Abstract

This study aims to investigate the nonlinear optical (NLO) characteristics of diluted crude oil samples from the Ramshir, Rag-e-Sefid, and Ahwaz-20 reservoir fields in the southwest region of Iran. Utilizing spatial self-phase modulation (SSPM) techniques, we measured the nonlinear refractive index (\({n}_{2,th}\)) by observing the intensity-dependent number of diffraction rings with continuous-wave laser beams at \(405 \text{nm}\) and \(532\text{ nm}\) wavelengths. This study focused on examining the \({n}_{2,th}/\alpha\) ratios of different sample concentrations to identify the role of thermal effects in the observed NLO responses. Our findings indicate a direct correlation between the concentration of crude oil in the samples and their NLO properties, with thermal effects significantly influencing the changes in NLO responses. In the thermal region, the nonlinear refractive index was approximately determined to be \({10}^{-5} {\text{cm}}^{2}/\text{W}\). Additionally, the study explores the collapse of diffraction rings to further understand how the relative nonlinear refractive index varies with the sample concentration and incident intensity at both wavelengths. The results suggest that crude oil possesses promising NLO properties, making it potentially suitable for the development of new photonic devices and applications, especially in areas where thermal nonlinearities are crucial, such as sensing and all-optical technologies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The nonlinear optical (NLO) properties of different materials have been extensively investigated since the invention of lasers owing to the high external electric fields provided by intense beams. Consequently, the search for materials with high NLO properties for many optical devices and telecommunication applications has intensified. Several common techniques, including four-wave mixing1,2, Z-scan3,4, and spatial self-phase modulation SSPM5,6, have been used to measure and study the NLO coefficients and properties. The Z-scan method, as it is known, requires relatively complicated optical alignment in both open-aperture and close-aperture configurations. In this method, the nonlinear absorption coefficient and refractive index of nonlinear materials are determined by measuring the amount of light passing through samples7,8. The four-wave mixing technique estimates the third-order nonlinear features of the materials interacting with four distinct wavelengths of light. In this method, the incident light changes the refractive index of the nonlinear material, resulting in a phase shift in the light and, consequently, light waves with different frequencies2.

The SSPM is a phenomenon induced by the propagation of an intense Gaussian laser beam in a nonlinear medium. This method is simple and accurate for investigating the nonlinear responses in nonlinear media9. The SSPM effect occurs when an intense Gaussian light beam interacts with an NLO medium, causing a phase change in the laser beam and resulting in a ring-shaped diffraction pattern10,11. Callen et al. were the first to observe the first self-phase modulation (SPM) phenomenon when concentric rings are formed owing to thermal effects as a light beam passes through an absorbing medium12. Stolen et al. used this effect to estimate the nonlinear coefficient of a nonlinear medium’s nonlinear coefficient13. In 1981, Durbin et al. observed the SSPM effect using a continuous-wave argon ion laser focused on a nematic liquid crystal film. Since then, researchers have observed this effect in various nonlinear media and have used it to characterize various materials14. This phenomenon is well known for investigating the NLO responses of materials. This is considered a low-cost and straightforward method for estimating the nonlinear refractive coefficients of various NLO materials15. Applications, such as optical switching and modulation, have been widely utilized in this method16,17,18. In addition, the SSPM technique has been employed as a novel method to estimate the authenticity of edible oils15,19.

Researchers have investigated the properties of crude oil by using various analytical methods combined with spectroscopic techniques. For instance, researchers have recorded the fractionation and characterization of crude oils using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) and physicochemical methods such as Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopy, vapor pressure osmometry (VPO), differential scanning calorimetry (DSC), and thermogravimetric analysis (TGA)20. The infrared fingerprints of crude oil were consistent with the GC results. Therefore, researchers have proposed substitutes for traditional petroleum geochemical methods to characterize crude oil21,22. Apart from various laser-based spectroscopic methods, such as laser-induced time-resolved fluorescence spectroscopy and laser-induced breakdown spectroscopy23,24,25, researchers have dedicated themselves to optical characterization to comprehend the properties and behavior of crude oil under varying conditions. The temperature significantly influences the optical properties of crude oil, including its refractive index, absorption index, absorption coefficient, and reflectivity26. SPR testing of crude oil reveals the differences between different oils based on their refractive indices, and it has also been shown to be a quick and nonintrusive testing method that can be used at many stages of oil processing27. Using UV–visible spectroscopy, dynamic light scattering, and microscopy to study crude oils and their asphaltene fractions helps us to understand how stable and clumpy crude oils are, which is important for understanding how to handle and transport them28. The magneto-optical activity of the crude oil and its heavy fractions showed that the presence of VO2+ complexes, which change depending on the origin of the oil, has a significant effect on the magneto-optical properties. This offers a distinct method for determining the composition of crude oil29.

Additionally, researchers have combined holographic interferometry with coherent fringe projection and laser-induced fluorescence for the remote sensing and characterization of oil films and emulsions. This technique enables the real-time monitoring and analysis of oil spills, thereby providing valuable data for environmental protection30. Characterization of the NLO behavior of crude oil has received less attention than most of the other physical features mentioned above. In 2014, Rad used a continuous wave (CW) diode laser at 660 nm to estimate the negative nonlinear refractive index \({n}_{2}\) of crude oil using the single-beam z-scan technique31. Recently, the linear and NLO properties of two types of Iraqi heavy crude oil were investigated using a He–Ne laser at \(632.8 nm\) 22 and a similar Z-scan experimental technique. To the best of our knowledge, SSPM has not yet been used to characterize the NLO properties of crude oils.

In this study, the SSPM was used to investigate the NLO response of crude oils in the thermal regime. We measured the nonlinear refractive index (\({n}_{2,th}\)), nonlinear refractive index-to-absorption coefficient ratio (\({n}_{2,th}/\alpha\)), and thermo-optics coefficient values (\(\frac{dn}{dT}\)) for various crude oil samples from southwest Iran at wavelengths of \(405 \text{nm}\) and \(532 \text{nm}\). To investigate the correlation between changes in incident intensity and relative nonlinear refractive index variations, we also analyzed the apparent "collapse effect of diffraction rings."

Materials and method

Sample preparation

Three pure crude oil samples were collected from the Ramshir, Rag-e-Sefid, and Ahwaz-20 oil reservoir fields in the Dezful Embayment area of southwest Iran. Detailed information on the specifications and compositions of the three crude oil samples is presented in Table 1. The samples were characterized based on their API gravity, specific gravity, and Saturated, Aromatic, Resin, and Asphaltene (SARA) composition expressed as weight percentages. Ramshir, with the highest API gravity (34.96) and lowest specific gravity (0.8501), is the lightest crude oil, characterized by high saturated hydrocarbon content (51.7%), low asphaltenes (3.4%), and the highest resin content (11.4%). Ahwaz-20 is the heaviest crude oil with the lowest API gravity (23.11) and highest specific gravity (0.9152) compared to other oils, and has the highest asphaltene content (9.08%) and aromatic content (37.52%). Also, Rag-e-Sefid, with intermediate API gravity (27.26) and specific gravity (0.8913), had the highest saturated hydrocarbon content (55.74%) and balanced aromatic (30.8%) and resin (9.6%) contents. It is important to note that the specific gravity (\(SG\)) for each compound in this study was computed as \(SG=141.4/(API Gravity+131.5)\)24.

Owing to their high opacity in the visible wavelength range, we were unable to directly collect samples of pure, dark, or black crude oil. To address this problem, we prepared three liquid sample solutions by diluting crude oil in toluene (\(99.9\%\) purity, Merck GmbH) with a dilution of \(0.25\text{ mL}/\text{L}\), \(0.5\text{ mL}/\text{L}\), and \(1\text{ mL}/\text{L}\), respectively. Toluene was used as a diluent because of its excellent ability to dissolve the structure of crude oil samples, which is a strong solvent for hydrocarbons and complex organic compounds. Utilizing the UV–visible spectra of both pure toluene and the prepared samples, which were measured using a \(10 \text{mm}\) optical path cuvette cell (Phystec UVS-2500), enabled us to calculate the linear absorption coefficient (\({\alpha }_{0}\)) at varying concentrations. As discussed, samples with a higher linear absorption coefficient absorb more light at laser wavelengths, causing a more significant thermal effect on the medium and exposing changes in the nonlinear refractive index of the medium. As shown in Fig. 1, pure toluene exhibited negligible spectral absorption in the \(300-800 \text{nm}\) region, indicating the unbiasedness of NLO phenomena produced by thermal effects. Accordingly, we ensured that any observed NLO effects were completely attributable to the crude oil. As can also be seen in Fig. 1, the recorded spectra of the prepared samples (i.e., mixtures of crude oil and toluene solvent at different concentrations) showed wide absorption features in the visible wavelength range, particularly at the wavelengths of the incident laser light used in our experiment. The addition of crude oil to the solvent significantly increased the absorption capacity. This led to further heating of the samples as a result of the interaction with the laser beam, which subsequently affected the SSPM results.

Spatial self-phase modulation SSPM

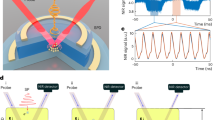

The NLO behavior of crude oil in toluene was studied using SSPM. The experimental setup is shown in Fig. 2. The SSPM effect depends on several parameters such as molecular reorientation, third-order susceptibility effects, and thermo-optical effects. It has been claimed that the change from \({n}_{2}\) to \({\chi }^{(3)}\) is valid when SSPM results from the optical Kerr effect. This has been experimentally studied by Wang et al.32. On the other hand, in the case where the SSPM is due to the thermal blooming model, as in33,34,35, the medium becomes heated, and thermal effects are localized because of high-intensity laser radiation.

Thermal iens model

Gordon et al.36 reported the first observation of thermal lensing. This phenomenon occurs when a Gaussian beam traverses the absorption medium. Because the medium absorbs a portion of the beam energy, it generates a temperature distribution that corresponds to the radial profile of the beam. Therefore, the variation in medium density caused by this temperature gradient leads to a gradient in the refractive index37,38,39. Thermal lenses generally exhibit a parabolic refractive-index distribution, which is evidence of negative lens characteristics39. The refractive-index distribution is mathematically described as in40. A substantial nonlinear change in the refractive index occurs in materials with high thermo-optical coefficients, as reported in Ref.41,42. The refractive index distribution induced by the temperature variation can be calculated as42:

The change in the refractive index is expressed by:

The refractive index as a function of temperature is represented by \(n(r,t)\). The parameters used are as follows: \(r\) is the radial coordinate, \({n}_{0}\) is the linear refractive index of the medium, \(\partial n/\partial T\) is the thermo-optic coefficient, and \(\Delta T(r,t)\) represents the temperature variation. The thermo-optic coefficient of the liquid was negative because of the thermal effect of the laser. This effect reduces the local density, which leads to a decrease in the refractive index43. The Soret effect is represented by \(\partial n/\partial c \Delta c(r,t)\) in Eq. (2). Because of this effect, local variations in concentration \(c\) result in a change in the refractive index. The Soret effect occurs when a temperature gradient causes thermal diffusion and movement of molecules in the temperature gradient44. It was determined that the Soret effect can be neglected when using the toluene parameter values at room temperature, as detailed in Ref.42. Hence, Eq. (2) can be simplified as

The temperature distribution resulting from the propagation of the beam in the sample, \(\Delta T(r,t)\), can be approximated using the Green function for heat conduction and convection equations, as described in Refs.33,34.

The vertical convection velocity, represented by \({v}_{y}\), reaches its maximum value at radius \({\omega }_{0}\) of the propagating beam at the center. In Eq. (4), \(t\) is the absorption time, and the thermal diffusivity, denoted by \(D\), is defined as the ratio of the thermal conductivity (\(K\)) to the product of the density (\(\rho\)) and specific heat capacity (\(c\)). In addition, \(P\) represents the laser power. The expression for the nonlinear phase shift of a Gaussian beam as it passes through a liquid sample was presented by33,35,42:

where \(\lambda\) is the laser wavelength,\(\delta = ((\partial n/\partial T)\alpha PL\_e)/\uplambda K\) is the on-axis phase shift, and \({t}_{c}={{\omega }_{0}}^{2}/4D\) The value of \({L}_{e}\) can be determined by \({L}_{e}=\left(\left(1-{e}^{\left(-\alpha L\right)}\right)\right)/\alpha\), under the assumption that the beam is reasonably collimated and maintains a nearly constant transverse area within the sample with a length of \(L\). The number \(N\) of the far-field diffraction pattern of SSPM rings depends on the phase shift and position of the sample relative to the beam waist, as well as the nonlocality of the nonlinearity32. Furthermore, we can estimate the incident intensity of the laser beam as \(I=\left(2{P}_{average}\right)/\left(\left(\pi {\omega }^{2}\right)\right)\), where \(\omega\) represents the measured beam radius at the cuvette entrance. When the cuvette length (\(L\)) was smaller than the estimated Rayleigh length (\(2{Z}_{R}\)), and the sample was placed in front of the laser within the Rayleigh range, the beam spot remained approximately constant and equal to the beam radius at the focal point \({\omega }_{0}\). Therefore, the induced thermal nonlinear refractive index as a function of the number of diffraction rings can be expressed as19,41,45:

Furthermore, for thermal nonlinearity, the change in the on-axis nonlinear index can be expressed by45,46:

Ring Collapse effect

The intensity profile of a laser beam at the output detector plane can be determined using the Fraunhofer approximation of the Fresnel-Kirchhoff diffraction integral and complex amplitude of the laser field at the output plane of the sample. This is given by33,34:

Here, \(x{\prime}\) and \(y{\prime}\) are the spatial variables in the detector plane, and \(d\) is the distance between the detector plane and exit plane of the sample.

Equation (8) predicts that the asymmetry of the temperature distribution caused by the vertical convection velocity leads to the asymmetrical shape of the diffraction patterns in the observed SSPM rings. When \({v}_{x}\) has a non-zero value, the SSPM diffraction patterns change from symmetric to asymmetrical forms (D-form), and the diffraction rings quickly collapse after formation, which is known as the "Collapse Effect of Diffraction Rings." With a constant incident intensity of the continuous laser, the convection velocity stabilizes after a period of time, resulting in the observed stable D-form diffraction patterns after a short period of laser irradiation33,34.

Several nonlinear materials have already exhibited the collapse effect of Diffraction Rings28,29,30,31. This phenomenon is more significant because of the relatively large thermal effects and can be explained by gravity as well as the effect of non-axisymmetric thermal convection (hydrodynamic processes)5,6,23. Analyzing the apparent distortion in the diffraction rings enables the study of the correlation between changes in the incident intensity and the relative nonlinear refractive index variations.

Figure 3 shows a schematic and experimental diagram of the SSPM ring deformation of the diffraction rings captured by a CCD camera. The maximum half-diffraction angle and radius before the collapse are denoted by \({R}_{H}\) and \({\theta }_{H}\), respectively. After the collapse of the diffraction rings, these values become \({R}_{H}^{,}\) and \({\theta }_{H}^{,}\). The collapse angle and distance are defined as \({\theta }_{D}\) and \({R}_{D}\), respectively.

Equation (9) can be used to investigate changes in the nonlinear refractive index by identifying the maximum half-diffraction angle (\({\theta }_{H}\)) and collapse angle (\({\theta }_{D}\))32,35,47:

Results and discussion

Figure 4 shows the diffraction ring patterns obtained for each sample, including Ramshir, Rag-e-Sefid, and Ahwaz-20 crude oil in toluene at the highest prepared concentrations, using laser beams with \(405 nm\) and \(532 nm\) wavelengths. The diffraction rings produced by the SSPM were due to the laser-induced changes in the local refractive index. As the fringes approached the center, their intensity and width decreased, whereas the outer rings exhibited the highest intensity and widest width. This finding implies that the laser-induced thermal lens effect has a major impact on phase modulation under an intense continuous-wave laser, resulting in the formation of the observed diffraction ring patterns. Notably, absolute toluene did not produce diffraction ring patterns when irradiated with lasers at either wavelength. This finding suggests that the NLO response was caused by the crude oil in the solution samples rather than by any other components in the mixture.

Another characteristic related to NLO behavior is the amount of light necessary to observe the first diffraction ring pattern, \(N=1\), for each sample, which can be obtained under identical experimental conditions. As shown in Fig. 5, the intensity required to observe the first diffraction ring pattern, \(N=1\), decreases as the crude oil concentration in toluene increases. It is noted that all the diffraction pattern features explained in terms of the SSPM rely on the experiment. By adjusting the sample holder thickness, lens focal length, and laser wavelength, the number of diffraction rings and threshold intensity may be different.

In our investigation, samples with higher crude oil concentrations showed larger linear absorption coefficients at both wavelengths. As a result, light absorption increases the temperature effect of such a medium, causing a greater variation in the nonlinear refractive index and more effective NLO behavior. This indicates that the intensity required to observe a certain number of rings differs for each sample. This shows that each sample exhibited a distinctive nonlinear behavior. As the laser intensity increased, a diffraction ring pattern appeared on each sample, causing new rings to emerge from the center of the pattern and increasing the number and radius of rings.

Figure 5 shows the variation in the number of rings generated by changing the intensity of the laser beam. The number of rings and the intensity have a linear relationship with the slope of \(dN/dI\). The NLO characteristics of the samples became more apparent when the slope of the fitted line, \(dN/dI\) increased. Equation (6) can be used to calculate the nonlinearity value, \({n}_{2,th}\), by calculating the \({L}_{eff}\) value and linear absorption values for each sample at a given concentration. Table 2 presents the measured nonlinear refractive indices for the various samples, which were found to be of the order of \({10}^{-5}{\text{ cm}}^{2}/\text{W }\). In addition, it is obvious that at both wavelengths used, a direct correlation exists between the light absorption of the sample and \({n}_{2,th}\) values; with increasing light absorption ability, the value of \({n}_{2,th}\) also increases. Equation (7) allowed us to estimate a thermo-optics coefficient on the order of \({10}^{-2} {^\circ{\rm C} }^{-1}\), with values typically increasing as the crude oil concentration increased. The phase shifts of the final rings were determined using Eq. (5), and are presented in Table 2. The results indicated a larger phase shift for Rag-e-Sefid at \(532 nm\) than for the other samples. In Table 3, the measured values of \({n}_{2,th}\) for the examined crude oil samples are compared with other reported values obtained from SSPM and Z-scan techniques based on thermal-induced nonlinearity. The findings indicate a significant agreement between the nonlinear refractive coefficients of crude oils and materials that have already been reported.

Figures 6a and 6b depict the varying values of the calculated nonlinear refractive index for the samples with various concentrations. The results indicated that the \({n}_{2,th}\) values for all samples increased as the concentration increased, independent of the wavelength. Nevertheless, the values of \({n}_{2,th}\) values obtained at \(405 nm\) were more significant than those obtained at \(532 nm\). These results can be attributed to the stronger absorption capacity of oil samples at the \(405 nm\) compared to \(532 nm\), which causes the \(405 nm\) laser radiation to have greater thermal effects on the samples than the \(532 nm\) laser radiation. A greater thermal effect results in more significant changes in the refractive index, which directly enhances the optical nonlinearity. Consequently, a larger nonlinear refractive index was predicted.

To investigate the thermal sources of the NLO response and the relationship between the linear absorption coefficient (\({\alpha }_{0}\)) and the SSPM results, we look at the ratio (\({n}_{2,th}/{\alpha }_{0}\)) of samples for different concentrations, which is shown on the right y-axis in Fig. 6a for \(405 nm\) and Fig. 6b for \(532 nm\). It is well known that sample absorbance varies not only based on the optical characteristics of crude oils but also by their concentration in the provided samples. The Beer-Lambert law was used to calculate \({\alpha }_{0}\) from the absorption spectra. The values for the samples at both wavelengths are listed in Table 2. Our SSPM results indicate that \({n}_{2,th}\) is correlated with the sample absorbance; that is, the higher the absorption, the higher is the thermally generated nonlinearity. The relationship between \({\alpha }_{0}\) and \({n}_{2,th}\) is evident from the analysis of the ratio \({n}_{2,th}/{\alpha }_{0}\) ratio shown in Fig. 6a and 6b. As can be observed, for wavelengths \(405 nm\) and \(532 nm\), the ratios for all materials are comparable and are mostly close for each sample at different concentrations. This demonstrates that, regardless of the composition of the crude oils, their main function is to absorb optical excitation and heat the sample, resulting in nonlinear changes in the refractive index that cause the SSPM. The nonlinear changes in the refractive index within each spectral region should follow the absorbance of the samples such that the ratio \({n}_{2,th}/{\alpha }_{0}\) was practically the same for many different concentrations. Such behavior would not be expected if the investigated SSPM effect were not predominantly thermal. On the other hand, we can compare these thermally based optical nonlinearity results with those of other reported works that investigated the nonlinear behavior of several different materials using the Z-scan technique. As Sudha and coworkers explained in their studies48,49,50, when employing the Z-scan technique with a continuous-wave laser, the light absorption of the material significantly contributes to the generation of thermal effects, ultimately leading to the observed nonlinear optical phenomena. Furthermore, these studies have reported \({n}_{2}\) values of the order of \({10}^{-7}{\text{ cm}}^{2}/\text{W }\), which are roughly comparable to the findings of this research. In addition, these values were consistent with the range of thermally induced NLO parameters anticipated for nonlinear materials51.

The diffraction ring patterns in Fig. 4 exhibit a D-form shape, which can be ascribed to the " collapse of the diffraction rings." As described in Eq. (8), this asymmetry formed in ring patterns as a result of the vertical convection velocity-induced temperature distribution, and it appeared rapidly after the laser beam radiation.

Figure 7 illustrates the simulation of the far-field diffraction patterns of a laser beam propagating through a liquid with varying convection velocities using Eq. (8) and the typical physical values of the samples. As the convection velocity increased, distinct vertical asymmetry in the diffraction ring patterns became apparent. This asymmetry indicates that convection currents significantly reduce the temperature gradient within the liquid, leading to a decrease in the refractive index gradient. Consequently, the phase modulation of the optical field is diminished, resulting in a smaller outward diffraction angle and the formation of a compressed asymmetric diffraction ring pattern.

(a-e) Far-field diffraction patterns of a laser beam propagating through a liquid with varying convection velocities (\(0 to 5 mm/s\)). (f-j) Variation of intensity along the vertical axis at the center of the ring patterns. (k–o) Variation of intensity along the horizontal axis at the center of the ring patterns.

In our experiment, we observed that when laser radiation heated the sample at the focal point of the lens, several microbubbles appeared while recording the diffraction ring patterns. Thermal convection causes bubbles to rise. This effect became more pronounced as the incident laser intensity was increased. The resulting collapsed diffraction patterns were used to determine the maximum half-diffraction angle (\({\theta }_{H}\)) and the distortion angle (\({\theta }_{D}\)). As expected, the maximum half-angle of diffraction and angle of collapse increased proportionally with the magnitude of the incident beam.

Figure 8 depicts the variations in the maximum half-diffraction angle (\({\theta }_{H}\)), distortion angle (\({\theta }_{D}\)), and estimated ratios of \({\Delta n}_{2,th}/{n}_{2, th}\) with respect to the incident light intensity at both wavelengths for samples with varying concentrations.

Variation of half-cone angle (\({\theta }_{H}\)), distortion angle (\({\theta }_{D}\)), and nonlinear refractive index for Ramshir (a, d), Rag-e-Sefid (b, e), and Ahwaz-20 (c, f) crude oil/toluene samples irradiated with \(405 nm\) and \(532 nm\) laser beams, respectively. The samples were prepared at the highest concentration of \(1 mL/L\).

It was found that the samples with higher concentrations of crude oil exhibited a more pronounced collapse effect. Consequently, when the concentration was increased, the relative change in the nonlinear refractive index became more apparent. For instance, Fig. 8a and Fig. 8d show the variations in the maximum half-diffraction angle (θH) and distortion angle (θD) as well as the relative variation in the nonlinear refractive index (\({\Delta n}_{2,th}/{n}_{2.th}\)) for samples containing a diluted solution of ramshir crude oil in toluene at a concentration of \(1mL/L\). As shown, the values of \({\Delta n}_{2,th}/{n}_{2,th}\) for this sample increased from \(25\text{\%}\) to \(60\text{\%}\) and from \(25\text{\%}\) to \(73\text{\%}\) , respectively, when the incident intensity of light at wavelengths \(405 nm\) and \(532 nm\) increased. Figure 7 shows that the relative change in the nonlinear refractive index has an upper limit. As the number of rings increases, this level becomes increasingly solid.

Ring numbers are associated with a higher incidence intensity, excitation wavelength, and concentration; therefore, we could determine this level with greater accuracy at higher incident intensities and sample concentrations. Thus, according to the "Ring collapse effect" investigation, the relative change value of the nonlinear refractive index is affected by the sample concentration, laser beam intensity, and wavelength.

Conclusion

In this study, we investigated the NLO responses of crude oil samples obtained from the oil reservoir fields of Ramshir, Rag-e-Sefid, and Ahwaz-20. By employing the spatial self-phase modulation (SSPM) technique, we established a straightforward and effective method for characterizing the thermally induced optical nonlinearity of complex fluids, including crude oils. Based on the far-field diffraction pattern, we estimated the nonlinear refractive index of the samples at \(405 nm\) and \(532 nm\) of about \({10}^{-5} {cm}^{2}/W\) which agrees with the values expected for thermal NLO refractive indices from previous research. In addition, using the deduced \({n}_{2,th}\), the values for the samples and the thermo-optic values for each sample were calculated to be of the order of \({10}^{-2} {^\circ{\rm C} }^{-1}\) and they consistently increased with higher concentrations of crude oil samples.

The results show that crude oil contaminants caused NLO reactions in the samples. Notably, the Rage-e-Sefid sample exhibited more pronounced NLO behavior at \(532 nm\), while the Ramshir sample displayed stronger NLO effects at \(405 nm\) compared to the rest. The utilization of a continuous-wave (CW) laser in this study, along with the significance of rising temperature (resulting in thermal alterations within the liquid) and absorption coefficient values, directly influences the calculation of the nonlinear refractive index and is the primary reason for the SSPM observations. Moreover, through the assessment of the collapsed ring produced by the "Collapse effect of the diffraction rings" we were able to ascertain the relative nonlinear refractive index change for each sample.

"The discovery of crude oil’s potential in NLO and materials research is a groundbreaking finding. Our study reveals that this old petrochemical product has excellent NLO properties, offering a path for creating cost-effective and high-performance optics. We believe that the insights gained from this study can pave the way for future research and exploration of the potential of crude oil to innovate optical devices and applications in photonics, particularly in sensing technologies and the realization of all-optical systems. Future research should focus on understanding the unique NLO properties of different crude oil types, refining the device-manufacturing process, and integrating these devices into practical applications. Moreover, the SSPM technique can rapidly analyze not only NLO properties but also other correlated physical and chemical properties of crude oil in its liquid phase, such as viscosity, density, and thermodynamic properties. This makes the SSPM a valuable tool for monitoring petrochemical products in real time, enabling faster and more efficient control and quality assurance.

In short, our findings challenge the conventional view of crude oil as only a fuel source and suggest its potential as a versatile resource with diverse applications in optics and materials science. We foresee a significant contribution of crude oil in advancing both optical technology and material studies in the future. Furthermore, the SSPM can quickly characterize the physical and chemical properties of crude oil in real time."

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available in this published article.

References:

Hendry, E., Hale, P. J., Moger, J., Savchenko, A. K. & Mikhailov, S. A. Coherent nonlinear optical response of graphene. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 097401 (2010).

Wang, Y., Lin, C.-Y., Nikolaenko, A., Raghunathan, V. & Potma, E. O. Four-wave mixing microscopy of nanostructures. Adv. Opt. Photon. 3, 1–52 (2011).

Chapple, P., Staromlynska, J., Hermann, J., Mckay, T. & McDuff, R. Single-beam Z-scan: measurement techniques and analysis. J. Nonlinear Optic. Phys. Mat. 6, 251–293 (1997).

Zhang, H. et al. Z-scan measurement of the nonlinear refractive index of graphene. Opt. Lett. 37, 1856–1858 (2012).

Ji, W., Chen, W., Lim, S., Lin, J. & Guo, Z. Gravitation-dependent, thermally-induced self-diffraction in carbon nanotube solutions. Opt. Express 14, 8958–8966 (2006).

Wu, R. et al. Purely coherent nonlinear optical response in solution dispersions of graphene sheets. Nano Lett. 11, 5159–5164 (2011).

Sheik-Bahae, M., Said, A. A., Wei, T.-H., Hagan, D. J. & Van Stryland, E. W. Sensitive measurement of optical nonlinearities using a single beam. IEEE J. Quantum Electron. 26, 760–769 (1990).

Yin, M., Li, H., Tang, S. & Ji, W. Determination of nonlinear absorption and refraction by single Z-scan method. Appl. Phys. B 70, 587–591 (2000).

Golestanifar, M., Haddad, M. A., Hassan, A. N. & Ostovari, F. Intensity-dependent thermally induced nonlinear optical response of graphene oxide derivative in hydraulic oil. Int. J. Opt. Photon. 17, 3–14 (2023).

Owji, E., Ostovari, F., Haddad, M. A., Golestanifar, M. & Keshavarz, A. Investigation of thermally induced nonlinear optical response of polyurethane-graphene composite by SSPM method. Opt. Mater. 157, 116044 (2024).

Ribeiro, M., Turchiello, R. & Gómez, S. Employment of laser beam self-phase modulation for detecting adulterations in light-absorbing commercial fluids. Food Anal. Methods 12, 908–913 (2019).

Callen, W., Huth, B. & Pantell, R. Optical patterns of thermally self-defocused light. Appl. Phys. Lett. 11, 103–105 (1967).

Stolen, R. & Bjorkholm, J. Parametric amplification and frequency conversion in optical fibers. IEEE J. Quantum Electron. 18, 1062–1072 (1982).

Durbin, S., Arakelian, S. & Shen, Y. Laser-induced diffraction rings from a nematic-liquid-crystal film. Opt. Lett. 6, 411–413 (1981).

Hassan, A. N., Haddad, M. A., Golestanifar, M. & Behjat, A. Non-linear optical response as a food authentication: investigation of non-linear optical properties of edible oils by spatial self-phase modulation (SSPM) method. Food Anal. Methods 16, 1392–1402 (2023).

Pan, Y., Lyu, Z. & Wang, C. All-optical switching in azo dye doped liquid crystals based on spatial cross-phase modulation. OSA Continuum 4, 2714–2720 (2021).

Wu, Y. et al. Emergence of electron coherence and two-color all-optical switching in MoS2 based on spatial self-phase modulation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 112, 11800–11805 (2015).

Hassan, A. N., Haddad, M. A., Behjat, A. & Golestanifar, M. Optical nonlinearity and all-optical switching in pumpkin seed oil based on the spatial cross-phase modulation (SXPM) technique. Sci. Rep. 14, 18158 (2024).

Hassan, A. N., Haddad, M. A., Golestanifar, M. & Behjat, A. Investigating the nonlinear optical response of virgin cherry kernel oil and its application to detecting adulteration. Phys. Scr. 99, 075507 (2024).

Castro, L. V. & Vazquez, F. Fractionation and characterization of Mexican crude oils. Energy Fuels 23, 1603–1609 (2009).

Asemani, M. & Rabbani, A. R. Detailed FTIR spectroscopy characterization of crude oil extracted asphaltenes: Curve resolve of overlapping bands. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 185, 106618 (2020).

Mahmood, A. I., Fandi, S. K. & Naser, H. A. Comparative study of the linear and nonlinear optical properties for different Iraqi heavy and light crude oils. Iraqi J. Phys. 18, 11–20 (2020).

Bol’shakov, A. A., Pandey, S. J., Mao, X. & Liu, C. Analysis of liquid petroleum using a laser-induced breakdown spectroscopy instrument. Spectrochim. Acta, Part B 179, 106094 (2021).

El-Hussein, A., Marzouk, A. & Harith, M. Discriminating crude oil grades using laser-induced breakdown spectroscopy. Spectrochim. Acta, Part B 113, 93–99 (2015).

Izan, R., Haddad, M. A. & Borhani Zarandi, M. Elemental analysis of asphaltene precipitation in southwestern oil wells of Iran using the laser-induced breakdown spectroscopy. J. Petroleum Res. 34, 140–149 (2024).

Zhou, W. et al. Optical properties of crude oil with different temperatures. Optik 196, 162946 (2019).

Ooms, M. D., Fadaei, H. & Sinton, D. Surface plasmon resonance for crude oil characterization. Energy Fuels 29, 3019–3023 (2015).

Cruz, E. E. B., Rivas, N. V. G., García, U. P., Martinez, A. M. M. & Banda, J. A. M. Characterization of crude oils and the precipitated asphaltenes fraction using UV spectroscopy, dynamic light scattering and microscopy in Recent Insights in Petroleum Science and Engineering (ed. Mansoor Zoveidavianpoor) 117–135 (IntechOpen, 2018).

Sokolov, A. et al. Magneto-optical activity of crude oil and its heavy fractions. Opt. Spectrosc. 112, 755–762 (2012).

Chirita, A., Kukhtarev, N., Kukhtareva, T. & Gallegos, S. Remote sensing and characterization of oil on water using coherent fringe projection and holographic in-line interferometry. Opt. Eng. 52, 035601–035601 (2013).

Rad, A. G. Single beam Z-scan measurement of nonlinear refractive index of crude oils. J. Modern Phys. 5, 44386 (2014).

Wang, Y. et al. Distinguishing thermal lens effect from electronic third-order nonlinear self-phase modulation in liquid suspensions of 2D nanomaterials. Nanoscale 9, 3547–3554 (2017).

Karimzadeh, R. Spatial self-phase modulation of a laser beam propagating through liquids with self-induced natural convection flow. J. Opt. 14, 095701 (2012).

Karimzadeh, R. Studies of spatial self-phase modulation of the laser beam passing through the liquids. Opt. Commun. 286, 329–333 (2013).

Liao, Y., Song, C., Xiang, Y. & Dai, X. Recent advances in spatial self-phase modulation with 2D materials and its applications. Ann. der Physik 532, 2000322 (2020).

Gordon, J., Leite, R., Moore, R., Porto, S. & Whinnery, J. Long-transient effects in lasers with inserted liquid samples. J. Appl. Phys. 36, 3–8 (1965).

Jalali, A. A., Rybarsyk, J. & Rogers, E. Thermal lensing analysis of TGG and its effect on beam quality. Opt. Express 21, 13741–13747 (2013).

Pu, S. et al. Suppressing the thermal lens effect by magnetic-field-induced mass transfer and phase separation in a magnetic fluid. Appl. Phys. Letters 87, 021905 (2005).

Whinnery, J. R. Laser measurement of optical absorption in liquids. Acc. Chem. Res. 7, 225–231 (1974).

Li, C. Nonlinear optics: principles and applications (ed. Chunfei Li) (Springer, 2017).

Bautista, J. E. et al. Intensity-dependent thermally induced nonlinear optical response of two-dimensional layered transition-metal dichalcogenides in suspension. ACS Photon. 10, 484–492 (2023).

Dengler, S., Azarian, A. & Eberle, B. New insights into nonlinear optical effects in fullerene solutions—A detailed analysis of self-diffraction of continuous wave laser radiation. Mat. Res. Express 8, 085702 (2021).

Ghosh, G. Handbook of optical constants of solids. In Handbook of thermo-optic coefficients of optical materials with applications (ed. Palik, E. D.) (Academic Press, 1998).

Shen, J., Lowe, R. D. & Snook, R. D. A model for cw laser induced mode-mismatched dual-beam thermal lens spectrometry. Chem. Phys. 165, 385–396 (1992).

Zidan, M., Al-Ktaifani, M., El-Daher, M., Allahham, A. & Ghanem, A. Diffraction ring patterns and nonlinear measurements of the Tris (2′, 2-bipyridyl) iron (II) tetrafluoroborate. Opt. laser Technol. 131, 106449 (2020).

Ogusu, K., Kohtani, Y. & Shao, H. Laser-Induced Diffraction Rings from an Absorbing Solution. Opt. Rev. 3, 232–234 (1996).

Jia, Y. et al. Nonlinear optical response, all optical switching, and all optical information conversion in NbSe 2 nanosheets based on spatial self-phase modulation. Nanoscale 11, 4515–4522 (2019).

Sudha, N., Surendran, R. & Jeyaram, S. Synthesis, spectral, solvent dependent linear and nonlinear optical characteristics of (E)-N-(3-(3-(4(dimethylamino)phenyl)acryloyl) phenyl)quinolone-2-carboxamide. J. Fluoresc. 32, 1471–1480 (2022).

Sudha, N., Surendran, R. & Jeyaram, S. Low power Z–scan studies of Schiff base (E)-N’-(4-(dimethylamino) benzylidene) isonicotinohydrazide for nonlinear optical applications. Indian J. Phys. 97, 4399–4408 (2023).

Sudha, N., Surendran, R. & Jeyaram, S. Vibrational spectroscopic, structural, linear and third-order nonlinear optical properties of isoniazid-vanillin hybrid. Indian J. Phys. 98, 1453–1462 (2024).

Boyd, R. W. The intensity-dependent refractive index. In Nonlinear optics 4th edn (ed. Boyd, R. W.) 203–248 (Academic Press, 2020).

Nayak, S. K. et al. Harnessing coherent light−matter interactions for all-optical switching and logic gate applications with macrocyclic phthalocyanines. ACS Appl. Opt. Mat. 2, 453–465 (2024).

Wu, L. et al. MXene-based nonlinear optical information converter for all-optical modulator and switcher. Laser Photon. Rev. 12, 1800215 (2018).

Marbello, O., Valbuena, S. & Racedo, F. J. Non-linear optical response of edible oils by means of the Z-scan technique. J. Phys.: Conf. Ser. 1219, 012008 (2019).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their gratitude to Mrs. Roghaye Izan for her invaluable assistance in obtaining crude oil samples from the National Iranian South Oil Company. We sincerely thank the company for their cooperation in providing Ramshir, Rag-e-Sefid, and Ahwaz-20 crude oil samples from reservoir fields in Southwest Iran. Additionally, we would like to acknowledge the insightful scientific consultations provided by Prof. Sergio Leonardo Gómez from the State University of Ponta Grossa- Brazil. Their expertise and guidance were instrumental in the successful completion of this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M. G. conducted the experiment, material preparation, prepared all figures (except Fig. 6), analyzed the results, and wrote the original draft. M. A. H. supervised the project, data collection, analyzed the results, and reviewed the manuscript. A. N. H. conducted the experiment, material preparation, contributed to the investigation, and reviewed the manuscript. K. P. prepared Fig. 6, contributed to the investigation, and reviewed the manuscript. Finally, all authors contributed to the manuscript editing after discussing the results.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Golestanifar, M., Haddad, M.A., Hassan, A.N. et al. Exploring the thermal-induced optical nonlinearity of crude oil via spatial self-phase modulation technique. Sci Rep 15, 3973 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88576-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88576-2

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Effect of titanium (IV) isopropoxide fillers (Ti(OiPr)4) on structural, optical, and dielectric properties of epoxy resin composites for optoelectronic devices

Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Electronics (2026)