Abstract

Overuse of synthetic pesticides causes problems for humans and the environment or leads to insect resistance to insecticides, so plant extracts and essential oils have gained popularity as an environmentally acceptable alternative to chemical pesticides. This study investigated the toxicity of Delonix regia leaf and seed extracts, protein patterns, and genetic distance analysis against the 5th instar larvae of cotton leafworm, Spodoptera littoralis Boisaduval. Methanol, petroleum ether, and acetone extracts of leaves and seeds of D. regia were used to coat castor leaves for ingestion by the 5th instar of S. littoralis larvae. The seeds’ methanol and petroleum ether extracts were the most effective (100 and 98 Mortality%), with LC50 values of 0.887 and 1.795 g/L, respectively, 24 h post-treatments. Data showed that D. regia extracts affected consequences of protein changes compared to untreated S. littoralis larvae resulted in genetic changes, as well as inhibition of the insect’s important α-amylases, forming protein complexes, and influencing normal growth and development. GC-MS analysis of the chemical composition of the seed extract revealed 18 compounds with high levels of stigmasterol, 2-methyl-4-vinylphenol, benzoic acid, 3-hydroxy, and squalene with percentages of 43.07%, 21.33%, 14.51%, and 14.12%, respectively. As a result, we concluded that D. regia seed extracts had the potential to control Spodoptera littoralis larvae.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With 30 valid and recognized polyphagous species, the widespread genus Spodoptera Guenée 1852 attacks diverse grain crops, pasture lands, and vegetable crops worldwide1,2. This genus includes several species that cause extensive damage to a broad range of essential crops, including cotton, maize, soybean, rice, cabbage, tomato, lettuce, pepper, strawberry, eggplant, tobacco, and sugar beet3,4,5. In addition to the primary insect complex consisting of S. exigua, S. frugiperda, and S. litura, the Egyptian cotton leafworm, S. littoralis, poses a threat to the production of the aforementioned crops6. With a widespread distribution in Egypt and other African nations, S. littoralis has emerged as one of the most dangerous pests in this region, necessitating the search for nontraditional and conventional pesticides within the context of environmental concern7. In Egypt, the Egyptian cotton leafworm, S. littoralis (Boisd.), is considered a major destructive pest, causing massive economic damage to ornamentals and orchard trees8, In addition to cotton, vegetables, and fruits, the Egyptian cotton leafworm, S. littoralis, is considered a major destructive pest in Egypt9,10. Spodoptera littoralis, which gives priority to the larval stage, has a host range of more than 100 plants and causes a 50% loss in yield11,12. Over the past years, S. littoralis has developed resistance against several synthetic insecticides and some biocontrol agents, such as Bacillus thuringiensis, which challenged their various control plans13.

Globally, there is a direction to find alternatives to synthetic pesticides for managing insect pests in order to avoid their disadvantages, such as human and environmental problems14,15,16 and the impact on the non–target organisms17,18. In addition to the biological control and intercropping19,20, the use of botanical insecticides in the ancient civilizations, including Egypt, India, Greece, and China21,22, as well as more than 150 years ago in Europe and North America appears to be a solid foundation23.

Two millennia ago, ancient Egyptian, Chinese, Greek, and Indian civilizations documented botanical extracts as effective substances in the control of pests22. Generally, four types of botanicals are used in insect control, viz. pyrethrum, rotenone, neem, and essential oils23. Various plant extracts of the royal poinciana, Delonix regia, have been found to be characterized by insecticidal and biocidal activities against many insects and acarines.

The royal poinciana, D. regia (Bojer ex Hook) Raffin (Family: Fabaceae), is native to India, Africa, Madagascar, and Northern Australia. The plant was traditionally used to treat a variety of diseases, including malaria, jaundice, ulcers, wound arthritis, and diarrhea24. In addition, its abundance of flavonoids, saponins, tannins, steroids, alkaloids, triterpenoids, and carotene hydrocarbons contributed to its application in the control of numerous insect and acarine pests, such as the Indian white termite, Odontotermes obesus, the German cockroach, Blattella germanica, the deer tick, Ixodes scapularis25, the diamondback moth, Plutella xylostella26, the maize weevil, Sitophilus zeamais27, the southern house mosquito, Culex quinquefasciatus28, the pepper weevil, Anthonomus eugenii29, the cowpea aphid, Aphis craccivora30.

In a comparative study against the destructive fifth larval instar of S. littoralis (Boisd.), we evaluated the leaf and seed extracts of D. regia (Bojer ex Hook) using various solvents, including petroleum ether, methanol, and acetone. Moreover, the effects of genetic variations caused by these applications relative to untreated larvae were reported. To our knowledge, this is the first study to assess the extracts of D. regia as a control botanical alternative against the Egyptian cotton leaf worms, S. littoralis.

Materials and methods

Plant materials and extraction of chemical constituents

The collected plant was identified and authenticated by Dr. Reem Hamdy, a plant taxonomy consultant at the Cairo herbarium, and a voucher specimen was deposited at the herbarium of the Plant Department, Faculty of Science, Cairo University, under the code: (PH 11-09-2024). Leaves and seeds of the royal poinciana, D. regia (Caesalpinioideae, Fabaceae) were collected from the North Coast, Egypt (31° 12’ 37.8” N; 29° 54’ 45.108” E) (Fig. 1). For the extraction of chemical components from the leaves, three different solvents (petroleum ether, acetone, and methanol) were used, whereas only petroleum ether and methanol were used for the extraction of the components from the seeds since the acetone has the same ability to petroleum ether in extracting D. regia seed components. A Soxhlet extractor (Sklo Union, Teplice, Czech Republic) was utilized for eight continuous hours to extract the chemical components from 150 g of the crushed seeds and 100 g of the leaves. Excess solvents were extracted with the aid of an HS–3000 electric aspirator (Bibby Scientific Ltd., Staffordshire, UK). Stock extractions were then centrifuged for 20 min at 1,000 rpm to separate the extracted substances.

Experimental insects

Larvae of the Egyptian cotton leafworm, S. littoralis (Boisduval, 1833), were obtained from the laboratory colonies of the Department of Applied Entomology & Zoology, Faculty of Agriculture, Alexandria University, Egypt (31° 12’ 0.3312” N; 29° 55’ 7.4604” E). Under controlled laboratory conditions (25 ± 2 °C and 65 ± 5 RH%; 12 h light: 12 h darkness), the larvae were reared by feeding on castor plant leaves, Ricinus communis. The larvae of the fifth instar were subjected to starvation six h prior to the bioassay31.

Bioassay

A total of 750 larval S. littoralis was processed to evaluate D. regia extracts. The petroleum ether and methanolic extracts of both the seeds and the leaves were prepared in a series of five concentrations (1, 5, 10, 20, and 50 g/L). Every concentration was applied to three replicates of ten larvae each. Methanol, acetone, and petroleum ether were used solely as controls. Fresh castor leaves were submerged in each concentration for three min to ensure a uniform coating of the extract on the castor leaves, then allowed to dry before the introduction to be ingested by the starved larvae in Petri–dishes. The mortality rates were evaluated after 24, 48, and 72 h post-feeding. Specimens of the control and treated larvae were preserved in 70% ethanol for further analysis. Mortality values were corrected according to the corrected Abbott formula32

Where:

mt = mortality in treatment.

mta = mortality in witness treatment.

Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS)

GC-MS analyses of organic crude extracts of the seeds of D. regia (the most effective extracts) were performed by mixing two ml of the oil thoroughly with 7 ml of alcoholic sodium hydroxide (C2H7NaO2), followed by addition of 7 ml alcoholic sulfuric acid with well-vortexing and kept overnight. One ml of sodium chloride was then added to the mixture and mixed well. Two ml of methanol were added to the mixture and vortexed, followed by dilution in 5 ml of diethyl ether and dried by anhydrous sodium sulphite (Na2SO3). One µl of the diluted mixture was placed in the GC-MS vial. The pH of the extraction buffer in the Native electrophoretic protein pattern is 7.8. Various analyses was performed with the help of Shimadzo GC-MS-QP2010 Ultra machine (Kawasaki-shi, Japan) with a RTX-5MS column (30 m, length ; 0.25 mm diameter; 0.25 μm, thickness) in 150 °C oven temperature, 250 °C injection temperature with injection mode of split; total flow: 55 ml/min; linear velocity pressure: 142 KPa; linear velocity: 49.6 cm/sec.; column flow: 1.74 ml/ sec. and purge flow: 3.5 ml/min. Helium have been used in the GCMS as a carrier gas with 1 ml/min flow rate.

Native electrophoretic protein pattern

Weights of 0.2 gm of every preserved larva/each treatment were rapidly frozen in liquid nitrogen, followed by homogenization with one ml of the extraction buffer. The homogenates were centrifuged for 5 min at 10,000 rpm, and the supernatants were transferred into another tube. Determination of the total protein in all pooled samples was performed based on the method previously described by Bradford33.

Mixtures of homogenates samples and loading buffers were run in the vertical slab polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) according to Laemmli34 using mini–gel electrophoresis unit (BioRad, USA) with 180 V/ 30 min followed by 150 V/ 45 min. A modification of lacking SDS in gel 8% (Acrylamide/Bis 30% T, 2.67% C; Tris–HCL 1.5 M, ph 8.8; Tris–HCL 0.5 M, ph 6.8; Ammonium persulfate 10%; and N, N,M, M– Tetramethylethylnediamine (TEMED) and running buffer (Tris- (24 mM) and glycine (194 mM)) were to determine the relative molecular weight of isolated proteins. After documentation, protein bands were visualized by staining with Coomassie Brilliant Blue G–250 and destained overnight with 7% (v/v) glacial acetic acid35. The relative mobilities (Rf), band intensity, percent of band intensity (B%), and band quantity (Qty) of the electrophoretically separated bands were determined.

Photographing, scanning, and band analysis were performed using Quantity One software (Version 4.6.2) to determine the relative motilities and amounts of the peptide chains as well as scanned graphical presentation of the fractionated bands of each lane. Additionally, it is used to determine percentages of the similarity index (SI%) and genetic distance (GD%).

Statistical analysis

We applied the one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for data analysis. Multiple comparisons were carried out applying Tukey’s test and probit analysis for calculating the lethal values using the computer program MedCalc statistical software v. 19.2.6 (MedCalc Software Ltd., Ostend, Belgium)36.

Results

Larvicidal activity of D. Regia extracts on S. littoralis larvae

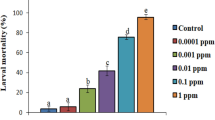

The study evaluated the larvicidal effects of D. regia extracts against the 5th larval instar of S. littoralis, suggesting an insecticidal activity against S. littoralis larvae. The data of this study demonstrated that the methanol extract of D. regia seeds had stronger harmful effects than other plant extracts against S. littoralis. The mortality percent (MO%) of S. littoralis treated with 20 g/L methanol seed extracts of D. regia at 24 h post-treatment (PT) was complete (Fig. 2) with corresponding LC50 (50%, median lethal concentration) = 0.887 g/L (Table 1), while the corresponding values for D. regia seeds (Pe), D. regia leaves (Pe), D. regia leaves (M), and D. regia leaves (A) extracts were of LC50 values = 1.795, 3.37, 5.876, and 18.787 g/L, respectively, 24 h PT.

The larval mortality was maximum after 72 h of PT, while the mortality reached to the maximum at 20 g/L in plant extracts. In terms of fatal concentrations, D. regia methanol and petroleum ether seed extracts were revealed to be the most effective against S. littoralis larvae (LC50 = 0.587 and 1.251 g/L), followed by the petroleum ether extract of the leaves (2.661 g/L), the methanol extract of the leaves (3.726 g/L), and the acetone extract of the leaves (9.798 g/L) (Table 1). The application of solvents as control treatments resulted in no recorded mortalities. Several morphological irregularities were observed either in the treated larvae or in the pupation of the survivors (Figs. 3 and 4).

GC-MS analysis

GC-MS analysis of the chemical composition of the seed extract revealed a cocktail of 18 compounds with eight substances of insecticidal properties. D. regia seed methanolic contains high levels of Stigmasterol, 2-Methoxy-4-vinylphenol, Benzoic acid, 3-hydroxy, and Squalene with percentages of 43.07%, 21.33%, 14.51%, and 14.12%, respectively (Table 2).

Native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

The absence of some protein bands was observed in all the treatments compared to the control. The methanolic extract of D. regia seeds (T2) was the most effective, resulting in the absence of four different protein bands. The petroleum ether of the seeds (T1) was in second place, and it caused the disappearance of three protein bands. Both the methanolic (T4) and petroleum ether (T3), and acetone (T5) leaf extracts caused the absence of one protein (Fig. 5). Related data of relative mobility, band intensity, and band quantity are depicted in Table 3.

Native electrophoretic protein pattern of the control and treated larvae of S. littoralis (M: molecular marker; C: control; T1: Petroleum ether extract of D. regia seeds; T2: Methanolic extract of D. regia seeds; T3: Petroleum ether extract of D. regia leaves; T4: Methanolic extract of D. regia leaves; T5: Acetone extract of D. regia leaves).

For the first two protein bands, larvae treated with the methanolic extract of the leaves (T4) were the least mobile (0.09 and 0.148, respectively). The petroleum ether treatment of the leaves caused a decrease in the mobility of the third (0.34), fourth (0.58), and fifth bands (0.64). No significant differences were detected between the relative mobilities of other protein bands of the treated larvae (Table 3).

Similarity index and genetic distance

Similarity–wise calculations revealed that T4 (methanolic extract of the leaves) was the least similar to control by only 58.10%, whereas T3 (petroleum ether of the leaves) showed the highest similarity to control by 74.60%. In–between the treatments, the highest similarity pattern was between T5 and T3 by 80.70%. Genetic distances between band patterns ranged between 19.30% and 80.50% (Table 4).

Discussion

The present study revealed promising insecticidal activities of D. regia different extracts against S. littoralis larvae. The study showed that the methanol extract of D. regia seeds was more harmful to S. littoralis than other plant extracts. Methanol seed extracts of D. regia killed all of the S. littoralis stage in 24 h, with an LC50 value of 0.887 g/L. The maximum mortality occurred at a concentration of 20 g/L in the plant extracts after 72 h post-treatment. Methanol (LC50 = 0.587 g/L) and petroleum ether (1.251 g/L) were the two seed extracts from D. regia that killed the most S. littoralis larvae. The petroleum ether leaf extract (2.661 g/L), the methanol leaf extract (3.726 g/L), and the acetone leaf extract (9.798 g/L) came next.

The extraction yield and phytochemical composition were influenced by the polarity of the extracting solvents. The use of different solvents resulted in varying extraction yields. Changes in the polarity of the solvent can help explain why the concentration of bioactive compounds in the extract changed. This is due to the presence of substantial amounts of polar molecules in plant components that are soluble in highly polar liquids. A different study found that the acetone extract had more alkanes, flavonoids, terpenes, ketones, and phenols than the water-based extract37.

Phytochemical analyses showed several components that serve as bioactive secondary metabolites in D. regia extract, including tannins, sterols, flavonoids, saponins, alkaloids, steroids, anthocyanins, triterpenoides, and carotene hydrocarbons24. Earlier reports approved the insecticidal activity of D. regia extract against beetles and caterpillars (LC50 = 5.7 g/L)38, Pericallia ricini (LC50 = 9.47 g/L)39, Anopheles gambiae (LC50 = 7.16 g/L)40, the teak defoliator, Hyblaea puera ( LC50 = 14.58 g/L)41. In addition to the toxicity, an antifeedant effect was reported when applied against the pulse beetle, Callosobruchus maculatus42. Apparently, D. regia extracts have topical insecticidal properties43; however, the cytotoxic properties, including the oxidative stress and decreasing the cell viability could be the main reason for the mortalities caused by carbon tetrachloride and dichloromethane fractions of D. regia extracts have been reported as cytotoxic components44. Previous studies have reported that the essential oils have a blocking effect on the insect spiracles, leading to the strangulation and death of the insect through their topical toxicity45,46. Other effects of some plant extracts included apparently ovicidal actions, resulting in decreased hatchability or oviposition rates as a result of impeding the adult insect’s locomotion and mating success46.

Based on earlier studies regarding the phytoconstituents of D. regia, seeds of this plant contain high concentrations of fatty acids viz. linoleic, heptanoic, octanoic, myristic, palmitic, stearic, and oleic acids that are absent in the leaves47. These acids have been previously investigated in terms of their toxicological effects on some insect pests, including spiny bollworm and Earias insulana, as well as whether they decrease or increase the total protein content of the tested insects out of the normal levels. It affects protein synthesis through the formation of the protein complex, influencing the insect’s growth, development, performing vital activities, and eventual death48. Moreover, various fatty acids and esters of plant origin were previously showed toxic effects against the codling moth, Cydia pomonella49, the southern house mosquito, Culex quinquefasciatus50, the malaria vector, Anopheles funestus, and the Egyptian cotton leaf worms, S. littoralis itself51,52. The results of GC-Mass analysis of the methanolic seed extracts of D. regia reported high contain of Stigmasterol, 2-Methoxy-4-vinylphenol, Benzoic acid, 3-hydroxy and Squalene. Stigmasterol has been reported to have an inhibitory influence on the activity of one of the most familiar detoxifying enzymes in insects, the acetylcholinesterase (AChE)53, suppressing the insect defense action in response to toxic substances and explaining the potential insecticidal efficacy on S. littoralis larvae of this study. Likewise, the 2-Methoxy-4-vinylphenol was reported as a compound with insecticidal activity54.

In general, sterols such as β-sitosterol, stigmasterol, and sitosterol present in both seeds and leaves of D. regia are responsible for the insecticidal properties of fixed essential oils55. The tannins concentration of D. regia seeds and leaves as well56 may be a determining factor in insecticidal and biocidal activity. Since they have been reported to be of hardening influence, leading to the limitation of cell transfer and eventually death, apart from their larvicidal properties, affecting the growth, development, and fecundity of many phytophagous insects57,58.

Phytosterols, like stigmasterol and alkanols, control the killing of larvae. They can be found in the bioactive part of plants like Delonix regia, Chromolaena odorata, Ricinus communis and many plants. Stigmasterol and 1-hexacosanol were the primary chemicals responsible for killing the insect larvae, as they caused damage to the nerve cells. Researchers found that stigmasterol and 1-hexacosanol both stop acetylcholinesterase activity in Culex quinquefasciatus and Aedes aegypti. It was shown to block acetylcholinesterase both in the laboratory with recombinant acetylcholinesterase and in the wild with Culex and Aedes larval homogenates. Electrophysiological studies using electroantennography have shown that these substances make the brain respond more strongly (Gade et al., 2017).

Likewise, flavonoids and isoflavonoids59, significantly influence the insect’s behavior, development, and growth60. Falvonoides along and saponins previously showed increased mortality of the gypsy moth, Lymantria dispar61, the tobacco armyworm, S. litura, the cowpea seed beetle, C. maculatus62, the pea aphid, Acyrthosiphon pisum (Goławska et al. 2014). Flavonoids may kill nematodes by blocking acetylcholinesterase (AChE). This is because nematodes, insects, and mammals share many neurotransmitters, such as acetylcholine, serotonin, and glutamate63. Botanical extracts are also known by their side effects other than toxicants, including antifeedants, deterrents, and anti-growth/development64,65, resulting in death eventually due to starvation and/or growth failure. This finding might also explain the behavioral changes, anomalies, and molting failure of the treated larvae in this study.

Variations in lethality between the different treatments could be either due to the plant part and the concentrations of the components inside each or due to the solvent used. Although the plant’s metabolites vary in their chemical nature and composition according to the species, these properties are fixed in all the parts of the same plant species, and basically, secondary metabolites are the main components66. The concentrations of these secondary metabolites also vary according to the plant part67, which might explain the more potent efficacy of the D. regia seed extracts than the leaf extracts in the obtained results. Furthermore, the nature of the solvent used is apparently playing a role in determining the final efficacy of the plant extract as it either varies in the efficiency of extracting the bioactive molecules from the plant or acts as a synergistic factor in some cases68. Methanol appears to be the optimal solvent for maximizing plant extraction yield in addition to the synergistic effect it plays69,70. This finding may explain why methanolic extracts demonstrated the best results in the current study, followed by other solvents.

Molecularly, the protein fraction (RF) of D. regia seeds that contain cationic proteins evidently inhibits the α–amylase enzymes being produced by insects, such as C. maculatus (by 97.7%), Anthonomus grandis (by 84.7%) and Acanthoscelides obtectus (by 48.5%) with more specificity to insect α–amylase and no inhibitory effects on the serine proteinases71. Delonix regia has been proven to produce diversified inhibitors which perhaps involved in the impact on the insect’s defense mechanisms71. The alpha-amylases are principally digestive enzymes involved in the preliminary pathway of maltopolysaccaride digestion and are produced with the help of multiple gene copies. Multiple copying of insect amylases enables insects to organize their tissue- and stage-specific regulation, improve their enzymological abilities, and circumvent the plants’ inhibitory defenses. The inhibition of these enzymes by inhibitors produced by D. regia plants may be the primary cause of the failure of these processes and eventual insect death72. The appearance and disappearance of proteins produced by S. littoralis larvae undoubtedly explain the hidden effect of the D. regia extracts’ mode of action. Consequently, in the following experiment, we will design a study to investigate the nature of these products.

In the present study, we demonstrated a botanical alternative to conventional synthetic insecticides for controlling one of the main destructive phytophagous insects, S. littoralis. The toxicological effect of D. regia extracts on S. littoralis larvae was apparently not due to the topical application mentioned above. However, the effects of genetic and protein production reactions, such as the inhibition of the insect’s α–amylases by these extracts, could be a determining factor in the development and survival of the insect in terms of anti–feeding (the inhibition of their feeding ability hours before the death), aggregation behavior (formation of mass number of larvae), immobility (lack of regular active movement), failure of stage–regulation or death actions (elongation of the larval stage period greater than the normal) as observed and discussed in the current study; however, further investigations regarding the α–amylases activity are needed to confirm this fact. Therefore, we recommend additional research into D. regia extracts to be used as botanicals with insecticidal properties against various insects.

This study attempted to manage S. littoralis, which is an economically significant pest in Egypt. Delonix regia’s various extracts of leaves and seeds were found promising in suppressing such insects with maximum impact of the methanolic seed extract (LC50 of 0.887 g/L). Additionally, several genetic and protein repercussions were noticed by the Native-PAGE profile, demanding future follow-ups of the current work. Therefore, we would encourage future research into the use and formulations of D. regia extracts against insect pests.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Pogue, M. G. A World Revision of the Genus Spodoptera Guenée (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Vol. 43 (American Entomological Society Philadelphia, 2002).

Meagher, R. L., Brambila, J. & Hung, E. Monitoring for exotic spodoptera species (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) in Florida. Fla. Entomol. 91, 517–522 (2008).

Huang, S. H. et al. Insecticidal activity of pogostone against Spodoptera litura and Spodoptera exigua (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Pest Manag. Sci. 70, 510–516 (2014).

Gordy, J. W., Leonard, B. R., Blouin, D., Davis, J. A. & Stout, M. J. Comparative effectiveness of potential elicitors of plant resistance against Spodoptera frugiperda (JE Smith) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) in four crop plants. PloS One. 10, e0136689 (2015).

Khedr, M. A., Al-Shannaf, H. M., Mead, H. M. & Shaker, S. A. Comparative study to determine food consumption of cotton leafworm, Spodoptera littoralis, on some cotton genotypes. J. Plant. Prot. Res. 55 (2015).

Parra, J. R. P. et al. Important pest species of the Spodoptera complex: Biology, thermal requirements and ecological zoning. J. Pest Sci. 1–18 (2022).

Ahmed, K. S., Mikhail, W. Z., Sobhy, H. M., Radwan, E. M. M. & Salaheldin, T. A. Impact of nanosilver-profenofos on cotton leafworm, Spodoptera littoralis (Boisd.) larvae. Bull. Natl. Res. Centre. 43, 1–9 (2019).

Aز, M. Effect of host plants on biology of Spodoptera Littoralis (Boisd). Egypt. Acad. J. Biol. Sci. Entomol. 12, 65–73 (2019).

Hosny, M., Topper, C., Moawad, G. & El-Saadany, G. Economic damage thresholds of Spodoptera Littoralis (Boisd.)(Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) on cotton in Egypt. Crop Prot. 5, 100–104 (1986).

Elbarky, N. M., Dahi, H. F. & El-Sayed, Y. A. Toxicicological evaluation and biochemical impacts for radient as a new generation of spinosyn on Spodoptera Littoralis (Boisd.) Larvae. Egypt. Acad. J. Biol. Sci. Entomol. 1, 85–97 (2008).

El-Sheikh, E., El-Saleh, M., Aioub, A. & Desuky, W. Toxic effects of neonicotinoid insecticides on a field strain of cotton leafworm, Spodoptera littoralis. Asian J. Biol. Sci. 11, 179–185 (2018).

Garrido-Jurado, I., Montes-Moreno, D., Sanz-Barrionuevo, P. & Quesada-Moraga, E. Delving into the causes and effects of entomopathogenic endophytic Metarhizium brunneum foliar application-related mortality in Spodoptera littoralis larvae. Insects 11, 429 (2020).

Ali, G., van der Werf, W. & Vlak, J. M. Biological and genetic characterization of a Pakistani isolate of Spodoptera litura Nucleopolyhedrovirus. Biocontrol Sci. Technol. 28, 20–33 (2018).

Senanayake, N. & Jeyaratnam, J. Toxic polyneuropathy due to gingili oil contaminated with tri-cresyl phosphate affecting adolescent girls in Sri Lanka. Lancet 317, 88–89 (1981).

Forget, G., Goodman, T. & De Villiers, A. Impact of Pesticide Use on Health in Developing Countries: Proceedings of a Symposium Held in Ottawa, Canada, 17–20 Sept. 1990. (IDRC, 1993).

Kole, R., Banerjee, H. & Bhattacharyya, A. monitoring of market fish samples for endosulfan and hexachlorocyclohexane residues in and around Calcutta. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 6, 554–559 (2001).

Folmar, L. C., Sanders, H. & Julin, A. Toxicity of the herbicide glyphosate and several of its formulations to fish and aquatic invertebrates. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 8, 269–278 (1979).

Shafiei, T. & Costa, H. The susceptibility and resistance of fry and fingerlings of Oreochromis mossambicus Peters to some pesticides commonly used in Sri Lanka. J. Appl. Ichthyol. 6, 73–80 (1990).

Nyirenda, S. P. et al. Farmers’ ethno-ecological knowledge of vegetable pests and pesticidal plant use in Malawi and Zambia. Afr. J. Agric. Res. 6, 1525–1537 (2011).

Amoabeng, B. W., Gurr, G. M., Gitau, C. W. & Stevenson, P. C. Cost: benefit analysis of botanical insecticide use in cabbage: implications for smallholder farmers in developing countries. Crop Prot. 57, 71–76 (2014).

Ware, G. (WH Freeman and Company, 1983).

Thacker, J. R. An Introduction to Arthropod Pest Control (Cambridge University Press, 2002).

Isman, M. B. Botanical insecticides, deterrents, and repellents in modern agriculture and an increasingly regulated world. Ann. Rev. Entomol. 51, 45–66 (2006).

Jain, S., Vaidya, A., Jain, N., Kumar, V. & Modi, A. Bioactive compounds of Royal Poinciana (Delonix regia (hook.) Raf). Bioact. Compd. Underutiliz. Veg. Legumes. 483–502 (2021).

Tura, A. M., Belay, H. & Merga, H. Physiochemical characterization and evaluation of insecticidal activities of Delonix regia seed oil against termite (odontotermes obesus), ticks (Ixodes scapularis) and cockroach (Blattella germanica). J. Nat. Sci. Res. 5, 40–46 (2015).

Sangavi, R. & Edward, Y. Anti-insect activities of plant extracts on the diamondback moth, Plutella xylostella (L). Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 6, 28–39 (2017).

Obembe, T. A., Adebowale, A. S. & Odebunmi, K. O. Perceived confidence to use female condoms among students in Tertiary Institutions of a Metropolitan City, Southwestern, Nigeria. BMC Res. Notes. 10, 1–9 (2017).

Sudhapriya, A. & Dhivya, R. Phytochemical screening and Larvicidal Efficacy of Solvent extracts of Delonix regia Leaf and Flower against Vector Mosquito Culex quinquefasciatus. Int. J. Res. Rev. 6, 206–214 (2019).

Gómez-Tah, J., Ruz-Febles, N., Campos-Navarrete, M., Canul-Solís, J. & Castillo-Sánchez, L. Ethanolic extract of Cedrela odorata and Delonix regia for the control of Anthonomus eugenii. J. Entomol. Zool. Stud. 8, 1349–1352 (2020).

Dutra, J. A. C., de Vasconcelos Gomes, V. E., Bleicher, E., Macedo, D. X. S. & Almeida, M. M. M. Efficiency of botanical extracts against Aphis craccivora Koch (Hemiptera: Aphididae) nymphs in Vigna unguiculata (L.) Walp. EntomoBrasilis 13, e910–e910 (2020).

Salman, A., Dahi, H. F. & Bedawi, A. Susceptibility of the Egyptian cotton Leafworm, Spodoptera Littoralis (Boisd.)(Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) to Entomocidal Crystal Proteins Cry1Ac and cry 2Ab baseline responses. Egypt. Acad. J. Biol. Sci. F Toxicol. Pest Control. 13, 279–291 (2021).

Abbott, W. S. A method of computing the effectiveness of an insecticide. J. econ. Entomol. 18, 265–267 (1925).

Bradford, M. M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72, 248–254 (1976).

K Laemmli, U. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227, 680–685 (1970).

Darwesh, O. M., Moawad, H., Barakat, O. S. & El-Rahim, W. Bioremediation of textile reactive blue azo dye residues using nanobiotechnology approaches. (2015).

Finney, D. Bioassay and the practice of statistical inference. Int. Stat. Rev./Rev. Int. Stat. 1–12 (1979).

Baz, M. M. et al. Evaluation of four ornamental plant extracts as insecticidal, antimicrobial, and antioxidant against the West Nile vector, Culex pipiens (Diptera: Culicidae) and metabolomics screening for potential therapeutics. (2023).

Abdullah, M. A. Identification of the biological active compounds of two natural extracts for the control of the red palm weevil, Rhynchophorus Ferrugineus (Oliver)(Coleoptera-curculionidae). Egypt. Acad. J. Biol. Sci. Entomol. 2, 35–44 (2009).

Chockalingham, S., Manoharan, T. & Kumar, U. Ovicidal, larvicidal and pupicidal activities of an indigenous plant extract against Pericallia ricini (Arctidae: Lepidoptera). (1992).

Aina, S., Banjo, A., Lawal, O. & Jonathan, K. Efficacy of some plant extracts on Anopheles gambiae mosquito larvae. Acad. J. Entomol. 2, 31–35 (2009).

Deepa, B. & Remadevi, O. Larvicidal activity of the flowers of Delonix regia (Bojer Ex Hook.) Rafin.(Fabales: Fabaceae) against the teak defoliator, Hyblaea Puera Cramer. Curr. Biotica. 5, 237–240 (2011).

Chandrakantha, J. in Abstract of III National Symposium on Nutritional Ecology of Insects and Environment.

Narayanasamy, P. Mycoinsecticide: A Novel Biopesticide in Indian Scenario. (1995).

Shanmukha, I., Patel, H., Patel, H. P. J. & Riyazunnisa, R. J. P. Quantification of Total Phenol and Flavonoid Content of Delonix Regia Flowers. (2011).

Singh, S., Luse, R., Leuschner, K. & Nangju, D. Groundnut oil treatment for the control of Callosobruchus maculatus (F.) during cowpea storage. J. Stored Prod. Res. 14, 77–80 (1978).

Adedire, C. Biology, economy and control of insect pests of stored cereal grains. In (Ofuya, T.I., Lale, N.E.S. Eds.) Pest of Nigeria. Biology, Ecology and Control. 55–94 (Dave Collins Publication, 2001).

Hoasamani, K. M. & Hosamani, S. K. Component fatty acids of Delonix regis seed oil — a source of 7-(2-Octacyclopropen-1-yI)heptanoic acid and 8-(2-OctacycIopropen-1-yl)octanoic acid. Lipid / Fett. 97, 420–422. https://doi.org/10.1002/lipi.2700971106 (1995).

Moustafa, H. Z., Yousef, H. & El-Lakwah, S. F. Toxicological and biochemical activities of fatty acids against Earias insulana (Boisd.)( Lepidoptera : Noctuidae). Egypt. J. Agric. Res. 96, 503–515. https://doi.org/10.21608/ejar.2018.135241 (2018).

Schmidt, S., Tomasi, C., Pasqualini, E. & Ioriatti, C. The biological efficacy of pear ester on the activity of Granulosis virus for codling moth. J. Pest Sci. 81, 29–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10340-007-0181-x (2008).

Silva Vde, C., Ribeiro Neto, J. A., Alves, S. N. & Lima, L. A. Larvicidal activity of oils, fatty acids, and methyl esters from ripe and unripe fruit of Solanum lycocarpum (Solanaceae) against the vector Culex quinquefasciatus (Diptera: Culicidae). Rev. Soc. Bras. Med. Trop. 48, 610–613. https://doi.org/10.1590/0037-8682-0049-2015 (2015).

Giner, M., Avilla, J., Balcells, M., Caccia, S. & Smagghe, G. Toxicity of allyl esters in insect cell lines and in Spodoptera littoralis larvae. Arch. Insect Biochem. Physiol. 79, 18–30. https://doi.org/10.1002/arch.21002 (2012).

Yousef, H., El-Lakwah, S. F. & El Sayed, Y. A. Insecticidal activity of linoleic acid against Spodoptera littoralis (Boisd.). Egypt. J. Agric. Res. 91, 573–580. https://doi.org/10.21608/ejar.2013.163516 (2013).

Gade, S. et al. Acetylcholinesterase inhibitory activity of stigmasterol & hexacosanol is responsible for larvicidal and repellent properties of Chromolaena odorata. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj. 1861, 541–550. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbagen.2016.11.044 (2017).

Jung Ji, Y., Lee Hyung, C. & Yang, J. K. Insecticidal Activity of Coptis chinensis extract against Myzus persicae (Sulzer). 목재공학 43, 274–285 (2015). https://doi.org/10.5658/WOOD.2015.43.2.274

Duke, J. Handbook of Medicinal Herbs (CRC, 1985).

Sharma, S. & Arora, S. Phytochemicals and pharmaceutical potential of Delonix regia (bojer ex hook) Raf a review. Int. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 7, 21–33 (2015).

Acheuk, F., Abdellaoui, K., Bendifallah, L., Hammichi, A. & Semmar, E. In AFPP Tenth International Conference on Pests in Agriculture Montpellier.

Benahmed Djilali, A. et al. Bioactive substances of Cydonia oblonga Fruit: Insecticidal Effect of tannins on Tribuliumm confusum. Int. J. Fruit Sci. 21, 721–731. https://doi.org/10.1080/15538362.2021.1926395 (2021).

Azab, S., Abdel-Daim, M. & Eldahshan, O. Phytochemical, cytotoxic, hepatoprotective and antioxidant properties of Delonix regia leaves extract. Med. Chem. Res. 22, 4269–4277 (2013).

Simmonds, M. S. & Stevenson, P. C. Effects of isoflavonoids from Cicer on larvae of Heliocoverpa armigera. J. Chem. Ecol. 27, 965–977. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1010339104206 (2001).

Gould, K. S. & Lister, C. Flavonoid functions in plants. In Flavonoids: Chemistry, Biochemistry,and Applications. (2006).

Diwan, R. K. & Saxena, R. C. Insecticidal property of flavinoid isolated from Tephrosia Purpuria. Int. J. Chem. Sci. 8, 777–782 (2010).

Khan, H., Amin, S., Kamal, M. A. & Patel, S. Flavonoids as acetylcholinesterase inhibitors: Current therapeutic standing and future prospects. Biomed. Pharmacother. 101, 860–870 (2018).

Talukder, F. A., Talukder, F. A. Plant products as potential stored -product insect stored management agents-A mini review. Emirates J. Food Agric. 18, 17–32. https://doi.org/10.9755/ejfa.v12i1.5221 (2017).

Rajashekar, Y., Bakthavatsalam, N. & Shivanandappa, T. Botanicals as Grain protectants. Psyche: J. Entomol. 2012, 1–13 (2012).

Twaij, B. M. & Hasan, M. N. Bioactive secondary metabolites from plant sources: Types, synthesis, and their therapeutic uses. Int. J. Plant. Biol. (2022).

Gogna, N., Hamid, N. & Dorai, K. Metabolomic profiling of the phytomedicinal constituents of Carica papaya L. leaves and seeds by 1H NMR spectroscopy and multivariate statistical analysis. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 115, 74–85 (2015).

Karunaratne, U. K. P. R. & Karunaratne, M. M. S. C. Evaluation of methanol, ethanol and acetone extracts of four plant species as repellents against Callosobruchus maculatus (Fab). Vidyodaya J. Sci. 17 (2015).

Park, I. K. Larvicidal activity of constituents identified in Piper nigrum L. Fruit against the Diamondback moth, Plutella Xylostella. Korean J. Appl. Entomol. 51, 149–152 (2012).

Hierro, N. D., Cantero-Bahillo, J., Fornari, E. & Martín, D. T. Effect of Defatting and Extraction Solvent on the Antioxidant and Pancreatic Lipase Inhibitory Activities of Extracts from Hermetia illucens and Tenebrio molitor. Insects 12 (2021).

Alves, D. M. T. et al. Identification of four novel members of Kunitz-like α-amylase inhibitors family from Delonix regia with activity toward Coleopteran insects. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 95, 166–172 (2009).

Da Lage, J. L. The amylases of insects. Int. J. Insect Sci. 10 (2018).

Eriani, K. et al. Antidiabetic potential of methanol extract of flamboyant (Delonix regia) flowers. Biosaintifika: J. Biology Biology Educ. 13, 185–194 (2021).

Babu, S. et al. Chemical compositions, antifeedant and larvicidal activity of Pongamia pinnata (L.) against polyphagous field pest, Spodoptera litura. Int. J. Zool. Invest. 2, 48–57 (2016).

Singh, R., Upadhyay, S. K., Rani, A., Kumar, P. & Kumar, A. Ethanobotanical study of Subhartipuram, Meerut, Uttar Pradesh, India. II. Diversity and pharmacological significance of shrubs and climbers. Int. J. Pharm. Res. 12, 383–393 (2020).

Bakar, K., Mohamad, H., Tan, H. S. & Latip, J. Sterols compositions, antibacterial, and antifouling properties from two Malaysian seaweeds: Dictyota dichotoma and Sargassum Granuliferum. J. Appl. Pharm. Sci. 9, 047–053 (2019).

Erharuyi, O. et al. Identification of compounds and insecticidal activity of the root of pride of Barbados (Caesalpinia Pulcherrima L). J. Appl. Sci. Environ. Manage. 21, 281–287 (2017).

Gade, S. et al. Acetylcholinesterase inhibitory activity of stigmasterol & hexacosanol is responsible for larvicidal and repellent properties of Chromolaena odorata. Biochim. et Biophys. Acta (BBA)-General Subj. 1861, 541–550 (2017).

Malami, I. Prenylated benzoic acid derivatives from Piper species as source of anti-infective agents. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Res. 3, 1554–1559 (2012).

Chauhan, N. et al. Insecticidal activity of Jatropha curcas extracts against housefly, Musca domestica. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 22, 14793–14800 (2015).

Abdel-Fatah, R. M., Mohamed, S. M., Aly, A. A. & Sabry, A. K. H. Biochemical characterization of spiromesifen and spirotetramat as lipid synthesis inhibitors on cotton leaf worm, Spodoptera littoralis. Bull. Natl. Res. Centre. 43, 1–6 (2019).

Chaniad, P. et al. In vivo assessment of the antimalarial activity and acute oral toxicity of an ethanolic seed extract of Spondias pinnata (lf) Kurz. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 22, 72 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Dr. Wael Mahmoud Kamel, Department of Biochemistry, National Research Centre, Giza, Egypt for analyzing the Native-PAGE, Miss. Aya Attia, Department of Applied Entomology & Zoology, FA, Alexandria University, Egypt for providing the insect colonies, and to the Department of Applied Entomology and Zoology, Faculty of Agriculture (El-Shatby), Alexandria University for the continuous encouragement. The authors are also thankful to the Department of Zoology & Entomology, Faculty of Science, Al–Azhar University, Cairo, Egypt for their connection and contacts.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, investigation, data curation, formal analysis, resources, writing-original draft preparation, R.S.A., M.E.G., J.Z., H.S., A.S., H.S.G., M.H.A., M.M.B.; editing and writing-review, R.S.A., M.E.G., J.Z., H.S., A.S., H.S.G., M.H.A., M.M.B.; project administration, A.S.; funding achievement, R.S.A., M.E.G., J.Z., H.S., A.S., H.S.G., M.H.A., M.M.B.; R.S.A., M.E.G., J.Z., H.S., A.S., H.S.G., M.H.A., M.M.B. All authors have read and approved the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical statement

The Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Agriculture, Alexandria University approved the work protocol (Code: Alex.Agri.112310305). We conducted the study in accordance with local legislation and institutional requirements.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ammar, R.S., Gad, M.E., Zeb, J. et al. Insecticidal activity of Delonix regia (Fabaceae) against the cotton leafworm, Spodoptera littoralis (Bois) with reference to its phytochemical composition. Sci Rep 15, 6286 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88547-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88547-7