Abstract

Whole-brain radiotherapy (WBRT) remains a standard treatment for extensive brain metastases, providing symptom relief and improved progression-free survival (PFS). Re-irradiation is often necessary for recurrent disease, particularly in the cerebellum, which accounts for 10–20% of cases. Cerebellar metastases are associated with distinct symptoms and poorer prognoses compared to supratentorial lesions. This study evaluates the outcomes of cerebellar-only re-irradiation for brain metastases, with or without stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) for supratentorial lesions. A retrospective analysis of 56 patients treated between 2017 and 2023 was conducted. Patients received cerebellar-only re-irradiation after WBRT. Symptom improvement was assessed three months post-treatment. Statistical analyses included t-tests, Mann-Whitney U tests, and multivariable logistic regression. The cohort’s median age was 53 years, with breast cancer being the most prevalent histology (71%). Symptom improvement occurred in 75% of patients, with relief rates of 84.6% for nausea, 80% for headache, and 58.3% for dizziness. Dexamethasone use decreased in 76.3% of cases. Median PFS was 39.2%, with a six-month overall survival of 50%. Only 1.7% of patients developed symptomatic radiation necrosis. Factors associated with symptom improvement included younger age, extended intervals between WBRT and re-irradiation, and higher equivalent dose in 2 Gy fractions (EQD2). Cerebellar-only re-irradiation is an effective, low-toxicity option for recurrent cerebellar metastases. This approach warrants further validation in prospective studies, particularly in comparison to SRS.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Whole-brain irradiation (WBRT) remains a treatment option and is indicated for many patients with brain metastases. Although WBRT does not improve overall survival (OS), it provides effective symptom relief in the majority of cases1,2. Hypofractionated stereotactic radiotherapies (SRTs), including stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS), have become the standard of care for patients with a limited number of brain metastases due to their ability to deliver precise, high-dose radiation while sparing normal tissue. However, for patients with extensive brain metastases who are not eligible for SRS or surgery, WBRT remains the first-line treatment3. For these patients, WBRT provides symptom relief and can prolong survival. Several studies have demonstrated that cancer patients with brain metastases experience an overall response rate of 75–85%, as measured by symptom improvement or stabilization, and achieve appreciable progression-free survival (PFS) after WBRT4.

Unfortunately, for some patients, disease progression necessitates re-irradiation. Re-WBRT may improve symptoms in cases of brain metastasis recurrence; however, it raises concerns about central nervous system toxicity, particularly cognitive decline5,6.

While most brain metastases occur in the supratentorial space, approximately 10–20% metastasize to the posterior fossa7. Cerebellar metastases are distinct from their supratentorial counterparts, often causing symptoms disproportionate to their size due to their location. These lesions can lead to obstructive hydrocephalus, brainstem compression, and herniation, resulting in acute neurological decline. The unique clinical behavior of cerebellar metastases, including their rapidly progressive symptoms and different risk profiles, warrants distinct treatment strategies and outcomes8. Patients with significant cerebellar disease also tend to have a poorer prognosis8,9.

In the context of recurrent brain metastases, SRS is often employed due to its precision and reduced toxicity compared to WBRT. However, its application in the cerebellum is challenging. The smaller volume of the posterior fossa and the proximity of multiple lesions to critical structures, such as the brainstem and fourth ventricle, increase the risk of delivering excessive doses to normal tissue. For patients with a high burden of cerebellar disease, SRS may not be feasible, and alternative approaches are necessary10.

Cerebellar-only re-irradiation offers a tailored approach to managing symptomatic cerebellar metastases, providing symptom relief while minimizing the risks associated with re-WBRT or SRS. This strategy may also facilitate response to systemic therapy or salvage radiosurgery for limited supra-tentorial lesions.

This study aimed to evaluate the outcomes of cerebellar-only re-irradiation, with or without focal stereotactic radiosurgery for supra-tentorial lesions, by conducting a retrospective analysis of cases from our institution.

Methods

Following institutional review board approval (0265-23-SMC), a retrospective review was conducted on patients undergoing re-irradiation between 2017 and 2023 for symptomatic brain metastases in the cerebellum following whole-brain radiotherapy (WBRT). Patients were included if a tumor board discussion recommended whole-cerebellum radiation instead of stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS), and a neurological examination was performed both before and after radiation. Cases with limited, asymptomatic supra-tentorial disease, which were treated with SRS, were included. Patients with diffuse leptomeningeal disease were excluded when the decision was to treat only the cerebellum.

Clinical, dosimetric, and outcome data were collected and analyzed. Symptom data were extracted from patients’ files before treatment and three months after cerebellar radiation. Both volumetric arc therapy (VMAT) and 3D radiation planning were included, as well as all dose regimens. Dose constraints for re-cerebellar RT were set at an EQD2 of 72 Gy cumulative (combining the first and second radiation courses), with a point maximum for the brainstem and as low as reasonably achievable (ALARA) constraints for the cochlea, as previously cited11,12.

Symptom assessment was conducted using chart reviews, and improvement in de-conditioning was determined based on reports from patients, caregivers, or physicians. Descriptive analyses were performed using means and standard deviations for parametric variables and medians with ranges for non-parametric variables. A t-test was used for parametric variables, while the Mann-Whitney U test was employed for non-parametric data. Counts were used for categorical variables, and chi-square tests were applied for statistical analysis. Variables impacting local control were assessed using multivariable logistic regression to calculate odds ratios. Variables were tested for high correlations before inclusion in the multivariable analysis.

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software (IBM, Chicago, USA, version 29). All cases were discussed in neuro-oncological tumor board meetings. In all instances, the progression of brain metastases was confirmed by MRI following the initial course of WBRT.

Results

This cohort consisted of 56 patients who underwent re-irradiation to the cerebellum following WBRT and had complete neurological reports both pre- and post-radiation, accounting for 87.5% of all cases reviewed. The median age was 53 years (range: 28–68), and the Karnofsky performance status ranged from 70 to 90. All patients exhibited cerebellar symptoms, which were categorized into six main domains: (1) gait dysfunction, (2) nausea and vomiting, (3) dysarthria, (4) movement disorder, (5) dizziness, and (6) headache.

Breast cancer was the most common histology, affecting 40 patients. Other histologies included small cell lung cancer (8), ovarian adenocarcinoma (4), non-small cell lung adenocarcinoma (3), and melanoma (1). The median interval between WBRT and cerebellar RT was 15 months (range: 8–25). WBRT techniques included 3D planning in 85% of cases and VMAT with hippocampal avoidance in 15%. Most patients (92%) received 30 Gy in 10 fractions during WBRT, while the remainder received 20 Gy in 5 fractions (Figs. 1, 2 and 3).

MRI T1 + contrast axial image 3 month after Radiotherapy showing Radiological response compare to Fig. 1.

Cerebellar RT was delivered using 3D and VMAT in 57.2% and 42.8% of the cohort, respectively. Systemic therapy was administered to 75% of patients during or before/after the RT course. Radiosurgery was performed for supra-tentorial lesions in 46% of patients after cerebellar RT, with a median of 5 lesions (range: 1–11) treated per patient. The median radiosurgery dose was 20 Gy (range: 16–24), delivered in single fractions.

The dose regimens for cerebellar RT were heterogeneous: 20 Gy in 10 fractions (21.4%), 25 Gy in 10 fractions (21.4%), 25 Gy in 5 fractions (17.8%), 24 Gy in 6 fractions (17.8%), 30 Gy in 12 fractions (10.7%), and 30 Gy in 10 fractions (10.7%). Table 1 shows a median follow-up duration of 14 months (range: 6–23). Symptomatic therapy with dexamethasone, at dosages ranging from 2 mg to 16 mg daily, was provided to 67.8% (38) of the cohort before the second RT course.

Clinical outcome

All patients presented with symptoms, with most exhibiting more than one domain of cerebellar syndrome. Neuro-oncologist evaluations reported symptomatic improvement in 75% (42) of patients, with a median time to improvement ranging from 2 to 8 months post-radiation. Among the remaining 25% (7 patients), 4 had stable neurological symptoms, while 3 experienced deterioration.

Of the 42 cases showing symptomatic improvement, 38 had cerebellar metastases only. The remaining 5 cases included patients with supra-tentorial lesions, 4 of whom had significant mass effect, causing motor weakness and aphasia. For these patients, radiosurgery was planned following cerebellar RT and was successfully administered. In 1 patient with minor supra-tentorial disease, the decision was made to treat only the cerebellum.

The most common symptom improvements were reported for nausea and vomiting, with 22 of 26 patients (84.6%) reporting relief. Improvements were observed for gait dysfunction in 8 of 20 patients (40%), dysarthria in 6 of 14 patients (42%), movement disorders in 10 of 18 patients (55%), dizziness in 14 of 24 patients (58.3%), and headache in 12 of 15 patients (80%).

Dexamethasone use decreased in 76.3% (29/38) of patients following RT. Among these, 89.8% (26/29) reduced dexamethasone due to symptomatic improvement.

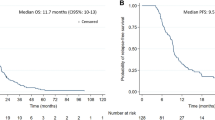

Radiological response correlated strongly with clinical outcomes, as 90% of patients with neurological improvement or stability showed radiological responses, while all patients with clinical deterioration exhibited radiological progression. Six-month overall survival from the start of re-irradiation was 50%, with progression-free survival at 39.2%.

Multivariable analysis identified significant factors associated with clinical improvement after re-irradiation: age < 50 years (OR: 0.56, CI 95%: 0.1–0.86, p = 0.023), time from initial RT > 8 months (OR: 0.67, CI 95%: 0.42–0.86, p = 0.034), and EQD2 > 30 Gy (OR: 0.67, CI 95%: 0.24–0.91, p = 0.042). Additional details are shown in Table 2.

Toxicity

Among the 56 patients who underwent re-irradiation to the cerebellum, only one developed symptomatic radiation necrosis (RN), representing 1.7% of the cohort. This patient was a 44-year-old woman diagnosed with breast cancer. She had previously received WBRT with a dose of 30 Gy in 10 fractions using a 3D technique.

Five months later, due to progressive symptomatic disease in the cerebellum, she received a second course of 25 Gy in 5 fractions using VMAT approach.

Five months following the second RT course, she presented with headaches and vomiting. Follow-up MRI revealed significant edema and a reduction in the size of the metastatic lesions. Multi-parametric MRI, including a TRAM sequence, suggested RN, which was confirmed in a tumor board discussion. Her dexamethasone dosage was increased to 16 mg twice daily, resulting in relief of her symptoms within three weeks. Unfortunately, despite symptomatic management, the patient succumbed to progressive systemic disease eight months after the second RT course.

In addition to the single case of symptomatic RN, there were five documented cases of radiographic radiation necrosis (9.09%) that were asymptomatic. These findings align with known risks of RN following re-irradiation, emphasizing the importance of careful dosimetric planning and monitoring.

Discussion

In this retrospective study, we aim to show that re-irradiation to the cerebellum is feasible and does have clinical benefits. Previous studies have shown that there have been a limited number of articles in the literature describing re-WBRT with acceptable toxicities, minimal side effects, and a treatment that provides symptomatic relief5,11. Over the years, radiation oncologists have become more generous when indicating a second course of WBRT, especially in patients where the time to prior WBRT is longer and extracranial disease remains controlled.

Overall symptomatic improvement after Re-WBRT is between 24 and 74% among different studies5,13,14. Measuring symptomatic improvement is problematic and can result from significant bias dependent on the measurement toll. In our study, the overall symptomatic rate was higher than previously reported, with a 75% improvement after three months. Clinical variables impact symptomatic improvement, including longer intervals between RT course, age, and performance status. Age and performance status are known factors that impact OS in patients with brain metastases and are part of the GPA assessment. Longer time between RT courses may imply less aggressive intrinsic biology of the underlying metastases, creating an opportunity for average brain recovery15.

In our study, symptoms of nausea, vomiting, and headache had the highest chance for improvement, with at least 80% improvement after RT. This may be because those symptoms relate to increasing ICP, perhaps due to pressure on the fourth ventricle. Decreasing the pressure by treating the underlying cause can result in a rapid and significant clinical response. Other symptomatic domains, including dizziness, gait ataxia, and movement disorder, are usually a result of intrinsic cerebellar injury, which is more difficult to recover from even after treatment16,17.

In our study, the measurement of symptomatic improvement was analyzed retrospectively by looking into patients’ files and physician-reported free text summaries. This method has a significant intrinsic bias18, explaining the high percentage of clinical improvement. Another measurement of cerebellum burden, including patients’ reported outcome using the 70-item Patient-Reported Outcome Measure of Ataxia, was scored on a 0–4 Likert scale. While validated and consistent, this measurement is time-consuming and difficult for metastatic oncologic patients with low-performance status19,20.

The toxicity of re-irradiation is low, as previously published5,13. In our cohort, there was only one 1 case of symptomatic RN, which is 1.7% of the cohort. Several known factors impact RN incidence. Among them is the time between RT courses (higher incidence with interval < 6 months) and the cumulative BED (higher incidence with dose > 120 Gy)21. The fact that the patient in our cohort who developed RN had received a 2nd RT course less than six months and received a BED of 126.7 Gy is consistent with previous knowledge.

Another Late radiation toxicity is cognitive decline22. Most data is related to WBRT. The hippocampi are a well-known organ that relates to radiation injury and subsequent cognitive decline with robust data on dose constraints and radiation planning to avoid high doses to this organ23. Different model showed that the mechanism of cerebellar injury after RT may be different and longer than the hippocampi injury mechanism24,25. Several studies had try to encapsulate the impact of cognitive function after Cerebellar irradiation with most of the data from the pediatric posterior fossa RT for primary tumor. Mabbott et al. in 2008 showed that pediatrics patients who had received surgery and cerebellar radiation were compared to those who had received surgery alone. No significant differences between groups for working memory and sustained attention were found, however, there was a significant difference between groups for information processing speed26.

Because most oncology patients who received the 2nd RT course have a poor prognosis with a median OS of 4–5 months, the cognitive decline after Cerebellar 2nd RT may not be as significant.

In our study we included only patients for whom a tumor board decision was favor whole cerebellar radiation and no SRS. SRS is a well-established standard for managing recurrent brain metastases due to its precision and reduced toxicity26. SRS is established for patients with 1–10 brain metastases. Retrospective Data and expert opinion are evolving for expending the indication for even more then 10 brain metastases .Today there are center for whom there is no limit number, with more focused on constrains to organ at risk like chiasm or total brain volume instead of a specific number of metastases10,27.

Nevertheless, the utility of SRS is limited by the number and spatial distribution of lesions, particularly in the cerebellum28. Due to the smaller volume of the posterior fossa, a high burden of cerebellar metastases poses a significant challenge for SRS planning. When multiple lesions are located in close proximity, achieving sufficient tumor coverage without delivering excessive doses to surrounding normal structures, such as the brainstem or the normal cerebellar neurons and the cochlea becomes difficult29. This risk is compounded by the steep dose gradients required in SRS, which can lead to unacceptably high radiation doses to adjacent normal tissue. Studies have shown that the risk of symptomatic radionecrosis increases with cumulative volume treated and higher doses to normal brain tissue, particularly when more than 10 cc of brain receives doses above 12 Gy30,31. These challenges are exacerbated in the cerebellum, where the spatial constraints further limit safe dose escalation for multiple lesions. As such, alternative approaches, including cerebellar-focused re-irradiation with or without fractionated techniques to supra-tentorial lesions, may provide a more balanced strategy for managing diffuse cerebellar disease while minimizing toxicity and lowering risk for radionecrosis and avoiding whole brain radiotherapy .

Several strengths include a relatively large cohort of unique clinical approaches. The long survival in our cohort could be explain by the fact that most patients had breast Ca origin (71%) which may represent more indolent disease for whom up to 25% can live up to 2 years since brain metastases diagnosis32. In addition 76.7% had stable systemic disease while receiving re-irradiation. In the present of evolving systemic therapy with increase evidence of controlled systemic disease33, this cohort may represent the future of patients with brain metastases.

The findings of this study hold significant implications for the management of brain metastases in the era of personalized medicine. By demonstrating the clinical benefits and low toxicity of cerebellar-only re-irradiation, particularly for patients with cerebellar-dominant disease, this approach offers a tailored alternative to more generalized strategies, such as re-WBRT. In the context of personalized medicine, these results highlight the importance of individualized treatment plans that consider factors such as lesion location and number, patient performance status, prior therapies, and systemic disease burden. Additionally, understanding the neurological symptoms and correlating them with tumor location for each patient is crucial in developing effective treatment strategies.

However, this study has several limitations that must be acknowledged. Its retrospective design introduces inherent biases, including variability in data quality and completeness. Symptom improvement was primarily based on physician-reported outcomes, which are subject to interpretation and lack the rigor of standardized patient-reported outcome measures. Addressing these limitations through prospective, controlled studies with robust symptom assessment tools will be essential to validate and refine this approach, ensuring it aligns with the evolving paradigm of personalized oncologic care. Based on the results of this study, we have initiated the preparation of a prospective trial utilizing more validated questionnaires to assess cerebellar symptoms in patients with cerebellar metastases undergoing re-irradiation.

Conclusion

Despite the relative commonality of cerebellar metastases, studies on their clinical outcomes are limited. Most of these studies combine infratentorial and supratentorial lesions into the same study cohort, masking the outcomes for patients with less known cerebellar metastases.

Our case series presents the outcomes of patients treated with cerebellar-only re-irradiation. This approach results in a high percentage of clinical symptomatic improvement with little toxicity. Age, dose deliver and time from WBRT were significant for clinical improvement. In addition, several patients were able to receive radiosurgery to supra tentorial lesions instead of re-WBRT after cerebellar-only re-RT, which may decrease toxicity. This approach needs to be validated in more extensive trials.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Gaspar, L., Scott, C., Murray, K. & Curran, W. Validation of the RTOG recursive partitioning analysis (RPA) classification for brain metastases. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 37(4), 745–775 (1997).

Sundstrom, J. T. et al. Prognosis of patients treated for intracranial metastases with whole-brain irradiation. Ann. Med. 30, 296–299 (1998).

Ma, L.-H. et al. Hypofractionated stereotactic radiotherapy with or without whole-brain radiotherapy for patients with newly diagnosed brain metastases from non-small cell lung cancer. J Neurosurg 117(Suppl), 49–56 (2012).

Patchell, R. A. et al. A randomized trial of surgery in the treatment of single metastases to the brain. N. Engl. J. Med. 322(8), 494–500 (1990).

Ono, T. et al. Re-whole brain radiotherapy may be one of the treatment choices for symptomatic brain metastases patients. Cancers (Basel) 14(21), 5293 (2022).

Sadikov, E. et al. Value of whole brain re-irradiation for brain metastases—Single centre experience. Clin. Oncol. R. Coll. Radiol. 19, 532–538 (2007).

Steinruecke, M. et al. Survival and complications following supra- and infratentorial brain metastasis resection. The SurgeonVolume 21(5), e279–e286 (2023).

Pompii, A. et al. Metastases to the cerebellum. Results and prognostic factors in a consecutive series of 44 operated patients. J. Neurooncol. 88(3), 331–337 (2008).

Stelzer, K. J. et al. Epidemiology and prognosis of brain metastases. SurgNeurol Int. 4(Suppl 4), S192–S202 (2013).

Soliman, H. et al. Stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) in the modern management of patients with brain metastases. Oncotarget 7(11), 12318–12330 (2016).

Held, T. et al. Dose-limiting organs at risk in carbon ion re-irradiation of head and neck malignancies: An individual risk-benefit tradeoff. Cancers (Basel) 11(12), 2016 (2019).

Ajinkumar, T. et al. Brain and brain stem necrosis after reirradiation for recurrent childhood primary central nervous system tumors: A PENTEC comprehensive review. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 119(2), 655–668 (2024).

Outcomes of reirradiation in the treatment of patients with multiple brain metastases of solid tumors: A retrospective analysis, Ann. Transl. Med., 3(21), (2015).

Taso, M. N. et al, Whole brain radiotherapy for the treatment of newly diagnosed multiple brain metastases. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2012(4), (2012).

Lambart, A. W. et al. Emerging biology of metastatic disease. Cell 168(4), 670–691 (2017).

Changa, A. R., Czeisler, B. M. & Lord, A. S. Management of elevated intracranial pressure: A review. CurrNeurolNeurosci Rep. 19(12), 99 (2019).

Lig, W. et al. Consensus paper: Management of degenerative cerebellar disorders. Cerebellum 13(2), 248–268 (2014).

Marcott, L. M. et al. Considerations of bias and reliability in publicly reported physician ratings. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 36(12), 3857–3858 (2021).

Schmahmann, J. D. et al. Development and validation of a patient-reported outcome measure of ataxia. MovDisor 36(10), 2367–2377 (2021).

Potashman, M. H. et al. Ataxia rating scales reflect patient experience: An examination of the relationship between clinician assessments of cerebellar ataxia and patient-reported outcomes. Cerebellum 22(6), 1257–1273 (2023).

De Pietro, R. et al. The evolving role of reirradiation in the management of recurrent brain tumors. J. Neurooncol. 164(2), 271–286 (2023).

Rüba, C. et al. Radiation-induced brain injury: Age dependency of neurocognitive dysfunction following radiotherapy. Cancers (Basel) 15(11), 2999 (2023).

Brown, P. D. et al. Hippocampal avoidance during whole-brain radiotherapy plusmemantine for patients with brain metastases: Phase III Trial NRG oncology CC001. J. ClinOncol. 38(10), 1019–1029 (2020).

Jianpeng, M. et al. Investigation of high-dose radiotherapy’s effect on brain structure aggravated cognitive impairment and deteriorated patient psychological status in brain tumor treatment. Sci. Rep. 14, 10149 (2024).

Hoche, F. et al. The cerebellar cognitive affective/Schmahmann syndrome scale. Brain 141(1), 248–270 (2018).

Mabbott, D. J. et al. Serial evaluation of academic and behavioral outcome after treatment with cranial radiation in childhood. J. Clin. Oncol. 23(10), 2256–2263. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2005.01.158 (2005).

Milano, M. T. et al. Single and multi-fraction stereotactic radiosurgery dose/volume tolerances of the brain. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 110(1), 68–86 (2020).

Minniti, G. et al. Neurological outcome and memory performance in patients with 10 or more brain metastases treated with frameless linear accelerator (linac)-based stereotactic radiosurgery. J. Neurooncol. 148, 47–55 (2020).

La-Rosa, A. et al. Dosimetric impact of lesion number, size, and volume on mean brain dose with stereotactic radiosurgery for multiple brain metastases. Cancers (Basel) 15(3), 780 (2023).

Rangwala, S. D. et al. Stereotactic radiosurgery for fourth ventricle brain metastases: Tumor control outcomes and the need for CSF diversion. Patient series. J. Neurosurg. Case Lessons 8(22), CASE24293 (2024).

Grimm, J. et al. High dose per fraction, hypofractionated treatment effects in the clinic (HyTEC): An overview. IJROBP 110(1), 1–10 (2021).

Leone, J. P. et al. Breast cancer brain metastases: The last frontier. Exp. Hematol. Oncol. 4, 33 (2015).

Alhalabi, O. et al. Outcomes of changing systemic therapy in patients with relapsed breast cancer and 1 to 3 brain metastases. Npj Breast Cancer 7, 28 (2021).

Acknowledgements

I wish to acknowledge the contribution of all the neuro-oncological and Radiation oncology Department at Sheba medical center.

Funding

The experimental data and the simulation results that support the findings of this study are available. No external funding was used.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

OH -DATA analysis, statistical analysis, prepared figures and wrote main manuscrip MJ-english editing and scientific review YL-scintific review and radiation data AT-scientific review and neurological data.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

All experiments were approved by the Institutional Review Board ofSheba Medical Center and all methods were performed inaccordance with the Declaration of Helsink.

Informed consent

Patients treated in this cohort have had informed consent to the useof radiation planning and medical chard for research properties

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Haisraely, O., Jaffe, M., Lawerence, Y.R. et al. Cerebellar re-irradiation after whole brain radiotherapy significant symptom relief with minimal toxicity in metastatic brain patients. Sci Rep 15, 4078 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88652-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88652-7

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Synergy of radiotherapy, focused ultrasound, and immunotherapy in the treatment of brain metastases

Journal of Neuro-Oncology (2026)