Abstract

With increasing demand of electric vehicles (EVs), problems such as insufficient EV charging piles and unreasonable layout of EV charging stations are also becoming prominent. New challenges are introduced to the planning of urban EV charging infrastructures. To effectively plan the charging facilities, accurately predicting EV charging loads is essential. The present study proposes a spatio-temporal distribution prediction model for EV charging loads in transportation-power coupled network (TPCN). First, path planning is performed separately using the Dijkstra algorithm and refined origin-destination (OD) probability matrix based on the travel characteristics of various vehicle types. The charging selection model is then formulated considering multiple compelling factors, such as transportation conditions, ambient temperature, rest days and so on. Furthermore, the transportation-power coupled network is established based on the graph-theoretic analysis approach, and the spatial and temporal distribution characteristics of charging loads are predicted by Monte Carlo simulation. Finally, a case study is conducted in an actual urban region. The results show that EV charging load presents significant differences in different functional areas, different time periods and scenarios, and the proposed method can accurately predict the spatial-temporal distribution of charging load. This study represents a reliable approach for predicting charging demand in a certain region, and also provides powerful support for the rational planning of EV charging stations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Due to the exacerbation of global warming, the depletion of fossil fuels, and increasing environmental pollution, countries are actively promoting the transition from fossil fuels to clean energy sources to reduce carbon emissions. The transportation sector is one of the largest contributors to greenhouse gas emissions. In recent years, the growing popularity of electric vehicles (EVs) is driven by their low energy consumption, zero emissions and other environment benefits. These advantages have contributed to the rapid development of EVs as a sustainable mode of transportation, with increasing market penetration. In 2020, global EV sales increased by 43% from the previous year, reaching a 4.6% market share of the global automotive industry. EV sales continued to grow significantly in 2021, doubling to 6.75 million units. By 2022, more than 10 million EVs were sold, accounting for 14% of all new car sales. This growth resulted in over 26 million EVs on the road globally, a 60% increase compared to 2021. Although full electrification remains a distant goal, the rapid expansion of the EV market is undeniable. However, the current planning of EV charging stations still lacks mature theoretical guidance. This has led to disorganized expansion and an imbalance in the utilization of charging infrastructure. Some charging stations remain underutilized, while others experience overload. This situation not only waste public resources but also cause significant inconvenience to the public. Besides, the transition to EVs can introduce new operational and design challenges for grid operators1. For example, random and disorganized mobile loads which can potentially affect grid stability. Uncoordinated connections of large numbers of EVs during peak load periods can lead to grid congestion, voltage fluctuations, higher network losses, and compromising grid reliability2.

The EV charging market is currently in its early stages, with uncertainties surrounding the planning of charging infrastructure and service provision3. The penetration of EVs as an emerging electrical load for distribution network has drawn attention4. Besides, the rapid growth in the penetration rate of renewable energy places higher demands on the grid’s ability to adjust flexibly. Due to their dual role as both a source and a load, along with their flexibility and mobility, EVs can participate in demand response programs to help achieve peak shaving and valley filling. This is of great significance for promoting sustainable energy development and reducing carbon emissions.Therefore, accurate prediction of the spatial and temporal distribution of EV charging loads is crucial for optimizing charging station layouts and managing urban power distribution systems. This is particularly urgent as the increasing number of EVs amplifies the complexity and unpredictability of charging load distributions5,6,7. To support the rational planning and layout of charging infrastructure, as well as to assess the impact of EV integration on the distribution grid, this research aims to develop a method for accurately predicting the spatio-temporal distribution of EV charging load demand.

Literature review

During the past decade, various researchers have proposed different prediction models for EV charging load considering EV usage behaviors, including travel, parking and charging activities8,9. One of the common approaches in existing studies involves utilizing probabilistic statistics to model the specific behavior of EVs, based on characterizing vehicle or user behavior. This includes the development of sub-models such as the EV usage pattern model, the charging choice model, and the smart charging response model10. Additionally, analyzing historical charging event data is also frequently employed to forecast EV charging demand. However, this method may not yield accurate estimates of future demand due to its limited capacity to account for evolving trends and uncertainties.

In the field of electric vehicle charging load forecasting, numerous studies have approached the problem from diverse perspectives, employing a range of methodologies and giving rise to various research trajectories. For instance11, employed truncated Gaussian distributions to model EV arrival and departure times and State of Charge (SOC), with a particular focus on the statistical characteristics of scenario simulations. In a more advanced approach12, presented a dynamic prediction model for EV charging loads under different scenarios by constructing a spatio-temporal framework that integrates the Markov decision process and Monte Carlo simulations13. conducted a Monte Carlo simulation of EV charging in a residential community, using an agent-based EV charging model (ABM) to investigate the effects of different EV penetration levels and user charging decisions on the New Zealand power grid in residential area.

Furthermore, data-driven approaches have also been widely employed in EV charging load forecasting. For example14, utilized smartphone navigation data to map the temporal and spatial patterns of EV owners’ charging activities, providing a robust foundation for future infrastructure planning. Similarly15, developed a charging load prediction framework based on stochastic user equilibrium and trip chaining, with a specific focus on modelling EV driving behavior under synchronous traffic conditions.

Cluster analysis methods have also been employed in this field5. classified EV users with different characteristics using a two-step Gaussian Mixture Model and k-means clustering approach, and subsequently predict the charging demand by simulating trip chains16. explored the spatial distribution of charging demand across different locations, employing an agent-based trip chain model (ABTCM) to analyze these distribution patterns in greater detail.

In the context of user behavior modeling17, employed a Bayesian approach to establish transfer relationships between activities and proposes a charging demand prediction framework that accounts for users’ bounded rationality. In contrast18, focused more on capturing user attitudes and preferences within individual decision-making processes, utilizing the cumulative prospect theory (CPT) framework. Additionally19, explored the influence of social characteristics on charging behavior, and investigate the evolving patterns of daily charging loads across diverse demographic and social attributes.

In addition, in order to mitigate the possible adverse impact on the power grid after large-scale EVs are connected to the grid, many studies are devoted to user-side management strategies and charging stations technology development20. developed an indirect control strategy based on price elasticity, which adjusts the charging behavior of EV users to cope with the capacity limitations of charging stations and power grids21. explored the different types of control strategies, including indirect and direct control, which have important implications for how to manage and optimize the growing EV charging demand22. presented a bidirectional energy management system that integrates a solar photovoltaic (PV) array, a battery energy storage (BES), a diesel generator (DG) set, and a grid-based electric vehicle (EV) charging station (CS) to alleviate the pressure on the grid caused by EV charging behavior. To manage the energy of EVs with uncertain charging state23, proposed a smart radial distribution network with an aggregator, power market, G-2-V, and V-2-G facility.

In conclusion, numerous studies have explored various aspects of EV charging load prediction, employing diverse methodologies and theoretical frameworks. While existing research has made notable progress, much of it focuses on predicting the overall charging load at regional or city-wide levels. However, there remains a significant gap in accurately capturing the spatial and temporal distribution of charging loads. Additionally, data-driven models are often limited in their ability to account for uncertainties in future scenarios. These limitations highlight the need for a more comprehensive forecasting approach that can precisely model the spatial and temporal dynamics of EV charging loads across different scenarios. In response to these challenges, this paper proposes a methodology that integrates both transportation and power distribution networks while incorporating multiple influencing variables. This approach not only addresses the evolving demands of the EV landscape but also offers more reliable decision-making support for the planning of charging infrastructure and grid management.

Novelty and key contributions

This paper constructs a spatio-temporal distribution prediction model for EVs charging load in transportation-power coupled network. The contributions are as follows:

-

(1)

The method proposed in this study is based on the transportation-power coupled system, which can make a more precise prediction of the charging demand of EV users in cities.

-

(2)

Unlike previous studies that typically tend to focus on the influence of one or two factors, by considering multiple uncertain factors, this research provides predictions that are closer to real-world conditions, enhancing the accuracy and reliability of the method.

-

(3)

This study establishes multiple scenarios for simulation analysis. By comparing the distribution results of different scenarios, the rules can be showed more comprehensively, thereby laying a reliable foundation for subsequent research.

Paper layout

The structure of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 analyzes of the travel characteristics and routes of different types of EVs using the Dijkstra algorithm. It establishes a model for the EV power consumption and charging behavior, introduces the construction methods of the transportation network and power distribution network models, and proposes a charging load prediction method based on the spatial and temporal distributions of EVs across multiple scenarios. Section 3 introduces the methods and presents a complete framework for predicting the spatio-temporal distribution of regional EV charging loads, which is validated using data from a real urban area and discussed in detail in Sect. 4. Finally, Sect. 5 summarizes the key findings of the study and suggests potential directions for future research.

Spatio-temporal distribution prediction model of EVs charging load in TPCN

EVs classification and mobility characterization

EVs can be broadly classified into two main categories: passenger cars and commercial vehicles. Passenger cars are primarily designed and engineered for transporting passengers and their luggage, with a seating capacity of up to nine, including the driver. Commercial vehicles, on the other hand, encompass all goods vehicles and buses with more than nine seats. Given the current landscape of electric vehicle development and the distinct functions of these vehicles types, passenger cars are typically subdivided into three categories: private cars, taxis and official vehicles. Commercial vehicles can be further classified into buses, express logistics vehicles, sanitation vehicles, and engineering repair vehicles (which specifically include emergency repair vehicles for utilities, such as electricity and drainage, but excluding large-scale engineering and freight vehicles). Unlike passenger cars, commercial vehicles tend to follow more fixed routes and have predictable charging locations. Therefore, this study focuses on the analyzing the travel behavior and predicting the charging loads for electric vehicles within the passenger car category.

Characterization of commuter trips by private EVs

The demand for user charging is closely linked to travel patterns. Predicting the expected electricity demand for EVs based on the travel characteristics of EV users has been demonstrated to be an effective approach24. A robust characterization of user travel demand within urban transportation networks provides a critical foundation for accurately forecasting the charging loads.

For EVs, a trip typically comprises three key events - departure, destination parking, and a potential charging event at the destination or parking lot25. The routes taken by private EVs are generally more predictable, primarily revolving around commutes between residential and work locations26. EV usage tends to peak during morning and evening commuting hours, with significantly lower activity throughout the rest the day. Private EVs are often parked at workplaces or offices during the day on weekdays, and at home during the evenings. This results in extended parking periods, particularly overnight when charging opportunities are more readily available. Additionally, weekends or holidays may see an increase in travel frequency and longer trips, including the possibility of occasional long-distance travel.

The trip chain analysis method can effectively simulate the daytime travel behavior of private EV users, closely mirroring actual user routines. A Trip chain refers to the sequence of travel activities an individual undertakes, delineated by changes in time and location. It involves the process by which an individual departs from an origin point, at a specific time, uses a particular mode of transportation, visits multiple destinations in a defined order, and eventually reaches the final destination, completing the journey27. The National Household Travel Survey (NHTS) data, which provide comprehensive transportation statistics, including details on the date, origin, destination, and purpose of each trip. According to NHTS2022 data, residential travel is dominated by simple chains, where both origins and destinations are primarily home locations, and the longest chain length is three. Given the primary purpose of many trips, it is reasonable to assume that brief stops are less likely to result in charging events.

The primary travel behaviors of private EVs and the proportion of trips associated with each activity are outlined in Table 128,29. Based on the functional characteristics of urban areas, five types of travel destinations can be classified: home (H), work (W), shopping malls (SR), leisure places (SE) and other locations (O).

Where,\(\mu\)and\(\sigma\)represent the mean and variance of the initial moments corresponding to distinct trip chains, respectively. The specific parameters for these distribution are provided in Table 228,29:

Electric taxis travel characterization

Electric taxis operate in shifts, providing near-continuous service throughout the day. Due to their intensive operational nature, they accumulate significantly higher daily mileage compared to private cars, making more trips and covering longer distances. Stops are typically brief, occurring primarily when passengers are picked up, dropped off, or while waiting for new passengers. The high degree of randomness in taxi destinations, driven by unpredictable passenger demand, makes route forecasting challenging. Charging is generally required during service breaks or at shift changeovers, creating a limited window for recharging during operational hours. Consequently, fast charging solutions are often necessary, while slow charging usually takes place during shift transitions in the early morning hours.

Electric taxis primarily transport passengers during the day, with peak operating hours occurring between 6:00 p.m. and 8:00 p.m. Based on the fitted data presented in the literature30, the initial travel times follow the probability distribution in Eq. (2):

Where, \({\lambda _1}\)= 0.389, \({\alpha _1}\)= 7.046, \({\beta _1}\)= 1.086, \({\lambda _2}\)= 0.066, \({\alpha _2}\)= 15.610, \({\beta _2}\)= 9.667.

Official EVs travel characterization

Official EVs serve a wide range of purposes, encompassing government, commercial and specialized. The routes, origins, and destinations of these EVs are more varied, as they often accommodate both work-related official travel and personal use. Official EVs typically make frequent trips with irregular driving patterns, often entering and leaving different locations multiple times throughout the day. Due to the diverse nature of their tasks, the timing and location of their recharging are more dispersed. This can result in charging requirements conflicting with the need for immediate availability during emergency tasks, thus placing higher demands on the strategic placement and scheduling of charging infrastructure.

The majority of initial travel times for official EVs are concentrated during two distinct periods: 7:00–9:00 in the morning and 18:00–20:00 in the evening, exhibiting a typical double-peak pattern. In this study, the statistical data of official car travel times have been analyzed and fitted, and the probability distribution for the initial travel times is expressed in Eq. (3):

Where, \({a_0}\)= 24.58, \({a_1}\)=-16.06, \({b_1}\)=-14.28, \({a_2}\)= 2.119, \({b_2}\)=-10.88, w = 0.2887.

Trip path analysis based on modified OD probability matrix

Due to the high uncertainty in the routes of electric taxis and official cars, the Origin-Destination (\(OD\)) analysis method, which can effectively capture the road peer flow information, is utilized for path planning. The\(OD\)matrix represents the traffic flow between all origins and destinations within the transportation network. Bu using traffic flow observation data provided by the traffic department, it is possible to determine the volume of electric vehicle traffic on the roads during different time periods. With the aid of TransCAD, inverse traffic modelling is employed to derive \(OD\) matrices for varying time periods31. By dividing a day into m time periods, the \(OD\) matrix consists of m submatrices \(B_{{n \times n}}^{{t,t+1}}\), where n is the number of nodes in the region. Each submatrix contains details about the probability of travelling between an origin and destination for each road during the time period t to \(t+1\). According to Eq. (4), the probability of a vehicle travelling from node i to node j at time t is calculated32:

Where, \(b_{{ij}}^{{t,t+1}}\) denotes the vehicle traffic between the origin node i and the destination node j during the time period t to \(t+1\); \(C_{{ij}}^{{t,t+1}}\) represents the trip probability of an EV starting at node i and selecting node j as its destination within the same time period. The \(OD\) probability matrix K for the period t to \(t+1\) is then defined by Eq. (5):

EVs generate destinations through random sampling based on \(OD\) probability matrix according to their type and the specific time period.

In this study, the original \(OD\) matrix is dynamically adjusted. \(g_{{ij}}^{{t,t+1}}\) denote the difference in traffic flow from node i to node j during the time period t to \(t+1\), calculated as:

The diagonal elements of the corrected \(OD\) matrix represent the adjusted traffic flow from the current node i to itself. Let \(B_{{ij}}^{t}\) denote the corrected vehicle traffic between the origin node i and the destination node j during the time period from t to \(t+1\), calculated as follows:

After the dynamic correction of the \(OD\) matrix, the trip probability of selecting a destination can be calculated using Eq. (8):

The traffic situation undergoes dynamic changes throughout the day, particularly during the morning and evening rush hours as well as the midday lull, where traffic flows vary significantly. By dynamically correcting the \(OD\) matrix to account for the possibility of vehicles remaining stationary at a given location, the model’s accuracy can be significantly enhanced, making it more reflective of the real traffic conditions.

EVs power consumption calculation

Velocity-flow model

In the urban traffic system, the travel speed of EVs is primarily influenced by road capacity and traffic flow. To accurately simulate the EV travel process, this study adopts the practical speed-flow model described in the literature33. \({v_{ij}}(t)\), the speed of a vehicle travelling on road segment \(R(i,j)\) at time t, can be described by Eq. (9):

Where, \({v_{ij}}(t)\) represents the free flow speed for road\((i,j)\), and\({c_{ij}}\) is the maximum capacity of road\((i,j)\),which is related to the road class; \({q_{ij}}(t)\) is the volume of traffic on road\((i,j)\) at time t; The ratio of \({q_{ij}}(t)\) and \({c_{ij}}\) is the road saturation at moment t. The term \(\beta\) is an empirical coefficient; while a, b, \(\theta\) are the adaptive coefficients for different road classes, respectively.

In this paper, roads are classified into two categories. For Class I (Arterial Roads), the adaptive coefficients a, b, \(\theta\) are 1.726, 3.15, and 3, respectively. For Class II (Secondary Arterials), the corresponding values are 2.076, 2.870, and 3.

Energy consumption calculation

The energy consumption per unit mile of an Ev’s battery is influenced by several factors, including ambient temperature, traffic conditions and the use of the air conditioning systems34,35,36,37. These factors, in turn, affect the vehicle’s charging load. While many studies focus on the chemical and physical properties of the batteries when predicting charging loads, they often overlook the real-world driving conditions of EVs. Since the average driving speed varies significantly across the road classes, it impacts the energy consumption of EVs. The energy consumption per unit mile for EVs across various road classes can be expressed as38:

Where \({E_f}\), \({E_a}\), \({E_s}\) and \({E_b}\) denote the energy consumption per unit mile for Expressways, Arterial Roads, Secondary Arterials and Collector Roads, respectively.

In this paper, we focus on the energy consumption per unit mile for EVs under varying temperature conditions, considering the impact of air conditioning usage. This is expressed as the ratio of the energy consumption per unit mile with the air conditioning turned on to that with the air conditioning off. The higher this ratio, the greater the energy consumption per unit mile of the EV when air conditioning is in use. After fitting the data, the temperature-energy ratio coefficient of the battery \({K_{temp}}\) is calculated using Eq. (11)39:

Where T is the current ambient temperature.

According to the curve fitting results in Eq. (11), the actual unit energy consumption E of an EV travelling on the current road r at the current temperature T with the air conditioning on is given by:

Where, \({E_r}\) is the standard energy consumption for the specific road class r, taking the values of \({E_f}\), \({E_a}\), \({E_s}\) and \({E_b}\), respectively.

EVs charging behavior model

The charging choice model formulates the decision-making process of EV user when selecting a specific charging location, taking into account the flexibility in charging time, power using time, spatial factors, and energy consumption parameters to predict the demand for EV charging10. In this study, a charging demand model is constructed based on a detailed analysis of the charging characteristics of different types of EVs. This model aims to accurately describe the charging behavior of EV users at specific nodes.

Analysis of EVs charging behaviors

The travelling patterns of electric private cars are characterized by long parking duration, sufficient charging windows, and relatively fixed driving destinations. Key charging locations for these vehicles include office areas, residential zones, large-scale superstores, and integrated commercial-residential areas. Given that high-power fast charging may lead to fast battery degradation3, slow charging is typically preferred by private car users. Numerous studies on EV charging behavior and travel data suggest that the battery range of EVs is generally sufficient for most users’ urban travel needs, making emergency charging a rare occurrence. Therefore, private EV users tend to charge at home or at work rather than at public charging stations40,41.

Private car owners usually weigh the advantages and disadvantages of charging at different locations. For example, public charging stations typically charge fees, which may be higher than those incurred at home or workplaces, but they often come with perks such as reserved parking spaces at leisure ord entertainment venues42. In general, most private EV charging events occur at home43, followed by workplaces or commuting locations40. Nighttime charging at night is preferred by users due to its greater convenience and flexibility than daytime charging. Therefore, in this paper, the charging behavior of private cars is modeled by considering the need to charge upon arrival at a destination, while slow charging is assumed to take place at home at the end of the day’s travel if the SOC falls below a set psychological threshold.

Electric taxis, primarily engaged in passenger transport during the day, face more urgent charging needs due to the demand for profitability. Consequently, it is assumed that electric taxis will chose the nearby fast charging station when the remaining SOC drops below a set threshold during operational hours, while slow charging is concentrated during the shift change window from midnight to 6:00 a.m.

Official EVs include private official EVs, business EVs and functional EVs. Their travel behavior is intermittently distributed throughout the day, and their destinations exhibit a certain degree of randomness44. Depending on the remaining power, the distance to the next destination, and the travel time interval between trips, official EVs may either opt for fast-charging at a nearby node when the remaining SOC drops below the threshold, ensuring they meet the mileage requirements for the next trip, or choose fast-charging or slow-charging based on the available dwell time at the destination. Considering the typical daily patterns of urban residents, Official EV travel is assumed to conclude by 10:00 p.m.

Charging decision model

Previous studies have often simplified the charging behavior of an individual EV users by assuming one of two decision strategies: either ‘charge immediately after the trip’ or ‘charge after the trip only if the energy required for the next trip cannot be met’. However, this approach does not accurately reflect real-world charging behavior, as it overlooks the inherent uncertainty in the charging demand of private EVs.

In practical, a user’s charging demand depends on whether the current SOC can meet the requirement of the next trip. If the SOC is insufficient, charging is inevitable. However, if the SOC is adequate, the need to charge becomes uncertain and tends to diminish as the available SOC increasingly exceeds the energy demands of the upcoming trip. To capture this complexity, a charging demand model is established, triggered by the user’s arrival at a destination, and accounts for both the necessity and the uncertainty of charging based on the current SOC and future travel needs.

In categorizing private EV users based on the current SOC, they can be divided into elastic and inelastic users. This classification hinges on the elasticity coefficient, denoted as \({u_1}\). Let\({A_s}\) represent the SOC at the current moment. if \({A_s} < {u_1}\), the current SOC cannot meet the demand of the next trip, resulting in mileage anxiety and necessitating immediate charging. These users are defined as inelastic. Conversely, if \({A_s} \geq {u_1}\), the current SOC is sufficient for the upcoming journey, categorizing these users as elastic.

Fuzzy theory is utilized in the analysis of charging demand for elastic users. In this framework, a fuzzy set M represents the presence of charging demand, with the membership degree represented by an membership function \(M({A_s})\). This function assigns values within the interval [0,1]45. The membership degree is given by Eq. (13):

Where, \(M({A_s})\) is the membership degree of \({A_s}\) to M, \({u_1}\) is the elasticity coefficient and \({u_2}\) is the fuzzy coefficient. If \({A_s} \geq {u_2}\), the current SOC can meet the next trip, indicating no need for charging; if \(u_{1} \le A_{s} < u_{2}\), the closer \({A_s}\) is to \({u_2}\), the closer \(M({A_s})\) is to 0, indicating a weaker need for charging; the closer \({A_s}\) is to \({u_1}\), the closer \(M({A_s})\) is to 1, indicating a stronger need for charging. If \(A_{s} < u_{1}\), \(M({A_s})\) is 1 and the EV user must chose to charge. In this analysis, \({u_1}\) is set to 0.3 and \({u_2}\) is set to 0.8.

For electric taxis and official EVs, charging demand is triggered when \({A_s}\) is below the threshold while driving. In such cases, the charging load is assigned to the nearest charging node The decision condition for triggering this charging demand is represented by Eq. (14):

Where \({C_s}\) is battery capacity of EV;\(\varepsilon\) is charging threshold. To account for the user’s range anxiety, the value of \(\varepsilon\) is set to 0.3.

To mitigate the detrimental effects of overcharging on battery life, this study sets the post-charging SOC to 90% of the battery capacity. The method for calculating the charging time of EVs is presented by Eq. (15):

Where \({T_e}\) is the charging time of EV and \({P_t}\) denotes the charging power, which varied based on the charging type selected by the user.

For a private EV with a specific parking during, if charging to a full SOC is not feasible within the available parking time at the destination, the vehicle is charged up until the start of next trip. The SOC of the EV at the initial time of the next trip is calculated using Eq. (16):

Where \(SO{C_s}\) is the SOC of the EV at the start of the next trip, \({t_d}\) is the EV’s parking time at the current destination, and \(\eta\) represents the charging efficiency of the EV, which ranges from 0.9 to 1.

For the official EV, if the next destination, as determined by the modified \(OD\) probability matrix, is the node where the vehicle is currently located, it is assumed that the driver chooses to stop at the current node. Depending on the functional area to which the node belongs, the parking time at this location with different probability distributions can be modeled as Eq. (17)-Eq. (19) .

Where, the parking time in the H region follows the Weibull distribution described by Eq. (17), the parking time in the W region adheres to the generalized extreme value distribution shown in Eq. (18), and the parking time in the SR/SE/O region follows the generalized extreme value distribution specified in Eq. (19).

After generating the appropriate parking time based on these distribution functions, if the parking time is insufficient to achieve a full charge, the actual charging time is calculated using Eq. (20):

Where \({t_p}\) is the charging time of the official EV at the current node.

Transportation-power coupled network (TPCN)

Transportation network

The graph-theoretical analysis method is employed to abstract the transportation network into an empowered directed graph, which describes the topological features of the network. In this graph, road sections with identical road attributes are represented as directed edges, while the connection points between these road sections are modeled as nodes The dynamic transportation network model, based on time segmentation, is described as follows:

Where G denotes the transportation network of the region; N is the set of all node information in the graph G; while R represents the set of all roads in the graph Gand \({T_m}\) denotes the set of time segments, dividing the entire day into m time segments, wit \({t_m}\) representing the \(mth\) time segment. The road weights are denoted by W, of which the element \({w_{ij}}\) refers to the weight between node i and node j. The weight represents the expenditure for the EV while travelling on the road and can include factors such as road length passage speed, travel cost, etc., which are essential for EV path planning.

As shown in Eq. (22), the element \({d_{ij}}\) represents the connection relationship between node i and node j in the transportation network. The connection relationships of all nodes in the transportation network set G are described by the adjacency matrix D, which consists of the element \({d_{ij}}\) as defined in Eq. (23):

Where, \({w_{ij}}\) denotes the weight of the road between node i and node j. This weight is assigned a value of 0 when \(i=j\), indicating that the weight of a road connecting a node to itself is zero. The term \(Inf\) indicates that there is no direct connectivity between node i and node j.

Power distribution network

In the TPCN, the power distribution network nodes are spatially coupled with the transportation network nodes, necessitating the establishment of a distribution network model that aligns with the transportation network. For the modeling of the power distribution network, it is primarily divided into two components: the network topology model and power flow calculations. Let the set of network nodes be \({N_p}\), the set of branches be \({M_p}\), and the matrix of branch electrical parameters be \({\varphi _p}\). Together, these components form the network \({G_p}=\left( {{N_p},{E_p},{\varphi _p}} \right)\). The network topology can be expressed as follows:

Where, \({n_{pg}}\) is the number of nodes, and the parameters in the branch parameter matrix \({\varphi _p}\) represent the resistance \({r_i}\), reactance \({x_i}\), conductance \({c_i}\), and line power flow \(P_{i}^{m}\), respectively.

Power flow calculation is a fundamental method for analyzing steady-state power system operation. It involves calculating the nodal voltages and power distributions based on the given nodal line parameters to estimate the system’s operating state. For each node in the network, the nodal voltage value is determined using the nodal power equation in the power system’s power flow calculation:

Where, \({P_i}\) and \({Q_i}\) are the injected active power and injected reactive power at node i, respectively; \({V_i}\) and \({V_k}\) are the voltage magnitudes at node i and node k, respectively; \({\delta _i}\) and \({\delta _k}\) are the phase angles of node i and node k, respectively; \({G_{ik}}\) and \({B_{ik}}\) are the conductance and the susceptance between node i and node k.

The solution to Eq. (25) can be obtained through iterative computation using the Newton-Raphson iteration method. The results from the power flow calculation can be used to assess the voltage stability of the electrical system.

Finally, the charging load demand generated by EVs on the transportation network, as partially obtained in Sect. 2.1 to 2.3, is mapped to the corresponding nodes within the distribution network based on the established correspondence. These loads are then aggregated to determine the total charging load at each node of the distribution network, as illustrated in Eq. (26):

Where, \({P_g}\left( t \right)\) represents the total charging load demand at node d at time t for EVs under uncoordinated charging, \({P_d}\left( t \right)\) denotes the base load demand at node d at time t, and \({P_{di}}(t)\) is the charging load demand generated by the ith EV at this node at time.

Methodology

Path planning based on Dijkstra Algorithm

The most commonly used shortest path planning algorithms include the Floyd algorithm and Dijkstra algorithm. The Dijkstra algorithm is a single-source shortest path algorithm suitable for non-negative weighted networks. It is favored for its adaptability to dynamically updated transportation conditions and offers significant advantages in terms of computational speed, stability and practical engineering feasibility46,47.

In an empowered directed graph, let Q represent the set of vertices in the graph, which is divided into two subsets: S, the set of vertices for which the shortest paths have already been determined, and U, the set of vertices for which the shortest paths are yet to be determined. The algorithm starts from an initial node, labeled V. The steps of the algorithm, as described by48, are as follows:

Step 1: Initialization. \(l({u_0})\)is the shortest path length, let\(l({u_0})=0\), for\(v \ne {u_0}\), \(l(v)=\infty\), \({S_0}=\left\{ {{u_0}} \right\}\), \(i=0\).

Step 2: Update Path Lengths. For each\(v \in {\bar {S}_i}({\bar {S}_i}={V \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {V {{S_i}}}} \right. \kern-0pt} {{S_i}}})\), replace\(l\left( v \right)\)by \(\mathop {\hbox{min} }\limits_{{u \in {S_i}}} \left\{ {l(v),l(u)+w(uv)} \right\}\), \(w(uv)\) is the distance at which u and v are directly connected.

Step 3: Select Minimum Distance Vertex. Calculate \(\mathop {\hbox{min} }\limits_{{u \in {S_i}}} \left\{ {l\left( v \right)} \right\}\). Let \({u_{i+1}}\) denote the vertex that reaches this minimum value, and\({S_{i+1}}={S_i} \cup \left\{ {{U_{i+1}}} \right\}\).

Step 4: Termination. If \(i=\left| V \right| - 1\), the process stops; if \(i < \left| V \right| - 1\), replace i with \(i+1\) and repeat from step 2.

In this study, the distance of the road segments is used as the resistance weights, and the Dijkstra algorithm is employed to determine the shortest travel path for an EV from a source node to a destination node.

Monte Carlo simulation

Based on the models and analytical methods represented above, Monte Carlo simulation is set up to obtain the uncertainty parameters for each EV and predict the spatio-temporal distribution of charging loads. Monte Carlo simulation is widely used in research problems in various fields. It adopts the method of repeated random sampling to produce the distribution of possible result values through multiple iterations. The mathematical foundation of this method is rooted in the Law of Large Numbers, which asserts that as the number of trials increases, the sample average value derived from the simulations converges towards the expected, true average value.

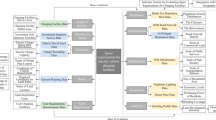

Spatio-temporal distribution prediction framework for EV charging loads in TPCN

In summary, this paper first analyzes the travel characteristics and paths of different types of EVs and plans the trip paths using the Dijkstra algorithm. It then establishes models for EV power consumptions and charging decisions, and constructs the transportation network model and an appropriate distribution network model. Subsequently, the charging demand is mapped to the corresponding nodes of the distribution network to obtain the charging demand distribution results over a 24-hour period. The specific process of the spatio-temporal distribution prediction framework for charging loads in a transportation-power coupled network (TPCN) is shown in Fig. 1:

According to the prediction framework established in Fig. 1, the method flow of the spatio-temporal distribution prediction framework for charging loads in a TPCN is as follows:

Step 1: Model the Networks. First, the transportation network and power network in the selected area are modeled, and different types of EVs are introduced at each road node.

Step 2: Generate EV Parameter. Monte Carlo sampling method is used to generate the characteristic parameters for EVs, including destination, initial time, departure time and initial SOC.

Step 3: Plan Trip Paths. The Dijkstra algorithm is applied to plan the optimal trip path for each EV. Update the EV parameters in real-time while travelling, such as remaining SOC, travel distance, and so on.

Step 4: Apply Charging Decision Models. Different charging decision models are utilized based on the type of EV. When an EV triggers charging demand, it is charged at the destination node where it arrives, with options for either fast or slow charging modes.

Step 5: Aggregate Charging Information. The charging information of each vehicle is recorded and then aggregated in the EV charging demand loads at each node at the current time to obtain the spatial and temporal distribution of EV charging loads.

Step 6: Perform a power flow calculation. A power flow calculation is conducted on the power network to analyze the potential impact of large-scale EV charging behavior on the network, and then to assess the stability and reliability of the power network based on these calculations.

In order to better illustrate the logical relationship and implementation process of each submodule in the method, Fig. 2 provides a pseudo-code of the overall process.

Result and discussion

In this paper, a regional transportation network within a city is selected for case study analysis, as depicted in Fig. 349. This network is employed to simulate the charging load demand on both a typical weekday and weekend and weekend. The region includes 29 nodes and 49 roads, categorized into four functional areas: Residential area 1 (nodes 1–11), Residential area 2 (nodes 12–16), Work area (nodes 17–20), and Commercial, social and recreational and other area (nodes 21–29), based on the varying functions of the destinations. The IEEE33-node standard distribution network is selected and its parameters are slightly modified to better reflect the conditions of the study region. Each distribution node within the region is physically coupled with the corresponding transportation node. The charging load at a distribution node k at time t represents the cumulative charging power of the EVs connected to this node. The simulation environment is MATLAB2022b. The temporal resolution of the simulation is set at a 15-minute interval.

Referring to the city’s 0.88% of total car ownership rate in 2022, the test region is assumed to have 15,000 private EVs, 1,000 electric taxis and 1,000 official EVs. The battery capacities are set as follows: 30 kWh for private EVs, which can meet daily commuting needs; 50kWh for official EVs; and 80kWh for electric taxis. The initial SOC for EVs follows a normal distribution \(N(0.8,0.1)\). he simulation spans 24 h, divided into 96 time slots with a 15-minute interval, to enhance prediction accuracy. The parameters for the simulation are detailed in Table 3.

Comparative analysis of EVs charging demands at various temperatures

The load demand statistics for different functional areas under two typical conditions-standard normal temperature (approximately 20 °C) and high temperature with air conditioning-are presented in Table 4. The data indicates that the load demands across all functional area, as well as the total load demand, increase when the air conditioners are switched on. Specifically, the percentage of charging load demand in work and commercial areas rises, while the percentage in residential areas decreases. This shift is attributed to the increased power consumption of EVs traveling during the daytime, which reallocates some of the evening and nighttime charging demand to the daytime.

In summary, for the same driving characteristics, the total charging demand rises with the activation of air conditioning. A comparison of the slow to fast charging load ratios across different regions, shown in Figs. 4 and 5, reveals that hot weather significantly impacts electric taxis, which are on the road nearly all day. This results in increased power consumption and creates additional demands for fast charging.

Analysis of spatial distribution of EVs charging demands

Figures 6 and 7 illustrate the frequency of charging demand events for different types of EVs at each road node on typical weekday and weekends, respectively.

Private EVs predominantly generate charging demands in residential and commercial areas, particularly concentrated at nodes 1–20. Although private EVs continue to produce more charging events in residential and work areas on weekends, the number of charging events for each node decreased compared to weekdays. Conversely, there is a significant increase in the number of charging events in the commercial area on weekends compared to usual, likely due to the fact that more people choose to travel for purposes such as recreation activities, dining, and shopping. Electric taxis and official EVs, on the other hand, do not show significant changes in the number of charging events between weekdays and weekends. However, their proportion of total charging events at each node increases during weekends.

Analysis of temporal distribution of EVs charging demands

Figures 8 and 9 show the distribution of charging events across different functional areas during typical weekdays and weekends over a 24-hour period. On weekends, the work area shows a notable absence of the morning peak in charging demand (6:00–9:00) observed on weekdays, aligning with the altered travel patterns typical of weekends. The overall distribution of charging demand in residential and commercial areas is similar on both weekdays and weekends, with charging events concentrated in the afternoon and evening. In residential areas, the peak charging demand occurs between 15:00 and 24:00, coinciding with the return of private vehicle users to their homes, which reflects the residents’ daily commuting patterns. In contrast, the peak demand in commercial, social, recreational and other areas occurs later, between 09:00 and 24:00. This shift aligns with users frequenting these areas as destinations after work hours, following the end of the peak EV occupancy period and when official EVs typically cease their daily operations.

Analysis of spatio-temporal distribution of charging load demands

Figures 10 and 11 show the statistical results of charging load demand for each node and each time period during typical weekdays and weekends, respectively. These figures visualize the temporal and spatial distribution characteristics of charging load demand. A comparison of the two figures indicates an uneven distribution of charging load demand both temporally and spatially, with significant variations in the peak demand across different types of days.

On weekdays, a mini-peak in charging demand is observed between 6:00 and 12:00, predominantly at nodes within the work area. This pattern is attributable to users opting to charge their vehicles upon arriving. In the afternoon, charging demand decreases compared to the morning and is more spatially distributed, with reduced concentration in the work area. By evening, there is a significant surge in charging demand across all nodes.

Overall, charging demand on weekends is lower than on weekdays, primarily due to a reduced number of trips made by private EV users. During weekends, charging demand between 6:00 to 12:00 is both lower and more dispersed compared to weekdays, as many users do not need to commute to work, eliminating the daytime charging peak. This reduction is further attributed to users generally delaying their travel on weekends. The total charging demand on weekends is concentrated in the period after 12:00. Spatially, there is a significant decrease in charging demand at residential area nodes compared to weekends. This reduction is partly because fewer users travel on weekends, leading to less electricity consumption, and partly because more users choose commercial, social and recreational areas and as destinations. Additionally, some users prefer taking taxis over self-driving, contributing to the shift in demand. These observation are consistent with the earlier findings on changes in the percentage of demand for fast charging.

Comparative analysis of charging load demands by functional areas

Figures 12, 13 and 14, and 15 present the statistics of slow charging demand and total charging demand across different functional areas. The trends in charging demand increase and decrease vary significantly among these areas. The area enclosed by the time axis and the charging demand curves provides an indication of the proportion of slow and fast charging demand relative to the total charging demand throughout the day. In residential and work areas, slow charging demand constitutes most of the total charging demand. This is attributed to the predominance of private EVs, which follow daily commuting routes that frequently include these areas, and because these areas host a higher proportion of private EVs. Conversely, the share of slow charging demand in commercial areas is lower. This is due to the presence of taxis and non-private EVs, which contribute more to traffic flow in these areas, with these vehicles often making repeated trips in locations with higher passenger opportunities.

Regarding daily patterns, peak charging demand in residential areas is concentrated between 17:00 and 24:00, corresponding to the time when residents return home and charge their vehicles. In work areas, night-time charging demand is relatively low, with peak demand occurring between 08:00 and 11:00 as users arrive at their workplaces and charge EVs with SOC below the user’s psychological threshold. In commercial areas, peak charging demand is observed after 12:00, aligning with the increased presence of official EVs on the road and the higher tendency for leisure travel in the afternoon.

Analysis of the impact of EVs charging on the distribution network in different scenarios

Figures 16, 17 and 18 illustrate the distribution network voltage under different conditions: typical weekdays at normal temperature, weekends at normal temperature, and typical weekdays at high temperature. From Fig. 15, it can be seen that during the weekday evening peak (17:00–21:00), the voltage at residential area nodes is generally low, reaching a minimum of 0.91 pu.

On weekends, despite fewer private EVs being on the road, the power network voltages show a wider range compared to weekdays, with the lowest voltage dropping to 0.90 pu. The low voltage levels are predominantly observed at nodes numbered 1–16, which are located in the residential area. This is attributed to the increased demand for fast-charging loads on weekends. Notably, the duration during which the voltage approaches the lower limit on weekends is longer than on weekdays, although significant voltage drops occur later, primarily after 18:00. Therefore, for periods of peak charging on weekends and in areas with extensive EVs connection, further research is needed to develop effective methods for managing EV charging in an orderly manner.

Conclusions and future work

Conclusions

With the growing number of EVs, addressing the charging problem presents both challenges and opportunities. This study proposes a method for predicting the spatial and temporal distribution of EV charging loads, utilizing a transportation-power coupled network and considering multiple influencing factors. The effectiveness of this method is validated through simulation and analysis in an urban region, leading to the following key conclusions:

-

(1)

The study demonstrates significant variations in EV charging loads across different nodes, with distinct patterns emerging between weekdays and weekends. On weekdays, the charging load demonstrates a double-peak pattern in the morning and evening, whereas, on weekends, the peak is mainly concentrated in the evening. These findings provide new perspectives for understanding the charging behavioral characteristics of EVs.

-

(2)

The prediction method proposed in this paper can accurately simulate the daily driving and charging behaviors of different types of EVs. By incorporating dynamic traffic flow, air temperature variations, and user driving patterns, the model achieves a high level of accuracy in forecasting the spatial and temporal distribution of charging loads in a specific region.

-

(3)

The transportation-power network coupling method proposed in this paper allows for a detailed analysis of charging load distribution. This refined analysis indicates the spatial and temporal changes in charging load, providing an important reference for the optimal placement and planning of charging facilities in urban regions.

-

(4)

Unlike previous studies, which predict EV charging load at a broader city or regional level, this method focuses on specific road nodes. This advancement offers a more granular and forward-looking perspective, supporting the future planning of additional charging facilities in the context of large-scale EV integration.

Limitations of the work and future research

This paper focuses on a method to predict the temporal and spatial distribution of EVs charging load in the coupled network of urban. Limited to the length of the paper, the possible impact of Vehicle-to-Grid (V2G) mode on users’ charging demand and power grid is not discussed. Looking ahead, the interaction between EVs and the grid can be further considered to research the potential of users’ participation in V2G under policy guidance. On this basis, the optimal plan of EV charging infrastructure can be considered. Besides, with widespread adoption of EVs is likely to exacerbate peak load issues during high temperatures periods and weekends, potentially increasing the operational burden on power grid and impacting the safety of power grids. Future research will focus on developing optimal scheduling strategies to mitigate the effects of large-scale EV integration on power systems.

Data availability

The datasets used in/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Bayram, I. S., Devetsikiotis, M. & Jovanovic, R. Optimal design of electric vehicle charging stations for commercial premises. Energy Res. 46, 10040–10051 (2022).

Fischer, D., Harbrecht, A., Surmann, A. & McKenna, R. Electric vehicles’ impacts on residential electric local profiles–A stochastic modelling approach considering socio-economic, behavioural and spatial factors. Appl. Energy. 233, 644–658 (2019).

LaMonaca, S. & Ryan, L. The state of play in electric vehicle charging services – A review of infrastructure provision, players, and policies. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 154, 111733 (2022).

Kunj, T., Pal, K. & Networks, I. Optimal location planning of EV Charging Station in Existing Distribution Network with Stability Condition, in 2020 7th International Conference on Signal Processing and (SPIN)IEEE, pp. 1060–1065. (2020).

Zhang, J. et al. Charging demand prediction in Beijing based on real-world electric vehicle data. J. Energy Storage. 57, 106294 (2023).

Liu, Y. S., Tayarani, M. & Gao, H. O. An activity-based travel and charging behavior model for simulating battery electric vehicle charging demand. Energy (Oxf). 258, 124938 (2022).

Liu, Y., Liu, W., Gao, S., Wang, Y. & Shi, Q. Fast charging demand forecasting based on the intelligent sensing system of dynamic vehicle under EVs-traffic-distribution coupling. Energy Rep. 8, 1218–1226 (2022).

Xydas, E. et al. A data-driven approach for characterising the charging demand of electric vehicles: a UK case study. Appl. Energy. 162, 763–771 (2016).

Arias, M. B. & Bae, S. Electric vehicle charging demand forecasting model based on big data technologies. Appl. Energy. 183, 327–339 (2016).

Li, X. et al. Electric vehicle behavior modeling and applications in vehicle-grid integration: an overview. Energy (Oxf). 268, 126647 (2023).

Heydarian-Forushani, E., Golshan, M. E. H. & Shafie-khah, M. Flexible interaction of plug-in electric vehicle parking lots for efficient wind integration. Appl. Energy. 179, 338–349 (2016).

Jawad, S. & Liu, J. Electrical vehicle charging load mobility analysis based on a spatial–temporal method in Urban Electrified-Transportation Networks. Energies (Basel). 16, 5178 (2023).

Williams, B., Bishop, D., Hooper, G. & Chase, J. G. Driving change: Electric vehicle charging behavior and peak loading. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 189, 113953 (2024).

Kang, J., Kong, H., Lin, Z. & Dang, A. Mapping the dynamics of electric vehicle charging demand within Beijing’s spatial structure. Sustain. Cities Soc. 76, 103507 (2022).

Liu, K. & Liu, Y. Stochastic user equilibrium based spatial-temporal distribution prediction of electric vehicle charging load. Appl. Energy. 339, 120943 (2023).

Lin, H. et al. Characteristics of electric vehicle charging demand at multiple types of location - application of an agent-based trip chain model. Energy (Oxf). 188, 116122 (2019).

Yang, J. et al. Charging demand analysis framework for electric vehicles considering the bounded rationality behavior of users. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 119, 105952 (2020).

Hu, L., Dong, J. & Lin, Z. Modeling charging behavior of Battery Electric Vehicle drivers: a cumulative Prospect Theory Based Approach. Transp. Res. Part. C: Emerg. Technol. 102, 474–489 (2019).

Zhang, J., Yan, J., Liu, Y., Zhang, H. & Lv, G. Daily electric vehicle charging load profiles considering demographics of vehicle users. Appl. Energy. 274, 115063 (2020).

Bordin, C. & Tomasgard, A. Behavioural change in green transportation: micro-economics perspectives and optimization strategies. Energies (Basel). 14, 3728 (2021).

Dayem, K., Mercier, C., May-Ostendorp, P. & Consulting, X. Electric Vehicle Charging Control Strategies (National Rural Electric Cooperative Association’s Business and Technology Strategies dept., 2019).

Kunj, T. & Pal, K. Two-way energy management of electric vehicle charging station. Int. J. Power Energy Syst. 44, 1–8 (2024).

Kunj, T. & Pal, K. EVs owner benefit evaluation through energy exchange in the smart radial distribution network. Electr. Power Compon. Syst. 52, 1513–1527 (2024).

Pareschi, G., Küng, L., Georges, G. & Boulouchos, K. Are travel surveys a good basis for EV models? Validation of simulated charging profiles against empirical data. Appl. Energy. 275, 115318 (2020).

Sun, M. et al. Uncovering travel and charging patterns of private electric vehicles with trajectory data: evidence and policy implications. Transp. (Dordrecht). 49, 1409–1439 (2022).

Mu, Y., Wu, J., Jenkins, N., Jia, H. & Wang, C. A spatial–temporal model for grid impact analysis of plug-in electric vehicles. Appl. Energy. 114, 456–465 (2014).

Chen, Y. & Akar, G. Using trip chaining and joint travel as mediating variables to explore the relationships among travel behavior, socio-demographics, and urban form. J. Transp. Land. Use. 10, 573–588 (2017).

Liu, Z. et al. Spatial-temporal distribution prediction of charging loads for Electric vehicles considering vehicle-Road-Station-Grid Integration. Autom. Electr. Power Syst. 46, 36–45 (2022).

Jiang, Z., Xiang, Y., Liu, J., Zhu, J. & Shui, Y. Charging load modeling Integrated with Electric Vehicle Whole Trajectory Space and its impact on distribution network reliability. Power Syst. Technol. 43, 3789–3799 (2019).

Sun, Y., Qi, T. & Zhao, Y. Research on location and capacity determination of Charging stations under the Coupling of Road and Electrical Networks considering V2G potential of Electric vehicles. Integr. Intell. Energy. 46, 1–10 (2024).

Zhang, L. et al. OD matrix based spatiotemporal distribution of EV charging load prediction. Power Syst. Prot. Control. 49, 82–91 (2021).

Krishnakumari, P., van Lint, H., Djukic, T. & Cats, O. A data driven method for OD matrix estimation. Transp. Res. Part. C: Emerg. Technol. 113, 38–56 (2020).

Luo, X., Du, J. & Chen, Y. Analyses on Mult-i Traffic Flowʾs characteristics. J. Southwest. Jiaotong Univ. 35, 297–300 (2000).

Yi, T., Zhang, C., Lin, T. & Liu, J. Research on the spatial-temporal distribution of electric vehicle charging load demand: a case study in China. J. Clean. Prod. 242, 118457 (2023).

Wang, D. et al. Modeling of plug-in electric vehicle travel patterns and charging load based on trip chain generation. J. Power Sources. 359, 468–479 (2017).

Yan, J. et al. EV charging load simulation and forecasting considering traffic jam and weather to support the integration of renewables and EVs. Renew. Energy. 159, 623–641 (2020).

Hao, X., Wang, H., Lin, Z. & OuYang, M. Seasonal effects on Electric Vehicle Energy Consumption and driving range: a Case Study on Personal, Taxi, and Ridesharing vehicles. J. Clean. Prod. 249, 119403 (2020).

Yao, E., Yang, Z., Song, Y. & Zuo, T. Comparison of Electric Vehicle’s energy consumption factors for different Road types. Discrete Dyn. Nat. Soc. 2013, 328757 (2013).

Yi, T., Zhang, C., Lin, T. & Liu, J. Research on the spatial-temporal distribution of electric vehicle charging load demand: a case study in China. J. Clean. Prod. 242, 118457 (2020).

Hardman, S. et al. A review of consumer preferences of and interactions with electric vehicle charging infrastructure. Transp. Res. Part. D: Transp. Environ. 62, 508–523 (2018).

Azadfar, E., Sreeram, V. & Harries, D. The investigation of the major factors influencing plug-in electric vehicle driving patterns and charging behaviour. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 42, 1065–1076 (2015).

Chakraborty, D., Bunch, D. S., Lee, J. H. & Tal, G. Demand drivers for charging infrastructure-charging behavior of plug-in electric vehicle commuters. Transp. Res. D. 76, 255–272 (2019).

Franke, T. & Krems, J. F. Understanding charging behaviour of electric vehicle users. Transp. Res. Part F. 21, 75–89 (2013).

Li, L. et al. Electric Vehicle charging demand prediction model based on dynamic traffic information and its impacts on distribution networks. Power Syst. Clean. Energy. 36, 107–118 (2020).

Liu, H., Zhang, X., Liu, C., Zhang, J. & Ge, S. Timing interactive analysis of Electric private vehicle traveling and charging demand considering the sufficiency of charging facilities. Proc. Csee. 38, 5469–5478 (2018). 18.

Li, Z., Tang, P., Zeng, X., Xiao, R. & Zhao, T. Method of traveling wave fault location based on Dijkstra algorithm in power grid. Autom. Electr. Power Syst. 42, 162–168 (2018).

Tang, D. & Wang, P. Probabilistic modeling of nodal charging demand based on Spatial-Temporal Dynamics of Moving Electric Vehicles. Ieee Trans. Smart Grid. 7, 627–636 (2016).

Baeza, D., Ihle, C. F. & Ortiz, J. M. A comparison between ACO and Dijkstra algorithms for optimal ore concentrate pipeline routing. J. Clean. Prod. 144, 149–160 (2017).

Shao, Y. et al. A spatial-temporal charging load forecast and impact analysis method for distribution network using EVs-traffic-distribution model. Proc. Csee: Smart Grid. 37, 5207–5219 (2017).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Social Science Fund of China (Project No. 24BJY141) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Project No. 72472050).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A and B contributed to methodology and writing the original draft, while C handled formal analysis. D was responsible for project administration and supervision, and F managed data curation and provided supervision. G and H conducted validation and investigation. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, X., Yun, J., Zhou, S. et al. A spatiotemporal distribution prediction model for electric vehicles charging load in transportation power coupled network. Sci Rep 15, 4022 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88607-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88607-y