Abstract

The material extrusion process using a heated syringe in additive manufacturing offers the advantage of fabricating various materials with a single device while being cost-effective due to the ease of material storage and management. Additionally, since the material is sealed inside the syringe, it is isolated from external contamination, allowing for the processing of materials sensitive to environmental exposure. To optimize this process, this study aimed to identify the most effective material geometry and corresponding extrusion parameters. Thermoplastic polymers (PLA, TPU, ABS) were processed into chunk, disk, and pellet geometries, and extrusion experiments were conducted. The optimal parameters, determined through preliminary experiments, included extrusion temperatures of 200 °C, 207 °C, and 240 °C, and air pressures of 300 kPa, 550 kPa, and 550 kPa for PLA, TPU, and ABS, respectively. Experimental results demonstrated that chunk geometry achieved the highest extrusion ratio and the best quality of fabricated structures, with fewer defects such as bubbles. These findings highlight the importance of maximizing the material’s contact area with the syringe wall while minimizing air exposure, providing a practical pathway to improve extrusion quality in the heated syringe additive manufacturing process.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Among the seven additive manufacturing processes defined by ISO/ASTM 52,900, the material extrusion process involves applying pressure to a material and extruding it through a nozzle or orifice to create a layered structure1. Methods for extruding materials include feeding filament-shaped materials into a heated nozzle, using air pressure to extrude liquid materials from a syringe, or heating and extruding powdered materials through a screw-driven system2. Notably, the syringe-based material extrusion process has the advantage of being applicable to various materials as long as they possess adequate flowability3. Additionally, it allows for the simultaneous extrusion of multiple materials with differing properties4,5,6. Other advantages include the sealed state of the material, which prevents contamination, the lightweight molten extrusion head that enables precise control, and the ability to use materials without requiring them to be in filament form, simplifying storage and handling. Furthermore, utilizing a heated syringe for additive manufacturing of thermoplastic and composite materials facilitates the application of common thermoplastics and can potentially reduce raw material costs by up to 20 times7.

This material extrusion process using a heated syringe has been widely used in additive manufacturing of biomaterials8,9,10,11,12,13. Additionally, research has been conducted on fabricating optical fibers by simultaneously molding two materials13. However, previous studies have shown limitations, including a lack of research on applying diverse materials7,8,9 and insufficient experimental validation6. Subsequently, research has been conducted on extruding polymer materials rather than biomaterials using a heated syringe, but quantitative experimental results have yet to be fully established14,15,16.

Therefore, this study aims to quantitatively analyze the extrusion characteristics based on the geometry of the material supplied to the syringe in a heated syringe extrusion process to identify the most suitable material supply method. To achieve this, the material geometries were categorized into three types: chunk, disk, and pellet. Polylactic Acid (PLA), Acrylonitrile Butadiene Styrene (ABS), and Thermoplastic Polyurethane (TPU), which are widely used in additive manufacturing, were processed into these geometries and supplied to the heated syringe to compare and analyze their extrusion characteristics. The analysis revealed that the chunk geometry resulted in the highest extrusion quality across all three materials, and this study focuses on the detailed findings regarding this result.

This paper is structured as follows: Sect. "Material extrusion" details the experimental setup and methodology, including the design of material geometries and the operation of the heated syringe extrusion system. Section "Experimental result" presents the experimental results, focusing on the effects of material geometry on extrusion performance and quality. Section "Conclusion" discusses the implications of the research findings for optimizing material supply methods in syringe-based extrusion processes.

Material extrusion

Geometry of materials

Figure 1 illustrates the shape of the materials used in this study, explained based on a form fabricated using TPU material. Using filaments from Hyvision Cubicon, the materials were formed into three geometries—chunk, disk, and pellet—designed to fit the internal geometry of the heated syringe. The filaments used were PLA (PLA + white, Cubicon), TPU (TPU 95 A Transparent, Cubicon) and ABS (ABS-a100 white, Cubicon). The chunk and disk geometries were fabricated using the FFF-type additive manufacturing device, specifically the Hyvision Cubicon 3DP-110 F machine. The G-code files for fabricating the chunk and disk geometries were generated using the Cubicreator4 v4.2.9 software, which is the dedicated slicer for the Cubicon 3DP-110 F.

The chunk-shaped geometry was manufactured to match the internal geometry of the syringe. Among the material geometries used in this study, the chunk form has the largest contact area with the syringe interior and the smallest surface area exposed to air. The chunk is cylindrical, with a conical projection at the end facing the nozzle, matching the syringe interior, and an identical conical indentation at the opposite end. The thermal expansion coefficients of the materials used—PLA, TPU, and ABS—are approximately 68, 100, and 81 μm/mK, respectively, compared to the syringe’s thermal expansion coefficient of 17.3 μm/mK. To minimize interference when the material expands due to heating, the outer diameter of the chunk was made 24 mm, 0.2 mm smaller than the syringe’s inner diameter. The height of the chunk matches the height of the heated section at 32.5 mm.

The disk-shaped geometry has the same structure as the chunk but was made with a height of 6.5 mm. This allows the height of five disks stacked together to equal that of the chunk. The contact area with the syringe interior is nearly the same as that of the chunk, but the surface area exposed to air is larger.

The pellet geometry is the most commonly used material form in the material extrusion process with a syringe. The pellet has the smallest contact area with the syringe interior and the largest surface area exposed to air. For this study, filaments with a diameter of 1.75 mm were cut into lengths of approximately 4 mm to create the pellet geometry.

Table 1 presents the process parameters applied for additive manufacturing of each material. Except for the infill density, the process parameters were set to the default values provided by the manufacturer’s dedicated software. Specifically, the recommended heating temperatures for extrusion are clearly specified in the Material Safety Data Sheets (MSDS) of each material17,18,19. Meanwhile, the infill density was set to 100% to maximize the internal density of the fabricated material and to minimize potential voids during the extrusion process.

Material extrusion device

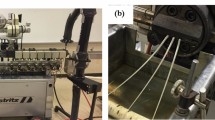

Figure 2a shows the photograph of the material extrusion equipment used in this study. The extrusion system consists of an extrusion head, a 3-axis motion stage, a pneumatic regulator, an air compressor (EWS50, Quiet Zone), and a film-attached bed capable of low-temperature heating. The 3-axis motion stage operates by moving in the X and Y axes while the Z-axis remains fixed. The extrusion head is mounted on the 3-axis motion stage, and pneumatic pressure is applied via a pneumatic dispenser and air compressor to extrude the material. The extruded material is then deposited and fabricated on a transparent film. Figure 2b illustrates the configuration of the heated syringe extrusion head applied in the material extrusion system. All materials used in the extrusion experiments were supplied into a metal syringe and sealed with a plunger. The material inside the syringe is heated by the heating element in the extrusion head until it reaches a molten state and is then extruded. The extruded material is finally discharged through a precision tapered nozzle (ANMAI), which is screw-mounted onto the metal syringe. The metal syringe is made of STS 304 stainless steel, with a total length of 130 mm, an outer diameter of 26 mm, and an inner diameter of 24.2 mm, providing a maximum capacity of 30 ml. The nozzle connection features a cylindrical structure with an inclined angle designed to enhance the material flow. The metal nozzle, made of STS 303 stainless steel, has a length of 18 mm, an outer diameter of 0.6 mm, and an inner diameter of 0.5 mm. The plunger is made of Teflon (PTFE) and designed as a cylinder with an outer diameter of 24 mm and a total length of 15 mm to fit the internal diameter of the syringe. Teflon has a thermal expansion coefficient of 100 μm/mK, which is higher than the 17.3 μm/mK of STS 304, and a low friction coefficient of 0.05–0.2, making it ideal for this application. As the plunger expands due to the heat generated during the material melting and extrusion process, it can effectively seal the upper part of the syringe. Additionally, due to its low friction coefficient, even if the plunger becomes stuck inside the metal syringe, it can still move forward under applied pressure, ensuring a consistent force is exerted on the material.

Extrusion experiment

The material extrusion experiment using a heated syringe was conducted by supplying the same amount of material in three different geometries. One chunk geometry was supplied, while five disk geometries were stacked and supplied. The pellet geometry was adjusted to match the same mass as the chunk geometry. This approach ensured that the mass of the material supplied to the syringe remained consistent, regardless of the material geometry.

Fabrication parameters

In this study, extrusion of the thermoplastic polymers required heating and pressurizing the material at the extrusion point. Since the temperature and pressure conditions necessary for extruding each material are different, experiments were conducted to determine the optimal fabricating parameters, which are presented in Table 2. For PLA, the heating temperature was set to 200 °C and the applied pressure to 300 kPa. For TPU, the heating temperature was set to 207 °C and the applied pressure to 550 kPa. For ABS, the heating temperature was 240 °C, and the applied pressure was set to 550 kPa. These fabricating parameters were established to ensure that the initial bead width during the extrusion process for each material was 0.55 mm.

The temperatures and air pressures applied to each material were determined through multiple preliminary experiments. Initially, the recommended temperatures provided by the manufacturers (PLA Plus: 220 °C, ABS A100: 230 °C, TPU Transparent: 230 °C) were set as the baseline parameters17,18,19, followed by adjustments to account for thermal deformation. Subsequently, the optimal conditions were experimentally derived by incrementally adjusting the air pressure to achieve an initial line width of 0.55 mm. Details regarding the thermal deformation of the supplied materials are further discussed in Sect. "Material-specific extrusion patterns". The process parameters were established by identifying a compromise point where deformation due to continuous heat exposure in the syringe was minimized, allowing for stable material extrusion.

The bed temperature was set to 60 °C. Although the recommended adhesion temperatures for the three thermoplastic polymers used in this study exceed 60 °C, the maximum heating capacity of the bed is limited to 60 °C. To address potential adhesion issues with the material not adhering properly to the bed, a transparent film was used. Additionally, to maintain consistency in the experiment results, the distance between the nozzle and the bed was set to 0.15 mm, and the head feed rate was consistently set at 500 mm/min.

Fabrication geometry

To compare the changes in extruded material geometry and maximum extrusion volume based on each material’s geometry, a continuous band geometry was formed. As shown in Fig. 3a, the continuous band geometry was created consistently, regardless of the material type or geometry. Specifically, the extrusion head was moved -y by 20 mm, x by 0.55 mm, y by 20 mm again, and x by another 0.55 mm while extruding material, repeating this process to create a band 280 mm long in the x-direction. Once one band geometry was completed, the process was repeated until the material was no longer extruded. Subsequently, to verify whether the differences observed in the extrusion results for each material geometry were consistent during layered extrusion, a cuboid geometry was formed. As shown in Fig. 3b, the cuboid geometry was layered by repeating the extrusion of cross-sections, independent of the material type or geometry. First, a square outline with a side length of 20 mm was formed, and the extrusion head was moved to an inner corner of the square without extruding material. Then, while extruding, the head was moved -y by 19 mm, x by 1.1 mm, y by 19 mm again, and x by 1.1 mm, repeating this process until the head moved 19 mm in the x-direction to form the cross-section. During this process, the line width was consistently set to 0.55 mm in the program. After one layer was completed, the next layer was formed by rotating the cross-Section 90 degrees and repeating the process. The layer height was set to 0.15 mm, and this process was continued until the material was no longer extruded.

Experimental result

Extrusion experiment

To compare the extruded material geometry and maximum extrusion volume based on each material geometry, continuous band geometries and cuboid geometries were layer-formed and compared. The mass of the material supplied to the heated syringe was compared to the mass of the extruded material. Each experiment was repeated three times for every case, and the average value of the results was determined as the final outcome.

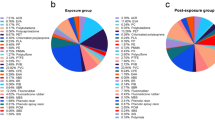

Fabricating continuous band

The mass of material supplied for each geometry when using PLA was 1.759 g for chunk, 1.789 g for disk, and 1.759 g for pellet. After the experiment, the average extruded mass for the chunk geometry was 1.716 g, with a band length of 3.5 m and a duration of 281 min. For the disk geometry, the average extruded mass was 1.55 g, with a band length of 3.8 m and a duration of 305 min. For the pellet geometry, the average extruded mass was 0.969 g, with a band length of 1.96 m and a duration of 158 min. When comparing extrusion ratios, the chunk, disk, and pellet geometries yielded 97.55%, 86.64%, and 54.06%, respectively, with the chunk geometry having the highest extrusion ratio. The extrusion ratio is defined as the mass of extruded material relative to the mass of supplied material. When comparing extrusion patterns, the standard deviations of the extrusion amount for the bands, excluding the last line, were 0.045 g, 0.046 g, and 0.02 g, respectively. Additionally, PLA showed lower viscosity when heated compared to other materials, making it difficult to maintain consistent line width. As a result, wider-than-intended extrusion widths were observed. Figure 4 shows a photograph, magnified 100 times, of the over-extruded section during the PLA extrusion experiment.

For TPU, the mass of material supplied for each geometry was 1.478 g for chunk, 1.509 g for disk, and 1.478 g for pellet. After the experiment, the average extruded mass for the chunk geometry was 1.403 g, with a band length of 3.64 m and a duration of 293 min. For the disk geometry, the average extruded mass was 1.363 g, with a band length of 3.08 m and a duration of 247 min. For the pellet geometry, the average extruded mass was 1.012 g, with a band length of 1.54 m and a duration of 124 min. When comparing extrusion ratios, the chunk, disk, and pellet geometries yielded 94.9%, 90.34%, and 68.48%, respectively, with the chunk geometry again having the highest extrusion ratio. The standard deviations of the extrusion amount for the bands, excluding the last line, were 0.031 g, 0.038 g, and 0.064 g, respectively. Furthermore, for TPU, the initial line width of 0.55 mm was maintained relatively well until the latter part of the experiment, which is believed to be due to TPU’s high viscosity.

For ABS, the mass of material supplied for each geometry was 1.523 g for chunk, 1.543 g for disk, and 1.523 g for pellet. After the experiment, the average extruded mass for the chunk geometry was 1.434 g, with a band length of 9.96 m and a duration of 800 min. For the disk geometry, the average extruded mass was 1.477 g, with a band length of 10.25 m and a duration of 823 min. For the pellet geometry, the average extruded mass was 0.12 g, with a band length of 0.2 m and a duration of 16 min. When comparing extrusion ratios, the chunk, disk, and pellet geometries yielded 94.17%, 95.71%, and 7.83%, respectively, with the disk geometry exhibiting the highest extrusion ratio, unlike the other materials. The standard deviations of the extrusion amount for the bands, excluding the last line, were 0.006 g, 0.0045 g, and 0.0087 g, respectively. For ABS, a narrower extrusion width was observed, which was attributed to the limitations of the equipment used in the experiment, where the heating temperature and air pressure could not be increased further. As a result, the pellet geometry exhibited irregular extrusion from the beginning, making consistent layered fabrication impossible.

Fabricating cuboid

The mass of material supplied for each geometry when using PLA was 1.759 g for chunk, 1.789 g for disk, and 1.759 g for pellet, identical to the continuous band extrusion experiment. The extruded masses were 1.705 g for chunk, 1.666 g for disk, and 0.927 g for pellet, with extrusion ratios of 96.92%, 93.1%, and 52.71%, respectively.

For TPU, the mass of material supplied for each geometry was 1.478 g for chunk, 1.509 g for disk, and 1.478 g for pellet, again matching the continuous band extrusion experiment. The extruded masses were 1.377 g for chunk, 1.314 g for disk, and 0.893 g for pellet, with extrusion ratios of 93.14%, 87.06%, and 60.41%, respectively.

For ABS, the mass of material supplied was 1.523 g for chunk and 1.543 g for disk, also consistent with the continuous band extrusion experiment. The extruded masses were 1.469 g for chunk and 1.507 g for disk, with extrusion ratios of 96.44% for chunk and 97.69% for disk. Pellet extrusion was not feasible for ABS.

Additionally, it was observed that the results of the cuboid layered fabrication experiment were generally consistent with those from the continuous band extrusion experiment. Therefore, the extrusion characteristics identified for each material type and geometry in the continuous band experiment are expected to behave similarly during layer-by-layer extrusion.

Table 3 summarizes the overall experimental results, while Fig. 5 presents a comparison of the extrusion ratios from the continuous band extrusion experiment and the cuboid layered fabrication experiment.

Material-specific extrusion patterns

Among the three materials covered in this study, only PLA did not exhibit visible thermal deformation. On average, thermal deformation in TPU was observed 70 min after extrusion began, while in ABS, it started around 160 min. However, when considering the overall experimental results, the extrusion ratios of ABS and TPU, which underwent thermal deformation, exhibited consistent trends with the extrusion ratios of PLA, which did not undergo any deformation. For all three materials, the extrusion ratios for chunk and disk geometries were significantly higher than those for the pellet form. This indicates that the thermal deformation observed in different material types did not affect the differences in extrusion ratios based on material geometry. Figure 6 presents photographs of cuboidal specimens of various thermoplastics supplied in chunk form, captured at 100x magnification using an electron microscope. The photographs were taken at 90 min and 180 min after the start of the extrusion process. In the case of the PLA specimens, no visible thermal deformation was observed even as the extrusion time progressed. In contrast, the ABS and TPU specimens exhibited pronounced thermal deformation as the extrusion time increased.

Geometry-specific extrusion patterns

Bubble formation

Upon examining the fabricated band geometry under a microscope, qualitative differences were observed depending on the geometry of the supplied material. It was found that the chunk geometry contained the fewest bubbles, followed by the disk and pellet geometries. This is believed to be due to the varying surface areas exposed to air inside the syringe, with larger surface areas leading to more air being incorporated, resulting in a higher likelihood of bubble formation. Figure 7 shows magnified (100x) images of the TPU specimens in chunk, disk, and pellet geometries, taken 90 min after the extrusion experiment began.

Extrusion ratio

When comparing the results of the extrusion experiments by material type and geometry, it was observed that in PLA and TPU, the chunk geometry had a higher extrusion volume than the disk geometry, while in ABS, the disk geometry exhibited a higher extrusion volume than the chunk geometry. This indicates that the extrusion behavior can vary depending on the material supply geometry for different materials.

The specific data supporting these observations are presented in Table 3, and the trends are visually represented in Fig. 5. From these data, it is evident that the extrusion volume differences between chunk and disk geometries are relatively small for all three materials, indicating similar extrusion performance. However, the pellet geometry demonstrated significantly lower extrusion ratios under the same conditions or failed to form properly altogether.

The difference between the chunk/disk geometries and the pellet geometry lies in the degree of contact between the material and the syringe wall. Therefore, it can be concluded that the greater the contact area between the material and the syringe wall, the greater the mass and volume of the fabricated shape for the same material mass. Figures 8 and 9 present representative images of the specimens from the continuous band fabrication experiment and the cuboid layered fabrication experiment, respectively.

Conclusion

In this study, the goal was to identify the optimal material geometry for the material extrusion additive manufacturing process using a heated syringe. To achieve this, thermoplastic polymers were selected, and extrusion experiments were conducted with materials categorized into chunk, disk, and pellet geometries, with the results compared and analyzed.

The experimental results showed that for all three materials, extrusion volumes significantly increased when the material was supplied in chunk or disk form compared to pellet form. This indicates that larger fabricated structures can be achieved when the contact area between the material and the heated syringe wall is maximized. Additionally, it was observed that objects fabricated with chunk geometries contained fewer bubbles than those made with disk geometries, and disk geometries contained fewer bubbles than pellet geometries. Therefore, the conclusion can be drawn that minimizing the surface area of the material exposed to air improves the quality of the fabricated object.

Furthermore, this study demonstrated that supplying materials in chunk form not only improves molding quality for PLA, ABS, and TPU but also provides insights into overcoming the limitations of the syringe-based extrusion method, such as reduced molding quality. This finding suggests that the use of chunk-shaped materials can serve as a promising approach to enhance the quality of fabricated objects for a broader range of materials, including those that are high-cost, sensitive, or difficult to process into filament form.

As a result, the most suitable material supply method for the heated syringe extrusion process is one in which the material has maximum contact with the syringe wall, minimizing exposure to air while maintaining high-quality molding.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

ISO/ASTM 52900. Additive manufacturing (2021).

Gonzalez-Gutierrez, J. et al. Additive Manufacturing of Metallic and Ceramic Components by the material extrusion of highly-filled polymers: A review and future perspectives. Materials 11 (5), 840. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma11050840 (2018).

Saadi, M. A. S. R. et al. Direct Ink writing: A 3D printing technology for diverse materials, chemistry – A European. 34 (28), 165. https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.202108855 (2022).

Neumann, T. V. & Dickey, M. D. Liquid metal direct write and 3D printing: A review. Adv. Mater. Technol. Hall Fame. 5 (9), 170. https://doi.org/10.1002/admt.202000070 (2020).

James, E., Smay, J., Cesarano & Lewis, J. A. Colloidal inks for directed assembly of 3-D periodic structures. Langmuir 18 (14), 5429–5437. https://doi.org/10.1021/la0257135 (2002).

Sohn, I. S. & Park, C. W. Diffusion-assisted coextrusion process for the fabrication of graded-index plastic optical fibers. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 40 (17), 3740–3748. https://doi.org/10.1021/ie0009536 (2001).

Chad, E. et al. Structure and mechanical behavior of big area additive manufacturing (BAAM) materials. Rapid Prototyp. J. 23 (1), 1355–2546. https://doi.org/10.1108/RPJ-12-2015-0183 (2017).

Kim, J. Y. et al. Cell adhesion and proliferation evaluation of SFF-based biodegradable scaffolds fabricated using a multi-head deposition system. Biofabrication 1 (1), 015002 (2009).

Kim, J. Y., Lee, T. J., Cho, D. W. & Kim, B. S. Solid free-form fabrication-based PCL/HA scaffolds fabricated with a multi-head deposition system for bone tissue engineering. J. Biomater. Sci. Polym. Ed. 21 (6–7), 951–962 (2010).

Shim, J. H. et al. Effect of thermal degradation of SFF-based PLGA scaffolds fabricated using a multi-head deposition system followed by change of cell growth rate. J. Biomater. Sci. Polym. Ed. 21 (8-9), 1069–1080 (2010).

Shim, J. H., Kim, J. Y., Park, M., Park, J. & Cho, D. W. Development of a hybrid scaffold with synthetic biomaterials and hydrogel using solid freeform fabrication technology. Biofabrication 3 (3), 034102 (2011).

Kuang, X. et al. 3D Printing of highly stretchable, shape-memory, and self-healing elastomer toward novel 4D printing. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 10 (8), 7381–7388. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.7b18265 (2018).

Ansari, M. A. A. et al. Engineering biomaterials to 3D-print scaffolds for bone regeneration: Practical and theoretical consideration. Biomaterials Sci. (11), 2789–2816. https://doi.org/10.1039/D2BM00035K (2022).

Yu, K. Y., Park, C. Y. & Lee, I. H. Primary study of thermoplastic polyurethane (TPU) for additive manufacturing using heated syringe. in Proceedings of the KSMPE Conference (2023).

Yu, K. Y., Jeong, W. J., Park, C. Y. & Lee, I. H. Study of thermoplastic polyurethane (TPU) extrusion using metal barrel for material extrusion. in Proceedings of the KSMPE Conference (2023).

Goo, D. Y., Yu, K. Y. & Lee, I. H. Study on the material extrusion of additive manufacturing using heating syringe. in Proceedings of the KSMPE Conference (2024).

TLC Korea Co., Ltd. Safety Data Sheet: Advanced ABS (AABS) (Retrieved from the manufacturer’s documentation, 2016).

TLC Korea Co., Ltd. Safety Data Sheet: BG-4800 (PLA Compound Resin) (Retrieved from the manufacturer’s documentation, 2017).

Dongguan Zhehan Plastic & Metal Manufactory Co., Ltd. Material Safety Data Sheet: Flexible TPU Filament (Retrieved from the manufacturer’s documentation, 2016).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF), funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT (Grant No. 2022R1A2C1091587).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.Y. Yu designed the study, wrote the manuscript, translated the content, performed data analysis, and conducted final revisions. D.Y. Goo collected data, prepared figures, and drafted the initial manuscript. I.H. Lee reviewed and edited the manuscript, contributed to data analysis, provided final revisions, and supported the research. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yu, K.Y., Goo, D.Y. & Lee, I.H. Research on the extrusion characteristics for the geometry of materials in material extrusion process using heating syringe. Sci Rep 15, 11292 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88512-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88512-4