Abstract

Travel time estimation (TTE) is a critical function in intelligent driving systems. Current research and applications related to TTE primarily focus on urban environments. The objective of this study is to develop TTE methods that are applicable to wilderness areas characterized by plateau and mountainous topography. We selected Transformer, which has greater robustness in capturing long-distance dependencies than LSTM, to develop a Transformer-based model. The model simultaneously integrates positional encoding and multi-head self-attention mechanisms with the objective of enhancing the accuracy of travel time predictions based on a substantial number of trajectory points in wilderness settings. A meta-learning strategy was employed to improve the model’s generalization ability, thereby ensuring its applicability for accurate travel time estimation across a range of challenging environments. Two datasets were constructed based on measurements from two selected areas in eligible plateau and mountainous regions of western China. For each dataset, two categories of features were defined: terrain-weather features and spatio-temporal features. These categories were established in accordance with the influence of seven specific features on traffic conditions in both urban and wilderness areas. Experiments were conducted on both datasets utilizing terrain-weather features. When evaluated alongside the five models that are most commonly utilized in urban settings, the mean absolute percentage error (MAPE) of our model exhibited a 14.89% improvement in plateau environments and a 12.20% improvement in mountainous environments in comparison with the most effective model, namely MetaTTE-GRU. These findings substantiate the assertion that the proposed model is an effective means of estimating travel times in complex environments, and that it exhibits superior accuracy compared to existing LSTM-based estimation models.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Travel Time Estimation (TTE) is a key technology in path planning1and mobile navigation2. In dynamic path planning3, by accurately predicting the time required to travel from the starting point to the end point, TTEs can help drivers adjust the paths in real time, reduce the waiting time, and choose paths with the shortest expected travel time, thus playing a crucial role in improving travel efficiency4.

At present, the primary application of travel time estimation is in urban traffic, encompassing areas such as route planning and autonomous driving. In practice, fluctuations in urban traffic conditions—such as traffic volume—arising from factors like morning and evening peak hours, holidays, and road intersections often compromise the accuracy of time estimations. This, in turn, affects individuals’ daily lives and work5. To address the demands of urban traffic, a significant body of research has been conducted on predicting travel times in urban environments, yielding a wealth of findings6.

Indeed, in many countries and regions, certain plateau and mountainous areas continue to serve as vital spaces for the survival and development of their residents. Additionally, some plateau and mountainous areas are critically important for various activities, including tourism, resource transportation, disaster relief, and more. However, the natural geographical environment of plateau and mountainous regions is more complex than that of urban environments. Adverse road conditions, fickle weather, and frequent natural disasters all contribute to a challenging and uncertain traffic situation. The intricate traffic conditions engender considerable inconvenience for the local population, hindering their daily activities and work, while also posing great challenges to emergency rescue and disaster relief efforts in these remote areas. Therefore, studying traffic issues in plateau and mountainous areas is of great significance. One of the most crucial research areas is travel time estimation. Accurate prediction of travel times helps optimize driving routes and time management, reduces delays caused by factors such as the change in weather or unclear road conditions, and is essential for improving traffic efficiency, particularly for the success of missions such as emergency rescue and disaster relief7.

It is evident that while recent research on TTE technology has yielded significant advancements and numerous accomplishments, existing TTE methods are primarily developed for urban environments. Consequently, there is a substantial gap in dedicated research focused on travel time prediction in wild environments. This gap is particularly evident in plateau and mountainous regions, which feature unique terrain and complex weather conditions that hinder the accuracy of travel time predictions. Unfortunately, there is also a lack of studies demonstrating that the current methods, successfully employed for travel time estimation in urban areas, are applicable to plateau and mountainous regions.

We believe that this discrepancy stems from the considerable differences in traffic conditions between wilderness and urban environments. Consequently, the current TTE methods are confronted with the following issues:

-

The input features utilized in existing TTE methods are primarily tailored for urban environments, failing to accurately represent the actual traffic conditions found in wilderness areas because the factors influencing travel time estimation in wilderness regions differ significantly from those in urban settings. For example, while traffic volume plays a substantial role in determining travel time in urban areas, its significance in less densely populated regions remains to be thoroughly investigated. The rarity of traffic congestion in these areas raises questions about whether it will emerge as a critical factor in predicting travel time. In wilderness areas, particularly those characterized by plateaus or mountainous terrain, the roads are typically uneven, and the climate is usually capricious. These elements typically contribute to challenging traffic conditions and can have a significant impact on travel time. Conversely, such factors are infrequent in urban environments and can therefore be excluded from considerations when estimating travel time in those settings.

-

Currently, deep learning technology has been extensively applied to TTE8,9, with a variety of prediction models developed. Deep learning-based travel time prediction has emerged as a mainstream approach in current travel time estimation methods. The majority of these models typically employ LSTM for feature extraction10,11,12. LSTM utilizes a sequential processing mechanism based on time steps, where the state of each time step is calculated based on the previous one. Additionally, the gate mechanism is employed to selectively retain or discard input information at each time step, thereby mitigating issues of gradient accumulation and explosion13, which enhances its performance in handling time series data. Nevertheless, the input information at early time steps is gradually diluted or overwritten during multiple updates, resulting in information decay and a decline in the capacity of LSTM to process long sequences of data14. This flaw of LSTM restricts the effective application of current LSTM-based time prediction methods in the wilderness, as accurate time prediction necessitates the processing of long sequences of data in such settings. The reason for this is that the increased complexity of the wilderness environment, which is characterized by diverse topography and a greater number of changes in gradient and direction, necessitates the use of a greater number of trajectory points over the same travel distance compared to an urban environment to achieve accurate predictions of travel time. Consequently, this results in a longer sequence of data that requires processing. Therefore, it is crucial for the predictive model to possess robust capabilities to handle long sequences of data effectively. It is evident that the performance of LSTM-based TTE models is susceptible to deterioration when used to accurately predict time in wilderness environments.

In this study, we proposed a Transformer-based method for estimating travel time, aimed at delivering more accurate and reliable time predictions in plateau and mountainous environments. This approach is designed to enhance work efficiency and safety while meeting the diverse requirements of tasks in these challenging settings. The primary contributions of this paper are as follows:

-

We conducted a study to identify and construct input features suitable for TTE in wilderness environments, specifically in plateau and mountainous areas, and developed two datasets based on the unique environmental characteristics of each setting. Two distinct geographical areas were selected from each region characterized by plateau and mountainous environments for investigation. One dataset pertains to the plateau environment, while the other is associated with the mountainous environment. Each dataset records seven types of key information, namely coordinate, terrain slope, turning angle, weather condition, road attribute, the hour of day, and the day of week. Following an analysis of the varying impacts of these features on traffic in urban and wilderness areas, we identified two categories of features derived from the seven original features, which serve as input features for TTE. Terrain-weather features include coordinate, slope, turning angle, weather condition, and road attribute, while spatio-temporal features consist of coordinate, the hour of day, and the day of week. The existing TTE models were trained on both datasets using these two categories of features as input, respectively. The rationalization of using terrain-weather features targeting plateaus and mountainous settings was validated by comparing the application results of the two categories of features.

-

A Transformer-based travel time estimation model for plateau and mountainous environments has been developed, drawing upon the MetaTTE model framework which has been frequently used in urban travel time estimation and has yielded satisfactory results15. In this model, Transformer is employed to substitute for LSTM in feature extraction. This choice was made because Transformer is capable of more flexibly handling input sequences of varying lengths, employing self-attention mechanisms to effectively capture long-distance dependencies16. Furthermore, studies have demonstrated that Transformer outperforms LSTM in managing long sequences and complex dependency tasks17,18,19,20. The model consists of Embedding Layer, Transformer Encoding Layer, and Decoding Layer. To effectively address long-range dependencies, we incorporated positional encoding and a multi-head self-attention mechanism within Transformer. This approach enables accurate predictions of travel time, particularly when dealing with a large number of trajectory points.

-

We have conducted a thorough validation and analysis of the performance of Transformer and LSTM structures based on the Meta-TTE model framework, respectively, utilizing experiments on plateau and mountain datasets. Our findings demonstrated that the Transformer model is more suitable for time estimation in plateau and mountainous regions.

Related works

Link-level estimation

Traditional travel time estimation methods usually divide a road into multiple segments, predict the travel time required for each individual segment, and then accumulate these times to obtain the total estimated travel time for the entire journey7,21. Generaly, many studies predict travel time at the link segment level by considering the characteristics of road segments. The characteristics of each link, including intersections, entrances/exits, and lanes, are combined with traffic volume data, event information, and other data to make real-time estimates. This enables the real-time provisioning of routes and the real-time management of specific segments, thereby achieving accurate time prediction. An early method in link-level estimation involves estimating the travel speed on individual road segments based on sensor readings from detectors22,23, which are then converted into travel time. However, this method requires large-scale sensor installation, which is costly and not conducive to widespread application. Due to the limitations of the speed estimation method in accurately predicting travel time, it is rarely used for this purpose nowadays. Petty et al.24 put forth a segmentation-based estimation method that arises from an intuitive stochastic model of traffic flow. This appraoch estimates link travel times directly from the single-trap loop detector flow and occupancy data, where the single-trap estimates of travel time can accurately track the true travel time through many degrees of congestion. Jenelius et al.25 present a statistical model for urban road network travel time estimation using vehicle trajectories obtained from low frequency (GPS) probes as observations. The network model separates trip travel times into link travel times and intersection delays. The observation model presents a way to estimate the parameters of the network model, including the correlation structure, through low frequency sampling of vehicle traces. The approach captures the underlying factors behind spatial and temporal variations in speeds, which is useful for traffic management, planning and forecasting.

The performance of the link-level time estimation method may be hindered by the inherent dynamics and uncertainties of the traffic system, which impede the ability to accurately predict the traffic conditions of road segments. This, in turn, affects the time estimation accuracy of each segment, resulting in a notable deviation in the overall time prediction due to the accumulation of errors.

Trajectory-level estimation

With the continuous development of deep learning technology and its widespread application in various fields22,23,26,27,28, deep learning has demonstrated strong capabilities in automatic feature extraction and generalization in addressing issues of time eitimation8,9. Simultaneously, the application of GPS devices provides us with a large amount of trajectory data29, thereby offering sufficient data support for the task of predicting travel times. Currently, more and more researchers are applying deep learning techniques to solve TTE problems30,31,32,33,34,35, using abundant trajectory data to train end-to-end TTE models, which can capture the correlations between complex input data and improve the estimation accuracy36,37,38,39. Compared to traditional methods, deep learning-based methods do not require segmenting the travel path and can directly predict the travel time required for a complete path. Bing et al.10 employed spatio-temporal graph convolutional networks to solve time series prediction problems for travel time estimation and obtained fast training with fewer parameters. Owing to the ability to memorize long-term time series information, Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) performs well in time series prediction, and many researchers have applied it to TTE models, achieving satisfactory prediction results. Now LSTM has become the mainstream structure of TTE models. Wang et al.11 proposed an end-to-end deep learning framework (i.e., DeepTTE) that combines convolution and LSTM to estimate the travel time of an entire path directly using features. The DeepTTE model is capable of capturing spatial correlations by geo-convolution operations in which the geographic information is integrated into the classical convolution. Furthmore, it also can capture the temporal dependencies by stacking the recurrent unit on the geo-convoluton layer. Zhang et al.12 put forward a bidirectional LSTM (BiLSTM) structure to extract additional backward information in addition to long-term and short-term features, with the aim of enhancing memory capability and improving time estimation accuracy. In light of the fact that the recurrent neural network (RNN), which is the most commonly used in travel time prediction, is prone to slow training and inference speed due to its structure being ill-suited to parallel computing, Sun et al.40put forth a novel, concise, and efficacious framework that is primarily based on feed-forward network (FFN), in which self-attention is employed to address multiple factors. This approach struck a favorable balance between inference speed and time prediction accuracy. Liu at al41proposed a new travel time estimation framework based on Transformer and Convolution Neural Networks (CNN) to improve the accuracy of travel time estimation, the model can effectively capture the spatial and temporal dependencies of the given trajectory at the same time. Lin at al42introduced the Periodic Transformer Encoder (PTE), PTE employs a streamlined encoder-only architecture that eliminates the need for a traditional decoder, thus significantly simplifying the model’s structure and reducing its computational demands, it is notably effective in adapting to high-variability road segments and peak traffic hours. Lin at al43 proposed the Periodic Stacked Transformer (PS-Transformer), a novel Transformer-based framework designed to enhance both short and long-term traffic predictions. PS-Transformer consists of two primary modules: the Segment Encoding Integration (SEI), which can extract periodic patterns from traffic data, and the Periodic Stacked Encoder-Decoder (PSED), which can effectively capture short-term and long-term dependencies from temporal attributes as well as tackle error accumulation.

Key features for travel time estimation

Presently, the existing travel time estimation methods are developed for urban contexts. The selection of features is based on the impact of traffic volume on travel time and is tailored to the specific urban traffic characteristics of each case. In the method proposed by Sun et al.40, the potential influence of traffic volume on travel time estimates is taken into account. Additionally, the possible impact of varying driver proficiency and travel patterns on travel time is considered. Consequently, three factors—driverID, the day of week, and departure time slice—are employed as features to predict travel time in this approach. Wang et al.11 considered the impact of weather conditions (rain, sunshine, wind, etc.) in addition to the impact of traffic volume on travel time, thereby enhancing the accuracy of urban regional travel time estimation. Sheng et al.44 considered the impact of traffic volume and congestion on the travel time. Concretely, the trajectory (a sequence of GPS points), urban congestion, taxi flow, passenger state, departure time, and travel date are chosen as input features to improve the accuracy of the model. Zhang et al.12 evaluated the influence of diverse road attributes (e.g., main road/highway) in conjunction with the impact of common features (e.g., peak and off-peak hours) on travel time. The driving state features corresponding to road attributes were defined by dividing the driving process into three stages: the starting stage, the middle stage and the ending stage. This allowed for the identification of differences in driving characteristics between the various stages. The incorporation of these features enhanced the accuracy of time estimation when road attributes were taken into account.

It can be observed that, despite the specific forms and quantities of features selected in different urban travel time prediction methods, each method contains features that reflect traffic volume from different perspectives.

Materials and methods

Dataset

Trajectory dataset

Plateaus are flat topographic units formed by tectonic uplift, usually at altitudes greater than 500 m, and mountains are terrain with significant heights and slopes45. We selected two areas from eligible plateau and mountainous regions in western China, respectively, and recorded vehicle trajectory data from March 2023 to February 2024 to construct datasets. The boundary information pertaining to the four regions is presented in Table 1.The database is constituted of trajectory point data pertaining to all driving trajectories. The trajectory point data comprises GPS coordinates and other pertinent information at the current location of the trajectory. The coordinates of the trajectory points are obtained through the recording of GPS coordinates at 2–4 s intervals during driving. The dataset comprises a number of features, including the hour of day and the day of week in addition to the coordinate, slope, turning angle, weather condition, and road attribute at each trajectory point.

-

Slope: It is used to describe the degree of steepness of a surface unit on the road at the trajectory point. This feature is particularly prevalent in wild areas characterized by plateaus and mountainous topography. It frequently influences the driving speed, consequently affecting the travel time.

-

Turning angle: It is defined as the angle of change in direction of the road at the trajectory point. A change in road direction typically results in a reduction in vehicle speed, particularly in instances of sharp turns. This contributes to an overall increase in travel time, and therefore the turning angle is regarded as a determining factor in travel time. This feature is usually manifested as various intersections of roads in urban areas, and bends and forks of roads in wild areas.

-

Weather condition: It refers to the various meteorological states (such as rainy, snowy, cloudy and sunny, etc.) during driving and their changes within a specific area where the trajectory point is located over a relatively short period of time. Adverse weather conditions frequently lead to significant inconvenience for driving and an overall increase in travel times. Especially in wild areas, severe weather may also deteriorate the accessibility of road networks and seriously affect traveling. The weather conditions were classified into fifteen specific categories in this study, including sunny, overcast, cloudy, light rain, moderate rain, heavy rain, T-storms, mist, thick mist, light snow, moderate snow, heavy snow, sleet, strong winds, and hail.

-

Road attribute: It is used to describe the quality of the road surface, as well as the traffic quality and the driving comfort afforded by different road surface qualities. The driving speed will be affected to a certain extent by this feature. Road attributes were classified into three specific categories, including paved-road, unpaved-road, and off-road, in this study.

-

The hour of day: It refers to a specific time of day (e.g. 8:00, 15:00, etc.). There are notable differences in traffic volume at different times of the day. During the morning and evening peak hours, the traffic volume is typically high, which often results in road congestion and impacts traffic efficiency. The traffic problem reflected by this feature is particularly prevalent in urban areas and almost absent in wild areas.

-

The day of week: It is used to denote a specific day of the week (e.g. Monday, Tuesday). There are notable differences in traffic volume on weekdays and weekends. This feature is also typically used for urban areas.

According to the definition of trajectory point, a record of a trajectory point in the dataset is described as the instance illustrated in Table 2.

We defined two categories of features: terrain-weather features and spatio-temporal features. These categories are based on the definitions of the features and their varying impacts on traffic conditions in urban and wilderness areas. Terrain-weather features include coordinate, slope, turning angle, weather condition, and road attribute, which provide a more accurate reflection of the actual factors influencing traffic conditions in wilderness environments. The remaining category comprises coordinate, the hour of day, and the day of week, which are frequently employed in travel time estimates in urban settings.

Calculation of slope

Using the Digital Elevation Model (DEM) data of the four specified experimental areas, we calculated the slope of the terrain corresponding to each DEM grid and determined the correspondence between the DEM grids and the trajectory points. The slope of a grid was regarded as that of its corresponding trajectory point. In this paper, the DEM data are described using a regular rectangular grid.

We used the planar method to calculate the slope46. The DEM data were projected in the elevation direction to obtain a 2D projection plane, and a 2D Cartesian coordinate system (i.e., xoy) of a 2D grid was established in this plane, where x and y represent the grid coordinates of the elevation data in the plane, which are consistent with the coordinates of the corresponding trajectory point. The slope of the terrain at a grid point was described using the maximum rate of change in elevation in each direction of the adjacent grids in the projection plane. Specifically, a 3 × 3 grid window was used for the calculation, as shown in Fig. 1. The slope of the central grid point (i.e. e) depends on the rate of elevation change in the horizontal direction (i.e., dz/dx) and vertical direction (i.e., dz/dy) in the projection plane, starting from e, where z represents the elevation value. The slope is calculated using Eq. (1).

Where π is the value of Pi, approximately 3.14. The elevation change rates in the x and y directions are calculated as follows:

Here, x_cellsize and y_cellsize represent the sizes of a grid in the x and y directions, respectively, both standardized to 0.5m in this study. The variables wight1, wight2, wight3, and wight4 denote the weights assigned to the neighboring grids of e in the horizontal and vertical orientations.

A weight of 1 is assigned to a grid with a valid elevation value, and 0 otherwise. To compute slope values at a specific grid point, a minimum of 7 out of its 8 neighboring grids must possess valid elevation values. For instance, if grids c, f, and i have valid elevation values (e.g., zc, zf, and zi), the calculation for wight1 is (1 + 2 × 1 + 1) = 4. Slope values for the boundary grids of the 2D projection are designated as NoData due to insufficient valid adjacent grids. Example of slope calculation is shown in Fig. 2.

Example of slope calculation. The values in the left-hand grids indicate the elevations of the corresponding grids, while the colored grid does not have a valid elevation value. In the right-hand grids, the data represent the slope values of the corresponding grids in the left-hand grids. The gray grids denote boundary grids without slope values and are labeled as NoData.

Calculation of turning angle

The turning angle of the first and last trajectory points was set to 0. For intermediate trajectory points, the turning angle can be calculated using the current trajectory point and its two adjacent trajectory points. As shown in Fig. 3, A(x1, y1), B(x2, y2), and C(x3, y3) are three consecutive trajectory points with GPS coordinates, where A and C are the adjacent points before and after B, respectively. To calculate the turning angle at point B, the direction angles of line segments AB and BC must first be calculated. The direction angle is the angle measured clockwise from north to south and is calculated using the arctangent function.

The direction angles of line segments AB and BC, denoted as θ1 and θ2, are determined through the following calculation:

The turning angle at point B, denoted as α, is calculated as the difference between the direction angles of the two line segments.

Dataset construction

The plateau region dataset comprises 21,896 data groups, encompassing 1558,000 trajectory points. The mountainous region dataset comprises 31,785 data groups, encompassing 1,971,000 trajectory points. In both regional datasets, each trajectory point is recorded with the following variables: coordinate, slope, turning angle, weather condition, road attribute, the hour of day, and the day of week. The travel time was set as the data label. The datasets were divided into training, validation, and test sets in a 6:2:2 ratio.

Transformer-based travel time estimation model

Overall structure

It is important to recognize that the conditions for estimating travel time in plateau and mountainous environments are not identical. Conventional approaches typically entail training models on two distinct datasets, one for the plateau region and the other for the mountainous region. This methodology allows for learning features and patterns that are pertinent to a specific environment during training. This resulted in the trained model being only applicable to an environment corresponding to the training set, which limited its generalization ability.

Meta-learning can help a model leverage the experience from the previous task on a new one, thereby allowing it to learn the shared features and patterns of both tasks, thus improving the model’s generalization ability and enabling it to quickly adapt to different environments and tasks. Accordingly, the Reptile algorithm47 in meta-learning was employed to train the model in this study to make the TTE model adaptable to tasks in both plateau and mountainous settings.

The basic process is as follows.

(1) Initialize model parameters.

(2) Randomly select one from both datasets for iterative training, complete model training for the current task, update and save the model parameters.

(3) Using the acquired model parameters as initial parameters, repeat step (2), until the preset training times on two datasets are satisfied.

Step (2) and step (3) are referred to as inner and outer loops, respectively, and each plays a distinct role in the meta-learning process.

(1) Inner loop: The model is updated several times on the randomly selected training dataset for a specific task, after which it completes the model training on the current dataset and learns the specific features of the task. The primary goal is to allow the model to learn quickly and adapt to the current task with a small amount of training data. The random selection of datasets ensures that the model does not bias toward any single dataset, thereby performing well in both plateau and mountainous environments.

(2) Outer loop: The outer loop globally optimizes the model across multiple tasks, during which the model parameters are globally optimized based on the inner loop updates of all tasks. The primary objective is to find a model with well-initialized parameters that can be adaptable to all tasks, thereby improving the model’s generalization ability and enabling it to quickly adapt to new tasks.

Using the meta-learning training strategy, the model is alternately trained on datasets from the two different environments, enabling the model to learn more diverse features and effectively estimate the travel time in both plateau and mountainous settings.

The proposed meta-learning training framework is illustrated in Fig. 4. This framework comprises plateau and mountainous datasets, ETD (Embedding Layer-Transformer Encoding Layer-Decoding Layer) models, and loss functions.

In each outer loop (i.e., one inner loop) of the meta-learning framework, a dataset is randomly selected from the two available datasets, and the ETD is trained by minimizing the loss function. The Adam algorithm48 is utilized as the optimizer, with mean absolute error (MAE) selected as the loss function. After K iterations of training, during which a batch of data is chosen as the input for each iteration, the ETD model parameters are updated. These updated parameters serve as the initial parameters for the subsequent outer loop, thereby completing the current inner loop, which represents a specific task. For each outer loop, the initial model parameters are denoted as θ1, the parameters optimized after K iterations in the inner loop are denoted as θ2, and the final model parameters, denoted as θf, of the current inner loop are updated in accordance with Eq. (7).

where r represents the current outer loop iteration, η denotes the maximum number of outer loop iterations, and β is the outer loop learning rate, which is also referred to as the step size.

As described in Zhou et al.15, the MetaTTE model framework consists of Embedding Layer, Encoding Layer, and Decoding Layer. The ETD model employs the same framework as MetaTTE, with the distinction that it utilizes Transformer for feature extraction in Encoding Layer. Consequently, the ETD model comprises three primary components: Embedding Layer, Transformer Encoding Layer, and Decoding Layer. The overall structure of ETD is illustrated in Fig. 5. The input data are transformed into feature vectors in Embedding Layer, followed by encoding in Transformer Encoding Layer. In Decoding Layer, the encoded features are initially combined using the self-attention mechanism and are subsequently decoded through the residual fully connected layers. Ultimately, the estimation of travel time is derived from the decoded feature representation.

Embedding layer

Embedding Layer facilitates the conversion of the discrete values of the slope, turning angle, weather condition, and road attribute at each trajectory point in the path into fixed-dimensional vectors. This ensures that the input and output dimensions are consistent in Transformer Encoding Layer, thereby avoiding complex dimension transformations. Furthermore, during the training process, the embedding vectors are continuously adjusted by the gradient descent algorithm with the objective of minimizing the distance between similar data points and maximizing that between dissimilar data points in the embedding space. This guarantees that the embedding vectors accurately reflect the relationships between data points, thus facilitating the model’s ability to discern intrinsic characteristics of the input data, thereby enhancing the feature learning efficiency.

The factors including slope, turning angle, weather condition, and road attribute at each trajectory point are initially represented using one-hot encoding49 as categorical values, denoted as c∈[C], C represents the high-dimensional space where the categorical values are located. Subsequently, the discrete categorical values in the sparse high-dimensional space C are transformed into the low-dimensional continuous vector space RE × 1 by the multiplication with a trainable parameter matrix W ∈ RC × Eusing a word embedding technique50. The embedding vectors have a dimension of 256, which ensures adequate expressive capability while maintaining relatively low computational and memory demands. The embedding vectors for each factor are obtained using Eq. (8).

where ∅(⋅) denotes the mapping function used for one-hot encoding, x represents the factor vector of slope, turning angle, weather condition, and road attribute, and z is the embedding vector. T stands for matrix transpose.

During the training process, parameters within matrix W are adjusted using a gradient descent algorithm to optimize the embedding space. In the case of GPS coordinates, the differences between each pair of coordinates (e.g., ∆p1, ∆p2), are used because they explicitly reflect the relationship between distance and travel time. Consequently, these differences (∆p1, ∆p2) serve as direct inputs to Transformer Encoding Layer, without the additional processes of one-hot encoding and word embedding conversion Embedding Layer. Given that coordinate data are represented using the differences between the coordinates of consecutive trajectory points, the number of channels for coordinate factors input into Transformer Encoding Layer is N = n − 1, where n represents the total number of trajectory points. In addition, the information of slope, turning angle, weather condition, and road attribute is one-hot encoded starting from the second trajectory point to ensure consistency in the number of feature channels.

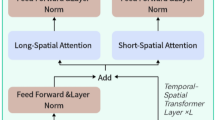

Transformer encoding layer

First, the embedding vectors derived from Embedding Layer representing the coordinate, slope, turning angle, weather condition, and road attribute undergo positional encoding, with the maximum length of the positional encoding set to 10,000 in this study. Subsequently, a Transformer encoder is employed to extract features. The encoder comprises a stack of two identical layers, each containing two sublayers: the multi-head self-attention mechanism and a position-wise fully connected feedforward network. A residual connection is applied around each of the two sublayers, followed by layer normalization. In this study, six Transformer structures were empolyed in the Transformer Encoding Layer, as illustrated in Fig. 6. This structure allows the encoder to capture dependencies across all positions in the input sequence.

In the multi-head self-attention mechanism, each head calculates self-attention independently. The ultimate representation vector, which consolidates diverse relationships and features identified by distinct attention heads, is derived through concurrent computation.

The output of the attention head is expressed as follows:

where i denotes the ith header. q, K, and V represent the Query (Q), Key (K), and Value (V) matrices, respectively. It is specified that dK= dv= dmodel/h. \(\:{W}_{i}^{Q}\) ∈\(\:{\varvec{R}}^{{d}_{model}\times\:{d}_{v}}\), \(\:{W}_{i}^{K}\) ∈\(\:{\varvec{R}}^{{d}_{model}\times\:{d}_{k}}\), and \(\:{W}_{i}^{V}\) ∈\(\:{\varvec{R}}^{{d}_{model}\times\:{d}_{V}}\) are the trainable parameter matrices corresponding to the query, key, and value of the ith head. Here, dmodel represents the dimension of input and output vectors in Transformer Encoding Layer, with a specific value of 256 in this study. Additionally, dk denotes the dimension of Q and K, dv represents the dimension of V, and h stands for the number of attention heads, which is set to 8 in the present research. Selecting eight attention heads achieves a balance between capturing comprehensive information and minimizing redundancy. An excessive number of heads can result in duplicated computations, whereas an insufficient number of heads may fail to capture sufficient information.

The calculation of self-attention is as follows:

The ultimate outcome of the multi-head attention mechanism is obtained when the outputs of the h attention heads are concatenated using Eq. (11).

where WO ∈ \(\:{\varvec{R}}^{h{d}_{v}\times\:{d}_{model}}\) is the linear transformation matrix used for concatenation.

The outcome of the multi-head self-attention mechanism undergoes further processing via residual connection and layer normalization prior to being fed into the feedforward neural network, thereby augmenting the model’s expressive power. This layer-by-layer sequential feature extraction process effectively captures high-level semantics and dependencies in the input sequence. The processing step is represented by Equation. (12).

Where x denotes the input matrix and represents the input data. W1∈\(\:{\varvec{R}}^{{d}_{model}\times\:{d}_{ff}}\) represents the weight matrix responsible for the initial linear transformation within the feedforward network, wherein x is transformed into a high-dimensional space with dimension dff. b1 represents the bias vector associated with the first layer, which also possesses dimension dff.

The output undergoes a non-linear transformation using the ReLU activation function. W2∈\(\:{\varvec{R}}^{{d}_{ff}\times\:{d}_{model}}\) represents the weight matrix responsible for the second linear transformation, which adjusts the dimension of the output matrix from the first layer back to the original dimension dmodel, thereby maintaining consistency in the dimensions of both inputs and outputs. In addition, b2 denotes the bias vector of the second layer, with a dimension of dmodel. In this study, dmodel was set to 256, and dff was set to 512. Subsequently, residual connection and layer normalization are applied to obtain the encoded results.

Decoding layer

Decoding Layer is responsible for transforming the high-dimensional feature representations produced by the encoding layer into the ultimate prediction outcomes. Initially, self-attention mechanisms are employed to merge the four categories of features associated with coordinate, slope, turning angle, weather condition, and road attribute, thereby capturing the intricate relationships and interdependencies among diverse features. Subsequently, the fused features are decoded through residual fully connected networks (FCNs) to obtain the travel time.

The matrices corresponding to the four feature categories are concatenated in the following manner:

Here, Xc, Xs, Xa, Xw, and Xr∈\(\:{\varvec{R}}^{N\times\:{d}_{model}}\) represent the encoded feature matrices for coordinate, slope, turning angle, weather condition, and road attribute, respectively, where N refers to the number of feature channels.

During the fusion process, the attention mechanism allocates distinct attention scores to various dimensions of each feature using a fully connected layer, as described in Eq. (14).

Here, H represents the attention scores for each dimension of each feature, W∈RN×F×F is the trainable parameter matrix, where F denotes the number of features, which is set to 5 in this case, and b is the bias vector with a dimension of dmodel.

The attention scores for the ith feature (e.g., Hi), undergo normalization using Softmax to obtain the attention weight for each dimension according to Eq. (15).

Where ai denotes the attention weight.

The fused feature representation Xf∈\(\:{\varvec{R}}^{N\times\:{d}_{model}}\) is obtained from Eq. (16) using the attention weights.

Where F represents the number of categories of features.

Subsequently, the fused features are decoded using residual fully connected layers (FCs)51. The integration of the nonlinear transformations of the FCs with the information retention properties of the residual connections enhances the model’s capacity to capture intricate dependencies within long sequences, thereby augmenting the decoding accuracy and efficacy. A residual block is constructed using four FCs, and the ultimate prediction outcome is derived from the fully connected layer that succeeds the residual block. The process is delineated as follows:

Where Wi represents the trainable matrix of the ith fully connected layer. FCi represents the ith fully connected layer. The number of units in the four residual fully connected layers was set to 1024, 512, 256, and 256, respectively.

Results

Experimental setup

The training was conducted on a single NVIDIA RTX 4090 GPU, using the plateau and mountainous datasets for training, validation, and testing. The meta-learning training was performed with a maximum iteration number of η = 100 for outer loops, an outer loop learning rate of β = 0.1, and an inner loop iteration number of K = 10. The Adam optimiser was employed with an inner loop learning rate of lr = 0.01, a learning rate decay(LDR) of lr_reduce = 0.5, and a batch size of 32.

Evaluation metrics

In the estimation of travel times, the mean absolute error (MAE), mean absolute percentage error (MAPE), and root mean square error (RMSE) are frequently employed as evaluation metrics for comprehensive analysis of model errors and assessment of model performance.

MAE quantifies the average magnitude of errors in a given prediction set. It directly reflects the average discrepancy between the predicted and actual values, where all individual differences are equally weighted.

Where n refers to the number of values, represents the actural value, and represents the predicted value.

MAPE measures the magnitude of the error expressed as a percentage. The value is calculated as the average of the absolute percentage errors of the predictions, which facilitates comparisons between different datasets.

RMSE measures the average magnitude of the error using a quadratic scoring rule. The value is the square root of the average of the squared differences between the actual and predicted values. The RMSE assigns greater weight to larger errors.

Experimentation and analysis

Comparison of experimental results with different input features

Zhou et al.15 proposed five models with different structures, i.e., MetaTTE-WT, which utilizes LSTM as the encoding layer without short-term and long-term embeddings, MetaTTE-WA, which utilizes LSTM as the encoding layer without attention-based fusion, MetaTTE-LSTM, MetaTTE-BiLSTM, and MetaTTE-GRU, which utilizes Gated Recurrent Unit as the encoding layer. All models were trained with the meta-learning framework and demonstrated superior performance in urban environments compared to other models. We utilized the spatio-temporal features and terrain-weather features from both plateau and mountainous datasets to train, validate, and test these five models, along with our model that employs the same framework as these models, respectively. We then evaluated their performance.

Tables 3 and 4 present the experimental findings of the five models using two different types of input features from the plateau and mountainous datasets, respectively. On the plateau dataset, the application of terrain-weather features resulted in an average decrease of 44.52% in MAE, 43.51% in MAPE, and 40.50% in RMSE across the five models compared to the use of spatio-temporal features. Similarly, on the mountainous dataset, MAE decreased by 41.59%, MAPE decreased by 44.57%, and RMSE decreased by 43.58%, on average.

The histograms in Figs. 7 and 8, which provide a visual representation of the experimental results, also illustrate that substituting spatio-temporal features with terrain-weather features as input features lead to a notable decrease in MAE, MAPE, and RMSE of the five models. This observation suggests that terrain-weather features are likely more suitable for travel time estimation in plateau and mountainous areas.

Comparison of model performance

The experimental results are presented in Table 5. Our model demonstrated the most favorable results in terms of MAE, MAPE, and RMSE on both datasets. Compared with the lowest values of each corresponding metric of the five models, the MAE, MAPE, and RMSE values on the plateau dataset were reduced by 13.52%, 14.89%, and 14.05%, respectively. Similarly, on the mountainous dataset, the MAE, MAPE, and RMSE values decreased by 9.72%, 12.20%, and 11.40%, respectively.

The histograms presented in Figs. 9 and 10 provide a visual representation of the experimental outcomes of the models on both datasets. The results demonstrate that the proposed model exhibits superior time estimation accuracy compared to other models on both datasets. This indicates that our model outperformed the other models in plateau and mountainous settings.

Discussion

The experimental results presented in Tables 3 and 4; Fig. 7, and Fig. 8 illustrate a notable improvement in the accuracy of travel time estimation across the six models who have the same framework when using terrain-weather features as input compared to spatio-temporal features, even though the first five models were originally developed for urban travel time estimation. According to previous definitions of these features, the terrain-weather features typically exert a greater influence on traffic in wilderness environments. For instance, roads in wilderness areas, particularly in plateau and mountainous regions, often exhibit varying gradients and curves, which complicate driving conditions compared to the relatively flat and uniform roads found in urban areas. This complexity results in a more significant impact on traffic in wilderness settings. Conversely, spatio-temporal features tend to have a more pronounced effect on urban traffic. For example, traffic volume in urban areas experiences considerable fluctuations at different times, especially during peak hours. These fluctuations frequently lead to traffic congestion, a phenomenon that is less common in wilderness areas and can often be disregarded in terms of its impact on traffic. When utilizing datasets based on plateau and mountainous environments for time prediction, predictions derived from terrain-weather features are more effective than those based on spatio-temporal features, as the former are more closely aligned with the traffic conditions in these regions. Based on the analysis presented above, we conclude that the spatio-temporal features typically utilized as input features in travel time estimation models for urban environments are not suitable for application in wild environments.

Another important point to clarify is that, in urban settings, various traffic information provided by the traffic management system—such as traffic signals, signs, and intersections—can be utilized to enhance the accuracy of travel time predictions. However, in wilderness environments, such information is nearly nonexistent, and only natural factors, such as terrain and weather conditions, can be relied upon for estimating travel time. This reliance on limited data increases the difficulty of time prediction and adversely affects the accuracy of the results. Accordingly, the accuracy of travel time estimates in wilderness settings is not yet on a par with that achieved by the prevailing methods in urban areas, as demonstrated by the findings of our study and application.

The experimental findings presented in Table 5; Fig. 9, and Fig. 10demonstrate the superior performance of the proposed model compared to the five benchmark models15. Table 6provides an overview of the structural attributes of all models, all of the five benchmark models, namely MetaTTE-WT, MetaTTE-WA, MetaTTE-LSTM, MetaTTE-BiLSTM, and MetaTTE-GRU, utilize LSTM or its variants (i.e., BiLSTM, GRU) for feature extraction. LSTM regulates the flow of information through a gate mechanism comprising input, forget, and output gates, which enables the effective capture of long-term dependencies. However, when handling long sequences of data, the input information at each time step tends to be progressively diluted or overwritten during multiple updates, leading to information decay52. Consequently, this phenomenon impairs the precision of the model in capturing long-distance scale information.

As mentioned above, in contrast to the time estimation methods typically employed for urban areas, accurately predicting travel time in plateau and mountainous settings necessitates the processing of longer sequences of data, which contain a greater number of long-term dependencies. It is evident that the five benchmark models, developed using LSTM, exhibit inferior performance compared to the Transformer model on plateau and mountainous datasets. This is attributed to the reduced accuracy of LSTMs, which is caused by information decay when processing long sequences.

Unlike the previously mentioned methods, the model proposed in this study employs the Transformer architecture to extract features, relying on the multi-head self-attention mechanism to process sequences of data. The self-attention mechanism facilitates the computation of relationships between each position and all other positions, thereby establishing global dependencies. This allows the model to simultaneously focus on all positions within the entire sequence, without being constrained by sequence length. Such a method of processing global information enables the model to effectively capture long-distance dependencies in trajectory data, ensuring that information is preserved as the time steps increase, thus preventing information decay. This characteristic is particularly beneficial for achieving more accurate travel time estimates in complex environments, resulting in superior travel time estimation performance of Transformer compared to LSTM. This renders the transformer structure particularly advantageous in scenarios where the number of trajectory points necessary for complex terrain increases, thereby enhancing the model’s practicality and generalization capabilities in travel time estimation in challenging terrains.

MetaTTE-BiLSTM uses Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory (BiLSTM) for feature extraction, in which two LSTM layers, i.e., the forward (from front to back) layer and the backward (from back to front) layer, are combined to employ both past and future information simultaneously, making it more capable than LSTM in capturing sequence dependencies. MetaTTE-GRU uses the Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU) for feature extraction, which features only reset and update gates, thereby simplifying the structure. Generally, it converges faster during training, which helps obtain more optimized model parameters within a limited training period, thereby improving model performance. Therefore, both MetaTTE-BiLSTM and MetaTTE-GRU outperformed MetaTTE-LSTM for travel time estimation in plateau and mountainous environments, as demonstrated by the experimental results.

The MetaTTE-LSTM, MetaTTE-BiLSTM, MetaTTE-GRU, and our proposed model all employ word embedding for feature embedding and self-attention mechanisms for feature fusion. Using word embeddings enables the capture of intricate relationships between features, which enriches feature representations. This allows the model to learn the interrelationships between these features effectively, ultimately improving prediction accuracy.The use of the self-attention mechanism for feature fusion allows for comprehensive information integration from multiple data sources, capturing intricate dependencies, and flexibly assigning weights to each feature in accordance with the relative importance of the features derived from Encoding Layer. This allows the model to adaptively prioritize the most pertinent information when fusing features, which enhances predictive performance. In contrast to the other models, MetaTTE-WT does not employ the self-attention mechanism for feature fusion in Decoding Layer, whereas MetaTTE-WA does not use word embedding for feature embedding. Consequently, these two models are less effective than others when predicting the travel time in plateau and mountainous settings.

Conclusions

Most existing vehicle travel time estimation methods have been developed for urban environments. This paper proposed a methodology that applies to the wilderness, with a particular focus on plateau and mountainous regions.

In consideration of the driving conditions typically encountered in wilderness areas, particularly in regions characterized by plateau and mountainous topography, a set of terrain-weather features, which comprise the coordinate, slope, turning angle, weather condition, and road attribute, was meticulously crafted to accurately depict the actual driving conditions experienced in wilderness environments. Consequently, these features demonstrate exceptional efficacy in predicting travel time in such environments. It is notable that even the currently available urban travel time estimation models yield more precise estimations when applied to plateau and mountainous datasets. This highlights the superior suitability of these features for travel time estimation in wilderness environments, especially in plateau and mountainous settings, compared to the spatio-temporal features typically employed in urban areas. Furthermore, the travel time estimation model based on Transformer benefits from the integration of positional encoding and the multi-head self-attention mechanism, which enhances its capability to effectively capture long-distance dependencies. Therefore, it enables precise travel time estimation, particularly when managing extensive trajectory points. This model notably enhances the estimation precision in plateau and mountainous settings, thereby mitigating the reduced accuracy of current LSTM-based approaches when faced with long sequence inputs. This suggests that the Transformer-based model outperforms the LSTM-based model in estimating travel time in wilderness environments, even when using the same model framework. In addition, the meta-learning strategy employed in this study improves the generalization ability of the proposed model, thereby ensuring its suitability for accurate travel time estimation in more diverse challenging settings.

However, the proposed model requires further optimization to reduce complexity to meet real-time navigation requirements. It is therefore recommended that future efforts should prioritize model lightweighting. Additionally, the principal objective of this study was to develop travel time estimation methods that are applicable in plateau and mountainous settings. To enhance the accuracy of time predictions and the broad applicability of estimation methods, it is essential to conduct a more comprehensive analysis of the factors that influence time estimation in diverse environments (e.g., deserts, grasslands, etc.), thereby facilitating the development of travel time estimation solutions applicable to a wider range of environments.

Data availability

The datasets used and analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Liu, H., Jin, C. & Zhou, A. Popular route planning with travel cost estimation from trajectories. Front. Comput. Sci. 14, 191–207. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11704-018-7249-z (2020).

Amirian, P., Basiri, A. & Morley, J. in Proceedings of the 9th ACM SIGSPATIAL International Workshop on Computational Transportation Science 31–36 (2016).

Hu, X., Chen, L., Tang, B., Cao, D. & He, H. Dynamic path planning for autonomous driving on various roads with avoidance of static and moving obstacles. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 100, 482–500. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymssp.2017.07.019 (2018).

Zhang, H. et al. Knowledge distillation for Travel Time Estimation. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. https://doi.org/10.1109/tits.2024.3374325 (2024).

Wu, Y., Chen, F., Lu, C. & Yang, S. Urban traffic flow prediction using a spatio-temporal random effects model. 20, 282–293, (2016). https://doi.org/10.1080/15472450.2015.1072050

Zheng, Z., Ye, Y., Zhu, Y., Zhang, S. & Yu, J. J. Q. Data-Driven Methods for Travel Time Estimation: A Survey. In IEEE 26th International Conference on Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITSC). 1292–1299. (2023).

Mori, U., Mendiburu, A., Álvarez, M. & Lozano, J. A. A review of travel time estimation and forecasting for advanced traveller information systems. Transportmetrica A: Transp. Sci. 11, 119–157. https://doi.org/10.1080/23249935.2014.932469 (2015).

Zhou, K. et al. Domain generalization: a survey. 45, 4396–4415 (2022).

Zebari, R., Abdulazeez, A., Zeebaree, D., Zebari, D. & Saeed, J. A. Comprehensive Review of Dimensionality reduction techniques for feature selection and feature extraction. J. Appl. Sci. Technol. Trends. 1, 56–70. https://doi.org/10.38094/jastt1224 (2020).

Yu, B., Yin, H. & Zhu, Z. Spatio-temporal graph convolutional networks: a deep learning framework for traffic forecasting. arXiv https://doi.org/10.24963/ijcai.2018/505 (2017). arXiv:1709.04875, doi.

Wang, D., Zhang, J., Cao, W., Li, J. & Zheng, Y. When will you arrive? estimating travel time based on deep neural networks. In Proceedings of the AAAI conference on artificial intelligence.

Zhang, H., Wu, H., Sun, W. & Zheng, B. Deeptravel: a neural network based travel time estimation model with auxiliary supervision. arXiv https://doi.org/10.24963/ijcai.2018/508 (2018). arXiv:1802.02147, doi.

Hochreiter, S. & Schmidhuber, J. Long short-term memory. Neural Comput. 8, 1735–1780. https://doi.org/10.1162/neco.1997.9.8.1735 (1997).

Lipton, Z. C., Berkowitz, J. & Elkan, C. A critical review of recurrent neural networks for sequence learning. arXiv arXiv:1506.00019, doi:https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1506.00019

Wang, C. et al. Fine-grained trajectory-based travel time estimation for multi-city scenarios based on deep meta-learning. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 23, 15716–15728. https://doi.org/10.1109/tits.2022.3145382 (2022).

Vaswani, A. et al. Attention is all you need. Adv. Neural. Inf. Process. Syst. 30 https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1706.03762 (2017).

Yang, Z. et al. Xlnet: generalized autoregressive pretraining for language understanding. Adv. Neural. Inf. Process. Syst. 32 https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1906.08237 (2019).

Lee, J. & Toutanova, K. Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. arXiv arXiv:04805 (2018).

Wang, Y. et al. Transformer-based acoustic modeling for hybrid speech recognition. In ICASSP 2020–2020 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP). 6874–6878 (IEEE).

Lim, B., Arık, S. Ö., Loeff, N. & Pfister, T. Temporal fusion transformers for interpretable multi-horizon time series forecasting. Int. J. Forecast. 37, 1748–1764. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijforecast.2021.03.012 (2021).

Wang, X. & Chen, X. Travel time estimation of a single segment based on freeway toll data. In CICTP 2014: Safe, Smart, and Sustainable Multimodal Transportation Systems. 2161–2174.

Lee, E. H. Traffic speed prediction of Urban Road Network based on high importance links using XGB and SHAP. IEEE Access. 11, 113217–113226. https://doi.org/10.1109/access.2023.3324035 (2023).

Min, J. H., Ham, S. W., Kim, D. K. & Lee, E. H. Deep Multimodal Learning for Traffic Speed Estimation combining dedicated short-range communication and vehicle detection System Data. Transp. Res. Record: J. Transp. Res. Board. 2677, 247–259. https://doi.org/10.1177/03611981221130026 (2022).

Petty, K. F. et al. Accurate estimation of travel times from single-loop detectors. Transp. Res. Part. A: Policy Pract. 32, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0965-8564(97)00015-3 (1998).

Jenelius, E. & Koutsopoulos, H. N. Travel time estimation for urban road networks using low frequency probe vehicle data. Transp. Res. Part. B: Methodological. 53, 64–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trb.2013.03.008 (2013).

Dong, S., Wang, P. & Abbas, K. A survey on deep learning and its applications. Comput. Sci. Rev. 40 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosrev.2021.100379 (2021).

Qu, G. et al. Road-MobileSeg: Lightweight and Accurate Road extraction model from Remote sensing images for Mobile devices. Sensors 24 https://doi.org/10.3390/s24020531 (2024).

Torres, J. F., Hadjout, D., Sebaa, A., Martínez-Álvarez, F. & Troncoso, A. Deep learning for time series forecasting: a survey. Big Data. 9, 3–21. https://doi.org/10.3390/forecast5010017 (2021).

Fan, J., Fu, C., Stewart, K. & Zhang, L. Using big GPS trajectory data analytics for vehicle miles traveled estimation. Transp. Res. Part. C: Emerg. Technol. 103, 298–307. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trc.2019.04.019 (2019).

Yuan, H., Li, G., Bao, Z. & Feng, L. in Proceedings of the ACM SIGMOD International Conference on Management of Data 2135–2149 (2020). (2020).

Tang, K., Chen, S., Khattak, A. J. & Pan, Y. Deep architecture for citywide travel time estimation incorporating contextual information. J. Intell. Transp. Syst. 25, 313–329. https://doi.org/10.1080/15472450.2019.1617141 (2021).

Tran, L. et al. DeepTRANS. Proc. VLDB Endow. 13, 2957–2960. https://doi.org/10.14778/3415478.3415518 (2020).

Abdollahi, M., Khaleghi, T. & Yang, K. An integrated feature learning approach using deep learning for travel time prediction. Expert Syst. Appl. 139 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2019.112864 (2020).

Serin, F., Alisan, Y. & Erturkler, M. Predicting bus travel time using machine learning methods with three-layer architecture. Measurement 198 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.measurement.2022.111403 (2022).

Lee, E. H., Kho, S. Y., Kim, D. K. & Cho, S. H. Travel time prediction using gated recurrent unit and spatio-temporal algorithm. In Proceedings of the institution of civil engineers-municipal engineer. 88–96 (Thomas Telford Ltd).

Wang, Z., Fu, K. & Ye, J. Learning to estimate the travel time. In Proceedings of the 24th ACM SIGKDD international conference on knowledge discovery & data mining. 858–866.

Han, L. et al. Multi-semantic path representation learning for travel time estimation. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 23, 13108–13117. https://doi.org/10.1109/tits.2021.3119887 (2021).

Hong, H. et al. HetETA: Heterogeneous information network embedding for estimating time of arrival. In Proceedings of the 26th ACM SIGKDD international conference on knowledge discovery & data mining. 2444–2454.

Qiu, J., Du, L., Zhang, D., Su, S. & Tian, Z. Nei-TTE: Intelligent traffic time estimation based on fine-grained time derivation of road segments for smart city. IEEE Trans. Industr. Inf. 16, 2659–2666. https://doi.org/10.1109/tii.2019.2943906 (2019).

Sun, Y. et al. FMA-ETA: Estimating travel time entirely based on FFN with attention. In ICASSP 2021–2021 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP). 3355–3359 (IEEE).

Liu, F., Yang, J., Li, M. & Wang, K. MCT-TTE: Travel Time Estimation based on transformer and convolution neural networks. Sci. Program. 2022 (3235717). https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/3235717 (2022).

Lin, H. T. C. & Tseng, V. S. J. E. Periodic Transformer Encoder for Multi-Horizon Travel Time Prediction. 13, 2094, (2024). https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics13112094

Lin, H. T., Dai, H. & Tseng, V. S. Periodic Stacked Transformer-based Framework for Travel Time Prediction. In 2024 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN). 1–8 (IEEE).

Sheng, Z. et al. Taxi travel time prediction based on fusion of traffic condition features. Comput. Electr. Eng. 105 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compeleceng.2022.108530 (2023).

Gerrard, J. Mountain Environments: An Examination of the Physical Geography of Mountains (MIT Press, 1990).

Burrough, P. A., McDonnell, R. A. & Lloyd, C. D. Principles of Geographical Information Systems (Oxford University Press, 2015).

Nichol, A., Achiam, J. & Schulman, J. On first-order meta-learning algorithms. arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1803.02999 (2018). arXiv:02999.

Kingma, D. P., Ba, J. & Adam A method for stochastic optimization. arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1412.6980 (2014). arXiv:1412.6980,.

Bishop, C. M. & Nasrabadi, N. M. Pattern Recognition and Machine Learning (Springer, 2006).

Bahdanau, D., Cho, K. & Bengio, Y. Neural machine translation by jointly learning to align and translate. arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1409.0473 (2014). arXiv:1409.0473, doi.

Rumelhart, D. E., Hinton, G. E. & Williams, R. J. Learning representations by back-propagating errors. nature 323, 533–536, (1986). https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/1888.003.0013

Chien, H. Y. S. et al. Slower is better: revisiting the forgetting mechanism in LSTM for slower information decay. arXiv arXiv:05944, doi:https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2105.05944 (2021).

Funding

This work was funded by the Identification and digital mapping of physical properties of the Martian surface, No.E2C1051700 and the Strategic Leading Science and Technology Project of CAS, No.XDA0430103.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Q.Z. and A.Z. conceived, designed and supervised the whole study. G.Q. and A.Z. were responsible for the original draft of the article. G.Q. developed the Transformer-based Travel Time Estimation model. R.W., D.L., Z.L. and D.Z. constructed database. Q.Z. and Y.L. conducted the writing-reviewing and editing. Q.Z. and K.Z. were responsible for resources, visualization and project administration. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Qu, G., Zhou, K., Wang, R. et al. Transformer-based travel time estimation method for plateau and mountainous environments. Sci Rep 15, 4235 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88626-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88626-9