Abstract

This study aimed to explore the effects of Sufentanil on the cortical neurogenesis of rats with traumatic brain injury (TBI) and investigate the potential mechanisms. Rats with TBI model were prepared and divided into sham + vehicle, TBI + vehicle, TBI + Sufentanil and TBI + Sufentanil + LY294002 (PI3K/AKT signal pathway inhibitor) four groups. The oxidative stress, inflammation, nerve cell damage, melatonin, brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), neuron regeneration and p-AKT protein level in the cortex were detected with ELISA, TUNEL, qRT-PCR, immunofluorescence and Western blot. Pain behavioral test was assessed with mechanical withdrawal threshold (MWT). The results showed Sufentanil significantly decreased the oxidative stress and inflammation levels, increased melatonin and BDNF levels, protected the nerve cells from damage, enhanced the regeneration of immature or mature neurons and the p-AKT protein expression in the cortex, and boosted MWT in TBI rats. While the rats with TBI were treated with LY294002 and Sufentanil together, the abovementioned effects of Sufentanil on the TBI rats were partially reversed. Our results indicate Sufentanil enhances the cortical neurogenesis and inhibits mechanical allodynia of rats with TBI through suppressing the oxidative stress, inflammation response and increasing the melatonin and BDNF levels partly via PI3K/AKT signal pathway.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) involves damage to brain tissue resulting from external mechanical forces applied to the head, potentially causing temporary or permanent impairments in cognitive, physical, and psychosocial functions1. Despite extensive clinical and experimental research by scholars on the pathophysiological mechanisms of TBI, the precise nature of the injury remains unclear, impeding the development of effective clinical treatments2. Its uncertainty contributes significantly to the high mortality and disability rates associated with TBI, imposing substantial economic burdens on society and families. TBI can be categorized into two main phases: initial injury and secondary injury1,3,4,5. Initial injury involves the harm to nerve cells and blood vessels resulting from immediate acceleration and deceleration forces, resulting in brain tissue contusion, intracranial hematoma, edema, diffuse axonal injury, and ischemia. Secondary brain injury refers to the pathological process of persistent changes that occurs in the next few hours to several weeks from the beginning of the injury. The main factors that cause secondary brain damage include: massive release of oxygen free radicals, inflammatory reaction, mitochondrial dysfunction, release of excitotoxic transmitters, and destruction of the blood–brain barrier6. These factors can further aggravate the primary injury, cause severe reduction of cerebral blood flow, cerebral ischemia, hypoxia, and ultimately result in apoptosis and necrosis of nerve cells. Current clinical treatment of TBI is mainly for secondary damage7. Since secondary brain injury takes a long time to occur, minimizing the extent of the injury as much as possible plays a vital role in patient’s outcome. Nonetheless, there remains a scarcity of safe and effective medications designed to mitigate secondary injury, and promote the neurogenesis which may be able to compensate for the dead nerve cells.

Post-TBI pain is a common symptom among patients. Post TBI, acute pain typically arises at the initial injury location and continues through the recovery phase. Persistent chronic pain and neurological dysfunction symptoms may persist, chiefly presenting as chronic pain outside the brain, post-traumatic headaches, sensory irregularities, or mechanical hypersensitivity8,9. Sufentanil is a potent opioid analgesic that primarily acts on the μ-opioid receptor, offering significant pain relief. It is structurally modified from fentanyl, with approximately twice the lipophilicity of fentanyl, making it more readily able to cross the blood–brain barrier. Sufentanil has a higher binding rate to plasma proteins and a smaller distribution volume. Despite its shorter elimination half-life compared to fentanyl, its heightened affinity for opioid receptors leads to increased analgesic efficacy and a prolonged duration of effect. In the management of pain following TBI, sufentanil is capable of rapidly exerting its analgesic effect, effectively relieving the patient’s pain. However, the effect of Sufentanil on the cortical neurogenesis of rats with TBI is still unknown, and this study aimed to explore it and investigate potential mechanisms.

Methods

Animals and groups

The research received approval from the Institutional Ethics Committee of Nanjing Drum Tower Hospital (DwSY-22130259). All experiments and methods were conducted in compliance with the Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments (ARRIVE) guidelines10. We confirmed that all procedures were carried out in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. A total of fifty male Sprague–Dawley (SD) rats weighing between 220 and 250 g were obtained from the Animal Experimental Center of Nanjing Hospital Affiliated to Nanjing Medical University. These rats were randomly assigned to four groups (n = 12): sham + vehicle, TBI + vehicle, TBI + Sufentanil, and TBI + Sufentanil + LY294002 (PI3K/AKT signal pathway inhibitor) groups. Two rats unfortunately died during the modeling process. The rats were maintained with unrestricted access to food and water in an environment set at 22 ± 2 ˚C, with a relative humidity of 50 ± 5% and a 12-h light/dark cycle. Rats were euthanized by deep anesthesia with isoflurane gas.

Rat model preparation and treatment

SD rats in TBI + vehicle group, TBI + Sufentanil group, and TBI + Sufentanil + LY294002 group underwent TBI modeling using a hydraulic controllable injury device (American AmScien Instruments FP302), as described by Yi et al.11. In brief, after anesthesia with isoflurane gas, the rats’ heads were secured on a stereotaxic apparatus. A 5 mm diameter circular bone window was created 3.0 mm to the left of the sagittal suture and 3.5 mm posterior to the bregma, and TBI was induced with a peak impact pressure of 1.5 atm (1 atm = 101.3 kPa). The rats of sham + vehicle group underwent a sham procedure without TBI. All rats were injected intraperitoneally with BrdU (50 mg/kg, twice daily) for five consecutive days to label newborn neurons. After surgery, the rats of TBI + Sufentanil group and TBI + Sufentanil + LY294002 group were administered subcutaneous injection of Sufentanil (5 μg/kg, Nhwa, China) daily for two weeks, while the other groups received an equal volume of sterile saline. The rats of TBI + Sufentanil + LY294002 group were intraperitoneally injected with LY294002 (0.6 mg/kg/d, Sigma, USA) dissolved in DMSO at 30 min before Sufentanil administration, whereas the remaining groups were administered an equivalent volume of DMSO. The dose was chosen based on prior research12,13.

Pain behavior detection

The von Frey test was performed to assess mechanical allodynia at 1, 3, 7, 14 d post-TBI. Prior to testing, rats were habituated to the metal mesh screen for 1 h. The rats’ plantar surfaces were stimulated with a series of von Frey filaments, applying vertical stimuli 5 times, each lasting 2 ~ 3 s. A positive reflex was defined as more than 3 instances of paw withdrawal or licking in response to the stimuli, and the gram force value of the von Frey filament at this point represented the mechanical withdrawal threshold (MWT) of the rat. The MWT with lower values indicated more severe mechanical hyperalgesia. After the detection of pain behavior, the six rats of each group were deeply sedated with isoflurane inhalation, and then fresh brain tissue approximately 2 mm around the injury area was collected for subsequent experiments. The remaining six rats from each group underwent heart perfusion with formalin for fixation, followed by equilibration with sucrose, after which they underwent cryosectioning and the coronal Sects. (15 μm) were mounted on glass slides for further use.

Assessment for oxidative stress, inflammation, melatonin, brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), neurofilament light chain (NEFL) levels

Partial fresh brain tissue was mixed with lysis buffer, centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C, and the supernatant was collected for analysis.

The tissue supernatant was taken for superoxide dismutase (SOD) and malondialdehyde (MDA) level detection by SOD and MDA kits (Beyotime Biotechnology, China), for IL-1β, tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), melatonin and BDNF detection by IL-1β, TNF-α, BDNF ELISA kits (PI303, PT516, PB070, Beyotime Biotechnology, China), melatonin ELISA kit (ab285251, Abcam, UK), and NEFL (a marker for axonal damage) ELISA kit (ab288182, Abcam, UK) a s per the manufacturer’s guidelines.

Nerve cell damage was detected with TUNEL kit

Apoptotic cells in the cortical areas of rat brain sections, located at the front, middle, and rear injury zones, were identified using the TUNEL kit from Beyotime Biotechnology, China, following the manufacturer’s guidelines. Nuclei were then stained with Hoechst 33342 at room temperature for 30 min and examined under a Leica DMR fluorescence microscope at 400 × magnification to observe positive cells.

Neurons regeneration in the cortex was assessed with qRT-PCR, Western blot and immunofluorescence

The Trizol kit from Invitrogen, USA, was employed to extract total RNA from the brain tissue near the injury site. Two micrograms of this RNA were converted into cDNA using Transgen’s reverse transcription reagent (China), following the manufacturer’s instructions. The cDNA served as a template for amplifying doublecortin (DCX), with GAPDH acting as an internal control. Gene expression levels were determined using the 2-△△Ct method. The primer sequences were specified as follows: DCX forward primer 5’-ACTGAATGCTTAGGGGCCTT-3’ and reverse primer 5’-CTGACTTGCCACTCTCCTGA-3’; GAPDH forward primer 5’-TCCCTCAAGATTGTCAGCAA-3’; reverse primer 5’-CACCACCTTCTTGATGTCATC-3’.

A protein extraction kit (Beyotime, China) was used to isolate total protein from the fresh brain tissue near the injury site from six rats in each group. The protein concentration was measured using a BCA kit according to the manufacturer’s guidelines. Following SDS-PAGE, proteins were transferred to a PVDF membrane via wet transfer and blocked with 5% skimmed milk powder for an hour. The membrane was then incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies: rabbit anti-DCX (1:1000, Abcam, UK) or mouse anti-β-actin (1:1000, Abcam, UK). Post washing with TBST, the membrane was treated with secondary antibodies: IRDye 700-conjugated goat anti-mouse or IRDye 800-conjugated goat anti-rabbit (both 1:4000, Rockland Immunochemicals, USA) for two hours at room temperature. Protein expression levels were evaluated using the Odyssey laser scanning system from LI-COR Inc., USA.

Rat brain coronal sections from the front, middle, and rear injury zones were processed for DCX/BrdU or NeuN/BrdU dual immunofluorescence. The sections were first incubated with primary antibodies: mouse anti-NeuN or mouse anti-DCX (both 1:800, Abcam, UK) and rabbit anti-BrdU (1:200, Abcam, UK) for 24 h at 4 °C in a humidified chamber. Subsequently, they were treated with secondary antibodies: Alexa Fluor® 568-labeled goat anti-rabbit and Alexa Fluor® 488-labeled goat anti-mouse (both from Abcam, UK). Nuclei were then stained with Hoechst 33342 at room temperature for 30 min. Positive cells were examined under a fluorescence microscope at 400 × magnification.

The AKT and p-AKT protein levels were detected by Western blot

The AKT and p-AKT protein levels were assessed using Western blot analysis following the procedure described earlier. The primary antibodies used included rabbit anti-AKT (1:800, Abcam, UK), rabbit anti-phospho T308-AKT (1:800, Abcam, UK), and mouse anti-β-actin (1:1000, Abcam, UK). Secondary antibodies consisted of IRDye 700-conjugated goat anti-mouse (1:4000, Rockland Immunochemicals, USA) and IRDye 800-conjugated goat anti-rabbit (1:4000, Rockland Immunochemicals, USA).

Statistical analysis

The study data were processed using SPSS version 21.0, with results displayed as mean ± standard deviation (M ± SD). Group comparison for behavioral assessments used repeated measures two-way ANOVA, other group comparisons utilized one-way ANOVA, subsequently analyzed by Tukey’s test for post-hoc comparisons. Graphical representations were created using GraphPad Prism 7. A significance threshold of P < 0.05 was adopted for all statistical analyses.

Results

Sufentanil suppressed the mechanical allodynia in the rats with TBI

Following TBI, rats in the TBI + vehicle, TBI + Sufentanil, and TBI + Sufentanil + LY294002 groups exhibited a significant decrease in MWT on the first day compared to the sham vehicle group (P < 0.05), with no significant differences between these three groups themselves (P > 0.05). Over time, by the third, seventh, and fourteenth days post-injury, MWT improved slightly but was still notably lower than in the sham + vehicle group (P < 0.05). Notably, at these later stages, rats treated with Sufentanil showed significantly better MWT than those in the TBI + vehicle and TBI + Sufentanil + LY294002 groups (P < 0.05) (Fig. 1).

Sufentanil decreased the oxidative stress and inflammation levels in rats with TBI

Oxidative stress levels of brain tissues around injured area were detected with SOD and MDA kits. Antioxidant ability index SOD level in TBI + vehicle group notably decreased comparison to sham + vehicle group (P < 0.05). While the rats with TBI were treated with Sufentanil, the SOD level was recovered but still lower than in sham + vehicle group (P < 0.05). When rats with TBI were treated by Sufentanil and LY294002 together, the SOD level was similar to TBI + vehicle group (P > 0.05) (Fig. 2A). Oxidative degree index MDA level in TBI + vehicle group notably increased comparison to sham + vehicle group (P < 0.05). While the rats with TBI were treated by Sufentanil, the MDA level was recovered but still higher than in sham + vehicle group (P < 0.05). When rats with TBI were treated with Sufentanil and LY294002 together, MDA level was similar to TBI + vehicle group (P > 0.05) (Fig. 2B).

(A, B) The oxidative stress level was performed with SOD and MAD levels. (C, D) The inflammation response was assessed with IL-1β and TNF-α levels. (E) The BDNF level in cortex. (F) The melatonin level in cortex. * vs. sham + vehicle group, P < 0.05; ^ vs. TBI + vehicle group, P < 0.05; # vs. TBI + Sufentanil group, P < 0.05.

The inflammation levels of brain tissues around injured area were assessed with IL-1β and TNF-α ELISA kits. The IL-1β level in TBI + vehicle group notably increased comparison to sham + vehicle group (P < 0.05). While the rats with TBI were treated by Sufentanil, the IL-1β level was partly recovered but still higher than in sham + vehicle group (P < 0.05). When rats with TBI were treated by Sufentanil and LY294002 together, the IL-1β level was close to that in TBI + vehicle group but lower than that in TBI + vehicle group (P < 0.05) (Fig. 2C). The TNF-α level in the TBI + vehicle group dramatically increased compared with sham + vehicle group (P < 0.05). While rats with TBI were treated by Sufentanil, the TNF-α level was decreased but still higher than in sham + vehicle group (P < 0.05). When rats with TBI were treated by Sufentanil and LY294002 together, the TNF-α level was similar to TBI + vehicle group (P > 0.05), however, no significant statistical difference was observed between the TBI + Sufentanil + LY294002 and TBI + Sufentanil groups (P > 0.05). (Fig. 2D).

Sufentanil increased the BDNF and melatonin levels in rats with TBI

BDNF and melatonin levels in TBI + vehicle group notably decreased comparison with sham + vehicle group (P < 0.05). While rats with TBI were treated with Sufentanil, the BDNF and melatonin levels were recovered but still lower than in sham + vehicle group (P < 0.05). When rats with TBI were treated by Sufentanil and LY294002 together, the BDNF and melatonin levels was similar to TBI + vehicle group (P > 0.05) (Fig. 2E,F).

Sufentanil protected the nerve cells from damage in rats with TBI

The serum NEFL (a marker for axonal damage) level was determined by ELISA kit. The serum NEFL level in TBI + vehicle group dramatically increased comparison to sham + vehicle group (P < 0.05). While rats with TBI were administered by Sufentanil, the serum NEFL level was recovered but still higher than in sham + vehicle group (P < 0.05). When rats with TBI were treated by Sufentanil and LY294002 together, the serum NEFL level was consistent with TBI + Sufentanil group (P > 0.05) (Fig. 3A).

The apoptosis in brain tissues around injured area was detected by TUNEL kit. In the sham + vehicle group, no cells undergoing apoptosis were detected. In contrast, a greater number of apoptotic cells were observed in the TBI + vehicle group. While the rats with TBI were treated by Sufentanil, the percentage of apoptotic cells was significantly decreased but still more than that in sham + vehicle group. When the rats with TBI were treated by Sufentanil and LY294002 together, the percentage of apoptotic cells was similar to TBI + vehicle group (Fig. 3B,C).

Sufentanil enhanced regeneration of immature neurons in cortex of rats with TBI

The mRNA expression of DCX (immature neuron marker) was assessed by qRT-PCR. After TBI, DCX mRNA expression was elevated (P < 0.05). When the rats with TBI were treated with Sufentanil, the DCX mRNA expression was further increased than in TBI + vehicle group (P < 0.05). While the rats with TBI were administered with Sufentanil and LY294002 together, the DCX mRNA level significantly decreased and was like TBI + vehicle group (P > 0.05) (Fig. 4A). DCX protein level was performed by Western blot. In the sham + vehicle group, no DCX protein bands were detected in the rats’ cerebral cortex. Post TBI, DCX protein expression was elevated. When the rats with TBI were treated with Sufentanil, the DCX protein expression was further increased than in TBI + vehicle group (P < 0.05). While the rats with TBI were administered with Sufentanil and LY294002 together, the DCX protein level significantly decreased but was still higher than in TBI + vehicle group (P < 0.05) (Fig. 4B).

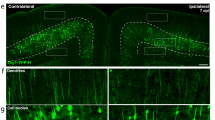

(A) The DCX mRNA was tested by qRT-PCR. (B) The DCX protein was assessed by Western blot. (C) The percentage of DCX+/BrdU+ immature neurons in cortex. (D) The immature neurons in cortex were detected by DCX/BrdU immunofluorescence. * vs. sham + vehicle group, P < 0.05; ^ vs. TBI + vehicle group, P < 0.05; # vs. TBI + Sufentanil group, P < 0.05. Bar = 100 μm.

Neonatal immature neurons in the vicinity of the injury site were identified using dual immunofluorescence for DCX and BrdU. No DCX/BrdU positive cells were observed in the sham + vehicle group, and only a limited number were seen in the TBI + vehicle group. Treatment with Sufentanil in TBI rats resulted in a marked increase in the proportion of DCX/BrdU double-positive cells (P < 0.05). When the rats with TBI were treated by Sufentanil and LY294002 together, the percentage of DCX/BrdU dual positive cells were decreased and similar to TBI + vehicle group (P > 0.05) (Fig. 4C,D).

Sufentanil enhanced regeneration of mature neurons in cortex of rats with TBI

Mature newborn neurons near the injury site were assessed using NeuN and BrdU dual immunofluorescence. The sham + vehicle group showed no NeuN/BrdU positive cells, with a scant presence in the TBI + vehicle group. Treatment of TBI rats with Sufentanil notably elevated the ratio of NeuN/BrdU double-positive cells (P < 0.05); when the rats with TBI were treated with Sufentanil and LY294002 together, the percentage of NeuN/BrdU dual positive cells was similar to TBI + vehicle group (P > 0.05) (Fig. 5A,B).

Sufentanil regulated the PI3K/AKT signal pathway in cortex of rats with TBI

AKT and p-AKT protein levels in brain tissues around injured area were detected by Western blot. The differences of total AKT protein level among sham + vehicle, TBI + vehicle, TBI + Sufentanil and TBI + Sufentanil + LY294002 groups were not statistically significant. Compared with sham + vehicle group, p-AKT protein level in rats with TBI significantly increased; while the rats with TBI were treated by Sufentanil, p-AKT protein level became higher; when rats with TBI were treated by Sufentanil and LY294002 together, the p-AKT protein level decreased and resembled that of TBI + vehicle group (Fig. 6).

Discussion

Both primary brain injury and secondary brain injury can cause irreversible nerve cells, especially neuronal apoptosis and necrosis, which is the basic cause of permanent cognitive, physical and psychosocial disorders14. Campbell et al.15,16 found that dendritic remodeling occurs in the forebrain following traumatic injury. This remodeling may disrupt neuronal circuits, leading to cognitive impairment and other sequelae of TBI. Calcium-sensitive phosphatase calcineurin (CaN) may be involved in the process of dendritic remodeling, and inhibition of CaN might help prevent these sequelae by preserving synaptic circuits following TBI. TBI can activate endogenous neurogenesis. Beyond the recognized neurogenic regions like the hippocampal dentate gyrus (DG) and the subventricular zone (SVZ) adjacent to the ventricles, endogenous neurogenesis also occurs in the cortical region surrounding the injury site11,17,18. Previous study from Yi et al.11 has found there are only a few newborn neurons in the injury cortex after TBI. For neuron loss caused by injury, endogenous neurogenesis without the intervention of external factors is “a drop in the bucket”. In recent years, more and more experimental evidences have shown that Sufentanil demonstrates a neuroprotective effect in cases of brain injury13,19,20. This study showed that Sufentanil enhanced the cortical neurogenesis and inhibited mechanical allodynia of rats with TBI through suppressing the oxidative stress, inflammation response and increasing the melatonin and BDNF levels.

In our study, the results of newborn neurons detection showed after TBI, a few newborn neurons in the injured cortex of rats were also found, and newborn neurons obviously increased when the rats with TBI were treated with Sufentanil. The newborn neurons in the injury cortex of rats without treatment maybe did not survive in the neurogenesis process due to apoptosis which was induced by unfavorable microenvironment after brain injury21. In our study, the results of NEFL level and apoptosis of brain tissue around the injured area showed TBI induced nerve cell damage, while the rats with TBI were administered with Sufentanil, the NEFL level and cellular apoptosis significantly decreased, which indicated Sufentanil had a neuroprotective effect. Some research displays that oxidative stress notably contributes to nerve cell damage in TBI, and causes cerebral ischemia and hypoxia, leading to a significant increase in reactive oxygen species (ROS)22,23. The body’s oxidation and antioxidant capacity are unbalanced, which leads to central neuron lipid peroxidation. Results of our study showed after TBI, the SOD level in the injured cortex decreased and MDA level increased, after Sufentanil treatment, their levels had a certain degree of recovery. After TBI, the inflammatory response is crucial in the pathological process, involving both central nervous system (CNS) resident immunity (like microglia and macrophages) and peripheral immunity (including neutrophils, monocytes, and lymphocytes)24,25. Experimental research confirms that after TBI, the expression of inflammatory mediators around the injury site, including TNF-α, IL-1β, platelet activating factor and IL-6 increased significantly26, which promotes further apoptosis and necrosis of nerve cells, and aggravated tissue damage27. Our results showed after Sufentanil treatment, IL-1β and TNF-α levels in the injured cortex decreased but did not return to the normal levels. Melatonin, a hormone produced by the pineal gland in mammals, and although it is present in low level in the body, its role in health is highly significant. Melatonin can traverse blood–brain barrier, directly affecting brain cells and providing neuroprotective effects. It may protect neurons via various mechanisms, including regulating apoptosis, maintaining intracellular calcium homeostasis, and promoting the repair and regeneration of damaged neurons. Moreover, melatonin, a strong antioxidant, neutralizes body’s free radicals, lessening oxidative stress and safeguarding cells. It also potentially regulates the immune system, affecting immune cell functions and inflammatory responses28,29,30. Our previous results from in vitro neuronal injury model studies have shown that melatonin safeguards neurons from apoptosis by curbing oxidative stress, inflammation, endoplasmic reticulum stress, and mitochondrial damage31. Results of the current study showed that melatonin level significantly decreased in TBI rats, after the addition of Sufentanil, melatonin level obviously elevated. BDNF, a member of the nerve growth factors family, is essential for protecting neurons from damage, including those caused by diseases, injuries, or other harmful factors32,33. BDNF stimulates the differentiation of neural progenitor cells and boosts new neuron production, particularly in the hippocampal DG34. These properties make BDNF a significant target in research for treatment of various neurological diseases. Results of our study displayed that BDNF level significantly declined after TBI, but with Sufentanil treatment, BDNF level then notably increased. The above results indicated that Sufentanil protected nerve cells (including newborn neurons) from damage by reducing oxidative stress, inflammation and increasing the melatonin, BDNF levels. In addition, we used the von Frey test to detect mechanical allodynia of rats and results showed after TBI, mechanical allodynia of rats was significantly enhanced; while the rats with TBI were treated by Sufentanil, the mechanical allodynia was notably restored but still worse than that of the sham + vehicle group.

Studies showed that PI3K/AKT signal pathway is pivotal for the cell survival35, reducing inflammation36 and against oxidative stress37. Our findings showed p-AKT protein level in injured cortex obviously increased after TBI, which suggested the activation of PI3K/AKT signaling pathway in response to injury. When the rats with TBI were treated with Sufentanil, p-AKT protein level in injured cortex obviously elevated, which indicated Sufentanil could regulate PI3K/AKT signal pathway. To further verify it, LY294002 was applied. It is a PI3K/AKT signal pathway inhibitor, and regulates important biological processes such as cell proliferation, survival, and metabolism by inhibiting the activity of PI3K, thereby affecting downstream signaling pathways. When the rats with TBI were treated with Sufentanil and LY294002, and the p-AKT protein level in the injured cortex obviously decreased comparison with TBI rats which were only treated by Sufentanil. At the same time, the abovementioned protective effects of Sufentanil were reversed to a certain extent. The findings indicate that Sufentanil’s effects are at least partially linked to the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway.

However, this study did not conduct further in-depth verification of the upstream and downstream pathways involved in the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. In addition, this study did not observe the involvement of newborn neurons in neuronal circuits. These shortcomings highlight the need for us to conduct more deep-going research in the future.

Conclusion

In summary, our results suggest Sufentanil enhances the cortical neurogenesis and inhibits mechanical allodynia of rats with TBI through suppressing the oxidative stress, inflammation response and increasing the melatonin and BDNF levels partly via PI3K/AKT signal pathway.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Khellaf, A., Khan, D. Z. & Helmy, A. Recent advances in traumatic brain injury. J. Neurol. 266, 2878–2889. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-019-09541-4 (2019).

Sav, A., Rotondo, F., Syro, L. V., Serna, C. A. & Kovacs, K. Pituitary pathology in traumatic brain injury: A review. Pituitary 22, 201–211. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11102-019-00958-8 (2019).

Abdelmalik, P. A., Draghic, N. & Ling, G. S. F. Management of moderate and severe traumatic brain injury. Transfusion 59, 1529–1538. https://doi.org/10.1111/trf.15171 (2019).

Hackenberg, K. & Unterberg, A. [Traumatic brain injury]. Der. Nervenarzt. 87, 203–214; quiz 215–206, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00115-015-0051-3 (2016).

Thapa, K., Khan, H., Singh, T. G. & Kaur, A. Traumatic brain injury: Mechanistic insight on pathophysiology and potential therapeutic targets. J. Mol. Neurosci. 71, 1725–1742. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12031-021-01841-7 (2021).

Wei, W. et al. Alpha lipoic acid inhibits neural apoptosis via a mitochondrial pathway in rats following traumatic brain injury. Neurochem. Int. 87, 85–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuint.2015.06.003 (2015).

Giammattei, L. et al. Current perspectives in the surgical treatment of severe traumatic brain injury. World Neurosurg. 116, 322–328. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2018.05.176 (2018).

Irvine, K. A. & Clark, J. D. Chronic pain after traumatic brain injury: Pathophysiology and pain mechanisms. Pain Med. 19, 1315–1333. https://doi.org/10.1093/pm/pnx153 (2018).

Irvine, K. A., Sahbaie, P., Liang, D. Y. & Clark, J. D. Traumatic brain injury disrupts pain signaling in the brainstem and spinal cord. J. Neurotrauma 35, 1495–1509. https://doi.org/10.1089/neu.2017.5411 (2018).

Kilkenny, C., Browne, W. J., Cuthill, I. C., Emerson, M. & Altman, D. G. Improving bioscience research reporting: The ARRIVE guidelines for reporting animal research. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 20, 256–260. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joca.2012.02.010 (2012).

Yi, X. et al. Cortical endogenic neural regeneration of adult rat after traumatic brain injury. PloS one 8, e70306. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0070306 (2013).

Yong, Y. et al. Electroacupuncture pretreatment attenuates brain injury in a mouse model of cardiac arrest and cardiopulmonary resuscitation via the AKT/eNOS pathway. Life Sci. 235, 116821. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lfs.2019.116821 (2019).

Wang, Z. et al. Sufentanil alleviates cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury by inhibiting inflammation and protecting the blood-brain barrier in rats. Eur. J. Histochem. https://doi.org/10.4081/ejh.2022.3328 (2022).

Lazaridis, C., Rusin, C. G. & Robertson, C. S. Secondary brain injury: Predicting and preventing insults. Neuropharmacology 145, 145–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropharm.2018.06.005 (2019).

Campbell, J. N. et al. Mechanisms of dendritic spine remodeling in a rat model of traumatic brain injury. J. Neurotrauma 29, 218–234. https://doi.org/10.1089/neu.2011.1762 (2012).

Campbell, J. N., Register, D. & Churn, S. B. Traumatic brain injury causes an FK506-sensitive loss and an overgrowth of dendritic spines in rat forebrain. J. Neurotrauma 29, 201–217. https://doi.org/10.1089/neu.2011.1761 (2012).

Brazel, C. Y., Nunez, J. L., Yang, Z. & Levison, S. W. Glutamate enhances survival and proliferation of neural progenitors derived from the subventricular zone. Neuroscience 131, 55–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.10.038 (2005).

Ikeda, T. et al. Limited differentiation to neurons and astroglia from neural stem cells in the cortex and striatum after ischemia/hypoxia in the neonatal rat brain. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 193, 849–856. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2005.01.029 (2005).

Xia, W. & Yang, C. Safety and efficacy of sufentanil and fentanyl analgesia in patients with traumatic brain injury: A retrospective study. Med. Sci. Monit. 28, e934611. https://doi.org/10.12659/MSM.934611 (2022).

Gao, J. et al. Effects of dexmedetomidine vs sufentanil during percutaneous tracheostomy for traumatic brain injury patients: A prospective randomized controlled trial. Medicine 98, e17012. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000017012 (2019).

Otero, L. et al. Endogenous neurogenesis after intracerebral hemorrhage. Histol. Histopathol. 27, 303–315 (2012).

Khatri, N. et al. Oxidative stress: Major threat in traumatic brain injury. CNS Neurol. Disord. Drug Targets 17, 689–695. https://doi.org/10.2174/1871527317666180627120501 (2018).

Ismail, H. et al. Traumatic brain injury: Oxidative stress and novel anti-oxidants such as Mitoquinone and Edaravone. Antioxidants 9, 943. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox9100943 (2020).

Zhou, C. et al. Decreased progranulin levels in patients and rats with subarachnoid hemorrhage: A potential role in inhibiting inflammation by suppressing neutrophil recruitment. J. Neuroinflamm. 12, 200. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12974-015-0415-4 (2015).

Russo, M. V. & McGavern, D. B. Inflammatory neuroprotection following traumatic brain injury. Science 353, 783–785. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaf6260 (2016).

Rana, A., Singh, S., Deshmukh, R. & Kumar, A. Pharmacological potential of tocopherol and doxycycline against traumatic brain injury-induced cognitive/motor impairment in rats. Brain Injury 34, 1039–1050. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699052.2020.1772508 (2020).

Sordillo, P. P., Sordillo, L. A. & Helson, L. Bifunctional role of pro-inflammatory cytokines after traumatic brain injury. Brain Injury 30, 1043–1053. https://doi.org/10.3109/02699052.2016.1163618 (2016).

Wang, Z. et al. Melatonin alleviates intracerebral hemorrhage-induced secondary brain injury in rats via suppressing apoptosis, inflammation, oxidative stress, DNA damage, and mitochondria injury. Transl. Stroke Res. 9, 74–91. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12975-017-0559-x (2018).

Chitimus, D. M. et al. Melatonin’s impact on antioxidative and anti-inflammatory reprogramming in homeostasis and disease. Biomolecules 10, 1211. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom10091211 (2020).

Li, D. et al. Melatonin regulates microglial polarization and protects against ischemic stroke-induced brain injury in mice. Exp. Neurol. 367, 114464. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.expneurol.2023.114464 (2023).

Gu, W., Wu, M., Cui, S., Bo, J. & Wu, H. Melatonin’s protective effects on neurons in an in vitro cell injury model. Discov. Med. 36, 509–517. https://doi.org/10.24976/Discov.Med.202436182.47 (2024).

Gustafsson, D., Klang, A., Thams, S. & Rostami, E. The role of BDNF in experimental and clinical traumatic brain injury. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 3582. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22073582 (2021).

Colucci-D’Amato, L., Speranza, L. & Volpicelli, F. Neurotrophic factor BDNF, physiological functions and therapeutic potential in depression, neurodegeneration and brain cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 7777. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21207777 (2020).

Zhang, K. et al. Hyperactive neuronal autophagy depletes BDNF and impairs adult hippocampal neurogenesis in a corticosterone-induced mouse model of depression. Theranostics 13, 1059–1075. https://doi.org/10.7150/thno.81067 (2023).

Kulik, G., Klippel, A. & Weber, M. J. Antiapoptotic signalling by the insulin-like growth factor I receptor, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, and Akt. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17, 1595–1606. https://doi.org/10.1128/MCB.17.3.1595 (1997).

Chiu, C. H. et al. Erinacine a-enriched Hericium erinaceus mycelium produces antidepressant-like effects through modulating BDNF/PI3K/Akt/GSK-3beta signaling in mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19, 341. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms19020341 (2018).

Li, Q. et al. N-acetyl serotonin protects neural progenitor cells against oxidative stress-induced apoptosis and improves neurogenesis in adult mouse hippocampus following traumatic brain injury. J. Mol. Neurosci.: MN 67, 574–588. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12031-019-01263-6 (2019).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.J. and H.R. designed the study. W.G., M.W., R.Z, and P.L. conducted the experiments and data analysis. W.G. drafted the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Nanjing Drum Tower Hospital Affiliated to Nanjing Medical University (DwSY-22130259).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gu, W., Wu, M., Zhang, R. et al. Sufentanil enhances the cortical neurogenesis of rats with traumatic brain injury via PI3K/AKT signal pathway. Sci Rep 15, 3986 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88344-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88344-2