Abstract

The left atrioventricular coupling index (LACI) evaluates the coupling function between the left atrial (LA) and left ventricular (LV) chambers. However, little is known about LACI in chronic kidney disease (CKD) patients. This study aimed to assess the impact of concurrent CKD and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) on left atrioventricular coupling function compared to CKD patients without T2DM. A retrospective analysis included 173 CKD 4–5 stage patients who underwent echocardiographic examinations. The study comprised 75 CKD patients with T2DM (CKD + DM) and 98 CKD patients without T2DM (CKD-DM). During the follow-up, major adverse cardiac events (MACE) were tracked until June 30, 2024, or death, with a median duration of 21 (18, 27) months, 20.8% of patients experienced MACE, and 10.4% passed away. This study employed speckle tracking echocardiography to evaluate LA and LV strain, alongside the LACI, analyzing its role in predicting MACE. CKD + DM patients showed a notable rise in LACI compared to CKD-DM patients, hinting at a link between diabetes and impaired left atrioventricular coupling in CKD. Patients with lower LACI had superior clinical outcomes during follow-up (P < 0.001). Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses underscored LACI as an independent predictor for heightened MACE risk in CKD 4–5 stage patients. This study highlights a potential association between diabetes and impaired left atrioventricular coupling function in CKD 4-5 stage patients, with LACI independently linked to an increased risk of MACE.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a significant global public health concern, with its prevalence steadily increasing worldwide. Projections indicate that by 2030, CKD will affect 16.7% of adults aged 30 years and older1. Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a well-known risk factor for cardiovascular diseases (CVD) in the general population and is also a major cause of CKD2. Notably, CVD is the primary contributor to mortality in CKD patients, individuals with an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) lower than 30 mL/min/1.73 m2 face an increased risk of CVD development3. The presence of diabetes not only accelerates the progression of CKD but also significantly amplifies the risk of CVD. Consequently, CKD stages 4–5 patients with concomitant diabetes face heightened risks and encounter substantial challenges.

Left ventricular (LV) parameters, including left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), strain, and global function index (LVGFI), have prognostic value in predicting cardiovascular disease (CVD)4,5,6. However, impaired LV structure and function alone do not fully explain CVD occurrence7. Even with preserved LV systolic function, left atrial (LA) dysfunction can negatively affect overall cardiac function, leading to cardiac dysfunction8. Notably, the LA and LV are anatomically connected during ventricular diastole, and their function and filling pressures are closely intertwined in the absence of mitral valve stenosis9,10.

LACI, calculated as the ratio of LA to LV volumes at end-diastole, was initially investigated in a large cohort of CVD-free patients11. This index introduces a novel parameter for evaluating cardiac function, addressing the limitations of conventional measures. Although some studies have assessed cardiovascular risk in individuals with both CKD and diabetes12, the evaluation of left atrioventricular coupling function impairment in this specific population remains limited. Hence, this study aims to assess left atrioventricular coupling function impairment in patients with CKD and concurrent DM by utilizing the LACI measured through echocardiography.

Methods

Study population

A total of 214 patients in CKD 4-5 stages between June 2021 and June 2024 were included in the study. The diagnosis and staging of CKD were conducted in accordance with the Clinical Practice Guidelines for Chronic Kidney Disease13. These patients demonstrated sinus rhythm during their echocardiographic evaluations. Exclusion criteria Cardiomyopathies (diseases causing left ventricular wall thickening such as hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, Fabry disease, cardiac amyloidosis, etc.), myocardial infarction, and coronary artery atherosclerosis. Additionally, significant valvular heart diseases (at least mild valve stenosis, moderate or severe aortic or mitral regurgitation, severe pulmonary or tricuspid regurgitation), congenital heart diseases, and individuals unable to cooperate with echocardiographic examinations or with poor image quality were excluded.

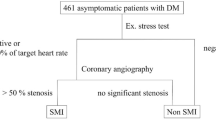

Finally, A total of 173 CKD patients met the inclusion criteria and were included in the analysis. They were categorized into two groups based on the presence or absence of DM, the CKD-DM group (n = 98) and the CKD + DM group (n = 75) (Fig. 1). The diagnosis of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) was established according to the guidelines provided by the American Diabetes Association or the use of antidiabetic medications14. The clinical endpoint in this study is the occurrence of MACE, a composite outcome encompassing all-cause mortality or hospitalization due to heart failure. Hospitalization for heart failure is specifically defined as admission necessitated by heart failure symptoms that mandate intravenous diuretic therapy. The methods employed in this study were conducted in strict adherence to applicable guidelines and regulations. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Guizhou Medical University Affiliated Hospital (Ethics Approval No: [2021] Ethics Approval Department 318). It was conducted as a retrospective study, and informed consent was waived.

Data collection of demographics and laboratory measurements

Relevant demographic information, encompassing age, gender, height, weight, body surface area (BSA), systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP), smoking history, alcohol consumption history, and diabetes history, dialysis history, and stage of CKD was meticulously retrieved from the patients’ medical records. The collection of laboratory data involved the assessment of cardiac biomarkers, including Troponin T, Myoglobin, and N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP). Additionally, renal function indicators, such as Urea, Creatinine, Uric acid, Cystatin C, and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), were also included.

Echocardiography

The echocardiographic assessment was conducted using the Philips EPIQ7C and Philips EPIQCVx color Doppler ultrasound systems, equipped with an X5-1 transducer (frequency range: 1–5 MHz). Acquire high-quality and dynamic DICOM images of the apical four-chamber, three-chamber, and two-chamber views of the heart in accordance with the guidelines15, Data were obtained by averaging measurements from five consecutive stable cardiac cycles, then store them on the hard drive. A comprehensive analysis of echocardiographic parameters, including two-dimensional imaging, doppler measurements, and tissue doppler assessments, was performed by experienced sonographers with a minimum of 10 years of expertise. The following key parameters were measured: left ventricular end-diastolic diameter (LVEDD), left ventricular end-diastolic volume (LVEDV), LVEF, left ventricular mass (LVM), left atrial anteroposterior diameter (LAD), left atrial end-diastolic volume (LAEDV), interventricular septum (IVS) and left ventricular posterior wall (LVPW) thickness, early and late diastolic peak velocities across the mitral valve (E, A), mean velocities of early diastolic septal and lateral mitral annular motion (e′), calculated E/A ratio, E/e′ ratio, LVMI and LAEDVI were derived by normalizing the measurements with respect to the BSA.

Subsequently, 2D speckle tracking imaging (2D-STI) was performed. LA and LV views were acquired with appropriate image magnification in the apical four-chamber view. Automated myocardial motion tracking and region of interest (ROI) generation were conducted using the QLAB 13 quantitative analysis software. The software automatically derived several temporal strain values for the LA and LV, including left atrial reservoir strain (LASr), left atrial conduit strain (LAScd), left atrial contraction strain (LASct) and left ventricular global longitudinal strain (LVGLS). The left atrial stiffness index (LASI) was calculated as E/e′/LASr, and LACI was determined as LAEDV/LVEDV. Measurements of LA and LV volumes were obtained at the same diastolic phase. A higher LACI indicates a greater disparity between LV volume and LA volume at end-diastole, which reflects a more significant impairment in left atrioventricular coupling11.

Reproducibility analysis

To assess the variability within and between observers, a randomized sample of 10 subjects was selected from each study group. Two ultrasound physicians, each possessing more than 10 years of professional experience, independently conducted measurements of LA and LV strain, LVEDV, LAEDV for the selected subjects. Following a two-week interval, the same ultrasound physicians reexamined the selected cases. Intra-observer variability was evaluated by utilizing the two sets of measurements obtained by the first investigator, whereas inter-observer consistency was assessed based on the results derived from the two physicians.

Statistical analysis

Categorical data in this study were presented as frequencies (%). Group comparisons were conducted using the chi-square test. The normality of continuous variables was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Normally distributed continuous variables were reported as mean ± standard deviation (SD), while non-normally distributed variables were presented as median (interquartile range). Group comparisons of continuous variables were performed using independent-samples t-test or Mann-Whitney U test, as appropriate. Spearman’s correlation coefficient was utilized to evaluate the correlation between clinical and ultrasound parameters in CKD patients. Multiple linear regression analysis was conducted to evaluate the factors influencing the LACI. Variables that demonstrated significance (p < 0.05) in the univariate analysis were included in the multivariate model, with a variance inflation factor of 5 applied to mitigate multicollinearity. The Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve was utilized to compute the area under the curve (AUC), determining the optimal LACI cut-off value for MACE prediction. Kaplan-Meier survival curves and log-rank tests were used to compare event-free survival rates between patients with high and low LACI values. A multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression model was utilized to identify independent predictors of MACE, encompassing covariates that were statistically significant or clinically relevant in the univariate analysis, with outcomes expressed as hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals. Intra-observer and inter-observer variability of LASr, LAScd, LASct, LVGLS, LAEDV, and LVEDV were evaluated using the Interclass Correlation Coefficients (ICC). Statistical analysis was conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics 25.0 software. A two-tailed p-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. GraphPad Prism software (version 8.0) was used to draw the heat map, ROC curve and the Kaplan-Meier survival curves.

Results

Comparison of clinical characteristics between the CKD + DM and CKD-DM groups

Compared to the CKD-DM group, patients in the CKD + DM group demonstrated several notable distinctions. They had a higher mean age, a greater proportion of males, elevated BMI and BSA values, a higher prevalence of hypertension, and a higher frequency of smoking and alcohol consumption. Additionally, the CKD+DM group exhibited significantly higher levels of troponin T, NT-proBNP, and blood glucose. These differences were found to be statistically significant (all p < 0.05). Conversely, there were no substantial differences observed between the two groups regarding myoglobin, CKD stage, dialysis, urea, serum creatinine, uric acid, and cystatin C levels (Table 1).

Comparison of ultrasound parameters between the CKD + DM and CKD-DM groups

Compared to the CKD-DM group, the CKD + DM group demonstrated elevated levels of LACI, LAEDVI and LASI. Furthermore, LVGLS, LASr, LAScd and LASct were deteriorated, although the difference in LVMI was not statistically significant (Table 2 and Fig. 2). Moreover, the CKD+DM group exhibited significantly higher values of LAEDV, LAD, A, and E/e′ ratio. Conversely, the e′ and E/A were lower in the CKD + DM group. These differences were statistically significant (p < 0.05). There were no significant differences observed between the two groups in terms of LVEDV, LVEF, LVM, LVEDD, IVS, LVPW, and E(p > 0.05) (Table 2).

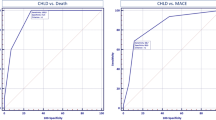

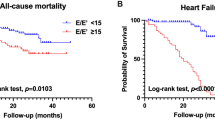

Correlation analysis

The correlation analysis revealed a significant positive correlation between LACI and LAEDVI (r = 0.853, p < 0.001), while no significant correlation was observed between LACI and LVGLS (r = 0.083, p = 0.279) serum creatinine (r = 0.101, p = 0.187) and cystatin C (r = 0.065, p = 0.396) (Fig. 3). Univariate analysis indicated significant associations between LACI and history of DM, ln NT-proBNP, E/e′, LASr, and LAScd. Subsequently, the significant variables identified in the univariate analysis were included in the multivariate analysis. The multivariate analysis revealed that DM independently contributed to an increased risk of LACI in CKD patients (β = 0.299, p < 0.001) (Table 3). In the ROC analysis, the optimal cutoff value for LACI to predict MACE was established at 0.240, with an area under the curve of 0.830 (Fig. 4). Kaplan-Meier analysis revealed a notably lower event-free survival rate among patients with elevated LACI compared to those with lower LACI levels (log-rank test P < 0.001) (Fig. 5). In the multivariate Cox regression analysis, an escalation in LACI was independently linked to an increased risk of MACE, whereas no significant correlation was observed between LVGLS and LASI (Table 4).

Heatmap illustrating the relationship between clinical and ultrasound parameters in CKD patients. The color shading in each cell represents the magnitude and direction of the correlation coefficient, wherein red indicates a positive correlation and white indicates a negative correlation. The numerical values within the cells denote the correlation coefficients.

Reproducibility analysis

Table 5 presents the variabilities of LA strain, LVGLS, LVEDV, and LAEDV among observers. Intra-observer ICC for LA strain ranged from 0.97 to 0.983, and inter-observer ICC ranged from 0.912 to 0.949. For LVGLS, the intra-observer ICC was 0.980 and inter-observer ICC was 0.920. Intra-observer ICC for LVEDD was 0.967, and inter-observer ICC was 0.908. LAEDV showed an intra-observer ICC of 0.971 and an inter-observer ICC of 0.935.

Discussion

Our study represents a pioneering investigation utilizing the left atrioventricular coupling index to assess cardiac function in patients with concurrent CKD 4–5 stage and T2DM. Our findings can be summarized as follows: CKD + DM patients display elevated E/e′ values and more pronounced impairments in LVGLS, LASr, LAScd and LASct, suggesting compromised LV systolic and diastolic function despite normal LVEF in both groups, accompanied by reduced LA reservoir, conduit, and contractile function. Additionally, compared to CKD-DM, CKD + DM patients exhibit significantly higher LACI levels. Univariate and multivariate analyses confirm the independent association between DM and increased LACI, reinforcing the connection between diabetes and impaired left atrioventricular coupling. Finally, our results indicate that LACI serves as an independent predictor of heightened MACE risk in CKD patients, with individuals having higher LACI values showing lower event-free survival rates than those with lower LACI levels.

CKD commonly coexists with multi-system dysfunctions, where anomalies in cardiac structure and function serve as significant predictors of adverse clinical outcomes16. Echocardiography is advised for detecting and monitoring alterations in cardiac anatomy and function among CKD patients. Diabetes is a significant contributor to the development of CKD worldwide. Based on data from the US Renal Data System (USRDS) in 2023, the prevalence of diabetes among CKD patients was 35.6%17. Importantly, individuals with CKD, especially those with diabetes, are at an increased risk of cardiovascular events even before reaching end-stage kidney disease (ESKD), possibly due to microvascular impairments. Fox et al.18 observed heightened rates of cardiovascular and all-cause mortality in patients with diabetes compared to their non-diabetic counterparts. Vejakama et al.19 documented that the individuals with diabetes experience kidney failure at a twofold accelerated rate relative to non-diabetic individuals. Furthermore, Tonelli et al.20 ascertained that the coexistence of diabetes and CKD is associated with escalated incidence rates of myocardial infarction (MI) and all-cause mortality when compared to the presence of diabetes alone.

Within the cardiovascular system, the LA assumes a vital role in orchestrating LV filling and cardiac output throughout the cardiac cycle21. The dimensions and functionality of the LA serve as informative indicators of overall cardiac performance, independent of LV function8,22. Our study indicates that CKD + DM patients exhibit a larger LAD. LA enlargement represents an adaptive response of the LA in the context of comorbid CKD and DM. Persistent hyperglycemia and increased hemodynamic burden in CKD + DM patients have been shown to have negative effects on the cardiovascular system. The LA enlargement may serve as a compensatory mechanism to meet the increased demands of cardiac workload. LA serves as a conduit connecting the pulmonary veins to the LV and influences LV filling through its reservoir function (LASr), conduit function (LAScd), and pump function (LASct)23. Extensive research across various cohorts, including heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF), and individuals without heart failure, consistently demonstrates the predictive value of LA function24. These studies consistently establish that LA reservoir and conduit function, rather than LA contraction function, are closely associated with heart failure hospitalization and mortality events24. Our findings indicated that CKD+DM patients, when compared to CKD-DM patients, not only exhibit poorer performance in LASr and LAScd, but also demonstrate a reduction in the absolute value of LASct, coupled with higher LASI values. This points towards a deterioration in left atrial reservoir, conduit, and contractile functions among individuals with both CKD and DM, contributing to reduced left atrial compliance and increased stiffness. However, it should be noted that these observations are specific to patients in CKD 4–5 stage. Moreover, in CKD patients, both LV systolic and diastolic functions are compromised. Lang et al.25 substantiated that LVGLS exhibits greater sensitivity in predicting overall mortality and cardiovascular events compared to LVEF. Farshid et al.26 identified LV diastolic function as a robust independent predictor of mortality. Morris et al.27 noted that LVGLS and LA strain are significantly diminished in patients with preserved LVEF compared to asymptomatic controls, with LVGLS closely associated with LA strain in systole and diastole. Mochizuki et al.28 proposed that impaired LVGLS results in diminished traction of the LV base during systole, leading to insufficient LA pull towards the apex. Furthermore, LV pressure, serving as the LA’s afterload, influences the interplay between LA contraction and LV pressure, playing a pivotal role in the smooth passive stretching of the LA during late diastole.

While the prognostic importance of LV and LA parameters in predicting heart failure and MACE is recognized, analyzing alterations in the LA-LV cardiac interdependence may provide a more comprehensive grasp of left heart function. Introducing a novel metric of left atrioventricular coupling, termed the LACI, aims to clarify the physiological correlation and prognostic implications between the LA and LV. LACI is calculated as the ratio of LA volume to LV volume, with lower values indicating a more efficient coupling between the LA and LV at end-diastole29. Demonstrating robust predictive abilities for MACE, LACI is viewed as a potential substitute for individual LA and LV functional and structural parameters in terms of prognostic value11. Moreover, in contrast to traditional risk factors and LA parameters, LACI has been found to correlate with myocardial fibrosis and exhibits superior predictive accuracy for new-onset atrial fibrillation30,31,32. Our investigations also highlight a robust connection between LACI and MACE, surpassing LASI and LVGLS in predictive power. Previous research has hinted at a potential relationship between LACI and hormone levels, which could influence left atrioventricular coupling33. Nevertheless, our findings did not uncover a significant association between gender and LACI. It is noteworthy that we observed heightened LACI values in individuals with both CKD and concurrent T2DM, with diabetes identified as an independent factor influencing LACI. This finding hints at a plausible link between increased LACI and T2DM in CKD patients. In cases where CKD and T2DM coexist, elevated levels of creatinine and blood glucose can detrimentally affect myocardial cells, resulting in varying degrees of impairment in LA and LV function. LACI functions as a parameter for evaluating the left atrioventricular ratio, a change that may not be adequately captured by deteriorations in isolated LA and/or LV strains.

The LACI was initially introduced in a study involving diverse populations without cardiovascular disease, utilizing magnetic resonance imaging data11. Pezel et al. further substantiated an independent correlation between compromised left atrioventricular coupling index assessed through cardiac CT and the incidence of cardiovascular mortality34. However, the accessibility of cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMR) or computed tomography (CT) scans remains restricted in routine clinical practice, particularly for primary prevention patients. Transthoracic echocardiography, a widely employed and non-invasive cardiac imaging technique, has been leveraged in evaluating left atrioventricular coupling function, as exemplified by Meucci et al. in their investigation of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy32. Moreover, given the dimensionless quality of LACI and its minimal post-processing demands, LACI stands out as an appealing parameter with substantial diagnostic and prognostic implications. In this regard, the utilization of AI-driven post-processing software algorithms could potentially standardize and refine volume analysis, as evidenced by the findings of Pezel et al.‘s study35. It is crucial to acknowledge that the concept and physiological mechanisms underlying left atrioventricular coupling are intricate, and while LACI holds value, it may not encapsulate the entirety of the complexities associated with left atrioventricular coupling, underscoring the need for further validation in future research endeavors.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. Firstly, being a retrospective and single-center study, inherent selection bias may exist. Secondly, the limited sample size resulting from the absence of DICOM images for some patients restricted further analysis. Thirdly, we solely conducted intergroup comparisons for dialysis without delving into more detailed subgroup analyses, and omitted considerations of the course and treatment of diabetes, thus limiting the generalizability of the conclusions. Fourthly, although we monitored the clinical outcomes of patients, the relatively short follow-up period may have impacted the results. Lastly, in the COX regression analysis, the wide confidence interval of ln LACI could be attributed to the small sample size and short follow-up duration, potentially affecting the precision of the results. Future studies will encompass larger sample sizes, explore subgroups of dialysis, diabetes progression, and treatments, and undertake extended monitoring of clinical outcomes in CKD patients to more robustly validate our findings.

Conclusion

In CKD 4–5 stage patients with T2DM, LVGLS, LASr, LAScd and LASct are more impaired. LACI is a valuable tool for assessing cardiac function in these patients, with lower values correlating with improved event-free survival rates. Diabetes independently raises LACI, suggesting altered left atrioventricular coupling in this population. Moreover, LACI independently predicts MACE in CKD 4–5 stage patients.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Hansrivijit, P. et al. Prediction of mortality among patients with chronic kidney disease: A systematic review. World J. Nephrol. 10(4), 59–75 (2021).

Alicic, R. Z., Rooney, M. T. & Tuttle, K. R. Diabetic kidney disease: Challenges, Progress, and possibilities. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 12 (12), 2032–2045 (2017).

Chatur, S. et al. Sacubitril/valsartan in patients with heart failure and deterioration in eGFR to <30 mL/min/1.73 m2. JACC Heart Fail. 12(10), 1692–1703 (2024).

Yeboah, J. et al. Prognosis of individuals with asymptomatic left ventricular systolic dysfunction in the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis (MESA). Circulation 126(23), 2713–2719 (2012).

Al Saikhan, L., Park, C., Hardy, R. & Hughes, A. Prognostic implications of left ventricular strain by speckle-tracking echocardiography in population-based studies: A systematic review protocol of the published literature. BMJ Open 8(7), e023346 (2018).

Mewton, N. et al. Left ventricular global function index by magnetic resonance imaging–a novel marker for assessment of cardiac performance for the prediction of cardiovascular events: The multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Hypertension 61(4), 770–778 (2013).

Triposkiadis, F. et al. Global left atrial failure in heart failure. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 18(11), 1307–1320 (2016).

Hoit, B. D. Left atrial size and function: Role in prognosis. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 63(6), 493–505 (2014).

Bowman, A. W. & Kovács, S. J. Left atrial conduit volume is generated by deviation from the constant-volume state of the left heart: A combined MRI-echocardiographic study. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 286(6), H2416–H2424 (2004).

Barbier, P., Solomon, S. B., Schiller, N. B. & Glantz, S. A. Left atrial relaxation and left ventricular systolic function determine left atrial reservoir function. Circulation 100(4), 427–436 (1999).

Pezel, T. et al. Left atrioventricular coupling index as a prognostic marker of cardiovascular events: The MESA Study. Hypertension 78(3), 661–671 (2021).

Ruhe, J. et al. Cardiovascular risk due to diabetes mellitus in patients with chronic kidney disease-prospective data from the German chronic kidney disease cohort. Clin. Kidney J. 16(11), 2032–2040 (2023). Published 2023 Sep 1.

Stevens, P. E., Levin, A. & Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes Chronic Kidney Disease Guideline Development Work Group Members. Evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease: Synopsis of the kidney disease: Improving global outcomes 2012 clinical practice guideline. Ann. Intern. Med. 158(11), 825–830 (2013).

Chamberlain, J. J., Rhinehart, A. S., Shaefer, C. F. & Neuman, A. Diagnosis and management of diabetes: Synopsis of the 2016 American Diabetes Association Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes. Ann. Intern. Med. 164(8), 542–552 (2016).

Mitchell, C. et al. Guidelines for performing a comprehensive transthoracic echocardiographic examination in adults: Recommendations from the American Society of Echocardiography. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 32(1), 1–64 (2019).

Glassock, R. J., Pecoits-Filho, R. & Barberato, S. H. Left ventricular mass in chronic kidney disease and ESRD. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 4(Suppl 1), S79–S91 (2009).

United States Renal Data System. USRDS Annual Data Report: Epidemiology of Kidney Disease in the United States (National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, 2023). (2023).

FoxCS et al. Associations of kidney disease measures with mortality and end-stage renal disease in individuals with and without diabetes: A meta-analysis [published correction appears in Lancet. 2013;381(9864):374]. Lancet 380(9854), 1662–1673 (2012).

Vejakama, P., Ingsathit, A., Attia, J. & Thakkinstian, A. Epidemiological study of chronic kidney disease progression: A large-scale population-based cohort study. Medicine 94 (4), e475 (2015).

Tonelli, M. et al. Risk of coronary events in people with chronic kidney disease compared with those with diabetes: A population-level cohort study. Lancet 380 (9844), 807–814 (2012).

Debonnaire, P. et al. Left atrial size and function in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy patients and risk of New-Onset Atrial Fibrillation. Circ. Arrhythm. Electrophysiol. 10 (2), e004052 (2017).

Raisi-Estabragh, Z. et al. Left atrial structure and function are associated with cardiovascular outcomes independent of left ventricular measures: A UK Biobank CMR study [published correction appears in Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2022]. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 23(9), 1191–1200 (2022).

Fu, Y. & Liu, X. The value of left atrial temporal function in diagnosing left ventricular diastolic dysfunction in patients with coronary atherosclerotic heart disease. J. Clin. Ultrasound 25(1), 39–43 (2023).

Chirinos, J. A. et al. Left atrial phasic function by cardiac magnetic resonance feature tracking is a strong predictor of incident cardiovascular events. Circ. Cardiovasc. Imaging 11(12), e007512 (2018).

Lang, R. M. et al. Recommendations for cardiac chamber quantification by echocardiography in adults: An update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 28 (1), 1–39 (2015).

Farshid, A., Pathak, R., Shadbolt, B., rnolda, L. & Talaulikar, G. Diastolic function is a strong predictor of mortality in patients with chronic kidney disease. BMC Nephrol. 14, 280 (2013). Published 2013 Dec 23.

Morris, D. A. et al. Left atrial systolic and diastolic dysfunction in heart failure with normal left ventricular ejection fraction. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 24(6), 651–662 (2011).

Mochizuki, Y. et al. Impaired mechanics of left ventriculo-atrial coupling in patients with diabetic nephropathy. Circ. J. 80(9), 1957–1964 (2016).

Germans, T. et al. Effects of aging on left atrioventricular coupling and left ventricular filling assessed using cardiac magnetic resonance imaging in healthy subjects. Am. J. Cardiol. 100 (1), 122–127 (2007).

Pezel, T. et al. Determinants of left atrioventricular coupling index: The multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis (MESA). Arch. Cardiovasc. Dis. 115(8–9), 414–425 (2022).

Pezel, T. et al. Change in left atrioventricular coupling index to predict incident atrial fibrillation: The multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis (MESA). Radiology 303(2), 317–326 (2022).

Meucci, M. C. et al. Left atrioventricular coupling index in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and risk of new-onset atrial fibrillation. Int. J. Cardiol. 363, 87–93 (2022).

Pezel, T. et al. Prognostic value of a left atrioventricular coupling index in pre- and post-menopausal women from the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 9, 1066849 (2022).

Pezel, T. et al. Left atrioventricular coupling index assessed using cardiac CT as a prognostic marker of cardiovascular death. Diagn. Interv. Imaging 104(12), 594–604 (2023).

Pezel, T. et al. AI-based fully automated left atrioventricular coupling index as a prognostic marker in patients undergoing stress CMR. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 16(10), 1288–1302 (2023).

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82260074), Guizhou Provincial Science and Technology Program (Qiankehe foundation-ZK [2023] General 373) and Guizhou Medical University Affiliated Hospital Doctoral Research Start-up Fund Project (gyfybsky-2021-19).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.G., AH.X. and W.X. wrote the main manuscript. S.Y. and S.Y.Y. revised the manuscript. The remaining authors contributed to data collection. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.X.G., AH.X. and W.X. share equal contribution as co-first authors. S.Y. is the corresponding author, SY.Y. is the co-corresponding author.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Informed consent

Informed consent was waived by the Ethics Committee of Guizhou Medical University Affiliated Hospital (Ethics Approval No: [2021] Ethics Approval Department 318).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gao, X., Xie, A., Xiao, W. et al. A novel index evaluating left atrioventricular coupling function in chronic kidney disease with diabetes patients. Sci Rep 15, 8402 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88402-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88402-9