Abstract

Cognitive and visual impairment are common in Huntington’s Disease (HD) and may precede motor diagnosis. We investigate the early presence of visual cognitive deficits in 181 participants, including HD carriers (40 pre-manifest, 30 early manifest, 27 manifest, and 6 reduced penetrance) and 78 healthy controls (HC). Significant differences in visual memory were observed between reduced penetrance and pre-manifest groups (p = .003), with pre-manifest showing worse performance. Age, education, CAG repeats, motor status, executive function, and verbal fluency, accounted for up to 72.8% of the variance in general and visual cognitive functions, with motor status having the strongest impact on visual domains in HD carriers. In pre-manifest HD, visual cognitive domains were primarily influenced by executive function, verbal fluency, age, and CAG repeats, while in early and manifest stages motor status and verbal fluency becomes more influential. ROC analyses showed that especially visuospatial abilities, visual memory, and visual attention (AUC = 0.927, 0.878, 0.874, respectively) effectively differentiated HC and pre-manifest from early and manifest HD. Early assessment of visual cognitive domains, particularly visual memory, could be an early marker of cognitive decline in HD. Our findings highlight the different profiles of impairment in visual cognition across HD carriers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Huntington’s Disease (HD) is a rare, autosomal dominant neurodegenerative disorder caused by an expansion of cytosine-adenine-guanine (CAG) repeats (> 35 repeats) in the Huntingtin (HTT) gene1,2. HD primarily manifests as an adult-onset disorder3, and is characterized by a complex symptomatology involving progressive motor and cognitive impairment, along with psychiatric symptoms, due to neuronal loss in the brain2,4. The diagnosis relies primarily on the presence of motor symptoms; however, non-motor symptoms may appear before clinical diagnosis. The number of CAG repeats is the primary factor determining the rate of striatal pathology progression, with individuals having 40 or more CAG repeats developing HD during their lifetime. Studies have also identified a range of 36–39 CAG repeats, referred to as “reduced or incomplete penetrance” alleles, where symptoms may appear later in life or not at all5,6. However, the factors contributing to this variability remain unclear, and prior studies have been unable to precisely estimate the penetrance risk7. Individuals with 40 or more CAG repeats who do not yet meet the clinical criteria for HD are often referred to as pre-symptomatic or pre-manifest HD8,9.

Currently, there is no cure for HD, and the disease typically progresses over 15–20 years from onset, with diagnosis primarily based on motor impairment1,10. However, recent literature increasingly suggests that the onset of movement disorder alone does not fully represent the spectrum of HD. The symptoms are complex and vary significantly among CAG expansion carriers, introducing uncertainty regarding the appearance of specific signs, age of onset2, and disease severity11.

Cognitive impairment and visual abnormalities are common and functionally debilitating in HD gene carriers2,8,12, and often appear before HD motor diagnosis10. In fact, retinal thickness has potential as a good biomarker of cognitive impairment in manifest HD, with a reduction of peripapillary retinal nerve fiber layer thickness observed regardless of disease stage13,14,15. In terms of cognition, HD-related decline primarily involves progressive impairment in executive function16,17,18, which is associated with reduced functional capacity and, consequently, a decline in quality of life. As well as deficits in attention and concentration, worsened working memory, slowed psychomotor speed, language deficits and impaired language skills. Social cognition is also affected, leading to challenges in understanding and interpreting social cues, emotions, and relationships19. Executive dysfunction in HD also includes impairments in attention, initiating and planning activities, organizational skills, problem-solving, decision-making, and cognitive flexibility, ultimately leading to difficulties in managing daily life activities16. Individuals with HD often face challenges in starting and completing complex tasks, managing their time, and organizing their thoughts. They may also struggle with accurately assessing risks, leading to poor decision-making19. The degree and progression of cognitive impairment in HD can vary among individuals, but cognitive decline is generally observed over time as the neurodegeneration associated with HD advances. Cognitive impairment can appear 10 to 15 years prior to the onset of motor symptoms20, and there is increasing evidence that deficits in visual cognitive domains may serve as early indicators of cognitive decline in HD. This highlights the importance of recognizing and assessing these visual cognitive impairments, which can precede the clinical diagnosis of HD and significantly affect gene carriers. However, the term ‘visual cognition’ is rarely used and not well-defined21. Visual cognition encompasses complex mental processes engaged in interpreting, analysing, and comprehending visual information from our surroundings. Visual cognition is essential for the formation of mental representations of the visual environment and for the extraction of significant information from visual stimuli22,23. It encompasses various cognitive functions, including: visual attention (the ability to focus on specific visual information while filtering out distractions); visual perception (the ability to recognize and interpret visual stimuli, such as shapes, colors, and motion); visual memory (retain and recall visual information, which can include visual images, spatial relationships, and patterns); visuospatial abilities (understanding the location and movement of objects in relation to oneself and each other); visual problem-solving (using visual information to analyze situations, make decisions, and solve problems). Therefore, visual cognition plays a crucial role in how individuals interact with and understand their visual environment, influencing activities such as reading, navigating spaces, and recognizing faces.

Neuropsychological studies assessing visual cognitive function in HD have reported impairments in several structures and networks involved in the key steps of visual information perception and processing. Specifically, these studies have identified deficits in tasks related to visual object perception, facial emotion recognition, visuospatial processing, and visual working memory22,24. Changes in the visual cortex and visual cognitive deficits have been reported in early manifest HD gene carriers, but not in pre-manifest gene carriers25. Although, cognitive decline is a well-known non-motor symptom of HD associated with reduced functional capacity—interfering with patients’ work and social lives and subsequently worsening their quality of life—further research is needed to understand visual cognitive impairments in pre-manifest HD. It is essential to identify which specific cognitive areas are most affected in this population. Exploring visual cognition also in the reduced penetrance range is particularly important, as it may provide insights into the risk of pheno-conversion26. This information can enhance genetic counseling and inform therapeutic options when they become available. We aimed to investigate the early presence of visual cognitive deficits in HD carriers across the entire spectrum, including pre-manifest, early manifest, manifest HD, and participants with reduced penetrance, compared to healthy controls (HC).

Methods

Study design and Participant

A total of 181 participants were recruited, divided into 5 groups: 40 pre-manifest HD, 30 early manifest HD (disease duration < 5 years from the diagnosis), 27 manifest HD (disease duration > 5 years from the diagnosis), 6 with reduced penetrance (CAG repeat range of 36–39 CAG), and 78 HC. Study subjects were mainly recruited in the Department of Neurology of Cruces University Hospital, but also in Araba University Hospital and Donostia University Hospital (Spain). The HC group was recruited through word of mouth, the Huntington’s Disease Association of Bizkaia (ASHUBI), and family and friends of patients who did not carry pathological CAG repeats.

The inclusion criteria were the following: (1) Age > 18 years; (2) Voluntary participation and signing the informed consent from; (3) Being able to read and write; (4) In the case of genetic carriers, having a genetic test that indicates the number of CAG repeats; (5) Classification of participants as pre-manifest (no clinical-motor HD diagnose but a positive genetic test), early manifest (disease duration < 5 years from the diagnosis), manifest HD patients (disease duration > 5 years from the diagnosis), and reduced penetrance group (CAG repeat range of 36–39). The exclusion criteria were as follows (1) Previous history of physical or mental disease that significantly compromised the cognitive function of the patient; (2) Visual or hearing limitation that could not be compensated with glasses or hearing aids; (3) Significant history of alcohol or drugs abuse; (4) Lack of will or incapacity of the participant to collaborate with the study.

Clinical and neuropsychological assessment

The clinical evaluation protocol consisted of measuring: (1) Motor status with the Unified Huntington’s Disease Rating Scale (UHDRS)27; (2) Cognitive general status with the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA)28,29; (3) Visual Attention with Stroop Test (Word, Color, Word-Color)30and Trail Making Test (TMT)31,32,33part A; (4) Visual Processing speed and visual perception with the Salthouse Perceptual Comparison Test (SPCT)34,35and Symbol Digit Modalities Test (SDMT)33,36; (5) Visuospatial abilities with Visual Object and Space Perception Battery (VOSP)37cubes and dot counting, Grooved Pegboard test (GPT)38, and Benton Judgment of Line Orientation (BJLO)39,40; (6) Visual memory with the Taylor Complex Figure (TCF)41and the Brief Visuospatial Memory Test-Revised (BVMT-R)42,43; (7) Executive function with Modified Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (M-WCST)44,45and TMT part B; (8) Verbal fluency with the FAS Word Fluency and letter P46. Supplementary Table 1 presents the assessment protocol as well as the cognitive functions. However, it is important to note that, in neuropsychology, each test measures more than one cognitive domain simultaneously, which is a critical consideration. For this reason, we conducted a confirmatory factor analysis to ensure that the measures assessed the cognitive domains of interest.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were carried out using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 20.0 (IBM-SPSS, Armonk, New York) for all the analysis except for the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) for which the lavaan package (Rosseel, 2012) of the R statistical program (Core Team 2021) was used. The assumptions of normality and homogeneity of variances of the variables were analyzed. Descriptive analyses were performed for the mean and standard deviation of each variable. The scores of Trail Making test (TMT) part A and B, Grooved Pegboard Test time, Modified Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (M-WCST) perseverative and total errors were inverted. Cognitive composites were created by averaging z-scores of cognitive tests in each domain [visual attention: TMT-A (inverted), Stroop Word, Stroop Color and Stroop Word-Color; visual processing speed/visual perception: Salthouse Perceptual Comparison Test, Symbol Digit Modalities Test; Visuospatial abilities: Grooved Pegboard test, Visual perception with Visual Object and Space Perception Battery (VOSP cubes and dot-counting), Taylor Complex Figure-copy, Benton Judgment of Line Orientation; Visual Memory: Brief Visuospatial Memory Test-revised (BVMT-R total score and delayed recall), Taylor Complex Figure-memory; Executive Functions: Modified Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (M-WCST total categories, perseverative errors and total errors), TMT Part B; Verbal fluency: letters F, A, S, and P]. Confirmatory factor analysis was performed using the total sample to verify the construct validity of these 6 cognitive domains (visual attention, visual processing speed/visual perception, visuospatial abilities, visual memory, executive functions, and verbal fluency) (Fig. 1). The model presented adequate fit values: Comparative Fit Index (CFI) = 0.90, Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) = 0.88, and Root Mean Square.

Confirmatory factor analysis of cognitive domains. Note: Visual attention [TMT (Trail Making Test) part A, Stroop Word, Stroop Color, Stroop Word-Color]; Visual processing speed/visual perception [Salthouse Perceptual Comparison Test (SPCT), Symbol Digit Modalities Test (SDMT)]; Visuospatial abilities: [Grooved Pegboard test (GPT), Visual perception with Visual Object and Space Perception Battery (VOSP cubes and dot-counting), Taylor Complex Figure (TFC copy), Benton Judgment of Line Orientation (BJLO)]; Visual Memory: [Brief Visuospatial Memory Test-revised (BVMT-R total score and delayed recall), TFC memory]; Executive Functions: [Modified Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (M-WCST total categories, perseverative errors and total errors), TMT Part B]; Verbal fluency: letters F, A, S, and P.

One-way ANOVA and Tukey’s HSD Test for multiple comparisons were performed for the sociodemographic and clinical data to investigate the differences between groups. One-way ANCOVA, with age as covariate, was conducted for post hoc analysis for motor status and cognition to compare the differences between groups.

A stepwise linear regression (excluding the HC group) was carried out to analyze the percentage of variance explained by age, years of education, CAG repeats, motor status (measured with the UHDRS), executive functions, and verbal fluency across the following visual cognitive domains: visual attention, visual processing speed/visual perception, visuospatial abilities, visual memory. For the executive functions and verbal fluency, we also performed a stepwise linear regression including age, years of education, CAG repeats, and motor status as predictors.

The receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was used as a method to evaluate the ability of the cognitive measures to classify and discriminate between HC and manifest HD patients (including both early manifest and manifest groups), pre-manifest HD vs. manifest HD (early manifest and manifest groups), and HC and Pre-manifest HD.

Results

The general clinical characteristics of participants are presented in Table 1. The participants were predominantly female (56%). The mean age and education of the total sample were 49.8 ± 12.0 years and 12.7 ± 3.7 years, respectively. Statistically significant differences were found between groups in age (F = 4.9; p = .001), and the number of CAG repeats (F = 14.0; p < .001). The pre-manifest group was younger than the other groups and the manifest group who had the highest number of CAG repeats (44.1 ± 3.0). No differences were found between groups in education or in age at onset of first symptoms. As expected, the manifest HD group had higher motor impairment in the UHDRS (42.0 ± 21.7) compared to early manifest HD patients (25.0 ± 14.1, p < .001). We did not find statistical differences in general cognition (MoCA), neither in the different visual cognitive functions between HC, reduced penetrance and pre-manifest groups, except for visual memory that there were significant differences between reduced penetrance and pre-manifest (p = .003), and also marginal significant differences between HC and reduced penetrance (p = .074). Additionally, visual memory was the only cognitive domain that there were no significant differences between early manifest and manifest (Table 2; Fig. 2. See supplementary Table 2 for the raw data of the cognitive measures).

Cognitive differences between groups. *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p ≤ .001. Note: HC = Healthy Controls; RP = Reduced Penetrance group. The figure shows the boxplots from the ANCOVA and post hoc analysis performed between groups for each cognitive domain. General Cognition: MoCA total score; Visual attention: [TMT (Trail Making Test) part A, Stroop Word, Stroop Color, Stroop Word-Color]; Visual processing speed/visual perception [Salthouse Perceptual Comparison Test (SPCT), Symbol Digit Modalities Test (SDMT)]; Visuospatial abilities: [Grooved Pegboard test (GPT), Visual perception with Visual Object and Space Perception Battery (VOSP cubes and dot-counting), Taylor Complex Figure (TFC copy), Benton Judgment of Line Orientation (BJLO)]; Visual Memory: [Brief Visuospatial Memory Test-revised (BVMT-R total score and delayed recall), TFC memory]; Executive Functions: [Modified Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (M-WCST total categories, perseverative errors and total errors), TMT Part B]; Verbal fluency: letters F, A, S, and P.

Predicted factors in general and visual cognition across HD carriers

According to the stepwise linear regression, age, education, CAG repeats, motor status, executive function and verbal fluency explained between 1.3 and 72.8% of the variance in general cognition and visual cognitive functions (Table 3; Fig. 3) across the spectrum of HD groups. Executive function explained the highest percentage of variance in general cognition (56.8%), while motor status explained the highest in the rest of the cognitive domains, ranging from 37.2% in executive function to 72.8% in visuospatial abilities.

Predicted effects of age education, clinical data, executive function and verbal fluency in cognition. The figure illustrates the percentage of variance explained by age education and clinical data in each model. Note: Motor status was assessed with the Unified Huntington’s Disease Rating Scale (UHDRS): General cognition was assessed with the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA). Visual attention [TMT (Trail Making Test) part A, Stroop Word, Stroop Color, Stroop Word-Color]; Visual processing speed/visual perception [Salthouse Perceptual Comparison Test (SPCT), Symbol Digit Modalities Test (SDMT)]; Visuospatial abilities: [Grooved Pegboard test (GPT), Visual perception with Visual Object and Space Perception Battery (VOSP cubes and dot-counting), Taylor Complex Figure (TFC copy), Benton Judgment of Line Orientation (BJLO)]; Visual Memory: [Brief Visuospatial Memory Test-revised (BVMT-R total score and delayed recall), TFC memory]; Executive Functions: [Modified Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (M-WCST total categories, perseverative errors and total errors), TMT Part B]; Verbal fluency: letters F, A, S, and P.

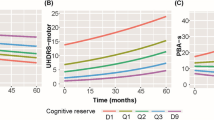

The results from the stepwise linear regression analysis by group (Fig. 4) showed differences between groups. In the pre-manifest group, executive function was the only variable explaining general cognition (31.2%) and visuospatial abilities (38.2%). Age, education, CAG repeats, motor status, executive function and verbal fluency explained between age (9.6%)- executive functions (38.2%) of the variance in the different visual cognitive functions. Visual processing speed was mostly explained by verbal fluency (30.3%) and age (25.1%), visual memory by age (24.6%) and CAG repeats (12.8%) in pre-manifest group, while verbal fluency was just explained by education (19.4%), and executive functions by education (22.3%) and motor status (20.1%). In the early manifest group, general cognition was mostly explained by executive functions (54.9%) but also by motor status (9.8%), while the visual cognitive functions were explained by verbal fluency (from 12.4 to 55.7%), motor status (from 14.1 to 52.5%), and executive functions (19.1%). Lastly, in the manifest group, verbal fluency explained the 52.4% of general cognition, and visual cognitive functions were also explained by verbal fluency (from 55.3 to 60.5%), motor status (from 5.5 to 66.9%), and age (from 8.4% to 19,2%).

Predicted effects of age, education, CAG repeats, motor status, executive functions and verbal fluency in cognition by groups. Pre-manifest patients. Early manifest HD patients. Manifest HD patients. The figure illustrates the percentage of variance explained by age education and clinical data in each model separately by pre-manifest HD, early manifest HD, and manifest HD group. Note: Motor status was assessed with the Unified Huntington’s Disease Rating Scale (UHDRS): General cognition was assessed with the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA). Visual attention [TMT (Trail Making Test) part A, Stroop Word, Stroop Color, Stroop Word-Color]; Visual processing speed/visual perception [Salthouse Perceptual Comparison Test (SPCT), Symbol Digit Modalities Test (SDMT)]; Visuospatial abilities: [Grooved Pegboard test (GPT), Visual perception with Visual Object and Space Perception Battery (VOSP cubes and dot-counting), Taylor Complex Figure (TFC copy), Benton Judgment of Line Orientation (BJLO)]; Visual Memory: [Brief Visuospatial Memory Test-revised (BVMT-R total score and delayed recall), TFC memory]; Executive Functions: [Modified Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (M-WCST total categories, perseverative errors and total errors), TMT Part B]; Verbal fluency: letters F, A, S, and P.

ROC curve analysis of cognitive domains between Huntington’s disease carriers and healthy controls

The ROC curve analyses revealed that all cognitive domains, particularly the visual domains, effectively discriminated between HC and manifest HD patients (including both early manifest and manifest groups), as well as between pre-manifest and manifest HD patients (early manifest and manifest groups) (Fig. 5). The areas under the curve (AUC) for these groups ranged from 0.72 for executive functions to 0.92 for visuospatial abilities in both comparisons. Among the visual domains, visuospatial abilities demonstrated the highest discriminative power between HC and manifest HD, as well as between pre-manifest and manifest HD, followed by visual memory, visual attention, and visual processing speed/visual perception. In contrast, the discrimination between HC and pre-manifest HD was lower, with AUC values ranging from 0.43 for executive functions to 0.57 for verbal fluency and visual memory, followed by visuospatial abilities and general cognition.

ROC Curve of cognitive domains between groups. Note: This image displays ROC curves (Receiver Operating Characteristic) from three comparisons related to Huntington’s Disease (HD) [Healthy controls vs. Manifest HD patients (early manifest and manifest group), Pre-manifest HD vs. Manifest HD (early manifest and manifest group), and Healthy controls vs. Pre-manifest HD] and different cognitive domains: General cognition measured by MoCA total, Visual attention [TMT (Trail Making Test) part A, Stroop Word, Stroop Color, Stroop Word-Color]; Visual processing speed/visual perception [Salthouse Perceptual Comparison Test (SPCT), Symbol Digit Modalities Test (SDMT)]; Visuospatial abilities: [Grooved Pegboard test (GPT), Visual perception with Visual Object and Space Perception Battery (VOSP cubes and dot-counting), Taylor Complex Figure (TFC copy), Benton Judgment of Line Orientation (BJLO)]; Visual Memory: [Brief Visuospatial Memory Test-revised (BVMT-R total score and delayed recall), TFC memory]; Executive Functions: [Modified Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (M-WCST total categories, perseverative errors and total errors), TMT Part B]; Verbal fluency: letters F, A, S, and P.

Discussion

This study aimed to investigate the early presence of visual cognitive deficits in HD carriers, including pre-manifest, early manifest and manifest HD patients, and also participants with reduced penetrance by evaluating differences in their cognitive and visual performance, compared to HC. Our study revealed no significant differences in general cognition, among pre-manifest, reduced penetrance, and HC groups, suggesting that general cognitive function remains relatively intact until later stages of HD. However, the results highlighted significant differences in visual memory between pre-manifest and reduced penetrance groups, showing the pre-manifest group a lower visual memory performance than the reduced penetrance group. While no differences were shown between early manifest and manifest HD patients in this visual domain, suggesting that visual memory was already impaired. Therefore, visual memory may serve as an early indicator of cognitive decline in HD, warranting further exploration into the specific visual cognitive domains affected in the pre-manifest stage. According to previous studies, pre-manifest patients showed lower cognitive performance in verbal fluency, executive function, and memory, including short-term and delayed recall, visuospatial abilities, visual processing speed47,48,49,50. However, none of these studies focused specifically on visual cognition or visual cognitive functions.

As expected, the manifest HD group displayed higher motor, general and visual cognitive impairment compared to early manifest patients, which aligns with the established clinical understanding of the progression of HD2,51. However, no such differences were noted in visual memory or verbal fluency between these two manifest groups. This finding is noteworthy, as it suggests that certain cognitive domains may decline in a more uniform manner across different stages of the disease. The absence of significant differences in visual memory between these two manifest groups indicates that visual memory deficits may emerge early in the disease course and remain relatively stable as the disease progresses. Similarly, the lack of distinction in verbal fluency suggests that language-related cognitive abilities may follow a similar progression, potentially connecting to motor speech issues such as anarthria and dysarthria52,53. While verbal fluency is traditionally considered a test of language ability, its performance is also influenced by executive functions. Given the cognitive symptoms associated with HD, it is reasonable to assume that executive functions and psychomotor speed may significantly affect the performance of other cognitive domains. This raises important questions regarding the nature of cognitive decline in HD and suggests that interventions aimed at supporting these specific cognitive areas might be necessary throughout the disease course.

The findings highlighted the multifaceted nature of cognitive impairment in HD and the significant predictors in general cognition and visual cognitive functions among HD carriers. A range of factors—including age, education, CAG repeats, motor status, executive function, and verbal fluency—contributed to the visual cognitive profiles across the spectrum of HD. Notably, motor status had the highest predictive power in visual cognitive functions, verbal fluency and executive functions. This is particularly intriguing as it emphasizes the interconnectedness of motor and visual cognitive impairments in HD. The motor aspect includes an oculomotor component, marked by reduced gaze fixation and diminished visual analysis capacity. In addition, the high percentage of variance explained by motor status in visuospatial abilities may also reflect the underlying neurobiological mechanisms linking motor control and visual perception. As motor function declines, so too may the ability to process and interact with visual stimuli, leading to significant challenges in daily activities that require visuospatial awareness, such as navigating environments or recognizing objects17,54. On the other hand, executive function emerged as the strongest predictor in general cognition, aligning with existing literature that highlights executive dysfunction as a hallmark of cognitive decline in HD16,18, impacting a range of abilities essential for daily functioning, including planning, problem-solving, and cognitive flexibility. Age and CAG repeats are well-established predictors of disease onset and progression55, and the influence of education and verbal fluency on cognition underscores the potential for modifiable factors to impact cognitive outcomes56. For instance, higher levels of education may provide cognitive reserve, potentially mitigating some effects of neurodegeneration. Understanding these relationships could inform targeted interventions that address specific cognitive deficits while considering individual patient profiles.

On the other hand, the findings among the different HD groups differed from the total HD carrier’s sample. In the pre-manifest group, executive function emerged as the sole significant predictor of both general cognition and visuospatial abilities, suggesting that even before the onset of motor symptoms, executive function may serve as a critical marker of cognitive decline in HD carriers, especially in visuospatial abilities. Notably, visual processing speed was primarily accounted for by verbal fluency and age, while visual memory was influenced also by age and CAG repeats57. This suggests that while executive function is paramount in the pre-manifest stage, other factors, particularly age and CAG repeats, also play essential roles in shaping cognitive outcomes51,56.

In the early manifest group, executive functions remained the primary predictor of general cognition, highlighting the progressive nature of cognitive impairment associated HD. Additionally, motor status began to contribute to general cognition, showing a possible link between physical symptoms and cognitive performance. The predictors for visual cognitive functions in the early manifest group broadened to include verbal fluency and motor status, reflecting a more complex interplay of factors influencing cognitive outcomes at this stage. The inclusion of verbal fluency as a significant predictor indicated that language skills may also begin to decline as HD progresses and therefore, motor aspects of language, contributing to overall cognitive impairment58,59. Deficits in verbal fluency could serve as an early indicator of broader cognitive decline and may warrant further assessment in clinical settings.

Finally, in the manifest group, verbal fluency emerged as the most substantial predictor in general and visual cognitive functions. This shift underscores the increasing prominence of language and verbal skills in the later stages of HD59, potentially reflecting the broader cognitive decline experienced by patients as they navigate more complex cognitive demands. Motor status also showed a wide range of influence on visual cognitive functions, especially in visuospatial abilities, indicating a relationship between the impairment of motor symptoms and the decline in visual cognitive abilities. Age remained also a relevant factor, further emphasizing the ongoing impact of aging in conjunction with the progression of HD. These findings illustrated the dynamic nature of cognitive impairment in HD, with different predictors gaining or losing importance as the disease advances. The emphasis on executive functions in the early stages shifted toward a more multifaceted model in the later stages, where verbal fluency and motor status also significantly influence cognitive outcomes. This progression suggests that targeted interventions addressing executive dysfunction in the pre-manifest and early manifest stages may be beneficial, while interventions in the manifest stage could focus more on enhancing verbal fluency and managing motor symptoms.

Cognition and specifically visual cognitive domains emerged as particularly effective in discriminating between manifest HD patients—encompassing both early manifest and manifest groups—and HC22,24,60. Visuospatial abilities were the most discriminative domain between groups, followed by visual memory and visual attention. Our findings suggest that visual cognitive impairments, particularly visuospatial abilities rather than executive functions as might be expected, were prominent features in the manifestation of HD. The fact that visuospatial abilities were the most distinguishing domain between HC and manifest HD, as well as between premanifest HD and manifest HD, rather than executive function, is a significant finding, especially since the measures used to assess executive function also included aspects of visual abilities. This supports the idea that visual cognition and visual cognitive functions are closely linked to the disease’s progression and could serve as a key indicator of cognitive decline in HD.

Furthermore, the ability of visual memory and visual attention to discriminate between these groups emphasizes the importance of assessing a broad range of cognitive functions, as deficits in these areas can significantly impact daily functioning and quality of life for HD patients. Conversely, lower discrimination power was found when comparing HC to pre-manifest HD individuals, indicating that cognitive measures alone may be less effective in identifying subtle changes in cognition among pre-manifest HD carriers, which may reflect the relatively preserved cognitive functions at this stage. It also highlighted the potential challenges in diagnosing pre-manifest HD, as cognitive impairments may not yet be pronounced enough to differentiate these individuals from HC. This finding is critical for clinical practice, as it underscores the need for more sensitive measures or composite assessments that could capture early cognitive changes in asymptomatic HD individuals.

Our study has some limitations. Firstly, although we started with a large sample of HD carriers -a rare genetic condition- the sample size was considerably reduced once divided into groups, particularly in the reduced penetrance group. Therefore, conclusions drawn for this group should be interpreted with caution due to the small sample size. Secondly, as this is a cross-sectional study, future research should include longitudinal studies to analyze the progression of symptoms, overall cognitive impairment, and visual cognitive performance in HD carriers, while also aiming to increase the sample size of the reduced penetrance group. Thirdly, in neuropsychology, tests often evaluate multiple cognitive domains simultaneously, which must be considered. To address this, we conducted a confirmatory factor analysis to validate that the measures accurately reflected the cognitive domains of interest. For example, the Stroop test is commonly used to evaluate resistance to interference, which is part of executive functions. However, we decided not to include the specific measure of interference resistance and instead focused on visual attention. Fourthly, we did not find differences in general cognition, as measured by the MoCA, between the reduced penetrance, premanifest, and HC groups. This could suggest that the MoCA may not be sensitive enough to detect differences between these groups. Therefore, future studies could consider using other screening tests or assessing general cognition with separate, more detailed measures. Lastly, highlight that most of our patients had no disease awareness, and as this study pointed out, before the motor symptoms appear there are non-motor symptoms, such as cognitive impairment with special affection of visual cognitive domains, especially visual memory, that are early impaired. Our study emphasizes that the sooner symptoms are identified, especially non-motor symptoms, the sooner the patient can be treated.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this study underscores the importance of early assessment of visual cognitive functions, particularly visual memory, in HD carriers. Visual memory deficits may serve as an early marker of cognitive decline in HD. Additionally, visual cognitive domains—primarily visuospatial abilities, followed by visual memory and visual attention—were more effective in distinguishing early and manifest HD patients from HC, as well as differentiating pre-manifest from early and manifest HD, compared to executive functions. This supports the notion that visual cognitive domains are closely linked to HD progression. Understanding the visual cognitive profiles can facilitate earlier interventions and enhance genetic counseling for at-risk individuals, ultimately improving quality of life and providing insight into potential therapeutic options.

Data availability

Data is available upon reasonable request. Rocio Del Pino (delpinorocio@gmail.com) could be contacted if someone wants to request the data from this study.

Change history

26 December 2025

The original online version of this Article was revised: In the original version of this Article, the Author names Rocío del Pino, Amaia Ortiz de Echevarría and Juan Carlos Gómez Esteban were incorrectly indexed. The original Article has been corrected.

References

Ellis, N. et al. Genetic risk underlying Psychiatric and cognitive symptoms in Huntington’s Disease. Biol. Psychiatry. 87, 857–865 (2020).

McAllister, B. et al. Timing and impact of Psychiatric, Cognitive, and Motor Abnormalities in Huntington Disease. Neurology 96, E2395–E2406 (2021).

Kumar, A. et al. Therapeutic advances for huntington’s disease. Brain Sciences vol. 10 Preprint at (2020). https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci10010043

Purdon, S. E., Mohr, E., Ilivitsky, V. & Jones, B. D. W. Huntington’s Disease: Pathogenesis, Diagnosis and Treatment.

McNeil, S. M. et al. Reduced penetrance of the Huntington’s disease mutation. Hum. Mol. Genet. 6, (1997).

Rubinsztein, D. C. et al. Phenotypic characterization of individuals with 30–40 CAG repeats in the Huntington disease (HD) gene reveals HD cases with 36 repeats and apparently normal elderly individuals with 36–39 repeats. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 59, (1996).

Quarrell, O. W. J. et al. Reduced penetrance alleles for Huntington’s disease: a multi-centre direct observational study. Journal of medical genetics vol. 44 Preprint at (2007). https://doi.org/10.1136/jmg.2006.045120

Penney, J., Vonsatte, J. P., Macdonald, M., Gusella, J. & Myers, R. CAG repeat number governs the development rate of pathology in Huntington’s disease. Ann. Neurol. (2004).

Wang, R. et al. Metabolic and hormonal signatures in pre-manifest and manifest Huntington’s disease patients. Front Physiol 5 JUN, (2014).

Zhang, L. et al. Therapeutic reversal of Huntington’s disease by in vivo self-assembled siRNAs. Brain vol. 144 3286–3287 Preprint at (2021). https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awab398

Martí-Martínez, S. & Valor, L. M. A Glimpse of Molecular Biomarkers in Huntington’s Disease. International Journal of Molecular Sciences vol. 23 Preprint at (2022). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23105411

Paulsen, J. S. Cognitive impairment in Huntington disease: diagnosis and treatment. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 11, (2011).

Murueta-Goyena, A. et al. Retinal thickness as a biomarker of cognitive impairment in manifest Huntington’s disease. J. Neurol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-023-11720-3 (2023).

Kersten, H. M., Danesh-Meyer, H. V., Kilfoyle, D. H. & Roxburgh, R. H. Optical coherence tomography findings in Huntington’s disease: a potential biomarker of disease progression. J. Neurol. 262, (2015).

Gulmez Sevim, D., Unlu, M., Gultekin, M. & Karaca, C. Retinal single-layer analysis with optical coherence tomography shows inner retinal layer thinning in Huntington’s disease as a potential biomarker. Int. Ophthalmol. 39, (2019).

Fernández-Valle, T. & M.-G. A. Huntington’s Disease, Cognition, and biological markers. in Handb. Behav. Psychol. Disease 1–26 (2024).

Zhang, S., Shen, L. & Jiao, B. Cognitive Dysfunction in Repeat Expansion Diseases: A Review. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience vol. 14 Preprint at (2022). https://doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2022.841711

Pfalzer, A. C. et al. Impairments to executive function in emerging adults with Huntington disease. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 94, (2022).

Fernández-Valle, T. & Murueta-Goyena, A. Huntington’s Disease, Cognition, and biological markers. in Handbook of the Behavior and Psychology of Disease 1–26 (Springer International Publishing, Cham, doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-32046-0_56-1. (2024).

Killoran, A. The Clinical Features of Huntington’s Disease. (2017).

Cavanagh, P. Visual cognition. Vision Research Preprint at (2011). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.visres.2011.01.015

Coppen, E. M., van der Grond, J., Hart, E. P., Lakke, E. A. J. F. & Roos, R. A. C. The visual cortex and visual cognition in Huntington’s disease: An overview of current literature. Behavioural Brain Research vol. 351 63–74 Preprint at (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbr.2018.05.019

Murueta-Goyena, A. et al. Retinal thickness as a biomarker of cognitive impairment in manifest Huntington’s disease. J. Neurol. 270, (2023).

Dhalla, A., Pallikadavath, S. & Hutchinson, C. V. Visual Dysfunction in Huntington’s Disease: A Systematic Review. Journal of Huntington’s Disease vol. 8 Preprint at (2019). https://doi.org/10.3233/JHD-180340

Coppen, E. M., van der Grond, J., Hafkemeijer, A., Barkey Wolf, J. J. H. & Roos, R. A. C. Structural and functional changes of the visual cortex in early Huntington’s disease. Hum. Brain Mapp. 39, (2018).

McDonnell, E. I., Wang, Y., Goldman, J. & Marder, K. Age of Onset of Huntington’s disease in carriers of reduced penetrance alleles. Mov. Disord. 36, (2021).

Kieburtz, K. Unified Huntington’s disease rating scale: reliability and consistency. Mov. Disord. 11, (1996).

Nasreddine, Z. S. et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 53, (2005).

Ojeda, N., del Pino, R., Ibarretxe-Bilbao, N., Schretlen, D. J. & Peña, J. Montreal cognitive assessment test: normalization and standardization for Spanish population. Rev. Neurol. 63, (2016).

Golden, C. J. Stroop: Test De Colores Y Palabras (TEA Ediciones, 2001).

Reitan, R. M. & W. D. The Halstead-Reitan Neuropsychological Test Battery: Theory and Clinical Interpretation. vol. 4Neuropsychology press., (1985).

Sáez-Atxukarro, O., Peña, J., del Pino, R., Ibarretxe-Bilbao, N. & Ojeda, N. Reliable change indices for 16 neuropsychological tests at six different time points. Neurología 1-23 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nrl.2023.06.004 (2024).

Peña-Casanova, J. et al. Spanish multicenter normative studies (NEURONORMA project): norms for verbal span, visuospatial span, letter and number sequencing, trail making test, and symbol digit modalities test. Arch. Clin. Neuropsychol. 24, (2009).

Peña, J., del Pino, R., Ibarretxe-Bilbao, N., Schretlen, D. J. & Ojeda, N. The salthouse perceptual comparison test: normalization and standardization for Spanish population. Rev. Neurol. 62, (2016).

Salthouse, T. A. Mediation of adult age differences in cognition by reductions in working memory and speed of processing. Psychol. Sci. 2, 179–183 (1991).

Smith, A. Symbol Digits modalities Test Manual (10 th printing). Western Psychol. Serv. Los Angeles (2007).

Warrington, E. K. & James, M. The visual object and space perception battery. (1991).

Matthews, C. And K. H. Neuropsychological Test Battery ManualWI (University of Wisconsin Neuropsychology Laboratory, 1964).

Benton, A. L. et al. Contributions to Neuropsychological Assessment A Clinical Manual (Oxford University Press, 1994).

Benton, A. L. N. R. V. and K. deS Hamsher. Judgment of line orientation. (1983).

del Pino, R., Peña, J., Ibarretxe-Bilbao, N., Schretlen, D. J. & Ojeda, N. Taylor complex figure test: administration and correction according to a normalization and standardization process in Spanish population. Rev. Neurol. 61, (2015).

Benedict, R. H. B., Groninger, L., Schretlen, D., Dobraski, M. & Shpritz, B. Revision of the brief visuospatial memory test: studies of normal performance, reliability, and, validity. Psychol. Assess. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.8.2.145 (1996).

Sáez Atxukarro, O. et al. Test breve de memoria visuoespacial-revisado: normalización y estandarización de la prueba en población española. Rev. Neurol. 72, (2021).

del Pino, R., Peña, J., Ibarretxe-Bilbao, N., Schretlen, D. J. & Ojeda, N. Modified Wisconsin card sorting test: standardization and norms of the test for a population sample in Spain. Rev. Neurol. 62, (2016).

Schretlen, D. J. Modified Wisconsin Card Sorting Test®: M-WCSTProfessional Manual. PAR.,. (2010).

Spreen, O. & B. A. L. Neurosensory Center Comprehensiveexamination for Aphasia: Manual of Instructions (NECCEA).Victoria, (1969).

Verny, C. et al. Cognitive changes in asymptomatic carriers of the Huntington disease mutation gene. Eur. J. Neurol. 14, 1344–1350 (2007).

Duff, K., Beglinger, L. J., Theriault, D., Allison, J. & Paulsen, J. S. Cognitive deficits in Huntington’s disease on the repeatable battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status. J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsychol. 32, 231–238 (2010).

Wahlin, T. B. R., Lundin, A. & Dear, K. Early cognitive deficits in Swedish gene carriers of Huntington’s disease. Neuropsychology 21, 31–44 (2007).

del Barrio, T. et al. Visual Processing disorders in patients with Huntington’s Disease and Asymptomatic Carriers. J. Neurol. vol. 243 (1996).

Julayanont, P., McFarland, N. R. & Heilman, K. M. Mild cognitive impairment and dementia in motor manifest Huntington’s disease: classification and prevalence. J. Neurol. Sci. 408, (2020).

Diehl, S. K. et al. Motor speech patterns in Huntington disease. Neurology 93, (2019).

Hartelius, L., Carlstedt, A., Ytterberg, M., Lillvik, M. & Laakso, K. Speech disorders in mild and moderate Huntington disease: results of dysarthria assessments of 19 individuals. J. Med. Speech Lang. Pathol. 11, (2003).

Mohr, E., Claus, J. J. & Brouwers, P. Basal ganglia disease and visuospatial cognition: are there disease-specific impairments? Behav. Neurol. 10, (1997).

Hahn-Barma, V. et al. Are cognitive changes the first symptoms of Huntington’s disease? A study of gene carriers. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 64, (1998).

Verny, C. et al. Cognitive changes in asymptomatic carriers of the Huntington disease mutation gene. Eur. J. Neurol. 14, (2007).

Swami, M. et al. Somatic expansion of the Huntington’s disease CAG repeat in the brain is associated with an earlier age of disease onset. Hum. Mol. Genet. 18, (2009).

Wahlin, T. B. R., Luszcz, M. A., Wahlin, Å. & Byrne, G. J. Non-verbal and verbal fluency in Prodromal Huntington’s Disease. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Dis. Extra 5, (2015).

de Lucia, N. et al. Perseverative behavior on verbal fluency task in patients with Huntington’s disease: a retrospective study on a large patient sample. Arch. Clin. Neuropsychol. 35, (2021).

Wolf, R. C. et al. Visual system integrity and cognition in early Huntington’s disease. Eur. J. Neurosci. 40, (2014).

Acknowledgements

We want to thank all participants for their involvement in this project. Special thanks to all the clinicians who participated in this project from all the hospitals involved but specially to the Cruces University Hospital and all the members of the Neurodegenerative Diseases group at Biobizkaia Health Research Institute. Thanks to Silvia Perez Fernandez, biostatistician at Biobizkaia Health Research Institute, to Ángela Saenz and Unai Ayala for their support in the study.

Funding

This research has been partially funded by the EITB Maratoia call for Rare Diseases (BIO17/ND/009) and by the Health Department of the Basque Government (2019111004).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RDP contributed to the conception, design, and coordination of the study and interpretation of the results. RDP contributed to the acquisition and analysis of data and the initial and final manuscript. RDP and MAG performed the recruitment and evaluations of the patients. RDP and JCGE supervised the project. All authors contributed to the critical revision of the manuscript and final version approval.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics declarations

The study protocol was approved by the regional Basque Clinical Research Ethics Committee (PI2020117). All participants gave written informed consent prior to their participation in the study, in accordance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Del Pino, R., Acera, M.Á., Ortiz de Echevarría, A. et al. Characterization of visual cognition in pre-manifest, manifest and reduced penetrance Huntington’s disease. Sci Rep 15, 4707 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88406-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88406-5