparticle excitations around 0.21 eV, followed by low-energy (infrared) optical excitations.

Furthermore, the overall impact of sulfur vacancies on \(\varepsilon _2(\omega )\) varies across the spectrum. Above the bandgap transition energy, an increase in vacancy concentration generally results in a decrease in \(\varepsilon _2(\omega )\), as depicted in Figure S7. This decrease correlates with the disruption of extended states within the conduction and valence bands by the vacancies, reducing the generation of free-electron-hole pairs. In contrast, below the band gap threshold, \(\varepsilon _2(\omega )\) typically increases with an increase in vacancy concentration, indicative of an increase in the number of carriers near the band edges—a phenomenon familiar in disordered systems known as Lifshitz tails22,39. These states arise due to local perturbations of the electron–electron interactions near the vacant sites. With a substantial vacancy concentration, we anticipate that the absorption features in this subthreshold regime will be predominantly governed by excitations between these complex states, i.e., the interplay between Coulomb interactions and vacant sites. The relationship is modeled by:

The predicted trend is similar to those reported for monolayer MoS\(_2\)22. We used \(\varepsilon _2(E_g) \approx 4.92\), a value that matches remarkably with \(\varepsilon _1(\omega \rightarrow 0)\) for pristine bilayer GeS (Figure S6), and \(\gamma (\delta ) \approx -\frac{1}{12}(3 + 3\log _2 \delta )\,\textrm{eV}^{-1}\) in Fig. 3b, obtaining excellent qualitative agreement with our first-principles-based calculations (see Figure S8).

Conclusion

In summary, we have investigated the effects of metallocene intercalation using chromocene (GeS–Cr\((\mathrm {C_5H_5})_2\)) and the integration of random sulfur vacancies on the structural, magnetic, and electronic properties of 2D GeS materials. Advanced computational techniques, including many-body typical medium calculations, reveal the emergence of a spin-polarized magnetic ground state with a magnetic moment of 1.86 \(\mu _B\), which is atypical for pristine GeS, post-intercalation. The incorporation of random sulfur vacancies further amplifies these features, introducing new states in the absorption spectrum such as enhancements in optical activity ranging from 0.21 to 3.5 eV, indicative of Lifshitz tails, which lead to increased optical absorption below the bandgap. These results reveal a complex interplay between intercalation-induced magnetic order, electronic interactions, and native defects, illustrating the tunability of the unique properties of 2D GeS to enable novel features in quantum materials. These advancements are promising for applications in technologies such as dilute magnetic semiconductors, optoelectronics, solar cells, magnetic storage, and quantum information processing.

Data availibility

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Xia, F., Wang, H., Xiao, D., Dubey, M. & Ramasubramaniam, A. Two-dimensional material nanophotonics. Nat. Photonics 8, 899 (2014).

Bhimanapati, G. R. et al. Recent advances in two-dimensional materials beyond graphene. ACS Nano 9, 11509 (2015).

Xu, M., Liang, T., Shi, M. & Chen, H. Graphene-like two-dimensional materials. Chem. Rev. 113, 3766 (2013).

Malone, B. D. & Kaxiras, E. Quasiparticle band structures and interface physics of SnS and GeS. Phys. Rev. B 87, 245312. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.87.245312 (2013).

Zhou, J. et al. Layered intercalation materials. Adv. Mater. 33, 2004557 (2021).

Rajapakse, M. et al. Intercalation as a versatile tool for fabrication, property tuning, and phase transitions in 2d materials. npj 2D Mater. Appl. 5, 30. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41699-021-00211-6 (2021).

Zhu, Y., Gao, T., Fan, X., Han, F. & Wang, C. Electrochemical techniques for intercalation electrode materials in rechargeable batteries. Acc. Chem. Res. 50, 1022. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.accounts.7b00031 (2017).

Hao, J. et al. First-principles investigation of aluminum intercalation in bilayer blue phosphorene for al-ion battery. Surf. Sci. 728, 122195 (2023).

Kwak, I. H. et al. Intercalation of cobaltocene into WS 2 nanosheets for enhanced catalytic hydrogen evolution reaction. J. Mater. Chem. A 7, 8101 (2019).

Kuo, D.-Y., Rice, P. S., Raugei, S. & Cossairt, B. M. Charge transfer in metallocene intercalated transition metal dichalcogenides. J. Phys. Chem. C 126, 13994 (2022).

Najmaei, S., Ekuma, C. E., Wilson, A. A., Leff, A. C. & Dubey, M. Dynamically reconfigurable electronic and phononic properties in intercalated hfs2. Mater. Today 39, 110 (2020).

Kastuar, S. M. & Ekuma, C. E. Chemically tuned intermediate band states in atomically thin Cu x GeSe/SnS quantum material for photovoltaic applications. Sci. Adv. 10, eadl6752 (2024).

Bao, W. et al. Approaching the limits of transparency and conductivity in graphitic materials through lithium intercalation. Nat. Commun. 5, 4224 (2014).

Xiong, F. et al. Li intercalation in MoS2: In situ observation of its dynamics and tuning optical and electrical properties. Nano Lett. 15, 6777 (2015).

Zhang, L. & Zunger, A. Evolution of electronic structure as a function of layer thickness in group-VIB transition metal dichalcogenides: Emergence of localization prototypes. Nano Lett. 15, 949 (2015).

Iloanya, A., Kastuar, S., Ekuma, C. Tailoring electrophotonic capabilities of atomically thin GeS through controlled organometallic intercalation. J. Appl. Phys. 136 (2024)

Lê, T. N. N., et al. Electronic properties of electroactive ferrocenyl-functionalized MoS2. Preprint at arXiv:2404.10565 (2024).

Mishra, N. & Makov, G. Ab initio study of intrinsic point defects in germanium sulfide. J. Alloy. Compd. 914, 165389 (2022).

Choi, H.-K., Cha, J., Choi, C.-G., Kim, J. & Hong, S. Effect of point defects on electronic structure of monolayer GeS. Nanomaterials 11, 2960 (2021).

Qiu, C. et al. First-principles study of intrinsic point defects of monolayer GeS. Chin. Phys. Lett. 38, 026103 (2021).

Ekuma, C. E., Dobrosavljević, V. & Gunlycke, D. Firstprinciples-based method for electron localization: Application to monolayer hexagonal boron nitride. Phys. Rev. Lett. 118, 106404. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.118.106404 (2017).

Ekuma, C. E. & Gunlycke, D. Optical absorption in disordered monolayer molybdenum disulfide. Phys. Rev. B 97, 201414. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.97.201414 (2018).

Ekuma, C. E. et al. Typical medium dynamical cluster approximation for the study of Anderson localization in three dimensions. Phys. Rev. B 89, 081107. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.89.081107 (2014).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Joubert, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 59, 1758 (1999).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865 (1996).

Grimme, S., Antony, J., Ehrlich, S., Krieg, H. A consistent and accurate ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys. 132 (2010).

Mostofi, A. A. et al. wannier90: A tool for obtaining maximallylocalised Wannier functions. Comput. Phys. Commun. 178, 685. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpc.2007.11.016 (2008).

Gong, Y. et al. Ferrocene preintercalated vanadium oxides with rich oxygen vacancies for ultrahigh rate and durable zn-ion storage. Electrochim. Acta 439, 141693 (2023).

Rodríguez-Castellón, E., Jiménez-Ĺópez, A., Martínez-Lara, M. & Moreno-Real, L. Intercalation of ferrocene and dimethylaminomethylferrocene into α-Sn(HPO4)2 · H2O and α-VOPO4 · 2H2O. J. Incl. Phenom. 5, 335 (1987).

Liu, Z.-L., Ekuma, C., Li, W.-Q., Yang, J.-Q. & Li, X.-J. Elastool: An automated toolkit for elastic constants calculation. Comput. Phys. Commun. 270, 108180 (2022).

Kastuar, S., Ekuma, C. & Liu, Z.-L. Efficient prediction of temperature-dependent elastic and mechanical properties of 2d materials. Sci. Rep. 12, 3776 (2022).

Liu, Z.-L., Ekuma, C. E. Elastool: A toolkit for elastic and mechanical properties of materials. https://github.com/zhongliliu/elastool (2022)

Qiu, H. et al. Hopping transport through defect-induced localized states in molybdenum disulphide. Nat. Commun. 4, 2642 (2013).

Hong, J. et al. Exploring atomic defects in molybdenum disulphide monolayers. Nat. Commun. 6, 6293 (2015).

Liu, D., Guo, Y., Fang, L. & Robertson, J. Sulfur vacancies in monolayer MoS2 and its electrical contacts. Appl. Phys. Lett. 103 (2013)

Yu, Z. et al. Towards intrinsic charge transport in monolayer molybdenum disulfide by defect and interface engineering. Nat. Commun. 5, 5290 (2014).

Bretscher, H. et al. Rational passivation of sulfur vacancy defects in two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenides. ACS Nano 15, 8780 (2021).

Lifshitz, I. M. The energy spectrum of disordered systems. Adv. Phys. 13, 483 (1964).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE), Office of Science, Basic Energy Sciences (BES), under Award Number DE-SC0024099 (material design), and the U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF) under Award Number DMR-2202101 (TMDCA-BSE code development and first-principles modeling). Computational resources were provided by the Lehigh University high-performance computing infrastructure.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.C.I. wrote the initial manuscript draft, performed first-principles calculations, data curation, and formal analysis. S.M.K. contributed to first-principles calculations, data curation, and formal analysis. G.J. co-developed the many-body code and performed many-body calculations, data curation, and formal analysis. C.E.E. was responsible for the study’s conceptualization and design, conducted formal analysis, provided supervision, validation, and critical revisions, and wrote the final manuscript. All authors reviewed, edited, and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Iloanya, A.C., Kastuar, S.M., Jana, G. et al. Atomic-scale intercalation and defect engineering for enhanced magnetism and optoelectronic properties in atomically thin GeS. Sci Rep 15, 4546 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88290-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88290-z

This article is cited by

-

DFT Investigations of Defect Engineering in GeS Monolayers: Impact on Electronic Structure, Stability, and Optical Properties

Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Electronics (2025)