Abstract

Limited data are available on the causes of hydrops fetalis in dogs. Congenital heart defects may be an important contributing factor. Standard autopsy often fails to provide a comprehensive and accurate diagnosis on very small hearts. This study was carried out on five French bulldog puppies all presenting with advanced hydrops fetalis and four diagnosed with pulmonary hypoplasia at autopsy. The body weight of the dogs ranged from 142 to 687 g and the heart with lungs weighed from 4.5 to 23.6 g. The hearts and pulmonary vessels were filled with barium contrast, and micro-CT scans of the physiologically connected heart and lungs were performed. In all five puppies, we confirmed congenital heart defects including: Puppy #1. Perimembranous ventricular septal defect and aortic dextroposition; Puppy #2. Interrupted aortic arch with aortic valve dysplasia and aortic stenosis; Puppy #3. Tricuspid valve dysplasia and bicuspid pulmonary trunk valve; Puppy #4. Aortic stenosis and ventricular septal defect; Puppy #5. Tricuspid valve dysplasia. Additionally, four puppies had pulmonary vascular hypoplasia. Contrast-enhanced micro-CT can provide highly accurate diagnosis of complex congenital heart and lung defects. Examination of the heart in conjunction with the lungs appears to be a rational approach in animals with hydrops fetalis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Congenital heart defects (CHDs) are one of the most common congenital defects in humans1. Their estimated incidence varies depending on the target population (fetuses from spontaneous or induced abortions or children examined after birth) and diagnostic methods used (ante- vs. postmortem). The proportion of liveborn infants with any CHD is estimated at 1.2% and with severe CHD at 0.3% 2. In the study including almost 780,000 fetal ultrasounds, severe CHDs were detected in 0.4% fetuses3. In the anatomical studies, the CHD was present in as many as 23% of aborted fetuses4. Moreover, the occurrence of CHDs in the first half of pregnancy is estimated to be much higher than after the 22nd week of pregnancy5. Studies on the CHD occurrence in animals are based on their detection in the postnatal echocardiographic examination6,7,8. Obviously, these studies describe only non-lethal CHDs. As a consequence, data on the incidence of severe, lethal birth defects, including CHDs, in animals are scarce. One of the most common congenital syndromes in dogs is hydrops fetalis (congenital edema, fetal anasarca, HF)9,10. The term refers to an excessive accumulation of fetal fluid in body cavities (peritoneal or pleural cavity or pericardial sac) and in the subcutaneous tissue. Based mostly on analogy with human medicine and occasional case reports11, HF is suspected to be the manifestation of CHDs in dogs12, however scientific confirmation of this suspicion is lacking, mainly due to shortage of diagnostic methods sufficiently precise to be used in newborn dogs whose body and organ size are usually much smaller than in humans.

For many years, an autopsy had been considered the gold standard for post-mortem diagnosis of CHD. Initial attempts at post-mortem cardiac imaging showed low diagnostic accuracy caused by the 2-dimensional (2-D) imaging, low-resolution (2–5 mm slice thickness), lack of tissue contrast, and limited knowledge and experience of general radiologists in CHD diagnostics. In early studies, post-mortem cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) managed to detect from 53%13 to even 0%14 of CHDs evident in the autopsy. Along with the development of imaging and contrasting techniques, the post-mortem contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) angiography has become a new gold standard for visualizing cardiac structures in adult people15. Further progress in imaging diagnostics led to the development of the computed microtomography (micro-CT) which allows for imaging small objects with a resolution of several micrometers. Studies have shown that the micro-CT allows for examination of hearts of small size and low weight in which the conventional autopsy tends to overlook important anomalies16,17,18. The micro-CT also enables tracing coronary vessels and visualizing lungs after intravenous contrast and cast medium injection (contrast-enhanced micro-CT)19,20. This opens completely new opportunities for investigating CHDs in veterinary medicine. Therefore, taking advantage of broader availability of contrast-enhanced micro-CT, we decided to investigate the etiology of HF in dogs.

Results

The body weight of the dogs ranged from 142 g to 687 g and the heart with lungs weighed from 4.5 g to 23.6 g. Two dogs had cleft palate (#1 and #2) and two dogs had renomegaly (#1 and #5), accompanied by hepatomegaly in one of them (#1).

In all dogs, hemorrhagic fluid was present in the body cavities – 3 dogs (#1, #4, #5) had hydropericardium, hydrothorax, and ascites, one dog (#2) had hydrothorax and ascites, and one dog (#3) had sole hydrothorax. All dogs had swelling of the subcutaneous tissue (anasarca). A wide PDA was apparent in all puppies, in dog #5 its diameter equaled the diameter of the pulmonary trunk.

The most prominent defect visible in the micro-CT and autopsy in 4/5 dogs (#1, #3, #4 and #5) was pulmonary artery hypoplasia with resultant hypoplasia of the lungs, especially severe in dog #1 (Figs. 1, 2 and 3). Three of these dogs (#1, #4, #5) had enlargement of the right atrium. The right ventricle was also enlarged, along with the left atrium and the right ventricle in dog #2 in which the interrupted aortic arch was present (Fig. 4). Another common defect, present in 4/5 dogs was the valvular dysplasia affecting various valves – aortic (dog #2 and #4), tricuspid (dog #5), and both tricuspid and pulmonic (dog #3) (Fig. 5). Two dogs (#1 and #4) had ventricular septal defect (VSD) (Fig. 6). Detailed results of all examinations are listed in Table 1.

Puppy #5. Cross-sectional view through the large artery at the level of the pulmonary trunk division. The ascending aorta, the pulmonary trunk, the hypoplastic right pulmonary artery, a small fragment of the atrium, and the short, initial segment of the hypoplastic departure of the left pulmonary artery are visible. LA left atrium, PT pulmonary trunk, RPA right pulmonary artery, LPA left pulmonary artery, AAo ascending aorta.

Puppy #1. Figure enables visualization of a defect in the interventricular septum and the displacement of the aorta over the right ventricle. RVI right ventricular inflow, RA right atrium, TV tricuspid valve, VSD ventricular septal defect, RVOT right ventricular outflow tract, Ao aorta. *Conal Septum (SC).

All specimens showed very good internal contrast on the barium-enhanced micro-CT scan. The combination of visual examination of the heart before contrast administration, the contrast-enhanced micro-CT and the conventional gross examination allowed to reach the definitive diagnosis.

Discussion

Many severe and complex CHDs are associated with poor prognosis and high mortality, especially in the absence of surgical management. In humans, it is estimated that CHDs are the cause of HF in 10% of cases23. However, some CHDs may remain undiagnosed due to small size of the heart and the fact that a conventional autopsy is performed by an anatomopathology specialist, but not by a specialist in the field of CHDs. In life-born infants with HF, 15,2% of cases appear to be caused by CHD24. In our study, all 5 puppies with HF had CHDs and 4 of them had concurrent pulmonary artery hypoplasia. Micro-CT is a relatively new method used for post-mortem examination of small size heart for diagnosis of CHD. Importantly, it is a non-destructive procedure that does not adversely affect the results of an autopsy25. Thus far, only a few studies employing this diagnostic method have been published, but all of them confirm the high usefulness of this method both in fetuses from the 8th week of pregnancy and children26,27. Micro-CT with contrast enables detailed visualization of both 2D and 3D cardiac morphology, without destroying the heart (contrary to conventional anatomopathological examination) and therefore allowing for multiple reviewing of the scans by various specialists. Conventional autopsy has long constituted a gold standard for diagnosing CHDs. However, recent advancements have shown that post-mortem micro-CT can reveal morphological details that conventional autopsy may miss due to their small size. According to Hutchinson et al.17, the cardiac micro-CT for detection of CHDs should be reviewed and interpreted by a specialist in pediatric cardiology. Some guidelines recommend an interdisciplinary team comprising a radiologist, a pathologist, and a cardiologist specializing in CHDs28,29. Our team included anatomists, cardiologists (both from medicine and veterinary), as well as a pediatric cardiac surgeon and a cardiologist specializing in imaging diagnostics (echocardiography, MRI, and CT) of CHDs in children. Micro-CT and conventional autopsy should be considered as complementary diagnostic approaches. The post-mortem micro-CT can provide invaluable guides for a pathologist performing an autopsy later on18. Recent publications indicate that micro-CT seems to be even more effective than conventional autopsy28 and may become an important alternative to autopsy25. In some medical facilities, computed micro-CT with iodine contrast has become the gold standard for post-mortem examination of healthy and diseased hearts30. The literature data shows that the most commonly used contrast agent is iodine, introduced into the tissues by immersing them in a solution containing iodine for a certain period of time17. In the iodine-contrast study, whole fetuses were placed in an iodine solution for 48–100 h. In our study, the cardiac filling procedure required 2 people and took an average of 1 h to complete, which markedly shortened the preparation time. According to the literature, iodine contrast does not affect the tissues and does not change the anatomical structure, but only slightly reduces the mass of tissues25. Unfortunately, such tests are performed on formalin-fixed tissues. Fixing with formalin causes hardening of tissues and their increased stiffness which has a negative effect on proper anatomopathological examination31,32,33. In all so far published studies on micro-CT, the hearts were examined separately from the lungs. To capture the potential relationship between heart and lung malformations, we decided to use a previously undescribed technique of simultaneous examination of naturally connected heart and lungs. The heart and lungs weight ranged from 2.4 to 23.6 g. Our previous unpublished experiences from examining such small formalin-fixed hearts confirm observations made in several published articles31,32,33 that stiffness and fragility of the tissues precluded reaching an accurate diagnosis in anatomopathological examination. Therefore, we decided to use a barium contrast which is suitable for unfixed tissues. We were able to make a full diagnosis in all micro-CT examinations. In all 5 puppies the micro-CT diagnosis was confirmed by conventional autopsy and we believe that these tests should be treated as complementary. During the anatomopathological examination we frequently referred back to the images obtained from the micro-CT.

All 5 puppies were diagnosed with CHDs. In 4 of them pulmonary arteries hypoplasia and lung hypoplasia were also confirmed. The abnormal development of the pulmonary vascularization and the resultant abnormal development of the lung tissue is secondary to the impaired blood supply due to CHDs34,35. Our study shows that micro-CT with barium contrast of small heart and lungs obtained from puppies with the average fetal weight of 380 g can provide accurate visualization of severe CHDs or lung vascularization defect. In addition, the use of barium contrast together with immobilization of tissues in agar solution during micro-CT allows for full anatomopathological examination of a fresh heart tissue. Micro-CT is also recognized in the diagnosis of heart defects in animals as small as rats both in fetuses and neonates16. One case has so far been described in the companion animals in which a 6 month-old cat with CHD was diagnosed using the micro-CT30. It is well known that animal models are of crucial importance for preclinical studies of the cardiovascular system28. Their use in animals may also be potentially useful for biomedical research since the number of available hearts with defects in humans is gradually decreasing along with dynamically developing prenatal and neonatal cardiac diagnostics and surgery. Classical education in the field of CHDs is based on the examination of collections of hearts with defects stored in formalin. Large archives become less accessible due to an effective enforcement of personal data protection, fewer anatomopathological examinations performed, wearing of existing collections over time, as well as the availability of cardiac surgery and increased patient survival36. Available collections such as in the laboratory of the Department of Descriptive and Clinical Anatomy, Medical University of Warsaw, date back to pre-operational times. The animal models, as in the case of our work, can be used for didactic and scientific purposes in the future. The general anatomy in animals is similar to human anatomy, and the practical applications of murine models of cardiovascular disease are generally accepted or even encouraged in medicine37,38. Micro-CT may also be used in the future to prepare virtual models or models in the 3D print for surgical training to aid understanding the complex morphology of CHDs.

Limitations

Potential tissue deformation caused by compression during the positioning of the heart itself and also air bubbles in contrast medium can be observed. Sequential image assessment is much easier than evaluating individual images and their spatial arrangement – not all images are displayed in standard cutting planes and spatial orientations when the heart is still situated within the patient’s body.

Potential tissue deformation caused by compression during the positioning of the heart itself and also air bubbles in contrast medium can be observed. Sequential image assessment is much easier than evaluating individual images and their spatial arrangement – not all images are displayed in standard cutting planes and spatial orientations when the heart is still situated within the patient’s body.

An additional limitation of this study is that it was conducted on puppies of a single breed—French Bulldogs—which may restrict the generalizability of the findings to other breeds. Future studies should include puppies from various breeds to determine whether the observed cardiac changes are consistent across different genetic backgrounds and to provide a more comprehensive understanding of hydrops fetalis.

Conclusion

Micro-CT with barium sulfate enables the post-mortem diagnosis of significant cardiovascular and pulmonary blood vessels abnormalities in puppies with HF. In our study, we detected high coincidence of complex CHDs with lungs hypoplasia so it seems reasonable to assess heart in conjunction with lungs. The interdisciplinary collaboration among cardiologists, pathologists specialized in CHDs, and cardiac surgeons is of paramount importance to establish an accurate diagnosis.

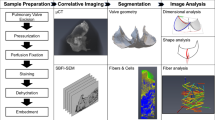

Methods

Animals

Five unrelated French Bulldog puppies, 4 females and 1 male, were obtained by caesarean sections performed on the due date at the veterinary clinic. All dogs died within a few minutes after birth with clinical signs of severe HF and were stored at -20 °C for further examination. To the best of our knowledge, supported by literature, freezing can induce histological artifacts in tissues, such as alterations in cellular and nuclear areas, but does not significantly alter the anatomical structure of the heart39,40. The freezing duration time ranged from a few days to approximately three months. HF was defined as fluid accumulation in at least 1 body cavity of the fetus (peritoneal, pleural or pericardial) accompanied by generalized subcutaneous edema. After thawing, a general conventional autopsy was performed. In four puppies lung hypoplasia was observed (Fig. 7). Heart and lungs were separated from the corpse in one piece.

Contrast technique administration

Previously described techniques of preparation and administration of the contrast and the mixture immobilizing the heart during the micro-CT examination11,21 were used with some modifications. First, the cranial and caudal vena cava were ligated. In 3 puppies, a Foley catheter (8Fr/Ch, ZARYS International Group, Poland) was placed in the descending aorta and the balloon was inflated with water so that the catheter tightly filled the lumen of the artery. In 1 of these 3 puppies, the Foley catheter itself tightly filled the aortic lumen and inflating the balloon was not needed. In 2 other puppies, the diameter of the aorta was too small to insert a Foley catheter and an intravenous catheter of 1.3 mm diameter (Becton Dickinson, USA) sealed with a clamped paean was used. The contrast was administered through the aorta, but in some cases, the entire heart could not be filled properly in this manner. In these cases, the catheter was withdrawn slightly and inserted through the aorta and the patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) towards the right ventricle so that the right part of the heart could be reached by the contrast. The contrast medium consisted of a mixture of 8 g of pork gelatin dissolved in 50 ml of hot water (temperature 95ºC) and 25 ml of barium sulfate (Barium sulfuricum Medana 1 g/ml, Polpharma, Poland). After removal of the catheter, the aorta was ligated. Then, the heart and lungs were placed in a 100 ml plastic container and the container was filled with a mixture of 8 g agar (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) dissolved in 100 ml of water in a water bath to immobilize organs during the micro-CT examination.

Micro-CT examination and image analysis

The micro-CT examination was performed using Xradia XCT-400 (Carl Zeiss Microscopy, Germany) at 120 kV and 83 µA. For each sample, 1200 projection images were recorded with an exposure time of 2 s and a magnification objective of 0.5× large-field-of-view (LFOV). The voxel size was 40 × 40 × 40 μm. The volume was reconstructed with the instrument software (XMReconstructor). Post-processing analysis was performed using CTVox volume rendering, DATAVIEWER 64-bit version (Bruker, Belgium), and Horos v2.4 software. The micro-CT images were reviewed by a human medicine cardiologist experienced in echocardiography, CT and magnetic resonance heart imaging (WM) and a veterinary cardiologist with expertise in echocardiography and postmortem heart imaging (OSJ). All hearts were evaluated in the dataset generated for each case as previously described17. It included atrioventricular and ventriculoarterial connection, all four chambers, both great arteries with the assessment of the aortic arch, all cardiac valves, arterial duct (DA), and both interatrial and interventricular septum.

Anatomopathological examination

Conventional autopsies were performed by a specialist in veterinary cardiology (OSJ) and a specialist in veterinary anatomy (KB), two medical specialists in anatomopathology (ST, MG) and a cardiothoracic surgeon (MB). A previously described standard technique for dissecting the heart for the purpose of CHD evaluation was used11,22. After the first incisions, the heart chambers were cleared of contrast and the conventional anatomopathological examination pursued.

All procedures were in line with Polish law regulations. Written permission for all examinations was granted by participating owners. The study was carried out in accordance with the standards recommended by the EU Directive 2010/63/EU for animal experiments, Good Laboratory Practice, and The Act of the Polish Parliament of 15 January 2015 on the Protection of Animals Used for Scientific or Educational Purposes (Journal of Laws 2015, item 266) as we described in Ethics declarations.

According to Polish legal regulations (The Act of the Polish Parliament of 15 January 2015 on the Protection of Animals Used for Scientific or Educational Purposes, Journal of Laws 2015, item 266), no formal ethics consent was required for this study, except for the informed consent of participants. The utilization of post-mortem tissues for scientific research does not require additional approvals under these regulations. Therefore, based on the provided legal framework, no further consents were necessary. Not a single animal was euthanized for the purpose of this study, they died of natural causes.

Data availability

Data is available on request from the corresponding author.

References

Wu, W., He, J. & Shao, X. Incidence and mortality trend of congenital heart disease at the global, regional, and national level, 1990–2017. Medicine 99, e20593 (2020).

Leirgul, E. et al. Birth prevalence of congenital heart defects in Norway 1994–2009–a nationwide study. Am. Heart J. 168, 956–964 (2014).

Wik, G. et al. Severe congenital heart defects: incidence, causes and time trends of preoperative mortality in Norway. Arch. Dis. Child. 105, 738–743 (2020).

Shanmugasundaram, S., Venkataswamy, C. & Gurusamy, U. Pathologist’s role in identifying cardiac defects-a fetal autopsy series. Cardiovasc. Pathol. 51, 107312 (2021).

Simcock, I. C. et al. Investigation of optimal sample preparation conditions with potassium triiodide and optimal imaging settings for microfocus computed tomography of excised cat hearts. Am. J. Vet. Res. 81, 326–333 (2020).

Scansen, B. A., Schneider, M. & Bonagura, J. D. Sequential segmental classification of feline congenital heart disease. J. Vet. Cardiol. 17, 10–52 (2015).

Schrope, D. P. Prevalence of congenital heart disease in 76,301 mixed-breed dogs and 57,025 mixed-breed cats. J. Vet. Cardiol. 17, 192–202 (2015).

Garncarz, M., Parzeniecka-Jaworska, M. & Szaluś-Jordanow, O. Congenital heart defects in dogs: a retrospective study of 301 dogs. Med. Weter. 73, 651–656 (2017).

Hopper, B. J., Richardson, J. L. & Lester, N. V. Spontaneous antenatal resolution of canine hydrops fetalis diagnosed by ultrasound. J. Small Anim. Pract. 45, 2–8 (2004).

Siena, G. et al. A case report of a rapid development of fetal anasarca in a canine pregnancy at term. Vet. Res. Commun. 46, 597–602 (2002).

Szaluś-Jordanow, O. et al. Hydrops fetalis caused by a complex congenital heart defect with concurrent hypoplasia of pulmonary blood vessels and lungs visualized by micro-CT in a French Bulldog. BMC Vet. Res. 20, 189 (2024).

Heng, H. G., Randall, E., Williams, K. & Johnson, C. What is your diagnosis? Hydrops Fetalis. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 239, 51–52 (2011).

Breeze, A. C. et al. Minimally-invasive fetal autopsy using magnetic resonance imaging and percutaneous organ biopsies: clinical value and comparison to conventional autopsy. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 37, 317–323 (2011).

Alderliesten, M. E., Peringa, J., van der Hulst, V. P., Blaauwgeers, H. L. & van Lith, J. M. Perinatal mortality: clinical value of postmortem magnetic resonance imaging compared with autopsy in routine obstetric practice. BJOG 110, 378–382 (2003).

Roberts, I. S. et al. Post-mortem imaging as an alternative to autopsy in the diagnosis of adult deaths: a validation study. Lancet 379, 136–142 (2012).

Kim, A. J. et al. Microcomputed tomography provides high accuracy congenital heart disease diagnosis in neonatal and fetal mice. Circ. Cardiovasc. Imaging. 6, 551–559 (2013).

Hutchinson, J. C. et al. Clinical utility of postmortem microcomputed tomography of the fetal heart: diagnostic imaging vs macroscopic dissection. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 47, 58–64 (2016).

Lombardi, C. M. et al. Postmortem microcomputed tomography (micro-CT) of small fetuses and hearts. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 44, 600–609 (2014).

Ritman, E. L. Micro-computed tomography of the lungs and pulmonary-vascular system. Proc. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2, 477–480 (2005).

Knutsen, R. H. et al. Vascular Casting of Adult and early postnatal mouse lungs for Micro-CT imaging. J. Vis. Exp. 20 https://doi.org/10.3791/61242 (2020).

Rzepliński, R. et al. Mechanism of spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage formation: an anatomical specimens-based study. Stroke 53, 3474–3480 (2022).

Erickson, L. An Approach to the examination of the fetal congenitally malformed heart at autopsy. Fetal Med. 2, 135–141 (2015).

Taweevisit, M. & Thorner, P. Cardiac findings in fetal and Pediatric autopsies: a 15-Year retrospective review. Fetal Pediatr. Pathol. 38, 14–29 (2019).

Tolia, V. N. et al. Hydrops fetalis-trends in associated diagnoses and mortality from 1997–2018. J. Perinatol. 4, 2537–2543 (2021).

Sandrini, C. et al. Accuracy of Micro-computed Tomography in Post-mortem evaluation of fetal congenital heart disease. Comparison between post-mortem Micro-CT and conventional autopsy. Front. Pediatr. 7, 92 (2019).

Sandrini, C., Boito, S., Lombardi, C. M. & Lombardi, S. Postmortem Micro-CT of human fetal Heart-A systematic literature review. J. Clin. Med. 10, 4726 (2021).

Hur, M. S., Lee, S., Oh, C. S. & Choe, Y. H. Newly-found channels in the interatrial septum of the heart by dissection, histologic evaluation, and three-dimensional microcomputed tomography. PLoS One. 16, e0246585 (2021).

Papazoglou, A. S. et al. Current clinical applications and potential perspective of micro-computed tomography in cardiovascular imaging: a systematic scoping review. Hellenic J. Cardiol. 62, 399–407 (2021).

Ruican, D., Petrescu, A. M., Istrate-Ofiţeru, A. M. & Iliescu, D. G. Postmortem evaluation of first trimester fetal heart. Curr. Health Sci. J. 48, 247–254 (2022).

Nakao, S., Atkinson, A. J., Motomochi, T., Fukunaga, D. & Dobrzynski, H. Common arterial trunk in a cat: a high-resolution morphological analysis with micro-computed tomography. J. Vet. Cardiol. 34, 8–15 (2021).

Eckner, F. A., Brown, B. W., Overll, E. & Glagov, S. Alteration of the gross dimensions of the heart and its structures by formalin fixation. A quantitative study. Virchows Arch. Pathol. Pathol. Anat. 346, 318–329 (1969).

Hołda, M. K., Hołda, J., Koziej, M., Tyrak, K. & Klimek-Piotrowska, W. The influence of fixation on the cardiac tissue in a 1-year observation of swine hearts. Anat. Histol. Embryol. 47, 501–509 (2018).

Hołda, M. K., Klimek-Piotrowska, W., Koziej, M., Piątek, K. & Hołda, J. Influence of different fixation protocols on the preservation and dimensions of cardiac tissue. J. Anat. 229, 334–340 (2016).

Ruchonnet-Metrailler, I., Bessieres, B., Bonnet, D., Vibhushan, S. & Delacourt, C. Pulmonary hypoplasia associated with congenital heart diseases: a fetal study. PLoS One. 9, e93557 (2014).

Wang, Q. et al. Pulmonary hypoplasia in fetuses with congenital conotruncal defects. Echocardiography 34, 1842–1851 (2017).

Kiraly, L., Kiraly, B., Szigeti, K., Tamas, C. Z. & Daranyi, S. Virtual museum of congenital heart defects: digitization and establishment of a database for cardiac specimens. Quant. Imaging Med. Surg. 9, 115–126 (2019).

Jarvis, J. C. & Stephenson, R. Studying the microanatomy of the heart in three dimensions: a practical update. Front. Pediatr. 1, 26 (2013).

Sawall, S. et al. Coronary micro-computed tomography angiography in mice. Sci. Rep. 10, 16866 (2020).

Armiger, L. C., Thomson, R. W., Strickett, M. G. & Barratt-Boyes, B. G. Morphology of heart valves preserved by liquid nitrogen freezing. Thorax 40 (10), 778–786 (1985).

Kozawa, S., Kakizaki, E. & Yukawa, N. Autopsy of two frozen newborn infants discovered in a home freezer. Leg. Med. 12 (4), 203–207 (2010).

Funding

The publication was (co)financed by Science development fund of the Warsaw University of Life Sciences – SGGW.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The lead author (OSJ) directed the analysis and manuscript development. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.Conceptualization OSJ; Methodology, OSJ, KB, WM, MB, AG, AMF, ZN, MM, MG, JJ, ST, TS, WŚ;Software OSJ, JJ, WŚ;Patient recruitment AG; Tissue harvesting KB, AMF, OSJ, ZN, MM; Data analysis KB, OSJ, ST, TS, MB, WM; Writing - Original draft preparation OSJ, WM; Writing - Review and editing OSJ, MC, WM;

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics declarations

All procedures were in line with Polish law regulations. Written permission for all examination was granted by participating owners. The study was carried out in accordance with the standards recommended by the EU Directive 2010/63/EU for animal experiments and Good Laboratory Practice and The Act of the Polish Parliament of 15 January 2015 on the Protection of Animals Used for Scientific or Educational Purposes (Journal of Laws 2015, item 266). According to Polish legal regulations (The Act of the Polish Parliament of 15 January 2015 on the Protection of Animals Used for Scientific or Educational Purposes, Journal of Laws 2015, item 266) no formal ethics consent was required for this study except for the informed consent of participants. Therefore, the written informed consent for participation in the study was obtained by us from all owners who decided to participate in the study. Not a single animal was euthanized for the purpose of the above study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Szaluś-Jordanow, O., Barszcz, K., Mądry, W. et al. Complex congenital heart and lung defects as a cause of hydrops fetalis in French bulldogs –micro-CT with contrast study. Sci Rep 15, 4151 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88495-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88495-2